50 minute read

A Conversation with Jackson Browne

A CONVERSATION WITH

Jackson Browne

Advertisement

By Brennen Matthews Opening Image by Nels Israelson

Iam often asked who is on my celebrity bucket list to interview. I generally answer in the same way each time; I don’t have a wish list of people to interview, but I do have a select shortlist of folks that I would love to have a real conversation with. I have a deep passion for fascinating conversations with diverse, creative people. I love discovering more about film, TV, and music talent whose work has influenced me and the chapters of my life. I am drawn to artists who have a long and remarkable backstory. My list is short, but at the very top is a singer-songwriter / musician with era-shaping music that has left an indelible imprint on many lives. His lyrics and sound speak soulfully to the emotional ups and downs of life. He has inspired countless artists and won the admiration of many of his peers; people who define classic rock and lyrical prowess. In 2002, he received the coveted John Steinbeck Award, in 2004 was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame by none other than Bruce Springsteen, in 2007 he was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame, and in 2014, he won the Spirit of Americana Award. He has thrown his energy behind important causes that help to make our planet a better place. When I am asked who I would be fascinated to sit down with, I always answer the same way: Jackson Browne.

In the early days of your musical journey, you found your way over to the iconic Troubadour. How did you end up playing there? Were you invited to perform?

No, you wouldn’t be invited, you would just go and sign up. The Troubadour was interesting. To me, it was not an iconic place. The Ash Grove was iconic. The Ash Grove was where the traditional musicians played, where the Georgia Sea Island Singers or the Chambers Brothers would play. I mean, it was a traditional club, and I’d been there with my dad. My dad took me there when I was about 14 to see Lightnin’ Hopkins. When I was in high school, I started singing in this club called the Paradox in Orange County with my good friends Steve Noonan and Greg Copeland — who were really my sister’s friends — and I kind of tagged along. I was 15 and they were 17. They were seniors in high school, and I was a sophomore. They let me hang with them and listened to my songs and taught me stuff. They were so cool to me. Greg Copeland wound up going to San Francisco State. None of us had a car and we would hitchhike up the coast to visit him and spend the night on his floor and go wandering around North Beach. I mean, this is pre-Haight-Ashbury. It was 1965. I hear people talk about the Summer of Love as 1967 but to me, it was ‘65.

So, I started singing and hanging around these clubs in Orange County. And then I heard about the Troubadour Hoot, from Jim Fielder, who was the bass player for Tim Buckley, who would play these clubs that I was hanging around in, and we became friends. We would play the open mic night at the Paradox and then go to my house afterward. My parents were so cool, they let us just hang and there’d be a room full of kids with guitars. I grew up listening to blues and collecting blues records. But Fielder told me about the Troubadour Hoot and said, “You just go there, sign up, and wait your turn. You can sing up to four songs.”

Usually, at the Troubadour, it was a procession of people going up to the mic and singing either folk ballads, their own songs, or songs that other people had written. Yeah! It was the big city.

Had you written “These Days” by then?

Maybe, maybe not, I don’t remember. The cool thing is that my friends played my songs. I didn’t sing very well. They would sing my songs, but it was an odd thing for me to try to do, because I wasn’t that comfortable on stage, but it was fun. I started doing it fairly regularly. It was on Monday night. When I moved to LA, it was easy to get there every Monday night. I hung around there for about a year, but I didn’t have a house in Los Angeles, I stayed in Laurel Canyon at my manager’s house—Billy James.

I became a regular at the Troubadour on Mondays, and eventually, the guy that ran the signups said, “You don’t have to get here at four o’clock and sign up.” However, I liked going there at four o’clock in the afternoon because everybody that was trying to get on stage was sitting around singing. There was a little alcove, where the ticket window was. It was a little huddled group of people... and then you might catch them playing that night or you might be in the bar when they’re playing. And if somebody was really good, everybody in the bar would pour into the club and listen to them. I remember when they started the bar, because that was a big change from the coffee house; to have drinking was a whole different thing. I wasn’t old enough to drink, but I noticed that it became a whole different clientele. You’d look over and see Al Kooper (Blood, Sweat & Tears) talking with Odetta, two New York people, and it’s like, ‘Wow, that’s Odetta, and that’s Al Kooper!’ People were too cool to go up and say, “Oh man Al, can I meet you?” People don’t do that. When I think about it sometimes, I think, ‘Man, why didn’t you tell him how much his music meant to you? You were just too f*cking cool to say that. Why did you not say, “Dude I’ve listened to your records from...” ’

David Crosby came into your journey pretty early on. How did you guys connect?

I met Crosby when he came by the house I was living in with a few other musicians — on Ridpath Drive. What happened in Laurel Canyon in those days was that everybody went to each other’s houses and they sang songs for each other, and Crosby would come by, and he’d say sh*t like, “You guys are lucky man, no one knows who you are, you got a clean slate, the future is yours.” He was very, very generous, and a very charming guy. Not that he’s a humble person, he would say humble sh*t like, “I don’t know what I’m gonna do next,” and he’d been in the Byrds! It was right before they [formed] Crosby, Stills & Nash.

Crosby would come to play with this friend of mine named Jack Wilce. And Jack was sort of in our band. We weren’t really a band, we were sort of a collective of people who were trying to get Elektra Records to let us make a record, and everybody was playing each other’s songs. So, Crosby would come by. Paul Rothschild lived across the street from my manager. He was the Elektra Records producer that produced the Butterfield Blues Band. He was very friendly and attentive, and he’d say, “Hey, have you ever listened to Bertolt Brecht or Kurt Weill? Check this out.”

The thing that’s notable about Laurel Canyon is that producers and artists and record company executives, were all sitting around together and getting high, listening to music, and listening to each other, and it was no longer a hierarchical thing. You met people on the street corner, you met them standing in front of the Troubadour, you met them in the Troubadour bar. Now, the Troubadour has been lionized as this meeting place where everybody hung around, and it’s true, especially on Monday nights, but the rest of the time they were in each other’s houses, and they were in studios together.

