25 minute read

WINDMILLS AT SEA

Offshore Windfarms

GRACIOUS GIFT OR TROJAN HORSE?

BY NICK HONACHEFSKY

Offshore wind farms have been established in Europe, most notably Denmark, since 1991, and the first offshore wind farm has already been planted in the U.S. The Block Island Wind Farm off the coast of Rhode Island, consisting of five, 6-megawatt turbines with submarine transmission cables, lies three miles off the island and allows angler access, as of now. According to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), engineering plans for the near future consist of building a wind farm off of Long Island, NY, complete with 15 wind turbines, an offshore substation, and the 30-mile power cable that will run to East Hampton, NY, as well as wind farms 10 to 20 miles offshore of New Jersey inclusive with offshore substations and subsea cables. The Block Island Wind Farm has only been operational for two years, so no hard data has been collected on the long-term impacts to marine life. BOEM is also reviewing the electromagnetic field (EMF) effects of the transmission line on sea life. Wind farms have a projected lifespan of around 25 years. So, are offshore wind farms a good or bad proposition? I recently attended a meeting in Toms River, NJ, with representatives hailing from the windmill companies Orsted, Equinor, EDF Renewables, Anglers for Offshore Wind Power, and a general public attendance of recreational and commercial anglers. Here were some pros and cons.

Photo by Martin Nikolaj Christensen

+ PROS

Clean, safe energy — Offshore wind farms produce relatively cheap, renewable, clean energy that benefits a community. Unlike offshore oil platforms, there is no chance of an oil spill or explosion that would destroy the surrounding ecosystem and wreak untold, ecological damage. No doubt, that is peace of mind when considering the implementation of energy sources.

Also, the growth of renewable energies, such as wind and solar, continues to reduce our dependence on foreign oil and lower the output of greenhouse gases, which are contributing to climate change. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, more than 25 offshore wind projects with a generating capacity of 24 gigawatts are now being planned, mainly off the U.S. Northeast and mid-Atlantic coasts. That is enough energy created by the wind to power almost 20 million homes and eliminate the burning of more than a million gallons of oil per day.

Fishing potential, submarine growth — Much like the oil rigs out in the Gulf of Mexico, California, and other regions, years of operation in the marine environment will collect sustained marine growth on the structures, in essence creating a contained ecosystem, with which the cycle of life attracts. Windmills could become a little oasis in the ocean where barnacle and mussel

growth will bring crabs, sea worms, and baitfish, thus attracting gamefish like tuna, striped bass, blackfish, and such. That kind of life adds up to a major fishing platform. Paul Eidman, charter boat captain and spokesperson for Anglers for Offshore Wind Power, has fished the Block Island turbines and states. “There are already four tons of mussels growing on each of the Block Island turbine stanchions,” he stated. “Once the mussels take hold, it goes right up the food chain. We’ve had great days fishing for sea bass already there.” Angling potential increases and the platforms can offer a great fishing opportunity in an otherwise barren ocean area. Windmills slated to be built in New Jersey are projected to be laid out in straight lines, .71 to .78 miles apart, to allow for commercial clam dredgers, scallopers, and squidders to effectively work their gear through the area.

Photos by Peter Southwood

- CONS

Environmental and biological impacts — Of utmost

concern among the public is environmental impact. “There’s a lot being proposed to go out in the ocean and on the bottom,” said Tim Dillingham of the American Littoral Society. “The construction of undersea cables, as well as the windmills themselves, will disturb a lot of submarine ground.”

The ocean is a delicate place. Unlike wind farms on land, marine mammals, fish migration, and life patterns may be disturbed. Some have concerns that vibrations of the turbines and EMF pulsing could disrupt whales, tuna, sharks, and dolphins. Also, seabirds could be negatively affected. Turbines are massive structures, with height spans between 580 feet and a maximum of 840 feet tall, that could impact bird migration or cause issues that have yet to be identified. At this point, the science is in the gathering process and is too young for us to know how windmills will impact marine life.

“You’re talking about a forest of these turbines, not just one or two, here and there,” noted Robert Rush, Jr., of United Boatmen and a member of the New Jersey Marine Fisheries Council, while speaking to the windmill companies. “We haven’t seen the science yet, any scientific data, for potential effects on the region’s fish populations. If you can’t show the science, we’re not on board.” Representatives from Orsted admitted there was no scientific data that addressed how the turbines EMF and vibrations would affect fish migrations and populations. However, a study on Denmark wind farms found a direct correlation between the strength of EMF from undersea cables and increasing avoidance behaviors around those cable and decreasing catch of flounder.

“Even if you take one fish species out of the food chain from the EMF’s influence, it will affect the entire ecosystem,” added Rush.

Submarine cables running to the windmills will be buried six feet under the sea floor, possibly destroying indigenous mussel beds and prolific submarine substrate, but Doug Copeland of EDF Renewables assures they are taking that into consideration. “All windmills and construction will be responsibly sited,” said Copeland. “We will actively research seafloor mussel beds, structures, and shipwrecks so as not to disturb habitats during construction.”

