THE DECISIVE MOMENT

Sub Group Organisers:

Northern: Gordon Bates LRPS docnorthern@rps.org

Southern: Mo Connelly LRPS doc@rps.org

Chairman : Mo Connelly LRPS

Retired from the UN refugee agency after a career as a workaholic, frequently living in a tent on remote borders in troubled regions. Have now achieved my work-life balance by getting a life after work. What do I like? Photography, photographers, being at home, travelling and people who respect human rights. What do I dislike? The fact that I am becoming a grumpy old woman and actually enjoying it.

Treasurer : Justin Cliffe LRPS

I have been interested in photography since my late teens however family and work commitments took then priority and I’ve really only got back to it over the past 5 years since retiring from a life in the City. I joined the RPS, and the Documentary group, about 4 years ago and was awarded my LRPS in 2013. I am also a member of Woking Photographic Society and the Street Photography London collective. My particular interest is ‘street photography’, something that I’m able to combine with my part time work for a charity in London.

Secretary: David Barnes LRPS

I have been interested in photography since childhood and have been actively taking and making images for many years with a few lapses caused by work and the onset of family responsibilities. I retired in 2005 after a career in the IT industry. I have since combined sport spectating with photography – I spend most Saturday afternoons in winter kneeling in the mud, camera in hand, at my local rugby club. I feel at home in towns and cities and spend time in London where there is always something happening that seems to me to be worth recording.

South East: Janey Devine FRPS docse@rps.org

Thames Valley: Philip Joyce philip_joyce@btinternet.com

Committee Member and Coordinator for DG Sub-Groups: Gordon Bates LRPS

I joined the RPS in 2013 and was awarded my LRPS in 2014. My main interest is in documentary and street photography and I have been a member of the Documentary Group since joining the Society. I was instrumental in forming a Documentary Group in the Northern Region in 2015. My other involvement with photography is as a trustee and board member of the arts organisation, Multistory, in the West Midlands.

Committee Member and Decisive Moment Editor:

Turley ARPS

Photography has been part of my life ever since I was at art college. After a trip to Nepal in 2006 my passion was ignited and I’ve been developing my photographic abilities ever since. Having experimented in a variety of photographic genres I now focus on longer term documentary projects. I’ve worked closely with commercial photography throughout my career in advertising but enjoy all forms of documentary and travel for my personal work. I joined the DG to be part of a like minded community of peers and by happy chance have ended up editing our groups digital magazine.

Committee Member and Group Webmaster: Steven Powell

I have enjoyed a turbulent relationship with photography over most of my adult life with my technical ability often letting down my vision! Nevertheless I’m always ready for that one-ina-million shot which makes every thing worthwhile. I joined the Documentary Group in 2016 to see more examples of the style I love so much. As well as looking after our website and bimonthly competition, I’m occasionally called on to document interesting events at work to help promote the efforts of other teams. I’m aiming to achieve the LRPS accreditation (and catch up with the rest of the team).

DM Editorial team:

Sub Editor: Belinda Bamford

Sub Editor: Dr Graham Wilson

And the rest of the team:

Bi-monthly competition manager: Steven Powell

Social Media: Steven Powell

Flickr: Chris Barbara ARPS

6 A Word From Our Chair

8 Interview with Emma Chetcuti - Director of Multistory

20 Winner of the 6th 2017 Bi Monthly Competition Winner

22 Winner of the 1st 2018 Bi Monthly Competition Winner

Member Images

24 Barra Bromley - Uzbekistan

30 Carol Allen-Storey - Bad Blood

42 Chris Jennings ARPS - A society of waste

50 Christopher Osborne - Transient

58 Jagdish Patel ARPS - Desi Pubs

66 Rob Kershaw ARPS - Tokyo suburb of Shimo Kitazawa

72 Sean Bulson LRPS - Retail - On the Brink

76 David Hurn - Swaps Review

I’m writing this, my last letter to you from the Chair, from Orkney. A region I love dearly. It has history, wonderful scenery, untamed sea and shoreline, interesting towns, a whole host of different islands, varied flora and fauna, and very friendly people. You can overdose on photography, no matter what your interest, or you can just enjoy it. It also rains quite a lot!

Another great edition of DM this month, looking at Social Documentary photography. The last two issues have seen interviews with David Goldblatt and Polly Braden. Both have been involved with Multistory, a West Bromwich based community arts organisation. So for this edition we decided to look in more detail as to who and what is Multistory – an organisation that uses photography as a means to document life in the Black Country. And they are inspirational.

In January we sent out a survey, the first we’ve done. Approximately 30 percent of members completed it and we are busy reviewing the information, including by region. This will form the main input for our Doc Volunteers Day, when we get together with Doc Regional Coordinators and volunteers to discuss a plan for the next couple of years.

We’ve held two Ali Baskerville documentary storytelling workshops already this year – one in Salisbury (Doc South) and one in Norwich (Doc East Anglia) both oversubscribed and we anticipate a further two during the course of the year.

There will no doubt be changes to the way Doc (and other SIGS) do business in the coming months as the new data protection regulations come into force. We’re still awaiting the legal position from RPS Headquarters and to hear what organisational changes will be made, and we will be in touch on these as soon as we know.

The RPS Board has published a new strategy (you can find it on the RPS website). Whilst it has some great aspirations to improve our standing in the photographic world and to meet our commitments as a charity, it has nothing to say about membership or what Groups and Regions should be aiming for. However, Doc will be finalising its own plan of action after the Doc Volunteers Meeting and the AGM.

The AGM this year is on 29th April and you would have received, or are about to receive, the relevant papers. At this meeting I will stand down as Chair, and hopefully by the end of the meeting you will have a new Chair.

It has been both a pleasure and a great learning experience to be Doc’s Chair for the last five years. I have met many wonderful people, who are also photographers, I’ve been involved with all aspects of the development of the Group and proud to see it grow to its current membership. I have also learned how inept I am at all things technical – I prefer to put it down to my genes rather than my age. However,

there is a wonderful Committee who have been able to get me out of all messes I have made or have been about to make. Since the beginning of my time with Doc I’ve worked with Justin Cliffe, who is the most competent Treasurer that any Group could wish for, and the knowledgeable and experienced David Barnes, who most recently covers both Membership and Group Secretary. In the last three years we’ve been joined by Gordon Bates, who set up the first of our Regional Groups and who paved the way for the five other groups we established. We’ve even managed to recruit two younger Committee members (rare in the RPS) Jhy Turley who edits and publishes Decisive Moment and Steve Powell who took over as webmaster and manages Doc’s bi-monthly competition – both of whom have a passion for documentary photography and technical skills (a marriage made in heaven for the Documentary Group).

In addition to the Committee, we have a set of volunteers, who run our Regional Groups, manage DPoTY, help on Decisive Moment and generally take on tasks when needed. Without all these people we wouldn’t have a Doc Group.

Thank you to all of them.

Finally, thank you to all members for an interesting five years. I look forward to as many of you as possible making it to the AGM in late April and to staying in touch after April.

And now, more photography for me.

Best wishes

Mo Connelly, Chair, RPS Documentary Group

You may recall our two most recent interviewees, David Goldblatt, HonFRPS (davidgoldblatt.com) and Polly Braden (pollybraden. com), both worked on photo projects with Multistory (mutistory. org.uk), a West Bromwich based arts organisation covering the Sandwell area of the Black Country. David and Polly are not alone amongst prominent and passionate photographers who work with Multistory. Based in West Bromwich Multistory works with outstanding photographers and filmmakers to make art for and about the people of Sandwell. Their projects reflect every-day life working with local residents. It seemed relevant for this issue on social documentary photography to take a closer look at who Multistory are, so I headed for West Bromwich to meet their Director, Emma Chetcuti. For me their work is inspiring and each time I come into contact with them, I wonder why there are not more groups like this throughout the country – for and about the people in their area, reflecting on and celebrating everyday life, and working with local people. The staff of Multistory are very special and this is no doubt the main reason for their success.

