Introduction

A core part of Jewish values is the belief that we are all connected, and it is our responsibility to look out for one another and the world around us. The sense of connection and engagement, shared values, and identity is a core element of our Jewish community and the focus of this report.

Recent years have brought about change to the fabric of American society as a whole and have affected the Jewish community as an integral part of that society. This report is based on a study conducted in 2019 and 2021 by the Ruderman Family Foundation and the Mellman Group. The report explores the trends and changes in identity, perception, and engagement of American Jews, spotlighting long- and short-term events taking place in the Jewish community and across the United States.

Our report reviews multiple facets of the current experience of American Jews and suggests, among others, that a large portion of the Jewish population currently is not engaged in Jewish organizations, nor has strong aspirations to be. Those who are engaged express the need for organizations to become more open, inclusive, and adaptive to the needs and ambitions of the people they are working with. While Israel is an important part of Jewish identity, concerns about an emphasis on Israel and Israeli politics can be an obstacle to involvement. Community organizations and institutions will need to look at ways to get beyond these tensions and show their work to adapt and keep in touch in order to deal with the many challenges ahead.

Jay RudermanPresident and Chair of the Board

Ruderman Family Foundation

Executive Summary

This report presents the findings of two surveys of American Jews conducted in 2019 and 2021. These surveys examined overall attitudes related to Jewish identity, community organizations and institutions, and Israel. They also explored current issues including the changing political landscape in both countries, the rise in antisemitism incidents in the United States, and the COVID-19 pandemic which spread in the United States shortly after the first survey was conducted.

The 2021 survey adopted an approach different from previous studies of the Jewish community. It was conducted only among those who had participated in the 2019 survey. This kind of recontact research allowed us to look under the surface at individual-level change and explore trends across the broader population. This is the first time, to our knowledge, that this recontact methodology has been used in survey research on American Jews.

KEY FINDINGS

Most American Jews share a sense of identity. Despite the personal sense of Jewish identity, fewer American Jews are engaged with Jewish communal institutions.

American Jews feel that antisemitism is rising and see it as a big concern. Yet, it does not affect their motivation to become involved with the Jewish community.

Jewish community institutions are perceived overall in a positive light, but not everyone feels well represented.

The unengaged do not have a negative perception about the institutions, but are much more likely than the engaged to see them as not representing them, and being too focused on Israel, big donors and partisan politics.

A majority believes that community institutions should be doing more to be inclusive and stay in touch.

For many, maintaining their Jewish identity is not related to Jewish communal institutions.

Surprisingly, many of the smaller, potentially marginalized groups within the Jewish community are less likely to see institutions as unwelcoming.

The top motivations for the involvement of Jews are sustaining and maintaining the community for themselves and future generations, along with the connection to Jewish history.

Donations, holiday celebrations, and reading Jewish publications are among the most common forms of involvement.

Some are disengaged by choice – with lack of time and competing priorities two of the top reasons for not being involved.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic does not appear to have left a deep imprint on donors or their views of community organizations, it may be the reason for the slight decrease in engagement with community organizations.

Most have some attachment to Israel, but it is stronger among those who are more engaged.

Most are familiar with the Boycott Divestment Sanctions (B.D.S.) movement and are strongly opposed to it.

The majority of American Jews are pro-Israel but critical of at least some Israeli policies.

The majority of American Jews see the two US political parties headed in opposite directions on Israel, with the Republican Party (GOP) becoming more supportive, and the Democratic party less so.

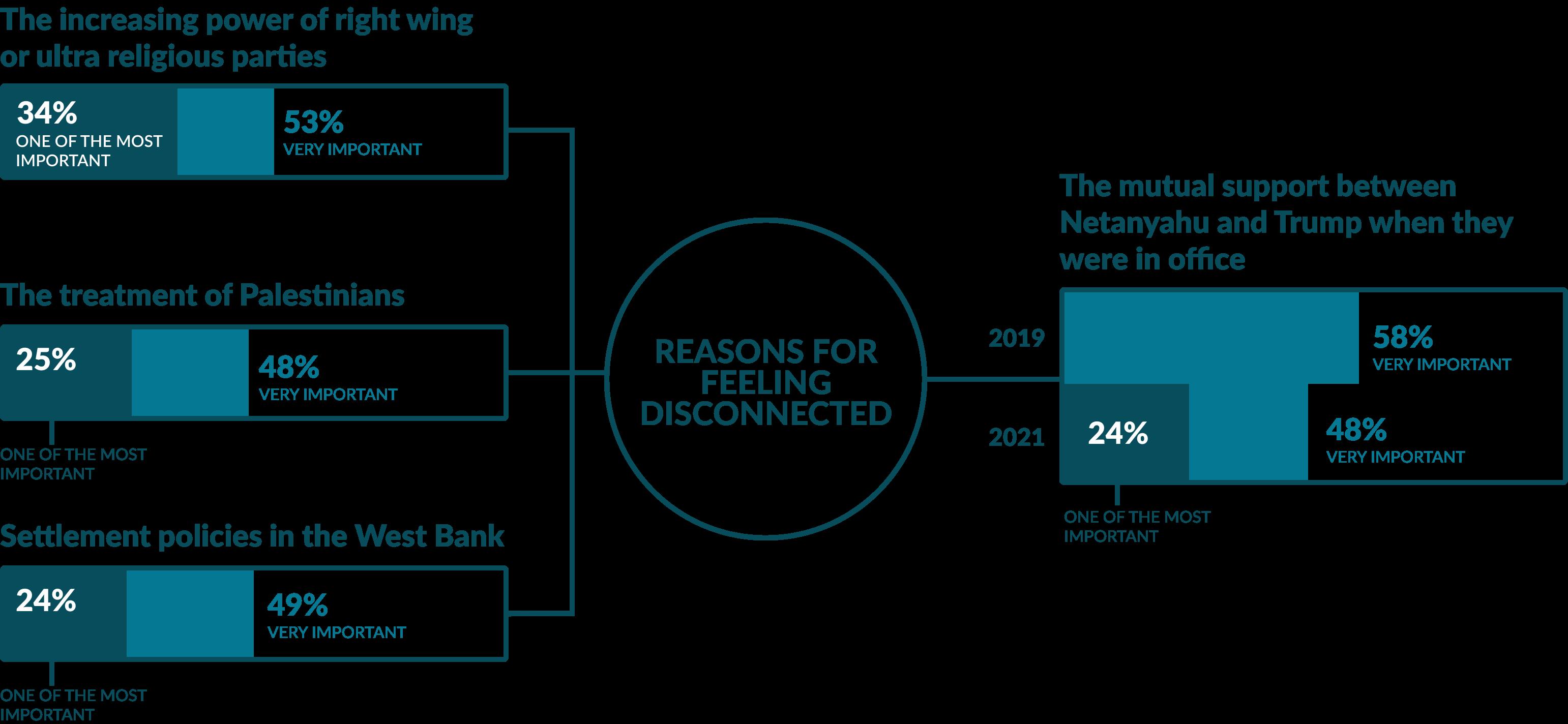

Among the main reasons for feeling less connected to Israel are the political tensions over religious parties, settlement policies, and specifically, lingering feelings about the TrumpNetanyahu alliance that persisted even after the 2020 elections.

