49 minute read

Marlin Mayhem

Marlin Mayhem Marlin Mayhem

BY GHM STAFF Alabama’s newest billfsh tournament turns into a record-setting weekend.

Known for incredible fshing, the northern Gulf of Mexico’s reputation for billfsh action was cemented this past summer when a new tournament produced multiple record-setting fsh and gave Gulf Coast anglers a show they won’t soon forget.

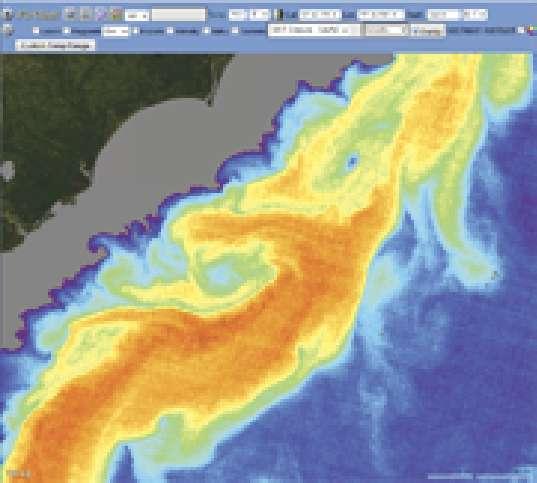

In just its second year, the Blue Marlin Grand Championship at The Wharf in Orange Beach, Alabama, produced three blues that were all north of 700 lbs., and the top two fsh, weighed within hours of each other, both broke the 24-year-old Alabama state record of 779 lbs.

The action started early. On the frst night, fve marlin that were caught all met the tournament’s 101” minimum length. Those are big numbers for the Northern Gulf. First to the dock was the Whoo Dat. Angelo Depaola’s 105.5” blue marlin weighed 426.2 lbs., and would have won the previous weekend’s tournament in nearby Pensacola. It would end up being the “smallest” blue registered.

In all, teams in the 50-boat tournament were competing for more than $1 million in cash prizes and the drama was intense. In late evening of the inaugural tournament day, the crew of the Rising Sons brought in their frst fsh—a stunning blue marlin. The Louisiana-based boat was fshing about 130 miles to the southwest from Orange Beach when their marlin hit and put up a two-hour fght. Angler Jeremy Powers worked the rod and the crew had to dump the leader twice before getting the fsh aboard. As the big blue was hoisted, the announcement was made, “The new Alabama state record…789.8 lbs.!”

A crowd of about 5,000 cheered as the crew celebrated in a shower of beer suds. Another blue weighed in at 452 lbs. and then word came of the night’s fnal fsh. The Reel Fire was headed to the dock with a fsh measuring over 120”. Everyone knew that the new state record might not be enough to win the day.

When Reel Fire arrived, the dock crew strained to

Weigh-in was a magical time at the Blue Marlin Grand Championship this summer in Orange Beach, Alabama. The tournament saw the state record for blue marlin broken twice in one night. Photo: Mark Worden.

H i - - I ’m Mark Nichols, fishing finatic first, and owner of DOA Lures second. I design lures because of my love of fishing...cer tainly not to get rich. My inspirations for designs come from time on the water, not time in the office. I could be (monetarily) wealthier by hanging out at DOA World Headquar ters, copying other manufacturers’ products and sending my designs outside the U.S. to be produced; however, that would just not be me--

I define wealth by how happy I am. I consider myself ver y wealthy. Also, I hire Americans to supply my materials and to produce my lures and apparel. I choose to do this for my peace of mind and for my family...those at home and those at work. Fishing is therapy. Go get some today.

w w w. d o a l u r e s . c o m To l l - Fr e e 1 - 8 7 7 - 3 6 2 - 5 8 7 3

Funding Knowledge

Guy Harvey scholarships support a record eight student researchers in 2013–14.

BY DOROTHY ZIMMERMAN

A record eight graduate students at universities in Florida have received Guy Harvey scholarships to study fsheries science and policy in the marine waters of Florida and the Bahamas. The research of these aspiring marine scientists will help advance what we know about such important species as tarpon, grouper, snapper, king mackerel, sharks and the invasive lionfsh.

The new fellows were selected from the largest-ever pool of scholarship applicants—52 in all—and will receive $5,000 scholarships to support their respective academic projects.

Among this year’s winners is Bob Ellis at Florida State, who became fascinated with what he calls the “prairie dogs” of Florida Bay, red grouper, one of the state’s most commercially important species. Red grouper burrow in and clean out solution holes—small versions of sinkholes— on the bay foor and, in turn, create habitat for a broad community of other important characters like snapper and the spiny lobster. Ellis’s research attempts to unravel numerous questions that Bob Ellis resource managers have about how these excavations infuence marine ecosystems Alexis Segal across the Gulf of Mexico, particularly when they depend on species that are so valuable to commercial and recreational fshermen.

In addition to species-specifc research, some scholarships fund other areas of conservation work. In a frst-ofits-kind, one of this year’s awards will be split by a team of two law students from the University of Florida who are responding to inquiries from the Bahamian government, Ocean Crest Alliance and other partners to explore the creation of a marine managed area of Long Island, Bahamas. Alexis Segal and Caitlin Pomerance will use their Guy Harvey award to travel to Long Island to lead the community meetings to collect and analyze the needs and wants of local residents, particularly the subsistence fshermen, to better manage and protect Long Island’s vital fsheries.

The remaining Guy Harvey scholars for 2013–14 are:

Amber Ferguson—investigating prey capture biomechanics, anatomy and bite force in the king mackerel, one of the most sought-after recreational fsh.

Johanna Imhof

Johanna Imhof—studying the potential mercury contamination of deep sea sharks in the northern Gulf of Mexico following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Kristin Kopperud—building new knowledge about the fundamental properties of visual systems in fsh, which may one day yield important practical applications for human health, as well as the conservation of tarpon, bonefsh and sharks.

Tyler Sloan—examining how water temperature may afect the feeding performance and behavior of diferent life stages of the invasive lionfsh.

Arianne Leary—investigating the long-term efects from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and its efects on valuable Gulf of Mexico fsh species, such as small sharks and red snapper.

Since the Guy Harvey Ocean Foundation and Florida Sea Grant created the scholarship program in 2010, $84,000 in scholarships has been given to 19 students at Florida universities. A panel of faculty members selects winners, and this year’s winning students come from Florida State University, the University of South Florida, Florida Institute of Technology, the University of North Florida and the University of Florida.

Kristin Kopperud Arianne Leary

S.C. Lottery Tickets Land a Conservation Jackpot

BY JEFF DENNIS GHM INSIDER

Earlier this year, Dr. Guy Harvey followed up on the success of his Florida lottery tickets by loaning his signature artwork to the South Carolina Education Lottery. The result was a big win for conservation. A limited time scratch-of ticket for $5 a play helped to generate a whopping $226,000 for conservation projects in the Palmetto State.

