7 minute read

Facing the Past

by Simon Hill, FRPS

INTRODUCTION

In building the Jorvik Viking Centre, archaeologists spent years painstakingly piecing together the evidence from the long-running Coppergate excavation . Houses, fences, paths and drains were all wonderfully preserved in the wet soil of the site, but still there were questions .... Were the-houses one or two storeyed? What were the roofs made of? What shapes were the roofs?

Evidence from the small objects - lost or discarded by their original owners over a thousand years ago - told us much about the trades of the people living in the houses - one was a moneyer, another a metalsmith, yet another a boneworker.

As the Jorvik Viking Centre was recreated, every step was rechecked against the evidence to make it as true to life - as authentic - as possible. Even the sounds and smells of the city were brought to life. But one thing still eluded us - the people themselves. What did they look like?

In the end, the figures in the Centre had to be based on modem people, but the search for reality went on! In 1991, nearly five years after the Viking Centre opened, new computer and video technology at last enabled us to come face-to-face with the real inhabitants of Jorvik.

1 UNEARTHING THE EVIDENCE

Of course, the archaeologist can only meet the inhabitants of Viking-age York in the city's cemeteries. But this poses a problem. The inhabitants of Vikingage Jorvik were buried in churchyards which continued to be used for burials well into the 19th century and so cannot be excavated. However, there were a

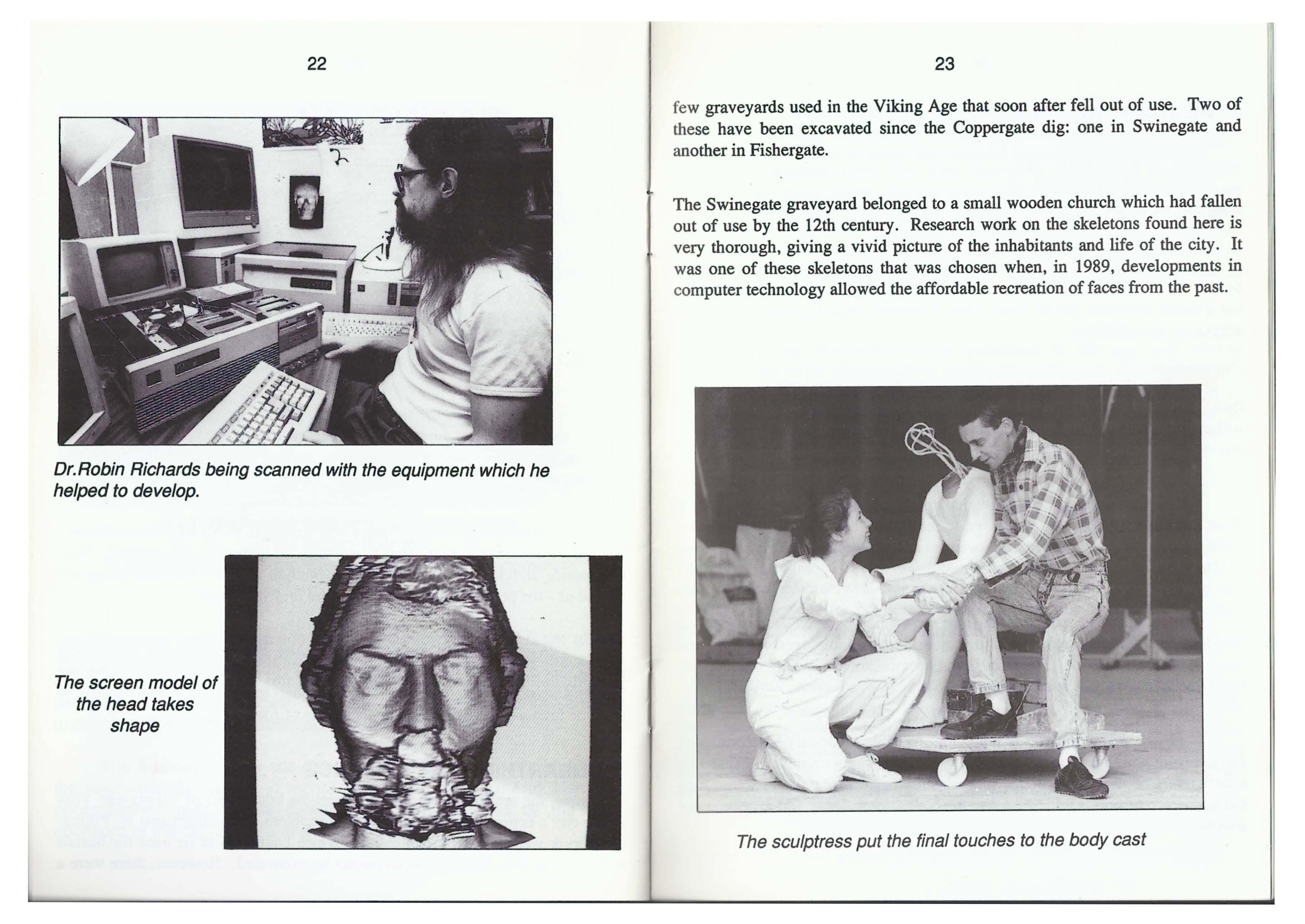

Dr. Robin Richards being scanned with the equipment which he helped to develop.

few graveyards used in the Viking Age that soon after fell out of use. Two of these have been excavated since the Coppergate dig: one in Swinegate and another in Fishergate.

