10 minute read

Cornwall: Then and Now by Andrew Gasson ARPS

Cornwall: Then and now

In 1851, Wilkie Collins – Victorian author of The Moonstone, The Woman in White and numerous other novels - published Rambles Beyond Railways: or notes in Cornwall taken a-foot. This described his walking tour of Cornwall the previous year and included twelve lithographs by his travelling companion, the young artist Henry Brandling.

In his introduction, Collins wrote “On considering where we should go, as pedestrians anxious to walk where fewest strangers had walked before, we found ourselves fairly limited to a choice between Cornwall and Kamchatka - we were patriotic, and selected the former.”

In the absence of the railway to Cornwall in 1850 – hence the title of the book - the walking tour for the two travellers started in the east with a boat trip from Plymouth via Saltash to St Germans. Their journey then took a route along the south coast of Cornwall to Land’s End, with excursions inland, returning along the northern coast to end near Tintagel.

On recent visits to Cornwall, I have been attempting to reproduce photographically Brandling’s twelve scenes as they now appear, compared with the early 1850s. Using Lightroom and Silver Efex, images have been converted to black and white and toned to match as far as possible the colouring of the original lithographs. Most of the images were taken with a Nikon D810 using 28-300mm or 18-35mm lenses.

Six pairs of images were included in the Landscape Group’s Newsletter for December 2019. It is now possible to reproduce all twelve, presented in the correct order to follow Collins’s original route. Quotations in the text with one exception are taken from the first edition of Rambles.

The old adage that ‘the camera never lies’ has been superseded by the more recent notion that anything is possible with modern digital editing. The photographic images are true to the original scenes with no digital additions or subtractions. I hope, when compared to the original lithographs, they will demonstrate that artists – even in the 1850s - employ as much, if not more, licence than photographers.

St Germans

Collins and Brandling arrived at St Germans where Brandling produced his first illustration. The view now is remarkably similar to that of 1851. The 13th century Norman church is Grade 1 listed, still standing but no longer covered with foliage.

The main house looks very much the same and the tree on the left is perhaps also the original. The viewpoint is now situated on the private Port Eliot estate, requiring permission to enter, and was also chosen to obscure parked cars to the left of the image.

On the other hand, alas, there are no longer strolling families with bonnets and top-hats.

Nikon D810; 28-300; 28 mm; 1/500 at f8 ISO 800

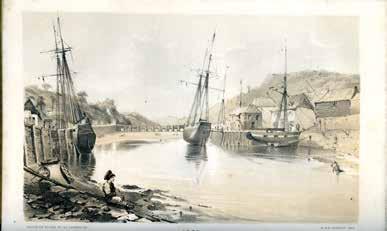

Looe

A ten mile walk from St Germans is Looe which was, and still is, a “fishing town on the south coast of Cornwall,” then with a population of about 1400. Collins had anticipated “a little sea-shore paradise” and described Looe as “one of the prettiest places in England.” He stayed at the Ship Inn which is still in existence. The original stone bridge which Brandling drew dated back to 1436, was 384 feet long and consisted of fifteen arches. It was replaced in 1853, three years after Collins’s visit, and still separates East and West Looe. In season, the town is now a very busy tourist destination but small fishing and pleasure boats do still abound. Apart from trying to match the viewpoint, another challenge was to find the tide in a similar state to the original scene.

Nikon D810; 28-300; 78 mm; 1/1600 at f5.6 ISO 400

The Cheese-Wring

The travellers followed their visit to Looe by turning inland to Bodmin Moor. Here they visited the Cheese-Wring set above a megalithic site known as the Hurlers. It is a precarious-looking inverted triangle of stones, both then and now “visible a mile and a half away, on the summit of a steep hill ….. the wildest and most wondrous of all the wild and wondrous structures in the rock architecture of the scene.” Take your choice whether you believe it to be a Druid temple or a natural rock formation. Brandling’s picture makes it appear much more rugged in Collins’s day and at some more recent time it has been stabilised with the additional stones on the left-hand side. Fortuitously, a modern tourist substitutes for the Victorian gentleman in the original.

Nikon D810; 28-300; 52 mm; 1/1000 at f9 ISO 800

Loo-Pool (Loe Bar)

The tour continued inland until it reached the Loo-Pool (Collins’s spelling) on the coast. Despite the similarity in name, it is nowhere near the fishing village but about 60 miles further west, a short distance from Helston near Mount’s Bay. It is Cornwall’s largest freshwater lake (the Loe), about two miles long, separated from the sea by the sand and shingle bank of Loe Bar. Brandling’s viewpoint is taken from the eastern side at the south of the lake. There is now no sign of either Brandling’s tree or the cottage on the opposite headland. Long gone, if they ever existed, although Photoshop could no doubt resurrect them. The Loe, according to Tennyson and legend, is possibly the lake into which Excalibur was cast after the death of Arthur.