With plans to construct the windmills in just 60 to 100 feet depths in South Jersey, some wonder if a hurricane or nor’easter, with the punishing power of Superstorm Sandy, would damage the structures. They are built to withstand hurricane force winds, but nature has shown how unforgiving she can be.

Angler access — Will the windmills be off limits to sport fishing? Angler access is the number one concern for recreational fishermen. Post 9/11 along the NY/NJ area, things are still a little locked down, more so than other areas of the country. Many security protocols have been implemented for structures and transportation avenues along the metro shores. That said, with energy-generating platforms lining the sides of major international trade shipping lanes, you would expect some security measures would eventually be put into place. Therefore, anglers are concerned that to sell the wind farms, wind companies are pandering to the angling community allowing them to fish by the structures carte blanche.

“We have no intent to shut off any angler access to the windmill platforms,” stated Copeland. But many anglers are worried that it’s only a matter of time before federal, governmental (e.g., Homeland Security), or private windmill company restrictions come into play, closing off sections of the ocean to fishing.

When pressed for more information on angler access, Copeland stated, “We know that there will be safety zones implemented around the substation platforms. We do not know how wide the zones will be yet.” Anglers voiced an opinion they want a written guarantee that access will not be limited.

Socioeconomic issues — Unsightliness from shore, aka “Visual Pollution,” is also a concern to the state’s economy. The bulk of state tourism along the East Coast, especially in New Jersey, is dependent upon the shoreline view. According to BOEM, wind farms built within 26 miles offshore can be viewed from shore on a clear day, which has the potential to negatively affect tourism and property values.

Offshore wind farms have the potential of reducing the threat of oil spills and reducing our dependence on fossil fuels. They also will provide a habitat for marine life and potential new opportunities for angling. However, moving forward with the complete science, not to mention the impact on the submarine biomass, begs the question: are we moving too fast into uncharted waters, so to speak? A segment of the fishing community has come to the conclusion that we should wait until legitimate scientific data comes in, in respect to environmental and biological impact, before any state further commits to mass production and leasing of lands to offshore wind farms.

Of course, when energy is at stake—whether it’s fossil fuels, wind, solar, or nuclear—the path forward may not always be simple or easy.

