17 minute read

Justice Oliver Holmes,Wendell Jr.

FAMOUS AMERICAN JUDGES

Justice Oliver Holmes,Wendell Jr.

By Harry Munsinger

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on March 8, 1841.1 Using money inherited from her family, Holmes’s mother bought a New England farm near Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Holmes grew to love New England while visiting the family farm. A parochial school for boys and private tutors provided his early education. In 1856, Holmes entered Harvard College2 and studied Latin, Greek, and Rhetoric. Holmes was an excellent student and made friends easily.

The Civil War

The attack on Fort Sumter in April 1860 meant Civil War. Holmes withdrew from Harvard and enlisted as a private in the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia, believing the war would end in a few months. In 1861, war seemed like a grand game for Harvard’s bright young men. Of the 578 Harvard men who served in the Union Army during the Civil War, 36% were killed or seriously wounded. Holmes was injured three times.

Battle of Ball’s Bluff 3

For Holmes and his comrades, the Battle of Ball’s Bluff on the banks of the Potomac River was the first taste of combat. Holmes viewed the battle as a personal triumph because he was brave, although his regiment was badly defeated. Nearly everything went wrong at the Battle at Ball’s Bluff. Holmes was hit in the ribs by a spent bullet and then shot through the chest. Bleeding badly, he was carried down the bluff to a boat and taken to a field hospital. Holmes spent weeks recuperating in Philadelphia before his father moved him to Boston. Holmes rejoined his regiment in March 1862, near Washington, D.C. He felt more afraid in later battles.

Battle at Antietam

Shortly after Holmes rejoined his unit, the unit fought at Antietam, the bloodiest single day in the history of the United States Army. The Army lost more men that day than on the beaches of Normandy on D-Day. Holmes was hit in the neck but managed to walk back to a field hospital for treatment. Surgeons neglected Holmes because they felt he would not survive. He surprised everyone and lived. He returned to his regiment in Fredericksburg, Virginia, but came down with dysentery the day before Union troops attacked the city and were slaughtered by Confederate soldiers. When Holmes returned to his unit, he was wounded by shrapnel in the heel. After that injury, everyone called him Achilles.

Other Military Service

Holmes missed the battle at Gettysburg because of his heel wound, but when he returned to duty, he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and offered command of a Negro regiment. He declined the command, saying he wanted to stay with the Massachusetts militia. In spring 1864, Holmes was assigned to a general’s staff, where he no longer faced enemy fire on the battlefield. He met President Lincoln while serving as a staff officer. Reportedly, he told Lincoln to “get down or you will get your head blown off.” Holmes spent the rest of the war carrying messages. During one ride, he ran into twenty Confederate soldiers, but he galloped through their line on the side of his horse to avoid being shot. Holmes concluded during the war that everything has a price, and it is best to know the cost before undertaking the task.

Holmes the Lawyer and Common Law Scholar

Holmes entered Harvard Law School when the war ended.4 He applied himself diligently because he wanted to succeed and viewed technical expertise as important. After graduating, Holmes went on a grand tour, visiting the House of Commons, viewing the Magna Carta, and touring London art museums. He climbed mountains, stayed with the Duke of Argyll, and went fishing and hunting in Scotland. Holmes was admitted to the bar in March 1867.

After marrying Fanny B. Dixwell in June 1872, Holmes practiced law, edited the American Law Review, lectured on constitutional law at Harvard, and prepared a revised edition of Commentaries on American Law 5 An invitation to deliver twelve public lectures to the Lowell Institute motivated Holmes to write about the common law. Holmes argued that the common law is a summary of procedures and decisions developed by judges to settle disputes rather than a systematic theory of law. He organized the common law according to three principles: first, the common law changes, but conceals that fact by explaining old rules in new ways; second, judges develop policies to resolve real problems in a fair and consistent way; and finally, the common law should be based on objective standards of guilt for equal application by all judges.

Holmes published The Path of the Law6 in the Harvard Law Review, introducing the doctrine of legal realism and arguing that the common law develops through legal decisions made by judges who balance social interests and public policy in deciding cases. Judges soon began using the balancing tests Holmes suggested to decide cases rather than making logical deductions from legal theories. This practice represented a radical departure from the earlier doctrine of legal formalism followed by most American judges.

