16 minute read

GOING INDIANA JONES

When science collides with the ocean, all kinds of things can happen. Many of them are great for the environment, some are personally life-changing and a few will get your adrenaline pumping. To inspire the next generation of marine science whiz kids, we’ve collected a few tales from the sea. Each experience is a real event related by someone who has dedicated their life to making the ocean a better place.

Growing up on the coast of Southern California, I spent a lot of time on or in the water—fishing, body surfing and diving. Not wanting to leave the coast (and my favorite pastimes), I headed off to the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), as an undergraduate. Like many of my classmates, I majored in biology and had aspirations of going on to medical school. So, during the spring of my junior year, I applied to several of the University of California medical schools. At the same time, I was also looking for a summer job. Inasmuch as my ‘62 Volkswagen Beetle had just died, I was

restricted to potential employers that were within bicycling distance of downtown La Jolla. I got lucky.

I had inquired about summer employment in a few labs at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, but there weren’t any positions available. Then, it just so happened that a fisheries biologist at the National Marine Fisheries Service’s (NMFS) lab in La Jolla called one of those labs to see if they knew of an undergraduate who would be willing to work on a project. The study involved the analysis of underwater photographs taken by a free-vehicle “drop” camera. The camera was deployed off a moving research vessel over “acoustic targets” (fish schools) that were detected by sonar. The camera would slowly descend through the water column, taking a total of 36 photos, before releasing its ballast

and floating up to the surface. My task was to determine what information we could get from the photos—hopefully the species composition of the school, and maybe the density (spacing) of fish within the school.

I spent my first few weeks of the summer digitizing photographs and calibrating the camera in the UCSD swimming pool. Then I got an opportunity to go on a week-long cruise on a NMFS research vessel off Southern California to drop the camera on fish schools. Things worked out pretty well on the cruise. I was able to make several successful camera drops on fish schools during the week, although the camera “forgot” to return to the surface on our second to last day. From the photographs I got, I was able to not only identify the schools from the pictures (most were northern anchovy or jack mackerel), but also to estimate the density of fish in the school. Having demonstrated the potential of the system, a few more camera systems were built and I was invited to participate on another NMFS research cruise at the end of the summer, this time for three weeks in the waters near the Channel Islands. That second cruise was incredible. We spent a lot of time underway, doing acoustic transects and camera drops, but on several occasions we anchored up near one of the islands for the evening. During that down time, I was able to use a smaller vessel to go diving in the kelp beds for abalone or to fish for kelp bass and California halibut. On the third week of the cruise, we ran into a massive concentration of anchovy schools near Pirate’s Cove on Santa Cruz Island. The anchovies were so tightly packed throughout the water column that the sonar return suggested it was land! As anchovies are a forage species for all kinds of birds, mammals, and fishes, the amount of wildlife in that area was unbelievable. Diving birds were everywhere, as were several species of dolphins, the occasional whale and schools of large, white seabass. When we first stopped in the area, I deployed the drop camera on a tether. As I was doing so, an off-duty crew member dropped down a diamond jig and instantly hooked up to a white seabass. Then another crew member did. I quickly retrieved my drop camera and grabbed a fishing rod. Dropping down a live jack mackerel, I was hooked up before my bait hit the bottom. My first white seabass was 51 pounds! As I looked around at all that was happening, I remembered thinking that I was actually getting paid to do this. Why would I do anything else?

John Graves never made it to medical school but went on to get his Ph.D. at Scripps Institution of Oceanography and began a lifelong career in fisheries research and management. He is currently chancellor professor of marine science and chair of the Department of Fisheries Science at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William & Mary, and for the past 21 years he has served as the chair of the U.S. Advisory Committee to the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas. Below: Early in his career, Dr. John Graves—smiling here over a nice catch of mahi—decided to trade a stethoscope for a camera and a fishing pole.

Not all research is in the lab. For Dr. Steve Gittings, scuba diving has been a regular part of his scientific career and he’s found it can sometimes require a bit of nerve.

