3 minute read

Freedom for the Prisoners

The New Zealand Salvation Army grew up amidst the depression years of the 1880s. Social distress was taking root, as unemployment soared and slums began to emerge. Poverty, addiction and immorality were rampant. Men went to prison, in and out, in a cycle of imprisonment that was not just physical but mental, social and spiritual. In 1884, the newly established Salvation Army responded by forming a Prison Gate Brigade to help reverse this trend.

In his book, Dear Mr Booth, John C Waite writes, ‘Booth’s Army was an “Army of the Poor”, and he was resolved to assist the destitute, not as one graciously condescending to them, but as one who believed himself to be their brother. The worst elements in the community were to be treated as if they were potentially the best.’

In 1883, en route to set up The Salvation Army in New Zealand, two young Salvation Army officers— Captain George Pollard and Lieutenant Edward Wright—made a stop in Melbourne, Australia on their long and arduous journey from London, UK to Dunedin. Pollard spent time there with Major James Barker who was working to reduce the recidivist criminal activity of ex-prisoners by meeting them on release and arranging accommodation and employment. Barker’s work was deemed so effective that magistrates in Melbourne sentenced some offenders to The Salvation Army ‘Prison Gate Home’ instead of sending them to prison. This practice was later adopted in New Zealand when Pollard opened the first ‘Prison Gate Brigade’ in Auckland in 1884, modelled on Barker’s success.

Brigade members literally met prisoners as they passed through the prison gates upon release. While many were taken directly to pre-arranged accommodation and employment, others had nowhere to go and no money. The brigade helped these newly freed but destitute men find employment, but their ex-prisoner status was a frequent barrier to finding appropriate accommodation. This frustrated Pollard who then determined that The Salvation Army would feed and house these men until accommodation and work were secured.

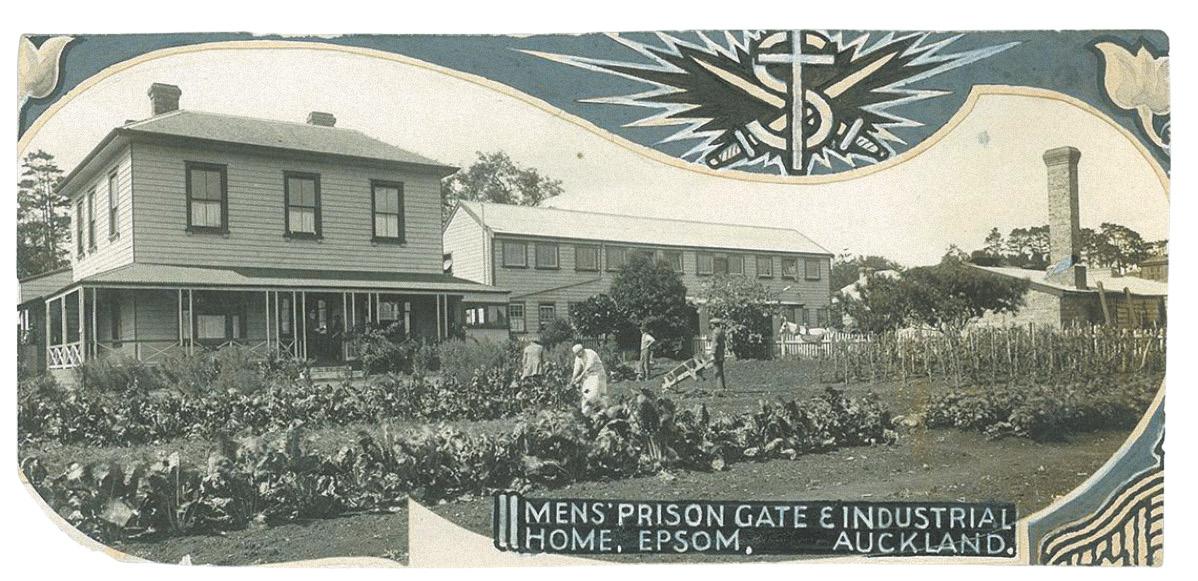

Captains Albert and Sarah Burfoot were therefore appointed to the task of caring for these men with the first Prison Gate Home opening in 1884. However, the four-bedroomed house was soon deemed totally inadequate in size, and a larger 10-bedroom building was secured near Queen Street. Figures from 1890 reflect the nature of the demand, with 310 men accommodated that year.

While results were mixed—only approximately 30 percent of the men were described as having gone on to be ‘reinstated as good citizens’—the Army’s work in helping discharged prisoners was nonetheless noticed. Police, magistrates and judges observed fewer repeat offenders, and, in 1887, the Minister of Justice paid tribute to the work of the Prison Gate Brigade in bringing about ‘the moral regeneration of men who had come to be regarded by so many as social outcasts’.

Furthermore, the Prison Gate Home began to serve as a relief centre for destitute men, serving meals and providing accommodation to relieve the economic need which so often led desperate men to commit crimes. In 1897, the Prison Gate Home moved to Margot Street in Epsom. Today ‘Epsom Lodge’ continues to provide transitional and emergency accommodation for men and a small number of women, and is currently undergoing a major refit.