Journal of the Santa Barbara Historical Museum

The Play’s the Thing

The Play’s the Thing

Santa Barbara’s Cultural Renaissance

Santa Barbara’s Cultural Renaissance

by Hattie Beresford

No.

Vol. LVII

1

2

Although Santa Barbara has fostered the arts since its inception, in the years following the Great War (World War I), the arts flourished in new and exciting ways thanks to the creation of the Community Arts Association. Historian Hattie Beresford reveals the rich history behind the genesis of this organization, whose purview came to embrace a host of Muses.

A child of the Progressive Era, the Community Arts Association sought to enrich the lives of all Santa Barbarans by enlisting them in the creation of the arts, whether that be painting, singing, acting or playing a musical instrument. Architecture and landscape design also came into play. Consequently, the organization came to have three branches, Drama and Music, Plans and Planting, plus the School of the Arts. It also promoted and became part owner of a community theater, the Lobero.

The Community Arts Association (CAA) only lasted 20 years, but they were exciting years of cultural growth and emersion for Santa Barbara. Though no longer with us, the Association left a long-lasting legacy and inspired future generations and organizations to continue its quest. Today’s CAMA (Community Arts Music Association) is a direct descendent of the CAA and recently celebrated its 100th anniversary.

The local renaissance began in 1919 with the establishment of the Community Chorus and the aptly-named La Primavera Organization. Both inspired the development of the Community Arts Association and its Players. Beresford has chronicled their formative years and the incredible dramatic and artistic talent that was drawn to Santa Barbara by this original branch of the organization. Many who trod the boards or worked behind the scenes went on to life-long careers on stage, movies, and television.

AUTHOR/EDITOR: For the past 18 years, Hattie Beresford has written a local history column for the Montecito Journal called “The Way It Was,” in which she has been able to indulge her long-standing interest in the people and events of Santa Barbara’s past. She is also a regular contributor to the Montecito Journal Magazine. In addition, together with the Santa Barbara Historical Museum, she co-edited and produced the memoir of local artist Elizabeth Eaton Burton entitled My Santa Barbara Scrap Book and wrote two Noticias, “El Mirasol: from Swan to Albatross and “Santa Barbara Grocers.” In 2018, she completed the 100-year history of the Community Arts Music Association entitled Celebrating CAMA’s Centennial. That same year, she published her own book, The Way It Was ~ Santa Barbara Comes of Age, which is a small collection of her over 400 articles.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: The author is thankful for the contributions of retired Director of Research Michael Redmon, Archivist Chris Ervin, the University of Rochester in New York, and Cranbrook Institute of Design in Michigan.

FRONT COVER IMAGE: Detail from photo of “La Primavera” dancers is courtesy of the University of Rochester, New York, who gave the author permission to use photos from the Arthur Farwell Collection, part of Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections at the Sibley Music Library of the Eastman School of Music.

BACK COVER IMAGE: Eleven of the terpsichorean Months pose on the hillside behind the stage. The local girls who played the roles were as follows: Esther Janssen, Irma Carteri, Melanie Brundage, Eileen Foxen Stewart, Emma Orella, Francis Harrison, Frances Ellsworth, Nellie Riedel, Helen Harmer, Ethel Harmer, Eleanor Beverly, and Annie Aquistapace. Mary Schauer played Primavera.

Kathleen Baushke, Designer

©2022 Santa Barbara Historical Museum

136 East De la Guerra Street

Santa Barbara, CA. 93101

sbhistorical.org

ISSN 0581-5916

NOTICIAS

The Play’s the Thing Santa Barbara’s Cultural Renaissance

by Hattie Beresford

1 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

No.

Vol. LVII

1

In 1887, the young people of the town borrowed costumes from a traveling troupe performing Gilbert and Sullivan’s Mikado, and held a Mikado party at the Arlington Hotel (site of today’s Arlington Theatre). Among the group were the future stars of the Amateur Club performances. Back row, third from left, stands Nathalie Anderson Sawyer, whose amateur acting career would last through the 1920s when she performed with the Community Arts Players. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

NOTICIAS 2

uSanta Barbara’s Cultural Renaissance The Making of the Community Arts Association

In 1918, Johnny came marching home from the muddy trenches of Europe only to find a plague had infested the town of Santa Barbara. Erroneously dubbed the Spanish Flu, the global pandemic had taken over the stage in October and didn’t make its final bow until February 1919.1 Though fatigued by war and pestilence, the town had learned to work together during these difficult times, and the time was ripe for a new stage to be set, one on which the creation of a great cultural institution known as the Community Arts Association would come to tread the boards. For the next ten years Santa Barbarans would see and participate in an exciting artistic renaissance as well as a blossoming of civic and commercial enterprise. The cultural renaissance, however, did not spring fully formed from the heavens. Rather, it developed over time and reached back to roots established centuries ago. Art, Music, Drama, and Song had been part of Santa Barbara’s indigenous Chumash culture and all those who came after. For the Chumash, in-

struments were constructed from natural sources. Cocoon rattles, for instance, were made by filling the cocoon of the ceanothus silk moth with pebbles, and flutes and whistles were made of deer and bird bone. Clapper sticks of elderberry provided percussion.2

After the establishment of the missions, which began in 1786 in Santa Barbara, Christianized (neophyte) Chumash peoples were instructed in the singing and playing of sacred music, and the Spanish settlers brought regional folk music and art from Spain. Music became a key factor in developing relationships between the Chumash and the European colonists, in fact, it became a common language.3

After 1850, an increasing number of Americans came to settle in the old adobe town of the new state of the Union, and the variety of music increased as well. “Oh My Darling, Clementine” vied with “Viva la Ronda,” and John Philip Sousa, Gilbert and Sullivan, and Shubert, Strauss, and Bach took to the stage.

3 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

3

There was no actual stage in town until Giuseppe Lobero completed construction of an adobe theater in Chinatown on East De la Guerra Street. He named it the Opera House, and it became Santa Barbara’s first community theater. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

There was no actual stage, however, until an Italian named Giuseppe Lobero arrived in 1859. He was a musician and an opera singer, and the Spanish community adopted him and dubbed him José. In 1873, Lobero completed construction of an adobe theater, and he scheduled an opening that featured a chorus, soloists, and an orchestra made up of local talent that he had trained. Lobero’s Opera House became Santa Barbara’s first community theater, and many different civic events, entertainments, and amateur performances were held there over the years, as well as additional performances by repertory troupes and other traveling professional entertainers.4

The American residents brought with them a desire for East Coast cul-

ture. In 1875, the first dramatic performance at Lobero’s theatre was staged by the Denin-Sawtelle Troupe, which presented a series of plays typical of the times including Rosedale and Rip Van Winkle. 5 In 1888, the young people of the town formed the Amateur Club and produced and starred in a series of plays starting with Sardou’s A Scrap of Paper. This play inaugurated the new Santa Rosa Hall, which had a stage and auditorium and stood on the corner of Anacapa and Arrellaga streets.6

Instrumental music is also woven through the fabric of Santa Barbara’s history. At the approach of the 20th century, the orchestra students of Professor William J. McCoy formed the Amateur Musical Club and took rooms in a building on Anapamu Street.7 In 1905,

the music teachers in town formed the Music Study Club to study and promote high quality music. To raise funds, they brought world-class performers to the Potter Theatre, including the Russian pianist Ossip Gabrielowitsch (1909), who delicately rippled through a program of Schumann, Chopin, and Paganini, and the incomparable red-headed Polish heartthrob, Ignace Paderewski (1908), who would set aside his piano to serve Poland during World War I as a diplomat and in 1919 as prime minister.8

As for the visual arts, Santa Barbara’s natural beauties and evocative Spanish

culture drew so many renowned artists that by 1908, magazines and newspapers were talking about the Santa Barbara Artists’ Colony.9

Organizations that involved local residents in vocal music included the 1876 Philharmonic Society, which performed on Lobero’s stage and at fraternal halls and churches in town.10 Other early choral organizations were the Orpheus Club and the church choirs. In 1916, Principal C.A. Hollingshead of the high school organized a community chorus, which met at the new Recreation Center.11 It alternated concerts and often joined the Municipal

