18 minute read

Greenham and

Greenham and Crookham Commons - Part 1

A photographic study documenting some legacies from the airfield’s past through to the present day. ROBERT C CARPENTER LRPS

Ihave lived in the Newbury area for nearly 50 years and, for the first 30 years or so, the Greenham and Crookham Commons (Greenham Common) were always imposing and mysterious areas of land on the south side of the town. This mystery was only alleviated on occasional airbase Open Days and then the official opening of the common in 2000. Greenham Common, and in particular the airbase, has undergone a series of dramatic changes over its operational life and a short history is offered to help to illustrate the effects, geographical implications and legacies of some of these changes. More detailed presentations of the history of the airbase can be found in the references at the end of this article. Greenham Common’s more recent changes began in 1941, when the Air Ministry requisitioned the land to build an airfield and construction of the initial airfield runway started early in 1942. It was to be an RAF Bomber Command Operational Training Unit with the main runway 5,988 feet in length, two secondary runways and many hard-standing dispersal areas. Accommodation, bomb storage sites and other installations were widely spaced over the surrounding local countryside. A period of expansion followed with the 51st Troop Carrier wing arriving from America in September 1942 to take part in Operation Torch and in October 1943 Greenham Common became USAAF (US Army Air Force) Station 486 and was handed over to the 9th Air Force. Part of the planning for D Day operations, in mid 1943, required the construction of the Waco and later Horsa gliders. This also required a significant effort to build accommodation blocks, workshops and associated utilities. March 1944 marked the arrival of the 438th

Troop Carrier Group flying C-47 Skytrains (Dakotas). New infrastructure was developed to support these larger aircraft and steel marshalling yards were constructed at either ends of the main runway in preparation for the forthcoming glider movements. On the evening of June 5th 1944 General Eisenhower addressed 55,000 men of the 101st Airborne (the Screaming Eagles) on Hungerford Common and later gave his famous “The eyes of the world are upon you ...” speech at Greenham Common. Shortly before midnight, the first C-47 (named “That’s All, Folks!) took off bound for enemy territory in Normandy on Operation Overlord. In two days, 1,662 aircraft and 512 gliders were deployed and a total of 13,000 paratroopers were dropped and 4,000 landed by glider. After 1946 the airfield fell into disrepair but was totally rebuilt and redeveloped in the early 1950s with a longer, stronger runway to accommodate B-47s and ultimately B-52 strategic bombers. A new Control Tower was built on the north side of the airbase. The airbase was operational again from 1953 and, between 1956 and 1964, as part of a Reflex Alert Scheme with nuclear armed B47s and supporting KC97 tanker aircraft. The Americans left in 1964 but returned again in 1967 to take on some NATO commitments. The airbase was host to 8 Air Tattoos between 1973 and 1983 with the last show being the world’s largest military air show at the time. In 1979 the decision was made by NATO to site nuclear cruise missiles in Britain and other European countries and in 1980 the Defence Secretary announced that Greenham Common would house 96 nuclear armed Tomahawk cruise missiles. This marked the start of a major building programme to support these missile deployments. Especially hardened steel, sand and concrete shelters were constructed to house the missile transporters and the GAMA site (Ground Launched Cruise Missile Alert and Maintenance Area) was born. In 1981 a group called “Women for Life on Earth” marched from Cardiff to Greenham Common and set up the first Peace Camp. Many protests occurred over the next few years including encircling the base and the 1983 human chain involving 70,000 protesters linking hands from Greenham Common to the Ordnance factory at Burghfield. Nine Peace camps were formed in total and the final camp was not disbanded until 2000. In December 1987, the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty was signed and the final cruise missiles left the Base in 1991 followed by the remaining USAF personnel in September 1992. In the mid 1990s the runway and taxiways were broken up and removed from the airbase, a Business Park was established and planning commenced to return the open land to the people of Newbury. This was achieved in April 2000 and this area (and the airfield) is now part of a nature reserve managed by the Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Wildlife Trust (BBOWT) Through this photograph study I am illustrating historical events in living memory by photographing the remaining structures, buildings, landscapes or other evidence. The three articles cover the following broad timescales: • The wartime and Cold War years 1941- 1980s • Cruise missiles and the Peace camps 1980 - 1991 • The Regeneration of the Common 1992 to date

The wartime and Cold War years 1941 – 1980s.

