26 minute read

Understanding and Using Financial Statements in Valuations and Planning

By Stephen J. Bigge, Timothy K. Bronza, Abigail R. Earthman, and Bruce A. Tannahill

Stephen J. Bigge, CPA/PFS, is a partner at Keebler & Associates, LLP. Timothy K. Bronza is the president of Business Valuation Analysts, LLC. Abigail R. Earthman is a partner at Perkins Coie LLP. Bruce A. Tannahill is a director of advanced sales with a large mutual life insurance company.

Financial statements and valuation reports tell stories— stories about the business that is the subject of the financial statements. Unlike a novel, whose plot reveals itself as you read, many of the stories in financial statements are hidden and you must dig below the surface to find them before you can use them. It’s easier for people to remember and understand numbers as part of stories, rather than just the numbers themselves.

This article will discuss the key financial statements for a business and ways to use them to uncover the full stories that they tell, as well as describe how they are used in valuation reports. An individual’s financial statements are very similar and are built on parallel accounting principles.

The stories provide information about the company’s financial health: How is it doing? Is it likely to continue in business or is it at risk of failing? The stories help you understand the entity’s operations and its primary market: How does it produce income? Who are its customers? What kind of expenses does it incur? You can often approximate the financial fitness of one entity by comparing its financial statements to the statements of other entities.

Together, financial statements and a valuation report can tell the story of a business. For the story to be effective, the financial statements and valuation report must be consistent. Otherwise, the story will fall apart.

Lawyers should understand the basics of financial statements so that they can ask questions of the certified public accountant (CPA) and appraiser about what stories were told through the financial statements. The financial statements can help you understand a company’s financial health: Is it a viable going concern? Can it continue without major changes?

By delving into the financial statement details, you get an overview of how the company operates: where it gets its money, where it derives its profits, and how it spends its money. Combining financial data with information obtained from the company’s management should provide a good overall picture of the company.

Key Financial Statements

There are three key financial statements, also referred to as the accounting trinity:

• Balance sheet,

• Income statement, and

• Statement of cash flows. We’ll look at the purpose of each financial statement and include an example of each.