As part of the program, Dr. Harvey traveled to the South Carolina Aquarium in Charleston on October 5, 2013, and awarded a $75,000 donation toward a new touch tank exhibit for sharks. Set for completion in the spring of 2014, the shark exhibit will help educate the public on how the ocean’s top-tier predators are also in need of conservation eforts.

“Sharks are becoming less perceived as predators, and the touch tank will help to reinforce that,” said Harvey. Another step citizens can take is to join the new Hammerhead Nation found on www.GuyHarvey.com, where marine conservation is a cornerstone.

Other recipients of the Guy Harvey lottery funds include the

AD

Left: Guy Harvey scratch-of tickets paid of big in South Carolina in 2013. The program raised almost a quarter-million dollars for conservation, including a $75,000 grant to the South Carolina Aquarium. Photo: Jef Dennis.

Coastal Conservation Association of South Carolina, the Harry Hampton Fun and the Dolphinfsh Research Program.

“There is no greater gamefsh than the dolphin,” said Harvey. “Mahi entertain anglers when they jump and fght. And from an artistic point of view, they look amazing and are a pleasure to paint.”

Scott Whitaker is the CCA executive director in South Carolina, and is their longest-tenured state director in the nation. Upon receipt of $75,000 in funds from the Guy Harvey Lottery game, CCA’s work on behalf of fsh habitat will continue.

“Oyster restoration projects up and down the coast are set to expand thanks to this funding,” said Whitaker. “In general, this money helps us be on solid ground heading into our 2014 conservation calendar, and we are very grateful.”

South Carolinians embrace their coastal heritage when it comes to loggerhead sea turtles or to nesting shore birds like the oystercatcher. Recreational anglers and shrimpers are coming to realize that the bounty of seafood served up by the estuary is by no means limitless. The conservation groups that Guy Harvey supports with lottery funds will help future generations of saltwater enthusiasts guard the sustainability of the ocean.

AD

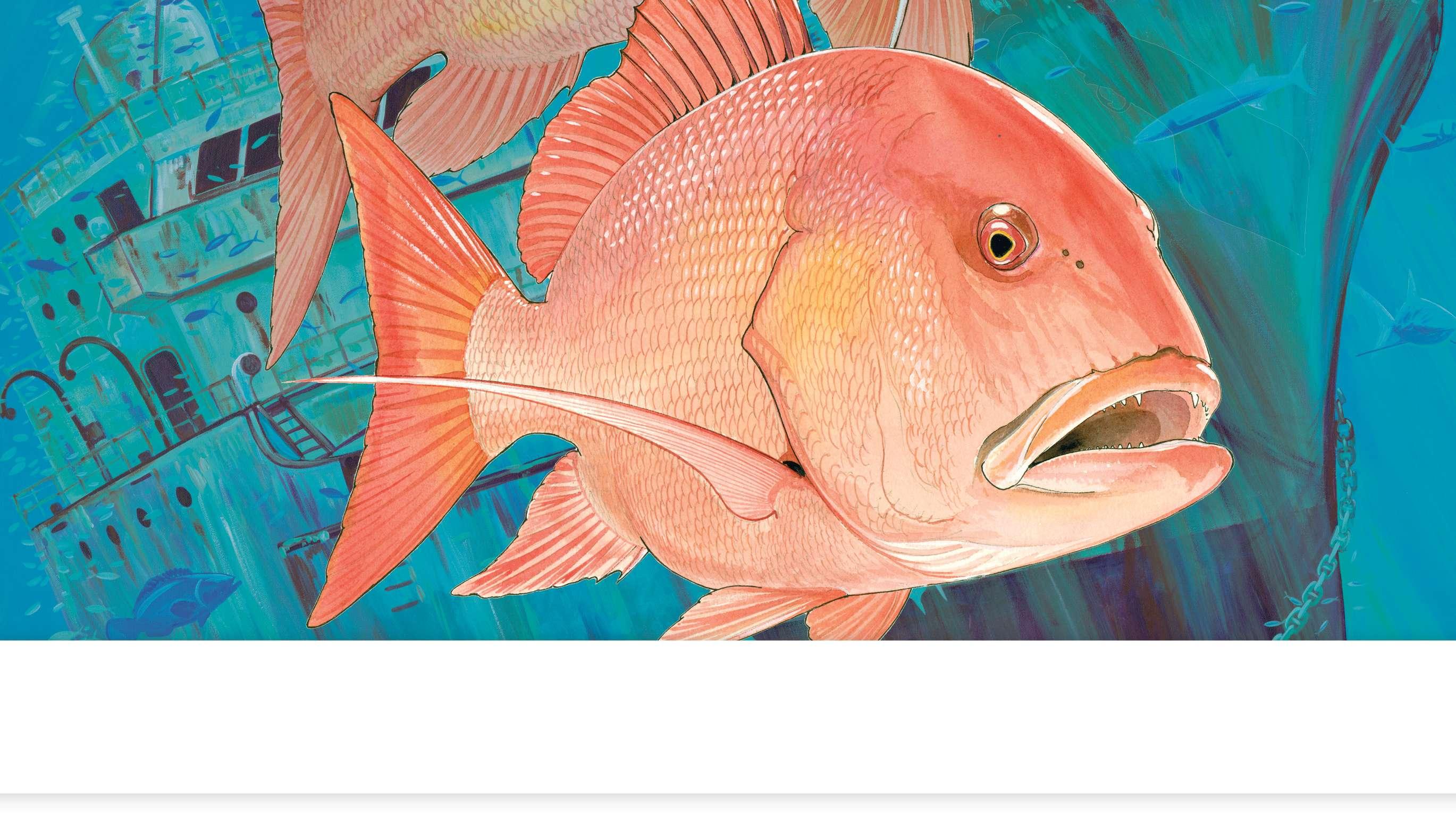

In the U.S., the artifcial reef boom ramped up after 1984, when Congress passed the National Fishing Enhancement Act, which encouraged states to construct artifcial reefs. Since then, the reef rush has continued to accelerate. In the early days of American-based artifcial reefs, myriad scientifc studies were done, which asked one simple question: do reefs create more fsh or do they simply aggregate the fsh that were already swimming around looking for a place to settle down? While there is still some debate, the overwhelming evidence is that artifcial reefs provide habitat for fsh populations to fourish. Along the northern Gulf of Mexico coast, this is especially true for gamefsh species such as snapper, grouper, triggerfsh and others that are perfectly suited to underwater structure. Consider the red snapper. Its population in the northern Gulf continues to grow faster than Taylor Swift’s bank account.