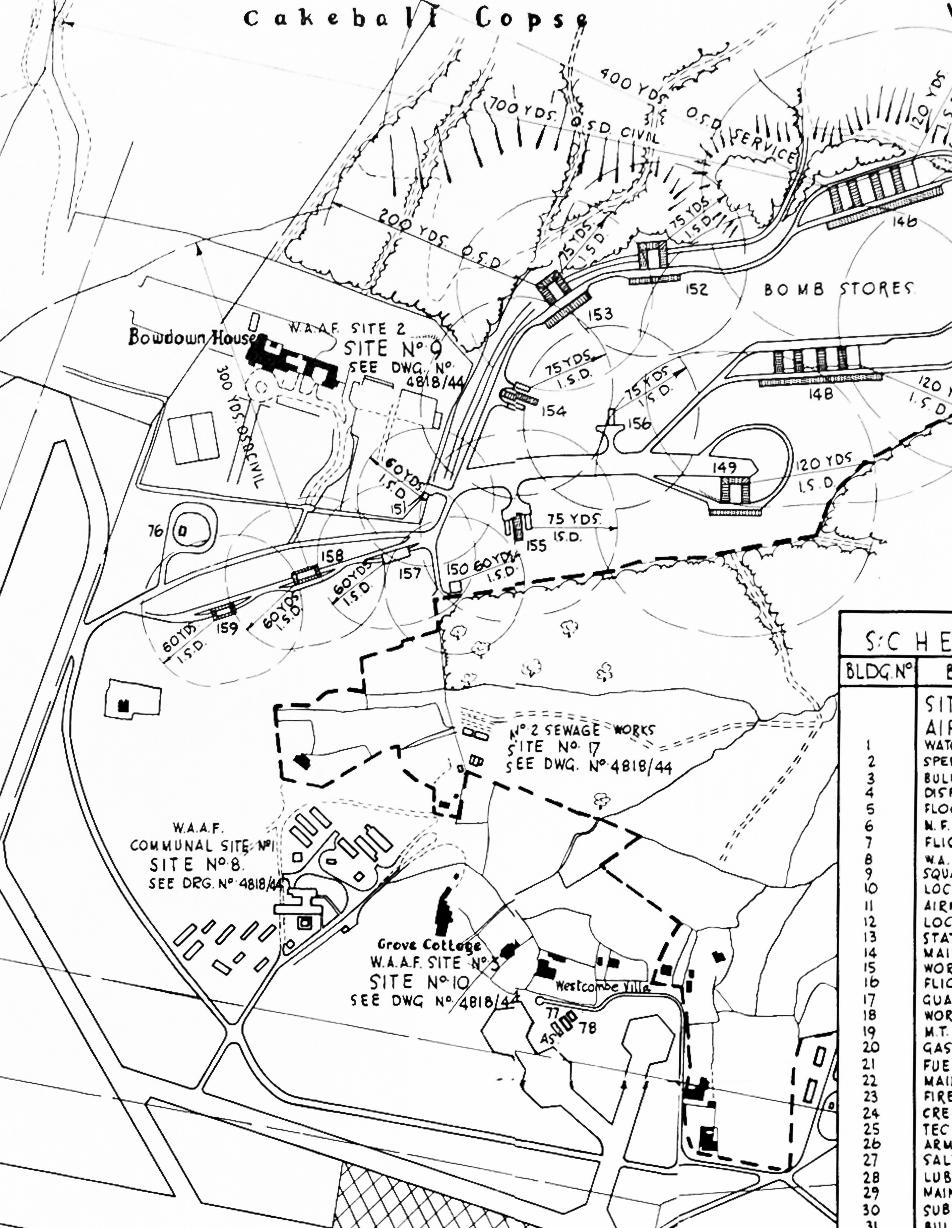

Figure 1 shows a 1944 map of the Class A airfield with its 3 runways and dispersal areas. The bomb stores to the North East and the glider marshalling areas at either end of the main runway can be clearly seen. Examples of the remains of some of the buildings are illustrated; Bomb store building 148, Figure 3, Pyro store building 156, Figure 4 and location of Fuzing Point building 159, Figure 5. Because of the change of use of the airfield in 1943, it is believed that this “bomb stores” site was never used for the purpose originally intended. Two local houses played significant roles in the war years. Bowdown House can be seen to the western area of the “bomb stores” (north east of the airfield). This house was built in the Lutyens style in 1911 for the Lang family and Figure 6 shows a picture of the house taken in 2018. When the Germans invaded Norway in 1940, King Haaken VII and other members of the Norwegian Royal Family escaped and, after a short spell at Buckingham Palace, were invited to stay at Bowdown house by Captain Robert Dormer. Many other distinguished guests were entertained here including King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, the Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, Madame Chiang Kai-shek and King Peter of Yugoslavia. In 1942 the Air Ministry requisitioned Bowdown House as the HQ for the USAAF 51st Troop Carrier Wing and the Dormer household moved to Windsor for the remainder of the war. To the North West of the runway centre can be found Greenham Lodge. This was built for Lord Baxendale (the Lord of the Manor of Greenham) and completed in 1881. It remained in the family until it was sold in 1938 to Newbury Council. In 1943, the house became the Divisional HQ for the USAAF 101st Airborne Division (the Screaming Eagles). The officers were billeted in the house and some enlisted men lived in tents in the grounds.

Figure 2. Map showing details of the “bomb stores” site. The mix of buildings entitled “bomb”, “incendiary” and “pyro” stores plus “fuzing point” buildings, linked by concrete roadways, is still clearly visible on the ground although heavily damaged and overgrown.

Figure 3 Bomb store building 148

Figure 4. Pyro store building 156

Figure 6. Bowdown House

Just before midnight on the evening of June 5th 1944, from the rear of Greenham Lodge, General Eisenhower watched the mass take off of Dakotas. He saw 81 Dakotas take off at 11 second intervals carrying ~1400 paratroopers to the area of Utah beach on the Cherbourg Peninsula. Figure 7 shows a view of the rear of the house. In 1951 the Lodge became a Club for USAF Officers stationed at Greenham Common and it continued in this role until the closure of the Station in 1992. In 1996, The Mary Hare Foundation relocated Mill Hall Oral School for deaf children from Sussex to Greenham Lodge which was subsequently renamed Mill Hall. Massive structural and geographical changes have taken place over the ~50 years of operations at Greenham Common. Following the original