Balance Sheet

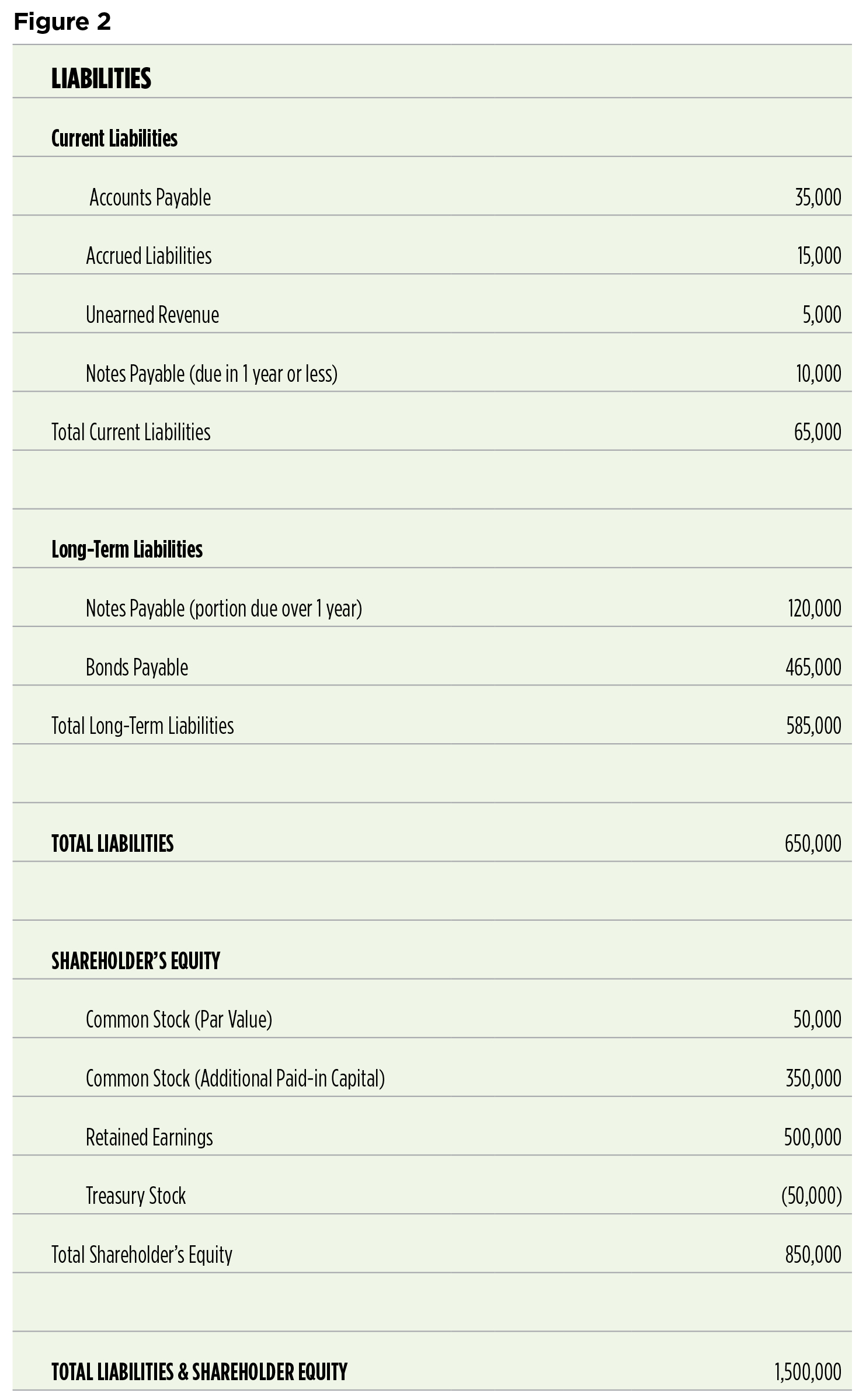

A balance sheet presents an entity’s assets, liabilities, and owner’s equity at a specific point in time, often the end of a month, quarter, or year. See Figures 1 and 2. The relationship among the assets, liabilities, and owner’s equity may be expressed as an equation: Assets = Liabilities + Owner’s Equity. Balance sheets are often displayed in a table with the assets on the left side and liabilities and owner’s equity combined on the right side.

Types of Assets. There are two general types of assets: current assets and longterm assets. Current assets are expected to be turned into cash (or cash equivalents) or be consumed in one year or less. These assets include cash, receivables, inventory, and prepaid expenses (expected to be used within one year).

Long-term assets are expected to be retained by the business for more than one year. Examples are land, buildings and improvements, machinery and equipment, investments, and notes not expected to be received within one year.

Marketable securities can be either current assets or long-term assets, depending on the nature of how they’re being held and the intentions for those marketable securities.

Intangible assets have value to the entity but do not have physical form. Examples include patents, copyrights, trademarks, and goodwill. Goodwill may be described as a basket of intangible assets that cannot be sold or exchanged in the marketplace and can be identified only with the business as a whole. Goodwill is recorded only when an entire business is purchased because goodwill represents “going-concern” value and cannot be separated from the business as a whole.

Types of Liabilities. Current liabilities are debts expected to be paid within one year or less. Common current liabilities include accounts payable, accrued payroll expenses, accrued tax liabilities, and unearned revenues. A common form of unearned revenues is rent that has been received for periods extending beyond the balance sheet date. For example, if a tenant paid rent for January on December 30, the payment would appear as unearned revenues on a December 31 balance sheet because the tenant’s occupancy of the property in January has not yet occurred.

Long-term liabilities are those not expected to be paid within one year, such as notes payable, mortgages payable, and bonds payable. Amounts due on a note, mortgage, or bond within one year should be reported as current liabilities.

Types of Owner’s Equity. The financial statement presentation for owner’s equity differs between corporations and other types of entities (sole proprietorships, partnerships, and LLCs).

Noncorporations (sole proprietorships, partnerships, LLCs) generally break down their owner’s equity into the capital account and the draw account.

Noncorporations (sole proprietorships, partnerships, LLCs) generally break down their owner’s equity into the capital account and the draw account.

• The capital account reflects contributions by the owners to the entity and the accumulated net earnings and losses. A company may have two different types of equity:

o Preferred equity provides a liquidation preference, guaranteed rate of return based on the amount of capital contributed, or both. It may or may not have voting rights.

o Common equity generally controls the entity through the voting rights.