Early in my career, I got into a situation that made me feel the same fear I imagine a tangled whale might experience. It was 1983 and I was in Cameron, Louisiana, installing experiments around a brine discharge pipe that was part of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve Project. Diving in only 15 feet of water should be a walk in the park, right? But add mud until you have zero visibility and no light, a pipe spewing thousands of gallons of brine through a fire hose, a snagged shrimp net, a mess of monofilament, a mesh goody bag, and an untested young diver, and mix them together (literally, as I did), and 15 feet of water might as well be a mile. Somehow I got myself above the discharge pipe, began tumbling like I was in a dryer, and became hopelessly tangled and disoriented.

This isn’t part of your dive training, but it is where you learn to dive. It’s also where you get an idea of how you’ll handle real pressure. Bad thoughts creep in. “Did I start with a full tank? Will my buddy have any idea what’s going on? He might even be having the same problem. Either way, he’ll have no idea about my predicament until it’s too late. I’m breathing too hard. Is that my octopus free flowing? How much air do I have now? It can’t be much.” You sense the threshold of panic. Will you cross it? To your surprise, your mind suddenly opens to a more useful thought. “If I can just drop below this gushing brine, I can find a calm spot on the bottom and deal with this.” With a few awkward moves that, thankfully, no one will ever see, you make it happen. On the bottom, your roving hands confirm that there is only one choice. Find that knife on your leg, grab it tighter than you ever have before, and start cutting everything you didn’t bring in your dive bag. It’s all by feel. “Do NOT drop that knife!” The mud below would swallow it faster than quicksand. Slowly but surely you cut, trying to ascend every few cuts to see if you are free. “Stay away from the discharge.” You drop back down and cut some more. You promise yourself, or a higher authority, that if you get out of this, you won’t push your luck here again. Something works, and you suddenly find yourself floating the last couple feet to sunlight. A crisis becomes just a story. In diving, the distance between safety and disaster can be just a few feet. It’s even less if composure turns to panic. On that day, I learned a little about where my threshold is and it gave me confidence that I had a bit of the right stuff. I was able to repel panic by focusing on productive thoughts. It was an important experience. In many ways it launched me into a career full of what I call “life experiences.” They’ve included witnessing some of nature’s greatest spectacles, like mass coral spawning and huge fish spawning aggregations, living several times in an underwater habitat, and diving in five different submarines—all alone in one of them. Over the years, I’ve had a few more opportunities to panic. I didn’t. I don’t look forward to them, or enjoy them, but I believe it helps that I’ve been tested before and passed.

Dr. Steve Gittings is chief scientist for NOAA’s National Marine Sanctuary Program. He works with the program’s scientists to better understand sanctuary ecosystems, track changing conditions and reduce human impacts. From 1992–1998, he was manager of the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary. He received a B.S. in biology at Westminster College, and M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in oceanography at Texas A&M University.