5 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

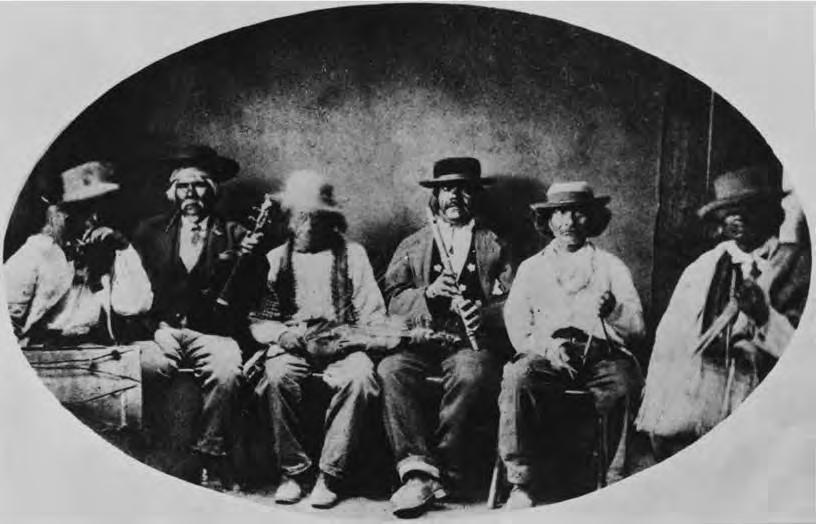

In 1873, Christianized Chumash musicians hold instruments in the arcade of Mission San Buenaventura. The Spanish missionaries instructed neophyte Chumash people in the singing and playing of sacred music. (Wikimedia Commons)

Sardou’s A Scrap of Paper inaugurated the new Santa Rosa Hall with its intimate stage and seating for 400 people. It was the first production put on by the Amateur Club, a theatre company made up of local residents. (From scrapbook belonging to Elizabeth Eaton Burton; courtesy of Jean Hunt)

Professor William McCoy’s students formed the Amateur Musical Club in 1892. McCoy’s orchestra had accompanied the plays put on the by the theatrical Amateur Club, and the local orchestra gave Sunday concerts at Plaza del Mar and elsewhere. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

Depicted here by Lawrence Alma-Tadema in 1890, Ignace Jan Paderewski was an enormously popular and well-known Polish pianist whose wild mane of red hair made women swoon. In 1913, he bought Rancho San Ignacio in Paso Robles and planted zinfandel grapes, thereby inspiring the area’s Paderewski Festival, which pairs music with wine. During World War I, he returned to Poland to serve as Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs, before returning to the concert stage and performing again in Santa Barbara. (WikiMedia Commons)

NOTICIAS 6

Orchestra, which had been formed the same year by a joint venture of the Santa Barbara Chamber of Commerce and the Commercial Club.12

The community chorus idea, which had captured the imagination of the nation in the 1910s, had been born of the idealism of the Progressive Era. It strove to bring about music that would bind people of all classes together with unified purpose and spirit. According to Thomas Stoner in his article, “The New Gospel of Music,” Arthur Farwell was probably the greatest visionary advocating a new era in which cultivated American music would be produced for all people. 13

Farwell was a composer, conductor and ethnomusicologist, and in 1913 he had teamed up with Harry Barnhart, a charismatic choral director in New York. Out of this partnership, the principles of the community chorus movement were born. The two men believed that the primary goal of such a chorus was for the emotional, intellectual, and spiritual unification of a community, and that the artistic quality of such a chorus was of lesser importance. All people, not just those schooled in music, could sing and experience the transcendent power of communal singing.14

On April 2, 1917, the United States joined the European War, and troop trains stopped at the Santa Barbara depot to ferry boys and men to training camps and transport overseas. Principal Hollingshead organized the local chorus to sing patriotic songs and ordered songbooks. It was everyone’s patriotic duty, he said, to join in and make these

The year 1891 marked the formation of the St. Cecilia Club, a charitable organization that raised funds for hospital expenses. Initially, they planned to give a series of concerts to raise needed funds for medical expenses, and their first foray was a cantata inspired by Alfred Lord Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott.” Elizabeth Eaton Burton, first president of the organization, arranged to have the score sent to Santa Barbara from London for the February 2, 1892 performance. (From scrapbook belonging to Elizabeth Eaton Burton; courtesy of Jean Hunt)

“Sings” a success.15 By 1918, the song books had been scrubbed of all tunes of German origin and replaced with patriotic songs that aimed to “stimulate and advance the new virile American spirit” created by America’s part in the world war.16

7 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

Above: Arthur Farwell (top left) and Harry Barnhart (seated right) with other members of the Commission on Training Camp Activities of the War Department during a National Conference on Community Music at the Hotel Astor in New York in 1917. Farwell would establish a Community Chorus in Santa Barbara in 1919. (Library of Congress)

Right: Initiated by State and Local Councils of Defense, Community “Sings” increased in popularity during World War I. The 1918 Liberty Edition songbook erased all songs of German origin and replaced them with patriotic airs that were to “stimulate and advance the new virile American spirit created by our part in the war.” (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

NOTICIAS 8

u Inspiration from July 4, 1919

With the war and the pandemic firmly in the past, plans for Independence Day 1919 would start the ball rolling for the cultural renaissance of the 1920s. When a group of the city’s businessmen joined members of pioneer American and Spanish families to form a committee to plan a celebration of America’s participation in the Allied victory and to honor the sacrifices made by American soldiers and civilians during WWI, they decided to go BIG. Five days of activities were to celebrate U.S. military forces, Santa Barbara’s Spanish heritage, Santa Barbara’s history, and the returning American soldiers as well as veterans of all previous wars.17

One of the prominent long time Santa Barbarans who created the festivities was the artist, Alexander Harmer, whose brush had been preserving the stories and life style of the original Spanish settlers since 1896. Arts and Crafts artisan and landscape architect Charles Frederick Eaton was another. Eaton had been instrumental in establishing the annual but short-lived floral festivals in the 1890s.

Also participating was Francisca de la Guerra Dibblee, granddaughter of the former comandante of the presidio

and wife of Thomas B. Dibblee, an early rancher in Santa Barbara. Another was Katherine (Catarina) Den Bell, a descendent of the Ortega family and keeper of the history of those early Santa Barbara days through newspaper articles and, later, through her book Swinging the Censor. Her input was essential to the plans. The list of other pioneer residents who participated in creating the grand fiesta was long.18

Edwin H. Sawyer, once proprietor of Montecito’s Hot Springs resort, expressed the importance of the festivity when he told a Morning Press reporter, “We owe the past a big debt of gratitude, and our Spanish heritage is one

Catarina Den Bell, a descendent of the Ortega family was one of many pioneers consulted in plans for the Spanish festivities in 1919. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

9 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

The five-day celebration of America’s Independence in 1919 opened with a historic Spanish parade, program and festival. Note the great variety of activities ranging from diving girls at the pleasure pier to a tennis tournament on the grounds of the Belvedere (former Potter) Hotel. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

that must not be permitted to fade into forgetfulness . . . . The past is sacred. If we can make Santa Barbara the rallying place for descendents of the pioneers and reverence for the memories through song, story, and pageants, we will be engaged in a truly worthy work. . . . Our younger generation needs to be reminded of what has come before.”19

Plans for the July celebration, therefore, included building casitas and ramadas along today’s Cabrillo Boule-

vard, and inviting descendents of all the old Spanish families in the surrounding area to participate in a Spanish parade that featured beautiful antique clothing, caballeros on silver studded saddles and flower-bedecked floats. Other activities included Spanish games, and, of course, music and dancing.

On July 2, the newspaper reported, “It was Spanish day and gay splotches of color, prancing horses mounted by dashing dons, strains of lively music of

11

BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

SANTA

This photo from the July 1919 Spanish Parade was used five years later to promote the inaugural “Old Spanish Days” fiesta. In 1919, the parade and festivities took place at Plaza del Mar and on today’s West Cabrillo Boulevard. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

Old Spain, and graceful dancing to the echo of castanets presented a picture to thrill the hearts of both old-timers and newcomers.”20

The following day the historic pageant commenced with the ahistorical landing of Sebastián Vizcaíno, who had named the Santa Barbara Channel in 1602, but never stepped ashore. The parade continued through the days of the Chumash, the missionaries, and then vaqueros and rancheros. Then came the American pioneers with stagecoaches and flower floats followed by the United States Navy and other local military organizations and city officials. The Fourth of July itself was given over to patriotic addresses and a parade of veterans.21

It had been a grand celebration, one that people talked about for days. On July 6 the Morning Press headline blared, “Plan to Make La Fiesta Annual Affair.”

In September, those plans came to fruition. At a meeting of prominent men of the city, the decision was made to once again attempt to create an annual pageant. While past attempts had included floral parades aimed at the promotion of Santa Barbara’s horticultural riches, this one was to commemorate the early history and romance of Santa Barbara. Because it was to be held in the spring, they decided to call it La Primavera.

