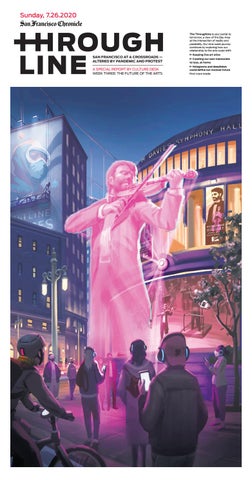

Sunday, 7.26.2020 The Throughline is your portal to tomorrow, a view of the Bay Area at the intersection of reality and possibility. Our nine-week journey continues by exploring how our relationship to the arts could shift:

SAN FRANCISCO AT A CROSSROADS — ALTERED BY PANDEMIC AND PROTEST A SPECIAL REPORT BY CULTURE DESK WEEK THREE: THE FUTURE OF THE ARTS

1 Keeping live art alive 1 Creating our own memorials to loss, at home

1 Holograms and deepfakes could define our musical future Find more inside.

J2 | Sunday, July 26, 2020 | SFChronicle.com

SFChronicle.com | Sunday, July 26, 2020 |

THE FUTURE OF THE ARTS

ONLINE Want to walk into a classic painting? That could become the future of how we interact with visual arts. Read more of these possibilities at sfchronicle.com/throughline.

B U I LT B Y T H E W PA : 5 P U B L I C WO R KS O F L AST I N G B E AU T Y By Peter Hartlaub

I

A B OU T T H I S S ECT I O N

In death, Joaquin Miller never got his wish. ¶ Hoping to go out in an artistic flourish, the pioneer poet had a funeral pyre built at the highest point of his Oakland Hills estate, and demanded that his only service be the lighting of that fire so his ashes could blow with the wind. (Meddling descendants opted for a tasteful public funeral and cremation. Members of the Bohemian Club scattered his ashes from an urn three months later.)

Throughline is a Culture Desk limited-series project exploring what the Bay Area of the near future could look like after the effects of the pandemic and protests take hold. How could we use this moment to reshape our region for the better? On the cover: Check back each week as we reveal another portion of visual development artist Pong Lertsachanant’s rendering of the future of the Bay Area.

PANDEMIC ADJUSTMENTS For a look at how the Bay Area arts and entertainment community is currently pivoting during the coronavirus pandemic, check out Datebook’s Pink section.

STA F F Throughline Editors Sarah Feldberg Robert Morast Designer Alex K. Fong Deputy Photo Director Russell Yip Creative Director Danielle Mollette-Parks Contributing Editor Bernadette Fay Managing Editor, Features Michael Gray Advertising Kathy Castle Account Executive kcastle@sfchronicle.com Follow us Twitter: @SFC_Culture Instagram: @sfchronicle_culture E-mail us culture@sfchronicle.com

John Blanchard / The Chronicle

I N S P I R AT I O N : C R E AT I N G A N E W WAY F O R WA R D

T

his pandemic has forced us to imagine a future without so many things. But it’s hard to envision the Bay Area without the arts. This region, as much as any in the U.S., has infused an appreciation for world-class arts into our DNA — one that won’t end because of a virus. As the Throughline team focused on the arts, we looked into the lessons from Works Progress Administration projects that endure as art. We explored how we can continue to fund art so artists don’t leave our region. And we examined how we can use this moment of loss to create something new and exciting, as art has done through the centuries. Our interactions with art will change. But what won’t is its ability to inspire us, even if we’re creating the art at home, even if we’re experiencing it in ways that once felt like science fiction.

shop online

C E LE B R

ATE MOR E DAYLIG HT WIT

H for your independence

REGAIN YOUR FREEDOM AND LIVE BARRIER-FREE AT HOME

The Bay Area’s BEST Plus Size Boutique

But an even greater artistic statement would arrive more than 25 years later, on the backs of hundreds of Miller’s Bay Area neighbors, and the Works Progress Administration. Laborers hauled hundreds of tons of stone, shale and marble to the estate, donated to the city as Joaquin Miller Park, and built the Cascade — a network of stone walls, waterfalls, fountains and stairways that ascend into the Woodminster Amphitheater. The Cascade is 80 years old and remains squarely in its prime. The Works Progress Administration — a federal agency that built public works projects coming out of the Great Depression — was responsible for thousands of fixes, upgrades and wholesale builds in Bay Area streets, sewers and parks. Walk a couple of miles in San Francisco, and you’ll likely pass a dozen WPA projects big and (mostly) small. But there are several exceptional destinations, where engineering, technology and design combined to create something special and lasting. And they’re more important now than ever — not only as new places to discover during the pandemic, but as a reminder that when the crisis is over, the things we build to be functional will also become works of art. Here are five Bay Area WPA classics, and how they transcend mere function.

Park Street Bridge City: Alameda Construction: 1935 Officials needed a stunt to receive attention when they debuted the Park Street Bridge — one of four bridges over the estuary between Oakland and Alameda, and one of

two rebuilt by the WPA. In a reality show-style flourish, the mayors of both towns married Edith Bird of Alameda and Edward Drotleff of Oakland during a ceremony at the center of the bridge. The drawbridge never needed the publicity. With its steel girders shaped into warm curves, it has become a symbol of pride in the only island city in the Bay Area. And that pride has grown in the last decade. Alameda’s indoor miniature golf course made a hole based on the bridge. The Park Street coffee shop the Local incorporated the bridge into its logo. And shirts with a silhouette of the bridge and the words “The Island” — a play off the Golden State Warriors’ The City logo — are sold in several downtown stores. The Park Street Bridge is a sign of WPA strength, and it became symbolic of a small town’s unity.

Berkeley Rose Garden City: Berkeley Construction: 1933-1937 When Berkeley’s WPA-built rose garden was finished on Sept. 26, 1937, it was as if the community didn’t want it to be discovered. Given the generic let’s-not-makethis-a-destination name, Municipal Rose Garden, the grand opening was announced with one sentence in The Chronicle and no address. More than eight decades later the garden high in the Berkeley hills remains a well-kept secret (I’ll get at least one letter of complaint for giving up the spot) and one of the loveliest and most unusual Bay Area WPA construction efforts. The tiered stone garden is built like an amphitheater on a steep grade, as if the dozens of varieties of roses have gathered for a concert. A redwood pergola, currently being rebuilt, forms a half-halo around the space. Now with the slightly more dynamic name

Carlos Avila Gonzalez / The Chronicle

The Joaquin Miller Park Cascade, built in 1935-1940 by the Works Progress Administration, is a treasure of the era in Oakland and an incredible monument to hard work. Berkeley Rose Garden, it’s a haven for locals, including a robust group of volunteers and visitors of all ages. (We dropped by on a Thursday morning and heard the hide-and-seek words “Ready or not, here I come!” for the first time in a couple of decades.)

