6 minute read

A SUCCESSFUL F PANEL

The RPS Benelux Chapter DISTICTIONS

© Mick Yates FRPS

Between 1975 and 1979 the Khmer Rouge

killed an estimated 2 million people in their attempt to create an agrarian society cleansed of urban Intelligentsia. Forty years later the Genocide's devastating impact on Cambodian society still resonates, and personal stories remain untold.

Our collective memory is driven by the 'mug shots' of victims at the Tuol Sleng torture facility and the skulls from the Choeung Ek Killing Fields. Those accused were meticulously photographed, tortured until they confessed. and then killed.

The camera was in effect their executioner.

Yet there are almost 20,000 mainly unmarked grave sites across the forests. The story of the Genocide is today buried in an anonymous landscape.

Despite its power to judge, the camera also has limitations in telling such complex stories.

How can we condense Genocide into a short

series of contemporary images? How do we show bodies not there? How do we best communicate intense, horrific stories of survivors without falling foul of triteness and trope? And most importantly, how can we get an audience to 'look again' at events long past?

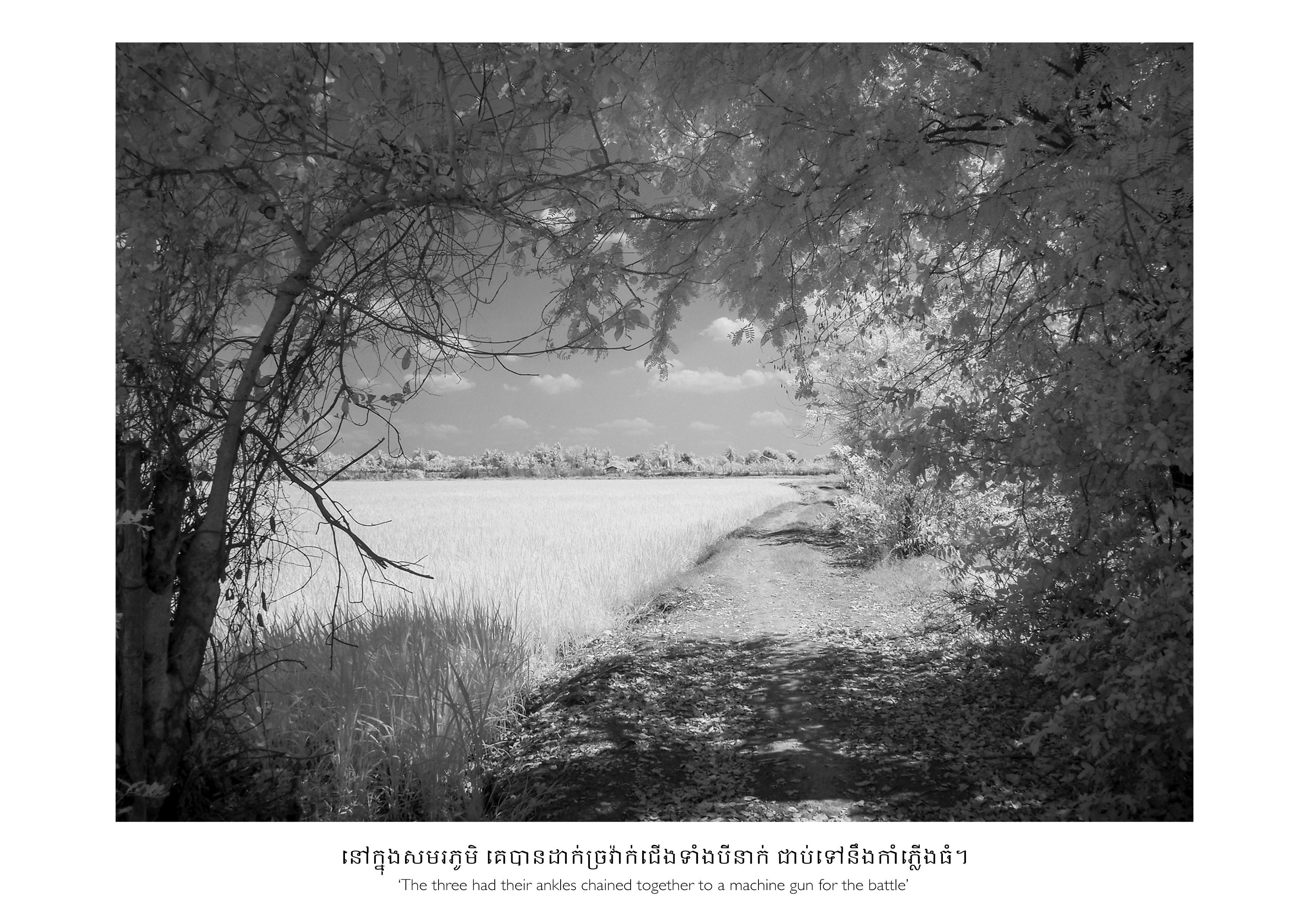

UNFINISHED STORIES tells the personal accounts of Cambodian friends who have never

spoken out before. II combines a photograph which illustrates the strange phenomenology of the now often beautiful landscape with a quotation from their traumatic experience.

