4 minute read

Thinkaloud

The poetry of the psalms

WORSHIP is in full swing at Trend Contemporary Church as the band leads the congregation in lyrics written by Martin Nystrom in 1984.

As the deer pants for the water So my soul longs after you. You alone are my heart’s desire And I long to worship you.

Meanwhile, down the road at St Trads, the congregation sings similar words by Nahum Tate and Nicholas Brady first published in 1696.

As pants the hart for cooling streams, When heated in the chase, So longs my soul, O Lord, for thee, And thy refreshing grace.

A SIMPLE STRUCTURE

The simple structure of the psalms helps transmission too. Unlike some forms of poetry, their shape and rhythm can survive translation. Much is uncertain about the pronunciation and accentuation of ancient Hebrew, but the basic forms of its psalmody were worked out by Bishop Robert Lowth, a professor of poetry, whose Lectures on the Sacred Poetry of the Hebrews was published in English in 1787. He noticed what he called ‘parallelism’. Lines come in pairs, and often the second echoes or expands the first: ‘The Earth is the Lord’s and all that is in it,/ the world, and those who live in it’

(Psalm 24:1 New Revised Standard Version). But the second line may also contrast with or even contradict the first: ‘The Lord watches over the way of the righteous,/ but the way of the wicked will perish’ (Psalm 1:6 NRSV).

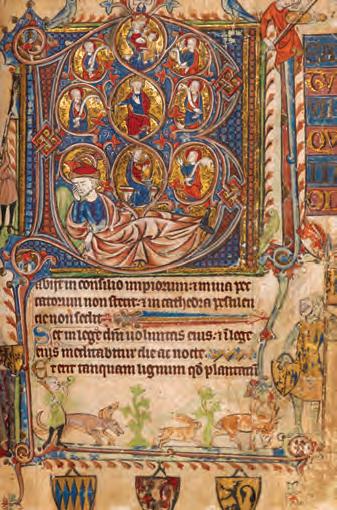

Although that is the basic format, sometimes we come across groups of three lines, or even more elaborate patterns. Other features, including alliteration and occasional rhyme, present baffling problems for would-be translators. A number of psalms are acrostic, with each verse or section beginning with the next letter of the Hebrew alphabet – an effect that Roman Catholic scholar Ronald Knox gallantly

But what about me? I could be humming a chorus I learnt years ago in the Efik language of the Cross River State, southeast Nigeria:

As the ebet is thirsty and longs for the water of life, So my soul thirsts and longs for the Lord.

We are all recalling the first verse of Psalm 42, one of 150 poems composed in ancient Hebrew. The psalms have enriched the praise and prayer of Jews and Christians for more than 2,500 years. What is the secret of their enduring poetic appeal?

UNFORGETTABLE IMAGES

Scholars aren’t sure about the exact species of that thirsty animal. Nystrom simply calls it a ‘deer’. Tate and Brady have imagined a ‘tally ho’ hunt with hounds (‘when heated in the chase’) while my dictionary tells me that an ‘ebet’ is ‘the smallest species of antelope known in Calabar’.

Precise classification doesn’t matter, because everyone can be moved by the plight of this desperate creature, as well as by thoughts of ‘the miry clay’ (Psalm 40:2 King James Version), ‘the rock that is higher than I’ (Psalm 61:2) and ‘a tree planted by streams of water’ (Psalm 1:3). The vivid images presented in the psalms speak movingly across time and space.

Psalm 1 in a 13th-century Latin Psalter

Thinkaloud by John Coutts

tried to reproduce, for example in Psalm 34: ‘At all times I will bless the Lord... Be all my boasting in the Lord... Come, sing the Lord’s praise with me’ (vv1–3).

SO FAR AND YET SO NEAR

Most Christians have favourite psalms, with ‘The Lord is my shepherd’ (Psalm 23) as a probable No 1. But when we read the Psalter right through, we find ourselves in a world very different from ours. Sometimes the psalmists confess their sins, but more often they protest their innocence and call on God to deliver them from their enemies – spiritual, human or both. Not every line is suitable for Christian worship. Many psalms are attributed to King David and some clearly refer to the exile in Babylon, but others cannot be pinned down to time or place. The composer of Psalm 42 has been banished from the Temple and its choir, but we cannot be sure when or why.

At St Trads you might be handed a hymn book and at Trend Contemporary Church asked to gaze at a screen, but in old Jerusalem you would have witnessed repeated animal sacrifice. The world these ancient poets inhabited seems far from ours – and yet still close at hand, for they speak to a living God in words that we can make our own.

When St Columba reached the end of his life on the holy island of Iona, his last action was to copy out the acrostic Psalm 34. Like so many, Columba had discovered, and wanted to pass on, the ABC of good and godly living. When he reached verse 10 – ‘Those who seek the Lord lack no good thing’ – he put down his pen for ever.