• The draw account reflects the cumulative distributions made to the owners.

For corporations (C corporations and S corporations), owner’s equity is broken down into contributed capital, retained earnings, and treasury stock. Unlike noncorporate entities, separate accounts are maintained for contributed capital and retained earnings.

• Contributed capital reflects contributions by the shareholders to the entity.

o Par value is the value set in the corporate charter as the minimum price at the initial offering.

o Additional paid-in capital (“capital surplus”) is the excess of the actual price paid over the par value when the shares were issued.

• Retained earnings are the corporation’s cumulative earnings less dividends paid.

• Treasury stock is the value of the corporation’s own stock it has repurchased.

Key Balance Sheet Concepts. When reviewing a balance sheet, there are several key concepts to keep in mind:

• Balance sheets are usually reported at cost.

• Fixed assets are reported at their depreciated value (cost minus accumulated depreciation).

• Intangibles are reported at their net amortized value (cost minus accumulated amortization).

• Certain assets must be reported at their “net realizable value” (i.e., how much the entity could get for the asset if the entity were to liquidate):

o Accounts receivable.

o Inventory.

• Under the “conservatism principle,” assets are slow to be recorded and quick to be written down, while liabilities are quick to be recorded and slow to be written off.

Assets such as fixed assets and intangibles that are shown at a net value may be shown either at their cost value less the accumulated depreciation or amortization or simply at their net value.

Income Statement

An income statement (sometimes called a “profit-and-loss statement” or “P&L statement”) shows the entity’s economic performance over a period of time, such as from January 1, 2023, to December 31, 2023. This differs from a balance sheet, which is a snapshot of the entity’s financial position on a specific date. An income statement is usually a good indicator of where the entity is headed financially.

An income statement reports the entity’s revenues, cost of revenues or cost of goods sold (COGS), expenses, and other items. Two equations show the relationship among the income statement components:

Revenues – Cost of Revenues = Gross Profit

Gross Profit – Expenses ± Other Items = Net Income (Net Profit)

Revenues represent gross income from the entity’s continuing operations. Revenues are generally recognized when earned, not when cash is received. This is known as the accrual basis of accounting. Most entities use the accrual basis of accounting, but most individuals use the cash basis of accounting. For tax purposes, individuals must use the cash basis.

Cost of revenues or COGS represents expenses directly related to producing the goods, services, or both that are sold. These expenses often include:

• Direct materials.

• Direct labor.

• Allocable indirect expenses (overhead):

o Wages and salaries paid to material handlers and maintenance people.

o Rent paid on equipment leased to produce products.

o Depreciation on assets used in production.

o Utilities paid that are related to production.

Expenses not directly connected to producing goods or services are many times shown separately and often include:

• Selling expenses, including salaries and wages of sales and marketing staff or research and development staff.

• Marketing expenses.

• Research and development costs (may also be included in cost of revenues or as a separate type of expense).

• Administrative expenses (executive management salary and legal and professional costs).

• Head office building.

Other income and expense items not directly related to the entity’s primary business are shown separately. These frequently include interest income, interest expense, gains and losses, and income taxes. Figure 3 presents an example of an income statement.

Key Income Statement Concepts. Key concepts to keep in mind when reviewing an income statement are:

• Income and expenses are generally reported in the period incurred, not when paid (the accrual method of accounting).

• The “conservatism principle” requires adjusting revenues downward if the company expects that the full amount will not be received.

• Expenses are usually quick to be recognized if the company expects that they will be incurred.

• Cost of revenues or COGS includes only expenses directly related to the production of income.

• “Other items” (e.g., gains and losses from sales of assets, interest income, interest expense) are reported after net operating income because they are not part of the entity’s ongoing operations.

Statement of Cash Flows

A statement of cash flows (sometimes called a “cash flow statement”) measures an entity’s cash inflows and outflows over a period of time (e.g., January 1, 2023, to December 31, 2023). As with the income statement, it’s most often measured annually and quarterly.

The statement of cash flows reconciles the beginning and ending balances of the cash account and is normally used to see how the entity is managing its cash receipts and disbursements. Although it measures the entity’s activity over a period of time like an income statement, the statement measures cash rather than income and so can produce very different results. Cash flow may not equate to profitability and profitability may not result in cash flow.

For estate planning purposes, the statement of cash flows may be useful to analyze if there is sufficient cash flow and liquidity to settle obligations created as part of the estate plan.

