9 minute read

The Origins of South African Flyfishing - Ian Cox

Title written by First Second Name Photos: other name The Origins of South African Flyfishing Ian Cox

It is widely believed that flyfishing came to South Africa with the introduction of trout in the 1890’s and that it was impossible to catch yellowfish on fly before the invention of the TVN nymph. But nothing could be further from the truth.

Advertisement

Bill Hansford Steel writes tantalisingly of flyfishers targeting native fish in the late 1700’s but does not cite a source for this statement. Craig Thom who has a talent for close research tracked down a reference in Lord Sommerville’s journal to an attempt to catch yellowfish on fly on the Reit River in 1801. Craig has tracked down where they fished and he and his daughter have caught yellowfish on fly at that location.

That, of course is a story in and of itself which we hope that Craig will publish one day.

But there should be nothing surprising in this. We know the English were avid anglers and that fly fishing was already popular in the United Kingdom at the end of the eighteenth century. The first British occupation began in 1795 but Englishman started arriving in the Cape before that. My wife’s ancestor, for example, came out in 1791 as an English teacher and settled in Swellendam. While history does not relate whether he was a flyfisher, he was of a class and came from a district where flyfishing was already popular in Britain. Officer’s in the army travelled nowhere without their guns and their fishing rods. Many of these would have been fly rods.

The early history of flyfishing in South Africa was all about targeting native species such as yellowfish, witvis and kurper. As Bertie Bennion pointed his book The Angler in South Africa that was published over a century later these fish were targeting by what he called ground fishing as well as flyfishing.

According to Hansford Steele traditional English flies of that time such as the Greenwell’s Glory and the Black Gnat which were brought out in the luggage of travellers rather than being specially imported. Both he and Bennion were of the view that flytying only began in the 20th century. But one must question whether this was indeed so. After all Canon Pennington was encouraging boys to take up flytying as early as 1909.

His book Trout Fishing for South African boys suggest a robust make your own culture that was already in existence in the early 20 th century. According to him a boy with a pocketknife, a few hooks and a ball of string and a bit of ingenuity could achieve much. You made your own kit or did not fish. It was what he did as a boy in the North of England.

“And the first trout”, he exulted, “a lively fellow rising beyond a bed of weeds under the shadow of the old grey church, caught with a home-made fly on a self-knotted, selfselected horse hair caste, was to me the bursting of a bud that grew into a strong branch on a sturdy tree.”

And it was not only the end tackle that was home made. Rods were also home made with the pieces splined and bound together with waxed string. “Metal joints, ferrules as they are called, were never used in our parts fifty years ago.” As for lines well you made your own out of horse hair and his book contains detailed instructions on how to do this.

He was equally robust on the subject of fly tying. Yes there were famous English patterns tied using the feathers of English birds but according to the good padre local feathers and locally tied flies did just as well and often even better than the professionally tied imports brought from home.

So, while our literature bestows the title of South Africa’s South Africa’s first indigenous fly on the “Kom Gouw” (circa 1859) it is likely that South African flyfishers were quietly tying their own much earlier than that. This after all what was any half decent northerner would do back at “home”.

I think it far more likely that the Kom Gouw and Fred Kerr’s Special which he designed on the ship out to South Africa and which closely resembles the Kom Gouw owe their fame to the fact that they were also used to catch trout.

There is much speculation as to why trout were introduced given that the yellowfish and witvis both offer very good sport. Wardlaw Thomson suggests that this was because anglers wanted to target fish from home, but I think his observation that South A f r i c a ’ s f re s h w a t e r f i s h e r y w a s n o t economically viable gets much closer to the truth. Then as anyone who fishes for yellows will tell you; they are not that good eating and can become very difficult to catch. They don’t hang about like trout do and are much more skittish.

Bringing trout to South Africa and successfully introducing them into South Africa’s rivers was a very expensive business. It took over two decades to get right. There has always been a strong commercial purpose behind the introduction of trout into South Africa. This investment was expected to pay dividends.