airfield construction in 1941, the Americans carried out extensive restructuring works in the 1950’s. These included a complete new 10,000 feet runway (12,000 feet with later extensions), taxiways and hard standing areas, a new technical and domestic site, demolition of houses and a Pub and the diversion of a main road. A new Control Tower was built and this was of a standard design of a 2 storey tower surmounted by a roof mounted visual control room. In the 1980s, the arrival of cruise missiles required the construction of the high security Cruise Missile GAMA site. The 1950s Control Tower, following some refurbishment in the 1980’s, remained operational until the Americans left in 1992. The Tower was then closed up, shuttered and fenced off from the common and it remained in this state for around 25 years.

The plan to remove the runways in the late 1990’s led to a five year regeneration project to break up, crush and remove over 1 million tonnes of asphalt and concrete. Therefore, it is no real surprise that limited evidence remains of the original wartime airbase! Recent access to the Control Tower has allowed a view of one of the remaining Cold War era hangers. These hangers have been refurbished and now exist within secure areas of the Business Park. Figure 9 shows a photograph taken from the Control Tower across the previous runway area of the common in a southerly direction. The Base Chapel was another much used building which is also now within the Business Park. It was a multi-denominational place of worship built in the late 1950’s and, after refurbishment over the years, it has now been reborn as the Old Chapel Textile Centre and National Needlework Archive. The Cold War operational airfield had 21underground Petroleum Oil and Lubricants fuel stations (POLs) located around its perimeter to provide fuel to the individual hard standing areas. These were connected by pipelines to the National Strategic Fuel Line at the eastern end of the airbase. These fuel tanks had a total storage capacity for 8 million gallons of aviation fuel. The tanks were either cylindrical steel structures or cast concrete cylinders with internal, reinforcing steel props. The vast majority of these POLs were removed and disposed of in the regeneration project; a single remaining concrete tank with associated pipe work is situated on the eastern edge of the airbase and is shown in Figure 11. During the regeneration project, many of the reinforcing steel props from the inside of these concrete tanks were relocated around the common and have variously been described as weather stations or fire-beater stands. An example of one of

these is shown in Figure 12. Located in a quiet corner of the common can be found one of the few remaining, rusting steel fuel tanks. This location also displays a fire hydrant and many of these were also relocated and positioned around the landscape – however, these are not connected to water supplies! Also in this view is a Naval paravane but no information is available as to how or why it came to be here.