Another possible reason is the way Multistory evolved from earlier organisations, already grounded in the community, and had the foresight to change with economic conditions.

I asked Emma to tell me who she is and what is Multistory:

I went to University in Newcastle, have a background in Community Arts and Community Theatre, and worked in that area for a long time. I moved to Birmingham to do a PhD. in Post-German Theatre. I’d always been interested in political theatre, theatre that used mask and metaphor, and that engaged with communities outside of the traditional theatre spaces. I’d always had an interest in photography. My family are artists and we always had art and photography books in the house. When I came to Birmingham I met people working in photography. I started work with Jubilee Arts, a well-established community arts organisation based in Sandwell. They made powerful community projects and after a year they offered me a full-time job. We were working in community settings using theatre, music, all sorts of art forms and photography. The Director was a great mentor to me. She developed the ideas for ‘The Public’ a big arts centre in West Bromwich, which grew out of Jubilee Arts. Sadly this closed due to a lack of funding. The ethos was a place where the public could make and engage with art, and a place for them to work.

This is a poor area, the local authority was strapped for cash, and there was a new Government that didn’t invest in the arts, in the same way as previous Governments. It was very hard for both the local Council and the Arts Council. It was a great shame that it closed, as places like West Bromwich deserve to have great art centres for local people. This is what brought me here. I wanted to work with people, to make art projects about their lives.

When the Public closed, everyone was made redundant, and the Arts Council and Sandwell Council approached me to see if I would stay on to run the community side of the project. People didn’t want to lose the arts centre but it was a building that was no longer viable. I agreed, on the condition that I could establish a new company. That was in 2006 and we worked with the Arts Council and Sandwell Council as well as a number of consultants in order to put a business plan in place. The Arts Council and Sandwell Council guaranteed us funding for three years.

We inherited a number of projects that the Public had been involved in, which were very traditional community arts projects – working in housing, health and under-fives. Bringing artists to those environments to make art that might have a public art outcome, which we could deliver for a couple of years.

In 2008, I was able to look at the work and reappraise what we were doing. We knew in the light of the economic downturn there wouldn’t be big public programmes and there would be cuts, so we had to review operations and cut back on costs. We reduced the staff from 14 to 4, and we looked very closely at how we could make powerful art projects with communities. For me the important thing was that the art had to stand, as great art does, in its own right. And that hadn’t been happening with previous projects. So, we worked with a consultant to restructure and commission differently. I knew instinctively that working with photographers would be a great way to include local people and tell stories about life in this area.

The Black Country is not a unique place, it’s a post-industrial working class community, and similar to other post-industrial areas in the UK, in that the stories of this area are invisible. We have a press that is focussed on what is happening to people in London. We wanted to find a way to create art projects that told stories about local people’s lives.

To approach photographers seemed the best way to do that, in particular photographers who made documentary work. We were at a point where we’d reduced the size of the organisation, were small and that meant we could work in a different way. The first photographer we approached was Martin Parr (martinparr.com). I remember trying to write an email to him and writing it about ten times – trying to explain who we were, what the Black Country was, and why he might be interested to come and work with us. In the end I reduced it to two sentences, crossed my fingers and hoped he’d get back in touch. And he did. He said he was interested enough to come and visit us. He drove up one day and we talked about how we could work together. Martin understood what we were trying to do and who our audience was. The work would be seen in community settings and something we could distribute quite widely. He suggested making a newspaper. The idea was to work with him for a year. Working with Martin we established and learnt a way of working. We were on a journey where we were discovering new things. Martin is a very efficient photographer – he started work at 9 o’clock in the morning and we quite often finish at midnight. He would come up for four or five days in a row and would say to us in advance ‘These are the places I want to go. I want to visit health centres, community centres, I want to spend time walking on the High Street, I want to go to Working Men’s Clubs and factories and foundries and temples and schools’. We would be his fixers. Fix his shoot schedule before he came up so that all the permissions were in place and that’s how we could be efficient. That meant Martin wasn’t wasting his time and when he was here, we could just meet people and he could make his photographs. We became a very efficient unit. We were at the early stages of working out what Multistory was.

During the first year that Martin was here we developed his shoot schedule for him, and it was important we were with him when he was out and about, as it was an opportunity for us to reconnect with community groups, to hear their stories and also promote Multistory and what we were trying to do. We were also able to pick up on other stories for Martin for his next visit. We learned how Martin worked. He has incredible insight, he relates to people from all sorts of backgrounds, is able to fit in with anyone and is interested in people’s lives and stories – always listening to them. It sounds a strange thing to say, but Martin introduced us to the Black Country. One of the things to understand, as a photographer you’re given permission to go into places you wouldn’t normally go. The other is that because Martin is a great enthusiast, he is always looking at the works of other photographers, and would regularly give us books. This was the beginning of us understanding that we were part of a tradition, a strong British documentary tradition, which is probably celebrated more abroad than it is in the UK.

We also started recording oral histories, documenting peoples ordinary everyday lives and to make films. Martin made four films with us in the Black Country; ‘Teddy Gray’s Sweet Factory’, who managed to keep their traditional handmade sweet processes, with a staff who have worked together for a very long time and made sweets loved by everyone in the Black Country; ‘Tudor Crystal’ the last glassblowing factory in Stourbridge; ‘Turkey and Tinsel’ a story about a group of old age pensioners and their coach holiday to spend a pretend Christmas in Weston Super Mare; and the final film ‘Mark to Mongolia’ about Mark Evans from Wolverhampton, a pigeon fancier who traded his pigeons in China.

So that first project, Black Country stories was a celebration of Black Country life. Before the Public Art Gallery closed we had an exhibition there. We had a wonderful time doing the project, but we weren’t sure if any of the participants would come to see the exhibition. For the exhibition we decided to show the whole of the photographic archive – over 600 10x4 images, that we pinned up on one huge long wall. Then we selected 28 larger prints that became the exhibition proper. On the first night we held a special VIP opening where we invited local people, so we could spend time with them. Over 600 people came to the exhibition and we could not believe it. It reassured us that our approach, focussing on the lives of local people and concentrating on working with them, was something they would come and see in exhibition form. We then worked with Martin and Dewi Lewis (dewilewis.com) to produce a book and other galleries became involved. In the end it was a four-year project and created for Multistory a foundation from which to make other invitations.

Now we’d developed a way of working with photographers, connecting with local communities and producing high quality photographic exhibitions, which were also part of our on going digital photographic archive about the Black Country, as well as, publications that we would give back to local communities. Importantly, everyone who had their portrait taken was given a free 10x8 Martin Parr print, and this is something, that has continued with all our commissions.

We started to look at other opportunities to broaden the invitation. Martin supported us and encouraged us to look and think quite widely. So, we approached Mark Power (markpower.co.uk). We were particularly interested in how he might approach the urban landscape of the Black Country. Because we’d started to build our reputation and our ability to work with photographers, we partnered with the New Art Gallery in Walsall to have an exhibition with Mark and published a magazine as well.

The intention is not only for a photographer to come here and work with Multistory where we work as their fixer, producer, and bridge within the community, it is to help them connect with local people and the story they want to tell. A lot of the photographers we approached at first were very established, and who have a reputation that is not just national, but international. The reasons for this, is we were just starting out and we needed to find ways to secure income, so we could continue this important work. We wanted to work with photographers who were not only recognised, but who were able to work in a community context, to make slightly different bodies of work, and who could adapt to how we worked. We wanted to build on this foundation so we could create opportunities for local and regional artists to work with the photographers we were bringing in. In particular, we partnered with the photography department in Sandwell College to give an opportunity for young photographers to meet some of their heroes in the photographic world. This was a powerful message to send young photographers that it was possible to work where you come from. We wanted to make opportunities for younger photographers.

