Week one: intro & being lost

‘The Beings’ was a series of online workshops led by writer Rosemarie Geary and artist Lucy Grainge over June/July 2021 as part of an online residency with Rumpus Room.

Rosemarie Geary gearyro@tcd.ie

Lucy Grainge lucy.grainge@outlook.com

Each session will include an introduction to the ideas and a space to reflect on them through music, writing and art prompts. No prior knowledge of these theorists is needed, the workshops are meant to be an accessible and enjoyable exploration of their work, we’ll figure things out together!

A note on the use of music:

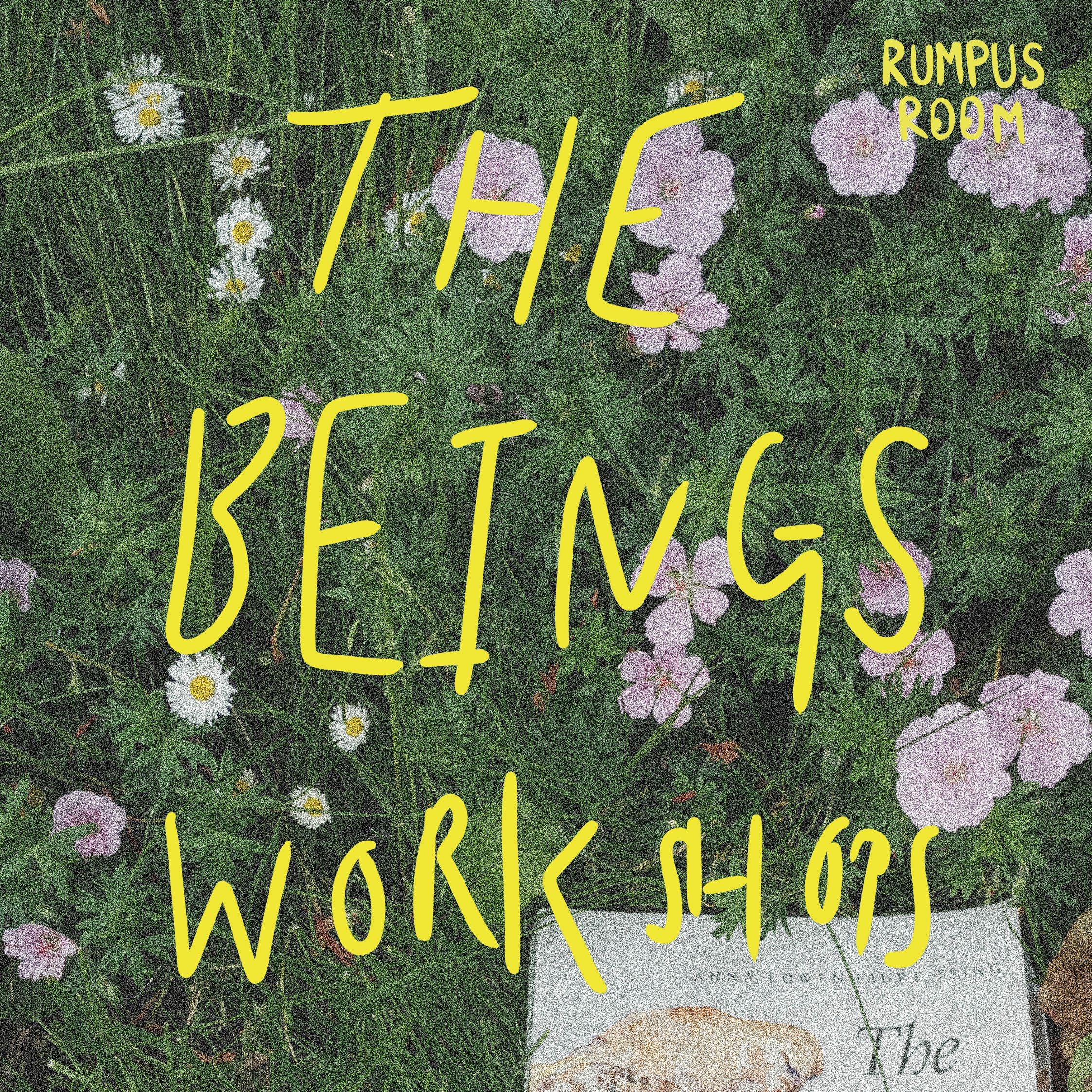

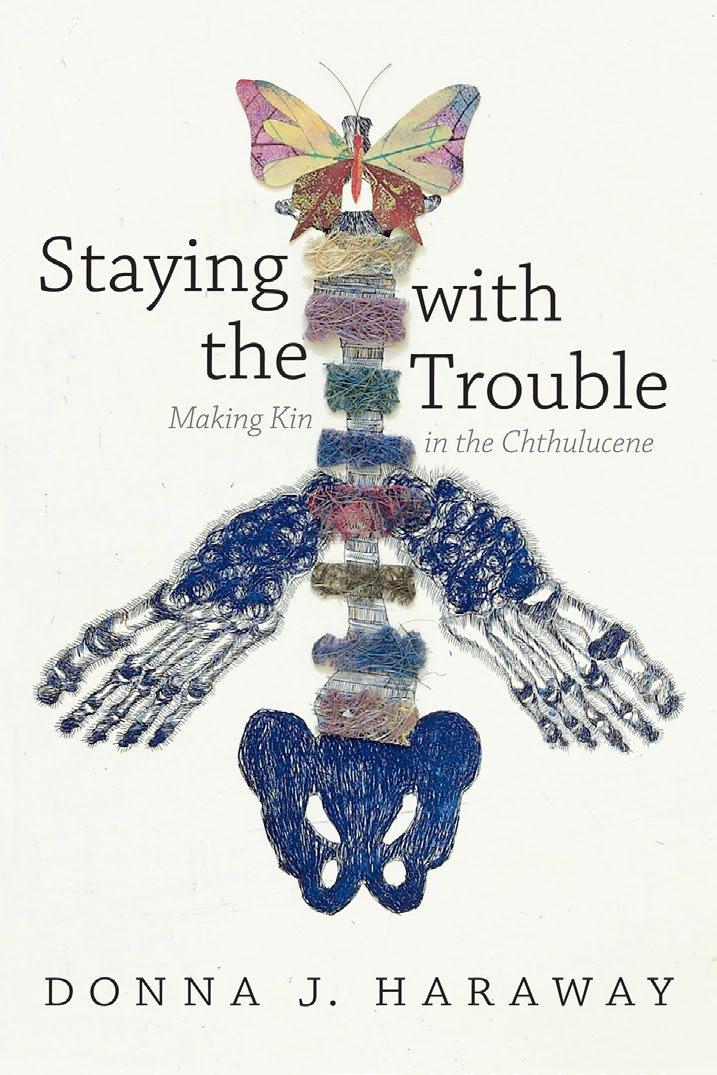

“In urgent times, many of us are tempted to address trouble in terms of making an imagined future safe, of stopping something from happening that looms in the future, of clearing away the present and the past in order to make futures for coming generations. Staying with the trouble does not require such a relationship to times called the future. In fact, staying with the trouble requires learning to be truly present” (Haraway, D. 2016, 1)

As someone who isn’t from a musical background listening to music makes me aware how difficult it is to actually be present, but when I manage to it’s incredibly rewarding.

These workshops are about finding our way back into the world we’ve inherited, and this can be a painful process. There’s always the temptation to look away, to escape to more pleasant realities than the one we’re faced with.