Figure 8. A view of the closed and fenced Control Tower taken in 2010. Figure 12. Reinforcing steel prop adjacent to the original airfield Windsock mast.

Figure 9. View of one of the 1950’s Cold War hangers.

Figure 13. One of the few remaining steel fuel tanks.

Figure 14. One of the many ponds located around the common. Figure 15. Building believed to contain remains of an artesian well, pipe work and water treatment plant.

When walking around the common, a number of ponds of various sizes and shapes are part of the landscape. Some of these were created during the regeneration project and others are the result of the removal of fuel tanks of various shapes and sizes. These are attractive features on a lowland heath common and are home to a wide variety of wildlife.

A number of Cold War buildings still exist on the common but it can be quite difficult to identify the original purpose of these. Figure 15 shows what is believed to be the structure surrounding an artesian well. The building contains pumps and distribution pipe work and the sign on the doorway refers to emergency action to be taken after a chlorine gas leak. Another Cold War building close by is now a haven for bats, but in its previous life was believed to be used for gas exposure training.

Quite close to Building 280 is the naked, ferrous skeleton of the Fire Plane which is a reduced scale mock up of a C130 Hercules aircraft. This was installed in the 1980s and was used for fire fighting training by airfield fire crews and the Newbury fire brigade. It was fitted with dummy seats and passengers prior to training exercises and was linked with a pipeline allowing the fuselage to be sprayed with aviation fuel. The structure is located in a pond area presumably to contain water/foam and aviation fuel

Figure 16. Building 280 which is now a haven for bats.

Figure 17. The Fire Plane in its circular, fenced compound.

Figure 19. Remains of 1950s security fencing. Figure 20. Taken from the remaining central cross from the 1950s runway layout looking west along the runway path.

The majority of the 1950s airfield security fencing was removed in the early 1990s after the Americans left and the regeneration of the common began. However, a short length of fencing was left as a reminder of the site’s previous existence.

During the 5 year programme to remove the 4 feet thick 1950s concrete runways, a decision was made to retain the central cross over taxi way. This is the only remaining evidence of what was once one of the longest runways in Europe.

Future articles will continue to explore the legacies of the cruise missile era and then continue to illustrate Greenham Common in the present day. Bibliography.

Sayers, J.J. (2006) In defense of freedom: a history of RAF Greenham Common. Cooper, E. Swords and ploughshares; the transformation of Greenham Common. In: Kippin, J, Cooper, E &Hipperson, S. Cold War Pastoral. Brooks, R.J. (2014) Berkshire airfields in the second world war. Countryside Books.

Personal communications

Kempe, Andy. A not so common Common. Emeritus Professor, University of Reading. Jonathan Sayers Peter Evans Mike Hall

Pam Hart I am grateful for the advice and information many people gave during the preparation of this work. However, all mistakes are entirely mine.

Photographic details

Canon eos 7D, Canon EF 24-105 mm lens, Sigma 18-250 mm lens. Canon eos R, Canon RF 24-105 mm lens, Canon RF 24-240 mm lens. Images processed in Lightroom.