We approached Liz Hingley (lizhingley.com) and Mahtab Hussain (mahtabhussain.com), young photographers from the area who were just developing their practice. They have both made very powerful bodies of work.

Mahtab Hussain is making really important work in Birmingham about young Pakistani men and their identity. That work has just recently had huge momentum behind it and been celebrated internationally. Before that he worked with us to develop a

project in Tipton, a small town in the Black Country where there is a small but significant working-class Muslim community, who have lived in Britain for a very long time. He made a book with us called ‘The Quiet Town of Tipton’. That book celebrates the stories of the community who post September 11th were suddenly the target of quite hostile racist abuse and treated as if they were outsiders. The book was more than a gesture, it was an opportunity for them to tell their stories and an opportunity for us to hear about their lives and how similar they were to the white working-class communities in the same area. We developed an exhibition, which toured the local libraries, and published a book, which could be distributed through the libraries and given back as a gift to the Muslim community in Tipton.

Liz Hingley worked for us in Smethwick, which is one of the most culturally diverse towns in Britain. You don’t hear the stories about how well people get on with each other, only those about conflict and tension. Liz produced a wonderful project about the food that communities share, and how people have integrated. She made family portraits combined with recipes that became part of the book. It was again a celebration of community life. An important aspect of all the projects is that we invite the people who have taken part in the project to an event where they get a free copy of the book, and equally important is an invitation is extended to the wider community so they can take part. This celebration is integral to all our projects.

We’re just about to launch a project by Dutch photographer Corinne Noordenbos, ‘Black Country Lungs’ (corinnenoordenbos.com). She was struck, when she came here, by the number of people who seemed to be very unwell. The statistics show that the incidence of lung disease, COPD, in the area is very high, due to a mixture of the industries people have worked in and the fact that people have smoked. That has had a very detrimental effect on people’s health, and this is their story.

We’ve worked with many great photographers, local, national and international and found many different ways to present stories. Each photographer has to find his or her own way and this takes time. For example, we worked for four years with Martin, David Goldblatt five years, Liz Hingley and Mahtab Hussain two years. We worked with Susan Meiselas (susanmeiselas.com) for three years whilst she explored the stories of women living in refuges developing a collaborative and participatory project whereby the women also contributed their photographs and stories.

A new project is with German photographer, Walter Gehrling, who makes flipbooks with a specially adapted camera that takes 36 shots a second and then shows them as a performance, projecting the books onto a screen. Part of his practice is to walk with a tray of his

books and have accidental encounters with people. He has walked across the six towns of Sandwell. There has to be a shared curiosity and if people approach him he shows them the flipbooks and they might tell their story or meet with him again.

So, each project is unique and there isn’t a formula. The invitations are to make a connection and tell a story, which quite often hasn’t been heard before and stories that have not only a local but have a universal resonance. That is what we’re trying to do, whilst building a photographic archive that local people can access and exhibitions that tour in community settings – libraries, museums, shops, surgeries, etc. The work is taken to where local people are. We are not trying to drive them to an art gallery or art centre.

With all of our projects people are aware that they have given us permission to share their story publicly. It means that we have to go back and check that they’re happy for us to share their story, through a book or a photography exhibition and the person suddenly sees the relevance and importance of their story. They have the ability to co-produce the final product, including offering changes to text. The moment of seeing their story performed, or in a book or an exhibition, is an intense moment of realisation and pride that someone has taken time and effort to tell their story in a way that makes it different

to the everyday. That’s the thing that keeps driving us to make work in this area, as it’s quite profound and moving for participants, for us, for the artist and the wider audience. For me, that’s why it’s so important. The emphasis for us is that we are making art and if there is some change in the individual, that’s powerful. We hope for it, but we’re not doing this because we’re social workers or we think the work we’re making transforms or changes people’s lives. That’s something they have to tell us, not us tell them. I think it’s important that we remain open, humble and curious. The exciting thing that’s starting to happen is that community groups and individuals come to us now and invite us to work with them on stories they feel are important. It works both ways – sometimes we invite outsiders as they have a different way of looking at things, sometimes the commission is with local artists or photographers because they have an inside view, and other times the community comes to us as they have a story to tell.

Text is used in many of our books because we’re telling a story in the words of the community with photographs from the artist. The voice of the people themselves is really important and it’s equally important that we ensure they continue to be heard.

It’s important that the work is varied, so the photographers we invite are very different and what we produce is very different as well. At one point we were thinking about whether we needed to produce a template for the books, but it doesn’t work. The invitation is generous and open because of the effort and time put in, to build the connection with the community. Each time we take a photographer around we find new stories, it’s our way of staying in touch with the community. We learn things all the time. We have been doing this since 2006 and we need to keep finding ways to challenge ourselves. We need to keep adapting and learning.

We’re funded by the Arts Council of England and by Sandwell Council and without their investment, by both organisations, we wouldn’t be able to do what we do. We also raise funds, which accounts for one third of our income.

Last year we made a successful approach to the Arts Council ‘Ambition for Excellence’ programme. This means we can run a programme for 12 regional photographers and six international commissions towards a festival, which we are calling “Blast”, a photography festival on the streets of Sandwell. We will be working with the Caravan Gallery (thecaravangallery.photography), Eric Kessles, who works with Found Photographs, Niall McDermiad (neillmcdermiad.com) and local film maker/photographer, Billy Dosanjh. We don’t have any venues, as there are no art galleries in Sandwell, so we do ‘weekenders’, in each of the six towns, culminating in West Bromwich using volunteers. Enabling us to undertake a range of exhibitions and different types of work for the local audience. Our challenge is to find lots of local partners, including owners of empty shops, who will let us exhibit work.

We need to build an infrastructure, so work can be seen more regularly and partnerships are built with museums and libraries.

We achieve a lot with a small staff: Caron Wright, Becky Sexton, Jenny Moore, and myself. We also rely on volunteers including those from amongst the photographic students at Sandwell College, with whom we work closely.

Mo: How many other centres do you think there are similar Multistory?

Emma: In the 70s and 80s Side Gallery in the North East did this. There are lots of organisations making great photography but none who do what we do.

Mo: Emma, thank you, it’s been a great pleasure to listen to the story of Multistory.

Multistory is inspirational, and it has shown me the power of documentary story telling for everyday stories, with the words of the participants themselves, not sensational journalism, not exotic tales from far flung corners of the world, not for activist ends. These are stories, which have a resonance with others in many different places. It has also shown me the power of a small group of four people with a joint vision to work with their community and turn their stories into art. Emma makes it sound easy, but assuredly it is not. Hurrah for Martin Parr, who ‘got them’ and who not only made some great stories with them, but helped them to define their way of working. We can all learn more about our own documentary photography from the work of Multistory.

Where photographers have been named without a website, a web search will lead to lots of information about them, including Facebook pages and media interviews. Martin Parr’s four Black Country videos can be found on YouTube and are well worth a look.

We had 24 entries for the last 2017 bi-monthly competition.

Congratulations to Dawn Clifford LRPS for her winning image ‘Mona Lisa’ and her prize, the book “The Documentary Impulse” by Stuart Franklin HonFRPS, has been sent to her.

There were 27 entries for the first 2018 bi-monthly competition. As always we recieved the diverse range of images from across the group, so please keep entering your images.

The winning image was ‘Team spirit’ by Sally Norris.

‘Having put down my camera many years back and only recently returned to it (and study of photography through the Open University/RPS) this is one of the first images I took of athletes at work. Three athletes comforting one another in the midst of the fray, all Olympians as it happens, yet the strain is clear as they take part in a gruelling Tough Mudder event. I grabbed the moment, at a fair distance, and it was striking and it says everything about their team spirit’.