For the Independence Day celebrations of 1919, only the character of explorer Sebastián Vizcaíno landed at Leadbetter Beach, but when Fiesta was initiated in 1924, Cabrillo joined him. In actuality, neither man ever set foot on the Santa Barbara mainland. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

“We want to give a higher grade pageant than anything before attempted in the state, and we believe it would attract thousands of visitors,” said the Chamber of Commerce representative. “It would become to Santa Barbara what the Portola celebration is to San Francisco, the Carnival of Roses is to Pasadena, and Mardi Gras is to New Orleans.”22

The group promoting the idea was heavily populated by the city’s varied business leaders. Real estate developers, attorneys, civic promoters, grocers,

Inspired by the success of the parades of the Independence Day celebrations of 1919, a group of Santa Barbara businessmen and civic promoters incorporated as La Primavera Association. They garnered financial guarantors and laid plans for an annual spring pageant celebrating Santa Barbara’s Spanish heritage and history. Their logo shows the sun gracing the cornerstone of that history, the Santa Barbara Mission. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

13 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

and even the sheriff were advocating for the festival. On October 30, 1919, they incorporated as La Primavera Association. James B. Rickard became president, Clinton B. Hale, Arturo G. Oreña, and Hobart C. Chatfield-Taylor became vice presidents.

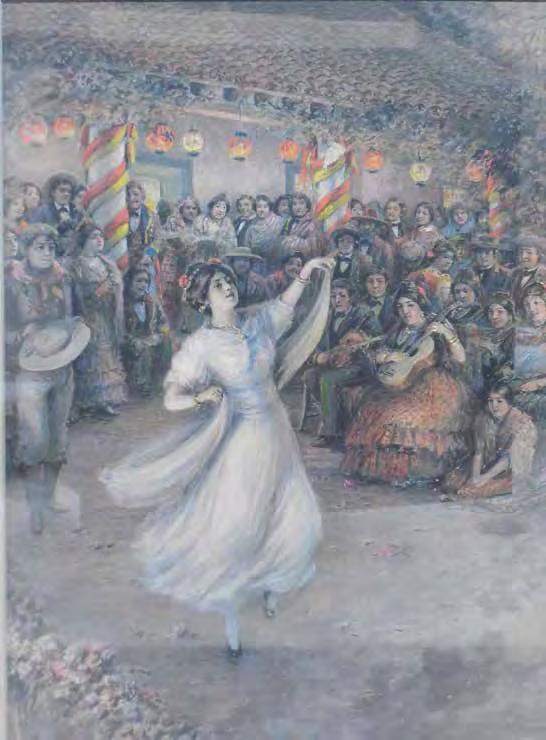

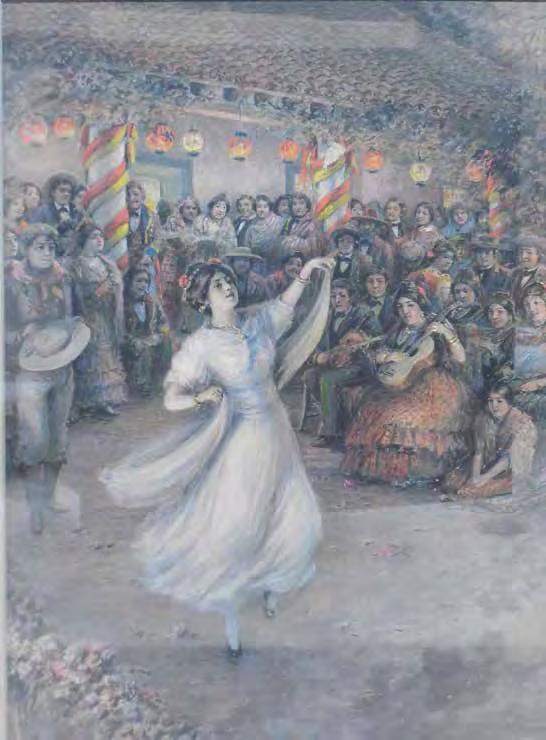

Artist Alexander Harmer’s life’s work became painting the stories and lifestyle of the old Spanish families, as this scene of a fiesta at Casa de la Guerra illustrates. His expertise, and that of his wife, Felicidad Abadie, contributed greatly to the 1919 plans for La Fiesta. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

NOTICIAS 14

u A Community Chorus Comes to SB

Between 1910 and 1920, the population of Santa Barbara nearly doubled to 20,000 residents. Among that increase was a large cadre of talented, cultured Easterners who had succumbed to the beauty of Santa Barbara’s landscape, its salubrious climate and the charm of its romantic Spanish past. After World War I ended and the Spanish Flu departed, many Santa Barbarans felt the time had come to rebuild cherished institutions as well as the economy. Increasingly, it was the influence of these newcomers who were to usher in a Golden Age of Culture in Santa Barbara.

Four days after the meeting to establish La Primavera, the Morning Press announced that community chorus founder, Arthur Farwell, was coming to speak at the Recreation Center. He had been invited by a group of civic-minded citizens, led by playwright, poet, and suffragist Marion Craig Wentworth, to create a community chorus.23 Inevitably, the two efforts, La Primavera Association, which hoped to increase the coffers of Santa Barbara businesses, and the Community Chorus, which hoped

to increase communal spirit and culture through local participation in the arts, would join together.

At the meeting at the Recreation Center, Farwell said that song was the origin and foundation of all other music. “Through the community chorus, many pageants, entertainments and patriotic gatherings can be arranged to furnish Santa Barbara with the best of musical numbers and instill in the people a love of art, such as no other method can do,” he said.24

The University of California at Berkeley had hired Farwell to direct

Marion Craig Wentworth, poet, suffragist, and playwright invited Arthur Farwell to come to Santa Barbara to establish a Community Chorus. She would later teach drama at the Santa Barbara School of the Arts. (Carolyn and Edwin Gledhill portrait; Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

15 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

Arthur Farwell in 1921. (Arthur Farwell Collection, Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections, Sibley Music Library, Eastman School of Music, University of Rochester.)

their music programs, but he promised to come to Santa Barbara once a week to establish a chorus that would meet at the Recreation Center. The organizers briefly considered resuscitating the old Lobero Opera House for a home theater, but Fire Chief Endsley said the necessary repairs would be costly, upwards of $20,000, and it was too dangerous to use as it was.25

Week after week the number of participants in the Community Chorus grew. At the second meeting, Farwell had showed those who had not considered themselves singers that with a little instruction they could make real

music.26 By November 1919, the press reported that the musical people in Santa Barbara were all agog over Farwell’s successful leadership of the community chorus. Already boasting three hundred singers, the chorus continued to swell.27 By the end of November, the Community Chorus was ready to give a public program at Plaza del Mar.28

To promote the first concert, the press reported, “A snappy program of songs, including a number of the old familiar ones, will be tried at Sunday’s Plaza del Mar concert. There will be several added features in the way of diversity, as it is planned to make community singing one of the big winter treats in the city.” 29

Two thousand people gathered at the new bandstand at Plaza del Mar that Sunday, and song sheets were circulated to everyone. Everyone was urged to take part. “Those who had come merely to listen,” reported the newspaper, “found themselves drawn-in irresistibly to the current of the music.”

“It was in every sense a Pan-American gathering,” continued the reporter wryly, “the voices of the chorus rising in lusty and good humored competition with the enthusiastic rooters for the baseball game then in progress down the block. . . . It is apparent that the chorus is going to become a powerful rival of the Great American Game.”30

As Christmas approached, the chorus continued to swell in size. For their Christmas program on December 28 at Plaza del Mar, an orchestra of thirty musicians from Los Angeles was to play. The program included a section devoted to Spanish-Californian songs,

NOTICIAS 16

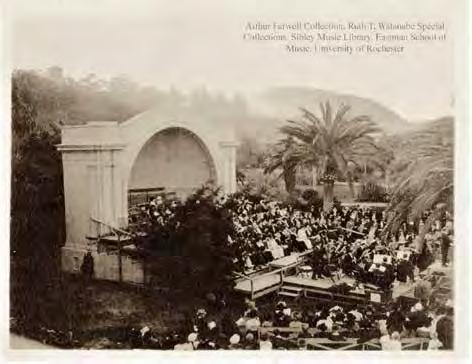

On December 28, 1919, the Community Chorus Christmas Concert performed on risers projecting from the new band shell at Plaza del Mar. They were accompanied by an orchestra of 30 musicians from Los Angeles.

In front of the bandstand, the audience stretched all the way to Castillo Street. The Potter Hotel can be glimpsed in the background.