The statement of cash flows shows the results of cash flows from three different sources:

• Operating activities,

• Investing activities, and

• Financing activities.

Cash flow from operating activities starts with the net income shown on the income statement and adjusts it for certain items. The following items are added back:

• Depreciation and amortization.

• Losses from the sale of assets.

• Decreases in most current assets (e.g., inventory and receivables).

• Increases in most current liabilities.

The following items are subtracted:

• Gains from the sale of assets.

• Increases in most current assets (e.g., inventory and receivables).

• Decreases in most current liabilities.

Figure 4 shows an example of a statement of cash flows from operating activities.

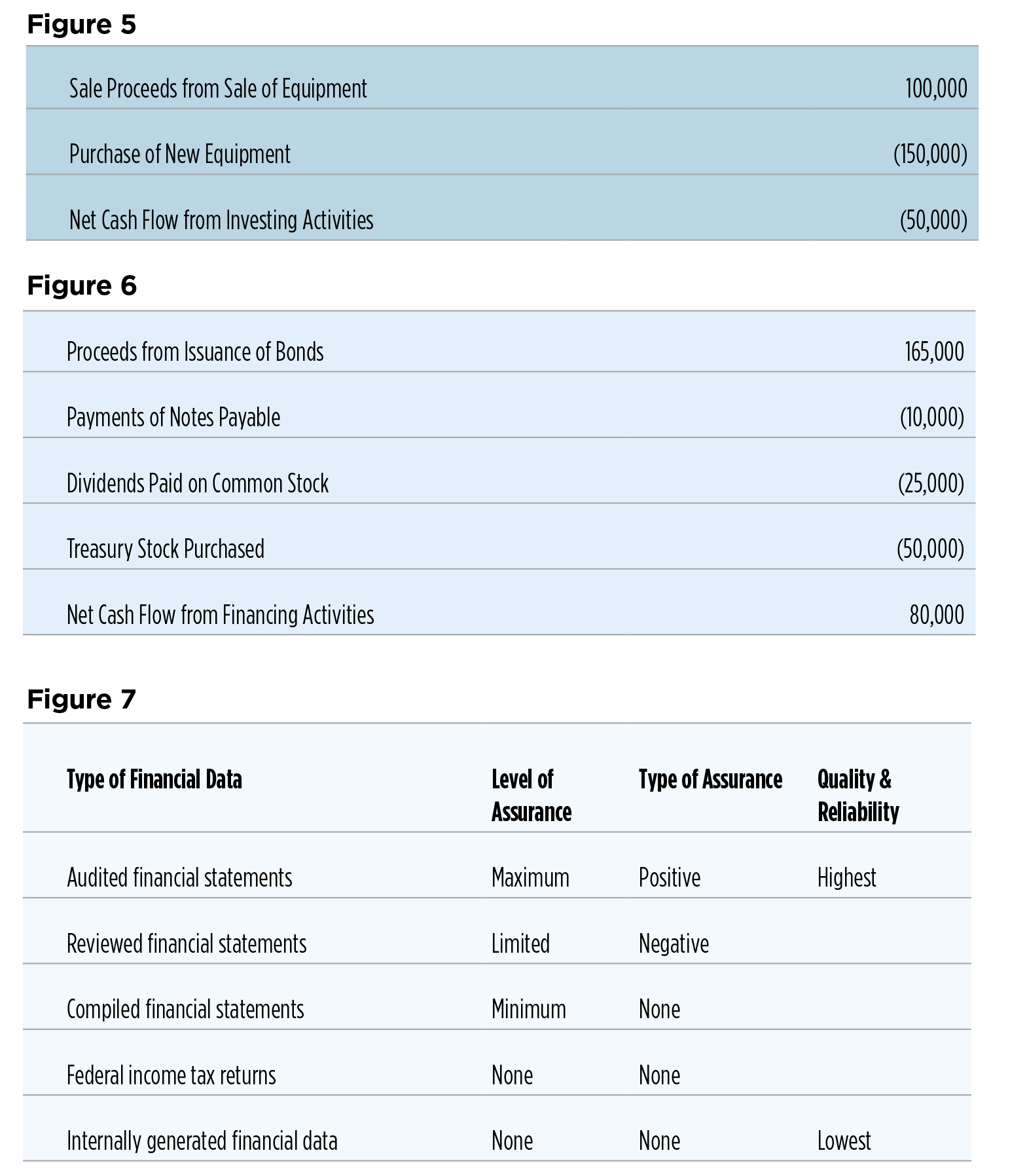

Cash flow from investing activities measures the cash inflows and outflows from sales and purchases of long-term investments, such as capital assets. Long-term investment purchases decrease cash flows, and sales of long-term investments increase cash flows. Figure 5 presents the portion of the statement of cash flows reflecting investing activities.