The Boer War got in the way of this venture, but things began to take off thereafter. Trout fishing became organised with clubs and farmers offering fishing and hotels the necessary accommodation. The Trout Bungalow was taking visitors by 1907 as were hotels in Nottingham Road and Rosetta.

J Spranger Harrison in the 1940's

So, it should come as no surprise that books began to be published extolling the magnificence of South African trout fishing. The first was Dumaresque Manning’s Trout Fishing in the Cape Colony published in 1908 followed the next year by Tetlow’s Fly Fishing

in Natal.

This was reproduced almost word for word in the Natal Descriptive Guide and Official Handbook that was published by the South African Railways in 1911. Interestingly I also have the 1895 copy of this guide which makes no reference to freshwater angling trout or otherwise. All these publications all heavily promoted trout fishing to the foreign visitor so it is not that surprising that they were told that the South African trout would rise to the tried and trusted favourites of their British

Wardlaw Thomson’s 1913 book The Sea Fisheries of the Cape Colony is the exception in that it does refer to fly fishing for native fish. But this was a more scholarly work aimed at describing the fishery rather than promoting recreational fishing. The new trout fishery comes in for a lot of attention, but he does mention in passing that yellowfish rose readily to the fly.

The rising popularity of trout fishing did not bring an end to targeting native fish on a fly. This is probably because trout fishing was an expensive pursuit in the years before the war regardless of what Pennington may have said to the contrary. A trip to the trout bungalow from Johannesburg to the Trout Bungalow took involved an 18 hour train ride to Nottingham road followed by a ride of a further 2 and a half hour ride weather permitting.

It would take you longer by car assuming you were one of the wealthy few who owned such a conveyance. Accommodation would set you back just over 9 shillings a week which was then the equivalent to the day’s wages of a skilled tradesman in Britain.

Trout fishing trips were special affairs. Unless you lived on the doorstep of a trout fishery your normal fishing was likely to be targeted at native fish found closer to home.

This all changed after the first world war when transport became much cheaper. That said flyfishing for native fish was still very popular in the 1920’s and 30’s. Indeed, Bertie Bennion’s marvellous 1923 book the Angler in South Africa devotes a whole chapter to fly fishing for yellow fish and what he has to say is as valuable today as it undoubtedly was then.