Nikon D810, 18-35 mm, 18mm1/640 at f11 ISO 250

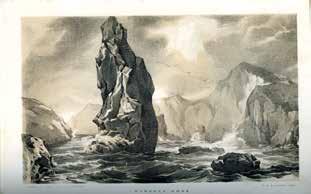

Kynance Cove

Collins and Brandling continued further west to the Lizard, England’s most southerly point, and then took a two mile walk along vertiginous cliffs to reach Kynance Cove, “the place at which the coast scenery of the Lizard district arrives at its climax of grandeur…..unrivalled in Cornwall; perhaps, unrivalled anywhere.”

Brandling’s lithograph shows Steeple Rock, slightly more attenuated than in real life, surrounded by waves – a good example of artistic licence. Kynance Cove is a photographer’s delight to visit with dramatic rocks and caves to explore. The original as pictured, however, is impossible to replicate. The viewpoint can be reached only at low tide since, at all other times, this portion of the beach is completely submerged.

Nikon D810, 18-35 mm, 18mm1/1000 at f8 ISO 320

St. Michael’s Mount

Situated opposite the small town of Marazion on Mount’s Bay, St Michael’s Mount is now a National Trust property. Lord St Levan of the St Aubyn family retains a 999-year lease to live in the castle and open the historic rooms to the public. The Mount is approached either by boat or along the famous causeway at low tide.

The lithograph of St Michael’s Mount is another case where it did not prove feasible to replicate the exact view photographically. Irrespective of the more recent foreground buildings and preponderance of trees, Brandling’s viewpoint is impossible to achieve. The smaller photograph has been flipped horizontally to match the original as closely as possible. The artist’s version is almost a mirror image of the true scene; the larger photograph shows the reallife view.

Nikon D810; 28-300; 70 mm; 1/400 at f11 ISO 400 Image flipped horizontal

Unreversed image from Camera

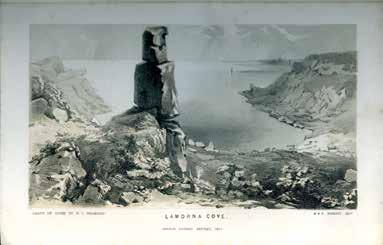

Lamorna Cove

Lamorna Cove is situated beyond St Michael’s Mount on the western side of Mount’s Bay, about four miles from Penzance. In the twentieth century, Lamorna became the home of the surrealist artist, writer and occultist, Ithell Colquhoun. The view today, with its quay and cottages, is completely different from Collins’s time. The centre-piece obelisk of Brandling’s illustration was either pure artistic licence or subsequently removed. Lamorna became the site of extensive granite quarrying between 1849, the year before Collins’s visit, and 1911. Possibly the obelisk was the granite sent to London for the 1851 Great Exhibition or even part of that used to form the Thames Embankment.

Nikon Z7; 24-70; 24 mm; 1/400 at f11 ISO 200

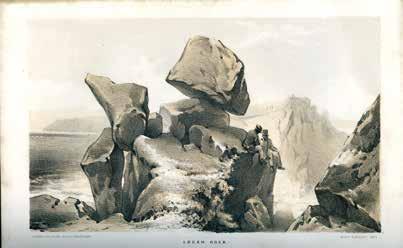

The Logan Rock

The term logan signifies a pivoted rock as a result of natural erosion. The Logan Rock is situated on the Cornish coast near the village of Treen about five miles from Lamorna. “This farfamed rock rises on the top of a bold promontory of granite, jutting far out in to the sea ….. When you reach the Loggan-Stone, after some little climbing up perilous-looking places, you see a solid, irregular mass of granite, which is computed to weigh eighty-five tons, resting by its centre only, on a flat broad rock.”

The recent photograph after a no less perilous climb has been chosen to illustrate the perched position of the

stone.

