9 minute read

Taking Action Why We Need to Design and Build With Carbon in Mind

from BC Focus fall 2020

by SAB Magazine

Why We Need to Design and Build With Carbon in Mind

By Lisa Conway

Advertisement

In recent years, human-centered design and biophilic design have been key initiatives in commercial architecture. In the industry’s mission to consider both how individuals experience a space and the effect of materials within the space, a building's impact on climate change beyond operational energy became an afterthought in some cases.

Today, the building sector is the world’s single largest emitter of greenhouse gases (GHGs), accounting for nearly 40% of total global GHG emissions according to the International Energy Agency. Experts say that carbon emissions from the built environment must peak within the next 15 years for Earth to stay below the global warming tipping point. Architects and designers in Canada and across the globe have an opportunity to help curb emissions in the built environment by specifying products that promote green chemistry, a circular economy and a healthier climate across the billions of square metres of new buildings and major renovations worldwide.

Buildings produce two types of carbon emissions. The first is operational carbon, which is defined as the carbon dioxide emitted during the life of the building, such as the energy used for heating, cooling and lighting. The second is embodied carbon, which is the carbon dioxide emitted as building materials are manufactured, transported and constructed.

The Interface office in Toronto. Interface is working toward being a carbon negative company by 2040.

It’s crucial that we reduce both emission types, but reducing embodied or “upfront” carbon is the most urgent opportunity as it stands today. Knowing that, architecture and design firms have an immense opportunity to push climate change initiatives forward by proactively working to reduce embodied carbon.

Through carbon-action organizations, such as materialsCAN, as well as careful research and strategic material specification, we can create spaces that produce measurable benefits backed by science. In fact, those specifying and manufacturing products for the built environment have the opportunity to create a positive impact on the planet and the health of society at large. Here are four strategies to keep in mind that reduce embodied carbon:

• Reuse materials, material waste and buildings whenever possible to eliminate the need to create new materials and construction. The use of recycled content does more than simply divert waste materials from landfills. By replacing virgin materials with pre- and post-consumer recycled content, manufacturers can reduce energy consumption, GHG emissions and more.

However, recycling isn’t only about what goes into products, but also what happens at end-of-life. In some cases, manufacturers will reclaim and recycle building materials through product take-back programs, so look for third-party verified programs to ensure products enter a closed loop system.

• Understand high-impact materials from a carbon standpoint and pay attention to the embodied carbon of those materials, including concrete, steel, wood, glass, insulation, carpet and more. In fact, there are new resources available that compare the amount of embodied carbon emitted by each potential product, such as the Embodied Carbon in Construction Calculator (EC3) tool.

The EC3 tool enables users to measure their project’s carbon footprint as well as compare and evaluate building materials that will help lower embodied carbon emissions. • Look for transparency documentation, such as Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) and Health Product Declarations (HPDs), on the products and materials specified. Take note of recycled and bio-based content as this can point to reduced embodied carbon.

Manufacturers should disclose this information about their processes, product contents and overall impacts on the environment and human health. However, it’s important to dig deeper and proactively ask manufacturers about their processes to better understand the strengths and weaknesses before specifying products.

• Engage and educate suppliers, partners and other vendors about embodied carbon and ask for their current and future strategies to reduce their carbon footprint. While this might seem like a moonshot strategy, purposedriven results are not beyond reach. For example, Interface founder Ray Anderson committed to making the company one of the most environmentally sustainable and restorative brands in 1994 – despite the negative impact that the carpet manufacturing industry was known to have on the environment at the time.

Today, Interface is working toward being a carbon negative company by 2040 by changing our relationship with carbon and using it as a resource and creating products and manufacturing processes that have a positive impact on the planet.

There is immense power in smart specification decisions and understanding what is behind the materials that we use in built environments. Sourcing materials that limit or reduce carbon emissions is a vital step, and manufacturers and specifiers must take action to reverse global warming.

Lisa Conway, Vice President of Sustainability for the Americas, Interface.