Cash flow from financing activities measures inflows from issuing or acquiring new debt, new stock, or both and outflows from paying dividends and long-term debt. Items that increase cash flow:

• Issuing or acquiring long-term debt.

• Issuing more stock. Items decreasing cash flow:

• Repaying long-term debt.

• Paying dividends.

• Purchasing treasury stock.

Figure 6 presents an example of the portion of the statement of cash flows from financing activities.

Hierarchy of Financial Information

Figure 7 presents the hierarchy of financial information by source. It provides users of the financial information guidance on the assurance, quality, and reliability of the statements.

“Level of assurance” refers to the level of confidence provided by a certified public accountant, based on the extent of the CPA’s testing and examination of the financial information.

“Type of assurance” identifies that the confidence in the information presented is positive or negative or no assurance is being provided. Positive assurance involves a CPA providing an opinion that indicates the financial statements fairly represent the financial results and financial position in all material respects. Negative assurance involves a CPA indicating that nothing has come to the attention of the CPA during the scope of services that the financial statements do not fairly represent the financial results and financial position of the entity. No assurance indicates that a CPA’s scope of services is such that no assurance is provided or a CPA is not associated with the financial information of the company.

The ultimate responsibility for the accuracy of the financial statements is with the company’s management, not the outside CPA. Many small companies don’t have the accounting infrastructure or the need to prepare audited or reviewed financial statements.

See the sidebar toward the end of this article for a description of the different types of audited, reviewed, and compiled financial statements that may be prepared by a CPA.

Using Financial Statements in Valuations

Financial statements tell a company’s story, albeit in numerical form. A well-prepared valuation report connects the story of the company to the details of the numbers. A valuation driven solely by a story falls apart without solid financial (quantitative) support. Similarly, a valuation driven solely by the numbers falls apart without solid qualitative support.

It is important for the appraiser to keep the intended audiences in mind. Usually, the audiences include the estate planning attorney, a tax controversy lawyer, an IRS estate and gift tax examining attorney, an appellate conferee, and a Tax Court judge. This audience tends to be more verbally oriented than quantitatively oriented, making the story more important.

When material financial information isn’t explained, or isn’t explained well, the attorney is likely to raise inquiries and ask probing questions to vet the information.

Analyzing a company’s financial statements is central to identifying strengths and weaknesses (assessing risk). Although past results don’t predict future performance, analyzing past results provides a proxy for the future and a basis for the appraiser’s judgments about future results (assessing growth prospects). This is especially the case when the company doesn’t have the ability to provide forecasts and budgets. Financial statement analysis most often involves a comparison of the company against other companies in their industry.

An appraiser’s financial statement analysis involves several steps:

1. Prepare comparative historical financial statements (income statement and balance sheet), typically for five years.

2. Apply normalizing adjustments, controlling interest adjustments, or both.

3. Prepare a trend analysis for both revenue and earnings.

4. Prepare common size analysis to historical adjusted financial statements.

5. Prepare an analysis of financial ratios, inclusive of liquidity, activity, profitability, and coverage or leverage ratios.

6. Assess the risk and growth prospects of the subject company and its industry peers.

7. Incorporate the conclusions formed from financial statement analysis consistently throughout the valuation methodology.

Valuation Guidance on Financial Statement Analysis

The importance of financial statement analysis in appraisals has long been emphasized by the IRS and other official entities.

The IRS’s detailed valuation guidance came in Revenue Ruling 59-60 (1959-1 C.B. 237), which set out valuation guidelines. The agency recommends the appraiser obtain two or more years of balance sheets, a balance sheet as of the month end preceding the appraisal date, and detailed income statements for the preceding five years. The ruling notes the variety of information shown on balance sheets and income statements and emphasizes the importance of comparing the financial statements over a period of years. When the IRS receives anppraisal, the first thing it looks for is how the appraisal conforms to Rev. Rul. 59-60. Any deviation from that ruling or standard practice may be flagged for further scrutiny.