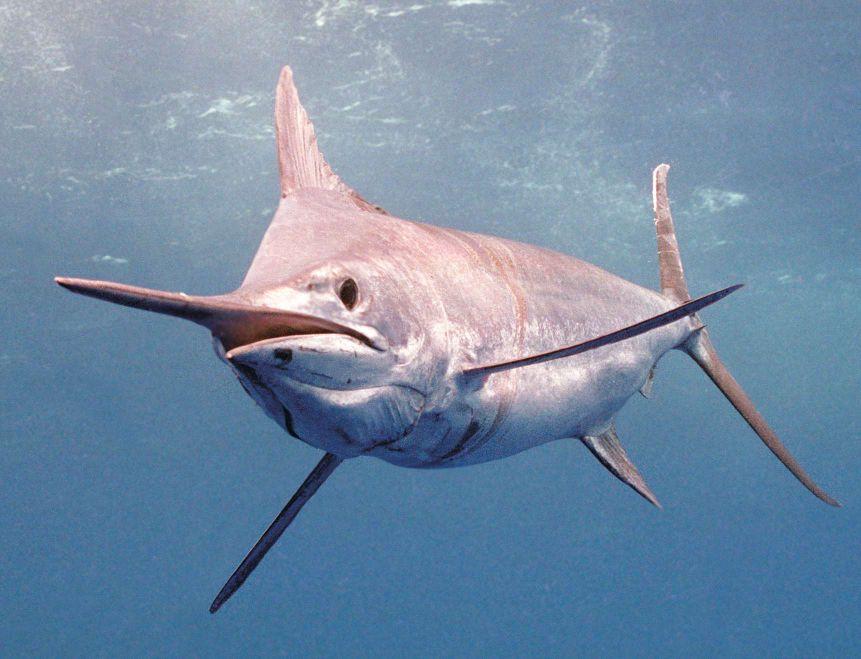

Are you on a first-name basis with a tiger shark? Emma is a regular subject of shark research conducted by Dr. Harvey and others in the Bahamas. Below: Guy captured this image of a free-swimming marlin on one of his many expeditions. He says opportunities to view his subjects in this way helps him create such detailed and lifelike art. Photo: Guy Harvey.

Sitting on the covering board in my dive gear, camera in hand, I was watching the teasers intently. The bubbling left teaser was suddenly engulfed by a black mass, dorsal up and bill out over the lure. Blue marlin!

I slapped on my mask and launched into the water, getting below the boat’s foamy wake to face the oncoming fish. Coming right at me, the big marlin was chasing the teaser and passed a few feet over my head. What a shot!

This close encounter represents the culmination of a lot of planning, time and effort that ends in the desired result: capturing the image of a free-swimming marlin. The large oceanic fishes, sharks, billfish and tuna cannot be kept in captivity. You have to visit their realm to see them. They are fast, elusive and inhabit the remote depths of the ocean. Consequently, they are also difficult to study. As an artist, I am hoping to get a glimpse of these majestic creatures in their natural habitat, not on the end of a fishing line. I have only fleeting glimpses of these fish as they come and go. Some big sharks however, like tigers, makos and oceanic white tips, can be chummed in using scent to initiate the encounter and then prolong the interaction. Chumming for big sharks is an effective way of not only getting them close for photography, but also for catching the animal for deployment of electronic tags. In Bermuda, we chummed tiger sharks, dived with them and then caught them to deploy SPOT