Golden Gate Park Fly Casting Pools City: San Francisco Construction: 1938-1939 Golden Gate Park is filled with throwback spaces, but it’s hard to find a place or a pastime as transportive as the Golden Gate Angling and Casting Club. Far off the beaten path — encircled by trees and bushes just west of the Polo Field — the casting pools look like a forgotten swimming hole transported from “The Andy Griffith Show.” But they are in fact world-class pools for fly fishing practice and tournaments, built mostly in 1938 with the support of longtime park superintendent John McLaren, who heard about a WPA fly casting pool in Portland, Ore., and insisted San Francisco create one that was even better. Designed like a golf driving range for fly fishers, the rectangular pools have platforms and places to wade. There’s no more meditative sight in the park than watching casters silently create swirling artwork in the air as they cast their fishing lines. The WPA-built Anglers Lodge is a rustic anchor to the scene, with its stone patio and beautiful woodworking in the main structure.

Aquatic Park City: San Francisco Construction: 1935-1941 Among San Francisco’s WPA projects, Aquatic Park was second in scope and profile only to the San Francisco Zoo. The long-planned bathhouse, park and pier was rescued from construction limbo by the WPA, which provided $1.78 million

to finish the project. Since its 1939 opening, Aquatic Park has served as a casino, military outpost, maritime museum and finally a historic park. But it seems to grow in value each passing year, providing both a functional space and lively throwback to a different time in San Francisco. Through it all the streamline moderne bathhouse remains a classic underrated San Francisco structure, filled with bright sea life murals. The 19th century three-mast sailing ship Balclutha remains docked near the museum, offering a visual counterpoint. And the Municipal Pier, in need of a reinvention, is still an asset for its ghost town vibe.

Joaquin Miller Park Cascade City: Oakland Construction: 1935-1940 Miller donated the land that the Cascade rests on, and more artistic locals became involved with the project, including Tribune Tower architect Edward Foulkes (designer of the Woodminster Amphitheater) and Children’s Fairyland designer William Penn Mott (who designed the park). The stone-and-mortar walls, stairs and giant planters lack firm structure when you’re standing close, looking as if they drifted into the park on a lava flow. But as you climb higher up the stairs and look back toward the three fountains and the beautiful bay views in the distance, the park’s scale is revealed — an incredible monument to hard work. The final climb is a walk past a creek through a woods (it feels like a different microclimate) to the dam-like concrete wall of the Woodminster Amphitheater. We’ll watch plays there again later. But even in the pandemic, there’s still plenty of art left in Joaquin Miller Park.

Peter Hartlaub is The San Francisco Chronicle’s culture critic. Email: phartlaub@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @PeterHartlaub

jest jewels

with Tradition

C e l e b r at e

$15-20

www. jestjewels.com

NEW LOOKS FROM

Alembika Flax Ralston

your independe

Get up to

$300 back on

DaylightMax™ Windows & Doors! BUT ACT FAST» SAVINGS ONLY ON ORDERS PLACED BY JULY 31st

Call Mark Feinman (510) 295-4665

KRISTINE MAYS

for a free estimate on your disability access project Stairlifts Sales • Service • New • Used

SEE THE BAUME ET MERCIER COLLECTION AT

5937 COLLEGE AVE, OAKLAND 510.654.5144

www.alexanderco.com

650-288-0813 Contractor’s Lic. #642553

1.800.simonton · simonton.com

Showroom Open: M-F 8-4

Locally Owned and Operated in Berkeley since 1976 CA License: 659163 Residential Service Sales Support

www.thecompleteaccess.com

“The ancestors and the earth have always been in a dance of abundance that often goes unrecognized.” On display through November 9. Go to www.filoli.org/visit for all visiting guidelines.

1322 Marsten Rd, Burlingame

infullswing.com

Rich Soil

350 Main Main Street, Street, Los Altos • 650-383-5426 smytheandcross.com

86 Cañada Road, Woodside, CA 94062 www.filoli.org | 650-364-8300 | info@filoli.org

$85

1 8 6 9 Un i o n S t r e e t S F 9 4 1 2 3 M o n d ay - S u n d ay 1 1 a m- 6 p m 4 15 - 5 6 3 - 8 8 3 9

j e st j e w el s @ aol . c o m

J3

J4 | Sunday, July 26, 2020 | SFChronicle.com

SFChronicle.com | Sunday, July 26, 2020 |

THE FUTURE OF THE ARTS

MARK THIS MOMENT: I N B R E AT H & TO U C H , 8 WAYS TO OW N LOS S

THE GRAMMAR OF GRIEF IN REAL TIME BY INDIRA ALLEGRA 1 Hold your breath once a day. For as long as you can. Feel your heart thundering. This, too, is a memorial. I feel like (breath is) the theme of 2020 right? It’s either your ability to breathe has been impacted because of a virus, your ability to breathe has been impacted because someone has their knee on your neck, your ability to breathe has been impacted because you’re being tear gassed, your ability to breathe has been impacted because you’re bracing yourself for a loss that you know is coming. 2 When you feel like you need to cry but can’t, pour a pot of tea into the smallest cup you have. Keep pouring. For me that came about because I was literally standing at my kitchen sink and feeling kind of spaced out and tired. … And I continued to pour more tea than that vessel could possibly hold. It’s a really simple idea. Sometimes I have an experience of feeling like I need to cry about something, but not being able to do so for any number of reasons. I feel like other people might be able to relate to that. That was actually more — in the moment — more gratifying than actually drinking the damn thing. You know? Cuz sometimes you just need to make a f—ing mess because it’s a f—ing mess.

By Ryan Kost

3 Make eight hours of your own hold music. Start the playlist with Chuck Berry’s “Worried Life Blues.” Eight hours being a length of a typical workday. Who knows what that even means in the Bay Area, especially if you hold multiple jobs. I have spent so much time on hold for different things during this whole experience. And I think anyone who is also trying to interface — if you’re trying to interface with your doctor, if you’re trying to check on something that should have been shipped to your place five days ago but still hasn’t arrived. If you’re trying to get online with the unemployment people — if you can — to actually speak with someone. I think part of this whole experience of social slowdown around quarantine and shelter in place and whatnot is this feeling of being on hold, not only with your speakerphone going but just in terms of your life in general. Everything is on hold. I feel like that’s the workday right now. And Chuck Berry. … He’s the godfather of rock ’n’ roll.

W

We tend to mark moments with objects. I use the word “moment” very loosely. A moment can be an actual moment — the instant a nuclear bomb explodes and kills tens of thousands, marked later by the Hiroshima Peace Memorial. A moment can be a life marked with a grave or a statue. A moment can be a history of racial terrorism by lynching, marked now by the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala. ¶ Then there is the moment we live in now, a moment defined by a global pandemic and a national reckoning. How can we possibly mark this moment? The writers and editors for Throughline are fine at asking questions, but we leave it to smarter people to answer them. For this question — “How can we possibly mark this moment?” — we turned to Indira Allegra, an Oakland poet and artist who uses pronouns they and them. Their practice, as they put it, “re-imagines what a memorial can feel like, the scale on which it can exist and how it can function through the practices of performance, sculpture and installation.” When we first reached out to Allegra, we told the artist we imagined two monuments. One monument to remember the victims of a novel coronavirus; another monument to remember the Black, brown and indigenous victims of ongoing police violence. We imagined they might conceptualize one of the two. We imagined their idea might take up space in the same way the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., fills up 2 acres. They had something else in mind. Before Allegra began to work with wood and fiber and physical space, they worked with words and ideas and spun them into poems. They describe poetry as a “technology” for exploring memory and trauma and intimacy — “all of those types of human things in a nonlinear way.” Eventually, they say, they got to a place where the poems were asking them “to be more visual,” but for this project, they turned back to words. Rather than a memorial spanning acres, made of concrete and wood and steel, Allegra offers eight prompts — and a potential practice. Rather than separate the lives lost from two concurrent crises, Allegra combines the grief, knowing full well their respective impact on Black people and communities of color. (“With all due respect … the splitting of the two felt really mypoic to me.