17 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

with Arthur Farwell directing. Between 1903 and 1905, Charles Lummis recorded 450 songs on fragile wax cylinders. He hired Farwell to transcribe them. (Caroline and Edwin Gledhill portrait; Santa Barbara Historical Museum.)

for which Farwell had created special orchestration for this concert. The press claimed this would be the first time such songs were to be included in such a concert anywhere in America.31 These songs came from a collection of 450 songs gathered by Charles F. Lummis between 1903 and 1905 and recorded on fragile wax cylinders. At that time, Farwell had been hired to transcribe and harmonize the songs. Charles Fletcher Lummis was the colorful, eccentric, and influential writer and editor of the magazine Out West (previously Land of Sunshine). He was

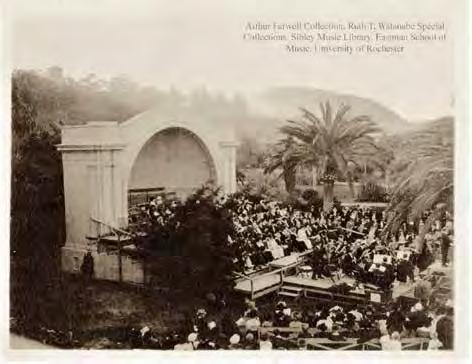

On April 18, 1920, the Santa Barbara Community Chorus performed at

an ardent preservationist of historic Spanish and indigenous peoples’ cultures as well as that of the later settlers of the West. Lummis and Farwell remained friends and collaborated on the sheet music publication of fourteen of these songs in 1923.32 Lummis was also a frequent visitor to Santa Barbara where he was a long time friend of the artist Alexander Harmer and his wife Felicidad Abadie.33 As the Community Chorus moved forward, the preservation of Spanish music became an important element.

The December 28 concert broke all

NOTICIAS 18

Ojai,

19

CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

SANTA BARBARA’S

The members of the Community Chorus who motored to Ojai take directions from Farwell.

Imogene Avis Palmer, who had led the wartime community chorus for a time, accompanied the chorus in Ojai.

records for attendance, and the chorus had grown to five hundred strong voices. The Morning Press reported, “To think that several hundred people, many of them without musical knowledge, could be brought together and welded into a chorus that would reach such magnitude seemed almost incomprehensible.”34

Three thousand people had joined in and were entertained by Spanish songs,

Christmas carols and the works of Handel, Haydn, Wagner, and Gounod. In spite of the glowing reports in the press, however, a misanthropic letter to the editor lambasted the audience for being cold, unenthusiastic, ungrateful, and ignorant. They had behaved as though they’d been reluctantly forced to come to the concert, said the writer.35 The truth, of course, is difficult to ascertain.

NOTICIAS 20

u Preparations for La Primavera

In November, part-time resident Hobart C. Chatfield-Taylor, a relation of Arthur Farwell and cultural promoter, returned from his Lake Forest home near Chicago with a friend in tow, Wallace Rice, a celebrated author, newspaper man, and playwright. Rice was spending the winter at Far Afield, the Chatfield-Taylor’s Montecito home. During Rice’s time in Santa Barbara he was entertained at numerous soirees, luncheons and dinners and he gave lectures at the public library and Chamber of Commerce on various themes, one of which was the importance of La Primavera. It was no surprise, therefore, when on January 30, 1920, the newspaper announced that Wallace Rice (who had been the official writer for the Illinois Centennial commission in 1918), assisted by Hobart C. Chatfield-Taylor and sometime local authors, Victor Mapes and Salisbury Field, had completed the masque to be given at the La Primavera festival.36

Much of the music for the masque was collected by Laurence Adler, music director and choirmaster of the Deane School in Montecito. Like Lummis, and perhaps inspired by him, Adler had been collecting early California,

Estelle and Hobart Chatfield-Taylor, an American writer, novelist, and biographer, were instrumental and intricately involved in bringing La Primavera and other cultural riches to Santa Barbara. Seen here circa 1940 in Fiesta garb, they continued to embrace the history of Santa Barbara. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

21 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

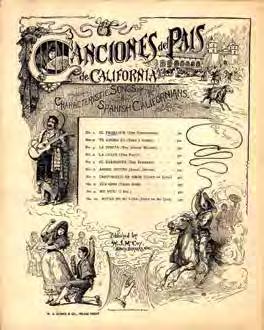

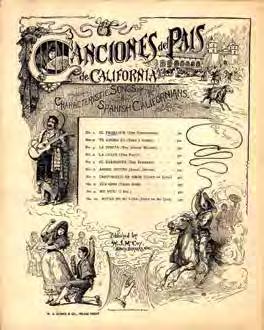

An early attempt to preserve, or at least replicate, the old Spanish songs was made by Professor Wm. J. McCoy in 1895. McCoy’s orchestra performed at the old Plaza del Mar and his students founded the Amateur Musical Club in 1892. Alexander Harmer designed the cover for the scores. “Te Adoro” was used in La Primavera. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

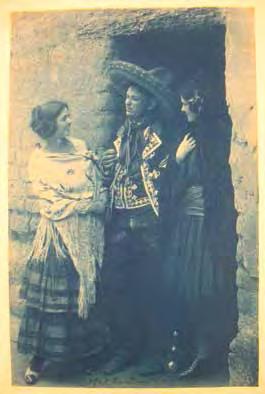

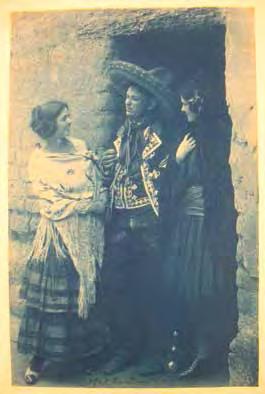

Harmer’s daughters, Ethel and Helen, had roles as “Months” in La Primavera. Photo is by Charles Lummis of Ethel, the artist Ed Borein, and Helen. Harmer often posed his friends in authentic historic dress to inform his painting. Borein’s first studio in Santa Barbara, in which he and Lucile lived for a time, was a studio at Harmer’s adobe on De la Guerra Plaza. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

Indian, and Spanish music, much of which was composed in Santa Barbara.37 Local residents opened their old leather trunks to retrieve the words and music of the beautiful old songs, which were largely in manuscript form. Music was contributed by Francisca de la Guerra Dibblee, Delfina de la Guerra, and María Antonia Arata, who, as a child, had been taught music by the mission padres.38

Adler created the scores for the ancient songs, sometimes by having the singers hum the tunes. Two local stenographers volunteered to design a method by which the music could be mimeographed, which was the first time that such a project was attempted in Santa Barbara.39 Chatfield-Taylor said that the collection and recording of this sweet old Spanish music would preserve some of the very best Spanish

NOTICIAS 22

Above: As an increasing number of Easterners settled in Santa Barbara, they enthusiastically embraced its romantic Spanish past and sought to celebrate and preserve it. Jarrett T. Richards, a transplanted Eastern attorney, wrote Romance on El Camino Real in 1914, a fictionalized history of real events, illustrated by Alexander Harmer. In this illustration, Carmelita and her beau Poncho play and sing a duet called Canción de la Ternura, (Song of Tenderness). Harmer most likely used his daughter Inez as the model for the 17-year old Carmelita. They are seated in a window of the De la Guerra Adobe. The aim of La Primavera was to preserve these songs and these stories. The Santa Barbara Historical Museum owns Inez’s dress and guitar, which are on exhibit. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

Below: In 1923, Charles Lummis and Arthur Farwell collaborated to produce what they hoped would be the first of a series of songbooks of old Spanish songs. Ed Borein, by then a local Santa Barbara artist, created the cover design. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

23 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

ballads. “The play with its romance and adventure and color can be thanked for having saved the music which might have died with the passing of the older families,” he said.40

Samuel Hume, the director of the Greek Theatre in Berkeley, was retained to help Rice stage La Primavera. 41 Arthur Farwell became musical director, and Irving Pichel, budding actor and director, was hired to play the role of the narrator, El Barbareño. The arrival of these luminaries in Santa Barbara fostered great excitement and several community members began urging the creation of a community theatre and art center to bring together all aspects of the arts.42

In a talk at the Rotary Club, Samuel Hume explained, “A community theater is the focusing point for big things. It eventually becomes a great asset in the city’s welfare. . . . After the regular work of the day is done comes leisure and a change for something more than mere recreation or amusement. We Americans have been too much given to letting others amuse us . . . we like to sit on the bleachers and see somebody else do the playing instead of getting out and doing our own playing. But beyond the need for earning our daily bread, lie beauty, philosophy, the happiness of others, and the welfare of the community of which we are always a part. Painting, sculpture, literature, poetry

NOTICIAS 24

Advertisement for the two-day Primavera Celebration (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

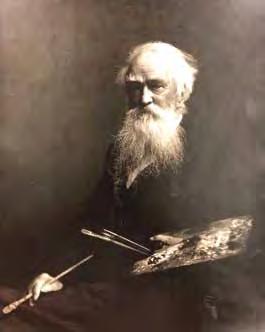

Alexander Harmer in his studio on Plaza de la Guerra. His painting of a fiesta at Casa de la Guerra hangs behind him. Harmer’s brush preserved the history of the Spanish Californios. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum).