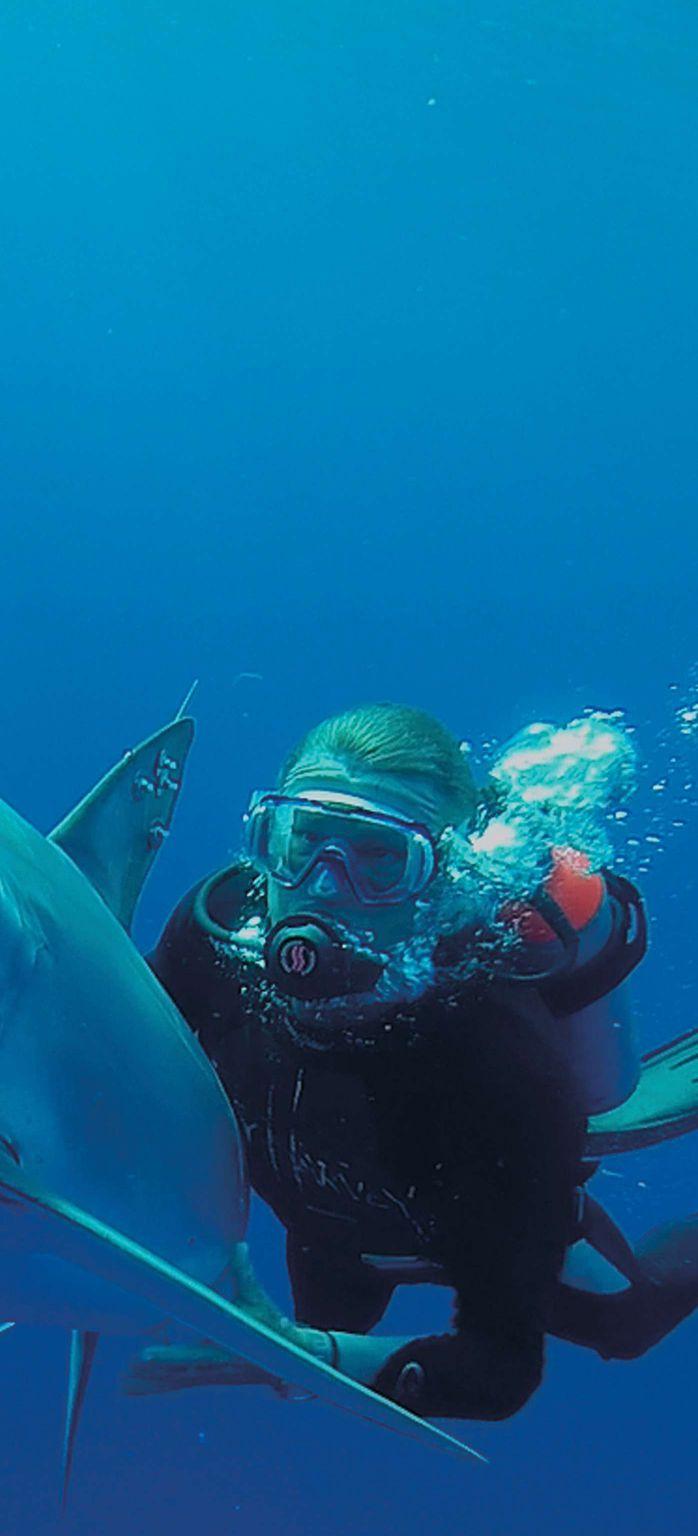

A videographer gets amazing shark footage at Tiger Beach in the Bahamas. It has given Dr. Harvey and others a unique opportunity to study these animals up close. Photo: George Schellenger.

tags prior to release. In Mexico, we chummed makos in for the same reason, only back into the cycle, which is repeated many times for the day. At around 1,200 lbs., we use cages, as the makos are lightning fast, and when amped up, they bite she is formidable. She carries the scars (in varying states of repair) of many mating everything around them, including the cage. skirmishes with male counterparts.

One the best shots to get is the departure of the fish having been tagged. Emma gives divers so many options for great photos with an impressive tiger The marlins and sailfish are revived by towing them next to the boat at a slow shark in the wild and in complete safety. She has become the silent mascot for speed, holding their bill and dorsal fin upright. This forward motion drives water sharks in the Bahamas and even has her own Facebook page! She is the star of over their gills. Billfish, tuna and large sharks are ram breathers. That means they not one but two documentaries produced by George Schellenger. There are other cannot pump water over their gills—they must swim forward to breathe. large pelagic animals that are easy to dive with if you know where to go. Whale

Once the billfish is revived, I sharks congregate off the coast of the position myself under the boat to get Emma gives divers so many options Yucatan in June to August each year, the shot of the fish swimming away. and access is through snorkeling. Giant Its colors light up, the tail is swinging for great photos with an impressive manta rays are also present. Mantas and it heads down into cooler water are also seen in the course of diving in as I swim beside it, and I hold the tiger shark, in the wild and in various locations worldwide such as in shot until it disappears into the blue. the Galapagos and off remote western We use the same process for tigers, complete safety. Pacific islands. makos and oceanic white tip sharks. Expeditions to catch, tag, track, film However, some makos are not so ready to leave the scene and often swim back at and photograph reef ecosystems and large pelagic species are multi-disciplinary. us to check out what is going on, providing more great footage. For me, the most exciting and enjoyable part is being inspired by new encounters.