The Valuation Training for Appeals Officers Coursebook (Training 6126-002, Rev. 05-97) notes that analyzing financial statements tell a great deal about a business’s strengths and weaknesses. It recommends that the analysis include a comparison of certain key ratios with either a standard for the industry or selected comparable companies.

Internal Revenue Manual 4.48.4, Engineering Program, Business Valuations Guidelines (July 1, 2006) states that historical financial statements should be analyzed and adjusted as necessary to reflect the appropriate asset value, income, cash flows, or benefit stream, as applicable, to be consistent with the appraiser’s valuation methodologies.

The Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP) were developed following the 1980s savings and loan crisis. USPAP sets out recommended procedures and ethical standards for appraisers and is updated every two years. The Appraisal Subcommittee of the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, created by Congress in 1989, works with the Appraisal Standards Board of The Appraisal Foundation to monitor state supervision of appraisers. USPAP is not binding for federal tax valuation but is binding on the appraisers who are members of member appraisal organizations of the Appraisal Foundation. Tax Court judges often refer to these standards. For appraisers, USPAP serves a function similar to that served by generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) for accountants. Standards Rule 9-4, Approaches to Value, subsection (b)(iii), states that an appraiser must analyze the effect on value of past results, current operations, and future prospects of the business enterprise when necessary for credible results. This is the essential goal of financial statement analysis.

Financial Statement Adjustments

Appraisers adjust financial statements to present the financial statements to reflect normal operating conditions or to value business interests that possess control of an entity. The adjustments may affect the income statement, balance sheet, or both, and are classified as either (1) normalizing or (2) controlling adjustments.

Normalizing Adjustments. Normalizing adjustments attempt to account for items shown in the historical financial statements by eliminating unusual and nonrecurring items that distort historical operating results or financial position. For example, income from the forgiveness of Paycheck Protection Plan loans is expected (and hoped) to be a one-time event. Other examples of common normalizing adjustments include:

• Segregating nonoperating assets or liabilities from those related to the business’s operations.

• Accounting for excess operating assets.

• Using the applicable accounting principles.

• Reflecting taxes imposed on the business’s operations.

Controlling Adjustments. Appraisers apply controlling adjustments when valuing a majority (more than 50% of the voting equity) interest in an entity. These adjustments reflect a majority or controlling owner’s ability to control or influence the amount paid in dealings with related parties or for expenses that are personal and unrelated to the business. Controlling adjustments are not appropriate for the valuation of a minority interest. Common controlling adjustments include:

• Adjusting owner compensation up or down to market compensation.

• Non-arm’s-length transactions.

• Discretionary expenses.

• Rental expenses paid to related parties.

• Other related-party or non-arm’slength transactions.

If material omissions or deficiencies are present in the financial statements (e.g., not having the statement of cash flows), it’s up to the appraiser’s discretion to determine the effect of the deficiencies and determine whether a reliable opinion of value can be provided. If the appraiser concludes that such an opinion cannot be provided, the appraiser has a professional responsibility to withdraw from the engagement. The appraiser should clearly and prominently disclose any material omissions or deficiencies related to the financial data that are relied upon for the opinion of value.

Financial Statement Analysis

Once normalizing and controlling adjustments have been made, the next step in discovering the story of the financial information of the business is to analyze the financial statements. The analysis varies with the business, but commonly includes trend analysis, common size analysis, and financial ratio analysis.

Trend Analysis. Identifying trends can be helpful to ascertain how a business is performing. Trend analysis frequently involves reviewing historical results (e.g., gross revenues, gross profits, net profits, etc.) over a period of time. After identifying trends, the appraiser can investigate the reasons behind the trends and determine how the trends affect the business value. There should be a logical explanation for the variations in historical income statements and balance sheets in the narrative and the report.

Common Size Analysis. Common size analysis reviews comparative balance sheets and comparative income statements over time, seeking to identify trends and variations that require explanations. For the balance sheet, each balance sheet account is presented as a percentage of total assets. On the income statement, each income statement account is presented as a percentage of total revenues.