It wasn’t a dog-eat-dog rat race, trying to get signed, where you were competing with other bands. There was a whole egalitarian culture of musicians interested in each other’s songs.

Did you find that the people who found success first were very welcoming to newcomers on the scene, or was it more cliquish by that point?

I don’t think it was cliquish at all. I think that there might have been some... I just read something last night about that. I think Graham Nash said that in England it was cliquish, that there were these hierarchical levels; there were the Beatles and below that the Stones and then the Who, and so on. But I don’t think that it was that way in Los Angeles. But because I was immersed in it, I don’t think that I knew then how to compare it with anything else.

Were you at Woodstock?

No, Woodstock happened, and I heard about it like the next week. It didn’t happen on the West Coast, and if you lived on the West Coast, you didn’t hear about it until later.

Interesting.

Did you think Woodstock was a national event?

Not national, but a lot of West Coast bands headed over to play Woodstock, I guess I assumed that people would have heard.

I’m sure you heard about it if you were a band like CSN. I did go to Monterey though, in a VW van full of my friends.

That must have been a great concert.

Yeah, that was incredible. Monterey was like the first time anything like that happened. Woodstock was the next time, and they were only a couple of years apart. And then they started having festivals all the time.

How did you and Glenn Frey meet?

Glenn and JD [John David Souther] and I met at a benefit. We were gonna sing on the radio... A DJ that I knew from a producer friend’s swimming pool told me, “We’re doing a show for the free-clinic, you should come by and sing.” But when I got there, he was gone. I stayed around for hours waiting to sing on the radio, but the people there didn’t know who I was. And in truth, I wasn’t anybody. “So, why should we put you on the radio? Are you going to make people call in and donate?” And JD and Glenn were there, in the same situation. That’s where we met, and we just hung around there for the afternoon. And then they showed up at a club I was playing. I told Glenn that my sister’s apartment was going to be vacant and to check it out. That was next door to where I was living. He moved in there, and a few months later, I moved into the sort of basement below him. We all hung in the same clubs and we bumped into each other all the time. Then JD moved in with Glenn. They were living upstairs, and I met Jack Tempchin through them. It was like being in college, except you’re not really going to school, you’re just doing what young people that age, 18 or 22 do. And they also played the Troubadour Hoots.

Your career took a very important turn when you got on the radar of David Geffen. How did that happen?

Crosby had told me about him and at some point, I sent him a letter. Crosby said that he was going to tell him about me, but he didn’t. He just got busy. That’s not his fault, he got back in the rock star business and he was busy. But I remember going to watch Crosby, Stills & Nash play the Greek Theatre, and waiting around at the stage door until Crosby finally came out with all his beautiful friends. I’m sort of standing there with all the other people who had seen the show, and he said, “Oh hey, how are you doing?” (Laughs) And he just blew past me.

But I finally went in and met Geffen, and he agreed to manage me. I’d been hanging around for a few years by then and it was like, ‘Wow, great, something’s gonna happen,’ and then I didn’t really do much for another couple of years because Geffen said, “We’ll take it easy, you’re still learning to sing, and this is going to be great.” He did try to place me with a couple of record companies, and they didn’t really go for it. Meanwhile, he was thinking about starting a record company. And there are some funny accounts of all of this, like him telling Ahmet [Ertegun - co-founder and president of Atlantic Records] “You sure that you don’t want to sign him? He might make you a lot of money,” and Ahmet saying, “Why don’t you sign him David and then we’ll both have a lot of money?” (Laughs)

Initially, didn’t Geffen throw your demo tape and letter away and his secretary later fished it out of the trash?

Yeah, her name was Noni. She was terrific. She said, “David, you might want to listen to this, I think it’s kind of good.” And that demo was JD Souther playing the drums and Glenn Frey playing the bass and me singing the song “Jamaica”, and them doing some harmonies on it. JD and Glenn of course sang really well... it wasn’t really a great record or anything, it was just a demo made in the studio of my publishing company. I didn’t know he’d thrown the thing away. You get told that kind of stuff later and then it’s a story. Once I was gonna make a record, Crosby was absolutely available to sing on my record. He did sing on it, and that pretty much put me on the map.

David Crosby called you incredible and “one of the probably ten best songwriters around [with] songs that’ll make your hair stand on end”. As a young songwriter, did you feel much pressure to keep churning out the next great song?

I had a friend named Michael Vosse [A&M Records publicist]. And Michael was a good friend of my friend Pamela Polland of this band called The Gentle Soul, and I hung out at their band’s house a lot. Besides my manager’s house, that was like my second home. Man, I didn’t have an apartment. I didn’t live anywhere, really. Eventually, my mother moved to Silver Lake, so I could stay there. At that point, home was no longer Orange County.

Anyway, Michael Vosse worked at A&M Records, and I was so lucky to have that kind of mentoring from people. My manager was a guy named Billy James who had worked for Columbia, and who also opened the West Coast office for Elektra Records. Like I said, Hollywood was a place where you actually met people and got to know them. I was lucky. Michael listened to my music and said, “Some of these songs are pretty good, but what you’ve done is, you’ve written the same song over and over again.” He put that in my head, and from then on I thought, “Okay, I have to make each of these songs distinct. I just gotta go a little bit further and make each of my songs the only one that is like “that” song.

Then Michael got me a meeting with a publisher named Chuck Kaye at A&M. And this is more like what usually happens in those meetings. He said, “Oh, okay, well,” (after I had played about six or seven songs) “That’s good, I like this one here, you should go write some more like that one.” I had played him “Rock Me on the Water” and he said, “Okay, go write a bunch more of those.” It was then I had the realization that record companies don’t always know what they’re doing.

You spent four months recording your first album, and in the middle decided to take a road trip. It was around this time that you had your infamous breakdown in Winslow, Arizona.

I wanted to visit the Hopi Reservation in northern Arizona where I had been as a kid.