The 2018 competition asks members to also include a little backgroud to the image providing some context.

Please keep an eye out for details on the group RPS page for more details.

Each winner will recieve a copy of The mind’s eye: writings on photography and photographers by Henri Cartier-Bresson.

The next deadline is Monday April 30th for images taken during Feburary, March and April.

Please send your submissions to dgcompetitions@rps.org and visit the competition page on the RPS website for details.

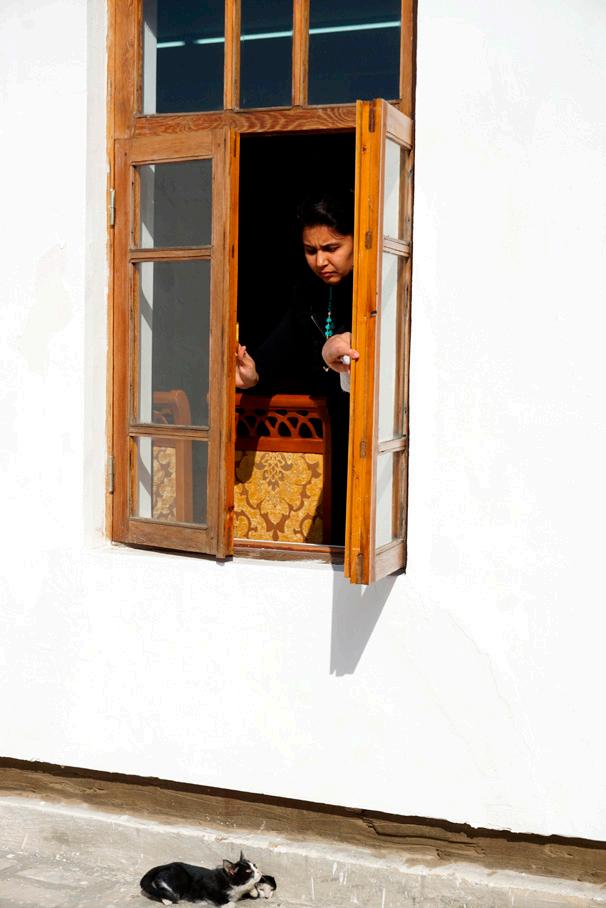

Can travel photography only be seen as an album of responses?

On returning from a recent trip abroad, I was left thinking how impossible it is to bring back a deep and overarching impression of a country. My photographs of Uzbekistan seemed to show something quite different from what I’d anticipated before travelling there.

Before I left, I did some preparatory reading, and thanks to organisations such as Frontline, and travel accounts like A Carpet Ride to Khiva by Christopher Aslan Alexander, I understood a little of the country’s tumultuous history and politics.

Despite huge social change women are still confined within traditional hierarchies. Brides remain controlled by their husband’s family. There are forced sterilisations and bride kidnappings, a custom which suited the once nomadic lifestyle of the steppes, when it was easier to steal a wife than go through the process of courting. Writing for The Gazelle (April 1, 2017), Azhar Yerzhanova confirmed that at least two bride kidnappings still occur each week, though there are also occasional staged elopements.

Although it has softened now, workers, students and teachers are still forced to the countryside each autumn to bring in the cotton harvest. Even when the government aren’t sending out orders, a pall of chauvinism still clouds everything.

What, exactly, was I about to encounter?

The quickest way to get a feel for Uzbekistan’s complex history is to travel along the old Silk Road. This trading route is probably the country’s greatest draw for visitors. Rather than encountering fearful brides, I kept meeting smiling newly-weds as they posed for their wedding photographs, using blue-tiled mosques and medrassahs as their backdrops. I also saw many fathers, collecting their children from school, and even grandfathers out with their grandchildren. I was bowled over by its stunning Islamic architecture.

Despite the years under the Soviets, and the cruelties of Karimov’s regime before he died in 2016, were other realities now taking place? Or was I simply witnessing people making light after living through darker times? I couldn’t help wonder if there was a shadow side beyond my field of vision. My photographic take on the country was inevitably limited by my lack of contacts and travel difficulties, not to mention my own deeply held political and cultural leanings. But it seems to me that unless we are journalists (with interpreters, guides and drivers), travel photographers can only bring back the visual evidence of that which touched our emotions and senses, a sort of ‘album of responses’. What hope can we have of experiencing more than a passing infatuation, when there isn’t the opportunity and time to build a more searching and critical point of view?

Why

Tashkent’s World War II Memorial

a

The epi-centre of the world’s fastest growing emergency is in Borno State in north-east Nigeria. The Boko Haram militants conduct their reign of terror from deep in the Sambisa Forest. More than 2.5 million people are estimated to have been displaced since their insurgency began, some of whom have found refuge in Internal Displacement Camps in Borno State. However, Nigeria has the world’s third largest displacement of its citizens and less than 20% of them live in these vastly over crowded camps.

More than 2,000 women and girls, have been abducted by the insurgents, and many remain in captivity, exposed to the daily savagery of rape and beatings. They face lasting consequences of the physical, emotional and sexual violence. With their villages plundered by insurgents, they often have no home to return to, and find themselves living in overcrowded displacement camps.

Their own families and communities often reject them, calling them “Boko Haram wives” fearing they have been radicalised in captivity. They suffer further humiliation when they return with babies of rape who are known as ‘Bad Blood’, which places them at risk of discrimination and further violence. Some women will even commit infanticide to prevent the stigma and eliminate the reminder that their baby was the result of rape.

UNICEF and International Alert’s re-integration programme is helping transform the lives of these women and girls, and their children born of sexual violence.

www.castorey.com

“When I first arrived in the camp, I was labelled a Boko Haram wife with a dark soul. They thought I was wicked, evil. They viewed me as impure. I was isolated, the stigma was hurtful.” Yagana

Sanda Camp, Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria

In an overcrowded women’s dorm, those who escaped from the Boko Haram find refuge and friendship amongst others who shared their fate.

They now live in relative safety in the Sanda Camp. Some of these women shared a harrowing story of when they were captive by Boka Haram how the insurgents would enter the women’s dormitory. They learned to lift their robes for the men to inspect our bodies and choose who they would rape.

Sanda Camp, Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria

Dorcas Musa escaped from the Boko Haram. She preferred to die on the run than remain in captivity.

“The Boko Haram invaded our village and took me captive when I was 13. We were given to one of the Boko Haram’s wives who treated us as slaves. After a tortuous time, I preferred to die and escaped to an IDP camp. There is enormous mistrust of anyone who escapes from the insurgents. They think you have been radicalised and will harm them.” Dorcas

Eyn IDP Camp, Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria

Members Images - Carol Allen-Storey

Fidele’s young twins sleep peacefully on the warmth of their mother’s lap as she reveals her ordeal being a captive in a Boko Haram camp.

Sanda Camp, Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria

FATIMA SALISU – Displaced mother and child

“I fear for my life, I fear people will beat me so I stay close to my tent. There are continuous threats from many people here because they fear I am Boko Haram and will harm them. “I escaped from the Boke Haram and now live in this Internal displacement camp with my adopted son. We live in fear; we have no future, our life hinges at the edge of humanity.” Fatima

Dalori IDP Camp, Borno State, Nigeria

The old flame of love rekindled. Maryam looks lovingly at her husband Zanna. They were reunited after she had been abducted by the Boko Haram, for more than 18 months. This, a story of love about a man accepting his wife after she had escaped from abduction by the insurgents.

Dalori IDP Camp, Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria

Pages 38-39

The landscape in an IDP camp takes on the persona of being permanent; tents become replacement for homes lost through violent conflict. The Dalori camp houses over 25,000 residents; some have been living there over 5 years. The land was originally a part of a local university but was seconded to accommodate the displaced families whose homes were torched by the Boko Haram.