Judge Holmes

In 1887, Holmes was appointed to the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts.7 There, he heard divorces, torts, and criminal cases; traveled around the state; and presided over disputes involving shady stock transactions, bloody accidents, contract disputes, messy divorces, and terrible crimes, thereby becoming familiar with people he would not have ordinarily encountered. Holmes served as a trial judge for two decades before his appointment to the Supreme Court of the United States.

Justice Holmes

In February 1902, Justice Horace Gray suffered a stroke and resigned from the Supreme Court. President Theodore Roosevelt invited Holmes to his Long Island summer home. Impressed, President Roosevelt appointed Holmes to the Supreme Court on December 4, 1902. Four days later, the Senate confirmed the appointment.8 Holmes was sixty-two when he joined the Court and delighted to be a Justice. When he arrived in Washington, he was met by a gentleman who had been Justice Gray’s messenger and performed personal tasks such as valet, cook, barber, or others. Holmes agreed to hire him.

At the time, the Supreme Court met in the old Senate chambers. Because the Senate chambers contained no offices for the justices, they worked from home. The Court convened at noon and worked until four-thirty each day. The justices met every Saturday in the Court’s library for deliberations. Holmes wrote short, clear judicial opinions, focusing on issues of the case. The other justices characterized his opinions as “clear as a bell.” Colleagues trusted Holmes so much that he sometimes wrote both the majority and dissenting opinions.

His first opinion, Otis v. Parker, 9 upheld a provision of the California Constitution that banned buying stock shares on margin. Holmes concluded that the statute was consistent with the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. During his first term, Holmes wrote twenty-nine opinions, despite starting three months into the term. Holmes said he gave the same consideration to a case involving $25 as to one that concerned a person’s life or the welfare of a state.

Beginning in the late 1880s, the Justices began considering the meaning of due process. They began protecting private property by invalidating congressional statutes that violated the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court held that the Due Process Clause of the Constitution forbids government interference with private property or the functioning of the economy unless the regulation is essential to protect public health. Many of the Court’s decisions indirectly undermined protections offered to newly freed enslaved persons, however. Holmes always believed in judicial restraint, feeling that judges had a duty to examine the practical effects of their rulings and that all judicial decisions ultimately come down to weighing competing interests and deciding between them.

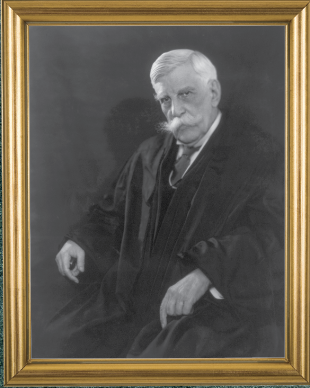

1902 portrait photograph of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Public Domain

Public Domain

Northern Securities v. United States

In 1904, the Supreme Court heard Northern Securities v. United States,10 concerning a J.P. Morgan trust that included two Northern railroads. In a 5-4 decision, the majority held that the trust created a monopoly on railroad traffic across the Northern part of the country, and that the trust must sell the railroads. Holmes dissented, believing the Sherman Antitrust Act was “an imbecile statute.” President Theodore Roosevelt, who had vowed to break up the railroad, oil, and shipping trusts, was not amused by Holmes’s dissent.

Swift & Co. v. United States11

Another antitrust case involved six meatpacking companies that conspired to control the price of beef and pressure railroads to offer low transportation rates. In a unanimous decision, Holmes wrote that Congress has the power to regulate trusts under the Commerce Clause. Holmes expanded the meaning of “interstate commerce” to include any activity that is part of the “stream of commerce” and interstate in character. Following the decision, Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act. Roosevelt was delighted with Holmes after this decision.

In July 1910, Chief Justice Fuller died, triggering a search for his replacement. President Taft appointed Justice Edward Douglas White as Fuller’s replacement. Even though Holmes did not want to be Chief Justice, he felt hurt by not being considered. President Taft appointed six Justices to the Supreme Court during his presidency. The new Justices did not change the basic outlook of the Court and it remained conservative.