I was driving a ‘53 Willys Jeep wagon. It was a great old car, but it wasn’t a very strong or powerful car. It didn’t even have a radio. What I had for a sound system in the car was a tape cassette player that was about the size of two loaves of Wonder Bread. It was huge and it had a speaker in it that sounded great to me. I had a Creedence Clearwater Revival album that I bought with the cassette player at a pawnshop, and I had a Santana record.

It was great to be out on the road. It was great to go back to the Hopi Reservation. At one point, I was really tired and pulled over to the side of the road, this is somewhere in Arizona around Tuba City, and I decided to sleep for a while next to the car. And somehow, I wasn’t in the sun when I started to sleep, but eventually, the sun came around and I just roasted myself. I was just burnt on one side like a hot dog. I went and found a motel and just turned up the air conditioning and laid there for a day.

The Jeep finally broke down in Winslow, so I wound up spending some time there trying to learn how to rebuild a generator and walking back and forth between my stalled car and the parts store where they were sort of giving me a tutorial on how to rebuild this thing. There were coils and brushes and things that had to be replaced, and these guys in the parts store just kept giving me pointers over the counter. So, I walked back and forth to my car until I got it running again. I really don’t remember. I might have been sleeping in my car all the way. No, I must have been, because I remember the motel with the air conditioning being a big expenditure. I didn’t have any money. But I never had any money, so it wasn’t that big of a deal. I guess I had enough, probably had a couple of hundred bucks.

How many nights do you think you actually stayed in Winslow that time?

I had to have been there a couple days, but I don’t remember. I don’t even have a picture in my mind. The picture I’ve got in my mind is of this campground outside of Flagstaff. But I met this Indian guy in Winslow, and he took me, I mean, I drove, so either after I got my car fixed or before it died, we drove to this creek, it literally had boats in it. Winslow’s got like, a little marina. Crazy, right?

Did you know that you were on Route 66 when you were traveling?

I probably did, but it wasn’t that big a deal to me. There was a television show called Route 66. So, I might have pondered that a little bit, I don’t know, but it wasn’t as much of an iconic highway, in my mind at the time. I mean, it was also a song, “(Get Your Kicks On) Route 66.” It’s all pretty far back there.

Have you driven all of 66, from Chicago to LA?

I’ve never done it in one piece. I probably have in my years of touring, I’m sure I’ve been on all the highways that make up Route 66. I did a lot of antique stores, but funky ones. I don’t mean like, looking at restored furniture, I mean, stores where there’s a few rattlesnake skins up there, maybe a coffee can with human teeth in it. Funky stuff in there. As a matter of fact, I even bought some of those teeth. I don’t know whose teeth they were. (Laughs) And tried to make a necklace out of them. Have you ever noticed that people in the desert line their property with bottles? I loved all this stuff. And the size of the sky. I don’t remember seeing anything that said, “Historic Route 66”. In those days, it hadn’t been restored or exhumed.

You’ve stayed at the La Posada, right?

Yeah, I’ve stayed there a couple of times. It’s a beautiful, historic hotel. A friend of mine named Doug Aitkin, who’s a conceptual artist, invited me to take part in an art happening. It was a conceptual art piece that had to do with America’s train system, and because La Posada was where the train station was, that was one of the stops. It was called Station to Station and it went from New York to Oakland. And he had a train, and they created art installations along the way, in various towns, and there were certain people on the train doing things. Cat Power [singer-songwriter] was on the train, Giorgio Moroder [Italian composer/songwriter] was on the train. Just the combination of Cat Power and Giorgio Moroder would have been interesting, but I couldn’t see getting on the train, because I didn’t think I’d be able