The location of the outdoor theater created for La Primavera was in a swale on the block bordered by Santa Barbara, De la Guerra, Garden, and Canon Perdido streets, the site of today’s Laguna Cottages for Seniors. The photo shows the block in the late 1890s. At this time, the Riviera was mostly devoid of dwellings, but the Ramirez Adobe, (middle left) still stands today on the corner of De la Guerra and Garden streets. (Courtesy John Woodward)

music — vocal and instrumental —, architecture, dancing, tragedy and comedy; all seven of the arts, find expression in the theatre.”43

Recruitment for choral performers continued, and local musical experts like Laurence Adler; Helen N. Barnett, director of the Orpheus Club; and Imogene Palmer, former director and current accompanist to the Community Chorus, passed judgment on the applicants. Aiming for one hundred voices, the recruiters were pleased by the number of Spanish-speaking girls who were to be of great help to the directors and producers of the pageant.44

The site selected for the spectacle was in a draw between East Canon Perdido

and De la Guerra streets, just beyond Neighborhood House and north of Garden Street. Winsor Soule estimated that 4,000 seats could be accommodated in the swale in front of the 80-foot stage built against the rising hillside. Rice and Hume tested the acoustics and found them excellent.45 The old Gonzalez-Ramirez adobe home sat on the ridge above the stage, and for many years afterwards, a Mexican dance floor, bandstand and Fiesta café occupied the swale during Old Spanish Days.46 Today, Laguna Cottages for Seniors occupies the site.

u Viva La Primavera!

W

hen April 28 finally arrived, weeks of promotion had done their work. The following day’s headline blared, “PAGEANT MASQUE LA PRIMAVERA SHATTERS ALL PRECEDENTS IN SANTA BARBARA CELEBRATIONS.” Record breaking crowds attended the two performances, which opened with a greeting by El Barbareño, played by Irving Pichel.

“Sweet ladies, genial gentlemen, this day glittereth like a jewel brightly placed,” he intoned. “So come we hither to call back the Past when smiling nature at her kindliest ruled this newer Eden. Such ancient things ye’ll see, but chiefly, amidst our birds and flowers and butterflies, bright Primavera, spirit of this place, forever young, with blossomy dancing Months [of May].”

Primavera then speaks, though neither she nor the dancing Months can be seen by the other characters who are involved in their own ambitious pursuits. With the chorus and the orchestra hidden by the shrubbery to the side of the stage, Primavera and the Months dance to the strains of the first song, “Las Mañanitas.”

The parade of history begins when Primavera says, “I hear the footfalls on

Harvard graduate Irving Pichel was associated with Samuel Hume and the Berkeley Greek Theatre, of which he would become director before moving to Hollywood and a career as a film actor and director. His association with Santa Barbara began with La Primavera and continued through the early years of the Community Arts Players. Beginning with the 1926-27 season, he served as director of the Players for several years. The portrait is from the 1940s. (Wikimedia Commons)

my foam-laced strand of newer fates.” First come the explorers Cabrillo and Vizcaíno and then the missionaries who brought Christianity to the Chumash people. When the ancient pagan idol is thrown out, it returns as a duende, a corrupting trickster who causes strife throughout the years.

In Act II, Spain yields to Mexico, and in Act III Mexico yields to the United

NOTICIAS 26

States. Throughout both acts, singing, music and dancing predominate. The well-known Santa Barbara story of the lost cannon (Canon Perdido Street) is portrayed. And wouldn’t you know it, it was that duende who made those boys steal the American cannon. The play, such as it was, ends with the comandante’s daughter marrying the American officer who had collected the five hundred pesos penalty (Quinentos Street) for the theft. Then comes the wedding march written by Mrs. Herminia de la

Guerra Lee and the comandante says to the American bridegroom, “My daughter’s love has made your Flag mine own. Down comes yonder Banner, it is mine no more.”

At this point the play is essentially over and the Spanish dances of El Son, La Jota and La Contradanza lead to a grand finale danced by the entire cast to the singing of the choristers and the music of the orchestra. As the actors and dancers leave the stage, the American flag is raised and everyone stands to

27 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

The Months dance on the stage designed by Kem Weber of the firm of Youmans & Weber. He also designed the lighting for the evening performance. The chorus sits to the right behind a screen of bushes.

Above: “La Primavera” dancers is courtesy of the University of Rochester, New York, who gave the author permission to use photos from the Arthur Farwell Collection, part of Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections at the Sibley Music Library of the Eastman School of Music. All photos of Primavera come from this collection.

Below: The Months, invisible to the rest of the characters, watch as Viscaíno arrives and the Missionaries encounter the indigenous peoples.

sing the “The Star Spangled Banner.47 An elated Santa Barbara heaped praise on the spectacle performance, which was a rousing artistic success. Unfortunately, it was a financial failure. In June, the La Primavera organization sent letters to its guarantors saying they had a deficiency of $10,000 and that each investor needed to pay his share.48 Though the organization hobbled along for a few more years, it was never able to launch such a spectacle again. Nevertheless, it established the colors and logos for the Santa Barbara flag and led to the 1924 establishment of Old Spanish Days, which is now a nearly 100-year-old annual celebration.

Below: There were two performances, one during the day and the other at night. In this scene, the Spanish Missionaries bring Christianity to the local Chumash. Boys from the high school played the role of the Indians, and seminary students from St. Anthony’s played the role of the padres.

29 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

Mary Schauer, seen here as Primavera, was the daughter of the president of the Chamber of Commerce. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

The next day’s headlines boasted the success of La Primavera. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

NOTICIAS 30

u Santa Barbara School of the Arts

April’s La Primavera inspired the populace to advocate for artistic training. In May 1920, one hundred people met at the public library to discuss a proposed school of festival arts. Arthur Farwell explained that the school would be for all people, young or old, rich or poor. “All the branches of art required in the production of a festival such as Primavera, will be taught,” he said.

Others who spoke in favor of the idea were librarian Frances B. Linn, Marion Craig Wentworth, and artist Fernand Lungren, who said he’d been hoping for such a school for fifteen years because he wanted Santa Barbara to become a great art center. Over fifty people had already signed up prior to the meeting, and another fifty added their names to the enterprise that evening. 49

As the ground swell for the idea grew, a home for the school was found in a large adobe house at 936 Santa Barbara Street known as the Dominguez Adobe. “It is to be run on the cooperative community plan,” reported the press, “and so democratically managed that any man, woman, or child, may become a pupil and learn what he does not find in his everyday life, a school for the people, non-profit-seeking; a center and fellowship for the study of art.” 50

The school was to add beauty to people’s

31 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

The Dominguez Adobe at 936 Santa Barbara Street on the corner of Carrillo Street was renovated to house the School of the Arts. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum).

Local amateur and professional actors assisted Marie Burroughs in the benefit program for the School of the Arts. Even Community Chorus director Arthur Farwell took a role. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

lives and develop the intellectual and social needs of the community. It hoped to enable people to express personality and develop authentic personal character. “For one is in his real character only when he does the thing he wants most to do,” claimed the organizers. A bonus to the enterprise was the preservation of one of the quickly disappearing historic adobes of Santa Barbara’s Spanish past.51 This movement had taken hold of the community and several groups and people had stepped forward to help preserve the historic structures.

Throughout October 1920, names of potential teachers and courses seemed to change daily. By the end of the month, the organization, which had adopted the name Santa Barbara School of the Arts, advertised its potential of-

World-renowned portrait and mural artist Albert Herter, who, together with his artist wife Adele, had established an exclusive hotel named El Mirasol in Santa Barbara, was a major contributor in the development of all aspects of the Community Arts Association. Albert taught at the School of the Arts for several years and produced benefits for and acted with the Community Players, among other things. (Library of Congress)

ferings.52 That first term, Albert Herter was to teach a course in life art; DeWitt Parshall was to teach drawing and painting; Carl Oscar Borg and Dudley Carpenter, outdoor sketching. Marion Craig Wentworth and Edna Schmitt had charge of the drama department and were to offer classes in acting, voice, pantomime, story telling, extemporaneous speaking, and personal deportment. Other courses that were being considered were sculpture, architecture,

NOTICIAS 32

landscape gardening, various languages, music, poetry, and playwriting.53

The School opened in November 1920 and quickly added dancing classes, which were organized and taught by Miss Edith McCabe.54 She had been teaching dance in Santa Barbara since 1913 when she arrived from New York to take a position at the Gamble School for Girls. She soon opened her own business teaching social dancing like one-steps, waltzes and a new military style of the tango.55 She also taught aesthetic dancing (dubbed “fancy” dancing by terpsichorean-phobic news reporters of the time), and she offered classes in rhythmic exercise, perhaps an early version of jazzercise or zumba.56 McCabe would continue teaching dance in Santa Barbara well into the 1940s. By the end of the month the school was able to make its “formal bow” to

33 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

An ad for the last season the school would be housed at 936 Santa Barbara Street. After the 1925 earthquake, a new school was built on Santa Barbara Street farther down the block. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