(www.buildingtransparency.org).

Copper Spirit Distillery

By Rafael Santa Ana

Located in the heart of Snug Cove on Bowen Island, a small municipality within Metro Vancouver, the Copper Spirit Distillery integrates an artisanal gin, vodka, and rye distillery with a tasting room and much needed residential rental units for islanders.

Focusing on sustainable production processes, the distillery incorporates rain harvesting and heat recovery systems. Connectivity with exterior light is critical in the project; natural light is harnessed even within the 10ft wide residential units and basement mixing rooms. The tasting lounge offers a side patio and a front patio which enhance the public infrastructure of Snug Cove.

By integrating the residential and industrial programs, the 8,815 sq.ft. building challenges both provincial code and local planning concepts. After numerous design iterations, the building evolved into two separate volumes connected by mechanical systems below grade and by a patio, with plans to transform it to a light-filled atrium, above grade linking the public spaces of the building.

The robust concrete shell remains exposed inside as a finish but is disguised at the exterior with wood cladding that evokes the local vernacular, and at the back with non-combustible phenolic panelling. The first building volume houses the public and residential areas. Three two-level rental suites sit above the tasting lounge, each with a private patio, views to the north, and skylights that allow natural light into the units. Visitors to the distillery are welcomed through the minimalist tasting lounge and out into a patio next to the south building which has large windows to showcase the German copper stills and the flow of the distilling process.

Within the second building volume, a clean concrete form contains the heart of the operation. The formal results and features of this space are shaped by the requirements of the complex mechanical systems involved in the distillation process. The state-of-the-art distilling equipment conveys simultaneously a steampunk and high-tech aesthetic.

The area perched above the copper stills accommodates mixing labs, workspaces, and access to the roof terrace, which is filled with herb plantings and offers stunning views of the village and cove. (Continues page 14.)

CLIENT Copper Spirit Distillery AREA 8,815 sq ft ARCHITECTURAL TEAM RSAAW Rafael Santa Ana, Antonio Colin, Larissa Llevadot, Vicente Castañon-Ruembe STRUCTURAL ENGINEERS Aspect Structural Engineers MECHANICAL / ELECTRICAL ENGINEERS Zoom Engineering Ltd. CODE CONSULTING GHL Consultants CONTRACTING West Coast Turn Key PHOTOS Andrew Latreille

1.The distilling equipment in the industrial south building conveys a steampunk and high-tech aesthetic. 2.The tasting lounge on the ground floor of the residential building looks out to the patio between the two buildings.