Common size analysis should also involve comparing prior budgets (if available) against historical financial information to judge the reliability of the current budget. Finally, the appraiser should review the strategic plan and discuss the future outlook of the company with its management with an eye for how the prospective financial information compares with historical financial information.

This appraisal should include a qualitative analysis of variations, not just the financial information itself.

Financial Ratio Analysis. Financial ratio analysis compares the financial ratios of the subject company against financial ratios of the company’s industry peer group. The industry metrics are obtained either from public guideline companies or from reliable sources that compile data on private companies. Optimally, financial ratio analysis will consider liquidity, activity, profitability, and coverage or leverage ratios.

Liquidity Ratios. Liquidity ratios measure a company’s ability to meet its current obligations. Generally, the higher the ratio, the better the company’s financial health. Common liquidity ratios are:

• Current ratio Current assets divided by current liabilities. This ratio shows the company’s ability to meet its current obligations.

• Quick (“acid test”) ratio. Cash equivalents plus accounts receivable divided by current liabilities. The quick ratio uses only those current assets that can be accessed quickly, excluding current assets such as inventory and prepaid expenses. Because it uses only the most liquid assets, the quick ratio is a more conservative measure than the current ratio.

Activity Ratios. Activity ratios measure how efficiently a company utilizes its assets. Common activity ratios include:

• Accounts receivable turnover ratio. Revenues divided by accounts receivable. This shows how long the company takes to collect its accounts receivable. The shorter the period, the better.

• Inventory turnover ratio. Cost of goods sold divided by inventory. A low ratio may indicate weak sales or excess inventory, but a high ratio can indicate strong sales or low inventory.

• Working capital turnover ratio. Revenue divided by net working capital (current assets minus current liabilities). The higher the ratio, the more efficient the company is at using its working capital to generate revenue.

• Total asset turnover ratio. Revenues divided by total assets. The higher the ratio, the more effective the company is at utilizing its assets.

Profitability Ratios. Profitability ratios measure a company’s operating performance. Common profitability ratios include:

• Operating margin. Operating income divided by revenue. The operating margin identifies the percentage of revenue remaining after deducting operating expenses. The higher the operating margin, the more funds are available to pay nonoperating expenses.

• Net profit margin. Net income divided by revenue. The net profit margin shows the percentage of revenue left after paying both operating and nonoperating expenses.

• EBITDA margin. EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) divided by revenue. EBITDA approximates operating cash flow by subtracting the noncash expenses of depreciation and amortization from earnings before interest and taxes. The EBITDA margin compares EBITDA to revenue. The result identifies operating profitability and cash flow and makes it easier to compare the profitability of companies with different financial structures.

• Return on assets, pre-tax. Earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) divided by total assets. This ratio shows how efficiently the company generates profits from its assets.

• Return on equity pre-tax. EBIT divided by owner’s equity. This ratio focuses on how efficiently the company uses its equity, rather than its assets. The use of a measure of return on equity removes the effect of the company’s use of debt to finance its operations.

Coverage and Leverage Ratios. Coverage and leverage ratios measure a company’s risk related to its reliance on debt to sustain its operations. Common coverage and leverage ratios include:

• Interest coverage. EBIT divided by interest expense. This ratio shows the company’s ability to pay interest due on its debt from its operating earnings.

• Debt to total assets. Interest-bearing debt divided by total assets. This ratio measures how much of a company’s assets are financed by interest-bearing debt and can provide insight into the company’s financial stability. The higher the ratio, the greater the company’s financial risk.

• Total liabilities to total assets. Total liabilities divided by total assets. This ratio uses all liabilities, including accounts payable, accrued salary, and retirement plan obligations, which are excluded from the debt to total assets ratio. The higher the ratio, the greater the company’s financial risk.

Using the Ratio Analysis. Frequently, companies outperform their industry metrics in some areas, underperform in others, and are comparable in still others. The appraiser should analyze the company in its totality, address the company’s strengths and weaknesses financially, and then conclude how well it compares against the industry metrics. One of three conclusions should be reached: (1) the company is superior financially to the industry peer group, (2) the company is comparable financially to the industry peer group, or (3) the company is inferior to the industry peer group. This sets the stage for a comparison of the capital market evidence used to support the opinion of value.

Conclusions

A company’s financial statements tell a story of the company’s financial performance and financial position. The valuation narrative should reflect the appraiser’s financial statement analysis and assessment of the company’s risk and growth prospects. Those should be extended to other aspects of the valuation analysis and be consistent throughout that analysis.