Methodology

This report is based on two online surveys of American Jews conducted in 2019 and 2021. The surveys were designed by The Mellman Group in consultation with the Ruderman Family Foundation. The first survey was conducted among 2,500 American Jewish adults, during December 5-19, 2019. The margin of error overall is +/- 1.96%, higher for subgroups. The second survey was conducted during October 11-November 1, 2021, among 1,000 of those who participated in the 2019 survey. The margin of error is +/- 3.1% overall, higher for subgroups.

Both surveys used probability-based panels which are open to all households, and not restricted to opt-in members or other approaches which can bias or limit participation. The sample was then matched to public demographic data on Jews in the United States (U.S.), including the Pew Research Center’s Religious Life survey of American Jews. The matched cases were weighted to the sampling frame using propensity scores on demographics including age, gender, race/ethnicity, years of education, and voter registration status. In contrast to the Pew study of Jewish Americans in 2020, participants in this survey had to identify themselves as Jewish. Pew’s study included, for example, those who had a Jewish parent but did not consider themselves Jewish.

The sample size for the 2019 survey was large enough to examine data within subgroups. The survey included representation of smaller subgroups within the Jewish community, such as nonwhite and Jews with disabilities. Yet, caution should be exercised in examining extremely small sample sizes because margins of error increase as subsample size decreases. The 2021 recontact survey was conducted only among those who participated in the earlier 2019 research. The recontact cases were also matched to the same sampling frame.

The recontact methodology using the two surveys allows us to compare trends in the attitudes of American Jews and provides a comparison with changes at the individual level. Even when overall trends look fairly stable, there is usually some movement underneath the surface which can be instructive. To our knowledge, this is the first time that this recontact methodology has been used in survey research of American Jews.

A note on timing. Little did we know when we conducted the first survey that within months the entire world would be plunged into the new reality of a global pandemic. COVID-19 posed a significant challenge for many communal and social service agencies, and Jewish communal institutions were no exception. As is often the case with the Jewish community, the institutions rose to the occasion and in some ways even thrived during the crisis. At the same time, the immediacy of the crisis may have overshadowed or temporarily pushed aside other challenges

and concerns.

Another significant change that took place within the research period are the elections in both the U.S. (2020) and Israel (2021), which resulted in the incumbent leaders Donald Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu being replaced. The second survey, conducted in 2021, discusses these changes and their potential influence on the respondents’ perceptions and experiences.

Jewish Identity and the Sense of Shared Fate

The overwhelming majority of self-identified American Jews regard being Jewish as important to them. Over three quarters (80%) say being Jewish is important to them, with 44% saying it is “very important.” This is almost unchanged from two years before (2019) when 81% said it was important, and 46% said “very important.”

How important is being Jewish to you?

The vast majority value their Jewish identity and feel a connection to other U.S. Jews

Jewish identity is stronger for Orthodox (97% very important) and Conservative (59% very important) Jews. But even among those who do not identify with a particular denomination, 60% say that being Jewish is important to them and 21% that it is very important.

Jewish identity is somewhat stronger among parents with children under 18 years who live at home. Nearly all of these parents (90%) feel it is important, and 51% feel it is very important.

Jewish Identity Index paints a clearer picture

The majority of American Jews (82%) feel that what happens to Jews in this country will have “something to do with what happens in [their lives].” Over a third (38%) believe it has a lot to do with their life. There is little difference when it comes to age, with levels as high as 81%-83% across three age groups: under 40, 40-59, and 60+ years old. This sense of shared fate is higher among Orthodox and Conservative (both 93%) than Reform (80%) Jews, and remains strong even among the non-denominational (74%).

Even among the 20% who feel that being Jewish is not important to them, over a third (65%) feel this connection. One-fifth of American Jews who place less value on their Jewish identity do not feel as strongly about shared fate; only 13% of them feel it “a lot.” Still, a certain level of acknowledgment of a common bond exists.

We combined the responses to these two questions to establish a Jewish identity index based on shared fate and the importance of being Jewish. One in four (25%) is in the high range of the Jewish identity index, with the highest-level responses for both questions. Being Jewish is “very important” to them, and they believe that what happens to other Jews has “a lot” to do with their lives.

Just over a quarter (27%) are in the medium index range, with no more than one top answer of “very” or “a lot.” The identity index correlates with denomination. A 64% majority of Orthodox Jews are in the high index, decreasing to 32% for Conservative Jews, and to 11% for those who do identify with any denomination.

Contrary to what some may expect, younger Jews, under 40 years old, are more apt to be in the high index than older Jews. Among the younger, 30% are in the high Jewish identity index, compared to 20% of middle-aged Jews and 23% of seniors.

This index provides helpful context for some of the findings that follow.

Distribution of Combined Jewish Identity/Shared Fate Index (Highest Scores Had Top Respones for Both Questions)

Antisemitism in the United States

An overwhelming majority see antisemitism rising and are very concerned

Almost all American Jews (94%) see at least some Antisemitism in the United States, and a 55% majority perceive “a lot” of Antisemitism. This nearly universal view that there is antisemitism in the U.S. extends across demographics, with 94% among the non-denominational, and 90% even among those in the bottom tier of the Jewish Identity index referenced in the previous section. There are some differences in intensity, with 62% of seniors seeing “a lot” of antisemitism, compared to 52% among younger Jews. Only 44% of Orthodox Jews see a lot of antisemitism, less than other denominations, and those without a denomination (50%).

Over four in ten had experienced antisemitism. Most have not experienced antisemitism directly, but 42% say it has been directed at them, their friends, or immediate family in the last five years. This is somewhat higher among younger Jews, 52% of whom have had this direct or indirect experience with antisemitism, compared to only 36% of seniors. Although older Jews presumably have had more years within which to have experienced antisemitism, this question was only regarding the last five years.

More observant Jews are more likely to have had this first- or second-hand experience: a majority of Conservative (56%) and Orthodox (57%) Jews have had a personal experience, compared to 39% of Reform and only 31% of non-denominational Jews.

Three-quarters feel there has been an increase in antisemitism in the United States, compared with five years ago. This feeling is fairly consistent across demographics.

Most see a concerning increase in antisemitism, and two-thirds see it as a big concern for themselves

Orthodox Jews are more likely to see an increase (84%), whereas Conservative, Reform, and non-denominational Jews consistently are within the 73%-76% range. Similarly, seniors are slightly more likely to see an increase (83%), but even among those under 40 years old, over two-thirds (68%) do see an increase. Those who have experienced antisemitism over the past five years are more likely to see an increase (83%), but even among those who have no such recent experience, 69% see an increase.

The data clearly points to antisemitism being a major concern for U.S. Jews. Nearly two-thirds (65%) see it as a big concern, and one in five say it is one of their biggest concerns. The more observant, older Jews, those with a higher Jewish Identity Index, and those who have personally experienced antisemitism are more likely to see it as a bigger concern.