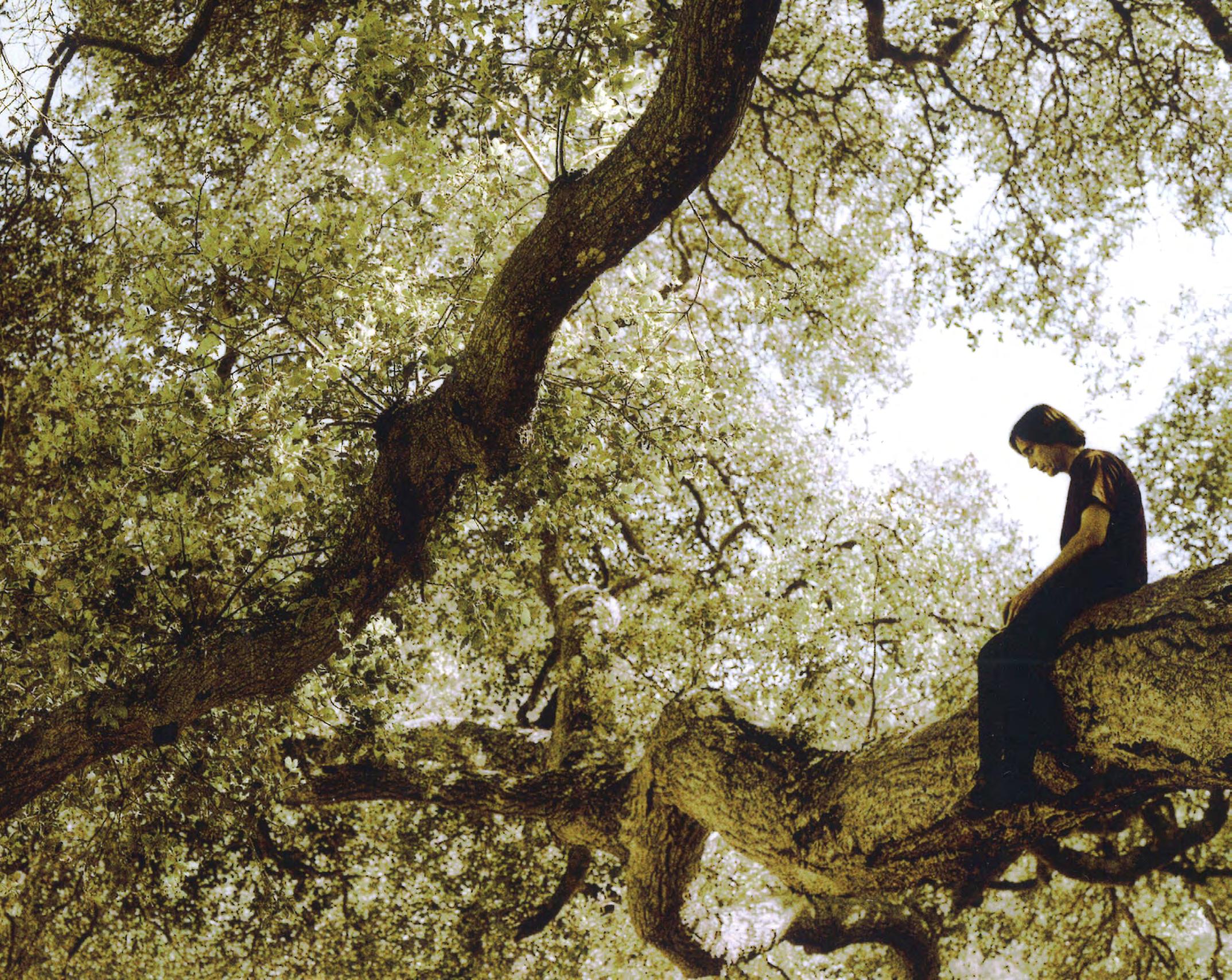

Image by Nels Israelson. 2002.

to get enough of my instruments on. So, I decided to do a show at one of the stops. We did this show at La Posada in Winslow, and it was incredible. They had taken aboard the train these two sisters who did flamenco, they were from somewhere in New Mexico, and they were really great, really cool flamenco dancers. Cat Power did a show in Winslow and I did a show there. Mavis Staples [American rhythm and blues and gospel singer] had done a show in Chicago. Various people did shows in different places, and I chose Winslow, for obvious reasons, I just thought this would be celebratory and it’d be like a return to Winslow and a chance to play there. I wrote a song for it called “Leaving Winslow.” Beck did a show in Barstow, California, which makes Beck one of the coolest people I can think of. He chose Barstow!

Out of your broke down in Winslow experience came one of the most famous songs in the world, “Take It Easy”. How far did you get with the song before Glenn Frey got involved?

I had the song about half written, up to “Standing on the corner in Winslow, Arizona,” and that’s as far as I got. Although I think I had the last verse too. The Eagles were about to make their first album, and they had been playing this bar in Aspen, to get the kinks out and to develop musically, and I gotta say, when they put it together, it really worked. They went into the woodshed and spent time singing and getting it right, and what they had was that amazing vocal sound. They had made this trip to Aspen by car, and when Glenn heard that line he said, “Winslow. I know Winslow.” I was seeing an Indian man standing on the corner. In my mind, I was saying, “standing on the corner in Winslow, Arizona,” and wondering how to somehow sum up my experience. That’s the inspiration for that line about standing on the corner. But Glenn put himself on the corner: “I’m standing on the corner,” and he had this girl slowing down to look at him, which is kind of classic Glenn Frey, you know?

Did you write the chorus or is that something that Glenn also wrote?

I wrote the chorus, and I had a version of that last verse. Glenn really wrote a very small part of the song, but I hasten to say, it’s the part everybody remembers the most. He got so much in that one line, you know? He got “Lord,” “Ford,” “girl,” and “bed” into the same line.

How did he even get involved in working with you on the song?

He came to visit me at a studio that I was working at called Crystal Sound, which was in the same part of town as a restaurant that we all liked a lot. We decided to walk to Lucy’s El Adobe, and as we walked, I sang him that song, walking to lunch, and he said, “Are you gonna do it for your

record?” I said, “No, I don’t think so, because I’m finishing the record now.” This is after we had resumed making the record. I’d spent three weeks in the desert, and I came back and we were putting it together. I actually started the song in the back of a Dodge van, because my Willys Jeep broke down for good, after having gotten me as far as Zion, up in Utah.

I was coming back... and this is really amazing luck. I had met these two guys who were just out of the military. They had been MPs in Vietnam. This guy, Buckmaster was his last name, and he was such a charismatic guy. He and his partner had put together these communal feasts up in the campground in Zion. He was a guy that just walked up to people and met them; he was so personable. They were driving this grey Dodge panel van. We had partied together in Mount Zion National Park. Then I left.

But there I was on the side of the road, broken down, and they knew my car, so they stopped and picked me up, and drove me back to LA. I left the car there.

You just abandoned it?

Well, I didn’t abandon it. I think that we might have towed it to a gas station. I didn’t just abandon it because it was worth a few hundred dollars. And I thought, “I’m gonna have to come back out here.” I just went out there and sold it. I don’t really have much memory of that, but I think I remember having to take a Greyhound bus to somewhere out in the middle of the desert.

Anyway, I had done that once before on a trip with friends from LA to San Francisco. My family’s car broke down in Santa Maria. And it’s funny how you remember the names of these people who come to your rescue, but a man named Belden Dockstader bought my family’s VW van from me for the price of some Greyhound tickets out of there. (Laughs) My mom was like, “What happened to the car?” “Well, it died.”

But meanwhile, Glenn and I were walking down this alley and I already had half the song, because I had started writing it in the back of this panel van. In fact, the melody of “Take It Easy” is a little bit of a recycling of a melody of a song that I had that never really was a whole finished song. And so, it just sort of came at that time.

I gotta say this, in those days, our songs weren’t hit songs. I was just writing a song, and it wasn’t finished, and Glenn said, “I like that... we could do that.” I said, “Oh yeah, you should.” And he said, “Well, when you get it done, tell us, and we’ll do it.” I said, “Great.” And then he wanted to know if I had it done yet. He called me several times, wanting to know if it was done, and it wasn’t. He said, “Do you want me to finish it?” And the first time he asked that I was like, “No, I don’t want you to finish it! I’ll finish it.” But the next time he asked, I thought, “Yeah, absolutely, you want to finish it? That’d be great.”