It was so flattening. I think the way in which we are experiencing loss — or I am experiencing loss — right now is this very layered thing.”) Rather than offer an imaginary concept for a physical memorial, they offer a very real way to honor this moment. “To be honest I feel like folks who … how do I want to say this? I think that the people we feel most calm around or nourished by, in our lives, are folks who have dealt with the losses in their life and who have a kind of regular hygiene — mental, spiritual, otherwise — around acknowledging loss and, I almost want to say, greeting it on a daily basis. It doesn’t mean that has to be your full-time job. It shouldn’t be a full-time job for anyone. But I do think that courage and care in the face of loss is something which makes an adult an adult.” We tend to mark moments with objects. We can also mark them with actions. What follows are Allegra’s eight prompts, each with a notation drawn from an edited and condensed interview with the artist. These rituals can be performed however and whenever you wish. When our interview had ended, I asked Allegra if there was anything else they might add. They paused for a moment, grew quiet. Then they said this: “When you’re a part of a community or communities that have a history of living with some kind of precarity or vulnerability, losing and the ability to lose almost becomes part of the fabric of your culture. “I feel like one of the things that’s happening right now is that everyone has to be preoccupied with loss.”

Ryan Kost is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: rkost@sfchronicle.com. Twitter: @RyanKost

4 Bake a birthday cake for someone who died this year. Plate two slices. Eat yours. In my home I have an altar to blood and chosen and queer and artistic ancestors. And one of the things which has been important to me is to put something out, to make an offering (on any given ancestor's) birthday. 5 Remember someone’s last words this year. Imagine what their first words might have been. You now have a poem. Recite at dusk. Recite at dawn. The way in which Breonna Taylor will be most widely known is by what happened to her at the end of her life — which is no doubt important and we all need to be grieving and responding to (this). And at the same time she had a whole legacy and I don’t know the details of that, but I know that she had one. We all do. It’s a way of acknowledging the beginning of a story rather than just focusing on the end. 6 Walk through a room. Which objects have you wept in front of? Fill a bag with objects you have not wept in front of. Donate. Recycle. I turned 40 this year. For me part of that has been taking stock of my own life, in a way. Artists don’t have a reputation for living extremely long lives. (They laugh.) So I really have to think about, “Is this the midpoint for me?” And which objects, photographs, music — what has actually helped facilitate some kind of emotional movement for me, some kind of transformation or release for me?

Photos: Yalonda M. James / The Chronicle; icons: Todd Trumbull / The Chronicle

Indira Allegra offers eight prompts to acknowledge change and loss during this time of pandemic and protests, from above: Choose an area of your body that has not been touched by another person in several weeks and allow the temperature of the day to touch it; pour tea into a tiny cup — and keep pouring; bake a cake for someone who has died in the past year, plate two slices and eat your slice.

S H A R E YOU R EXPERIENCES How are you honoring those lost to the coronavirus or police violence? Share your experiences or photos of you following Allegra’s prompts at culture@sfchronicle.com.

7 Consider your legacy. Make a list. You have 8 minutes and 46 seconds. (Editor’s note: 8 minutes, 46 seconds is the amount of time it took the police officer to kill George Floyd by kneeling on his neck.) There are so many time segments that you could … you know what I mean? He had 8 minutes and 46 seconds. I think there’s something about the pandemic plus the gratuitous violence that folks who maybe weren’t paying attention before are paying attention now. 8 Choose an area of your body which has not been felt by another person in several weeks. Find clothing which leaves this area exposed. Stand at an open window for the temperature of the day to touch you. So, I had ovarian surgery in March. Because performance is part of my practice, normally a huge part of my week is going to take class, going to get body work done, going to see an acupuncturist. So in addition to whatever intimate touch might be available to me in my life, there’s this touch I’m also experiencing, just to take care of my body. It was a weird experience for me to be healing from surgery when shelter in place kicked in because friends who would normally come to my house with a meal and be able to offer a hug or physical encouragement … none of that was available. I was like, “How do I heal without the amount of loving touch in my life that I’m accustomed to?” I think we can memorialize the loss of touch in our lives as well.

FUNDING THE ARTS: A RT I STS DREAM UP A C R E AT I V E E COSYST E M By Samantha Nobles-Block

W

Walking the streets of San Francisco’s Mission District, a rich tapestry of public art unfolds, wall after wall embroidered with vibrant murals. Several are by Lucía González Ippolito, an artist, teacher, activist and Mission District native. Her murals — including “Mission Makeover,” documenting the changes in the neighborhood — are regular stops on public art tours, and she co-founded the San Francisco Poster Syndicate, a collaborative that creates and distributes free political posters. “My goal is to use my art to educate people and invoke questions, for those who are being unheard,” she says. Like many other local artists, González Ippolito is navigating the rising boil of the Bay Area’s economic cauldron. Tuition costs forced her to drop out of her art therapy master’s degree program at Notre Dame de Namur University in Belmont, and she stitched together a patchwork of income sources to sustain herself. But the coronavirus has threatened her stability. Her job as a preschool teacher was a pandemic casualty, and she’s living on a grant from the San Francisco Arts Commission, creating a graphic novel about Mission District youth impacted by gentrification, gang violence and immigration issues. She’s not sure what will happen when the funding runs out. Artists like González Ippolito fuel the creative energy woven into the Bay Area’s identity — an energy that informs our sense of place as much as landmarks like the Golden Gate Bridge. But the housing crisis, the disappearance of studios and galleries, and a culture that undervalues their work have made it increasingly difficult for artists to survive here. Like residents of a coral reef, we’ve been living through the slow bleaching of our creative ecosystem. But as the pandemic forces us to rethink how we live and work, and energy from the protests floods our streets, people from all corners of the artistic community are seeing opportunity. They’re moving forward with ideas and projects that have the potential to create a new Bay Area, one where artists and creative workers can survive and thrive. “We’ve been working in a broken system, and COVID-19 brought that into sharper relief,” says Yerba Buena Center for the Arts CEO Deborah Cullinan. “We need support structures for artists and art workers, because we know how disproportionately vulnerable our artists are.” Together with YBCA Chief of Strategy and Revenue Penelope Douglas, Cullinan founded CultureBank, a social investment fund for artists doing community development work. Their first cohort in Dallas created enterprises like a literacy initiative that built reading nooks and distributed free books, and a catering business focused on immigrant women who shared stories through food. In April, CultureBank announced a new Employment continues on J8

J5

J6 | Sunday, July 26, 2020 | SFChronicle.com

SFChronicle.com | Sunday, July 26, 2020 |

THE FUTURE OF THE ARTS

FEASIBILITY RATING Red light: Although some of the proposals are fantastical, even the more practical suggestions are unlikely since the Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture is not planning a reconfiguration.