The concept of shared fate with other American Jews reflected in the Jewish identity index discussed earlier is useful here. Among those with the highest Jewish identity index, 84% say antisemitism is a big concern, with most of them (43%) saying it is one of their biggest concerns. Among those on the lower and bottom rungs of the index, those saying antisemitism is a big concern are only in single-digit ranges.

This connection between Jewish identity and concern about antisemitism is not necessarily a causal link. As explained later, few see antisemitism as a reason or motivation to get more involved in community organizations.

Compared to five years ago, do you think there is more antisemitism, less antisemitism or the same amount in the U.S. today?

Engagement with Jewish Communal Institutions

Valuing Jewish identity does not necessarily translate into valuing Jewish communal institutions. In the 2019 survey, 81% said that being Jewish was at least somewhat important to them, yet only 58% said that it was at least somewhat important to feel connected to community organizations. The comparison is even more striking in the case of those with the strongest feelings. Although 46% said that being Jewish was very important to them, only 21% considered it very important to be connected to institutions and organizations in the Jewish community. Even among those who felt that being Jewish was important to them, 31% felt that it was not important to feel connected to the community.

How important is it for you to personally feel a connection to institutions and organizations in the Jewish community?

Wider gaps by age and denomination emerged. Among seniors, 47% said that being Jewish was very important, yet only 17% felt the same about the connection to the organized community. Among middle-aged Jews (40-59 years old), the gap was slightly smaller between the 38% who said that being Jewish was very important to them and the 17% who said the same about being connected to the community. Among the younger Jews (under 40 years old) and parents with children at home, only 28% and 33%, respectively, felt that a connection to community organizations was very important.

The gap between feelings about the importance of being Jewish and of being connected to communal institutions is even larger for the non-denominational individuals who identify as Jewish, with 65% feeling that connection to institutions is not important. Among Reform and Reconstructionist Jews, only 16% feel that connection to community organizations is very important, with 37% and 41%, respectively, saying that it is not important.

Strength of Connection

Most feel a connection to local community organizations, but few feel very connected. In the 2019 survey, 57% felt some connection to their local community institutions, although the connection was far from strong: 32% felt very connected and 25% only somewhat connected. In the 2021 survey, a declining majority felt some connection to their local community, with 51% feeling somewhat to very connected. There is also a decrease in their intensity towards feeling connected, with those feeling most connected going down from 31% to 26%.

Eighty-two percent of those who believe the connection is important feel at least somewhat connected, and 51% feel very connected. Even among those who indicated that the connection was important to them, 18% say that they do not feel a connection.

Most of those who do not feel a connection to community institutions do not strongly value the connection in the first place. Over three-quarters of the unconnected regard feeling personally connected to the community to be unimportant. Both surveys suggest that the majority of unconnected people do not care to be connected.

Level of Engagement

Few are deeply engaged with community organizations

How connected do you personally feel with the Jewish community in the area where you live?

In 2019, 40% reported being at least somewhat engaged in community organizations or institutions, but only 11% said that they were very engaged. Sixty percent indicated that they were not very engaged, including 28% who said that they were not engaged at all. By 2021, engagement declined with only 34% saying they were actively engaged with Jewish organizations. This decline occurred across most demographics, with the Orthodox being one of the few to show an increase.

The slight decrease in engagement occurred across almost

There are several explanations for this decrease, with the main one being the impact of the pandemic on levels and types of engagement with communal institutions. It is possible that the restrictions on going to face-to-face meetings, events, or any social gatherings were the main or sole reason for this decline for those reporting being actively engaged in community organizations and institutions.

Looking at the individual level change in those who participated in both surveys shows a decline in the intensity of engagement as well. While few shifted from being engaged to not engaged, nearly a quarter shifted downward, from “very engaged” to “somewhat engaged.”

every demographic

How actively engaged are you in Jewish institutions or organizations?

The aggregate numbers mask more changes at the individual level, with one in five saying that the connection is more important than in 2019, and slightly more saying that it is less important. Most of the change is in intensity rather than in shifting between important to unimportant.

While Jews engaged in community institutions are not defined by a single demographic, the overall engagement of more observant Jews is higher. Eighty-five percent of Orthodox and 47% of Conservative Jews are engaged, followed by Reconstructionist (46%) and Reform (37%) Jews.

Age and parenthood are also key factors. Forty-three percent of younger Jews (under 40 years old) say that they are at least somewhat engaged, engagement dropping to 29% of middle-aged Jews and 29% of seniors. Engagement of parents with children at home is also higher (58%) than of those without children at home (35%). The higher level of community engagement of parents is consistent with the importance of Jewish continuity as a reason to become involved in the first place, as discussed below.