And when he came back with that line, I just thought, “Wow, that works, that really works, that’s great!” Because it made that song, and not only that, the Eagles arrangement of it made it. If I played it for you the way I had it... what Glenn heard was what he was going to do to it. Until they sang it, it didn’t have that big sweeping chorus.

In the early days, The Eagles did a lot of covers, they sang a lot of songs by other people, but they have this incredible arrangement sense, and that was Glenn’s strength. More than writing, he was arranging. In the band, they called him

Did you attend the ceremony when Winslow opened the ‘Standin’ on the Corner’ spot?

I did not. They wrote me a letter and told me that they wanted to make a statue and I talked with them about it. I said, “Look, you should make it of an Indian, you should make it of a straight-backed Indian with a cowboy hat, boots...” They told me that they were not going to make it look like anyone in particular, but a lot of people assume that the statue is me. So much so that, they added another statue that is supposed to be Glenn, but it doesn’t look like him either. (Laughs)

The funny thing is, as soon as people started hearing that song, they said, “Winslow, I’ve been there. I’ve been to Winslow.” Before that, I had never heard of it. But you’re out there in the middle of the desert and suddenly you come upon this town and it’s Winslow. At the time, I mean, now I’ve been there many times, coming and going to visit my family in New Mexico, and spent the night a few times at La Posada. And it’s a bigger town than I remember it being. I don’t know if it got bigger since 1972, but back then it seemed to me like it was only about six blocks long and two blocks wide.

You live near the Santa Monica pier, which is the official end of Route 66. Do you go down there very often?

The pier? Yeah, now and then. It’s funny, you can get to the beach more often when you live inland than when you live right here, because you got business to take care of. I was down there the other day, but I don’t go there every day. The great thing about Santa Monica and the beach is that the people at the beach, they’re on their way somewhere good, they’re just hanging, they’re relaxing. I took photographs underneath that pier for my new record. It’s nice under there. Under the boardwalk, people just hang there in the shade underneath the pier. It’s great because the water comes right up, these pilings and pylons.

Are there any songs in particular that you’re most proud of?

Oh, of mine? Sure, I have songs that I think are my best songs.

It’s funny, because I was just singing a song last night and thinking, ‘This is one of my best songs.’ It’s not the most well-known song. The song is called “Yeah Yeah.” That is a terrible title, I know, but it’s all I could think of. But the song itself really took me. I wrote it over such a long period of time. I started that song probably in 1980-something. I wasn’t trying to write it the whole time, obviously, you forget about it for years at a time, but I had the first lines. I could never figure it out. I just couldn’t. But when I finally cracked the code... and, actually, I had to make a fundamental change in the first line, and then, bang, the whole song happened.

Here’s the thing, you have a song like “Standing in the Breach” (2014) ... a lot of my songs are fraught with endeavor, they’re trying pretty hard. (Laughs) And then the songs that sometimes are the best are the ones that just happened quickly. I remember thinking that, like on my

second album, there’s a song, “Sing My Songs to Me” and it segues into “For Everyman.” Now, “For Everyman” was a song I spent a long time writing and trying to make a point. But “Sing My Songs to Me” was something that I wrote, probably a long time before that. It was a carryover from before I had a record deal. It’s curious in that it’s a song sort of looking back nostalgically. This is something I wrote when I was about 16, looking back nostalgically at what? How much had I lived by then? Nonetheless, there’s something in it that I think is really good and something that I didn’t try to do. I didn’t try to do anything, and this good thing happened, and then when I went and recorded it, it wasn’t the most important song on the record, but we found a cool way to do it. I guess what I’m trying to say is that sometimes, the songs that you work long and hard on, that you invest in and give the most importance in your mind, may not be your best song at all.

You wrote “These Days” when you were 16. You’ve said that at the time you didn’t think that it was a terribly deep song, but those lyrics are highly nostalgic and reflective. Quite poignant for adults, let alone coming from a 16-yearold. What’s the story behind “These Days”?

Well, most songs come about with a little piece of music. I think I’d been out walking... I don’t think you really start writing songs from the part of it in which you’re trying to say something important. I think you start by trying to describe something that you recognize, and sometimes it’s the whole kernel of the idea, but in “These Days,” what’s in there is a kind of regret. I don’t really know where it comes from, but there’s a kind of wish to do better. A wish to somehow overcome. Take stock. A kind of sorrow. I can tell you that at that time in my life, I think I did have some stuff to feel nostalgic about.

For instance, I grew up in Highland Park in this beautiful home that was my grandfather’s [Clyde Browne] creation. He named it the Abbey San Encino. He built it out of river rock and blue granite that he got from various demolition sites, and he just built this thing. To me, that was like, you look at this house and it was unlike any other place, and people came all the time asking, “What is this? Is this a church? What is this place?” And you’d say, “Well, this is a private home.” There was no fence around it, and it was too easy then; they’d walk right into your house. Right through the front door and into the patio. (Laughs) But we moved to Orange County when I was 12.

At 13 or 14, my parent’s marriage had broken up. We were all living with my mom. After a while, my brother went to go live with my dad. So, even though it seems like 16 is a young age to be writing a song about your own feelings of failure or the things that you remember as having been better, I think that occurs in every life and often it does happen early.

Do you ever look back upon that time and just think, ‘Wow, there was a lot going on in my life and heart to write “These Days”?’

Yeah, I do. I think about it from time to time. I’ve actually been thinking about it a lot recently because of the Ron Brownstein book that I showed you that is coming out. It really put me in mind of a lot of this stuff, like, how did I get here? It’s somebody talking about the year 1974 and what goes into that period of time; ‘74 is a lot closer to ‘68 than it is to 2021.

I think I’m still sad about my parents. But your parents break up and you deal with it. I’m sad about my sisters, both my sisters are deceased now. They had a really rough time, both of them. There’s a lot of fallout from their lives as a family. I know some really wonderful families that are so... the mom and dad are solid and they’re functional, and the kids are doing so well. And I see what goes into it. And my own family had pretty little of that, although my mother was terrific. My mother was really great, but I just don’t know what it would have been like if we had had that kind of family life.

