7 minute read

SAA: When the wings came off.

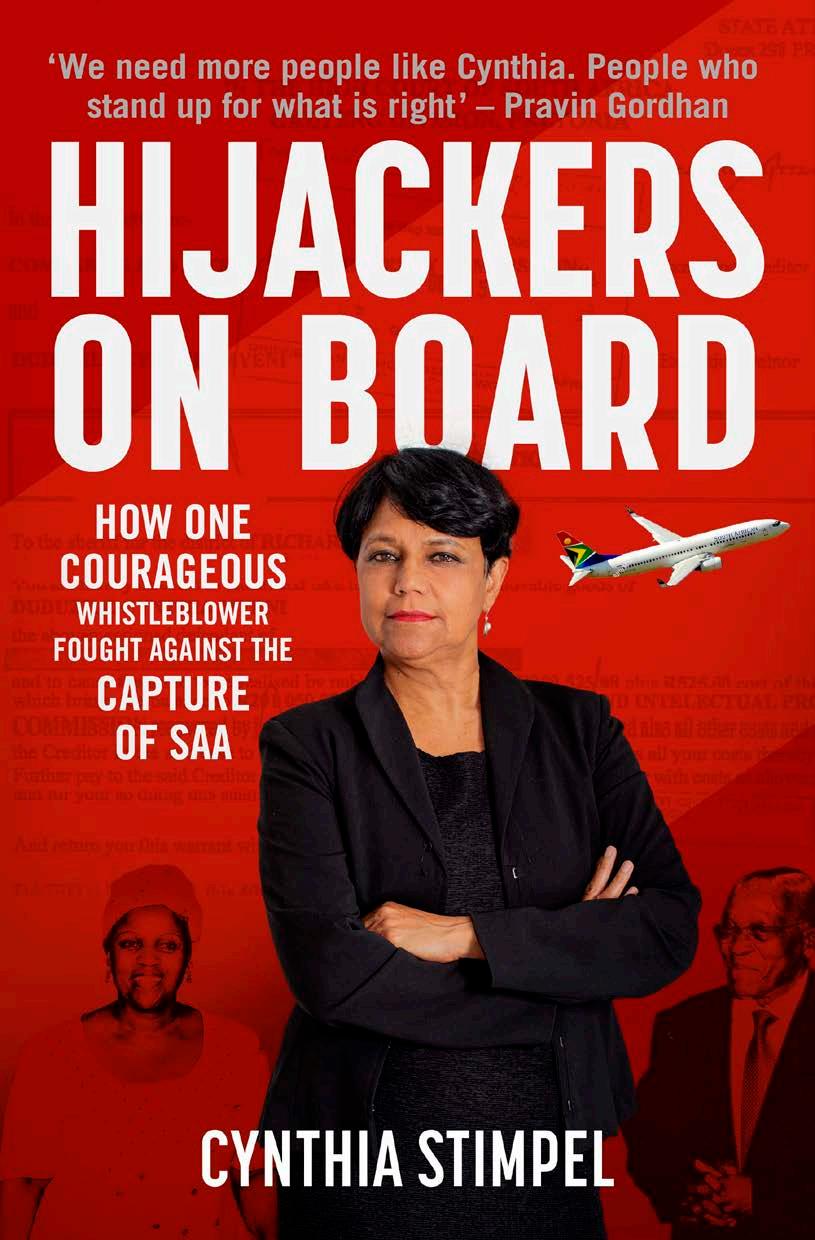

I have just read Cynthia Stimpel’s book, Hijackers on Board – about her having blown the whistle about Dudu Myeni and her cronies. It makes depressing reading, but what is clear is that 2015 was the year it really all went down the drain. As the SAA Group Treasurer Stimpel sheds new light on two infamous episodes on the airline’s history.

THE APPALLING DUDU MYENI had become Chairperson in 2012 and by 2015 had deployed her cronies into key positions of power. From the Zondo Commission and Stimpel’s book, it’s evident that the Acting Chief Financial Officer Phumeza Nhantsi was complicit in two big attempts to loot the airline – to hijack the R15 billion Airbus deal and the plan to use consultants to consolidate SAA’s R15 billion debt while sucking off R300m in fees, despite SAA having a more than capable treasury function to do the job.

As a South African state-owned airline, SAA was never going to be profitable as it carries a development burden – to provide job opportunities and to fly South Africa’s flag on uneconomic routes. Yet, with a modicum of honest and competent management it was able to limit its losses to around about one billion rand per year.

One of Myeni’s key objectives was the complete racial transformation of the airline’s management. It soon became clear that the experienced and skilled white managers were no longer welcome, and there was a rush of scarce skills for the exits.

The problems of skill loss and the promotion of incompetents has already been thoroughly covered. It is sufficient to say that the enforcement of the policy created a vast cadre of ignorant and toxic management. As I wrote as far back as 2008, the new appointees ‘wandered dazed and confused in the corridors of Airways Park’. Because the newly empowered could not do their jobs, they resorted to political turf wars, empire building and appointing cronies to protect their backs.

As noted, 2015 was the year the wings came off, with the losses ballooning from around R1 billion to R6 billion per year. One of the prime reasons for this jump was the now infamous view Myeni had the hubris to announce to her board and senior managers; “It’s our turn to eat now.”