Photo courtesy of www.cgpgrey.com

Photo by Martin Doppelbauer Photo by Hans Hillewaert

Suzan Meldonian

a photo portfolio of black water diving

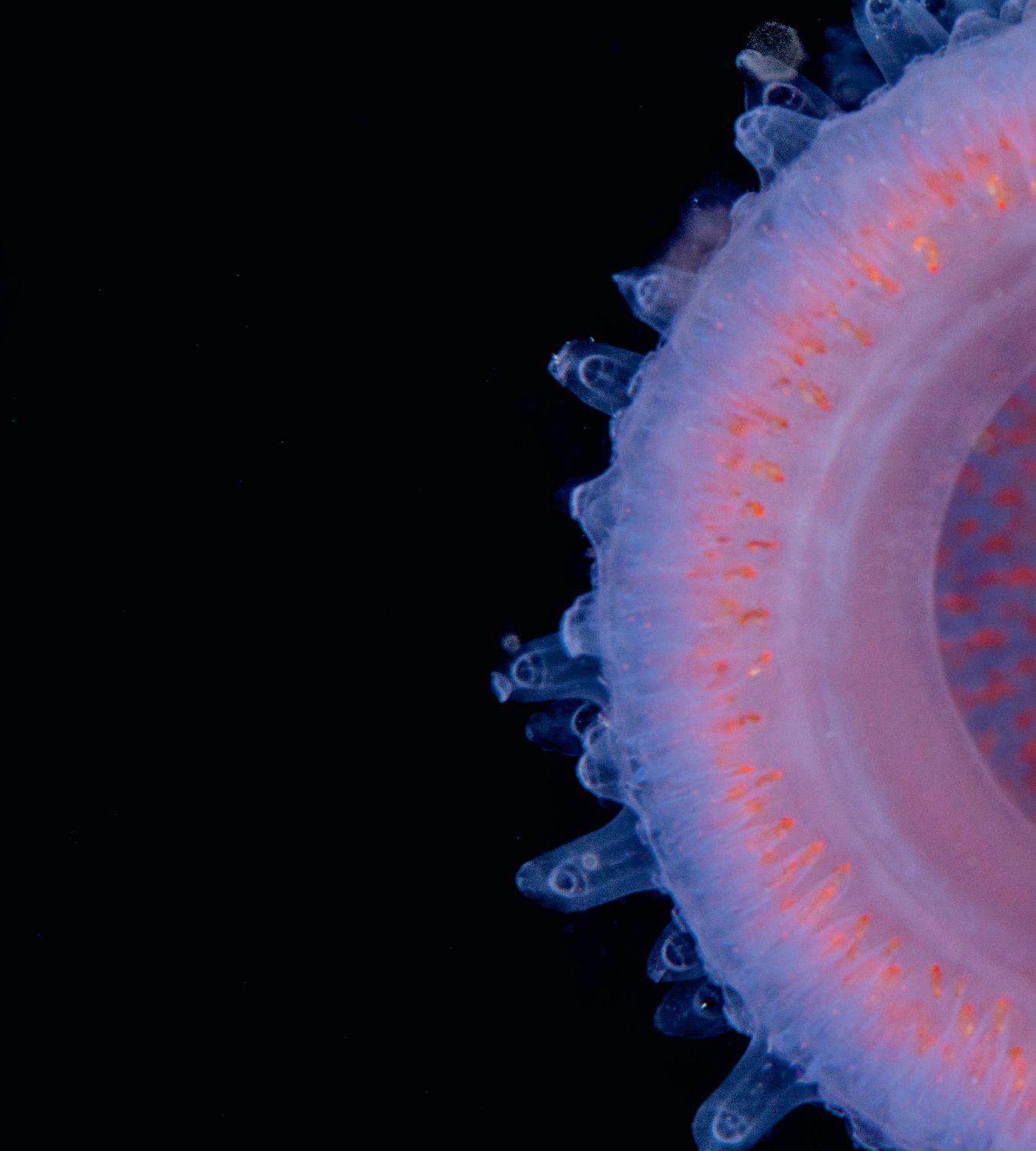

A pink, tubular pyrosome becomes a protection home for juvenile pin fish in the Gulf Stream current. Pyrosomes are actually colonial tunicate colonies made up of thousands of individuals called zooids.

Right: Tube anemones are one of the many gelatinous creatures floating around out there in the gloom. Constantly changing shape, the pinkish area is most likely what it had for dinner.

Below: Here, we see the tube anemone has pulled in its tentacles. Perhaps no bigger than a pin head, this is just another layer of the ocean.