Arthur Bliss, already a renowned musician, conductor and composer, took the town by storm in 1924-25, when he joined his father and family in Santa Barbara. He instituted many programs for the Community Arts Association and taught at the School of the Arts. He ended his time in Santa Barbara by playing the lead in Beggar on Horseback, the inaugural play of the new Lobero Theatre. When he returned to Great Britain, he took with him his bride, his co-star in Beggar, Gertrude Hoffmann. Bliss would later be knighted for his contributions to music in England. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

The Community Arts Association published a brochure outlining the plan for a new campus for the School of the Arts in May 1925, just before the terrible earthquake at the end of June. (UCSB Library, Special Collections, Community Development and Conservation Collection)

NOTICIAS 34

Lilia Tuckerman contributed a painting for the opening exhibition of the art gallery at the School of the Arts in 1922. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

the public at an open house in the renovated and modernized adobe. “The founders,” reported the press, “want to give an opportunity to find happiness and competence in self-expression to those who, for lack of such opportunity, might be bound by necessity to the wheel of drudgery.”57

The cost of escaping that tiresome wheel was nominal and even, in some cases, gratis. The instructors mostly gave of their time freely, or for very low fees. There was a need, therefore, for raising funds to cover costs. In March 1921, Marie Burroughs, prominent stage actress of the time, was brought to Santa Barbara to present a program of two one-act plays, and two scenes from Romeo and Juliet. Actors from the school and the recently formed Community Arts Players were to take the supporting roles. (Burroughs would return to

Clarence Black donated the professional lighting system for the first exhibition in the gallery of the School of the Arts. Black’s wife, the artist Mary Corning Winslow Black, painted en plein air and from her rooftop studio at their El Cerrito estate on Mission Ridge.

teach a drama course at the school in 1923.)58

Intended as a benefit for the School of the Arts, the performance, which was staged at the Potter Theatre, played to a nearly sold out house. Items for the stage settings were loaned by the public. Henry Levy had provided furnishings and hangings for “From Hour to Hour,” and the scenes from Romeo and Juliet played out against a great tapestry, insured for $17,000, from the home of Mrs. Oliver Dwight Norton. Other props for the elegant set included a

35 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

massive gilded bedstead and an antique mirror, all arranged by artist Robert Wilson Hyde.59

March 1921 also saw the School of the Arts create a little theater, which they dubbed the Workshop Theatre, in their assembly room. The idea was to have a tiny stage where short plays, new plays, and scenes could be tried. They wanted the atmosphere to be intimate and informal and hoped it would be a sort of laboratory for dramatic innovation.60 It was similar to the Little Theatre concept created by Winston Ames in New York. Ames had spent two winter seasons in Santa Barbara and had been impressed by the work being done here. His patronage would later be a great boon to the town’s cultural development.

61

The Workshop Theater became popular and several playlets were advertised to the public. It also became a venue for other organizations. For a benefit for Lincoln School, for instance, its PTA used the school to stage a demonstra-

tion of the old Spanish dances and music, along with foods, antique costumes, jewelry, and saddles. The dancers were quite antique themselves, so because of their advanced age and the fatiguing steps they would demonstrate, they only appeared in the afternoon performance.

62

The theater was also the venue for benefits for the School of the Arts itself. Georges (later Roger) Clerbois, the conductor of the Community Arts Orchestra and teacher at the school, arranged for a series of musicales to raise funds for the school.63

In March 1922, the School of the Arts opened an art gallery at the Dominguez Adobe. Twenty-three local artists displayed one painting each. Clarence Black, former president of Cadillac Motor Company and local resident, donated a lighting system of individual shaded lights.

The art work in the exhibit included Lilia Tuckerman’s Noche Serena, Ludmilla Welch’s Mountains near Santa

NOTICIAS 36

Edith McCabe’s students dance around the May Pole at McKinley School circa 1925. (Courtesy UCSB Library, Special Collections, Community Development and Conservation Collection)

Paula, Mary Corning Winslow Black’s San Juan Capistrano, Dwight Bridge’s Portrait of My Wife (Caroline Keck Herter Bridge), Thomas Moran’s Hot Springs at the Yellowstone, and paintings by many other familiar names from Santa Barbara’s artists’ colony.64 By its third year, the school had expanded exponentially and could not house all the classes being offered. The artist Charles Frederick Eaton loaned his studio building on Chapala Street near the beach for Albert Herter’s life study class. The May 1923 eclectic list of classes gives a sense of the scope of the school and the pressure for additional space for its enrollment of three hundred students.65

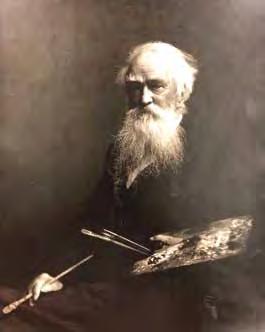

Today considered a world-renowned painter of the final decades of Western exploration, Thomas Moran settled in Santa Barbara in the 1920s, shortly before his death here in 1926. He exhibited Hot Springs at the Yellowstone at the School of the Arts, and painted many local scenes while living here as well. (Caroline and Edwin Gledhill portrait, Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

In 1923 it was decided to hire a fulltime director for the School. Arthur Farwell and then Bernhard Hoffmann had very briefly led the school, but the artist Fernand Lungren agreed to take on the directorship on a part-time basis for the first few years. The committee selected Frank Morley Fletcher, former director of the Edinburgh College of Art. Fletcher, who had studied with Lungren and Herter in Paris, had led his school to becoming one of the leading art institutions in the Great Britain. He was known for cultivating an appreciation and love of art among the workingmen of Great Britain, and was,

37 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

Banjo 1 Composition and Color 14 Dancing 66 Dramatic Art 21 Elementar y Drawing 3 Expression 2 French 8 Guitar 5 Italian 3 Interior Decorating 21 Life 21 Mandolin 1 Out-door-sketching 25 Photography 1 Piano 12 Music Appreciation 33 S hort Story Writing 14 S panish 20 Violin 10 Vocal 9 Vocal Coaching 5

therefore, imminently suited for the democratic ideals of the School of the Arts. Ironically, however, it was under his directorship that the school transitioned to a singular emphasis on fine arts by 1927.66

By 1924, the school had completely outgrown its facility, so the Community Arts Association purchased land farther down the block and hired the architectural firm of Soule, Murphy, and Hastings to design a new campus in the Spanish Colonial style. The plan was to move forward in stages, with the first one being the rehabilitation of the existing adobe for executive offices.67

When the 6.5 earthquake laid waste to the town on June 29, 1925, the old adobe was destroyed, and a more modest plan was implemented for the School of the Arts. A new campus of mostly wood frame buildings was built on Santa Barbara Street between Canon Perdido and Carrillo streets. The complex included a little theater but by 1927, the variety of courses was reduced to that of the plastic arts. The stock market crashed in 1929, and Frank Morley Fletcher resigned as director in 1930. A series of directors followed, but the school struggled during the Depression years and closed permanently in 1938.68

NOTICIAS 38

Seen here from the stage, is the meticulously restored Little Theatre (today’s Alhecama) of the former School of the Arts. Completed in 2018 by the Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation, the restored mural by Ross Dickenson adorns the back wall. Notable internationally known musicians such as Sir Arthur Bliss and Louis Persinger used the theater for rehearsal and classroom space. (Photo by Jim Bartsch, courtesy of Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation)

u The Quest

Though the Chamber of Commerce and local businessmen had been thoroughly discouraged by the lack of financial and promotional success of La Primavera in April 1920, another group in town became inspired to continue to build an artistic community. This civic-minded and culturally philanthropic group was mainly made up of wealthy transplanted Easterners and local artistic talents. They counted among them Clarence Black and his artist wife, Mary Corning Winslow Black; world-renowned artists Albert and Adele Herter; and Frederick Forest Peabody and his much-decorated wife, Kathleen Burke Peabody. John Percival Jefferson and Mary Jefferson, who hosted many musical soirees at their Montecito estate of Mira Flores, were also supporters. Serendipitously, their home would later become the site of the Music Academy of the West.

Still others included Herminia de la Guerra Lee, descendent of Spanish comandantes and author of the La Primavera wedding march, and Otto R. Hansen and Mary Catlin Hansen, whose continuing support of Santa Barbara’s cultural scene would lead to great things.69 Mary was an accomplished pianist and organized many

Samuel Hume played the role of Tragic Actor in The Cranbrook Masque in 1916 on the stage of their new Greek theater. (Courtesy Cranbrook Archives, Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research)

musical events. She had accompanied several community sings on the piano in 1917, and he had promoted the municipal orchestra in 1916 saying that there was a crying need for good music in Santa Barbara and asserting that a city orchestra would be a great attraction.70 Their continuing conviction regarding the importance of each, led to the eventual success of these earlier attempts.