In the 1980s, I did a lot of scuba diving in the Gulf. We kept a 22-ft. boat in Orange Beach, Alabama, and had a list of several hundred public and private reefs we’d hit within 15 miles of shore. I still have the list and like to look at the notes next to certain numbers like, “20-lb. grouper!” or “Big shark!” or “No big fsh—try next summer.” We spearfshed like wild

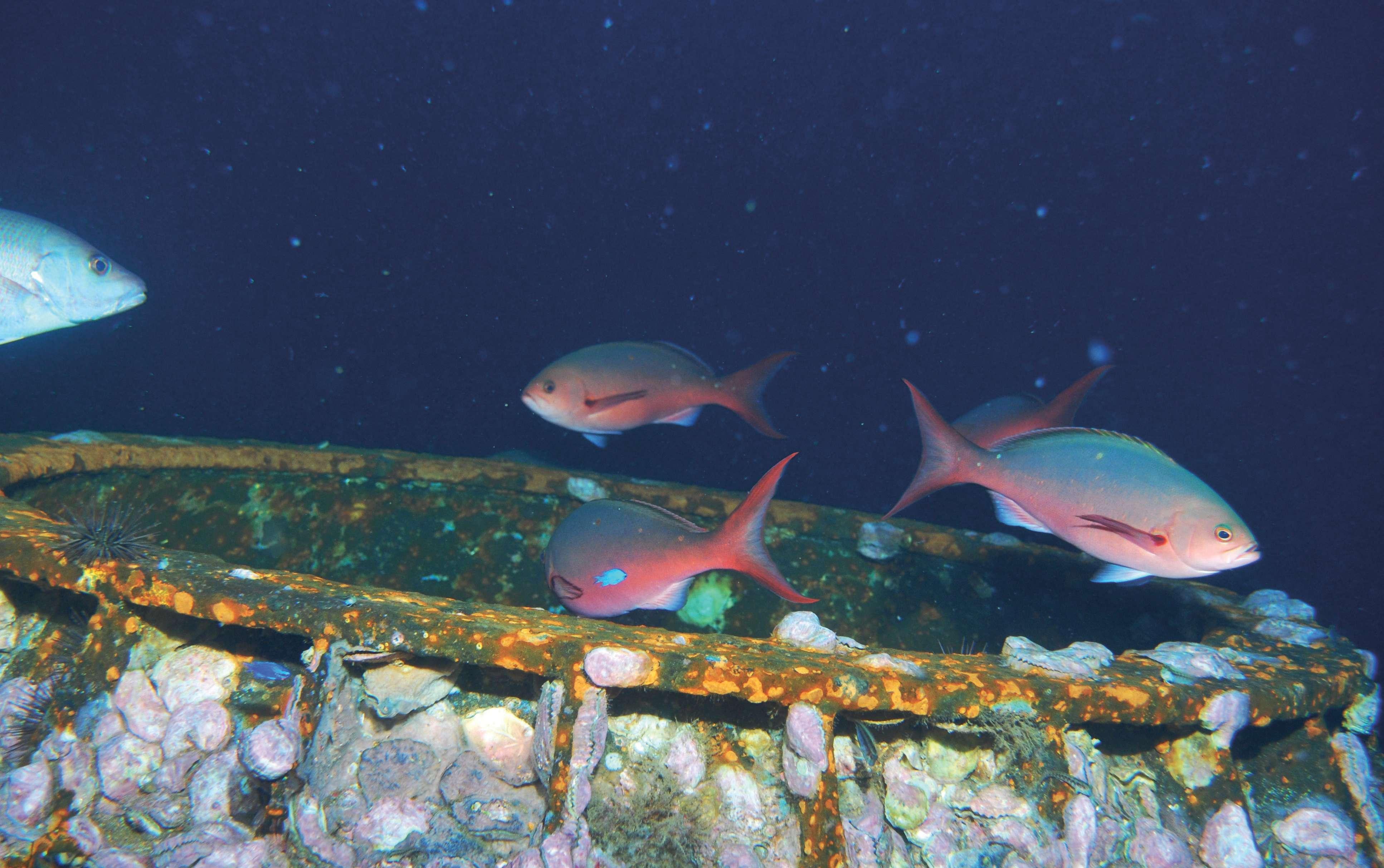

Baitfsh swim around a pyramid reef in the Gulf. Photo: Walter Marine.

Scrap car bodies were some of the frst artifcial reefs. Here, a group is stacked on a barge, ready to slide of into the water. Photo: Walter Marine.

Opposite: The “Reefmaker” of Walter Marine deploys pyramid-shaped artifcial reefs into the Gulf of Mexico. These reefs have Florida limestone embedded in them to mimic natural reef habitat. Photo: Walter Marine. Right: Bridge rubble has been widely used to build reefs of Alabama. Divers dubbed this site “Little Rome” because large, vertical columns are a reminder of ancient ruins. Photo: Lila Harris, Aquatic Soul Photography.

men and always brought back a load of amberjack, snapper, grouper, triggerfsh and the occasional lobster. Back then, Alabama was on a mission to build the nation’s most extensive network of reefs. They dropped Army tanks, tugboats, ships, school buses, hundreds of cars and just about anything that would make a good home for a fsh. Of course, anything with hydrocarbons, like gas tanks, brake lines and so forth, were removed before they were dropped into the deep. Then, in 1989, a new bridge was built at Alabama’s Perdido Pass and the old bridge was tagged to become a reef extravaganza. (As a side note, we made a night dive under the old Perdido Pass bridge a few weeks before it was removed and were freaked out to see that many of the massive cement pilings had been eroded so much that we could swim underneath them. Car and truck trafc moved along above us unaware that only a few rods of rebar seemed to be holding the bridge up.)

Fortunately, the bridge was deconstructed before it collapsed. Also, Alabama had the wisdom and foresight to remove the bridge in giant chunks to make some humongous reefs. Today, almost 25 years later, those reefs are still extremely productive and are part of more than 17,000 man-made reefs of of Alabama’s coast. Even though the state has about 60 miles of Gulf-front coastline, it has more artifcial reefs than any other state in the union, including Florida.

One of our favorites sites to dive was a place we named Little Rome (it still exists) because the old concrete bridge pilings I’d once swam under were dropped into the sandy bottom in 90-ft. water in such a way that the rebar stuck into the sand. This allowed the 60-ft.-long pilings to stand erect even though they were tilted and cracked with big chunks scattered along the ground like the ancient ruins of Rome. Since most dive sites in the Gulf only have a relief of 10 to 20 feet, it was nice to be able to ascend up those pilings to within sight of the surface. Plus, they held a lot of nice fsh.