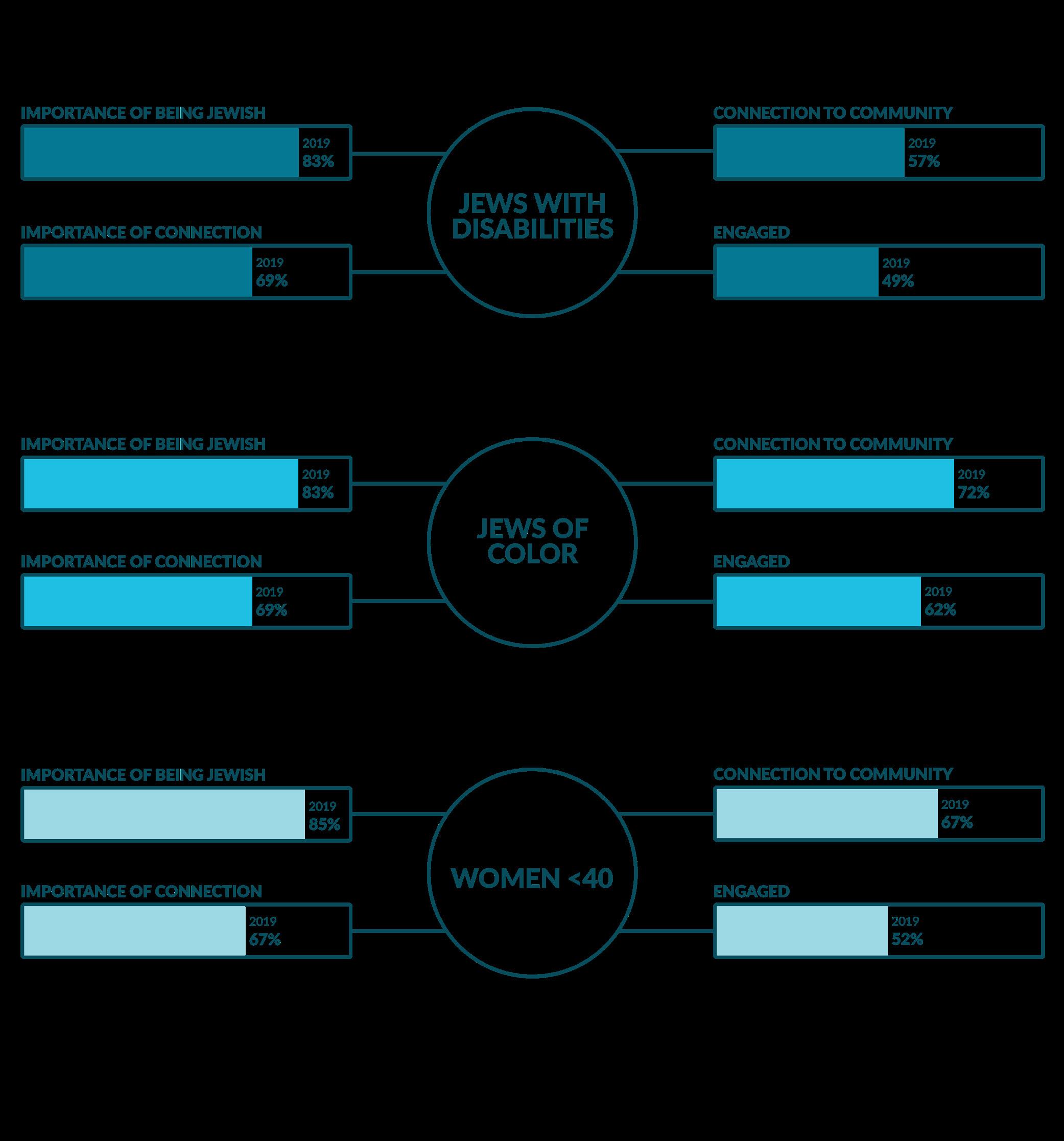

Like earlier surveys with larger sample sizes focusing on the Jewish community, this study also shows that connection and engagement are as strong or stronger when it comes to Jews with disabilities, Jews of color, and younger women. The level of engagement with community institutions is also a function of individuals’ personal connection to Judaism. Among those who

Change in engagement of respondents from 2019 survey: How actively engaged are you in Jewish institutions or organizations?

say that being Jewish is important to them, 47% are engaged, whereas among those who say it is not important, only 5% say that they are even somewhat engaged in community institutions.

Connection and engagement are as strong or stronger among the Jews with disabilities , Jews of color, and younger women.

Attitudes Toward Jewish Communal Institutions

The absence of strong engagement is by no means a sign of antipathy, but it does point to the lack of a deep connection with Jewish communal institutions. Yet, those who are familiar with the organizations see them in a generally favorable light. When exploring the positive traits of communal institutions, 56% had a favorable impression of the Jewish Federation “in your area,” with only 8% unfavorable. Feelings about their “local Jewish Community Center” were a bit better, with 66% favorable and only 6% unfavorable. But 28% did not have an impression of the local JCC, and 36% did not have an impression of the Federation.

Some of this can be attributed to a lack of interest or opinions of the unengaged Jews. Fortynine percent of these do not have an opinion about the Jewish Federation, and 39% do not have an opinion about the Jewish Community Center (JCC). It is worth noting that among the unengaged members of the community, fewer than one in ten had unfavorable opinions (7% about the Jewish Federation, 5% about the JCC).

Community institutions are generally seen in a positive light, but not everyone feels well represented

Mean Perceptions of Jewish Institutions

Jewish institutions enjoy positive perception, including helping Jews in need, Israel, those with disabilities and addressing antisemitism Almost all of those who see themselves as engaged know these institutions and have a generally favorable view of these institutions. Seventy-five percent have a favorable view of the local Jewish Federation and 81% have a favorable view of the local JCC. The table above indicates the positive and negative traits of these institutions as they are perceived by American Jews.

Overall Perception of Jewish Institutions

American Jews associate community institutions more with positive than with negative attributes. Our study asked how well a series of words and phrases describe community institutions and organizations on a scale of 1-4, where 4 means that the statement describes the organizations and institutions “very well” and 1 that it “doesn’t describe them at all.”

An average score above 3 means that it describes the institutions at least “pretty well.” The unengaged are less likely to see institutions as open, and more apt to see them as too focused on Israel, poltiics or donors.

Institutions are associated with positive attributes, but less so by the unengaged Jews

Overall, community organizations are most closely associated with working to help Jews in need and providing required help and support for Israel. Both these items had a mean score above 3 in 2019 as well as 2021. In addition, these institutions are not seen as generally unwelcoming specifically to Jews of color or members of the LGBTQ community. But, as explained below, there is still some expectation of these organizations to be more welcoming, more open, and more diverse.

A somewhat different picture emerges when distinguishing between the results by engagement. For the 60% who are not engaged in community activities, the scores are less positive and offer less differentiation. Among the unengaged, only “helping Israel” gets a score above 3.0, and only barely, indicating that it is at least descriptive of Jewish institutions and organizations.

Some of the biggest differences in how the unengaged and unengaged perceive community institutions on these attributes are representativeness, being too focused on Israel and too involved in partisan political issues. Still, even among the unengaged, the positives are generally more descriptive than the negatives, and the same items about helping Israel and Jews in need rise to the top.

Regression analysis reveals how these perceptions and other factors are connected to engagement. The single biggest predictor of engagement is synagogue attendance. The higher the level of synagogue attendance, the more likely Jews are to feel connected to community institutions and engaged with them. Among the synagogue members and engaged Jews, over half give money often, and many volunteer time. Parents with children at home are more likely to do so than those without.

The next strongest predictor of engagement, after synagogue attendance, is how well Jews feel that community institutions represent them and how much they see the organizations as too focused on Israel. The next most important factor that emerges from the regression analysis is “not open to members of the LGBTQ community.” The more Jews perceive the institutions as not open to LGBTQ participation, the less likely they are to be engaged.

Perception of Representation

Overall, 81% see the community institutions as welcoming, with 45% feeling that these institutions are only somewhat welcoming and 36% feeling that they are very welcoming. This lukewarm assessment is even more pronounced among the non-engaged, a majority of whom

Most see institutions as generally welcoming and representative to some degree

(54%) feel that community organizations are only somewhat welcoming – more than double the 25% saying “very welcoming.”

This estimation was slightly higher in 2019 (85%) than in 2021 (81%) but the drop is small and is not characteristic of any particular demographic. Non-denominational and Reform Jews are more likely to see the community as less welcoming. Over a quarter of the non-denominational Jews (25%) see the community as unwelcoming.

How welcoming do you feel Jewish institutions and organizations are to people like you?

Smaller donors are also less likely to feel institutions are very welcoming. Nearly two-thirds (64%) of those reporting annual charitable contributions over $10,000 see the institutions as very welcoming. That goes down to 44% of those giving $1,000-10,000 a year; and to 31% of those giving less than $100 a year.

In 2019, with a large enough sample size to look at many of the smaller, potentially marginalized groups, we found that contrary to natural assumptions they were relatively less likely to see institutions as unwelcoming. Less than one-in-ten Jews of color felt the community is unwelcoming, slightly lower than the 15% overall. The 39% of non-white Jews who saw the community as very welcoming is a point higher than Jews overall. Nearly half of Jews with disabilities (47%) felt the community was very welcoming and were no more likely than other groups to feel it is unwelcoming (15%).

