7 minute read

to 14

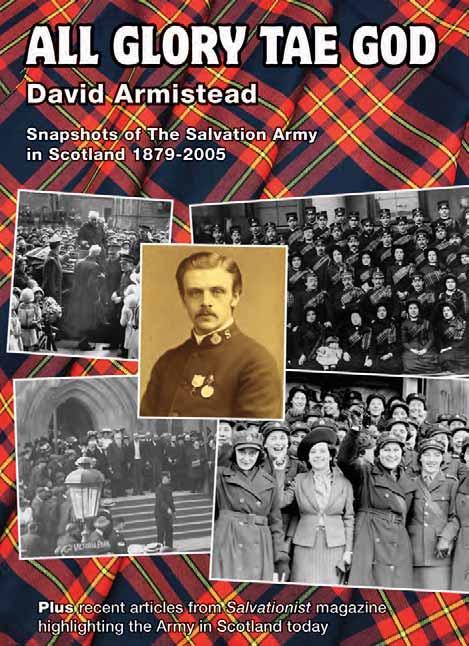

ALL GLORY TAE GOD

On 24 March 1879 The Salvation Army opened fire in Scotland. To mark the 140th anniversary we recall those early days in an abridged account from the book All Glory Tae God by Lieut-Colonel David Armistead

‘F OR a long time we have been looking for an opportunity to open in Scotland. Some years ago we remember being deeply impressed with the need for some such religious effort to reach the unsaved masses of the people, and being also impressed, during a few services we were invited to hold, with the glorious earnestness of the Scotch when their consciences were once awakened by the power of the Holy Ghost.’ With these words William Booth announced to readers of The Salvationist the momentous news that the Army was about to open fire in Scotland.

The year was 1879, a year after The Christian Mission had changed its name to The Salvation Army and the Rev Booth had become known as ‘the General’. Scotland was to be his first opening outside England and Wales, and he was taking care to ensure that it would be a total success.

Glasgow was to be the point of attack – the bridgehead for the invasion of Scotland. A friend of the Army, Thomas Robinson, a Justice of the Peace of Hurlet near Paisley, rented a hall for the Army: the Victoria Music Hall in Argyle Street, Anderston, which could seat more than 2,000 people. It was there that two ‘Hallelujah Lassies’, Sister Eliza Milner and Sister Prentice, opened Scotland’s first corps on Sunday 24 March 1879. In her first report to William Booth, Eliza wrote: ‘Glad to tell you we had a pretty good opening, though not so good as I would have liked, but we had good open-air meetings. Bless God for what he has done already. Fifteen came out to my loving Saviour, and found peace.’ The work took root and grew, despite constant trouble by ‘roughs’ whom the police sought to control. After ten days Eliza wrote: ‘Fourteen souls for Jesus. Collection 8s 2d. Bless God for ever.’ Then the next day: ‘Last night it was a real old hallelujah meeting. Bless God, five souls. Collection 15s… We are so troubled with the roughs. This will be a grand station, I believe.’

The disturbers managed to stop some people from entering the hall the following Sunday but, reporting on the Thursday, Sister Milner was so excited that she forgot to mention the collection: ‘Large congregation, and quite a break down. Twenty-one precious souls – fine big Scotchmen and women – seeking Jesus.’

Sisters Milner and Prentice were soon replaced by Nellie and Suie Cope. A supporter wrote to The Salvationist: ‘I spent the Sabbath with the Misses Cope. I was highly satisfied with the work. The open-air [meeting] and processioning is well attended every night, and twice on Sabbath, all round the streets; the place was crammed full at night, and there was a glorious meeting. I think we have much to thank God for.’

Around six months later, the work spread to Bridgeton in the east of the city, from where two more Hallelujah Lassies, Captain Kate Boyce and Lieutenant Emma Bateson, launched the new work in August or September 1879. The hall, capable of seating 600 people, was immediately filled to overflowing. Policemen were in attendance to maintain order among the crowds seeking entry.