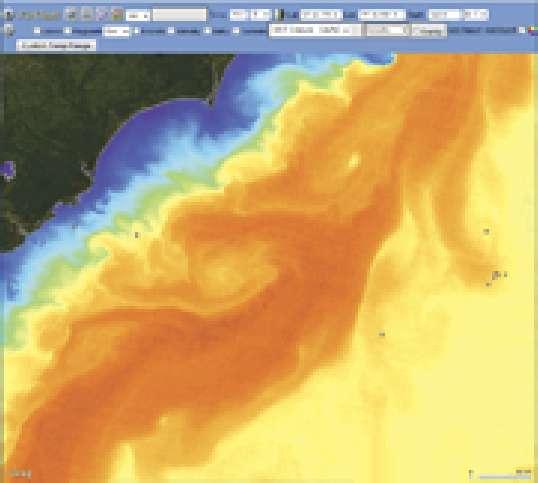

Fishing Alabama’s reef system is pretty simple. All you need is a decent boat with a GPS and a depth sounder. You zip ofshore to the latitude and longitude intersection, and then you slowly circle the area until you see a big red and yellow hump on your bottom machine. Then you fsh. Experienced captains can decipher the colors and shapes and pretty much tell you whether a fshing spot will produce good fsh and what kind of fsh to expect. Even a beginning boater just learning how to punch numbers into his GPS and set the gain on the depth sounder can have a lot of success…if the spot has fsh. Some well known reefs can get fshed out during the peak fshing season, but there are so many reefs it’s just a matter of moving to the next one until you fnd the fsh.

Scuba diving these reefs is a completely diferent animal. Descending in 60 to 100 feet of water can be eerie, like falling through outer space, because you can’t see the sandy bottom or the reef when visibility is 25 to 50 feet. Occasionally, the blue gulfstream water moves in and visibility might jump to more than 100 feet, but, for the most part, as the diver is pulling down the anchor line, he’s staring into a blue-green void, hoping and praying that some structure will appear.

It takes a skillful captain to hook the anchor within 50 feet of the reef. Currents and wind move the boat as the anchor is falling. Then an anchor will drag before it catches. On more dives than I like to admit we got to the sandy bottom and all we could see was more sand in all directions. We call that a moon walk because without an artifcial reef to explore, the bottom of the Gulf is one big, fshless moonscape.

While Alabama is the nation’s undisputed champion of man-made reefs, the

Just one day after its sinking, the LuLu was already attracting fsh, including this nicely-sized red snapper. Left from top: Artifcial reefs support fsh of every size—from behemoth goliath grouper (top) to vermillion snapper (locally called mingo or beeliners; middle) to bait fsh (opposite). Photos: Lila Harris, Aquatic Soul Photography.

David Walter Reef Maker

If they gave out world records for building artifcial reefs (and by golly they should), the winner, by a long margin would be Alabama seafarer David Walter. Over the course of three decades, Walter and his company, Walter’s Marine/Reefmaker, has put down more than 35,000 artifcial reefs.

“Back in 1984, when the oil business had crashed, I bought an old 42-ft. work boat for $2500,” Walter recalls. “I wasn’t sure what to do with it and a captain friend of mine, Earl Grifths, told me I should haul old cars out and make reefs out of them.”

Walter was skeptical.

“It sounded like a crazy idea. I didn’t think anybody would pay me to haul old cars out there. But I told Earl that I’d convert the boat if he could get me 20 cars and pay me $100 per car to dump them. The next day Earl called and he had 40 cars.”

And so began Reefmakers long career of building reefs along the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic coasts. It became so popular for fshermen to have their own private car or school bus reef that Walter’s business took of like a king mackerel hitting a spinning rod.

“At one point, I had a year-and-a-half waiting list,” Walter said. “We just couldn’t build them fast enough.”

Over the years, cars went out of vogue and reef making materials morphed into more durable and permanent structures.

“In the early days, we experimented with diferent designs until we settled on a structure with limestone rocks. Our customers expected to catch a lot of fsh from each reef, so we made the largest artifcial reef in the US.”

These days, Walter is still hired by sport fshermen, but his primary clients are governments. “We’re building a lot of snorkeling reefs for cities and counties. We put 40 structures of of Pensacola Beach and now they want more. The fshermen, divers and snorkelers love them.”

Walter’s company was the obvious choice to put down the Lulu. It was their 13th ship to deploy.

Red snapper is the poster-child for bottom fshing in the northern Gulf, and records indicate average catch size has more than doubled in just 10 years. Photo: Walter Marine.

In September of this year, the Monterrey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch folks, who have as much infuence over seafood consumption as Miley Cyrus does over questionable dance moves, recognized this positive trend in the fshery. They upgraded the rating of Gulf red snapper from “Avoid” (meaning, if you eat this, you’re a horrible person) to “Good Alternative.” People of conscience can now order Gulf of Mexico red snapper at a restaurant or buy it from a seafood market without incurring the stigma normally reserved for those who club baby fur seals. For the fshing industry, and for everyone who buys seafood in a restaurant or store, this is wonderful news.

But the commercial red snapper catch and the recreational snapper catch are as diferent as Jay-Z and Tim McGraw. Commercial guys operate on what’s called an IFQ, or Individual Fishing Quota. That means they are allotted a certain number of pounds of fsh to be caught during the year. Essentially, they can catch it whenever and however they like. This system carries many benefts. Commercial guys can fsh all year, make money all year, and decide to stay home and be safe when the Gulf looks like a washing machine set to “agitate.” There’s always tomorrow.

Commercial boats also have very strict reporting regulations. They turn in catch numbers on a near daily basis, so it’s easy for government types to keep track of how many fsh are being harvested, their relative size and the areas where they are caught. All this makes tracking and managing the commercial red snapper fshery fairly straightforward.

That’s the good news. The bad news is that recreational fshing management is a bit of a joke with a bad punch line. Many would even say it’s an insult to the word “management.” Rather than operating from an IFQ, the recreational sector is allotted a Dr. Bob Shipp—Gulf snapper guru. certain number of pounds of red snapper each year that must be caught during a limited season. In recent years, that meant one month of fshing for red snapper and a two-fsh per day bag limit. Seems straightforward enough until you try to track thousands of recreational fshermen and what they caught. Catch totals are collected by doing phone surveys, posting people (“monitors”) at the docks to conduct interviews with fshermen and other equally inadequate methods. This limited data is then plugged into some very complex mathematical models that also weigh a whole range of other factors (more on that in a minute) and the result is how many pounds of fsh have been harvested in a given recreational season.

“Last year, a huge glitch was discovered,” says Dr. Robert Shipp, former chair of the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council, the governing body responsible for managing red snapper. “In past years, the monitors at the docks

Snapper season drives ofshore fshing in Orange Beach, Alabama and many other Gulf Coast ports. A typical summer weekend can see thousands of boaters on the water. Photo: Orange Beach, Alabama, www.OrangeBeach.ws.

were knocking of at 3pm. But the catch limit faster and faster each year. This is further exacerbated by the fact that a new data collection system the catch limit is counted in pounds and average fsh size has doubled, so catching approved by Congress now has the limit automatically means catching fewer fsh. The result of all of this is that monitors staying later in the following the old rules requires shortening the fshing season so the catch limit is day. When they stayed until 5 not exceeded. or 5:30, landings skyrocketed.” Now, with the revelation that the last 10 to 15 years of numbers are The result, says Shipp, is completely unreliable because of poor data collection methods (monitors leaving Tom Steber—President that data from previous years is the docks at 3pm instead of staying until later in the day), it means the stock Orange Beach Fishing Association. now wildly in doubt. “They don’t assessment process has to start from scratch. And even though it seems quite know what to do with the last 10 obvious to everyone involved—even the pelicans on the docks—that snapper to 15 years of data because they know it’s all wrong. When they came in with these numbers are growing, there’s no way to scientifcally justify an increase in catch numbers, it meant that the quota for that year had already been exceeded.” limits because it can’t be backed up with hard numbers.