The aim is to hold the viewer's attention for quiet study, in a manner which has a long photographic pedigree.

The Khmer language Is used to respect the storyteller whilst also anchoring the geographic location of communal suffering. English aids the Western audience.

This series, in chronological order of events, combines present-day photographs of that historical landscape of death, made real with narratives of personal pain in that same landscape.

285 Words

Fellowship presentation plan - during the assessment, the name and membership number are in black (anonymized)

© Mick Yates FRPS

© Mick Yates FRPS

© Mick Yates FRPS

© Mick Yates FRPS

© Mick Yates FRPS

© Mick Yates FRPS

© Mick Yates FRPS

ABOUT 2 MILLION CAUSALITIES

Prince Sihanouk tried to keep Cambodia neutral, but he allowed Vietnamese supply lines to cross the country during the Vietnam War. US bombs killed tens of thousands of innocent

Cambodians in a vain effort to disrupt these trails. This helped push the population towards the Khmer Rouge, which was a tragic error.

The Genocide was stopped in 1979 by the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia, although their army only left the country in 1989. Still, very few of the original Khmer Rouge leadership were brought to justice. The UN backed tribunal only opened investigations in 2007.

From a personal perspective, my wife Ingrid and I have a fairly long-standing relationship with Cambodia and its people. In 1994 we first visited as tourists with our then young children. Some parts of the country still saw fighting between the Royal Cambodian Army and the Khmer Rouge. In fact, we heard shell fire when we were visiting the famous Angkor Wat temple on a lovely blue-sky day. This prompted our interest in the country and in researching its history.

Until the death of Pol Pot in 1998, parts of the country remained under Khmer Rouge control. Reconciliation with the rest of Cambodia only started then. In 1999, Ingrid and I founded a primary school program in the northern Reconciliation Areas, along the border with Thailand. Working in collaboration with Save the Children, the Ministry of Education and even some ex-Khmer Rouge, the partnership helped rebuild the local education system. Keo Sarath and Beng Simeth led the programs, and these two men feature in my subsequent documentary photography.

I agreed with our Cambodian friends on a rough project outline and an intensive series of visits to both record their stories (some with video) and experiment with different photographic approaches. Almost from the first of these visits, it became clear that, despite its power to judge, the camera also has limitations in telling complex stories. I was also acutely aware of ethical considerations in portraying Genocide, and I did not want to fall into the traps and tropes of ‘dark tourism’. At every stage the effort was collaborative with our friends and various

Cambodian experts and institutions.

I settled on the idea of photographing today’s landscape as the visual centre of the work and linking back to the rather anonymous history of the Genocide. These landscapes included sites of atrocities which are rarely visited today. Initial work using portraits or other more traditional documentary techniques just wasn’t creatively ‘cutting through’.

I CHOSE INFRARED FOR ITS POWER

After much experimentation, I chose infrared for its power to show ‘hidden’ detail in the forest, whilst actually at first looking like ‘traditional’ black and white. I wanted intrigue and not exaggeration.

During the MA, I also researched the use of text with photographs to overcome the camera’s story-telling limitations. In my images, the rather beautiful Khmer script is used to respect the storyteller whilst also anchoring the geographic location of communal suffering. A small English sub-title aids the non-Cambodian audience.

The resultant series, in chronological order of events, combines present-day photographs of an historical landscape of death, made real with narratives of personal pain in that same landscape.

I also published a book titled Unfinished Stories; From Genocide to Hope. This book is dedicated to our friends and tells their stories in full. It is not a pure photobook but is more an illustrated history of the Genocide made real with personal biographies. Learning from previous mistakes, I sought advice via the RPS online system. Originally, I was thinking of applying in the Documentary category, but discussions lead to a decision to apply in Contemporary given the complexity of the story and the mix of photographs and text.

EXCELLENT ADVICE

I would like to single out the excellent advice (and on-point questioning) from Richard Brayshaw FRPS which in particular helped better connect the Statement of Intent to the work. In my mind, getting that connection right is key to the Fellowship process.

I was honoured to receive the Fellowship on April 22nd. I admit that I was rather taken aback by the positive comments that the work garnered, both at the assessment and subsequently on social media.

Unfinished Stories; From Genocide to Hope Photography by Mick Yates FRPS

Foreword by Dr. Hang Chuon Naron, Minister of Education, Youth and Sport, Cambodia

Designed by Victoria Yates

Prices £35 (UK), £40 (Europe) and £46 (rest of the world) including post and packing

Hardback with dust jacket 27,4 x 20,5 cm, 106 pages UK ISBN: 978-1-9163092-0-3