Privately, Holmes complained that his new colleagues used repetitious arguments. He resented having to submit his opinions to the criticisms of others, even though he accepted most suggestions to maintain a majority and write the opinion. Holmes worked hard to convince a majority to accept his view of a case by making strategic compromises. He sometimes changed or removed important legal arguments to maintain a majority, but he was never happy to make changes.

Holmes’s Dissents

Holmes enjoyed writing dissents because he could express his ideas without compromise. His dissents became famous during his later years on the Court. He crafted dissents to persuade the next generation of judges that his views of the law were correct. Holmes’s ideas often became the majority opinion decades later. Beginning in 1914, Holmes wrote a series of important dissents that had a lasting influence on constitutional law.

Dissent in Abrams v. United States12

In 1918, the United States conducted a military operation in Russia, even though that country was no longer participating in World War I. Russian immigrants in America called for a general strike at United States munitions plants to protest the American action on Russian soil. The immigrants were charged with espionage because the strike harmed the war effort. Justice John H. Clarke wrote the majority opinion, holding there are limits to free speech during a war, because First Amendment protections are lower when the country is under threat. He reasoned that inspiring unrest and undermining the American war effort contradicted the national interest and could not be permitted during wartime. Holmes and Brandeis dissented, with Holmes arguing that First Amendment rights lie at the foundation of freedom and include the right to dissent even when the country is at war. He argued that the government should not curtail free speech unless there is a present danger of immediate evil or the defendant intends to create such a danger. Holmes felt the actions at issue in Abrams did not create a present danger of immediate evil.

After Warren Harding became President, Taft asked Harding to nominate him Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and Harding obliged. Holmes was skeptical of Taft’s qualifications but came to appreciate the former President’s administrative efficiency and good humor. Taft controlled the Court’s agenda and eliminated repetitive arguments, endearing him to Holmes. Taft cleared the backlog of cases and cut the time needed to obtain a Court hearing to six months. He cancelled the automatic right of appeal to the Supreme Court and gave Justices the authority to decide which cases they should accept.

Holmes’s Health

In 1922, Holmes had his prostate removed. The operation went well, and he was released to recuperate at his farm after a month in the hospital. Holmes decided to install an elevator in his Washington, D.C. home so he could get upstairs to his office and library while recuperating. He moved into a hotel during his home’s renovations. A few months later, Holmes was back working on legal opinions as if nothing had happened.

During Taft’s nine years as Chief Justice, the Court’s majority invalidated nearly one hundred state laws on the grounds that they interfered with private business arrangements, freedom of contract, or a person’s right to private property in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. In many of these cases, Holmes and Brandeis dissented, arguing that if the legislature had a reasonable basis for enacting a law to regulate business, the courts should not interfere. A majority of the nine Justices believed the only justification for regulating a business was health, safety, or public morals. The Court also strengthened defendants’ rights to due process and a fair trial.

Moore v. Dempsey

In the winter of 1922-23, the Court considered an important habeas corpus issue in Moore v. Dempsey 13 In Moore, a group of Black farmers met in a church to oppose extortions by white landlords. Rumors that the farmers were planning an insurrection incited a mob to surround the church and a gun fight broke out. Federal troops suppressed the riot. Local officials arrested the Black farmers and charged twelve farmers with murder. A state jury convicted the farmers after a one-hour trial. The farmers’ court-appointed lawyer called no witnesses and made no challenges to the jury. The state court sentenced the farmers to death, and later dismissed the farmers’ petition for habeas corpus.

Holmes wrote the majority opinion, providing that the verdict was void because no one on the jury could have voted for acquittal and continued to live in the county. He explained that if mob pressure influenced judicial proceedings, and the state judge failed to correct the injustice, the Supreme Court would uphold the defendant’s constitutional rights and order a new trial. Moore was the first time the Supreme Court had intervened in a state court criminal conviction on due process grounds, but it would not be the last. Moore helped secure the right of criminal defendants to due process and a fair trial.

Chief Justice Taft expected Holmes to resign after his prostate surgery, but he recovered and felt competent to continue. There were rumors Holmes would resign on his eighty-fourth birthday, but he continued to work for years after that. He appeared on the cover of Time on his eighty-fifth birthday but refused to give interviews. Holmes said he was happier than he had ever been and was enjoying life.

