8 minute read

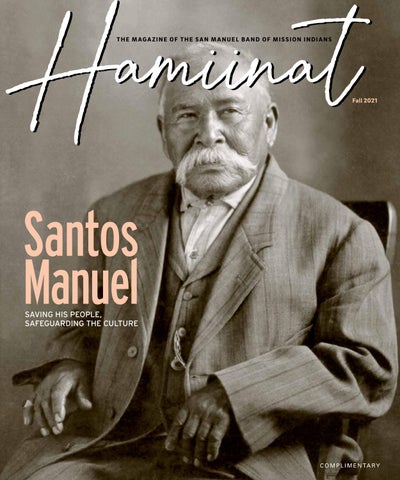

Santos Manuel

KIIKA’ OF THE YUHAAVIATAM CLAN OF SERRANO INDIANS

The leader, healer and friend who saved the people and safeguarded their culture for generations to come.

By Clifford E. Trafzer

At the beginning of time, the Creator gave the land, water, plants and animals to the Yuhaaviatam, or Pine Tree people of Southern California. The domain was vast and included the San Bernardino Mountains, lands north and east of the mountains in the Mojave Desert, much of the San Bernardino Valley and the northeastern portion of the San Gabriel Mountains.

This place on earth was more than property: It was the only place that the Creator had designated for the Yuhaaviatam; and the people had obligations of stewardship and reciprocity to all things in their homelands. The Creator taught the first people how to live with each other and with the plants and animals.

———

As a young boy, Santos Manuel was taught by his elders how to live in harmony with the environment and follow the Creator’s laws. He learned the sacred songs and stories of his people, and where those stories are embodied across Serrano territory.

He was born in 1814 into the village of his father in the San Bernardino Mountains and named Paakuma’ by his parents. Since the Spanish had given his father the surname Santos, some people called Paakuma’ by the name Manuel Santos or more commonly, Santos Manuel. The Spanish also named the people Serrano, indicating they were from the mountains or highlands.

Santos Manuel distinguished himself as caring, thoughtful and intelligent when he was still a child. Elders saw him as a future leader, so they expected much of him. His parents and other elders among Yuhaaviatam people treated him with respect but demanded more from him as a way of preparing him for leadership.

About the age of 12, Santos Manuel and other boys experienced their puberty rites ceremony. Elder men met with initiates to prepare them for a future life of service. At that moment, they had no idea about the enormous challenges Santos would have to navigate for the survival of his people.

———

Even as a young man, it was clear Santos Manuel would lead his people: he was the recipient of a song that described the huge landscape the Creator had given his people, the Maara’yam – of which his clan, the Yuhaaviatam, are a part. This song served as an oral deed to the land and resources, which Santos Manuel held for his people and passed on to his son, Tom Manuel.

During the middle of the 19th century, Santos Manuel became the Kiika’ of Yuhaaviatam people, and one of the great Native leaders of Southern California. In addition to his natural talents as a leader and healer, the Creator gave Santos Manuel a strong body and keen mind, all of which he used generously to help others.

The Big House

A.K. Smiley Public Library, Gerald Smith Collection

He was an exceptional deer hunter and, following the traditions of his people, Santos Manuel made his first deer kill at a young age and gave away the venison. As the leader of the Yuhaaviatam, he had the responsibility of caring for and sharing with all his people.

George Murillo, the husband of Santos Manuel’s great-granddaughter, Pauline Murillo, explained, “He always made sure his people had food.”

Native Americans far and wide understood that Santos Manuel controlled all the resources within the Yuhaaviatam landscape. If others wished to hunt or gather on this landscape, they had to ask permission.

Jesusa Manuel with Richard Manuel in a basket

A.K. Smiley Public Library, Gerald Smith Collection

But he always shared the natural bounty, including many acres of black oak, live oak and piñon trees, which provided acorns and pine nuts. As long as his people had food, Santos Manuel graciously gifted the Gabrieleno (Tongva), Kitanemuk, Kawaiisu, Chemehuevi, Cahuilla, Luiseño, Mojave and others with foods from Serrano lands.

———

The Yuhaaviatam lands and resources were a perpetual gift from their Creator, but in the 18th century, the Spanish claimed to have discovered these lands and later, in the 19th century, Mexican and American governments claimed them as their own.

For over 100 years, settlers moved onto Yuhaaviatam lands, built homes, removed trees for logging, mined for precious stones, polluted water and allowed livestock to decimate the natural world. All of these incursions destroyed the Serrano way of life and their subsistence- and trade-based economy.

By the 1860s, California settlers had enslaved American Indian men, women and children and, in 1866, the pivotal moment in Serrano history occurred: the murder of two Native boys by a group of settlers, leading to an unprovoked war against not only the Yuhaaviatam, but all Native people from the San Bernardino Mountains to the Colorado River.