SANDA CAMP, Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria

UNICEF has created safe playgrounds in this IDP camp. These children, mostly do not attend school find this specially created space a welcome opportunity to meet peers and share their play-time.

IDP Camp, Borno State, Nigeria

Pages 40-41

Mid-day, in the heat of the blazing sun, a young girl, who had not eaten for the last two days, rests her weary body on the earthen floor, detached from her surroundings. Tragically too often there is little food available on a daily basis. The consequence is many of the children suffer from acute mal nutrition.

Dalori IDP Camp, Borno State, Nigeria

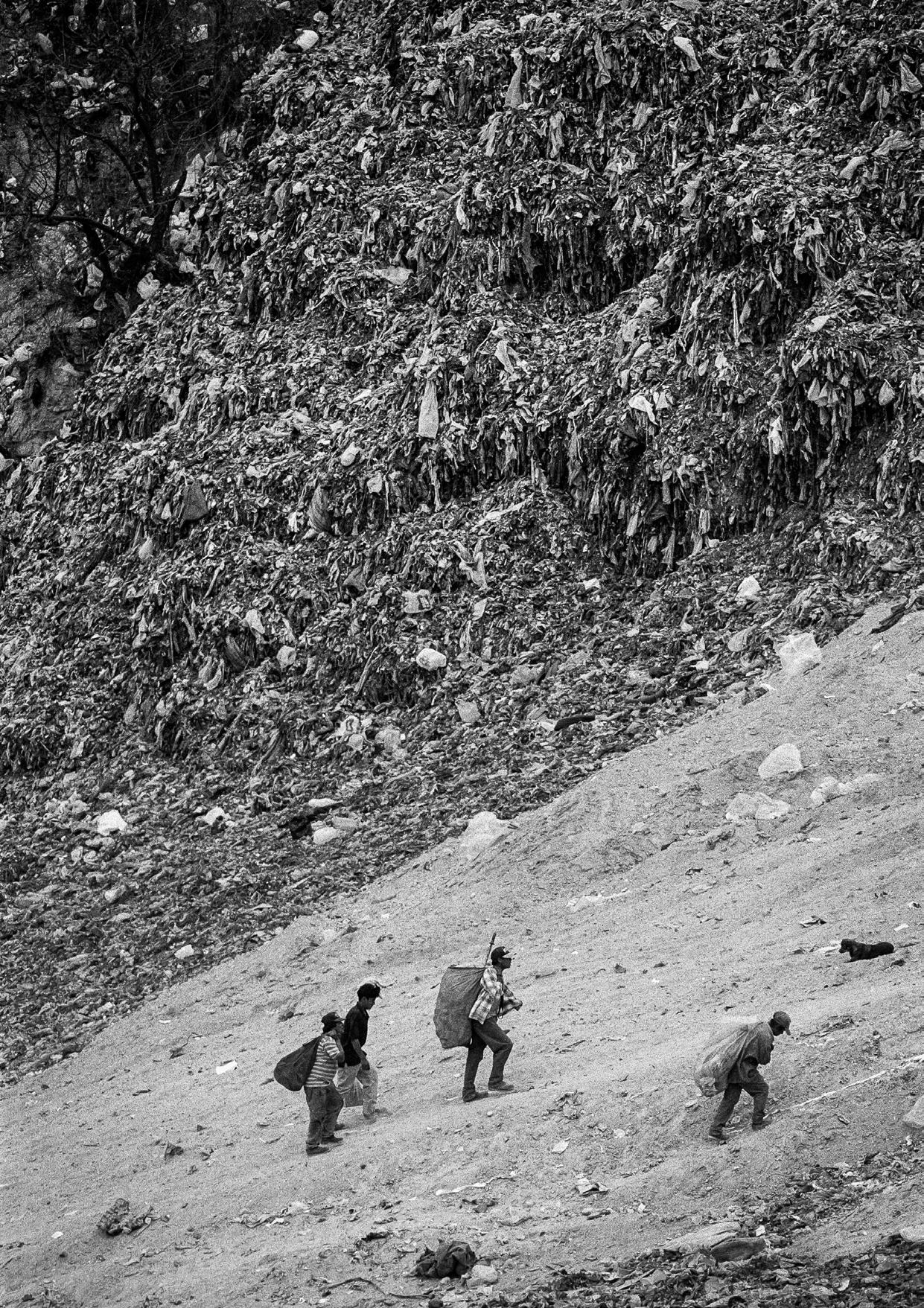

These photographs were taken when I worked as a water and sanitation specialist for an international development bank, at sites in large cities in Central America where I assessed projects for the safe disposal of solid waste. As the random collection of images became a project, I asked friends at the various places I visited to take me to meet the people that lived on the margins of our society depending on what the rest of us throw away.

These were not the controlled, sanitary rubbish disposal sites of the industrial world, but open depositories of waste. The air is filled with the smell of decay and the smoke of spontaneous, methane-stoked fires. Who are the people that risk so much to squeeze an existence out of our waste?

I do not know which came first; realising that those that live with our waste are as much individuals as anyone else and deserved photographing, or whether this appreciation was the result of making the images. My first pictures were shot at a distance with no specific purpose; the people, so small and distant, seemed a race apart.

As I got closer, I saw each person as an individual. Some go off to their tasks in the morning: collecting bottles, cardboard, or aluminium cans; others mind the locations where the material is stored. One family specialises in bronze, another sells homemade drinks from a cardboard shack. Children play; children work. Like the rest of us, some are proud, others humble; some open and garrulous, others reserved. Some dominate, others subjugate; some hide and others approach.

This is a document about the individuals: who they are and the conditions they work in. It is a simple portfolio of portraits of people, in their environment, who are every bit as unique as the rest of us: all members of a society of waste.