This new revelation is likely to compound the problems of the current trend This trend seems unbelievable to most anglers, and the reality of more fsh in recreational management. As red snapper numbers have been increasing, but less fshing is hard on everyone, yet what’s at stake is far more than just a nice season length and bag limits have been shortening. This is counter-intuitive, and recreational activity enjoyed by a few fshermen. There is a huge economic impact maddeningly frustrating to fshermen. Essentially, because people are obeying the as well. rules and the stock is doing well, as a reward, we all get to fsh less. But the problem “We ran 200 trips out of here last weekend,” says Tom Steber, manager of comes from the fact that it takes a long time (about three years) for researchers Zeke’s Marina in Orange Beach, Alabama. “That’s more than all the trips we ran for to conduct a full-blown stock assessment—a necessary step before increasing the last two months.” fshing limits. So, while new research is being conducted, the old rules must still be Zeke’s is home to a good portion of the Orange Beach charter feet, which enforced. Meanwhile, since snapper numbers are going up, fshermen are reaching is the largest such feet on the Gulf Coast. I visited with Tom in mid-October, just

Just in from a day on the charter boats, this group of anglers shows of some big red snapper, grouper and a mixed bag of other fsh—a typical haul when snapper season is open. Photo: Orange Beach, Alabama, www.OrangeBeach.ws.

after a special, two-week snapper season closed. He was happy for the boon in business, but he also made it clear that charter fshing in the 10-plus months that don’t host a snapper season is a far cry from what it used to be.

“Our captains have really had to adapt,” says Steber, who is also the president of the local charter association. “Where we have lost business is from the corporate sector…from companies coming from Mobile or Birmingham and treating their employees or clients to some time on the water. Instead, now, we cater much more to a family experience, where people are not fshing to fll up coolers, but fshing purely for fun. We’re also fshing more for other species like dolphin and king.”

The other point that Steber makes is that cramming the majority of snapper fshing into one, 28-day season in July is a real killer for getting the most out of the region’s tourism business during the rest of the year. The Gulf Coast, especially the section from Gulf Shores to Orange Beach, Alabama, is a Mecca for visitors from all over the Southeast. And, when the weather is good, fshing is popular the majority of the year. If snapper season was open during Memorial Day, Labor Day, Thanksgiving—not to mention during other local events such as the annual Shrimp Festival and multiple music festivals—charter boats could be full and running virtually all the time. A short snapper season both reduces the overall tourist draw and it keeps businesses from maximizing their profts when tourists are present. The bottom line is that snapper season is a huge economic driver. It is directly related to occupancy rates at hotels, to receipt totals in restaurants and to gas sales at service stations—all the things that are part of a normal tourist economy.

The Red Tide of History

For local fshermen, snapper fshing is equally important. In fact, it’s a deeply ingrained part of the culture, especially in Southern Alabama and along the Florida Panhandle. People here never talk about “deep sea fshing.” Sure, those words are on a few billboards targeting tourists, but that’s not what the locals do. Here, people go “snapper fshing,” as in, “I went snapper fshing and caught a nice grouper.”

And it’s been this way for about 150 years. Pensacola, stuck out on the western end of the Florida Panhandle, is a city that used to be known as the red snapper capital of the world. And they meant it. Because of the snapper fshery, there was a time when Pensacola’s port was the busiest in the nation, even more so than New York.

When you examine the power brokers who dominated Florida’s Panhandle in the early 1900s, the leading role goes to a Mr. R. Snapper. His supporting cast was a group of entrepreneurial humans who capitalized on the legions of red snapper that were landing in Pensacola, as well as in nearby Mobile and New Orleans. If you review history books of the region, two men you’ll run across frequently are

The exact date is unknown, but this 19th century photo shows fshermen taking their catch of red snapper into Mobile, Alabama. Photo: USA Archives.

movers and shakers E.E. Saunders and Andrew Warren. These two fellows are described in historical records as “very thoughtful and skillful businessmen, as well as imaginative marketers.” Translation: they were the rich guys in town—the “Big Fish,” if you will pardon the pun.

Saunders and Warren promoted snapper, as well as grouper, in cans before StarKist ever packed its frst tuna in a tin. Warren even published a special cookbook to prepare fsh from “The Red Snapper Capital of the World.” Back then, the Gulf was a wild west of sorts and the fsh came in like fruit falling from a tree. This period of snapper prolifcness (though that’s not even a real word) is a fascinating history. It’s also relevant to today’s fsherman, because it still infuences how we manage snapper fshing.

They used huge sailing “smacks,” some of which were up to 200 ft. long, to go out for a month or more and return with their live wells full of red snapper. Some say the ships were called "smacks" because of the sounds of water sloshing around in their live wells. Using this method, ships would go out and fsh and bring in up to 6,000 lbs. of snapper at a time. This fgure tripled later on with the availability of ice, allowing ships to chill their catch down while still at sea. Commercial landings peaked at the turn of the 20th century, with more than 6 million pounds of tasty red snap-daddy’s coming in through Gulf of Mexico ports.

It was a grand time, but red snapper were being fshed hard. Even as early as 1887, we have historical documentation of smacks moving out of the northern Gulf and sailing as far south at Campeche Bay, of the western coast of Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula. By 1910, a majority of the commercial fshing feet was traveling to Mexican waters to fnd red snapper. In fact, by 1955, it was well documented that 75% of the snapper coming into Pensacola and 50% of the snapper coming into other Florida west coast ports, were all from Mexico’s Campeche fshing grounds.

This history lesson is important because those historical catch fgures have helped skew present management practices. Management goals—how many fsh we think there should be so we can maximize the resource while still sustaining the population—are based on a number of diferent factors. These include, among other things, historical catch data, the biology of the fsh and its ability to reproduce, and on achieving a healthy age structure in the population—having a certain percentage of young fsh, adolescent fsh and mature adults, etc. But the underlying premise of tracking historical catches assumes you’re still managing the same habitat. Yet today’s snapper regulations do not cover Mexican waters, just the 200-mile exclusive economic zone that extends from the U.S. coastline. So just like having bad catch data, having skewed historical records has contributed to the debacle that we call “red snapper management.”