Before long the Army opened fire in the largest fishing port on the eastern side of the country – Aberdeen. Captain Captain Henry Edmonds (front row, centre) with Scotland officers in early 1882

Fanny Smith and Lieutenant Jane Gardiner commenced operations on Sunday 29 February 1880. The next day the captain recounted how the battle had begun: ‘Arrived all right on Saturday at Aberdeen, and had a fire off on Saturday night to a great crowd of people. Good marching yesterday morning, and at night we had the chapel packed to excess, and many could not get in. After the first meeting the people drew out, and the place was soon filled again. There were many convicted, and twelve professed to find peace. I and dear Sister Gardiner are going in for God. We mean Aberdeen for Jesus!’ By the end of 1880 Coatbridge and Kilsyth had opened, bringing the number of corps to five. It was clear that Scotland needed more resources, both human and financial, as well as strategic direction. So, the War Cry of 18 August 1881 announced: ‘Captain Edmonds, ADC, proceeds this day to Glasgow, to take the oversight of the work in Scotland. He is far from well in body, but we look with confidence for reports of a vigorous forward movement down that way.’

This confidence proved well founded, for within a month of his arrival 20-yearold Edmonds reported that three corps had been opened – Partick on 11 September, and Govan and Leith a week later. Three weeks after that he sent in more thrilling news: ‘Gigantic demonstration in Glasgow… Monstre [sic] united meeting yesterday. Ten thousand people on Glasgow Green at 11 o’clock. Streets thronged along the route.’

This huge demonstration – held on Thursday 20 October 1881, a half-yearly fast day in the city – was considered by Edmonds to be an early turning point in the ‘Scotch advance’ of the Army. He told how the soldiers of the various corps met at the Anderston hall and marched to Glasgow Green where a 10,000-strong crowd had gathered. The people were addressed from a lorry platform, the meeting lasting some 90

Captain Kate Shepherd

Major Caroline Reynolds

minutes. A holiness meeting was later held in the hall at Anderston, with 800 people present, followed by an all-night prayer session, during which the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper was administered.

By the end of 1881 five more corps had been established. The first was Aberdeen II, in the Woodside district of the city, which began life on 6 November. The next opening was Glasgow III, at Gorbals, south of the Clyde, which began operations on 13 November. The first officers, Captain Kate Shepherd and Lieutenant Emily Brown, reported that 2,000 people were present on the first Sunday night, ‘of the very class we go in for’, and souls were saved. Barely a fortnight had passed before, on 4 December, the Army arrived in Dundee. Two weeks later another corps was opened in Glasgow (Cowcaddens), while Christmas Day heralded the advent of the Army at Dumfries.

Edmonds ensured that officers always had colleagues nearby to support them as well as to act as reinforcements for new openings. The policy worked well, and with the dawn of 1882, all corps were progressing satisfactorily, both numerically and in terms of the soldiers’ spiritual growth, notwithstanding the frequent mention in their dispatches of flying stones, hard fighting and threats by the police to arrest them should they dare evangelise outdoors.

A notable opening in 1882 was that of the first corps in Edinburgh on 19 August. The Scotsman carried a lengthy report of the event, revealing that the property, a former Presbyterian church, consisted of a small hall, vestry and church officer’s house. Major Caroline Reynolds, who had worked with the Booths from the Christian Mission days,

was the commanding officer and took part in the meeting by singing a solo. A total of 13 corps opened in 1882 in locations including Arbroath, Dundee, Kilmarnock and Banff.

More and more, as the Salvationists became known, local officials such as provosts and bailies came out in their support. Familiarity bred content and consent and, in spite of its members’ eccentricities, the Army was given increased liberty by the authorities to facilitate its labours for the lowest classes. So it was that, when Edmonds presented the colours to Kilmarnock I in June 1883, Bailie Little addressed the assembly, saying that he had missed a number of notorious characters from the police books but had then been pleased to hear that many of them had joined the Army.

Obstructionist officials were becoming