Her strategy relied on a procurement policy which government had expressed as an ideal, but knew better than to try force on struggling state owned enterprises. However, Myeni made it open season for the rape of SAA procurement. Suddenly there was a rash of middlemen with BBEEE credentials inserted into the airline’s procurement process. And these middlemen were free to inflate prices to obscene levels. In the words of Vuyani Jarana, the first CEO to be permanently appointed since Monwabisi Kalawe in 2013, this opened the door to, “a culture of malfeasance” – without consequences. It was open season to torpedo SAA's already badly holed bottom line and thus sign the airline's death warrant when Covid hit.

Dudu Myeni stood up Sheikh Al-Maktoum three times - an unforgivable insult to one of the world's most powerful men.

It is an old truism that a fish rots from the head and I would go so far as to say that if you were an SAA manager who did not follow the lead of Myeni, (and ultimately Jacob Zuma), to loot your employer, you were considered stupid by your peers.

An investigation by Ernst & Young found that 60% of all procurement by the SAA group was suspect. A forensic examination was conducted on 48 corrupt contracts and when Myeni was subsequently grilled about this, she deflected the blame onto management, with not even a rueful acknowledgement that it had been her procurement policy which had allowed it in the first place.

Myeni went out of her way to sabotage deals, perhaps purely out of spite to those managers who had the courage to resist her. The final straw was her sinking of the Emirates partnership deal.

In January 2015 Emirates approached SAA with a proposal for a much-enhanced partnership agreement that went far beyond the existing codeshare. The then acting CEO, Nico Bezuidenhout, reckoned that this would have guaranteed and extra U$100 million revenue for SAA each year, using mainly Emirates ‘metal’ (i.e. planes). SAA would save millions in not actually having to operate unprofitable flights. At the then rate of R1 billion losses per year the deal could probably have achieved the rare feat of making SAA genuinely profitable.

Emirates already had a successful track record with these partnership agreements. A case in point is Qantas, which like SAA, had a codeshare with Emirates. To more fully understand how this would have enormously benefitted SAA, replace ‘Qantas’ with ‘SAA’ in the quote below from the original press release.

Qantas CEO Alan Joyce said, “The first five years of the Qantas-Emirates alliance has been a great success. Emirates has given Qantas customers an unbeatable network into Europe that is still growing. We want to keep leveraging this strength and offer additional travel options on Qantas, particularly through Asia.

“Our partnership has evolved to a point where Qantas no longer needs to fly its own aircraft through Dubai, and that means we can redirect some of our A380 flying into Singapore and meet the strong demand we’re seeing in Asia.

“Improvements in aircraft technology mean the Qantas network will eventually feature a handful of direct routes between Australia and Europe, but this will never overtake the sheer number of destinations served by Emirates and that’s why Dubai will remain an important hub for our customers.”

Sir Tim Clark, President of Emirates Airline, said: “The Emirates-Qantas partnership has been, and continues to be, a success story. Together we deliver choice and value to consumers, mutual benefit to both businesses, and expanded tourism and trade opportunities for the markets served by both airlines. We remain committed to the partnership. Emirates has worked with Qantas on these network changes. We see an opportunity to offer customers an even stronger product proposition for travel to Dubai, and onward connectivity to our extensive network in Europe, Middle East and Africa. Customers of both airlines will continue to benefit from the power of our joint network, from our respective products, and reciprocal frequent flyer benefits.”

The benefits to SAA of such a deal were truly inestimable. The financial benefit was expected to be R1.5 billion, but it would have taken SAA to the next level and made it an international player of real weight – and not just a struggling end of the line carrier on the end of a spoke from the Dubai hub.

Beyond the R1.5 billion revenue improvement, Nico Bezuidenhout told me that the heightened codeshare relationship would have many other benefits for SAA: for example, SAA would be able to cancel the loss-making Abu Dhabi sector that it was forced to operate to maintain its relationship with Etihad. He also pointed out that the Emirates deal would have been great for SAA’s pilots as it would to have enabled them to fly for Emirates when there was not enough demand from SAA. Plus they would have shared knowledge and training facilities with the huge Middle East airline.

Cynthia Stimple’s book shows that there were no less than three different signing opportunities with Emirates that could have given fantastic publicity to SAA: However, all three had to be cancelled because of Myeni's failure to just sign the deal’s Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) off.

The first attempt was on 5 May 2015 at the Arabian Travel Market in Dubai where Myeni was to meet Sir Tim Clark, the CEO of Emirates and Sheik Ahmed bin Saeed Al Maktoum, Chairman of the airline. Yet at the last minute she called in sick and then sent a letter to Al Maktoum stating that pressing commitments and unforeseen circumstances prevented her from attending the signing.

It is just not acceptable to stand-up the chairperson and CEO of the largest airline in the Middle East. SAA had egg all over its face.

Then, a week later, on 12 May, Sir Tim Clark visited Cape Town and personally invited Myeni to a meeting to sign the MoU. But once again she stood him up. The third occasion was at the Paris Air Show where Nico Bezuidenhout tells me she phoned him at midnight on the night before the signing and threatened that Nico and his wife Glynnis (who also worked for SAA) should not return to South Africa if the MoU was signed. In his long history in the Middle East, with its common practice of political meddling in business, Tim Clarke had seen this movie before and expressed his sympathy to Bezuidenhout. But after three attempts, Tim Clark told Bezuidenhout that the deal was off the table.

It is hard to understand why Myeni was so intent on sabotaging this lifesaving deal for SAA. In the absence of any other reason, I can only assume it was pure childish spite on Myeni’s part, as she didn’t want Bezuidenhout to succeed and was prepared to sacrifice the entire airline to that poisonous end.