IGLOOS AND CARS: V I S I O N A RY ST RAT E G I E S FOR LIVE E V E N TS

FUTURE OF MUSIC: IT COULD GET S E R I O U S LY WEIRD By Rose Eveleth

M

Making it in music has never been easy. Successful artists often have to endure long hours, ever-changing trends, corrupt labels, greedy bosses, copycats and constantly shifting business models.

By Sam Whiting

F

For the near term and maybe the long one too, an arts event that involves the gathering of people will likely have to move outdoors, or be staged inside spaces large enough to throw open the doors and let the wind blow through. That means things are going to have to change for most of the performing arts sector. The old standards just won’t work in a world of social distancing and contamination concerns, not even for jazz. ¶ So what will work? And how different will, or should, we experience performing arts? To find out, we empaneled a broad cross section of 22 Bay Area cultural thought leaders and proposed a thought experiment: If you were given a swath of land and allowed to reconfigure aspects of it to create safer arts experiences, what would it look like? To frame the exercise, we asked them to imagine a wide open space like Fort Mason, with a meadow and parking that’s near water. Otherwise, there were no rules, no budgets, no zoning limitations. ¶ And, to clarify, this is purely hypothetical. The Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture is not planning such a reconfiguration. But it is planning to replace an exodus of tenants that includes the San Francisco Art Institute and the arts program of City College of San Francisco. Earlier this month, Friends of the San Francisco Public Library announced that it would not re-open its used bookstore, which has been in Fort Mason for 30 years. Here are some bold ideas for live performances, from floating music to artistic igloos:

popped up, the performers would perform from right there, like a jack-in-the-box. I also love the idea for the repertoire performed to be selected by the audience members from an electronic menu of options, like a juke box in a restaurant.”

Audience ‘igloos’

Oncestree Rocket Ship Treehouse

Dores Andre, principal dancer, San Francisco Ballet

Dana Albany, sculpture and installation artist

Andre imagines a scenario where people get inside clear, mobile, igloo-like constructs that would be located at the entrace of the space. “Each person would get one and walk toward their dot (the dots would be numbered). These dots would be placed on any of the buildings. The ceiling could be raised and open for added air flow, and since the audience would be in pods, we don’t really need to worry about temperature. The dots and pods allow us to have a modular space that can change depending on the needs of the event.”

“As a permanent installation, create a Rocket Ship-Treehouse with nature and technology intertwined. It would become a pillar of hope as it soared 50 feet into the sky, a whimsical, playful creation. The rocket ship would be a collective mosaic of color glass, tile and recycled artifacts ... a time capsule of sorts. Stainless steel tree rises with the spaceship, as limbs and branches embrace one side and branch out to a magical fortress up above. “In the future, the hatch of the spaceship opens as the inside of the spacecraft becomes a unique and innovative classroom, three stories high with a spiral staircase and an observation deck. It is where art meets technology in an artistic playground, think tank and learning facility where teachers, artists, scientists, professionals of all walks of life collaborate, create, learn and educate.”

John Speed Orr, Realtor and retired company member, Smuin Contemporary Ballet

“We propose transforming Lower Fort Mason into a massive hub for the production, display and distribution of public art. Fort Mason would become home base for hundreds of mobile art platforms. These mobile platforms would serve as stages for displaying, experiencing, learning and conversing about art. These battery-powered stages would use cutting-edge autonomous-vehicle technologies to distribute art to the masses in both coordinated and random ways. While these circular platforms would be clustered and maintained at Fort Mason, they would continuously move along city streets and sidewalks, pausing in city parks, public spaces, under the freeways and bridges, along the shoreline.”

“As an artist and a Realtor, housing is near and dear to my heart. So a major portion of the proposal should make the whole of the area focused on creating housing for artists from the Bay Area and residency/visiting artists.” He says this setup “would consist of ‘Live/Work’ artist housing. These particular units could also incorporate a ‘Live/Work’ feel providing for a once-a-month art walk around the perimeter ‘galleries.’ ”

City stage spans the piers Matthew Shilvock, general director, San Francisco Opera

Cadillac Ranch Fort Mason Randall Heath, managing director, San Francisco Dance Film Festival

“Given that this is a moment for tearing down problematic

Performance continues on J9

learning for the whole family. These condensed audiences make their way into the Cowell Theater for a preshow lecture, demonstration and seminar that could draw in subscribers that want more than just a performance.”

Artist housing

Catharine Clark, founding director, Catharine Clark Gallery

Live events continues on J8

The Chronicle photo illustration

Jason Kelly Johnson and Nataly Gattegno, partners, Futureforms design lab

Tear it down and start over

“Use existing structures to create an on-site residency for visiting artists, scholars and creatives. Expand the use of the hostel for a creative laboratory where teams can gather

Proposals for remaking outdoor performance spaces include one-way walking lanes, socially distanced circles, a drive-in theater and an outdoor stage.

Art Swarm City

“I propose the development of this new open space as a center for live dance, theater, music and screenings. The space would be organized around the model of a drive-in theater where individuals can park and remain safely sequestered in their cars while viewing a large central stage, supplemented by an Oracle Park-style HD video board for optimum viewing. “And in a nod to the San Francisco roots of one of the enduring American public art installations, Cadillac Ranch, I propose the space feature a series of fantastical art cars, each designed and fabricated by invited artists and laid out in a semicircle grid facing the main stage. Similar to a circus carousel, each car would have a unique identity. Patrons would have the option of either driving their own cars to the events, or for those without vehicles, booking their favorite car in advance. Additionally, boats, kayaks and other craft could be docked along the piers to experience the shows remotely.”

Now, the novel coronavirus has shuttered concert venues across the country, with no real end in sight. Indoor concerts will likely be the last thing to reopen — small spaces, sweaty bodies and lots of shared air make for perfect viral swapping conditions — and many artists predict that the impact on the music industry will linger long after the virus is gone. “The venues aren’t going to make it, and we can’t go back to where we were before if all the venues and theaters are closed,” said Rachel Lark, a San Francisco musician. Art often thrives when presented with restrictions, and boy does it have them now. Artists are faced with a unique set of challenges, and the way they adapt could bend the arc of music history in surprising directions. In the early days of the pandemic, many musicians turned to online events — Zoom concerts and Instagram Live sets hastily set up in living rooms and kitchens. But the artists I spoke with found these kinds of performances unsatisfying (no matter what Erykah Badu says). “My performance style really needs to be experienced in person,” said Lark, who offers Zoom concerts but is trying to figure out other ways of performing that feel more intimate to her. Frank Okay, a Chicago artist, agrees that these online sets leave a lot to be desired. “I’ve played a couple, and I’m sure that a handful of people tuned in, turned it off mute for a minute, and then put it back on mute and left it open so they could still be a good friend.” Perhaps you’ve had a similar experience, tapped into your favorite band’s stream to find that there’s just something missing (do you clap for an artist who can’t see you, alone in your living room?). Both Lark and Okay said that instead of trying to exactly mimic the experience of a concert — the press of bodies, the thump of the speakers, the smells, the energy — the better thing to do might be to try and figure out which pieces of live events you can re-create. Lark is experimenting with a drive-in-movie style show, where the audience would attend in separate cars and watch her perform on a stage. She also considered some kind of walk-through performance (think haunted hayride but instead of jump scares, musical acts) or a pre-recorded concert that worked like a walking tour. Okay, on the other hand, is looking for even more of an escape from reality. The musician, who uses nonbinary pronouns, created a new “fake” band called Uh, Pocalypse and started releasing music as these new characters who live in a world without the same structural inequalities we do. “Fixing the world’s problems

Jason Kelly Johnson

A rendering of Art Swarm City by Jason Kelly Johnson and Nataly Gattegno that would create a public art display that could become a creative hub.

and racist monuments, renaming sites and otherwise reconsidering what it means to memorialize places, people and events connected with a history of violence and oppression, I think Fort Mason should be razed, preferably by relatives of the Ohlone peoples, but possibly also by artists of Mexican descent.”