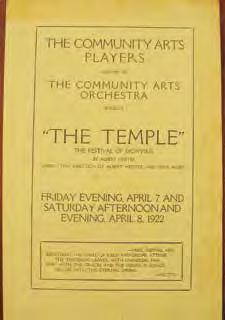

The group that formed in 1920 called themselves the Community Arts Association and their first goal was to stage another masque for the community. They created a headquarters in the old Primavera offices at 31 East De la Guerra Street. Like La Primavera, it was to be performed by local talent in an outdoor setting. Their plan was to create a permanent outdoor theater along the lines of the Greek Theater at Berkeley. To orchestrate the production, they brought Samuel J. Hume and Irving

39 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

Pichel back to Santa Barbara. Hume had been the director of La Primavera and Pichel had been both his assistant and the narrator of the masque. Hume and Pichel both worked with the Greek Theater and dramatic productions at Berkeley.71

Hume chose a masque written by Berkeley graduate Sidney Coe Howard, who would receive the Pulitzer Prize for drama in 1925 and a posthumous Academy Award in 1940 for the screenplay for Gone with Wind. 72 In 1916, Howard’s play, then called The Cranbrook Masque, had inaugurated the opening of a Greek theater at Cranbrook, the estate of George G. Booth near Detroit, Michigan, today’s Cranbrook Academy of Art. At the time,

Hume was the director of the Little Theater of the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts, under whose auspices the masque was given.73 Constance Binny of Winthrop Ames’ Little Theater in New York was in charge of the music.74 These connections would come to play in Santa Barbara.

Winthrop Ames, New York theater owner and director, spent two winter seasons in Santa Barbara. He extended one of his stays for La Primavera. He was so impressed with the artistic enterprise he witnessed that he offered his assistance and said he wished every city would experience such an awakening. The site of La Primavera, he said, had the potential for a Greek theater that would surpass that of Berkeley. By

The full cast at the outdoor theater at Cranbrook in 1916. The staging of the masque in Santa Barbara increased the pageantry by utilizing a natural setting and hundreds of participants. Courtesy Cranbrook Archives, Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research)

the time of The Quest, however, Hume had his eye on a new site for such a structure.

That site was the parkland of Plaza del Mar north of the bathhouse. Kem Weber, of the firm of Youmans & Weber, was a German designer who had moved to Santa Barbara in 1918 after being stranded in the United States in 1914 due to the outbreak of war.75 He designed the stage, costumes, properties, and all decorations of the performance. For The Quest, the costumes were designed and constructed at Weber’s Covarrubias School of Art.76 Weber had also been involved with La Primavera. Later, he would design sets for productions of the Community Arts Players and teach at the School of the Arts for a short time. He left Santa Barbara in 1921 to work for Barker Brothers where he would become one of the

Samuel Hume frolics with a fellow actor during a break from rehearsal at Cranbrook. (Courtesy Center for Creative Studies records, 19061982. Archive of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.)

Irving Pichel (far left) as Harlequin from the Renaissance episode and Samuel Hume (sitting far right on lower step) at Cranbrook in 1916. (Courtesy Center for Creative Studies records, 1906-1982. Archive of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.)

41 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

most prominent designers of modern furnishings in the United States.77

Weber’s work for the Community Arts group included the design of a wooden stage, screened by ice plant and erected against a curve of Leadbetter Hill (behind today’s tennis courts at Pershing Park/Plaza del Mar). Above this stage was a smaller one, similarly screened and connected on either side by diagonal steps. Weber also designed architectural features such as a fountain and arches between the upper and lower stages.78

Local additions to the production staff included Mrs. A. B. Barnett, conductor of the Orpheus Club, who became director of choral music. The Club itself was to sing “Alla Trinita,” a 13th century hymn employed in the Medieval scene and “Robin M’Aime,” an old French song, for the Renaissance scene. Mrs. L.D. Mosher, of the Santa Barbara State Normal School on the

Riviera, was to direct a male chorus of twenty voices singing a sea shanty for a scene in which mariner-explorers set out for the New World. They were also to sing a Gregorian plainsong chant for the Medieval scene.79

The trees separating the plaza from the slough at the base of the hill were removed and the slough was drained and then filled with seawater to form a lagoon.80 Frederick W. Leadbetter’s winding road leading up to his estate on the Mesa, the former Dibblee estate, was put into theatrical service for long processions of costumed actors.81

The Quest, which ran for three nights starting July 15, is the allegorical story of the search for love, song, romance, and beauty through the ages and ends with a rediscovery and preservation of each through the work of Drama. Samuel Hume opened the masque in the role of the narrator, the Tragic Actor. Mary Morris, who played several roles in the masque, wrote about the production in November 1920.

“The audience sat on the far side of the lagoon,” she said, “a thousand or more people in the broad field gazing up at what the mystery of that hillside would unfold. Suddenly a spot of light was thrown on the vast figure of the Tragic Actor standing alone some twelve feet high and clad in brilliant scarlet with a vivid blue mask. He spoke, then vanished with a clash of cymbals….”

Color, laughter, and song pervaded the production. For the Medieval scene, the long road winding down the hillside saw a brilliant procession of costumed Medieval citizens such as guilds’ mem-

NOTICIAS 42

The area of Plaza Del Mar and Pershing Park circa 1890 shows the slough that once lay below the hill. The Dibblee mansion and estate on the hill above the marshland is now the site of Santa Barbara City College. The Quest was staged at the base of the hill below the mansion, the site of today’s tennis courts. Remnants of the slough still flow in a concrete channel behind the courts. (Edson Smith Photo Collection, Santa Barbara Public Library)

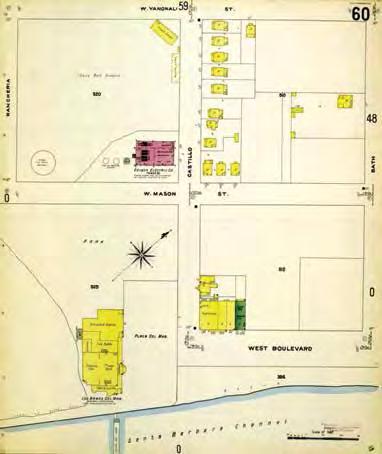

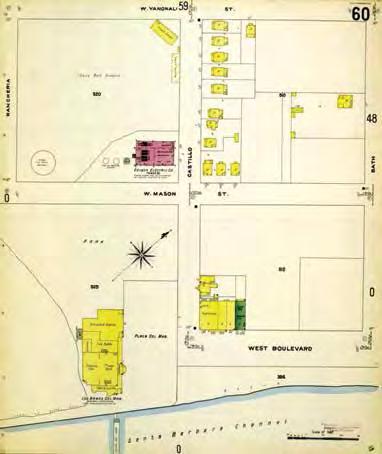

The 1907 Sanborn Fire Insurance map shows the 1893 Plaza Del Mar, the 1901 Bathhouse (burned in 1913 and replaced in 1915), the parkland that was added to Plaza Del Mar in 1899, and the 1903 Athletic Park (renamed Pershing Park in 1919.) (Library of Congress).

bers, prelates, doctors, lawyers, jesters, troubadours, and knights and ladies on horseback with bright caparisons and vibrant flying banners.82

Best of all, the new lagoon was employed to bring the actors in each act to the stage. Orpheus, in a flame-colored tunic, and Eurydice, in blue-green gown, were basked by green light as they returned from the underworld in a barge ferried by Charon.83 Later, Elizabethan mariners made their entrance in a ship’s boat, pulling oars to the tune of an old sea shanty, which began, “We’ll rant and we’ll roar like true British sailors; we’ll rant and we’ll roar o’er all the salt seas.” For the Italian Renaissance scene, gondolas filled with maskers, gave the impression of romantic Venice.84

The review the following day said it was one of prettiest plays ever presented in Santa Barbara, and that the local talent had acquitted themselves like veterans after a season on Broadway. “The Quest,” wrote the reviewer, “is a specta-

cle play. It has color, action, humor, and music. And it is set in, what some claim to be, the most beautiful outdoor stage in America.”85

The Quest was intended as a dedication of the Open Air theatre in Santa Barbara, and monies raised were to help develop the community theatre concept. But it was not to be. A week after the performance, the Community Arts Association announced that there was not sufficient interest to support a permanent outdoor theater. Nevertheless, the Association planned to continue because, though there had been many empty seats at each performance, the spectacle play had been seen and enthusiastically praised by townspeople and visitors of taste and discernment. Thus encouraged by the artistic success of the product, they decided to continue the experiment of producing plays in Santa Barbara and were arranging a dramatic performance for the middle of August at a different location.86

NOTICIAS 44

u Community Arts Players

The Quest had played for three nights starting July 15, 1920. For the fourth night, Hume had arranged for a performance of a medieval miracle play, “Abraham and Isaac,” which would be presented free of charge. Arthur Farwell and the Community Chorus agreed to lead the singing for the program.87 Farwell prepared a program of sacred and semi-sacred music that included French composer Charles Gounod’s “Send Out Thy Light.” The play portrayed the interrupted sacrifice of Isaac by the appearance of an angel. It was written in verse and, according to the press, contained much charm and beauty as well as dramatic appeal.88 Of the four characters in the play, Samuel Hume played Abraham and Irving Pichel, the Angel.89