Even though most of us are visual creatures, sound is the sense that first tells us there’s a world outside of us. So much of our lives now are unconsciously taken up with tuning things out; noise pollution, a barrage of negative headlines, doom and horrific imagery. But disconnecting completely is a form of denial – we need to find good ways of tuning back in.

There are a lot of incredible musicians responding creatively to our times, who are using music/sound as a way of staying with the trouble. Each session will include an example of music that I think is achieving this. This will be a time to slow down and process, have a quiet moment, write or draw, or just sit and listen.

Introduction

A lot of the content is dense and difficult; exploring ways to think responsibly about climate change and reimagine our place in the world is always going to be an overwhelming process. If you do feel confused or overwhelmed, that’s totally normal and ok! Hopefully music will be a way for us to sit with what is difficult, and find some beauty/joy in it. Feel free to get in touch after sessions, ask questions etc. More than producing things, the workshops are a space for reflection, so we’d really encourage you to journal, take notes, draw pics, make mind maps, whatever works for you. If artwork is inspired by the sessions that’s amazing too, and we’d love to see it!

We are not experts and want to foster an environment where everyone feels comfortable to ask questions or contribute thoughts.

We will have a 10 minute break halfway through. If you need to have a further break at any point feel free to do so.

We will offer participants to read some text aloud to the group if anyone would like to do this, no pressure though – you can be as active as you like within the session.