ROBERT C CARPENTER LRPS

PLACES TO VISIT 300 Years of Military Engineering

Britain’s military museums are unique and invaluable treasure houses of the country’s military heritage – from the small but intensely proud museums representing their local county regiments, to the major national institutions recording the history and traditions of particular arms. Here we look at a museum designated as having “collections of national and international significance” – The Royal Engineers Museum in Kent. R. KEITH EVANS FRPS

Like its ‘designated’ counterpart the Royal Artillery Firepower museum in London, the Royal Engineers Museum – located adjacent to The Royal School of Military Engineering in Chatham – covers more than 300 years of military achievement. Both Corps were founded in 1716; but the Royal Engineers antecedents’ go back to the Norman Conquest, first as The Kings’ Engineers and later as engineer officers of the Board of Ordnance. ‘Ordnance Trains’ of engineers and artillerymen would accompany the armies of the day, until in 1716 the two roles were separated, forming the Royal Regiment of Artillery and The Corps of Royal Engineers. Into the latter were incorporated the Royal Sappers and Miners in 1855. So the 500,000-plus objects in the Royal Engineers Museum encompass more than three centuries of technical development in helping Britain’s armies move and fight, from military architecture and siegecraft to flying, diving, mapping and combat engineering.

Artefacts large and small

Exhibits range from medals (including 48 Victoria Crosses) to bridge structures, aircraft, torpedoes and 50-ton specialised tanks and armoured fighting vehicles. You will find the Duke of Wellington’s battlefield map of Waterloo; the first successful underwater guided weapon – Louis Brennan’s torpedo of 1877; weapons from the Anglo-Zulu war of 1879; and a broad range of more modern equipment such as the Bailey Bridge and its successors, and tracked bridge-laying and mineclearing vehicles based on then-current tanks. Some of the Royal Engineers’ functions were handed over at various times to other branches of the armed forces: undersea mining, for example, to the Royal Navy in 1905, flying and ballooning to the Royal Flying Corps on its formation in 1912, and telegraphy to the new Royal Corps of Signals in 1920. All these early R.E. activities are recalled in the museum collections. The major part of the collections is housed in and around the Ravelin Building, constructed and fitted out in 1905 as the Royal Engineers School of Electrical Engineering (a ravelin is a vee-shaped outwork of 16-17th century fortifications). It became a museum in 1987 and was ‘Designated’ in 1998.