24

24

24 25

25

25 22 24

22

22 24

24

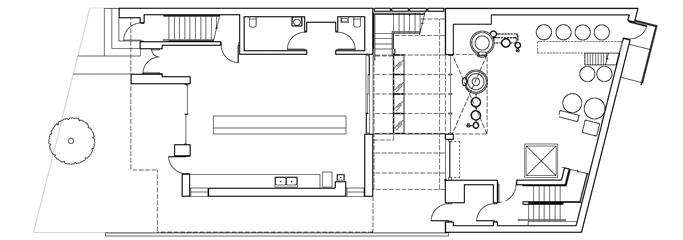

Third level

Residences

23

23

23

16

16

16

Second level

3

17 3

17 3

Residences

13

14 15

Ground level

North building

12 1 6 5

2

4

3

8

Tasting lounge

5 5

19

18

20

Mixing room

21

17

7

South building

9

10 11

Distillery room

1

Basement level

5 4

3

2

6

Floor plans

N

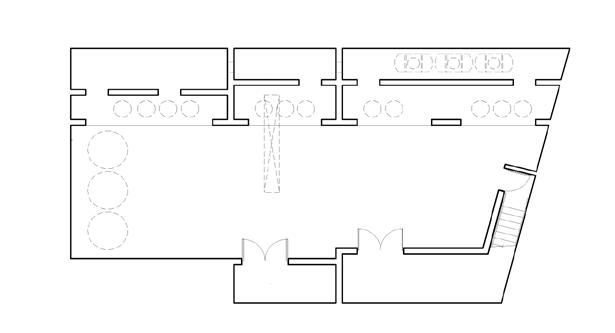

Basement

1 Rain Water Collection Chamber 2 Grain Storage 3 Aging Barrels 4 Water Treatment Shaft 5 Mechanical 6 Electrical

Ground,second and third floor

1 Entry 2 Tasting Lounge 3 Kitchen 4 Patio 5 WC 6 Storage 7 Atrium 8 Corridor 9 Distillery 10 Recycling 11 Stairs 12 Residence Entry 13 Residences Entry 14 Corridor 15 Emergency Exit / Balcony 16 Living 17 Stairs 18 Mixing Room 19 Viewing Corridor 20 Bottling + Storage 21 Office 22 Bedroom 23 Bathroom 24 Storage 25 Patio

3

3. Looking past the copper stills of the south building to the patio. A glass panel in the patio floor brings daylight into the storage and bottling areas of the basement. 4. The patio between the north and south buildings will eventually be fitted with an emergency staircase and glass roof canopy to form am open air atrium.

1. Water is collected from the North building’s roofs and then used in the distillation process

2. Social interaction between the building’s users and the public realm

3. Atrium glass floor brings light into the basement area

4. Energy produced by the stills to be used as an additional heating source

5. Grey water control

6. Roof garden juniper plantings for gin production

5. The north building at street level contains the ground floor tasting lounge and residential units above. The building company, West Coast Turn Key in West Vancouver, specializes in unique, logistically challenging or off-grid homes.

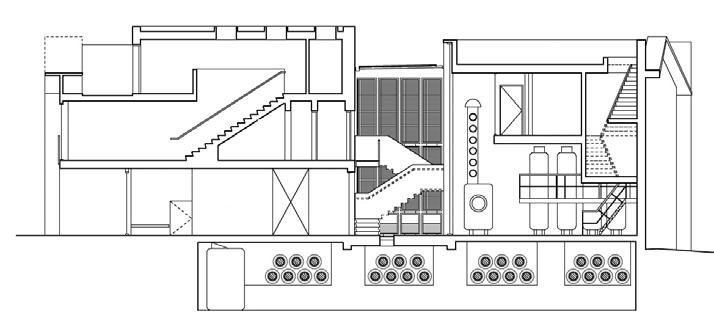

14

11

1 12

10

2

3 13

9 5 8

7

6

Section 4

Building section

1 Lounge Entry 2 Tasting Lounge 3 Rain Water Collection Chambers 4 Aging Barrels 5 Patio between buildings showing future configuration as an atrium 6 Still room 7 Mixing Room 8 Roof Garden 9 Corridor 10 Laundry / Storage 11 Living 12 Skylight Corridor 13 Patio and Storage 14 Washroom

A glass panel in the patio floor gives visitors a visual connection to operations and brings daylight into the raw material storage, bottling, and rainwater collection vessel area of the basement.

One of the distinguishing features of the facility is its extensive rain harvesting system that allows up to 15,000 litres of water to be captured, easily surpassing the 5,000 litres required per month operating at full capacity. For water discharge a rigorous approach that respects the municipal wastewater integrity is achieved by a three-phase process: sedimentation, temperature control, and PH regulation. The need for space heating is minimal as the distilling operation itself produces enough heat to maintain temperature levels at the upper floors.

The client’s holistic approach to the alchemy of boutique distilling remained a constant guide during the logistical challenge of constructing such a mixed-use facility on a small island. The result can be seen in the quality of the product and in the building’s overall operational success, from the large design gestures encompassing the visitor experience to the small details, including the ‘kintsugi-style’ healing of the concrete floor cracks with copper rivulets.

RAFAEL SANTA ANA IS THE PRINCIPAL OF RAFAEL SANTA ANA ARCHITECTURE WORKSHOP (RSAAW) INC. IN VANCOUVER.