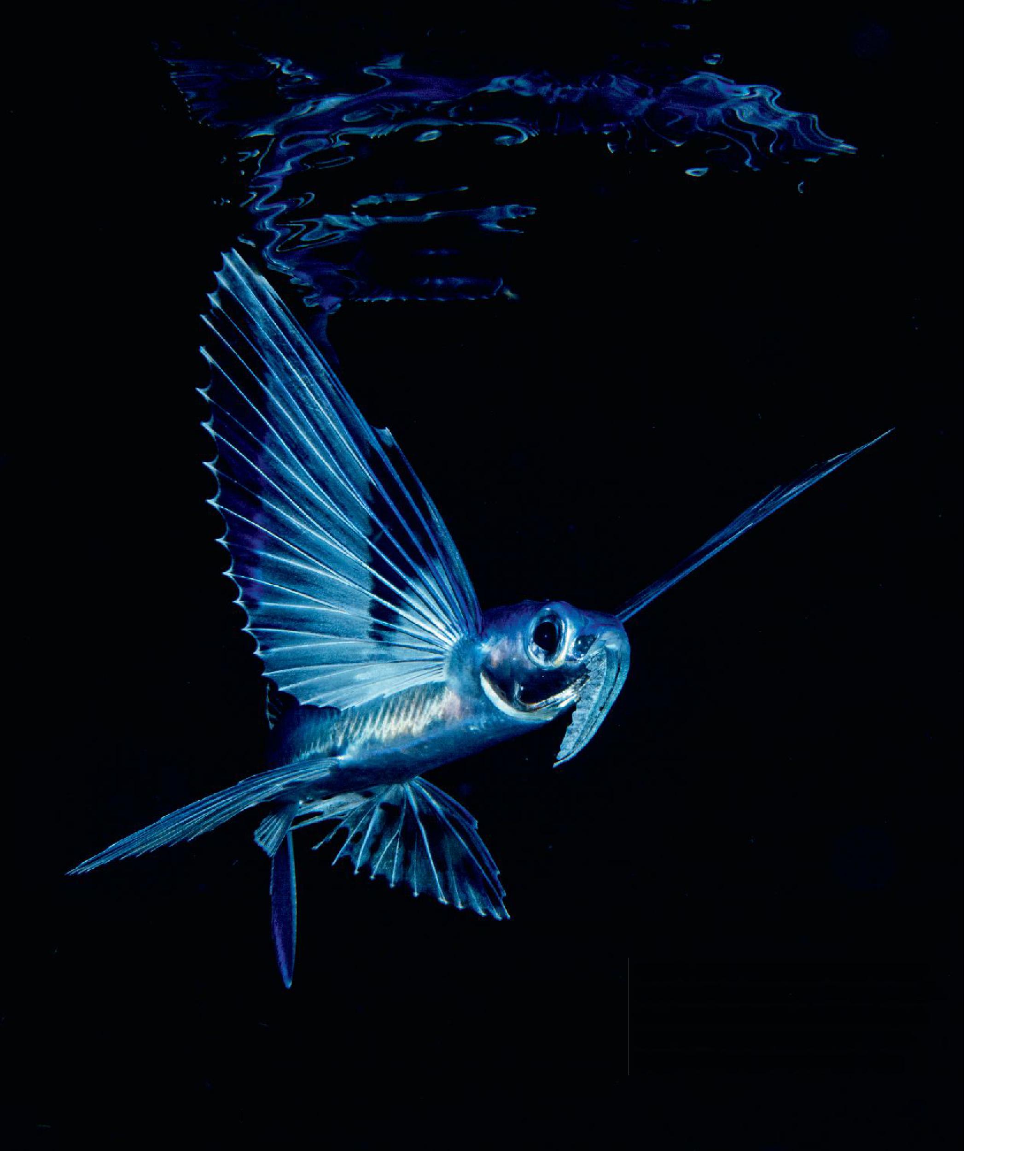

Flying fish - Atlantic - Cheilopogon melanurus. We’ve seen them fly out of the water and into our boats, but remarkable as it is, they seem to fly underwater as well, hovering close the surface. This one is known locally as the Fu Manchu flying fish with these long proboscis used for probing.

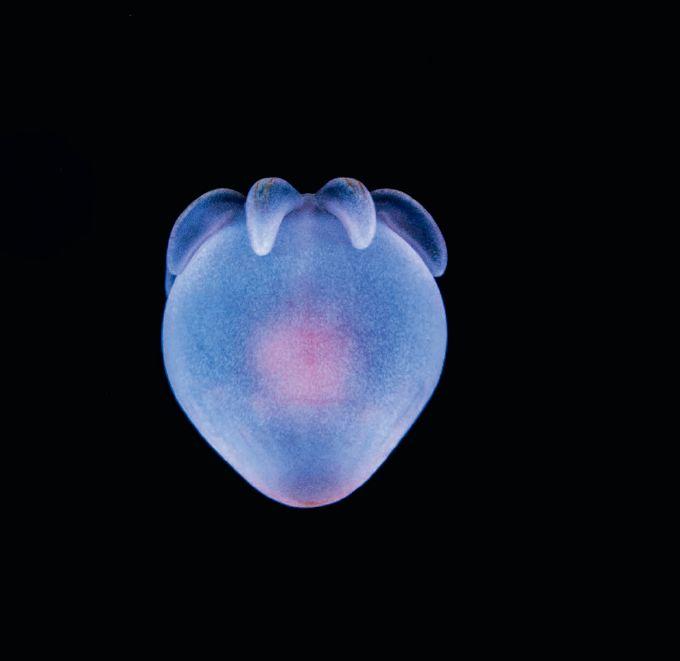

Snails actually begin their lives with sparkly wings, which will later develop into one foot. They use these to flap around and propel themselves through the water column.

Even at this early stage of their lives, and no bigger than the sliver of your fingernail, wahoo are born with all their teeth. Photographed with a 10x diopter on a macro lens. Even the massive, strong tuna have to start somewhere, with nothing more than a jawful of teeth and tail. Hard to believe something so small will grow into such a strong and powerful fish. Size is less than one inch.

A very tiny jellyfish, no bigger than a grain of rice. Photographed in the Gulf Stream current, this was a very exciting find for scientists in Japan. Scientific papers have now been written up on this find with the image proving its existence in the Atlantic, when it was only believed to have existed in Japanese waters.

Left: Without getting too technical, the oceans are filled with a vast variety of worms. Many of them have highly toxin-bearing quills filled with nematocystic venom. This little squirt was spinning in place, doing barrel turns at a ripe age of perhaps three hours.

Right: This is a larval spotfin flounder, Cylopsetta Fimbriata. It is about the size of a quarter but as thin as a piece of paper. In their larval stage, their eyes are on either side of their face, but as they grow older, one eye will slide over for its adaptation to its sand dwelling life with both eyes ending up on the same side of their body to keep an eye out for predators and mates. It is unknown why this creature has such an elaborate headdress, but it is quite beautiful.

This pelagic blanket octopus is a rare sighting. Females grow to a staggering six feet but may look like a discarded rag on the surface to boaters. Regarded as highly intelligent creatures, not only do they have the ability to detach a tentacle to flee a predator, but they have been known to use the stinging tentacles of the Portuguese Man-O-War as a defense mechanism.

Even at this pre-settling stage, the lionfish have invaded our waters and come up to feed during the vertical migration, equipped with their voracious appetites able to consume 20 larval fish. Also quite toxic, it is very important not to touch their dorsal fins or near their head as their venom is extremely painful and, for some, can be fatal.

Squids are actually mollusks. The bigfin reef squid is a commercially important squid commonly found throughout Southeast Asian waters.