Even now, I see my son, Ryan, who’s got a two-year-old. He is such a terrific parent. And at times when I’m with them, I reflect on my own parenting, and it makes me kind of blue. I think I could have been a much better parent. But to see somebody who does an incredible job and go, “Oh my gosh, I see what you’re doing and it’s just so attentive and focused,” and he didn’t learn it from me, he got it from his mom.

I’m from a family where the marriage didn’t stay together, and I’ve been in a relationship for a long time with someone who is also from a family that the relationship didn’t stay together. You’re still a family. Everybody is still your relative, but it’s just not the same. But also, I feel that there are tragedies in our lives where we just move on and just keep going and trying.

Image by Bill Carter. September 2020.

Image by Dylan Coulter. 2021.

With Phyllis’ passing in 1976, you went through a major tragedy yourself. Ethan was about two years old at the time. What was it like being a single dad, raising a son, and being a musician, and pursuing your career? I mean, so much going on. What a balance to try to maintain.

Well, it was my main focus. I only had two things that I hoped I could fit together: being a songwriter and a father. And I looked at it like this, if I have to only be a father, I hope I’ll know it, and just do that. But life’s not like that and you don’t get a notice in the mail saying you’re blowing it as a parent. You think you have the advice and the help you need, and sometimes you don’t, or you don’t heed it. The mistakes I’ve made as a parent are still with me. I think about them fairly often. It’s not that you’re not trying the whole time. It’s not that I wasn’t trying then. You’re just distracted by other things and some things don’t occur to you. Or maybe you ignore advice that you should have taken, because you’re overconfident.

On the music part of it, it seemed to me like I had every advantage. I was making a good living and I could hire people to help. So, you think that you’re doing it, that it’s covering it. That may not be the answer at all, or the person that you hired may not be the right person; the person that you hired to spend time with your kid while you’re working. But it’s not for not caring. It’s just from not having enough experience, and not having enough consciousness to spread between the two different areas of your life.

Like for instance, my mother was a teacher and her students adored her, and they have come up to me ever since she was a teacher saying, “Your mother’s the greatest teacher, she made the biggest difference in my life.” And I know what they mean, because she did that for me. She encouraged me. I know how to do that, but there’s a lot more to it. The main things are interest and involvement. But when I look at my son, he’s interacting with his son, like, all the time! It’s like, “Wow.” So, it’s the idea of being absent for big pieces of time, and still thinking that I’m doing it, I’m showing up, I’m there every day, or I take him everywhere I go. But...

Another interesting thing I came upon recently when I thought about the song “For a Dancer,” which I wrote about a friend of mine who died in a fire... He was the brother of a really good friend of mine, somebody that I was close to, and he was an outlier, like a person connected to our scene, but he didn’t make music himself. But he was very creative. I wrote “For a Dancer” because when he died, that was the only way I could process it. And I wrote that living in the Abbey with Phyllis and Ethan. And then it wasn’t until many years after that I realized that the song had traversed in my life and had become about her.

I’ve sung that song for so many people whose family members have died. People recognize their own loss in that, and so, what I realize is that the songs may originate with me talking about my life, but by the time they’re a song, they’re actually about other people’s lives. And you hope that there’s something universal in them. And this is one of the wonderful mysteries; how you can put in particular details that are only from your own experience, and that gives us even more exactitude. It gives it more of a particular reality — even though those details are your own details — that make it even more universal. And some of the songs, you hear more in them the longer you sing them. You accumulate more experience and more memories and suddenly, certain lines resonate even more now than they did before.

I’m someone who believes that there’s a lot to be said for melancholy. I think that some of the most introspective times in life, and some of the best ways to get through difficulties come when you allow yourself to be sad and to process it. “Fountain of Sorrow” very much speaks of this in my mind.

The lines:

Looking through some photographs I found inside a drawer I was taken by a photograph of you There were one or two I know that you would have liked a little more But they didn’t show your spirit quite as true You were turning ‘round to see who was behind you And I took your childish laughter by surprise And at the moment that my camera happened to find you There was just a trace of sorrow in your eyes

It’s been rumored for a long time that the song was inspired by Joni Mitchell. What’s the real story?

was going on in the song was, you’re looking back at someone you knew, and you realize that there were things about them that were there the whole time that you didn’t really pay attention to in the moment. To me, the title should perhaps not be “Fountain of Sorrow,” but “Fountain of Sorrow, Fountain of Light.” It’s about that very thing you just said, you know, it’s where you get the information from, it’s from your sorrow. It informs you. It’s like what we were saying about “These Days” too, your regret is somehow your teacher. What you would do differently if you could. What you wish you’d known that you didn’t. But, in “Fountain of Sorrow” ... I can still see this photograph that it was based on, really it was a photograph that I had taken of her. And she was sneaking up on somebody, and she was taking pictures... She’s the one who got me into cameras, and so she was gonna take a picture, and she was cracking up. But the fact that I said ‘there was just a trace of sorrow in her eyes’ ... in this particular photograph, I don’t think that’s true, but I put that there because from that vantage point after a relationship, you see that there’s a sorrow. I know it’s there, now, but I didn’t know it in the moment. And it’s not really in that photograph. So, I kind of commandeered the idea of looking at a photograph to just say this thing.

Writing is a mysterious process; you just say stuff and you don’t know why you say it. You know what you’re trying to get at, and finally, by the end of the song, you might have filled in enough of the picture that you get the truth of the situation. I think I err on the side of making sense. But it’s for a purpose, like I really go about getting in touch with the underlying story, the underlying truth, even if it’s a fable. The idea that you paint a picture and you get something from it, telling that story. It’s based on something true. There are times that you can’t finish a song because you’re not really clear on what the truth is.