Habitat Sweet Habitat

Our history lesson is not quite fnished. In the 1940s, the Gulf of Mexico

began to change in a big way with the beginning of gas and oil exploration. This started, of course, in the western Gulf, namely of of Texas and Louisiana. Today, tens of thousands of active and retired oil rigs dot the underwater landscape in the Gulf. Fishermen know these structures as serious fsh habitat—most of them packed tighter than a senior living center in Palm Springs. In areas that used to be relatively barren expanses of sand bottom, rigs support healthy populations of creatures from every level of the underwater food chain.

“You can’t underestimate the sea change in habitat that came in the 1940s with the introduction of oil drilling,” says Dr. Shipp, who has spent three decades studying Gulf reef fsh and is a past chairman of the Department of Marine Science at the University of South Alabama. In a research paper published in 2009, Dr. Shipp documented the growth in red snapper catch totals in the western Gulf from an annual average of less than a million pounds through the frst half of the century to about 4 million pounds in the year 2000. Peak catches came in the late 1970s at almost 6 million pounds. Dr. Shipp attributes this sustained growth to habitat increase.

“One of the problems we have today is that our current models don’t account for this massive increase in artifcial habitat,” says Shipp. He and others have been petitioning the Gulf Fishery Management Council to do just that. Research has established that habitat creation does not just “collect” fsh and concentrate them at one site, but it actually allows for a larger population of fsh.

This is signifcant not just for Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi, but for Alabama and Florida as well. Although it has the smallest section of Gulf of Mexico coastline, Alabama has the region’s most prolifc artifcial reef program. In addition to some oil and gas structures, partnerships between fshermen, the state and outside organizations have created a 1,200-sq.-mi. reef zone with more than 17,000 reefs. These structures include everything from scuttled ships to concrete “reef balls” and discarded bridge rubble. Shipp and his teams have regularly conducted fsh surveys, including video surveys, on select structures of Alabama coastlines. He has also conducted sonar sweeps to document the number of artifcial structures still in place after years under the surface. His fndings have backed up what fshermen on the water have been saying for a long time…the snapper are everywhere. In fact, Shipp believes that recreational red snapper fshing could go from one month to six months with a two-fsh limit. He says if that kind of fshing was allowed, and limited to waters above 20 fathoms (120 feet), there would be little danger of hurting snapper stocks over a three-year period. That idea is part of a “straw man” proposal he is publicizing to help kick-start a discussion on a new overall approach to snapper management.

Ready to Fight

Bad data, an inefcient system of limited seasons, a skewed historical precedent and a fawed view of the Gulf ’s fsh habitat are all taking their toll on snapper management. Added to this are human nature and the naturally slow moving wheels of government bureaucracy. But angst and anger among all

parties has brought about some change. snapper fshing between recreational and commercial groups. Currently, the split

At the time of this writing, multiple bills and proposals are being kicked is nearly even. But recreational and charter fshermen, along with their allies, are around, both in Congress and in the various legislatures of the states along the seeking a greater piece of the pie. Their argument is that current allocations are Gulf. There is a growing push to see control of the red snapper fshery taken away based on skewed catch data from the 1980s, and if a new allotment were made from the National Marine Fisheries Service and given to the states to manage on present data, recreational guys would get a bigger share of the limited red however they see ft. In 2014, a partial move along these lines is already set to take snapper quota. place. Each state will be allowed to manage its share of the yearly snapper quota, Understandably, this move does not have commercial fshermen very excited. though the quota itself will still be determined by the National Marine Fisheries They are making money. Snapper sells for a good price, and with the recent Service. For many, this is a move in the change in recognition from the seafood industry of right direction, but still does not go far …Shipp believes that the health of red snapper stocks, demand should enough. Captain Steber, in Orange Beach, continue to rise. If their current quota is cut, without believes that the states need full control recreational red snapper fishing limits being raised, they are going to feel a real if recreational fshing, as we know it, is to could go from one month to six economic crunch. They are also warning, through survive along the Gulf. a new marketing campaign called “Share the Gulf ”

“I am hopeful that something good months with a two-fish limit… (www.sharethegulf.org), that such a move could can happen. Honestly, I think that the limit access to red snapper in seafood markets and recreational fshing groups, such as CCA and others, will have to come together restaurants around the country. Many also have concerns that at the state level and sue the Feds for control. I think everybody fnally feels pushed back in a there is not the expertise or manpower to efectively manage commercial fshing. corner enough to fght.” Some experts, like Dr. Shipp, have suggested leaving commercial fshing under

To thicken the plot, there’s also a move among recreational fshermen to bring Federal management and just moving recreational fshing to state control, although more immediate change. U.S. Senator David Vitter, from Louisiana, has proposed no one can agree what that control should look like. The one thing everyone does legislation that would force the NMFS to reexamine the current split of red know is that change is coming. For most, it can’t come fast enough.

Fueling Alabama’s coastal fshing is a wonderful confuence of geography, good water and an entire generation of conservation-minded anglers. Mobile Bay covers 400 sq. mi., and with the fve major rivers that feed into it, helps create the fourth largest estuary in the country. It sustains the base of a massive aquatic food chain, with the brackish waters and marshes of the bay providing a home for shrimp, crabs, mussels and baitfsh. It also serves as a nursery for a wide range of recreationally important species and is home to big redfsh and healthy populations of founder, speckled trout and white trout. A series of oyster reefs, deployed years ago by the state, are still maintained and create fsh habitat in the bay and compliment the natural drop-ofs, grass beds and channels that fshermen frequent with great success.

These rich inland waters are matched ofshore by more than 17,000 artifcial structures put down in a 1,200-sq.-mi. designated reef zone. It is, by far, the largest collection of artifcial reefs anywhere along the Gulf and does not even include structure provided by the state’s oil and gas industry. The reef zone is also a great example of how fshermen in the state have really helped themselves.

For years, says Tom Steber, head of the OBFA, the charter boats docked at Zeke’s Marina (one of the busiest in Orange Beach) were required to put down between fve and 10 reefs every year.

“We knew that building habitat would build the fshery,” says Steber. “So it was incredibly important.”

And, of course, things have not slowed down. In addition to the sinking of the LuLu, a 271-ft. freighter last year, Steber says there are plans to sink two more ships over the next three years.

Beyond the reef zone, Alabama’s coast is well within shot of some great

Multi-passenger boats are great for large groups, and experienced captains know how to deliver fshing action. The 65-ft. Emerald Spirit is certifed for up to 50 passengers and ofers bottom fshing, trolling, overnight trips and tournament fshing. Photo: Orange Beach, Alabama, www.OrangeBeach.ws.

Left: With more than 17,000 artifcial reefs in the area, fshing opportunities abound and captains can tailor trips to fsh for specifc species, whether bottom fshing or trolling. Photo: Gulf Coast Convention and Visitors Bureau.

deepwater formations. The “Nipple,” a drop-of along the Gulf’s continental shelf, is a hot spot for serious blue-water action. Last year, the 24-year-old state record for blue marlin was broken twice in one weekend with fsh of 789 and 846 lbs. Tuna, white marlin, blue marlin and sailfsh are all on the menu for those who venture ofshore.