Nixon v. Herndon

In 1927, Holmes wrote a unanimous opinion in Nixon v. Herndon, 14 ruling that a Texas statute barring Blacks from participating in Democratic primary elections violated the Fourteenth Amendment. He explained that the Fourteenth Amendment was intended to protect Blacks from discrimination and rejected the state’s argument that the statute was political and, therefore, outside the jurisdiction of the Court. Holmes ruled that a state cannot, on the basis of race, deny a citizen the right to vote.

In October 1928, Holmes became the longest serving Supreme Court Justice in history. He continued to deliver his opinions on Tuesday after receiving a case, even though he was getting older and had less energy. Holmes remained sharp and loved being on the Court. In April 1929, his wife Fanny fell and broke her hip. Fanny died nine days later. Taft arranged her funeral because Holmes was so distressed by his loss. Fanny was buried in Arlington Cemetery in a plot next to one reserved for Holmes. Despite his despair, Holmes participated in Court deliberations and wrote dissents.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, 1841-1935. Photo by Harris & Ewing.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540

United States v. Schwimmer

Holmes wrote a strong dissent in an appeal of the denial of citizenship to Rosika Schwimmer, a Jewish Hungarian pacifist who refused to swear she would defend the United States because she did not believe in war. Schwimmer testified that she was willing to be treated as a conscientious objector who refused to take up arms to defend the United States, but that was not sufficient for the Court majority. The majority upheld the denial of United States citizenship. Holmes dissented, writing that freedom of conscience is a fundamental right necessary for a free society and “it is the principle of free thought—not free thought for those who agree with us, but freedom for thought that we hate” which is most important.15 Holmes was not a pacifist, but he believed Schwimmer was “a woman of superior character and intellect” and should receive citizenship despite her refusal to swear she would defend the country in time of war.

In 1930, Taft became too ill to continue working. Holmes, as senior justice, assumed Taft’s duties as Chief Justice until the post was filled. Taft resigned and President Hoover appointed Charles Hughes Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. When Holmes turned ninety, his friends arranged a national radio broadcast that included tributes from Chief Justice Hughes, the American Bar Association, and the dean of Yale Law School. Holmes received hundreds of congratulatory letters. In Summer 1931, Holmes’s health began to decline. Although his mind was still sharp, he lacked the energy needed to keep up with his work on the Court. On January 10, 1932, Brandeis and Hughes visited Holmes and gently asked him to resign. Holmes agreed, delighted that the decision to retire was made for him. In early 1935, Holmes contracted bronchial pneumonia and died on March 6, 1935. After his death, his attorney found two musket balls wrapped in a small paper parcel among Holmes’s personal effects, with the note reading, “These were taken from my body in the Civil War.”

ENDNOTES

1Biography, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. Biography. com, https://www.biography.com/law-figure/oliverwendell-holmes-jr

2Id

3Ball’s Bluff—Harrison’s Island, American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/ battles/balls-bluff.

4Biography, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Biography. com, https://www.biography.com/law-figure/oliverwendell-holmes-jr

5Oliver Wendell Holmes, James Kent, Commentaries on American Law, Franklin Classics, 2018.

6The Path of the Law, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. 1897, https://law.jrank.org/pages/11777/Path-Law. html.

7Oliver Wendell Holmes, History.com, https://www. history.com/topics/us-government/oliver-wendellholmes-jr

8Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., 1902-1932, https:// supremecourthistory.org/associate-justices/oliverwendell-holmes-jr-1902-1932/

9Otis v. Parker, 187 U.S. 606 (1903).

10Northern Securities v. United States, 193 U.S. 197 (1904).

11Swift & Co. v. United States, 196 U.S. 375 (1905).

12Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919).

13Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U.S. 86 (1923).

14Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U.S. 536 (1927).

15United States v. Schwimmer, 279 U.S. 644, 654-55 (1929).

Harry Munsinger is the author of Texas Divorce Guide, The History of Marriage and Divorce, History of Inheritance Law, History of Medical Miracles, and Portraits of Leadership He has served on the San Antonio Bar Association’s publications committee for many years. During that time, he has been a frequent contributor to the San Antonio Lawyer magazine. Although now retired from law practice, Harry continues to contribute to this magazine!