With the song, “Jamaica,” I thought that I was writing it for this girl that I met, who worked in an organic vegetable orchard in Malibu, actually right by where Shangri-La Studios is now, like right out by Zuma Beach. And it was an idyllic little song, but what the song really describes is the relationship I had just been in, in which I had wanted to hide. I was content to just be with this girl. And she was ready to move out into the world, and she was so vibrant. She was such a knockout and she was constantly being invited places or approached or hit on, in all those ways in which a beautiful young woman in full sail is. And I, in no way, was a match for that. I wasn’t doing that in my own life, I was hiding in her. And so, that’s what “Jamaica” is talking about. That’s really what happens when you write a song, sometimes you don’t know what it really is that you are talking about, and that’s okay.

“Somebody’s Baby” provided you with a big hit single in 1982. That track was a little different than some of your earlier work.

It’s funny about “Somebody’s Baby” because that song is connected to a movie [Fast Times at Ridgemont High]. People have imagery of like, the cabana scene. Or they have their own thing that they did that year or that summer. I had a friend who was an activist who literally complained to me, “You’re saying in this song that she’s not really anybody unless she becomes somebody’s girlfriend.” I’m going, “No, no, no, I don’t mean it like that. I mean that she wants to belong to somebody.” And I had this whole conversation about it, but I really didn’t think that I was saying that much in the song. A therapist that I used to see said, “Look, I think you’re wrong about this song,” because I was really hard on the song. He said, “I think that the song is about something really important. It’s that everybody wants to belong to somebody, wants to be wanted, and the idea that you see somebody, and you think that they must be taken,” and that whole idea. He said, “It’s about something really so simple and so valid that it doesn’t even come on your screen.”

Now in my shows, I go to sing that song, and it’s a moment. I see an entire audience full of women get up and dance, and some of them are young and some of them are old, and some of them are skinny and some of them are plump, and they’re all beautiful. They all feel beautiful. And I think to myself, “Wow, this song makes them feel beautiful. They feel like who they are is just right. And they’re smiling.” It’s a gift to me.

By the way, as collaborations go, I didn’t start this song, and it was a hard song to write, it was really hard, because Danny Kortchmar [guitarist/songwriter/producer] had this really great hook, and he had this one line, “She’s got to be somebody’s baby.” I thought, “It’s gonna be hard.” So, I’m maybe the most proud of having come up with the rest of that song, because it didn’t start out as my idea.

What do you want your legacy to be, Jackson?

I think it’s in the songs. When you talk about legacy, that means what other people can see of you or what other people will remember of you. And that’s what other people will get, the songs. But the actual relationships, the time spent with friends, the discoveries you make about life, and about places in the world that you’ve visited — all that stuff is pretty much between those people that did it. I am losing a lot of friends. I have two friends that just went into hospice yesterday. I lost one of my very best friends six months ago. I’m really looking at how much of a person’s life and times is sort of in the things that they collect. I just listened to a talk last night by Eckhart Tolle [spiritual teacher and best-selling author] saying, “It’s not the things. If you imagined your life to be a room,” he says, “It’s not the things that are in the room. Your life is the space. And in that space of a life, a lot of people pass through and a lot of places are visited, and things happen.”

Unless I wrote a memoir, and I think about that sometimes... but I almost feel like I’d have to stop living my life to recount it. And maybe the people I know who have done that are just better at carving out the time to sit down and write. But I’m also trying to write a few songs. When I ask myself what I want to do in my remaining years, I’d like to write some more songs.

Be sure to check out Jackson’s new studio album, Downhill from Everywhere, to be released this summer. It offers some fantastic tracks that are undeniably vintage Jackson Browne, and a few contemporary tunes.

GILLIOZ THEATRE

Beginning in 1926, tourists traveling on Route 66 were met with an explosion of one-of-a-kind diversions and attractions designed to give passersthrough a sense of each of the enchanting little communities that give the Mother Road its magical reputation. It was amid this boom of movie houses and concert halls, in Springfield, Missouri, the birthplace of Route 66, that M.E. Gillioz’s eponymous theatre came to be.

“Gillioz desperately wanted to be on Route 66,” said Executive Director of the Theatre, Geoff Steele. “If you look at the announcement of Route 66 and took a map of [the road] and put lights everywhere a theatre opened between 1926 and 1935, it would look like a string of Christmas lights. It just really captured the imagination.”

Bridge architect Maurice Earnest “M.E.” Gillioz of Monett, Missouri, was one of many people struck by the ingenious aura cast by Route 66. By 1925, Gillioz’s brilliantly sturdy bridges and roads connected much of southwestern Missouri, and he was interested in exploring different kinds of architecture. A group of prominent Springfield businessmen had been planning to build a vaudeville theatre and movie house downtown since 1924, but the project only picked up steam when Gillioz took over around August 1925. The steeland-concrete, bridge-like building Gillioz designed was like nothing else in the skyline. And he was adamant it be built along Route 66.

“That street in Springfield was already fully developed, so M.E. bought the piece of land closest to it,” Steele said. “He signed a hundred-year lease with a laundromat one block removed to get the address that was on Route 66. Our lobby is seven feet wide and eighty feet deep and extremely narrow because it used to be a laundromat.”

The unusual, eye-catching building drew the gaze of tourists on the Mother Road, who crowded in to watch the daily matinees. Gillioz quickly realized that the theatre, which hosted vaudeville acts and screened silent films before transitioning to talkies in the early 1930s, had two audiences. In 1926, Fords did not have air conditioning and people needed a place to stop in the heat of the day.

“Our theatre started showing things at eleven o’clock in the morning and eleven o’clock at night,” Steele said. “People traveled in the cool of the morning and stopped for lunch and they would move on in the evening hours. Then our second audience came into play. After dusk, the farmers and people from Springfield proper would go out for the evening.”

The Gillioz operated from sunup to sundown for almost sixty years. During World War II, the theatre hosted songfests to boost public morale. Gillioz passed away in 1962, but his theatre continued to be a place where visitors could join the community for a few hours and forget about their troubles.