The ultimate close encounter is always at Tiger Beach in the Bahamas. Diving I am always learning more about the ocean and its amazing inhabitants. with renowned photographer and shark conservationist Jim Abernethy has always been a huge learning experience. He specializes in getting his clients in Dr. Guy Harvey paints such accurate representations of his subjects—billfish, sharks, front of bull sharks, hammerheads and tigers. From June to November each year, dolphins, turtles, etc.—because he’s an avid diver and underwater photographer, his favorite shark, Emma, a 14-ft. tiger shark, shows up in the chum line. We had not to mention a Hall of Fame fisherman. Diving has allowed Guy to get up close the pleasure of spending a day with Emma in June. and personal to marine life in its natural environment, both to further his art and to

Emma has been known to Jim for 13 consecutive years as an adult shark, conduct tagging studies and other research. Dr. Harvey studied at Aberdeen University which means she is now probably 25 to 30 years old. She is different from all the and earned his Ph.D. from the University of the West Indies. other tigers because she swims up the runway and then makes tight turns to get

For the past five years, I’ve been fortunate to document Guy’s expeditions to explore the underwater world—from tiger sharks to shortfin mako sharks and from blue, white and black marlin to the curious Nassau grouper. My memories are indelible and the work is always rewarding. But the question I’m asked most is, “What’s it like to work with Guy?” The best way to really describe Guy Harvey—at least as an artist and researcher—is to go over five things I’ve learned by watching him work.

When we’re on the water and the lines are out, Guy is focused on what will happen next. He’s making adjustments to the bait or teasers, constantly looking for any signs of life just beneath the surface. His daughter Jessica and I watched him in Panama as he sat on the transom hour after hour, day after day, patiently waiting for the flash of blue. When a blue marlin shows up, it all pays off in an instant. Guy is smiling, incredibly excited—and we see a glimpse of Guy as the young man who read Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea dozens and dozens of times. Guy’s patient persistence pays off for science as well. He’s spent more than two decades working with Dr. Mahmood Shivji and other scientists, and part of that that time has been spent tagging and tracking tiger sharks to better understand how to protect these creatures. That work helped the government of the Bahamas turn their waters into a shark sanctuary. Now he is exercising the same patience as GHRI tracks oceanic whitetip sharks. I’m always eager to see a new piece of artwork from Guy. A flood of questions goes through my mind as I take it in: How did he paint the background? How does the light filter through the surface of the water? What kind of action is he detailing? What will happen next? If you study a Guy Harvey painting, you’ll see life in motion captured by every brush stroke. Detail, detail, detail. Each painting is the result of a lifetime of craftsmanship and a lifetime studying science and witnessing these creatures first-hand. It goes way beyond the 10,000-hour rule. As you look at Guy’s artwork, you have to ask yourself, “Do I allow enough time to be detailed in what I do? Or am I too distracted? How can I stay focused on the detail?”

Guy is hard on himself and his work. He wants to be everywhere at once, he wants to shake hands with every fan and learn their names, and he wants every painting to be perfect. Not to mention, he wants to spend as much time as he can on the water for a chance meeting with a marlin. This is the passion you see every minute when you’re with Guy and in every painting he paints. During our yearly oceanic whitetip shark expeditions to Grand Cayman for the Kirk Slam Fishing Tournament and the Cayman Islands International Fishing Tournament, Guy is passionately asking anglers for their help in finding the once common oceanic. By the time each tournament starts, Guy has spread his passion to the anglers and the spectators. They become eager to help our cause. Guy’s passion is changing research by encouraging more people to become citizen scientists.

The variables in the field are always in flux. Guy is not. Guy’s consistency is the foundation for every expedition. He takes nothing for granted and works hard every day. He knows that each second we spend on expedition is a priceless opportunity. Every encounter with a large pelagic animal is as important to Guy as the previous encounter.

What really drives Guy? I think it is his faith that if you do the work, everything will move in the right direction. If you lead the way and lay the foundation, then others will follow. It’s what makes an icon like Guy, iconic.

George C. Schellenger is a two-time Emmy Award-winning producer. He’s worked for the X PRIZE Foundation, AOL Time Warner, Microsoft and NBC. You can see his work with Guy on iTunes. George and Guy are currently working on new programs for November’s Shark Talk in the Cayman Islands. Left: George Schellenger (foreground) shoots a selfie with Guy and his crew. Schellenger has partnered with Guy on numerous film projects, including those focused on shark and grouper conservation.