Introduction

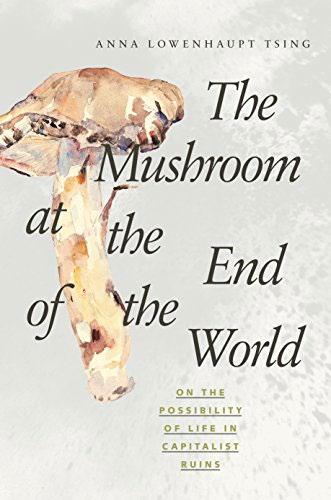

Books referenced

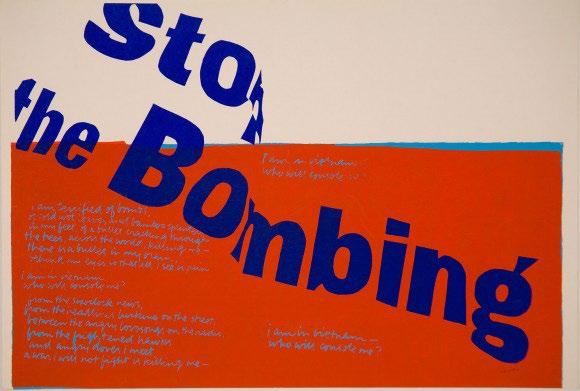

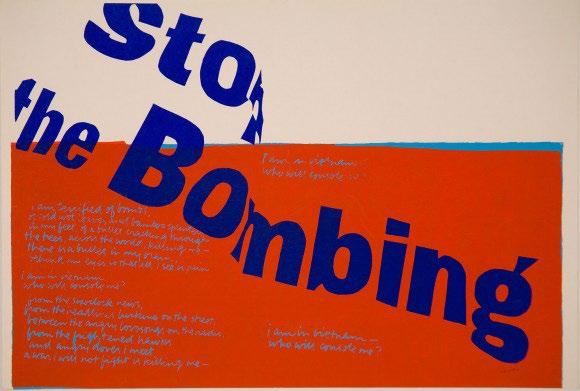

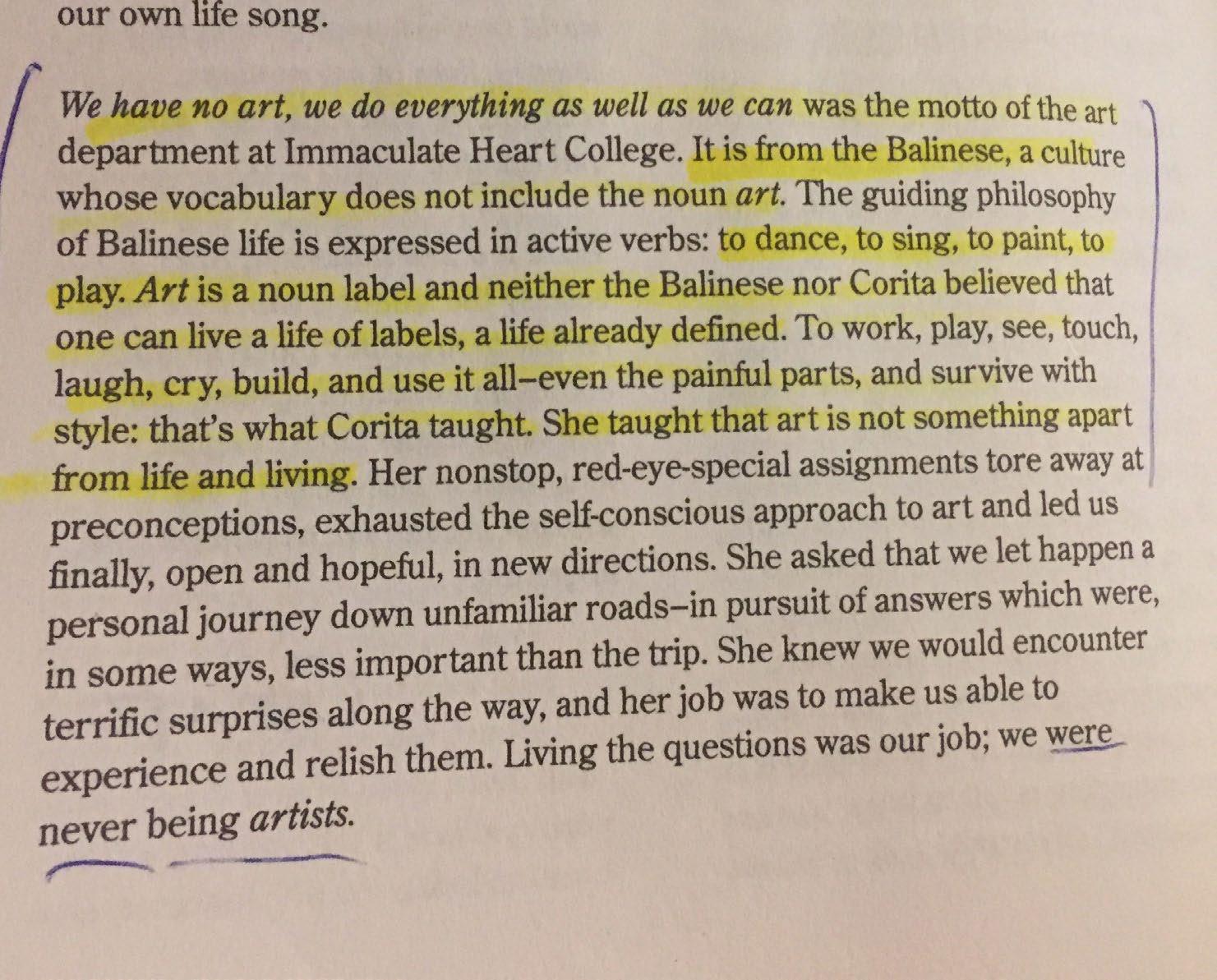

Corita Kent (1918–1986)

taken from Foreword in Learning by Heart: Teachings to Free the Creative Spirit by Corita Kent

Words became Images

(the following information is the same as the google map link - just formatted so easier to read)

1. Midway Atoll

Recognisable albatross fossils have been found that are 32 million years ago - millions of years before anything resembling humans walked the earth. These birds are now at the brink of extinction. Thom Van Dooren writes: Millions of years of albatross evolution - woven together by the lives and reproductive labours of countless individual birds - comes into contact with less than 100 years of human “ingenuity” in the form of plastics and organochlorines [industrial/chemical waste]… the impact of these toxic substances is felt almost entirely by breeding birds and their young; it is felt at the precise point where one generation brings forth the next. As shells break and young birds die, the next generation of albatrosses fail to fledge, and the knots that should bind the past to the future life of the species come undone.

But while these toxic products have a short past… their future is not limited in the same way. Rather there is something almost immortal about them… (2014, 31-33)

Week one: being lost