In the 2021 survey, these demographics were less likely to indicate that community institutions are “welcoming.” The smaller sample restricts the ability to do much with subgroup analysis, but since this is a recontact survey of previous respondents, we can look at the results at the individual level.

Regarding Jews with disabilities, the changes were quite small and leaning only slightly toward negative. Five percent of the respondents moved into the response category of feeling the community institutions are welcoming, whereas 7% moved into feeling they are unwelcoming with a net shift of 2% — a small shift, in line with the 2-point negative shift for the entire community. For Jews of color, the change was slightly more significant, 7% toward feeling the community institutions are welcoming.

In general, these potentially marginalized demographics are no more likely to feel excluded than the community as a whole. As noted below, this is a community that places a premium on diversity, inclusion and openness.

Just over two-thirds feel community institutions care about what “people like you think about the priorities, policies, and activities of these organizations and institutions,” 19% feel the institutions care a great deal, with 50% feeling they only care “some.” A majority (54%) say the institutions represent their point of view well, but only 8% feel they do it very well.

On both these metrics, the engaged and the Orthodox Jews are more likely to feel positive but

A similarly positive response characterizes views on how much the institutions care about their views and represent people like them

not intensely so. Among those who are engaged, 85% feel that the institutions care about what they think, but only 32% feel they care a great deal. For the Orthodox Jews, the gap in intensity is even wider, with 91% feeling institutions care about what they think, but only 19% feeling the institutions care a great deal.

Only 10% of the non-denominational and the unengaged Jews feel that the institutions care a great deal, but 54% of the non-denominational and 60% of the unengaged respondents feel they do care at least some about how people like them think.

All of this shows that the problem for community institutions is not so much a negative perception, as just a lack of a strong positive identity. This finding indicates that there is room for improvement and a strong need for it.

Modes and Frequency of Participation in Communal Institutions

So far, defining engagement has been left to the perception of each respondent. A fuller picture emerges by considering the frequency and type of activities that make up that engagement.

Even for the engaged, involvement is limited primarily to contributions and holiday events

Types of Involvement with Jewish Institutions

By far, the most common forms of involvement in the Jewish community are making a financial contribution, reading publications and newsletters from Jewish organizations (both of which 52% said they do at least sometimes) and participating in religious or communal commemorations like Yom HaShoah or a Chanukah lighting (48%). Therefore, even engaged Jews are most likely to be involved in activities that require less commitment or time.

This is true across a broad range of demographic groups, although younger people and those reporting lower incomes are a bit more likely to volunteer their time than to make a donation. While non-denominational Jews exhibit similar tendencies in relative terms, they

are less likely to do any of these things. On average, those who are engaged take part in 5-6 of these activities at least sometimes. This includes more active participation in volunteering, serving on boards, or using the facilities.

Of the unengaged, nearly half (44%) do not take part in any of these activities with regularity. Only 13% say they give financial contributions often and only 11% read publications or newsletters often. For all the other activities listed, only single digits (2-9%) of the unengaged do them often. This is yet another example of how they may value their sense of Jewish identity, but not a connection to the community proper.

One of the changes in comparison to 2019 is a small increase in those saying they are involved through financial contributions, with a decrease in most other activities. The changes are slight but do put financial contributions at the top of the list of activities that the unengaged do often, along with the slight decreases in everything else from the use of daycare or other services, volunteering, or attendance at events. It is presumed to be the effect of the pandemic.

Few report any drop in giving during the pandemic

Only a few survey respondents reported giving less during the pandemic, even among those who claimed that COVID-19 hurt them financially. Nearly one in five of the engaged Jews gave more than before the pandemic. When asked about changes in their charitable contributions to Jewish institutions and organizations since the COVID-19 pandemic started, over 66% said that there was no change in their scope of giving.

Motivation for Engagement

The top motivations for involvement were to sustain the community for future generations and one’s family, and to maintain the connection for themselves. Antisemitism was an important reason for involvement, but few named it as one of the most important.

Although the sense of community may not be as important as the sense of Jewish identity, it was the most important motivation for being involved with Jewish institutions. In a list of reasons to be involved, the top two were the “desire to help sustain and continue the Jewish com munity for future generations,” which was very important for a 56% majority, and “wanting to keep a Jewish connection for yourself and your family” (very important for 54%).

Since the COVID-19 pandemic started, which of the following best describes your charitable contributions to Jewish institutions and organizations?

Other motivations relating to Jewish history and a sense of community followed with slightly smaller majorities. Thirty-five percent indicated that the desire to help Israel was an important reason for being involved. Generational motivation was ranked at the top by both parents and non-parents, and across all age and giving levels. It was also the top motivation for the engaged.

Reasons to be Involved

The top reasons for involvement are still sustaining the community for future generations and keeping

Ranked by % “One of the Most Important”

The graph above shows the attributed importance of reasons offered by some for being involved in Jewish organizations or institutions. Two notable differences emerged between the engaged and the unengaged. First, among the unengaged, none of the items rose to the level of very important for a majority. Among the engaged, all the items were very important for a majority.

Second, for those who are engaged, the top reason for involvement was that “history has shown that Jews need to take care of themselves.” This was very important for 43%, just ahead of sustaining the community for future generations. The historical imperative was more important for 67% of the engaged but ranked well behind the more positive reasons concerning continuity and future generations. Generational and personal connections ranked at the top across giving levels but were highest for bigger donors. For smaller donors, antisemitism was also a top motivation for involvement.

Reasons for not getting involved include time, other priorities, and politics, although those who are already engaged also cited lack of diversity. The most common reason given for not being more involved in Jewish organizations was not having the time or that they would rather do other things. Simply put, it was an issue of competing priorities. Many are disengaged by choice, and even substantial intuitional changes may not be sufficient to stimulate their involvement. Unengaged individuals were much less likely to perceive the institutions as representative and open, and more likely to see them as too focused on Israel, politics, or donors.

Thirty-two percent said that between work, family, and other obligations, they simply do not have time to be involved, and it was a very important reason for their lack of involvement in Jewish community organizations. Twenty-eight percent said that Jewish organizations were just not a high priority for them. The lack of time ranked at or near the top for those who were engaged already and those who were not. Among the unengaged, 36% said that being involved was not a priority, and 34% that they did not have the time. Lack of time was also the top obstacle for the engaged (29%); 17% of the engaged regarded involvement as a low priority for themselves.

Concern that the institutions were too political or too conservative was a problem across engagement levels, with 25% of the engaged and 26% of the unengaged citing “most of the organizations are too conservative for me on political issues” as a reason for not becoming involved. Political partisanship “here and in Israel” was a very important reason for not being involved for 23% of the engaged and 21% of the unengaged.

For individuals already engaged in Jewish organizations, lack of diversity was just as problematic as politics. Twenty-four percent of them said that “these groups are not open and welcome to new diverse voices such as those of younger Jews,” which was a very important reason for not becoming involved. Among Jews whose annual charitable giving exceeds $10,000, failure to welcome diversity was the single top reason for not becoming more involved in Jewish organizations. Thus, although the lack of diversity may not be keeping people from becoming involved, it is a concern for those who are already active.