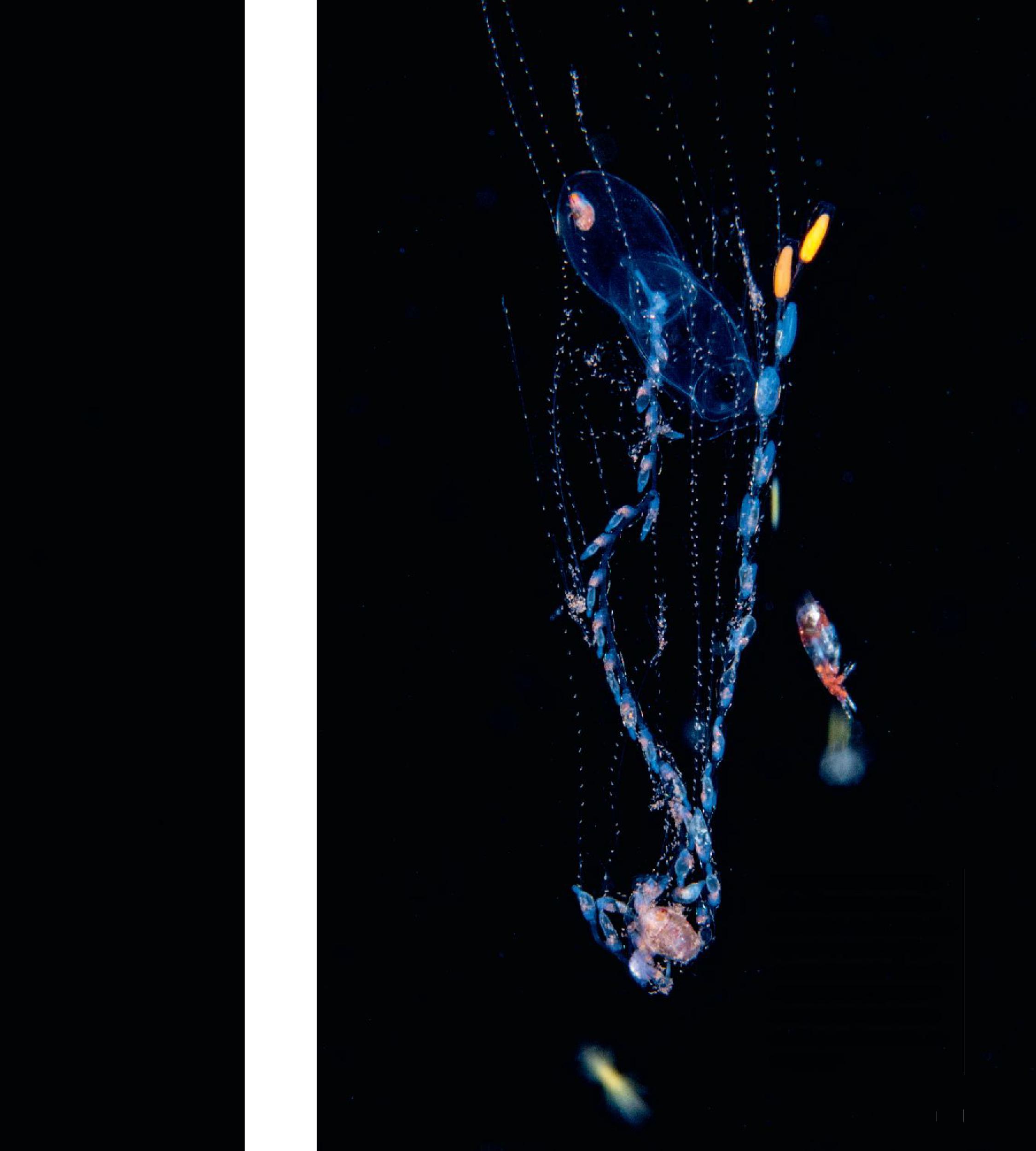

It is a dog-eat-dog world at night when all the little creatures come out for dinner. Here, a Siphonophore, a type of nearly invisible jellyfish, ensnares a larval crab that is eating amphipods. Also highly toxic, this animal is perhaps responsible for many stings—when you didn’t see what got you!

The pteropod, a mollusk, is perhaps no bigger than a couple of strands of hair. It is hard to believe that scientists can actually measure their shells to determine ocean acidification levels where it was found. Creatures like these are creating much of the oxygen that we breathe. Changes to the ocean environment impact their ability to grow and, in effect, the entire food chain relies on their strength.

The World of Black Water

Diving BY SUZAN MELDONIAN The Little Things that Count

From the time we take our first scuba lesson, we are taught skills to get in and go down. However, during the last several years, a new craze is storming the underwater photography scene. This is the world of Black Water Diving. No, this is not a normal night dive on a reef, but diving at night over depth. Depths of perhaps 600 to 1,500 feet! It certainly is not for the faint of heart, and is perhaps one of the most challenging types of underwater photography that exists.