A good valuation will provide a seamless explanation of past financial results that leads to well-substantiated assessments about the company’s future performance, providing the foundation for the valuation.

Valuation revolves around three fundamentals: (i) level of earnings—trying to ascertain that through financial statement analysis, (ii) risk associated with the earnings, and (iii) growth prospects. A good framework to use when looking at valuations involves going back to those three fundamentals that really drive value. The conclusions related to these fundamentals should be woven into the valuation narrative.

Learning about financial statements and valuation is an art—it’s really learning a whole new vocabulary. The more fluently lawyers can use that vocabulary with the appraiser and CPA, the more effective those conversations will be. Without that general background, an attorney can’t have the initial conversation to tell the appraiser, “I like what you’re doing here, but I think you missed adequate consideration of this concept that can affect the overall valuation.” Attorneys who are well positioned to ask probing questions are going to elicit thoughtful responses from appraisers. Appraisers must be independent and objective and make judgment calls, but discussions with knowledgeable attorneys will make an appraiser’s work product much more effective and meaningful, well positioned to realize accepted-as-filed outcomes or, in the event of an examination, quick and favorable resolution.

TYPES OF CPA REPORTS ON FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

CPAs issue three different types of reports on financial statements. The CPA’s level of assurance varies depending on the type of report they have been engaged to provide.

Audited financial statements are financial statements prepared by the entity and examined by a CPA. The goal of auditing financial statements is to determine whether the statements fairly present the entity’s results, financial position, and cash flows, in accordance with GAAP. The auditor will:

• Test and evaluate the company’s internal controls by reviewing the policies and procedures established to provide reasonable assurance of the veracity of the financial information to determine their effectiveness and the reliability of the financial statements,

• Evaluate the company’s assumptions reflected in the financial statements, and

• Test the amounts and information in the financial statements to the company’s records, and request confirmation from third parties for financial information of a material amount.

The auditor does not examine all transactions, instead relying on a combination of adequate planning, evaluation of internal control testing , and judgment to determine the amount of evidence required before forming an opinion on the financial statements.

After completing an examination of the company’s financial records and statements, the auditor will issue an opinion on the financial statements. There are four types of opinions:

• Unqualified (clean) opinion. States that the financial statements fairly present the company’s financial condition, position, and operations in accordance with GAAP.

• Qualified opinion. Issued if the financial statements do not follow all of the elements of GAAP that apply, the auditor was not able to verify certain material information, or the audit was limited. The opinion will state the reason for the qualified opinion.

• Adverse opinion. Issued if the auditor believes the financial statements aren’t presented fairly in accordance with GAAP. The opinion will normally outline the reasons for the adverse opinion.

• Disclaimer. The auditor does not express any opinion on the financial statements. Disclaimer opinions may be issued if the company significantly limited the scope of the audit, the auditor has significant doubt that the company can continue as a going concern, or there exists an absence of reliable financial information.

Reviewed financial statements are financial statements prepared by the company, followed by a CPA performing analytical procedures and making inquiries of the company’s management and others to determine whether any material modifications to the financial statements are necessary to bring them into compliance with GAAP.

As with an audit, after completing a review of the financial statements, the CPA will issue a report stating the CPA’s conclusion about the reviewed financial statements. Importantly, in contrast to an audit (where the CPA provides positive assurance that the financial statements are fairly stated in conformity with GAAP), the review provides negative assurance, i.e., nothing has come to the CPA’s attention that the financial statements are not in conformance with GAAP. The conclusion may be one of three types:

• Unmodified. The CPA is not aware of any material modifications required for the financial statements to be in accordance with GAAP.

• Modified. The CPA determines that the financial statements are materially misstated and explains this conclusion in one of two ways.

o Qualified conclusion. The effects of the required modifications are material but not pervasive in the financial statements.

o Adverse conclusion. The effects of the required modifications are both material and pervasive to the financial statements.

Compiled financial statements simply present the financial statements based on information provided by the company, without the CPA performing any analytical procedures or making any inquiries about the financial statements. The CPA’s objective is to assist management in presenting financial information in the form of financial statements. The CPA’s report accompanying the compiled statements doesn’t express any opinion on the statements and in thus does not provide any assurance related to the financial statements.