Photo: Chris Jordan, Message from the Gyre. Albatross corpse on Midway Atoll

The plight of the albatross captures some of the ways that our time seems unthinkable.

We’ve lost contact with nature, with the tangible beings and processes that give us life. Instead we’re surrounded and ruled by systems that seem huge and beyond our comprehension. Politics, economics, climate change itself, are abstract and multisystem processes that often feel too big to understand.

And when it’s boiled down to the simple reality of ecological destruction - it still doesn’t make any sense. We’re destroying our own home, damaging the conditions for life to grow and flourish.

It’s a time characterised by loss on such an immense scale its difficult to conceptualise; According to some biologists, we are now on a trajectory to lose somewhere between one-third and two-thirds of all currently living species. ( T. Van Dooren, 2014, 6 -7)

It’s not just futures and species but also languages, systems of knowledge, and ways of life that are being lost, both human and more-than-human. We’re losing ways of being that provided a sense of meaning, a way to orient ourselves in a shared and living world. In the face of this loss it’s no wonder that feelings of being uprooted and disconnected, being overwhelmed and confused are so prevalent.

2. Rumpus Room HQ

Three cases of lost language

3. Citizen Potawatomi Nation

i. Robin Wall Kimmerer, writer and botanist and enrolled member of the Potawatomi Nation.