In the early 1970s, the interstate bypass and urban sprawl combined to draw people away from the historic theatre. Businesses in downtown Springfield shuttered their windows and the Gillioz followed suit in 1980. “The thing that saved [the theatre] was that it was really overbuilt,” Steele said. “Gillioz built the theatre out of what he knew, which was steel and concrete and plaster over it. Other than the doors, the banisters, the armrests, there was virtually no wood. If it had been made of wood during those 26 years that it was empty, there would have been nothing to save.” Gillioz’s unique architectural style saved the building, but it also attracted a significant vagrant population. Pigeons dipped through the collapsed ceiling and squatters scrapped Gillioz’s organ for parts. Attorney and downtown enthusiast Sam Freeman was the sole protector of the abandoned theatre. “There are stories of Sam chasing some of that vagrant population down the street that had stolen some of those organ pipes,” Steele remembered. In 2006, Freeman was increasingly concerned that the historic institution would be torn down. He went to local oilman Jim D. Morris, who owned the front and back door of the laundromat-turnedtheatre, which Gillioz had leased. When Freeman asked Morris to buy the Gillioz, Morris asked, “Why would I want to buy an old theatre?” “Sam’s response was, ‘Because if you don’t do it, it’s going to be destroyed.’ Jim’s on record saying, ‘At that point, it became a heart issue and not a business issue.’”

Shortly after that meeting, Morris bought the theatre and reopened it as a non-profit on October 13, 2006. Today, the old marquee lights up with an array of international artists and movie festivals. While the eleven-to-eleven schedule is a thing of the past, travelers on Route 66 are still inevitably drawn to the majestic Gillioz, a living testament to the fact that where the Mother Road’s two lanes cut through the American landscape, art inevitably springs forth.

The Roarin’ 20’s

On the corner of West Santa Fe Avenue and 3rd Street in Grants, New Mexico, a sign, whose showy design stands in stark contrast to its weathered condition, overlooks an empty, graveled lot. The sign, organically shaped by a border of yellow rope, bears the words “ROARIN’ 20’s” in a dashing white font against a faded red background, with a single white panel stating “The” in black text above. Today, this sign is all that remains of not one, but two establishments that once thrived right alongside Route 66.

The Roarin’ 20’s was—as denoted by the rectangular sign below the iconic title—a bar, grill, and speakeasy—a style of restaurant that emerged during the actual 1920s as an illicit retreat for those seeking alcohol and intimacy during the years of Prohibition. While the first record of The Roarin’ 20’s dates back only as far as the ‘60s, long after Prohibition ended in 1933, the establishments still sought to mimic the ambiance of speakeasies, originally to a T.

“The Roaring Twenties sign was originally from an Albuquerque night club, which boasted beautiful topless waitresses,” recalled Paul Milan, former President of Cibola County Historical Society. “We found this out by mistake— another couple, a friend, and my wife decided to celebrate at this new, attractive club, and were surprised when the waitress simmered up to our table. We had never tasted a martini and decided to try one. The other couple’s husband and I kept ordering martinis, since the waitress would approach us, right under our nose, and we said yes without thinking. It was a tough night and I never had another martini.”

The Albuquerque location on East Central Avenue closed not long after the Milans’ visit. The sign was salvaged by Eddie McBride, who had moved from California with his wife, Dora, to take over his father’s operation in Grants—an old, mom-and-pop, New Mexican-styled hangout called the Sunshine Cafe, Bar, and Dance Hall, which, fittingly, actually had been built during the ‘20s. McBride updated the building for the uranium miners who were sweeping through Grants at the time, adding tablecloths to the tables and installing a drive-up window. Outside, McBride erected the Roarin’ 20’s sign and saw fit to rename the restaurant after it, albeit with “Eddie’s” added beforehand—displayed on the rather out-of-place white panel that instead reads “The” today. So it was that Eddie’s Roarin’ 20’s resumed the business that started in Albuquerque, minus the topless waitresses. “After the McBrides, a schoolteacher and his wife [Walter and Ida Candelaria] bought [the restaurant], and then Georgia [Romero] and her husband [Escolastico “Lucky”] bought it in the 1990s,” said Chris Roybal, Marketing Director for the City of Grants. “It never changed after that; it was always some type of a restaurant and bar, [and] it’s always been called The Roarin’ 20’s since then.” The Romeros owned The Roarin’ 20’s until the early 2000s, when the nation encountered an economic downturn. Liquor licenses became highly profitable when sold to supermarkets, so the Romeros sold theirs to the Walmart Supercenter in Grants, ending one of the restaurant’s main draws—as evidenced by the third sign down the signpost that reads “Package Liquors.” No longer seeing the merit in keeping the establishment, the Romeros sold it to a man named Alfred Mirabal, who has left it untouched ever since.

By 2015, the restaurant had seen too much wear and tear and was torn down, leaving the lot empty except for the sign and its post.

The decade the sign alludes to was a time of expansion for America, filled with new inventions, new laws– both liberating and restrictive–and a growing economy ripe for expenditures. Neon signage also began its reign of popularity, and while the sign holds no gas-discharge tubes, every inch of its white “ROARIN’ 20’s” text is lined with light bulbs, imitating the extravagance embraced during the era.

“From what I remember—it’s been 20 years since [my husband and I] ate there—the lights on the outside chased each other,” said Roybal. “I’m assuming they [still work, but] I’m not sure there’s power to them. We are hoping to open a neon park here, but at this time, infrastructure comes [first]. We get a lot of tourists because of this one sign.”

The Roarin’ 20’s sign speaks to an era when Route 66 was just a work in progress, as the country was beginning to open its eyes to a world beyond the homestead. Not everyone was on board with the radical changes brought on by the decade, but there is little doubt that the ‘20s cemented their place in history, much like many locations on the Mother Road. It would be a terrible shame if this sign was to fall by the wayside as both of its restaurants have, and hopefully it will be preserved along with many other relics of this expansive age. If the proposal for a neon park reaches fruition, Grants, New Mexico, may have an even brighter future.

CARTHAGE NOSTALGIA