The issue of diversity does not rank as high for respondents with certain demographic backgrounds who might feel excluded. For 18-39-years-old, Jews of color, and those with disability, it ranks near the bottom of reasons for not being involved. But as detailed below, these groups put a premium on diversity and favor taking steps to increase inclusion.

Inclusivity and Outreach

A majority believe that institutions should do more to be inclusive and in touch

By nearly 3:1, American Jews believe that community organizations and institutions should consider becoming more inclusive and in touch with the community. Sixty-four percent (a 4% increase since 2019) favor change, including 38% strongly in favor of it, compared to only 18% who do not want change.

The interest in change of those already involved in the community is even higher. Seventy-four percent of engaged Jews want to see such changes considered. This is also supported by a 51% majority of the unengaged Jews, whereas 25% have no opinion.

Support for change is higher among the younger (69%), non-white (57%), and those with disabil ities (75%) Jews. Support was below 50% among non-denominational Jews, over 60% among all denominations, and up to 72% among the Orthodox.

Three of the four proposals tested for this change were seen as at least somewhat effective by over 64%. The most attractive of the proposals we examined – bringing in more leadership from underrepresented groups – was seen as at least somewhat effective by 68%, and very effective by 29%. This was the top-scoring proposal across age groups, giving levels, and engagement levels, as well as with the Jews with disabilities and Jews of color. It was also top scoring across all denominations except the Orthodox, who ranked putting “more policies and decisions up to a vote of all members” as most effective (34% very effective). Even the least supported proposal was seen as at least somewhat effective by 44%.

The issue of diversifying the leadership of communal institutions was perceived as an effective way to increase overall inclusion within these organizations, across all age groups and denomi nations. Other suggestions supported by 20% or more were reserving leadership slots for vol unteers and putting up more decisions for a vote. These suggestions were welcomed by smaller donors, Jews of color, and Jews with disabilities.

Change is not the solution, however. Only 29% said they would get more engaged if “Jewish institutions made some changes and showed they cared about people like me.” Forty-nine per cent said that they were not going to become more engaged “…no matter how they change the leadership structure.” Again, those already engaged were more interested, with 31% saying that they would become more involved if changes were made.

Do you feel Jewish institutions and organizations should be considering changes to be more inclusive and in touch with the community?

Those who voiced an opinion gave their local organizations positive marks for dealing with the pandemic (over 43%), but just as many did not know how the organizations did. The engaged and Orthodox were overwhelmingly positive.

Did your local Jewish community do a positive job of dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic?

Connection to Israel

Israel has always played a role in Jewish communal life. This continuing role was accompanied by ongoing debate, which has become even more public in recent years. Despite all claims to the contrary, this survey shows that the bond between American Jews and Israel is enduring and strong. At the same time, there are cracks beneath the surface that merit the special attention of community institutions.

To start, the story is indeed more positive and unifying than is often reported. Despite the frequent stories about the gap between U.S. Jews and Israel, the vast majority of American Jews feel an emotional connection to the Jewish State and consider themselves “pro-Israel.”

Nearly two-thirds (64%) feel an emotional attachment to Israel. Attachment is slightly higher for seniors (68%). It is also higher for Orthodox (95%) and Conservative Jews (84%) than for Reform Jews (63%). Even among those with no denomination, 44% feel an attachment to Israel.

The majority of American Jews feel some emotional attachment to Israel, but few feel it strongly

Attachment to Israel

The level of attachment of non-denominational Jews dropped 12 points from 2019, when it was 56%. Although other demographics stayed fairly steady, the overall change was only 3 points going from 67% feeling attachment to Israel to 64% in 2021.

Another factor in the emotional attachment to Israel is whether they have been to Israel. Close to half (45%) of American Jews have been to Israel. Among those who have been there, 81% feel emotionally attached to Israel; and 45% say they are very emotionally attached. Among those who have not been there, half (50%) feel an attachment, but only 13% feel very attached.

There is also a notable difference in the level of attachment by engagement. Among those very engaged in the community, almost all (92%) feel some emotional attachment – including 72% who feel very attached. At the other end of the spectrum, among those not all engaged, just over half (52%) feel this connection with Israel, and only 14% feel a strong attachment.

Attachment to Israel by Level of Engagement

The direction of the causal link is not clear. The Jews engaged in the community could be more involved because they have a greater connection with Israel. Or it could be that their involvement in these institutions strengthens their attachment to Israel. It is likely some of both. This also ties back to the regression analysis noted earlier. The perception that institutions are “too focused on Israel” is not widely shared but is one of the strongest drivers of unfavorable views of community organizations.

Most American Jews (55%) say that “what happens to Israel will have something to do” with their lives. This percentage is even higher for the seniors (64%), Orthodox (84%), and Conservative Jews (75%), and for those who have visited Israel (66%).

Still, this connection with what happens to Israel is not nearly as strong as the 82% who feel that way about what happens to other Jews in the United States.

Over four in ten (44%) feel that what happens in Israel has little or nothing to do with their lives. Among younger and non-denominational Jews, majorities feel this way (54% and 61%, respectively).

A majority of U.S. Jews feel a sense of shared fate with Israel

In some ways, it could be expected that American Jews would feel that what happens to other Jews in the U.S. would have more of an impact than whatever happens in Israel. But it is a reminder that for some American Jews, Israel is not as close or immediate an issue.

An Israel Index using similar factors to the Jewish Identity Index also underscores this difference. Only one in ten (11%) are in the high index category feeling both very attached to Israel and that what happens to Israel has a lot to do with their lives. That is less than half the 25% in the high range of the Jewish identity index and shared fate with other American Jews category.

Knowledge about Israel

We used a simple three-question, multiple-choice quiz to gauge awareness of events in Israel. While this pop quiz is far from an ideal assessment of awareness, let alone understanding, it does provide an interesting gauge of how knowledge can differ by demographics.

Most were able to answer basic questions about Israel, but the less engaged and less attached to Israel were less informed. We asked three general knowledge questions about Israel to establish an Israel Identity Index:

How much do you think that what happens to Jews in this country/ Israel will have something to do with what happens in your life?

Those more engaged in the U.S. Jewish community appear to be more informed about events in Israel

• Who was the current Prime Minister of Israel? (multiple choice)

• Which city was home to the US embassy in Israel? (multiple choice)

• Were Arab citizens of Israel allowed to vote in Israeli elections?

Although many American Jews have some basic information about Israel, shockingly, four in ten do not know that Arab citizens have voting rights.

Responses to Multiple Choice Quiz

Each question was answered correctly by a majority or large plurality across demographic backgrounds. Those not feeling attached to Israel and smaller donors were correct less often. The engaged and observant were better informed, but even among the unengaged, a majority an swered at least two of three questions correctly; younger Jews were no less informed than the seniors.

Over three quarters (78%) of Orthodox Jews answered all three questions correctly, as did 52% of Conservative Jews, as opposed to 36% and 35% of Reform and non-denominational Jews, respectively.