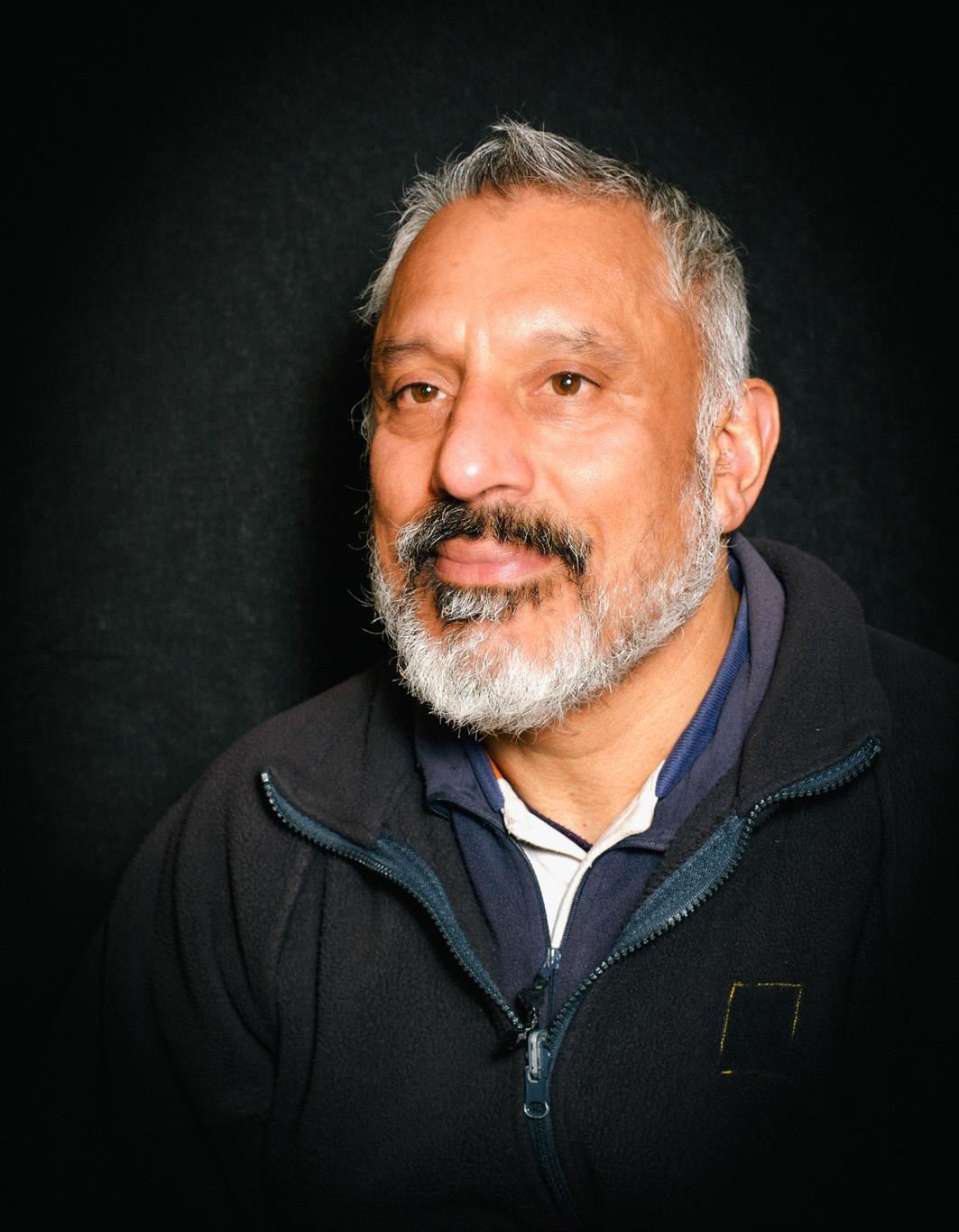

“Transient” began on Friday 9th June at 6:30am – give or take a few minutes. It was Ramadan, and my friend Bernhard and I were out early to make images of the shape and texture of old Dubai before the day became unbearably hot.

A street cat appeared from around the corner of a building on the edge of the Souq al Kabeer in Bur Dubai, and Bernard immediately lay down to take its portrait. Behind us, a merchant was setting up the display outside his little shop. He saw my friend fall to the ground, and literally threw down his merchandise, sprinted down the rickety wooden stairs, and ran to offer assistance.

Once I’d assured him that Bernhard was not having a heart attack and all that was well, I couldn’t help but reflect on what had happened. Here we were in one of the poorest areas of Dubai and a stranger had demonstrated a touching degree of humanity. From that moment, I knew that I wanted to capture the human side of old Dubai.

The area is best described by suggesting that you imagine yourself in a strange land where the sound of commerce rings out in unfamiliar languages. It’s a place where traded commodities are moved through the efforts of men and not machines. These men have bound together by the common experience of economic migration, enjoying beautiful winters and enduring blistering hot summers.

One finds an abundance of human spirit, warmth, and camaraderie. These people are not wealthy, and do not inhabit modern glass and stainless steel houses. But they live real lives judged not by the colour of one’s skin, or by one’s religion, but rather by your demeanour to all of humankind, and by your actions. These people have nothing in common with those living in the modern suburbs and shopping malls just a few kilometres down the road.

The underlying narrative in this work is a celebration of a place that fosters the best of humanity, and a place where there is no prejudice. It also documents social movement and transition of a migrant workforce. I set out to capture the temporary nature of the urban landscape in a place in which over eighty five percent of the population live today, yet will one day have to leave. The immigration laws in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), welcome migrant workers, but equally ensure that they leave when there is no more work, or when they retire. In compiling these images, I celebrate Dubai’s cultural diversity. While many of my subjects have grown up in vastly different backgrounds to my own, we share a similar story. We are all in this country to earn money to support our families, and to create a better future for when we return to the place that we call home. We all find a way to live peacefully together, despite our differences.

There is a depth beyond the clichéd contrast of hand loaded wooden trading vessels moored next to a road bustling with expensive Japanese 4x4’s. We have Iranian, Indian, and Pakistani workers and merchants who are at the coal face of the Dubai trade machine; meanwhile Emirati women shop in the souqs watched by tourists from Oman, Saudi Arabia, Korea, China and the West.

Embedded in this series of images is another contrast too. Some nationalities, particularly those from the East, are honoured to have their image taken. It is common to be stopped as I walk the streets and docks, by men asking me to take their photo. Yet they live in a completely different society. One which has designed and implemented some of the most protective privacy laws in the world. Throughout, I have worked within a legal framework rigorously designed to preserve the ideals and individual rights of the most conservative groups in society against the modern intrusions of the paparazzi and social media.

http://image.photography/1/transient-gallery

A Midlands based photographer, I often work with galleries and museums, which sounds rather middle class. The idea that art is the preserve of the middle class is real, and one aspect of social policy deliberately aims to tackle this by trying to encourage ‘socially excluded’ people into galleries. There is even a performance indicator which correlates lack of ‘social mobility’ with not visiting galleries. Clearly, if you are going up the social ladder, you must want to visit your local gallery, but what if you are happy not climbing the social ladder and don’t want to visit the local gallery, does this mean you aren’t engaging with any art or culture? Clearly, there is a class assumption underlying this social policy.

One reason some people don’t visit galleries is that they don’t see their lives reflected in them. If you visit galleries in the Black Country you see works by artists such as Turner, Richard Chattock, Edwin Butler Bayliss, Harry Norman Eccleston and Arthur Lockwood. Beautiful landscapes, and plenty of portraits of rich people, but rarely will you see the local working-class community (a rare exception worth seeing is Andrew Tift’s work, Three Steelworkers).

One local group, Creative Black Country, recognises this and makes art for local people, and leaves it with them; the Desi Pubs project is one example of this approach, in which

I documented several South Asian Black Country pubs, their owners, staff and punters. Originally, I thought that the project was primarily about the dislocation of the Asian landlords running Black Country pubs, but you quickly realize that almost everyone who comes to the pub is slightly out of place.

The word ‘desi’ is commonly used to refer to people, cultures, and products from South Asia, and although the project is about this community, it is also about something else. The original Sanskrit word, desha, referred to people from a specific place or land, and in these pubs everyone seems to share a common bond about being from the ‘Black Country’, (itself an imaginary place) with most people talking about coming to terms with the changing local landscape. Most of the local punters talk about the decline of the local manufacturing industries. For example, Rowley Regis grew from its iron ore, stone and coal and this made it a central location for heavy industry, many of the local men worked in the same factories, on the same machines, as their fathers and grandfathers. It’s a generation of men who feel slightly out of place in the modern post-Fordist economy, but not so in the pub. People of all backgrounds socialized together in the factories and the pubs.

In 1965, when the first Black barman, Linton Dixon, started pouring pints in the New Talbot Inn, Smethwick, it was such big news it made the local paper, nowadays the growth of the Asians owning and running local pubs passes without anyone even noticing. One reason is that the landlords have taken on establishments which were largely run down, and often plagued by violence. One comment often made is how much better they are now. Despite what we hear in the press about multiculturalism, one of the benefits of these mixed multicultural havens is that they are safe and welcoming, and of course they have cheap beer and food.

Inspired by the formal portraits in the local galleries, I worked with people who regularly popped into the pubs to create similar images. At the Ivy Bush, Smethwick, these were then printed onto pieces of aluminium; a homage to the local casting foundries where many Indians were employed. In the Four Ways, Rowley Regis, I created a lenticular, remembering the pub’s original landlord, the present one and his roots in India, and his son - the future. The lenticular reminds us that the pubs each have their own story, and the landlords, and the customers are part of that.

In 1964, at the height of the colour bars, Jagmohan Joshi, President of the Indian Workers Association (IWA) wrote to all the residents around Marshall Street, in Smethwick, quoting the words of the great Indian poet, Tagore (Gitanjali/8);

‘’The child who is decked with prince’s robes and who has jeweled chains around his neck loses all pleasure in his play; his dress hampers him at every step.