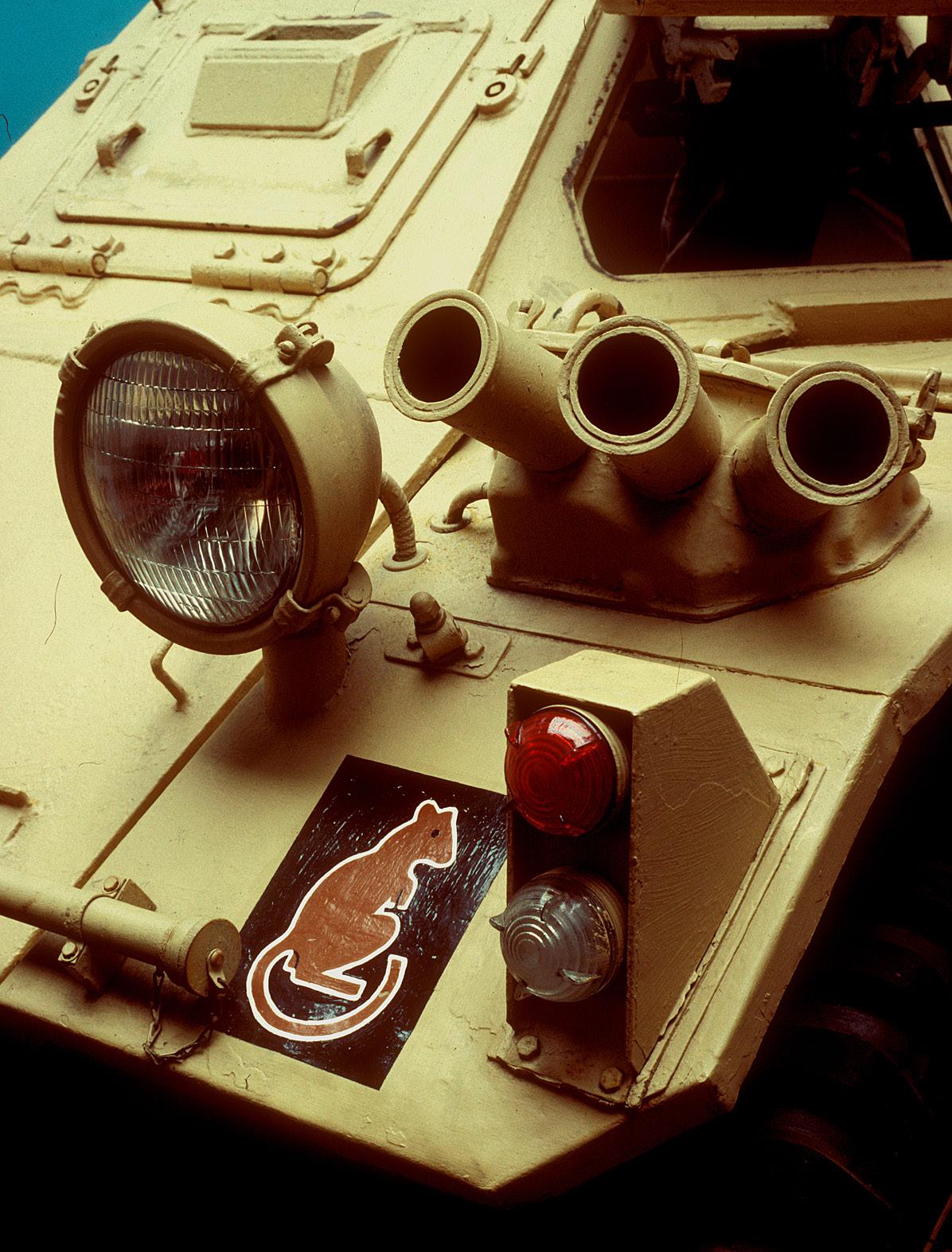

Armoured Personnel Carrier used by RE units in North Africa, 1942-43.

Uniform of Colonel George Landman RE, 1817. Officer’s dress helmet from 2nd Afghan War, 1878.

The Multipurpose Engineering Tank, the Trojan AVRE is here handling pipe fascine used to cross anti-tank ditches. This example has seen service in Afghanistan.

Final version of the Brennan Torpedo, described in the text below.

The Titan AVLB (bridge-launching AV) can carry and hydraulically launch a three-section 26m bridge. The Ravelin Building is in the background.

Brennan’s Torpedo and Hobart’s Funnies

The world’s first underwater ‘guided missile’, a shore-based torpedo for coastal defence, was the brainchild of Louis Brennan. Born in Ireland in 1852, Brennan and his family moved to Australia in 1861, and Louis studied engineering at Melbourne University. At the age of 22 he received a Victorian Government grant to design a ‘steerable’ torpedo; his patent for this was quickly purchased by the British War Office, and in 1877, now as Superintendent of the new Brennan Torpedo Factory in Chatham, he oversaw construction of these missiles, made and operated exclusively by the Royal Engineers and in service from 1890 to 1906 at eight key military coastal sites. The torpedo was some 30ft long and travelled 12ft below the sea surface at a speed of 27kt (31mph) for about one mile. It was controlled by an operator on shore; one such launch site and its two ramps can still be seen at Cliffe Fort, on the Hoo peninsula in Kent, and one remaining example of the torpedo is at the Royal Engineers Museum. Major General Sir Percy Hobart, born in 1885, was commissioned into the Royal Engineers in 1902 and in World War 1 gained the Military Cross and a DSO. Transferring later into the Royal Tank Corps, he formed and commanded the 7th Armoured Division (the Desert Rats) in 1940, and three years later was charged by Winston Churchill with forming and commanding the 79th Armoured Division, and in evolving the specialised armour needed to breach the German coastal defences in Normandy on D-Day, and subsequently throughout the drive for Berlin. His innovations included the flail-equipped Scorpion tank, designed for the task of mine clearing, the Churchill Assault Vehicle Royal Engineers (AVRE), the amphibious ‘swimming’ Sherman tank, flamethrowers and wire-mesh carpet layers again based on the ubiquitous Churchill and other tanks – all of these were known as ‘Hobart’s Funnies’, and had a major influence on operations on the Western Front. Several are on display in the museum’s outdoor Vehicle Park. Though closed during the first months of the Covid19 epidemic, the Museum re-opened in August and visits can now be pre-booked for specific dates and times. Their website is located at https://www.re-museum.co.uk/. Pictured on page 3 is the commemorative sword presented in 1898 to Major General (Lord) Kitchener in recognition of his commanding the Anglo-Egyptian Army in the Sudan.