PA N E L O F A RTS L E A D E RS

Blow up Pier 1 for open-air stage

Dana Albany, Dores Andre, Nataly Gattegno, Frish Brandt, Catharine Clark, Phillippa Cole, Khori Dastoor, Amos Goldbaum, Randall Heath, Jason Kelly Johnson, Gordon Knox, Lyz Luke, Pam Mackinnon, Angela McConnell, Davia Nelson, Kevin Nelson, Terez Dean Orr, John Speed Orr, Matthew Shilvock, Heather Snider, Meredith Tromble and Lynne Winslow.

Terez Dean Orr, company member, Smuin Contemporary Ballet “Let’s hypothesize that we take away Pier 1, building out an open-air stage that overlooks the Golden Gate Bridge and Sausalito. Leaving the parking lot empty and creating a deck that connects to Pier 2, patrons can pack a picnic, bring a chair and a wool blanket to keep them warm on those foggy evenings. Sunset performance anyone? “Guests, perhaps 50 or so at a time, can choose to start their evening at Pier 2 or Pier 3. This is where we will host other artists’ work, pop-up restaurants and interactive

“A massive stage would be erected over the top of the three Fort Mason piers — a huge elevated canvas upon which multimedia theatrical events could take place. Huge, architectural scenery (think Bregenz Festival) would be a backdrop to stories told about our city, with the city itself as a backdrop. The stage would be a beacon of artistic hope and promise — a gathering place on a mega scale. “What better way to social distance an audience than to put them on boats! People would rent them or use their own and head out into the Bay, and surround Fort Mason on all sides. For those whose sea legs are a little shaky, social-distanced viewing would also be available on the Great Meadow. “A 360-degree experience in which you can take in the city, the (Golden Gate) Bridge, Alcatraz, and extraordinary art, all in one moment. Told on such a vast scale that social distancing becomes imperceptible. We are all still together as a community. This is our city’s stage.”

Juke Box Orchestra Phillippa Cole, director of artistic planning, San Francisco Symphony “I love the idea of the Symphony orchestra literally popping out of a shipping container on a flatbed truck and performing on the back of that truck, which could drive to various locations ... where people would be walking around or sitting in socially distanced circles. The Orchestra members could be sitting in place so that when the floor of the container

Socially distanced sculpture garden Heather Snider, former executive director, SF Camerawork “Paint 6-foot circles across the entire parking lot and grounds. Then convert the parking lot to a sculpture garden with plenty of room to wander about while keeping a social distance. The wall between the parking lot and the fields above has a natural amphitheater shape making it a perfect place to carve out a terraced stage for bands, theater and live performance, which could be enjoyed by socially distanced spectators in the 6-foot circles.”

Open the existing rail tunnel through Upper Fort Mason and add a ferry terminal Kevin Nelson, interim managing director, Magic Theatre “Convert the piers into indoor/outdoor performance/event spaces with retractable or tented roofs to allow for airflow and increased social distancing flexibility. Add smaller performance/art spaces throughout Upper Fort Mason, including an outdoor amphitheater in the Great Meadow. “Connect upper and lower parks with an escalator or open-air funicular. Extend Muni lines through the tunnel to Fisherman’s Wharf and extend the trolley line. Put in a Fort Mason ferry terminal. Put patio spaces on the waterfront and on the rooftops of the landmark buildings for dining and socializing.”

Culture Lab Fort Mason Angela McConnell, executive director, Montalvo Center for the Arts

J7

J8 | Sunday, July 26, 2020 | SFChronicle.com

SFChronicle.com | Sunday, July 26, 2020 |

THE FUTURE OF THE ARTS

BURNING MAN: CAN IT REIGNITE PUBLIC ART?

Live events from page J7 for sustained periods to develop and produce new works and test new ideas. Landscape designers will transform the parks and grounds to provide pathways and resting areas to support the needs of social distancing and accessibility. “Throughout the public park visitors will find installations, live creative engagements, local sustainable edible gardens and orchards. They can join small classes or check out VR headsets, sealed after each cleansing, to experience performance and projects from an expansive archive of works. “Piers 2 and 3 will become retractable and flexible performance and presentation spaces that could accommodate thousands in wide open performance venues, or retract to create intimate pods for small familial groups to experience live performance and presentation. “Automobile viewing and participation portals will be created throughout the parking lots for those who would prefer to remain in the safety of their own personal space.”

By Gregory Thomas

The future of art galas Lynne Winslow, event producer, Winslow & Associates “To put on an event, we create multiple pods or bubbles for small groups of 6-10 people within the pier. These could be as elaborate as Plexiglass domes or as simple as 10-by-10-foot tents with clear walls. Lounge furniture or other easily sterilized seating in unique designs are within each bubble. There will be catering alleys behind the pods and waiters will pass the food and drinks through windows to guests in each space. “Performances can be projected onto the interior roof with guests reclining in socially distanced beds or hammocks to view. For dinner dancing, we’d have Bumper Bubbles — inflatable spheres that guests wear or step into, creating a barrier of safety while having a ball. “For an art fair, the gallery could be set up in the form of a maze with the audience moving in one direction, discovering artwork every 12 feet. Audio cues prompt the guests to move to the next piece and therefore maintain a safe distance and flow among guests.”

SPACE (Sierra Pacific Art Center at Fort Mason) Meredith Tromble, professor interdisciplinary studies/art & technology, San Francisco Art Institute. “SPACE reconceives Fort Mason with an emphasis on culture production and virtual distribution, limiting on-site presentation to small groups. SPACE invents art and audience structures to nourish art in the Sierra Pacifi c bioregion while amplifying the positive environmental changes initiated by the pandemic shutdown. “Parking lots are replaced by landscaping with one-way footpaths, plantings that defi ne small-group gathering spaces while providing food for birds and insects, and several small-scale outdoor performance areas for music and dance. “One-way circulation paths are designated in existing buildings and for existing paths in the Upper Fort to minimize face-to-face contact (while) walking,

Employment from page J5

group of six West Oakland artists working on projects to spark community change. CultureBank is also exploring collaborations with art collectors to leverage their collections’ value to fund forgivable loans for artists, and partnering with health organizations to pay artists based on improved health outcomes from their work. “We’re disconnecting art from the financial system that ignores the value our artistic communities bring,” Cullinan says. “It’s not a return on investment, it’s a ripple on investment.” Meklit Hadero, YBCA chief of program and a talented Ethiopian jazz singer and songwriter, sees potential for those ripples to become a tidal wave. “We’re at a place where we can reshape our systems. I have a lot of hope for this moment,” she says. “But equity can’t be an afterthought. It needs to be baked into our recovery, as does creativity, at the ground level.” The pandemic has also accelerated the ongoing loss of galleries, vital ven-