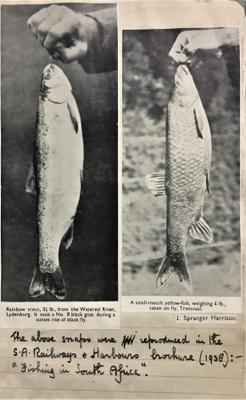

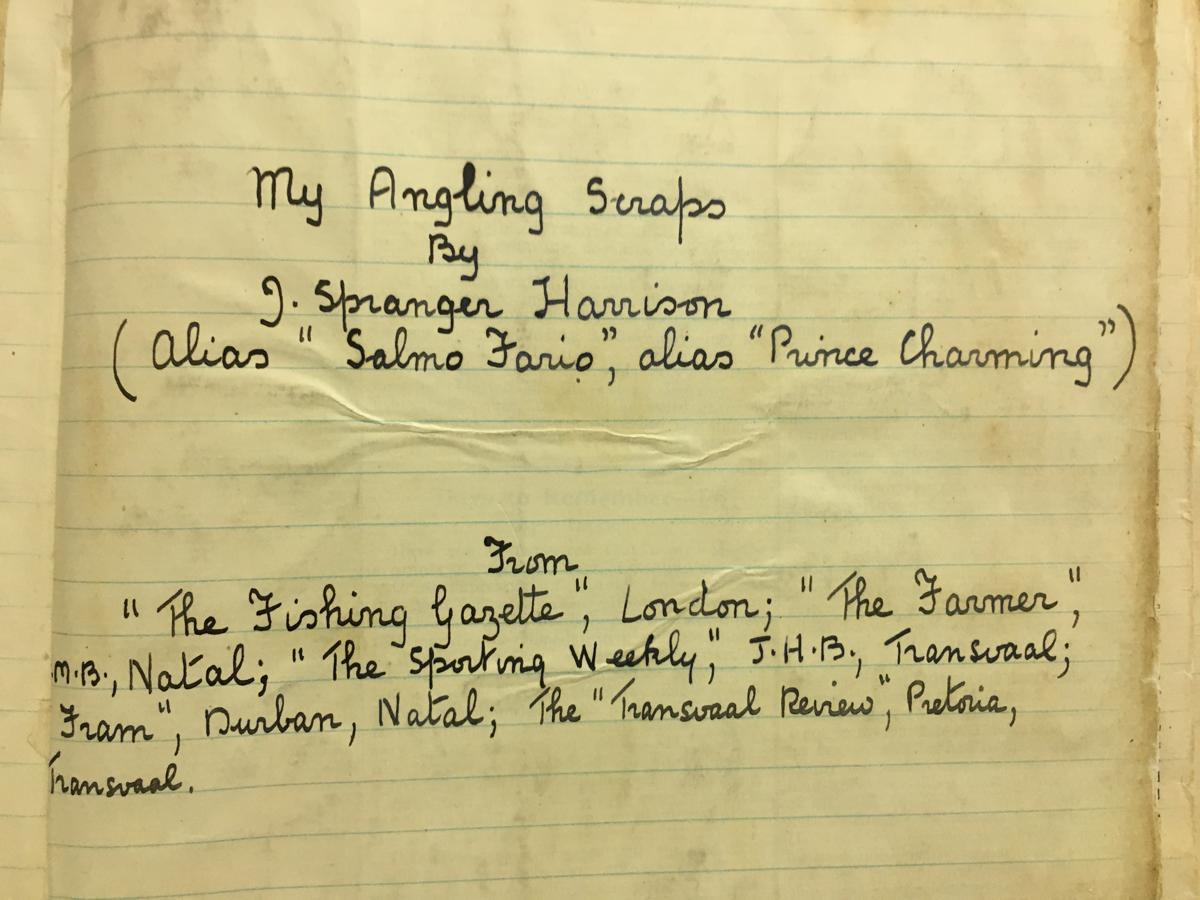

Next to nothing else was written in book form about fly fishing trout or otherwise between the wars that did not come from Bennion’s pen. But a great deal was written in periodicals that were published in this country and abroad. Bennion wrote much of the earlier stuff which has still to be collated. However, Spranger Harrison kept a scrap book of his writings in the 1930’s which I have been privileged to read. He writes extensively of targeting yellowfish and other native fish

For example, in 1934 he writes of catching a ten pound barbel on a black gnat and a two and a half pound yellowfish hen on an Invicta. It may have been nearly 100 years ago, but this passage still resonates:

“It is a rare occurrence, I should imagine, to become positively sated with fly fishing for any species of fish. It must be almost unique to become sated with fly fishing for smallmouthed yellowfish. Yet, such was my experience on the occasion I am writing of.

I commenced fishing at 6.15 p.m., just as the kurper were finishing their late-afternoon rise. I did manage to hook one splendid little halfpounder that fought gallantly before succumbing. Then the yellowfish appeared.

A perfect evening !

The swallows and martins were flying low, ever and anon swooping towards the water. For millions of gnat-like insects were sailing merrily over the placid surface, blown hither and thither by the gentlest of zephyrs. Fish were rising all around, feasting with utter abandonment, and apparently wholly forgetful of their life's teaching; '' Safety First."

I dropped my fly into the huge ''bell" made by the head-and-tail rise of a big fish. Instantly a dark torpedo-like streak flashed from the depths, but fish and fly never connected. The. former reached the latter, but, for some unaccountable reason, refused it. There was a mighty swirl, a golden flash; and in the fraction of a second the suspicious fish had disappeared whence it came.

With that one exception, I did not miss a single fish, and they rose at nearly every cast. Between 6.25 and 7.45pm I caught thirty-two. Most of the fish were small, running 4 to 6oz • a dozen weighed between 8 and 12oz., one scaled at 1 ½lb. I returned all to the water with hopes of renewing my acquaintance at a later date when they had matured”.