In fear that it may be frayed or stained with dust he keeps himself from the world and is afraid even to move.

Mother, it is no gain, thy bondage of finery, if it keeps one shut off from the healthful dust of the earth, if it robs one of the right of entrance to the great fair of common human life.”

These words are still relevant today. What is the role of the modern galleries if their fineries don’t speak to local communities? The ‘Desi pub’ and Creative Black Country are about creating inclusive spaces, even imaginary homelands, a place where Indian culture meets ‘Blighty’, bringing out the best in both.

Jagdish Patel www.jagdishpatel.com

Creative Black Country http://www.creativeblackcountry.co.uk

Everyone is used to seeing images of the “sites” of Tokyo but, for this piece, I have concentrated my attention on the suburb of Shimokitazawa which is particularly popular with young people. Basically, street photography, these images are intended to show both the people of the area and something of the environment.

A local guide describes the district thus;

“Shimokitazawa, commonly called “Shimokita,” is on the western side of Tokyo, and although just a small town, it is very popular among young people. In questionnaire surveys about where young people want to live, Shimokitazawa is always one of the top three responses. This is because there are many small theatre halls, live houses, bars and second-hand record shops, and this town is known as a trendsetting place for youth culture. With its many narrow alleys that are inaccessible to vehicles, you are given a real sense of adventure while exploring the town on foot, which is a real joy in and of itself.

When it comes to shopping, second-hand clothes shops and shops offering miscellaneous items from the 70s and old animation-themed toys are quite popular. The number of large-scale shops in the area has been increasing, but the nicest feature of this town is the many shops expressing the ingenuity of their young owners, such as those combining a cafe and a record shop or an outlet for small handmade items.”

I was initially drawn to the area because of a bookshop selling Japanese photobooks and Craft Beer but having seen the area I just had to go back another time to take the shots you see here and many others! The images were taken over a period of 4 hours in November 2016. It was a Sunday morning and less busy allowing a more open view of the surroundings. The shoppers come out in the afternoon when the narrow streets can http://www.robckershawphotography.com/

Going out for the day

The retail series forms part of my ‘Many in High Water’ project, documenting three aspects of modernity: insecurity, anxiety, and inequality.

Croydon - one of the largest commercial districts outside of Central London - provides an interesting case study of business insecurity. Many of the photographs were taken following the 2008 financial crisis, during the recession that tipped many retailers over the edge and forced them to close. Combined with the rise of internet shopping, the economic slowdown exposed their often precarious position. A fragility that affected the independent retailers of the secondary (and more run down) shopping malls, but also, more visibly (and more surprisingly) major outlets such as Jessops, HMV, Allders and BHS.

To quote the academic, Adam Greenfield:

“Again and again and again over recent years, the media has numbered the great British high street among those species that are teetering on the brink of extinction. You surely know the words to this song: the by-now conventional narrative has it that, between the seductions of suburban big-box stores, the convenience of online commerce and the sheer difficulties of getting around, the local retail district finds itself in a death spiral. Depending on where you happen to be standing, this can be hard to see from within London... But even in the capital, too many local hubs are struggling.” (The Guardian, 17/05/15).

I often find that a single image acts as a foundation for a project; providing early proof that it might work in practice. The retail series was founded on two photographs: the Lifeline Centre (sadly and ironically closed), and the recruitment agency window frozen in time from 2008 (conspicuously, and symbolically, bereft of jobs).

After documenting the impact of the financial crisis on the high street, I have returned to Croydon and been struck by the significant ‘churn’ of retail units. This turnover reflects ongoing retail insecurity, in the headwinds of internet shopping, rising costs and unpredictable consumer spending.

Going forward, it will be fascinating to see the impact of the new Westfield shopping complex (scheduled to open in 2022, following demolition of the existing Whitgift Centre). Regarding regeneration - Croydon was an epicentre of the 2011 riots - Whitgift is ‘being seen as the catalyst’ with ‘obvious economic benefits‘. This ‘destination shopping centre‘ will bring more visitors and jobs to Croydon, but the impact on existing retailers outside the complex is far less certain. Will there be a trickle-down effect boosting the wider economy, or will Westfield have a debilitating effect on existing retailers as shoppers head straight for the new centre?

http://www.thelongview.london/tlv/retail.html

I am not a great one for prints under the bed you know, I want an audience. It is important to me and becomes one of the delights of photography”.

So says David Hurn as we sit in his kitchen, discussing his Swaps exhibition at the Museum of Wales. The exhibition was made possible by his generous donation of 700 photographs from his personal collection (swaps with other photographers – their work for his) and includes works by leading 20th and 21st century photographers including Henri Cartier-Bresson, Eve Arnold, Sergio Larrain, Bill Brandt, Martine Franck, Bruce Davidson and Martin Parr, through to emerging photographers such as Bieke Depoorter, Clementine Schneidermann, and Newsha Tavakolian.

His collection is valued at £3.5m but he says, “It has nothing to do with money. When you collect, it is like collecting bus tickets, and it really is like having the definitive collection of bus tickets. If you are into collecting and you love doing it, the joy is getting another picture and that was the fun of it”.

Pictured below is one of the three most requested swaps from David Hurn. As he says, in one of his insightful and delightful comments that accompany the gallery’s display of prints, “the great thing about photography is that it is always an extension of the personality of the photographer “.

I ask how he selected the 80 images for inclusion into this first exhibition of photographs, (his donation to the museum being permanent, there will be now be a gallery dedicated to photography at the museum, a first for Wales). “My criteria is a gut criteria to a certain degree. I just like the pictures, so that is a part of it. I do confer with other photographers that I particularly like. It is also important to me that the photographs are by working photographers…they are not playing at it. Then I put those three things together and I don’t differentiate between anybody”.

It has taken three years to get the exhibition open, which has meant time away from shooting pictures, the thing he “enjoys immensely because by definition every day is different”. However his fierce desire to get photography “out to the public” means this time commitment has been worth his while. He thinks David Attenborough “an extraordinary man, almost the most influential person during my lifetime, because he has never lowered standards and has always got

out to everyone”. Attendance at the exhibition after only a few months has exceeded 33,000 and shows no sign of abating. Of this he says “The public like the idea of seeing variety and if you look at it in that light we (the museum) are as good as the Getty”.

He hopes the exhibition will reach the selfie generation. “I think it (the selfie) is a charming idea. It brings happiness to everybody… but I do think, with a bit of luck, it could be developed into something else”. He means people progressing to taking photographs of what they “see” because, in his words, “what photography does terribly well, is to point out how peculiar and how wonderful the world is. It allows you to see and point out to somebody else the things they might not have seen themselves”.

On the surfeit of images available via the Internet today, he says, in his typically upbeat fashion, “I try to look at it in a positive way. For the first time in history everybody likes photography and there has never been a time in history when everybody had a notebook and pencil” (commenting on everyone having a phone).

Our conversation turns to the practicalities of photography and as we take “dear diary” snaps (his words) of each other in his kitchen (his of me being infinitely superior to mine of him: pictured) he explains that he has always carried two cameras. In his film days they were Leicas. Now he shoots with the Fuji X Pro 2. One has a 28mm lens and the other a 50mm lens, so he can quickly swap between cameras without having to change lenses. Each camera has a coloured sticker on top (yellow and red) so that he can discretely glance down and select the right lens. He doesn’t shoot using the rear screen, preferring to place the viewfinder to his eye to compose. He has also customised each camera, adding a raised bump on the rear function button, again colour coded, so that he can easily fix the focus in advance of pressing the shutter. He chuckles at how “Fuji had a heart attack” when he showed them his handiwork!