Bringing your own boat to the region is easy enough, and many anglers love the challenge and opportunities that it provides. But for many visitors, booking a charter trip is the smartest way to hook up. Anglers can also tailor their trip. Looking to take home a cooler full of meat? Get some buddies together and schedule a six-pack during the summer snapper season. Want to hone your fyfshing skills? There are veteran inshore guides who can both put you on the fsh and teach you how to fsh. Looking for blue water glory? Charter a boat and fsh one of the annual billfsh tournaments.

Charter boats have been running out of Orange Beach at least since the 1960s. Back then, the focus was more on trolling for Spanish mackerel and bluefsh rather than tapping an abundance of snapper. Still, the area earned a strong reputation for great fshing and good captains, and that has never changed. Today, the majority of charter boats are owner/operator businesses, many with deep roots in the area. And there is a strong conservation ethic that runs through the feet. “Hey, this is our water,” says Steber. “This is how we make a living. We all want to protect it and see it thrive.”

Personal investment, both in the area’s natural resources and in the sport, is typifed in captains like Alex Brewer. His company, Pleasure Island Charters, runs two boats: a 38-ft. Topaz, the Miss Carli, for ofshore fshing and a 22-ft. Sea Hunt, Game On, for inshore. The Miss Carli is named for Brewer’s daughter, tragically killed in an auto accident at the age of 17. The boat was purchased, reftted and named to honor a girl who loved to fsh with her family. For Brewer, there is a lot of pride in fshing.

“When I get repeat business, I know I’m doing my job,” he says. “We start putting people on sheepshead in late February, early March, and then we start chasing speckled trout and redfsh,” says Brewer. “We love having a good king mackerel run and, of course, red snapper season is always slammed. After that, grouper opens up.” For ofshore fshing, Brewer acknowledges that snapper season is the busiest time of year, but when snapper season closes, the fshing doesn’t stop…it’s just diferent. “We really diversify, going after triggerfsh, bee liners, amberjack. We’ve also been catching wahoo this year. It’s extra work to put out the high-speed trolling gear on our run out, but it pays of. You’re not going to catch anything with your tackle in the boat.”

Brewer also says that as much as he loves to catch fsh, his real passion is seeing someone else catch their frst fsh, especially kids. Family-oriented fshing is a big part of the business and it’s where they see the most return customers. It’s a trend attested to by other captains and points to the reality that fshing is a big draw for families visiting the area.

Of course, tourism drives the majority of charter boat fshing. Frank Ford, of Island Time Charters, runs inshore trips and says only 1–2% of his business comes from local anglers. The reason? Ford fgures that most have their own boat. Regardless, he understands what visitors are looking for, because until eight years ago, he used to be one.

A veteran freshwater angler and guide, Ford spent several years regularly coming down from his home upstate to fsh the area. He chartered boats until eventually buying a 23-ft. center console for fshing anytime he could. In 2000, he spent nearly three weeks fshing the rigs out of Dauphin Island and then discovered the backwater of Perdido Bay and Old River areas accessible from Orange Beach.

“I got tired of dragging my boat back and forth, and fnally bought a [house] down here,” says Ford. “We just fell in love with the place.” He and his wife opened Island Time Charters and started running inshore fshing trips. His specialty is guiding customers to big red fsh.

“They pull hard and put big grins on faces,” says Ford about his favorite species. “I like fall for both the bulls and the keepers. November and December have always been fabulous for the bull reds out of the beach. When we get a northern wind, you can catch them on a plug or bucktail jig. This time of the year, I’m all over the redfsh.”

The common denominator between Brewer, Ford and Orange Beach charter captains is a passion for fshing paired with a genuine enjoyment of helping others fnd success on the water. And since they fsh in a place with rich, natural resources, a healthy fshery and an unparalleled history of building reefs, that passion appears to have plenty of fuel for the future.

If you’re an old fart like me, you remember when the only limit on fshing was the size of your cooler. These days, catch and release, sustainability, and conservation have replaced catch it, clean it and freeze it. Although there may be less to eat in the fridge, there should be more fsh to catch in the sea. At least that’s the theory—a necessary sacrifce unless we want our children and grandchildren to consider chicken nuggets the fresh catch of the day.

The modern conservation movement is not new. It really sprouted in the late 1800s and early 1900s, led by the likes of our 26th president, Teddy Roosevelt, and Sierra Club founder John Muir, and articulated by author Henry David Thoreau, who wrote about man’s bond with nature in his classic book Walden. They spawned a new culture of thinking, but it caught on slowly in ocean management. Marine conservation was almost a foreign concept back then. Giant marlin, tuna and swordfsh were prolifc. Massive schools of salmon, mackerel and cod were easy pickings. Few believed that man could overfsh the vastness of the oceans. But we’ve learned over the centuries that Homo sapiens have an uncanny knack for decimating other species. Thankfully, we’re becoming almost equally as talented at restoring endangered animal populations—especially tasty ones that we love to hunt and eat.

Ironically, early marine conservation eforts were fostered by some of the very groups (such as commercial fshermen) who were pressuring the resource. Forward-thinking fshing companies realized they would be out of business quickly if they didn’t manage the fsheries that kept their doors open and provided fsh to restaurants, grocery stores and seafood shops.

“When my great grandfather, Frank Nelson, started Bon Secour Fisheries, he would have never imagined the degree to which oysters, shrimp or fsh are now regulated,” said Chris Nelson, who now runs the family business in the biscuits and gravy community of Bon Secour, Alabama, along with his brothers John and David. “Obviously, a lot has changed in the last 100 years.”

The Nellie Meta, the pride of Bon Secour Fisheries, opened in 1896 and, today, processes some fve million oysters a year. Photo: Bon Secour. Opposite: Oysters are the gems of Gulf seafood. Today, oysters are still gathered by using large tongs and working from small boats, the same basic method used for more than a century. Photos: ASMC.

John Andrew and John Ray Nelson.

DID YOU KNOW?

Most oyster afcionados partake in the slippery treat during months with an “R” in them— basically September through April. Cooler water creates a frmer, tastier oyster with less risk of bacteria that grow during the heat of summer.

Oyster shucking, still done by hand, requires the right tools and the right touch to stay safe.

Frank Nelson, a Danish immigrant with a hankering for fresh seafood (and getting the hell out of Denmark), opened his small oyster house in 1896 and shared his love of the grayish shellfsh with others. Back then, Frank used an 80-ft. sailing schooner, the Nellie Meta, to dredge and take oysters to market in Mobile. Later, he bought the Mary Etta, a 46-ft. sailing vessel, which later was rigged out with a small engine and became one of the frst shrimp boats in the region. As the years passed, the business grew, new generations of Nelsons carried on the family tradition and seafood became a more popular component of the American diet. Now, Bon Secour Fisheries operates a sprawling 30,000-sq.-ft. seafood processing plant, a feet of boats and an impressive collection of 15 refrigerated trucks delivering seafood all over the nation. Remnants of the hull of the Mary Etta, long since retired and weathered by time and hurricanes, still sit proudly next to John Ray Nelson’s (the grandson of Frank) home in Bon Secour as a reminder of a simpler time gone by.