The screen model of the head takes shape

The Swinegate graveyard belonged to a small wooden church which had fallen out of use by the 12th century. Research work on the skeletons found here is very thorough, giving a vivid picture of the inhabitants and life of the city. It was one of these skeletons that was chosen when, in 1989, developments in computer technology allowed the affordable recreation of faces from the past.

2 RECONSTRUCTING THE INDIVIDUAL

Whenever a cemetery is excavated, each and every skeleton is carefully photographed and recorded. The bones are then lifted, boxed and sent to a specialist for closer examinatio•n.

Although from a s~eleton we can't tell a Viking from an AngloSaxon, we can distinguish between a man and a woman. A man, for example, has a much narrower pelvic cavity than a woman, whose wider cavity is an adaptation for childbirth .

The skeleton also provides clues to the age at which an individual died. With those who died before the age of 20, it is possible to be accurate to within about five years. However, for older people, where skeletal changes are less obvious , it is much more difficult.

From the evidence that we have, it appears that only about half of those born in the Viking Age survived to the age of 20. It is also evident that more women than men died in their twenties and early thirties. This could well be due to the hazards of pregnancy and childbirth.

On the whole, people in the past were not very much shorter than our grandparents . The average height for a man in the middle ages was 5'7" and for a woman about 5'2". Today men and women are, on average, about 1.5" taller due to a good and balanced diet.

From the skeleton, it is sometimes possible to identify a deformity or disease from which a person suffered. Bowed legs suggests rickets, caused by a deficiency of vitamin D in the diet whereas fused or deformed joints may indicate osteoarthritis. Old fractures to the bones, tooth decay and abscesses are also easily found.

Most diseases, however, leave little or no trace on the skeleton and so it is often impossible to determine the cause of death of a particular individual. Only in very few cases do things like unhealed wounds provide some clue.

So the skeleton can reveal many clues. It can tell us the sex of a person and how old they were when they died. It can give some idea of the diseases from which they suffered, and sometimes how they died. But now, we can do more. Using the skull, the actual face of an individual can be reconstructed.

For the first archreological application of this new and exciting technique, one of the skeletons from Fishergate was chosen. The skeleton told us that the individual was a man, that he was about 5'6" tall and of slight-tomedium build. Although only in his late twenties or early thirties when he died, there is no evidence for disease on his skeleton, or any clue as to how he died.

3 FACE TO FACE WITH THE VIKING AGE

The facial appearance of any individual is dictated largely by the shape of the skull. Given an intact skull together with information about the sex, age and build of the person, it is possible to reconstruct the muscle groups of the skull and so reveal the features of that individual.

Until recently, this could only be done by specialist medical illustrators having a thorough knowledge of anatomy and great artistic skill. The process is slow and expensive, with many hours spent drawing and r drawing. So, it has only been the faces of the great and famous that have h n reconstructed - Phillip of Macedon (the father of Alexander the Great), and King Midas (the man with the "golden touch").

To reconstruct the faces of whole populations - which is what we need to do for the Viking Centre - demands a technique which is much faster and cheaper. Working with a team of computer scientists at University College Hospital, in London, we have at last found such a technique.

As a skeleton lay buried in the ground, the weight of the earth above it could cause some damage. The skull, being hollow, is particularly at risk. Missing parts of the skull are filled or reconstructed using plaster of Paris. Much care is taken to follow the shape of the intact pieces.The repaired skull is then mounted on a turntable, towards which is directed a low-power laser beam. As the skull rotates, the beam is reflected back from every contour, pit and blemish of its surface. This reflected light is recorded not by film but by a video camera linked to a very powerful computer.

It is then necessary to find someone of the same sex and build as the individual whose face is to be reconstructed in this case a slightly-built male. His hair and beard, if he has one, are dusted with talcum powder to ensure they reflect the laser light. His head is then scanned in the same way as for the skull.

Face to face with Eymund for the first time in 1,000 years.

When both the ancient skull and modem face have been recorded the two are combined in the computer .... the modem face is mdulded around the skull. As it is the skull and facial muscles that dictate the shape of the face, the reconstruction looks like the historic and not the modem person!

How do we know that this technique works? Where the skulls of unidentified murder victims have been used, the resulting faces have been recognised by their friends and relatives. Forensic data has then confirmed the identity of the unfortunate victims.

Our technique, however, doesn't stop here. The computer used for the recreation can also drive a milling machine. This allows us to shape a block of hard foam into a 3-dimensional model of the face. This model, together with detailed still photographs of the original skull, allows a sculptor to recreate the face with life, expression and colour.

The sculptor can also add the features that do not remain on the skull and cannot, therefore, be recreated by the computer. Features such as the shape of the nose and ears or the colour of the eyes and hair can, as with the murder victims, be predicted with some accuracy.

We can now, for the first time in a thousand years, come face to face with an inhabitant of Viking-age York.

Over the next few months, more of the figures in the Viking Centre will be replaced with recreations of the real inhabitants of Jorvik. At last the streets and alleys of this Viking-age city - found by archaeologists over ten years ago - will be populated by their original inhabitants.