He has always been his own man, turning down all permanent employment offers (including Life magazine!) because “you are doing a job that you hope to get paid for, but it is a job you enjoy so much that you don’t want an assignment as such, because an

assignment is a moral obligation to fit in, in some way, with what the person assigning the project will want”. “I do it (my job) as well as I can. I don’t bend from what I want to do”. The same is true of the swaps he has collected; always insisting on a particular photograph from his fellow photographers, which makes the Swaps collection at Cardiff incredibly personal.

On becoming a photographer he says “I was very lucky because I had no inkling that I wanted to be a photographer. I was in the army because I couldn’t do anything else (DH left school without qualifications due to his dyslexia) and I happened upon a photograph which literally changed my life, because it made me cry, and not only that, but in a way, to me, made me convinced the propaganda I was hearing (from the army) was… propaganda. I remember thinking quite seriously, anything that can, just by looking at it, emotionally can make you cry and at the same time kind of convince you that you know (something) is not true….that is pretty good. I quite liked that. I was lucky in that when I started I knew exactly what I wanted to do in photography (because of that revelation). Basically I just wanted to photograph people’s reactions to each other and their emotions. The other bit of luck that I think I have is that I think I have a really enhanced sense of design, pattern whatever you like to call it, geometry or composition”.

In 1973 his passion for photography, and desire to share photography with everyone, led to him forming, and teaching at, the School of Documentary Photography in Newport, Wales. He left when the diploma became a degree, believing that the course should lead to job opportunities: “My beef with education, is that it is so far removed from reality…and doesn’t lead to anything. Ultimately, to me, it seems that you need to be paid”.

He believes in the art and the science of photography, citing radiology as being a “most important (form of photography) because it really does save lives”. Touching on his experience with academic hierarchies he comments: “the people who talk most about these things (photography) take awfully bad pictures, and the most important picture in my life was taken up my arse with a camera, (he had cancer in 2000), you can’t dispute that, it saved my life, so ( laughing) if you want to talk hierarchies, well then a camera up the backside is number one!”

Does he believe anyone can take good photographs I ask: “So I mean the thing about photography is that you only have two controls. One is where do you stand and one is when do you press the button and the answer is, if you stand in the right place, and press the button at the right time, you have got a pretty good chance of having a picture, and the standing in the right place is all to do with getting your subject matter projecting in a design which is pleasing for people to look at. People like design, they feel safe with design”.

He is very involved with the gallery’s future, and in typical hands on fashion, he has been negotiating new swaps for the forthcoming year-long exhibition: Women in Focus - a two-part exhibition that explores the role of women in photography, both as producers and subjects of images. On his experience of trying to swap images with

women he chuckles “boy are they fussy”, but joking apart, he has always been a supporter of talent, regardless of gender, and a number of his female students are rightly included in the Swaps exhibition.

He has many ideas for the continued success of the gallery, including a regular lecture programme “delivered by the best people in the world” (the opening lectures, given by him and Martin Parr sold out and had to be relocated to a lecture room that could hold the 300 plus audience wanting to attend) but he is aware that continuing to reach an audience that is increasingly technology focused is challenging. “What is the web going to do in 4 or 5 years” he says. “Got a little bit of that (the web) in the gallery at the moment, but it is usually me on a screen talking about photographers, making funny jokes, but it really needs to get into this thing with your ipad you can do the photograph and then go further. I have no idea what that is but it has to go further”. A year ago he joined the Instagram community and publishes tips and recommended reading (and images from his own archive) on a regular basis ( davidhurnphoto).

“I am doing a thing with the museum (of Wales) at the moment” he says. “I am trying to set up a thing with schools, in which we run competitions, at which we have in the museum a little exhibition, maybe of ten pictures by different photographers, maybe Henri Cartier-Bresson or Bill Brandt or Lee Friedlander or whoever you like, and then we bring (the children) in and we say there is going to be a nice prize and we want each of you, independently, to decide which picture you like, which photographer, now go off and with your phone see if you can take a picture like that and I am arguing that maybe 10 per cent of those might actually do it. It might then start them saying this is different from photographing myself”.

He also has plenty of ideas for his own projects saying: “I am thinking about doing a whole thing about portraiture. I met a writer with the BBC and I have discovered that with the web the BBC goes out to 4M people. I like the idea of that sort of audience, so I am toying with the idea of doing the equivalent of almost another book. It takes a lot of time to do 100 portraits that is probably 150 days work but I thought I would just see how it goes”.

In his study he generously shows me the mind map he has created for his latest book explaining: “what this does is it gives me a very

loose framework, so that when I am in trouble I can fall back on it (for ideas)”. The book is about landscapes in Wales. Entitled “As It Is” he explains that “good traditional landscape photographers all think that you get up at 4.30 in the morning and you only bother to photograph for half an hour and I kept saying why the hell do you get up then? Nobody bothers to photograph at that time –your pictures are not true-nobody sees the world like that and they said oh it is so beautiful you know etc. and I said ok fine you get up I am not going to do that. I just want to photograph it as it is, and then I suddenly thought, well I have got a title. If I call it “As It Is” then if I go somewhere and it is pissing with rain I photograph it as it is! So that was my start”.

Reel Art Press published his latest book, Arizona Trips at the end of last year. Inspired by his twenty-year love affair with Arizona, it seeks, according to the dust jacket “to capture ordinary people in ordinary pursuits. From cheerleading to wild horse wrangling, Dolly Parton look-alike competitions, arm-wrestling contests and ladies only clubs with nearly nude male dancers.” Having just purchased my copy I can confirm it is classic Hurn and, to use his words about one of his students “You can’t take that sort of picture unless you are really involved with the people you are photographing”.

The Swaps exhibition is a unique, inspiring, and very personal exhibition, collected by one of Britain’s most influential reportage photographers trading his own prints with many of the world’s leading photographers. It has inspired Magnum Photos (in partnership with theprintspace) to set up a project giving the global photography community the opportunity to participate and maybe swap a print with David Hurn as well as each other (see Magnum’s website for details).

My advice: visit the Museum of Wales now for inspiration.

The last word has to go to David Hurn, as he says of the lead image for the exhibition: “Elliott’s picture of the bird and the tap I particularly like - it’s just a beautifully observed, humorous picture. It would be nothing if it were set up. But part of its enormous appeal is the fact that it’s taken by Elliott - you know it was just “seen”. It’s very elegant, beautifully balanced and composed”.

Interview by Valerie Mather

USA. Florida Keys. 1968.© Elliott Erwitt/Magnum Photos

The Documentary Group focuses on photography which chronicles everyday life in the broadest possible way, as well as topical events and photography which preserves the present for the future, through both individual images and documentary ‘stories’. It is typically found in professional photojournalism, real life reportage, but importantly for us it is an amateur, artistic, or academic pursuit. The photographer attempts to produce truthful, objective, and usually candid photography of a particular subject, often of people.

Members form a dynamic and diverse group of photographers globally who share a common interest in documentary and street photography. We welcome photographers of all skill levels and offer members a diverse programme of workshops, photoshoots, longerterm projects, a prestigious Documentary Photographer of the Year (DPoTY) competition, exhibitions, and a quarterly online journal “Decisive Moment’. In addition to our AGM and members gettogether we have an autumn prize-giving for the DPoTY incorporating a members social day.

Some longer-term collaborative projects are in the pipeline for the future. Additionally, we have an active Flickr group and Facebook page.

Overseas members pay £5 per annum for Group membership rather than the £15 paid by UK based members.

The Documentary Group is always keen to expand its activities and relies on ideas and volunteer input from its members.

If you’re not a member come and join us see: http://www.rps.org/special-interest-groups/ documentary/about/dvj-membership

Find us on the RPS website at: http://www.rps.org/special-interest-groups/documentary

www.rps.org/special-interest-groups/documentary

Designed, Edited & Published by Jhy Turley ARPS www.jhyturley.com