During Mary Etta’s heyday, recreational angling was a fraction of what it is today. And, it was mostly about hook it and cook it (and freeze it). I recall fshing with my dad and catching 50 or 60 Spanish mackerel on many summer mornings to feed an army of siblings, cousins and moochy neighbors. We weren’t concerned about overfshing, and anglers weren’t organized into action groups. They didn’t need to be.

“It really wasn’t until restrictions started getting put in place on recreationally important species like red snapper that CCA and other groups started getting involved and wanting a place at the table,” Nelson said. “And rightfully so. They should have a strong voice. But, the truth is, sport fshermen came to the party later than commercial fshermen. My father was a charter member of the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission right after it was chartered in the 1960s. That was the management entity in the Gulf until the Magnuson Act was passed in 1976.”

Even though recreational fshing organizations were late-comers, their memberships have exploded and their accomplishments have been astounding. Everyone from the Coastal Conservation Association (CCA) to the Bonefsh & Tarpon Trust to the Guy Harvey Ocean Foundation and dozens of other non-proft groups lobby on behalf of sport fshermen every day, with a primary goal of creating strong, sustainable fsheries.

But, it’s fair to say that visionaries in the commercial fshing industry were early adopters of sustainability. For example, one of the frst conservation eforts in the Gulf of Mexico was spearheaded by the commercial industry when shrimpers realized they needed to protect a critical shrimp nursery in the southern Gulf.

“Bon Secour Fisheries was one of the frst members of the Southeastern Fisheries Association,” Nelson said. “This was the group that led the charge to protect the Tortugas shrimp nursery grounds back in the 1970s before it became popular to manage a resource. It was somewhat controversial within the association and SFA lost membership over that whole movement. But it needed to be done. The SFA was able to bring about the regulations to allow enforcement of a closed nursery zone. Today, more than 40 years later, it’s still a vibrant area for harvesting local shrimp.”

INSTANT REEFS

When the artifcial reef craze took of in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Bon Secour Fisheries, and other shrimp companies dependent on shrimping of the Alabama Coast, proposed a 1,200-sq.-mi. reef zone of of Alabama’s coast that would be designated for sportfshing and diving reefs. Chris’s older brother, John Andrew Nelson, is the president of the family-owned company and is a hard-core sport fsherman and diver. “We ofered the reef zone solution so that there would be a separate place for reef building while making sure shrimpers wouldn’t foul their nets on old washing machines, tires and any number of things out there,” he said.

The plan worked. Sort of.

“Even though the reef zone is huge,” said John Andrew, “our boats would still pull up registered materials that were fve or 10 miles or more outside of the designated area. We knew there was no way they had been moved that far by storms.”

And therein is a perfect example of the difculty law enforcement faces when having to patrol vast areas of water. It’s simply impossible to make sure everyone is following the rules. And while school buses, old boats, cars and rusted out appliances have proven to make great reefs for attracting fsh, they come with their own set of problems.

Bon Secour Fisheries has been a pioneer in conservation, especially in the shrimp industry. It helped promote early eforts to protect shrimping grounds in the Gulf in the 1970s. Photo left: ASMC.

“Eventually, we came to an agreement over more sensible materials, such as concrete reefs and pyramids, rather than old car bodies or washing machines that break apart and end up in our nets,” John Andrew said. “We learned that the best, long-term solution is to build a reef that will stay put and won’t break up over time.”

THE ODD COUPLE

It’s no secret that the marriage between commercial and recreational fshermen has been rocky, to say the least. Anglers get upset that commercial companies fsh legally all year (based on catch quotas), whereas recreational fshermen have short fshing seasons as well as bag limits. The battle over who gets what has raged for years. However, the tide may be changing.

“The commercial industry lives on the same resource as recreational industry and the charter boat guys do,” Chris Nelson said. “The bottom line is that it’s in everyone’s best interest to work toward the common goal of sustainability.”

Working together seems to be a recurring theme these days. Part of the reason is that a new, common enemy has begun to emerge, like a bad neighbor moving in next door and strengthening a failing marriage.

“We’re getting more agreement because of the third party that’s sitting at the table now that is beginning to work against both commercial and recreational sectors, and that is the extreme environmental NGOs [non-government organizations],” Chris Nelson said. “Their perspective is that the only way to really make sure the resource is protected is to close it to all fshing. Those kinds of extremes hurt everybody, even though that seems to be their goal.”

John Andrew agrees. “There has to be a balance rather than just a preservation, reservation, resource-frst attitude. Of course, we have to protect the resource, but just shutting it down is not management. And what we need is wise-use management.”

YOU ARE WHAT YOU ARE AND YOU AIN’T WHAT YOU AIN’T

John’s point about managing the resource over pure protectionism is not just wishful thinking by a businessman/sports fsherman. It’s been proven countless times with species on land and sea. In fact, the very critter that began Bon Secour Fisheries—the humble oyster—is a perfect example of a species long managed that we are still enjoying. Today, Nelson Brand Oysters are sold in more than 20 states at a clip of fve million pounds per year. A staf of 30 oyster shuckers pop open thousands of oysters each day—all by hand—keeping one eye on quality and the other on the sharp blade in their hand. All told, they’re shucking and shipping more than 30 million oysters annually!

This success has come from both smart management and innovation. Over the years, as water quality issues pressured naturally grown oysters, Chris and his team developed unique techniques to grow oysters of the bottom. Some growers in the Gulf region are using that technology successfully and expansion looks promising. But most oysters are still pulled from the bottom using tongs as it’s been done for years. And, from the looks of the activity at Bon Secour Fisheries, more and more people are enjoying the homely, but delicious, oyster.

“The future of oysters is great,” Chris said. “The demand for local seafood keeps increasing and you can’t get more local than a shellfsh grown in your backyard. Restaurants are serving them in record numbers and more and more chefs are using them in their seafood recipes.”

“It’s also getting popular to get oysters from diferent regions like Apalachicola, Texas, and even the Pacifc Northwest, open a bottle of wine and make it a tasting experience. Each region produces diferent favors, like cheeses or wines from diferent vineyards.”

Surely, when Frank Nelson started selling oysters 117 years ago, he never thought they would be so chic. But today, oysters are making people smile just like they did then. And the Nelson family is still doing the same thing they have always done. Through all of the decades of navigating business challenges, government regulations, economic downturns, conservation eforts and having a top priority of selling safe seafood, the Nelsons have never lost sight of their roots. They continue to work hard, keeping their fnger on the pulse of the market and the resources and an oyster knife close at hand.