Why, you may be wondering, would someone go on a dive in the blackness of night with no lights? Well, because an amazing phenomenon occurs every night, in every ocean, every sea, and even in lakes. This is called a vertical migration, also known as the diel or diurnal vertical migration. It’s the largest migration on Earth. Zooplankton, plankton, and other pelagic juveniles migrate to the surface from the depths up and down the water column, from dusk until dawn—to feed or be fed upon. Luckily, because of their migration into shallower waters, we only have to dive to 60 feet or less to see some of the most unique and stunning creatures on our planet!

I have descended into harp strings of jellyfish tentacles reaching 30 feet in length, filter feeding to catch morsels of food. It is a sight to behold and really important to be upcurrent to avoid being snared in their stinging tentacles.

As my eyes adjust to the total darkness, armed only with the focus lights on my underwater housing and the dim glow from other photographer’s lights, we follow our down line wherever the currents take it. At first, it appears to be snowing, with white flecks of particulate matter raining downward. Then, as my eyes adjust a bit more to the complete darkness, a host of alien beings begin to appear. Some spin furiously in place, perhaps surprised by our faint lights in an otherwise dark world. Others move methodically—rippling, transparent alien forms in rhythm to the ocean’s heartbeat. Studying the tiny subjects, I am seeking specific movement, hopefully of larval fish, or better, deep sea larval fish that come up to feed. My camera is set up for super macro. Soon, massive squadrons of juvenile squid arrive to hunt and feast upon the plethora of miniature creatures. They can be quite aggressive and often bombard our bodies en masse like little raining torpedoes, inking us with a defiant look of satisfaction in their intelligent eyes as they pass. Other times, they will hover slightly just out of reach, studying us, the intruders to their blackened world. We have become the alien invaders.

Full grown reef squid photo–bombing a shot.

newborns and pelagic juveniles in a dog-eat-dog world of survival of the fittest environment. One kick of your fin can cause a host of creatures to spin and flail out of control. I cannot help but marvel at the amazing structure and perfection in their intricate designs. And somewhere in my heart, I am certain that there is much to be learned regarding things like hydrodynamics from these natural ergonomics. These creatures have been here since the beginning of time. Some resemble strings of DNA to me.

Witnessing a glass eel—that is, an eel in larval stage, all see-through with a beak and a mouthful of teeth—can set one into a good case of the giggles out of sheer delight in finding it. What amazes me most about these tiny creatures, who are no bigger than a quarter and most the size of a grain of rice, are the fancy headdresses and colored lures they behold.

And yet the ocean life continues to survive in this harshest of environments. Or does it? The ocean is so big. How do they find one another, propagate, and survive commercial fishing? So many mysteries.