Nikon D810; 28 -300; 28 mm; 1/320 at f11 ISO 250

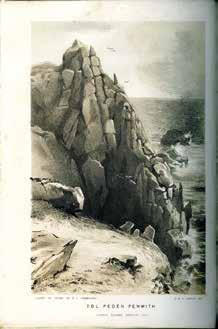

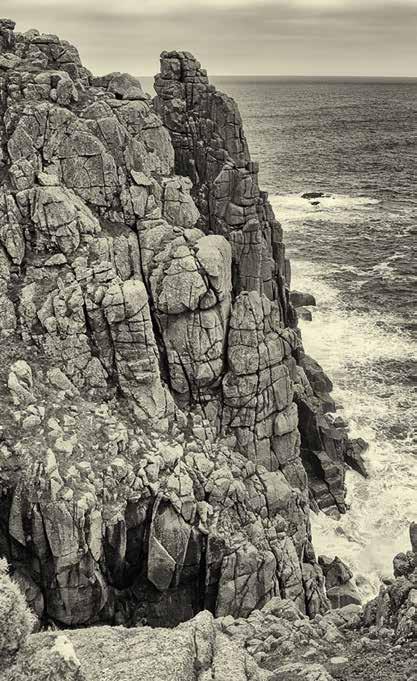

Tol-Peden-Penwith

Mid-way between the Logan Rock and Land’s End lies “the desolate pile of rocks and caverns which form the towering promontory, called Tol-PedenPenwith, or, The Holed Headland on the Left.” The latter may refer to “a black, yawning hole that slanted nearly straight downwards, like a tunnel, to unknown and unfathomable depths below” which is located a short walk to the west of the headland. This is the likely spot where, in Collins’s 1852 novel Basil, the villain of the story falls to his death. The photograph gives a reasonable match to the lithograph but the artist has had the luxury of moving the horizon to his preferred position.

Nikon D810; 28-300; 28 mm; 1/320 at f8 ISO 800

Nikon D810; 28-300; 28 mm; 1/320 at f8 ISO 800

Land’s End

Furthest west, of course, is Land’s End. “Granite, and granite alone, that you see ….. presenting an appearance of adamantine solidity and strength….. The solitude on these heights is unbroken - no houses are to be seen - often, no pathway is to be found.” Unlike Collins’s time, Land’s End is a commercial horror of modern attractions, a victim of its own success. Only go if you’ve never been: If you’ve been before, don’t go back! In any event, here we have more artistic licence but, in this case, it is the photographer who has cheated by flipping the image horizontally to match the original as closely as possible.

Nikon D810; 18-35; 18 mm; 1/125 at f16 ISO 400

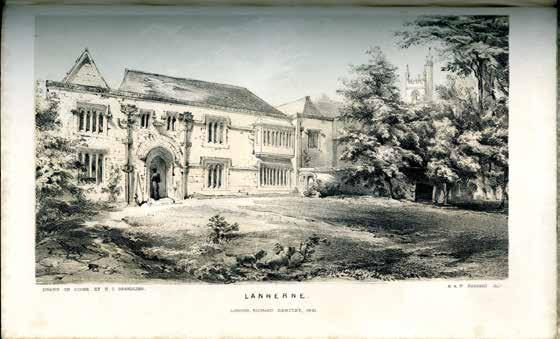

Lanhearne

About 50 miles north-east of Land’s End lies the village of St Mawgan, close to Newquay. Here is found the Carmelite convent of Lanhearne, given to the nuns as a refuge from overseas persecution. “The strictness of their order is preserved with a severity of discipline which is probably without parallel anywhere else in Europe.” Now, as then, the nuns never leave the convent and are never seen. Once again, the artist has the advantage over the photographer, for even at 18 mm it is only just possible to include the adjacent church as well as the convent.

Nikon D810; 18-35; 18 mm; 1/125 at f16 ISO 400

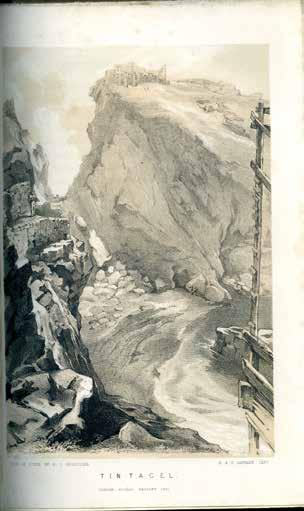

Tintagel

The travellers returned along the north coast, where most of the places visited, such as Botallack mine (now reincarnated as Poldark) and St Nectan’s Glen, are described but not illustrated in Rambles. The exception is the last important point of interest represented by the final illustration - “Tintagel Castle, an ancient ruin magnificently situated on a precipice overhanging the sea.” Once again Brandling uses artistic licence and exaggerates the ruins to look like significant remains of the legendary castle. Even in 1850 the ruins “only consist of a few straggling walls, loosely piled up.” Since the photograph was taken in April 2019, this relatively unspoiled view of Tintagel is no longer possible because of the new high-level bridge between the two headlands.