Amos Goldbaum

Dores Andre

S.F. muralist Amos Goldbaum’s line drawing shows how Fort Mason would open like a tackle box. Above, from left: S.F. Ballet dancer Dores Andre imagines spectators in individual igloos and safely spaced in the performance space; a rendering of artist Dana Albany’s Oncestree Rocket Ship Treehouse.

ues where artists show and sell their work. Those that remain are often perceived as walled gardens, barring artists and audiences from entry. Gallery owner, artist and curator Rhiannon Evans MacFadyen wants to change that. Her gallery, Black & White Projects, is temporarily closed due to the coronavirus, but Evans MacFadyen is collaborating with a group of artists on an arts-based social club model that would use tax-exempt 501(c)7 or 501(c)8 legal structures typically used by organizations like the Elks Lodge and the Bohemian Club. The social club (dubbed the Society of the Smokey Mirror) is still in the experimental stages, but when indoor spaces are permitted to reopen, Evans MacFadyen sees potential for a self-sustaining, inclusive artistic space where artists could show their work and manage their own sales transactions without paying gallery commissions. After seeing the loss of artistic spaces throughout our region, San Francisco Ballet principal dancer Mathilde Froustey founded La Maison, a performance space, gallery and

running or biking. “Outdoor digital screens wrap around the walls of the Lower Fort parking lot. Programming for these screens is shared with a circuit of neighborhood and regional art centers so that no one has to use fossil fuel to experience it.”

Petlenuc Amphitheatre, Ohlone for ‘The People’s Stage’ Lyz Luke, associate director, Living Jazz “Until we have a vaccinated public, outdoor concerts are the way of the future. Luckily for Fort Mason, there’s a ton of outdoor space which lends a huge advantage over most areas barring outdoor stadiums. The venue would need to book some fairly large names with artists that attract a culturally and ethnically diverse crowd. This is an opportunity for Fort Ma-

artist residency, in 2017. The physical location has permanently closed (another casualty of the pandemic), but Froustey is working on a virtual La Maison with partners from the art and technology worlds. She envisions a membership-based model that would create a digital venue for dancers to interact directly with their audiences and funnel revenues back to participating artists. “We need to be able to make a living and still dance,” she says. “We’re all struggling.” “We’re in the middle of this accelerated change. We need new prototypes and new ideas,” says JooWan Kim, founder and artistic director of hip-hop orchestra Ensemble Mik Nawooj. He sees tech money as one path to a sustainable creative ecosystem in the Bay Area. “We need to have companies like Facebook and Amazon fund new concepts and ideas in the art world,” he says. “We should have a universal basic income for artists if they’re doing work that benefits the Bay Area.” But Kim also sounds a cautionary note about this potential evolution, one

Dana Albany

Dores Andre

son to reopen as a hub for culturally diverse events and crowds.”

Reimagined Fort Mason Amos Goldbaum, mural artist “ ‘Reimagined Fort Mason’ works the way a tackle box opens up to turn an interior space into an exterior. It is a completely silly and impractical idea — how will people get up there? Where are the bathrooms? While encouraging outdoor activities vs. indoor ones is great, congregating in large groups is not. The real solution is much more mundane but unfortunately even more unlikely: Pay people to stay home until it is safe.”

Sam Whiting is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: swhiting@sfchronicle.com. Twitter:@samwhitingsf

that applies to many sectors of the art world. “We need to have a system of rotating gatekeepers,” he says. “Everyone has biases, and we need to make sure that artists aren’t kept out because of it.” Others see potential in our streets, as the pandemic forces us to rethink traditional arts spaces. “On every city block in San Francisco, we should create at least one open space that can be used by the community for creativity,” says Dena Beard, director of the San Francisco experimental arts space the Lab. “Doing something like that would be messy and complicated, but it’s the kind of messy and complicated we need. The arts are a means of changing perspective. Artists show us a different way of seeing the world.” What world would we see if these visions became reality? Imagine it: Traditional institutions turn inside out, and art moves from behind walls and out of silos onto the streets. Those streets and sidewalks are permanently repurposed for both transportation and celebration — art, sculpture, dance

and performance open to all. Galleries, theaters and virtual venues evolve to give artists new ways to connect with audiences while making a living, and the legacy gatekeepers that decided who was seen (and paid) lose power. Deep financial support from sectors like health care, business and technology offer artists the time and space to make ambitious work outside the “commercially viable” box, and many focus on benefiting their communities, creating deep-rooted change. Through it all, audiences are immersed in new perspectives, broadening their perception of what is possible. An explosion of that magnitude could reshape everything. Hadero says, “From art, we create culture. From culture, we build policies. From policies, we build cities.” Perhaps the opportunity to build the city, society and world that we want is here — and artists can lead the way, inviting us to soar. Samantha Nobles-Block is a writer based in the Bay Area. Email: culture@sfchronicle.com.

W

Gabrielle Lurie / The Chronicle

When the group behind Burning Man called off the desert gathering amid the coronavirus pandemic in April, it dashed the hopes of thousands of Bay Area burners who build their lives around the annual event, including Kate Greenberg. “Like everyone, I went through a period of mourning for the experience I thought was on the horizon,” she said. Unlike other burners, Greenberg, a 31-year-old architect in San Francisco, had been tapped to design the pavilion at the center of Black Rock City upon which the eponymous wooden Man stands — that is, until the climactic moment when the massive effigy is set aflame. It’s an honor among the builders, designers and engineers whose wild creations are a primary attraction for event-goers. The base, the largest standing structure at the event apart from the temple, functions as a central lookout platform with panoramic views of the surrounding city. Greenberg’s vision, to fit with the event’s Multiverse theme, was an interactive framework of large wooden domes — “bubble universes,” she calls them — around a centerpiece lined with mirrors. “My approach was to see if I could take the place where people go to look out and see if I could get the individual to look inward and find themselves at the center of the event,” Greenberg said. “It was intended to become an empowering moment that nodded back to the idea that, at the end, Burning Man is to each person what they make of it.” But in April, instead of gearing up for her fifth burn, Greenberg found herself, like just about everyone in the Bay Area, stuck at home on lockdown, cut off from her community. “I was at my lowest that second week, when this was really becoming a reality, and it was so uncertain and scary,” she said. Since then she’s been sketching new ideas for future Burning Man projects, working from home and hosting impromptu dance parties with friends via Zoom. “It’s not that the uncertainty has gone away, but I think we’ve begun to find space within it.” Rather than scrap the event entirely, Burning Man organizers are cobbling together a digital facsimile of the gathering, which will be hosted online the first week of September. The details of how it will work are vague, but organizers hope the virtual version is more expansive and inclusive than a weeklong party in the harsh Nevada desert for which entry costs upwards of $600 and tickets sell out online almost instantaneously.

Performance from page J7

is not something I know how to do. But I like to imagine the world without its problems,” Okay said. And making music for these fictional people, in a world where they’ll never have to perform that work in a live venue, has been freeing. “I don’t have to worry about what it would be like to play the show, or whether people are going to think the lyrics are silly.” Their next online show will project images and other experimental layers on top of the live video, to see if adding

Architect Kate Greenberg was tapped to design the pavilion at the center of Black Rock City at this year’s Burning Man, which was canceled because of the coronavirus. She stands with her piece “Opus,” created for a previous Burning Man, at her workspace on Treasure Island.