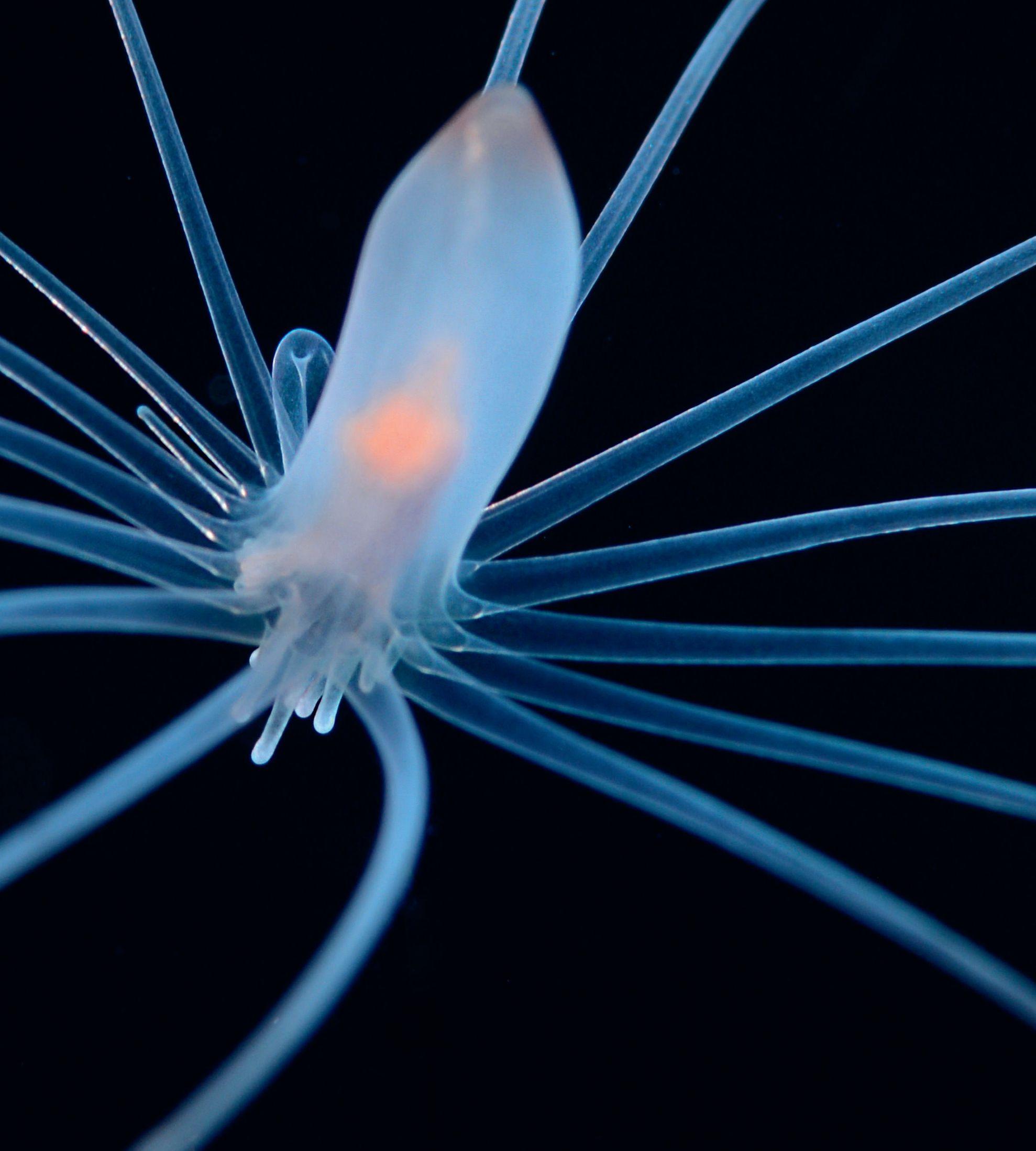

I have been engaging in this drift-diving in the Gulf Stream for about four years now, and the creatures that I am finding are absolutely astonishing! My favorite find to date is the tripodfish, and it is believed I photographed the first juvenile living specimen here off the East Coast of Florida. I call it the shot gone ‘round the world, as it went from university to university in search of a name. Finally, it was identified by David Johnson, ichthyologist, curator of fishes at Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, as a Discoverichthys praelox. This deep sea fish, originating perhaps in the Mariana Trench, was found only once before in history, originally by a Bathysphere expedition to 15,000 feet in the deepest chasm on the planet.

With each new creature that I find, hours are spent connecting with scientists from around the globe and pillaging through books trying to identify these creatures. More importantly, the more research I do, the scientist in me becomes more developed. I’d like my images to inspire more ocean students.

Simply put, this joining of scientist and photographer is clearly a type of global evolution that must be shared with everyone in order to raise the bar on our understanding of our oceans. With 72% of our planet covered in bodies of water, we have so much more to learn. In such a shallow environment, we now have the ability to photograph behavior in situ, that normally requires massive scientific endeavors. We can add to the science with our pictures. We, the photographers, can now assist and become yet another voice through our photography to inspire change in our behaviors as a planet. I can only hope that my images inspire more people to learn as much as they can about the global carbon cycle.

Clearly, we are just beginning to understand the impact of greenhouse emissions and their root causes. We talk about our carbon footprint, and are now raising a lot of concern about plastics and other garbage effects that are collecting in our oceans. But I would like to take this a little further.

While it is devastating when a whale washes up on shore, only to find 50 pounds of plastic bags in its stomach, we must also consider the molecular breakdowns of chemically produced products, even the ones we cannot see, and consider their effects on every living creature in the ocean, no matter how small.

Why should humans be worried?

Sometimes it is the little things that count. For example, scientists can measure the shells of pteropods (tiny mollusks less than an inch long) and other planktonic animals to determine the effects of ocean acidification upon the beginning of life in the oceans. In simpler terms, plankton and phytoplankton essentially eat carbon dioxide with oxygen as their bi-product. This is valuable oxygen that we need to breathe.

Having photographed small larval fish covered in fungus, I have seen firsthand that there is sickness in our oceans, and it is quite disturbing. We are taught in school about photosynthesis, plants creating oxygen, however it is now estimated that as much as 50% of the oxygen that we breathe on land is being generated by our little friends here in the sea. If their environment, the ocean, is sick from microplastics and polluted water run-off—including oil from our cars and boats—these little beings will not have the ability to grow strong enough, which, in turn, causes a shorter life cycle and highly reduces their ability to perform their duties of converting carbon dioxide to oxygen. That, my friends, is one major reason we should all be concerned.

In the meantime, our intrepid night explorers will continue to drift weightlessly in the silent blackness not completely sure what we might find but absolutely certain that whatever it is will be wonderful.

*Please note that we have a specialized dive operation that manages Black Water Diving, and we have perfected safety measures over time. There are many details that apply in order to maintain safety. This type of diving is not recommended for new or seasonal divers and you should only dive with qualified dive operations skilled in all the necessary safety measures as it is a bit more involved than regular diving and still fairly new.