There was a similar difference in community engagement. Among those engaged in community organizations, 59% answered all three questions correctly, compared to 35% of the unengaged.

Correct Responses by Israel Identity Index

The more informed were higher on the Israel Identity Index. Among those who provided correct answers to all three questions, 60% were in the top two tiers on the Israel Identity index. Among those who were least informed (0 for 3), 71% were in the bottom two tiers on the Israel Identity index.

Boycott Divestment Sanctions Movement

Nearly two-thirds have heard something about B.D.S., and nearly a third (31%) have heard a great deal. But over a third (37%) are unfamiliar with it, with 19% saying they have heard nothing at all about B.D.S..

Those familiar with the Boycott Divestment Sanctions (BDS) movement are opposed–many strongly–but not everyone is aware of the boycott

Nearly half of non-denominational (48%) and unengaged (45%) Jews said that they have heard little to nothing about it. Younger Jews are more aware of B.D.S., with 74% saying they have heard about it, compared to 57% of those over 40 years old.

How much if anything, have you heard about the Boycott Divestment Sanctions movement, or B.D.S., against Israel?

Do you support or oppose the B.D.S. movement against Israel?

(Asked only of those who had heard of B.D.S.)

Those familiar with B.D.S. are largely opposed: two-thirds (66%) are opposed, with 51% strongly opposed. Opposition is over 60% across age, engagement, and denomination – with the excep tion of non-denominational Jews who are just slightly lower at 58% opposed.

The opposition is strong, but not universal. Nearly one in five (18%) are unsure about it. Another

16% say they support the movement, although only 6% are strongly supportive. Younger Jews are not only more aware of B.D.S., but also more sympathetic, with a quarter (24%) supporting

Overall Support for Israel

The majority of U.S. Jews are pro-Israel but critical of some Israeli policies

An overwhelming 84% majority of American Jews identify as pro-Israel. This includes those who identify themselves as pro-Israel, but are critical of certain policies. Still, the near unanimity around being pro-Israel – even allowing for criticism – is worth noting. Across age, denomination, engagement, and political party over two-thirds identify as pro-Israel.

Which of the following best describes you? Are you...

Even among those unengaged in the community, 67% consider themselves pro-Israel. Similar majorities of the engaged (56%) and the unengaged (57%) Jews consider themselves pro-Israel but still critical of some Israeli policies. The difference is the level of uncritical support. Among the engaged, nearly a third (30%) are pro-Israel and not critical of Israeli policies, compared to 18% among the unengaged.

There is very little opposition or anti-Israel sentiment. Of those who are not pro-Israel, 8% are saying they are not sure or do not know, leaving only 8% identifying as “generally not pro-Israel”. This is slightly higher at 12% among both independents and non-denominational Jews.

Those identifying as pro-Israel increased slightly, going up 4 points from 80% in 2019 to 84% in 2021. There was also a slight shift from “pro-Israel and generally supportive of Israeli policies” which went from 23% to 19%. This was offset by a larger 8 point increase in “pro-Israel but critical” going from 57% to 65%.

The bigger movement is the shift by demographics and individual level changes. This is most likely in response to the Israeli elections and change of government which occurred months before the 2021 survey was conducted.

In the 2019 poll, taken when Prime Minister Netanyahu was leading the government, a 61% majority of Republican Jews were pro-Israel and generally supportive of Israeli policies. This is more than double the 27% who were pro-Israel but critical. After the election, Republicans were almost evenly split between pro-Israel and generally supportive (49%) and pro-Israel but critical of some, or most, policies (45%). The same sort of shift occurred among the Orthodox.

The shift among Democrats was not as large. But there was a decrease in those who were not sure and a 5 point increase in Pro-Israel but critical.

Looking at the individual level response shows more change than on any other indicator. Over half the respondents (51%) had some change in their intensity on the pro-Israel scale -- which includes moving from ”strongly” pro-Israel and generally supportive to “not so strongly”. The majority of that shift (29%) was becoming less strongly pro-Israel. The biggest shifters in that direction included include Republicans (34%), Orthodox (36%) and the engaged (33%). Among independent respondents 41% shifted towards less intense supportive positions, but this is a relatively smaller sample size.

Among Democrats there was shift in the opposite direction, actually changing categories – such as moving from pro-Israel, but critical of most policies to critical of some policies. One in five (20%) of Democrats moved category towards less critical support.

This large pro-Israel majority is similar to 2019, but there have been changes beneath the surface

This movement speaks to how much a change of government can affect American Jews views’ of Israel. This is particularly notable as the elections in Israel continue to come closer and closer to together.

United States Political Parties and Israel

While majorities see both U.S. Parties as pro-Israel, they see the parties going in opposite directions

Both parties are seen by large two-thirds majorities as pro-Israel: by 71% of Republicans and by a slightly higher percentage of Democrats (69%).

Fully half (50%) of American Jews see Republicans as pro-Israel and generally supportive of Israeli policies, compared to only 13% who see Democrats that way.

While Republicans are more pro-Israel than Democrats, they are also seen as more pro-Israel than American Jewry sees itself. As noted earlier, a 65% majority of American Jews identify themselves as “pro-Israel but critical of at least some Israeli policies;” three times over the 21% of American Jews who see the Republican party that way.

American Jews see Democrats as less pro-Israel than Republicans. They see 13% of Democrats as pro-Israel and supportive of most Israeli policies, but only 19% of them see themselves that way. Still, there is a big difference in how American Jews see the trends in each party. With so many seeing the GOP as supportive and uncritical of Israeli policies, it is not surprising that 39% feel the party is becoming more pro-Israel. This is fairly consistent across demographics. Even among Democratic Jews see the GOP as becoming more pro-Israel.

But it is in the Democratic party that people see the most significant change on Israel. A 54% majority of see the Democratic party as becoming less pro-Israel, including 26% who feel it is becoming “much less” pro-Israel. Again, some of this may follow from almost all Republicans (87%) feeling that the Democrats are becoming less pro-Israel. But even among Democratic Jews, a 44% plurality feel that the party is becoming less pro-Israel.

A 62% majority felt that their connection to Israel is about the same as it was two years before. One-third felt certain changes are evenly split between feeling their connection has become stronger (15%) or weaker (18%).

Across age, denomination, and engagement, most feel their connection to Israel is about the same. This is at majority levels across demographics, going slightly lower for younger Jews, 46% of whom say it is the same.

Younger Jews are slightly more negative about their attitude toward Israel, with 29% saying it has gotten weaker over the past two years, compared to 18% saying their connection is

Do you think the Democratic/Republican party is become more proIsrael, less pro-Israel, or not really changing its views on Israel?

A third of see the relationship between U.S. and Israeli Jews as weaker, although fewer think their connection has weakened

stronger. Among unengaged and non-denominational Jews, 19% and 17% say their connection has become weaker, with less than 10% saying it has become stronger.

For Orthodox, Conservative, and engaged Jews, the net change is more towards a stronger connection. For instance, among those engaged, 28% say their connection with Israel has become stronger, compared to 15% weaker; among the Orthodox Jews, it is 24% stronger and 18% weaker.