“When we talk about the future of art, we should be talking about the equity of art and how we give people the opportunity to share their voices and share their experiences.” KATE GREENBERG

elements can make the show more evocative. These kinds of experiments aren’t new (think: The Gorillaz or Janelle Monae’s concept albums or the Whitney Houston hologram tour) but they might become more common, and our willingness to entertain them might increase, too. Where reviewers and fans once cringed at Houston’s hologram, or rolled their eyes at music videos presented in augmented reality, without “real” shows to attend, they might give a bit more leeway in these unprecedented times. Travis

“Burning Man has this way in which, if you’re not habituated or connected in the travel-to-the-desert version of it, you don’t really have access to it,” said Kim Cook, Burning Man director of art and civic engagement. The virtual event, she said, will showcase a new generation of digital creatives pushing the boundaries of traditional art. It’s a moment for Burning Man to reach outside the playa. More broadly, it’s a chance to consider whether the burner community’s guiding principles — radical inclusion, communal effort and civic engagement, among them — can inform our newly energized efforts to rethink public institutions and societal values during the Black Lives Matter movement and coronavirus pandemic. Greenberg’s focus is creating meaningful, shared experiences through public art. In a series of phone calls, she spoke about how opening opportunities for artists may help foster more equitable and inclusive communities in the Bay Area. Q: If there’s a silver lining to this period, it’s that we are re-evaluating all kinds of institutions and behaviors and societal values. Do you think that could extend to the art industry? A: When we talk about the future of art, we should be talking about the equity of art and how we give people the opportunity to share their voices and share their experiences. I don’t think it’s ever been done well or equally. There’s a real disparity in the diversity of the opportunity within the arts for minority artists when you look at traditional venues and the audience they’re trying to reach. That’s one thing that’s very special about Burning Man. We often think of museums as the places where art becomes art and is acknowledged, but Burning Man offers new artists a voice. It provides support for pieces but also validation for someone to recognize themselves as an artist. Q: A lot of us are only moving around in our small neighborhoods right now. What can we take from the experience at Burning Man that could help us engage with our neighborhoods? A: That’s hard. People at Burning Man are incredibly invested and engaged with their community because it’s one that you choose, that you help to create. There’s also this surprise and delight that comes out of Burning Man and casually encountering extraordinary things on a daily basis there. I think there’s a way where we can create surprise and delight in our outdoor environment for people to discover. You see some of that every year in the Parking Day, where people take over parklets and turn them into something new for 24 hours. But there are a lot of small spaces in the city — medians, alleys, blank walls.

Scott recently performed in the video game Fortnite as a larger than life version of himself, to a reported crowd of 12 million people. If there must be a screen or a piece of technology between the audience and the musician because being together isn’t safe, more artists might fully commit to the new possibilities afforded by a digital experience. If Celine Dion can duet with her own hologram in Vegas, what else could be possible? “This is an opportunity to challenge what it is to perform music live at its

It’d be interesting to look at the opportunities around us right now: What are void spaces that we can transform? Q: How can we use art to foster that kind of enthusiasm? A: Art can be a way to communicate with your community. It might be the extent of walking around and feeling safe in asking, “Can I do something here? Can I express myself? How can I change what I’m seeing in my neighborhood? How can I augment it, make it more beautiful and talk about what I’m feeling?” I’m not sure there are simple answers to those questions, but I think they come when people have a sense of ownership of their space. Q: What do you think about this year’s virtual Burning Man event? A: I don’t believe that the virtual event will ever be a true substitution for the real thing — not at this point in time. But what an interesting opportunity, right? For the first time you can bring art that could never physically be there (in Black Rock City) because you don’t need to worry about the 50-80 mph winds and the dust. There are all these challenges to building out there that don’t exist in the virtual realm, and this is a chance to showcase new art. I’m not that (digital) artist, but there are plenty of creatives out there that could really make something special from this opportunity. Q: Do you think we might come out of this with a new path for public art and how it’s created or presented? A: There’s certainly a pretty captive audience if people want to make art right now. I walk to Golden Gate Park and the area around the Panhandle, and I’ve seen some spontaneous concerts given from doorsteps, which is really exciting. If we’re shutting down an entire street, for instance, could that street be given over to sidewalk art? We’re seeing these feelings spilling onto our doorsteps and sidewalks. Maybe we could organize those ideas a bit more — start connecting the dots between those opportunities and presentations. Q: How do you think this moment will translate artistically? A: I’m anticipating that the artistic statements that come after this time are going to be something very unique because it’s really one of the first times that, globally, we’ve all had this shared experience of uncertainty and trauma. Our individual experiences are all different, but it’s a shared experience nonetheless, and I think that’s pretty unusual. Art that comes out of it could resonate very widely.

Gregory Thomas is The Chronicle’s editor of lifestyle and outdoors. Email: gthomas@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @GregRThomas

most fundamental level,” said Okay. “This is an awesome opportunity, and a really challenging opportunity.” It’s not hard to imagine a future where techsavvy artists start to leverage the power of additional technology like deepfakes, CGI and animation to build entire worlds around concept albums, performed exclusively in Minecraft or Animal Crossing or some other digital space. Imagine a personalized concert where an artist records live renditions of all their songs and you can choose your set. Or

an augmented reality experience where you encounter different musical acts while walking around your community, like Pokemon Go but for musicians. Imagine being able to karaoke with a deepfake version of your favorite artist, or watch them puppeteer a whole army of characters they dreamed up to tell a story. The possibilities are immense, and often very weird. Rose Eveleth is a Bay Area writer and creator of the Flash Forward Presents podcast network.