European languages often assign gender to nouns, but Potawatomi doesn’t divide the world into masculine and feminine. Nouns and verbs both are animate and inanimate… [in Potawatomi there are] different ways to speak of the living world and the lifeless one. Different verb forms, different plurals, different everything apply depending on whether what you are speaking of is alive. (2013, 53)

There are only nine fluent speakers of Potawatomi left. RWK talks about leafing through her dictionary and finding the following words, nouns in English, in verb form; to be a hill, to be red, to be a bay… ... A bay is a noun only if the water is dead. When bay is a noun, it is defined by humans, trapped between its shores and contained by the word. But the verb wiikwegamaa - to be a bay - releases the water from bondage and lets it live. To be a bay holds the wonder that, for this moment, the living water has decided to shelter itself between these shores, conversing with cedar roots and a flock of baby mergansers. Because it could do otherwise - become a stream or or an ocean or a waterfall and there are verbs for that too… all are possible verbs in a world where everything is alive. Water, land and even a day, the language is a mirror for seeing the animacy of the world, the life that pulses through all things… (2013, 55)

In contrast is how we objectify nature, animals, trees, rocks and rivers in English; all are given the pronoun it. “ The arrogance of English is that the only way to be animate, to be worthy of respect and moral concern, is to be human.” (2013, 57).

Potawatomi is a language that situates the speaker in a living world. To lose it means losing a radically egalitarian way of seeing and relating to the world.

ii) This silencing, loss, uprooting is something shared not only across cultures but also species.

The Hawaiian Crow is extinct in the wild and reduced to 100 birds in captivity. These captive birds “are thought to have lost parts of their vocal repertoire in the absence of free-living adults to learn from” (T. Van Dooren, 2014, 133).

Hawaiian crows, writes Van Dooren, “likely share with other corvids a high degree of intelligence and a capacity for deeply social and emotional lives.” Crows have been known to console their mates after conflict, to recognise the mental states of others, and to exhibit what appears to be grief.

Without the songs and sounds - the language that, like our own, they have inherited from their ancestors, perhaps Hawaiian crows are also at a loss; struggling to express or communicate the experiences they were supposed to have learned from their parents; how to hunt, find a mate, map or defend their territory, express grief or warnings, or simply make their presence known.

4. Hawai’i - home to more endangered species per square mile than anywhere else on Earth

5. State of Bahia Brazil

iii. You’ve probably heard of the ‘wood wide web’: trees communicating and sharing information through a network of mycelia. Peter Wohlleben writes in The Hidden Life of Trees that this happens across all kinds of plant life, there’s even communication between different species, but in highly engineered monocultures there are no mycelial networks linking plants, the plants can’t speak.

Anna Lowenhaupt tSing writes of colonial sugarcane plantations in Brazil;

Sugarcane was planted by sticking a cane in the ground and waiting for it to sprout. All the plants were clones. [they came about entirely through farming/cultivation, they didn’t reproduce in the wild]. Carried to the New World, it had few interspecies relations. As plants go, it was comparatively self-contained, oblivious to encounter.

[Cane was planted, tended and harvested by recently enslaved Africans] who had no local social relations and thus no established routes for escape. Like the cane itself, which had no history of either companion species or disease relations in the New World, they were isolated… plantations were organised to further alienation for better control. (2015, 39).

Both the crop and the people that tended it were intentionally silenced and alienated, a practice that made them easier to subdue, and resulted, as tSing reminds us, in huge profits and power being made off the back of suffering.

By both design and unintended consequence, existence across cultures and species, lacks a sense of meaning and purpose, deprived of the language we need to reach each other, existence is alienated and lonely; features that make us, all of us, animal, plant, other - easier to control, categorize and subdue.

So what’s our task as creative people? How and what do we create in a time like this, a time of destruction. What does it mean to be the inheritors of loss, to listen and not understand?

The music this week is Almost Beautiful, by Anna Homler, who sings in a made-up language.

Music: Anna Homler, Almost Beautiful https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gd1OX9EEwYU

6. Atlantic

Ocean (At Sea)

7. Great Barrier Reef

Even in a technically ‘meaningless’ language, Homler found a way to make something beautiful, to communicate something that feels universal. It’s up to us to find our way back to each other, to create new ways of connecting.

As Anna Lowenhaupt tSing writes; “we don’t have choices other than looking for life in this ruin” (2015, 6)

There’s a scientist called Tim Gordon who recorded the sound of healthy coral reefs and played them at dead sections of the great barrier reef. The dead sections were completely silent, empty of the vibrant marine life that’s normally found in coral reefs. The sound attracted fish and all types of other marine life, re-establishing a living ecosystem, some of the fish feed on algae that takes over the coral, creating bare patches where the coral can begin to grow again. On its own it can’t solve the problem of the dying coral, but it’s a big step.

Amidst all this loss, there are still traces, and if we listen out for them, notice them, we can breathe new life into things.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eixMvMdF_cg

Tim Gordon ‘Helping Nemo Find Home’ - 3 Minute

Thesis 2017 Winner, Exeter University