But while most American Jews feel their connection to Israel is unchanged, they are a little more negative about the overall connection between all Jews in the U.S. and Israel. A third (34%) of American Jews feel the relationship between Jews in the U.S. and Israel has gotten weaker. This is almost as many as those who feel the overall relationship is about the same (39%).

How does the personal connection you feel to Israel compare to what you felt two years ago?

This more pessimistic view of the overall connection is fairly consistent across demographics –although somewhat more pessimistic among the more engaged and the more observant. Among those engaged in community organizations, 40% feel the overall relationship has weakened, and 31% among the unengaged Jews. Fifty-two percent of the Orthodox Jews and 32% of the Reform and non-denominational Jews feel the overall relationship is weaker.

In 2019, the biggest concerns about the connection with Israel were driven by politics and politician’s personalities as driving policy. A 60% majority said that “Netanyahu’s support for President Trump and his policies” was a very important reason for feeling less connected to Israel; and 39% said it was one of the most important reasons for being less connected. The only other item where a majority said it was very important was “the increasing power of right-wing or ultra-religious parties.”

How do you think the relationship between Jews in the U.S. and Israel compares to what it was two years ago?

Reasons for feeling less connected to Israel center around the religious right and the treatment of the Palestinians, but concerns about the TrumpNetanyahu alliance still linger

“Settlement policies” (47% very important) and “treatment of the Palestinians” (45% very important) were also big factors. But clearly, the mutual support between Trump and Netanyahu struck a nerve and at least symbolized, if not embodied, deep concerns that present a risk for community institutions.

In 2021, with both Trump and Netanyahu having lost their re-election bids, the most important reasons for feeling less connected are the “right-wing or ultra-religious parties” (53% very important) followed by “settlement policies” (49%) and “treatment of the Palestinians” (46%). respectively).

Of those who said their connection to Israel had weakened over the past two years, over three quarters (78%) said that “the increasing power of the right wing or ultra-religious parties” was a very important reason.” Next were the settlement policies and treatment of the Palestinians which were cited as very important reasons for their weakening connection by over two-thirds (both at 69%).

But Trump and Netanyahu are still concerns for many. Nearly half (48%) said “the mutual support between Netanyahu and Trump when they were in office” was a very important reason for them feeling less connected to Israel. Among those whose connection had weakened, 67% said the Trump-Netanyahu was a “very important reason.”

Some of this is a reflection of the partisanship of American Jews: two-thirds (67%) of U.S. Jews identify as Democrats, compared to only 21% who identify as Republicans. Only among the Orthodox Jews there are more Republicans (57%) than Democrats (32%), but it is rather the exception than the rule. There are large Democratic majorities across age and engagement.

It should be emphasized that, in general, politics can be problematic for community institutions. In response to an open-ended question about what institutions could do to get people like you more engaged, the largest single group of responses (40%) centered on politics. Some said the institutions should stop moving so far right. Others said the organizations should stop moving left. Yet others said the organizations had become just too political. For organizations that want to be seen as institutions representing the community in a broad sense, politics carries more risks than benefits.

Conclusions and Next Steps

American Jewish communal organizations regard themselves as key players in building and sustaining a sense of identity and community, and take pride in being a central facet of the American Jewish community. They have spent decades grappling with increased threats to their sustainability and survivability. The increased vulnerability of Jewish identity in the United States, rising levels of assimilation of the younger generation, and questions of the relevance of Jewish communal organizations to contemporary Jewish life have all affected the strategies, programs, and activities of these organizations for years. The involvement in communal organizations may have the positive effect of increasing and deepening the sense of identification of those who participate, but it is not clear how well-positioned these institutions are to bring more people into the fold or even to strengthen the bond with those who are already engaged.

Although there has been considerable research on how Jews view their religious and cultural identity, not enough attention has been paid to how Jews relate to the institutions and organizations that seek to strengthen this identity and sustain a vibrant Jewish community across the U.S. The study findings presented throughout this report aimed to fill this gap, first, by providing an understanding of how American Jews perceive communal organizations and interact with them; second, by identifying the obstacles to increasing involvement; and last, by suggesting potential paths for strengthening the bond between Jewish community organizations and their members.

Several findings stood out and seem meaningful for charting a path forward for communal institutions and engaged Jews. First, it is evident that the issue of shared fate across all Jews, engaged or not, connected more or not at all. Our study provides some acknowledgment that a common bond exists despite everything. At the same time, although most Jews have some attachment to Israel, this connection is much weaker than what they feel toward fellow American Jews.

Second, our study suggests that, contrary to assumptions, Jews who belong to marginalized minority groups such as Jews with disabilities, Jews of color, and others were relatively less likely to see institutions as unwelcoming. In general, these potentially marginalized demographic groups are no more likely to feel excluded from communal institutions than the community as a whole. It is important to note, however, that the Jewish community places a premium on diversity, inclusion, and openness.

Third, the data clearly suggest that antisemitism is a major concern for U.S. Jews across the board. It is a higher concern for the more observant, older Jews, those with a higher identity index, and those who have personal experience of antisemitism. American Jews of all backgrounds share a concern over the rise in antisemitism in the U.S. Nevertheless, few are motivated by this concern to get more involved in community organizations.

Fourth, many Jews are disengaged by choice, and our findings show that even substantial intuitional changes may not be sufficient to stimulate their involvement.

Finally, when it comes to engagement, the time and resources Jews are willing to commit are decreasing. As our findings suggest, even the engaged Jews are most likely to be involved in activities that require less commitment or time, hinting at a change in patterns and types of engagement.

These findings and other details in this comprehensive report show that the main challenge for Jewish community institutions is not so much a negative perception, as just a lack of a strong positive identity. This finding indicates that there is room for improvement and a strong need for it.

In addition, our study shows that Jewish identity does not necessarily require involvement in Jewish communal institutions, potentially undermining the fundraising and programming approaches adopted by many of these institutions for the past decades, and possibly requiring the adaptation to new perceptions of Jewish identity and its measurement.

The implications of our findings are significant for those who are engaged with communal institutions but feel less connected and even marginalized. In particular, smaller donors, Reform Jews, young Jews, and Jews of color who are engaged with communal institutions could be better positioned and included in the leadership and decision-making processes of these institutions. For Jews already engaged in Jewish organizations, diversity is key for sustaining their engagement and enhancing their future participation and financial commitment. Failure to welcome diversity may affect not only these groups but also the engagement of medium-size and large donors.

A place to start the change would be a new (or renewed) commitment to diversity and inclusion. This can be achieved by reaching out to underrepresented, minority communities such as LGBTQ Jews, Jews of color, and Jews with disabilities. But this commitment can also include efforts to reach out to younger Jews, smaller donors, and others who have felt disenfranchised.

Jewish institutions must also be mindful of the risks associated with politics and policy. This is not a new issue, but the survey results show that divisive political issues had a particularly harmful effect in the last five years. There is no easy way to fix this, and it may be impossible to avoid politics altogether.