J9

J10 | Sunday, July 26, 2020 | SFChronicle.com

T H E F U T U R E O F T H E A R TS

A BIT OF FICTION: ‘ T H E G R E AT AWA K E N I N G ’ By Molly Liu

H

Her car windows slowly roll down, inviting a wisp of chilly, crisp air that is all too familiar to Mei, though nothing within her line of sight evokes any sense of familiarity. But she is no longer an outsider in Hayes Valley — no sense of the piercing neglect that bleeds into her most recent memory of the city. The San Francisco she had left was a dead one. Mei passes the SFJazz Center and turns left, gradually easing to a stop. A large sign blocking traffic reads “Permanently closed for pedestrians CREATIVES.” Her lips curl into a slight smile. So it’s happening? Her eyes then wander to the new murals, the paint beautifully blended in with the colors of flickering lights that line the streets. Mmmm, the smell of fresh paint — strong and seductive ... nostalgic. A past that has long gone. She draws a deep breath, taking in the chemical aroma. But now revived in 2022? To her left is a vacant yoga studio, barely noticeable behind thick wood panels that signified its closure. A middle-aged woman in front swipes her brush over the wood with exaggerated movements, forming wide, abstract strokes. Across from her, a young violinist’s bow dances to Brahm’s concerto. A crowd of appreciators sways to its tunes. Mei opens the car door and swoops her daughter up, shifting her stacks of canvases in the back. Lina lets her hand slide into her mother’s and, habitually, rubs on Mei’s hardened calluses. As they walk, her eyes fixate on a thin, off-white building in the middle of Ivy Street. Memories flash back. Mei remembers. She was on her knees, screaming, crying, begging — one hand over her pregnant belly. She had been dragged out of the flat after her landlord filed a lawsuit against her. A battle she lost. Rent prices had surged astronomically in the past three decades. Most of her friends, artists as well, had left the Bay. But she refused. San Francisco was her home — where her grandparents settled in the early 1900s. It was where she started her work as a painter, capturing the hidden life of ’90s Hayes Valley, when the central freeway still towered above. Back in the days when poets and revolutionaries lined the cafes, joined by artists, hippies and queers openly flaunting their personalities. San Francisco was the dream for any young, bohemian frolicker. She persisted through the internet age, the dot-com burst, the mass influx of young workers to the Silicon Valley dream. Through Facebook and Google, and then the other unicorns. She watched her city succumb to the demand for tech and talent. She watched her friends flee one by one. She protested the gentrification of Hayes Valley, the lack of affordable housing, the forever increasing rent. Until she couldn’t any longer. Mei never really understood whose fault it was. At first her anger was channeled toward the newcomers, then the city for allowing them in, and then the companies that built this empire. Resentment turned into grief, and then to acceptance. Nine years had passed since Mei had stepped foot inside the city. But now she was back. And the flat, the one she was so forcefully and unjustly evicted from, is now back in her possession. She looks down at Lina, at her innocence. Mei knows she will never truly understand the beauty nor the

The Chronicle photo illustration

Nine years had passed since Mei had stepped foot inside the city. But now she was back. And the flat, the one she was so forcefully and unjustly evicted from, is now back in her possession. She looks down at Lina, at her innocence. Mei knows she will never truly understand the beauty nor the ugliness of the past. It’s for the best.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR Molly Liu is a Bay Area writer and essayist. Read more of her work at www. siyumollyliu.com.

ugliness of the past. It’s for the best.

* **

“Mama, is that your old house?” Lina asks, following her mother’s gaze. She picks up a large piece of stained glass from the sidewalk and peeks through the yellow filter. A laugh bursts from behind, and a tall, bearded man with frazzled gray hair appears. “Please — let the child play.” His voice is friendly. “Mei, wow, you’re here. What has it been? Ten years?” “Nine, actually. But yes, a long time. Good to see you again, Gary,” Mei scans his figure. “Wow, you look thinner ... and older.” Gary smiles, “All the days stressing through the pandemic, that’s all.” “Are they really all gone?” “Almost. Still a few lingering up by the Marina but they’ll probably be gone by the end of month. The others are huddled in Pac Heights and the Presidio. At least the Mission and Castro are clean.” “Who’s gone?” Lina asks, curiosity lurking. Gary’s face lights up with delight, “Well look at you! All grown up. The last time I saw you was when you were still inside your mama!” He kneels to match Lina’s height. “You see, this place here wasn’t like this before. That music that you hear, the murals on the walls — that’s all new. It used to be full of young rich folks working computer jobs. They took over this area and kicked your poor mama and me out.” “Well not intentionally. We just couldn’t coexist,” Mei corrects Gary. “Yeah sorry, I don’t give them any of my pity. They’re all just selfish dudes who convince themselves they’re doing good for the world. See? After the rona they just moved out! To Bali, or Denver, or wherever there are beaches and mountains. Taking advantage of every crisis.” Mei sighs. Gary has been critical of the tech community for as long as she’s known him. He was a poet with a stained glass side hustle that didn’t mesh well with the yuppies, and he took it as a personal offense, lashing out his anger by blaming the tech industry for destroying the culture of the city. What Gary wanted, a resurgence of the San Francisco renaissance, was simply not going to happen. But finally, things took a turn in 2020. Following the pandemic, the homeless population surged when more evictions poisoned the city. With a majority of Silicon Valley companies shifting to remote work, the city saw a large exodus of tech workers to safer, family-friendly towns. Housing prices dropped, offices relocated. Landlords had a moment of scare and started frantically selling their buildings, an act colloquially coined the “tech flight.” At first it looked as if San Francisco couldn’t be saved, but then came the artist coalition, composed mostly of displaced artists from the Bay, who fought a yearlong battle with the city government. They petitioned the mayor and ultimately gained support and state resources to turn many of the heavily discounted buildings into artist co-ops and community shelters for the homeless. There were conditions, of course. It was then when Mei phoned Gary, reconnecting with her old friend. Gary had scoffed at the idea of moving back. In his jaded view it would take a miracle for something substantial to change. “But look,” Mei had persisted,

“there’s already so many people moving back — like, musicians, painters, poets like yourself! They’re looking for people to head these co-ops. This IS a miracle.” Gary was stubborn, but he ultimately caved. They joined the coalition and opted to lead the co-ops in Hayes Valley, which included Mei’s previous flat. Wounded by the past and apprehensive of the future, they endured many sleepless nights in the weeks leading up to the move. Lina’s tug snaps Mei back to the present. “I want to see more!” Lina demands. “Mei, I’ll take her around. You start getting settled in,” Gary offers. Gary takes Lina by the hand and walks her to what was once Patricia’s Green. The grassy area has been transformed into a flourishing, sustainable garden with tomatoes dangling from vines, chiles and herbs of all kinds, and various lettuces sprouting from the soil. In the corner, a young fig tree towers over a rosemary bush. The scent of lavender from the garden greets the aroma of freshly baked bread from a cafe. “We’re turning this center block into a garden so we can cook for the community.” Gary points to an unfinished bamboo structure to the left of the garden. “There, we’re building an outdoor kitchen.” He turns around to a row of fancy apartments. “And those will be artist studios. Each artist gets their own space —” “Where are they taking them?” Lina’s eyes widen at a media artist weaving wires into his work. A man in a suit next to him packs a few of his artworks into a box. “Oh that, yes, so we sell our work to the city and state government to pay for the housing. I believe it’ll be another 20, 30 years before we completely own everything. Not a perfect model, but it helps us build this,” he says as he flails his arms around to signify the vast expanse of a self-sustaining artist co-op. “Was it like this before they came?” Lina asks as two sculptors walk past, carrying a marble carving of deadbeat robotic caricatures. “They? The computer people? Ah, yes. I mean no, it wasn’t like this before. This ... is new. The old model, it didn’t work because we all had to leave. We developed this new system so they can’t come back again and, you know, destroy its soul again.” He bit his lip. “Well,” Lina starts cautiously, “they’re gone, right? Is the soul also gone forever?” Gary is fond of the little girl. “Yes, they’re gone for now. Don’t worry, the soul is still here, we just have to look deep.” She doesn’t understand. If anything, this neighborhood has more soul than anyplace she’s seen before. Lina takes a large brush from a can of red paint. She gets on all fours, and uses the brush to outline a shape around her. “Then I’m giving it a heart,” she beams.

* **

Mei watches the two of them from her balcony above. The neighborhood is a canvas, a diary, a garden, a music studio — anything the artist wants it to be. This is what Lina will grow up to know of her city. It isn’t perfect. But it comes pretty darn close. The San Francisco she knows now is alive.