Leptocelus… a transparent “glass eel.” In their larval stage, they are nothing but teeth and eyes. The rest is transparent. This unlucky chap happens to also have a parasite already attached at such an early age (resembling the orange flower).

And this is why we do this. I call this “The shot gone ‘round the world.” Top ichthyologists were stumped by this deep sea larval fish found off the coast of Florida. Considered to be the first image of this animal photographed in situ, here in Florida. It wasn’t until University of Hawaii’s Jeff Millisen, NOAA scientist Bruce Mundy, and Smithsonian’s Dave Johnson were able to ID this. Much to my chagrin, it already had a name. At first, I thought it was a larval lionfish, but the colors, polka dots, and fancy fins were so beautifully sculptured that it resembled a butterfly design more than a fish. This shot was sent to top scientists at Cornell, Duke, NOAA, Smithsonian, Nat Geo, Harvard, and University of Hawaii, and even University of Tasmania. ID’d as the Discoverichthys praecox, a type of tripodfish, which has only previously been found near the Marianas Trench in the western North Pacific at a depth of 15,000 feet and somewhere in the Northern Atlantic. So what is the larva doing here in Florida? We hope to answer these and many more questions by documenting the oceans with our images! And hopefully get a fish named after us in the long run.

Alone in the Dark

As we descend, for a fleeting moment, I think...am I joining the food chain? You never know what big predators are hunting out there in the Gulf Stream current. We’ve been approached by silky sharks, duskies, sandbar sharks, and I’ve even had one very large tiger shark come up out of the gloom like a torpedo, brisking my fins as it dove under me as if marking its territory. Definitely a heart knocking moment, especially when I realized I had drifted away from the group and was out there by myself, alone in the dark.

The big predators are nearly invisible until they are upon you. At first, you think your eyes are playing tricks on you when you find yourself squinting, barely making out gray forms moving around in the “five-foot-safe-distance-tohumans” distance. It soon becomes really important to mentally define the motion of the beast to level your fight or flight reaction. Dolphin or shark? Even so, the sharks really aren’t interested in us, but more so curious. To date, however, the most memorable chatter back onboard was the night when we had two, 600-lb., full-grown sailfish come in fast and furious on two of our buddies, who had to lock arms back-to-back in order to get back to the boat and fend off their stabbing swords. Note to self: A) Glad it wasn’t me, and B) sailfish are massive and very aggressive hunters. Silky sharks are also not shy and will zip in and hit you, repeatedly, trying to raise a response out of you. I’ve been told to turn off my lights when this happens, but honestly, I need to see where they are. Hanging still in the blackness is just a tad too creepy even for me, although I have done it. Words of wisdom, never, ever wear white at night. It looks like fish chunks to them and is much like ringing the dinner bell, especially after a brigade of squid have just come through nipping off the tasty parts and leaving a rain of fish guts, which, in-turn, only attracts yet another layer of predators. Alas, we do whatever it takes to get the photo.

Used with permission from the Data Science Bowl® and Booz Allen Hamilton®

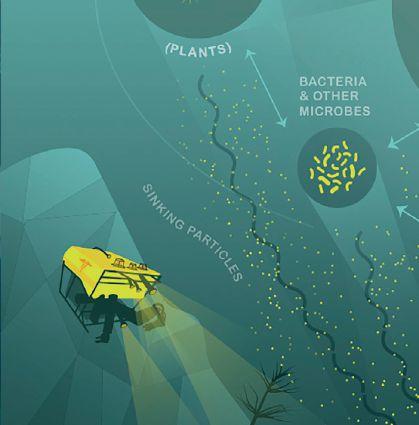

OXYGEN CYCLE OF LIFE FROM OUR OCEANS

When carbon emissions are released into the air, they literally rain down, run off into land and the oceans. This is the simple explanation of what contributes to ocean acidification and warming of oceans. Phytoplankton—one-celled animals—are the main source of food for plankton and the major component of the marine diet that, in turn, becomes food up the chain of life. In addition to starting off this bigger creature eats little creature phenomenon, phytoplankton’s most precious function is that it also consumes carbon dioxide and uses CO2 and sunlight to photosynthesize with the by-product being oxygen. However, when unnaturally high amounts of CO2 is absorbed into their shells—this imbalance caused by ocean acidification—it disrupts their ability to grow properly, causing a thinning of the shells and lowering their ability to produce oxygen at the same levels as in the past and causing them to die sooner. So, if you ever questioned the value of phytoplankton (or ever even thought about it), just remember that they are eaten by herbivorous marine creatures and, in turn, carnivores eat the herbivores and it goes all the way up the line of sea life to tuna, billfish, whales, and sharks. Therefore, these little guys are crucial to the balance of nature above and below the horizon line as food and oxygen.

It is up to us all to dig deeper than the surface issues of plastic bags in the bellies of marine life. We need to pay direct attention of Earth’s source of oxygen and on how to keep our planet as healthy as possible. For the health of us all.