The 32-day massacre, conducted in the face of great danger…he by a settler militia supported by the California governor, resulted in an untold number of deaths. It was a gruesome and inhumane act. By one account, a volunteer soldier bragged about killing two Indians with one bullet. He shot a young woman in the back as she ran away, the bullet passing through her body, killing her and her baby.

The Serrano knew how to fight enemies, but Santos Manuel counseled his people not to fight the settlers. Instead, in order to save the remnant of his people, which numbered less than 30 at this time - Santos Manuel gathered his people and moved them out of their mountain home to the San Bernardino Valley.

“Santos Manuel took action,” said tribal Chairman Ken Ramirez, a great-great grandson of Santos Manuel. “He acted quickly and saved many lives.”

Santos Manuel

A.K. Smiley Public Library, Gerald Smith Collection

His descendants often remark about how Santos Manuel knew intuitively when settlers planned to harm his people. At those times, tribal elder Pauline Murillo said the leader would advise tribal citizens to stay out of town. Santos Manuel would also take villagers into the mountains to hunt and gather natural items for tools, baskets, houses and weapons, thereby avoiding settler violence.

Chairman Ramirez said, “Santos Manuel saw things before they happened and acted to protect his people, his tribal family.”

———

The San Manuel Reservation, established by a Presidential proclamation in 1891, had a commanding view of the San Bernardino Valley where residents could watch for approaching visitors. Tribal elder Dolores Crispin told her family, “Look now you see that I am telling you this, so you can pass it on to your children. Hear me well, see that faint little speck of light way down there from the homes of whites. Someday, there will be more and more.”

After being chased out of the mountains by a murderous militia, Santos Manuel and his remaining band lived a refugee existence for three decades along the banks of Warm Creek. The leader then established a permanent village in the foothills above present-day Highland, where the Tribe has lived since the late 19th century. California Assembly Member and tribal citizen James Ramos remarked, “Santos Manuel provided the will of survival in the face of great danger…he taught the people resilience.”

Jesusa Manuel at Oak Glen

A.K. Smiley Public Library, Gerald Smith Collection

In addition to his skill as a leader, Santos Manuel had a powerful connection with the spiritual world, which informed his relationship with his homelands, his people and his neighbors. He was a holy man, and a remarkable healer who called on the spiritual world to heal the sick. Even after he passed, he appeared in spirit to heal his granddaughter, Martha Manuel.

Santos Manuel oversaw ceremonies in the Big House or Kiič Atiü’ac on the reservation. He was strong as a bear and when he blessed and cleansed the Big House, he crouched like the fierce animal as he prayed and sang. Some say it made the earth shake.

But even with this strength, Santos Manuel expressed peace and friendship to settlers as well as his loyalty to the United States. In fact, every Fourth of July, he dressed in clothing made from an American flag and traveled by train, shaking hands with passengers.

“In my home, we have the picture of Santos Manuel dressed in the American flag with his top hat. He showed kindness and reached out to others, as we still do today,” Chairman Ramirez explained. “The San Manuel Tribe is very much part of our Inland area. We are deeply and proudly patriotic because we are loyal and dedicated stewards of this land – our home. Like Santos Manuel, we bridge our Native American world with other residents of our homelands.”

———

Santos Manuel died in October 1919. He lived through Spanish missionization, the MexicanAmerican War, the California Gold Rush and the Civil War, as well as the American settlement of Southern California, the coming of the citrus industry, urban development and World War I.

In spite of all this upheaval, change, uncertainty and pain, he maintained his culture and responsibilities, passing on his leadership traits to his people. Today, tribal leaders honor him and follow in his footsteps.

Assembly Member James Ramos, who is also the great-great grandson of Santos Manuel, said, “People in California, and around the country, should know what happened to Serrano people and other California Indians. They should know the truth about the fighting, killing and genocide. The Yuhaaviatam population was down to thirty people at one time. Our people were nearly exterminated…without Santos Manuel we might be extinct today.”

Chairman Ramirez shared that Santos Manuel and other tribal elders urged the people to always remember who they were and where they came from. The elders wanted them to remember their ancestral land had been gifted from the Creator and to hold onto their traditions, their way of life.

“Our elders saved our culture and language, bridging the old ways with new ways. Santos Manuel refused to carry the bitterness of the past but created a new path for the sake of seven generations to come,” Chairman Ramirez explained. “He taught his people the traditional values that live within every tribal member today. This is the spirit of Santos Manuel and we want our children to know this spirit. That is why we pay homage to Santos Manuel.”

© Edith Johnson, Brenda Romero and Gail Schwartz. UCLA, Ethnomusicology Archive