The fledgling Community Arts Association decided that this smaller format, rather than expensive pageantry and out-of-town luminaries should be the way forward toward creating a community theater program. They planned to create a series of monthly trios of one-act plays. The first was

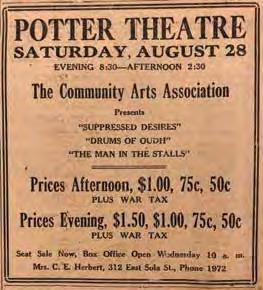

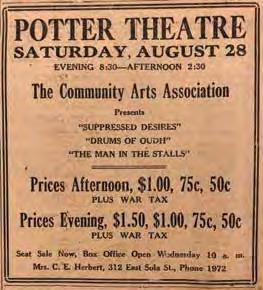

scheduled for August 28, and, thanks to the generosity of Edward Johnson and Aubrey Stauffer of the California Theater Company, they were staged at the Potter Theatre. The Association hoped that by the end of the year they would have aroused so much interest in locally produced drama that a community playhouse would become a necessity.90

The Community Arts group stated that their aim was to develop talent and stimulate interest in Santa Barbara along literary, dramatic, and other artistic lines and to eventually establish an indoor as well as an outdoor theater. “They hope the public will be interested in the production of good drama, presented by home talent, in a finished and artistic manner under professional direction,” reported the Morning Press. 91

At the end of July 1920, the executive committee had held a meeting at the home of Mrs. Otto R. (Mary Catlin) Hansen for the purpose of reorganizing and becoming a permanent committee to produce plays and pageants. With a $50 loan from Mrs. Hansen with which to start the productions,92 the group was able to move forward. Clarence Black became honorary chairperson and Mary Catlin Hanson became chairperson. Edward Johnson was vice chairperson; Aubrey Stauffer, stage director; Mrs. Michel A. (Elma Claire) Levy, secretary; and Albert Herter, stage settings.93

As the date for the first series of playlets approached, the organization made good use of the press, with articles and ads nearly everyday. They also tapped into the local artist community

45 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

for posters to advertise them. Carl Oscar Borg, Robert Hyde, Kem Weber, Douglass Parshall, Dwight Bridge, and Mary Catlin Hansen were among those local artists who painted posters for the plays.94 The movie theaters ran streamers advertising the plays, and giant Sepoys, which played dire fiends in one of the plays, paraded down State Street to entice attendance.95

The first of the three playlets to initiate the new effort of the Community Arts Association was “Suppressed Desires” starring David Imboden (Herter protégé and soon-to-be silver screen

star) as well as Gwendolin Whittingham, batik artist, and Mary Overman, lead singer from The Quest, who would be long associated with vocal programs in Santa Barbara. The second playlet, “The Drums of Oudh” was a mysterious and dramatic East Indian melodrama, and the third was “The Man in the Stalls” in which Inez de la Guerra Dibblee had a pivotal role. Albert Herter, assisted by David Imboden, created the lighting effects and settings, and Aubrey Stauffer, director of California Theatres, gave of his time to direct the production.96 The list of local residents

NOTICIAS 46

At the Colby residence in Mission Canyon, on a knoll between Rattlesnake and Mission creeks in 1915, Mary Catlin Hansen (standing center in front of woman with hat) and Otto Hansen (far right) pose with friends. Mary Hansen became chairperson of the Community Arts Association and loaned the group $50 with which to stage the first set of playlets. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

who gave valuable service to the production numbered in the hundreds. It was a true community undertaking.97

The popularity of the first set of playlets encouraged the Community Arts Association to continue the steps needed to become permanent. Their ambition was to tap into the latent talents of the people by giving regular training

Ad for the first set of playlets produced by the Community Arts Association in 1920 (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

One of the few known photographs of the front of the Potter Theatre features Father Villa’s band in their brand spanking new uniforms. The Community Arts Players used the Potter stage from 1920 until 1924. The theater was destroyed in the 1925 earthquake. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

47 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

along the lines of stage setting, costuming, makeup and lighting as well as acting. The work of training and producing the plays, however, was to be in the hands of professionals.98

With the success of the next group of playlets in October 1920, the Players won an audience. The Morning Press reported, “And again they did it. People who have said that any group of local people anywhere could not give a professional performance received the rebuff of their lives last night when they saw the finished manner in which the Community Arts association put on three one-act plays at the Potter theater before a large and appreciative audience.”99

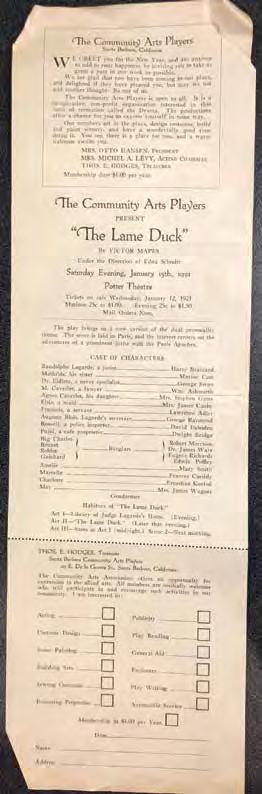

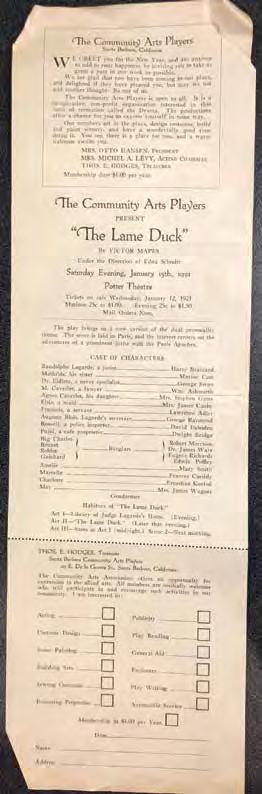

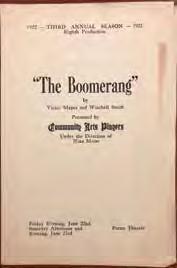

By January 1921, the Community Arts Players, under the direction of Edna Schmitt, felt ready to produce a full-length play, The Lame Duck. Afterwards, the reviews were glowing and pointed out that this play was truly a community venture. A local author, Victor Mapes, had written the play and local residents made up the cast. Local volunteers had charge of staging and management, local artists provided the scenery and sets and advertising, and local businesses loaned props and costumes.100

The first full-length play produced by the Community Arts Players was The Lame Duck by Victor Mapes. Locals who had roles in the production included David Imboden, Herter protégé and soon-to-be star of the silver screen; Mary Smith, wife of architect George Washington Smith; Dwight Bridge, Herter protégé and son-in-law; and Lawrence Adler, who had collected the music for La Primavera. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

NOTICIAS 48

The Community Arts plays were staged at the Potter Theatre, which once stood on the southwest corner of Montecito and State Street. Its original drop curtain, seen here, advertised local businesses and was quite controversial. Many well-heeled theater-goers felt the advertising cheapened the theater and vowed to never patronize any business that advertised on the drop curtain. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

SANTA BARBARA’S

u Branching Out

By the middle of February 1921, the Community Arts Association was once again considering the construction of a community theater building. They cited the success of recent productions and the pressure to include other mediums of artistic expression than drama to their program as well as the need for a centralized venue for the work of the

Association.

By the end of February, they added a Community Arts Orchestra to their purview. Founded by Adele Herter and funded by Clara Hinton Gould as a memorial to her husband, Frederic S. Gould, a string orchestra conducted by Georges (Roger) Clerbois was established. Concerts were to be held at the Recreation Center on Sundays.101

Albert and Adele Herter’s enthusiastic and generous contributions to the new organization were wide-spread and multifaceted. That they were greatly appreciated is revealed in the minutes of the annual meeting of May 10, 1921, when recording secretary Leila Weekes Wilson wrote of their overwhelming

Georges (Roger) Clerbois, together with Adele Herter and Clara Hinton Gould, founded the Community Arts Orchestra, thereby adding a music branch to the organization. The photo shows Clerbois with the string orchestra on the Recreation Center stage where they gave Sunday concerts. Adele designed the purple robes, and Herter Looms created the blue backdrop curtains. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

NOTICIAS 50

Flyer recruiting members for the Community Arts Association circa 1922 shows that all its branches are in place. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

51 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

and Bernhard Hoffmann and son at Casa Santa Cruz, their home near Mission Canyon. The Hoffmanns were instrumental in saving the old adobe homes and popularizing the Spanish Colonial style. Bernhard served as president of the Community Arts Association for several years and was most active in the Plans and Planting Branch.

gratitude of the “wonderful gift from Mr. Albert Herter of properties, scenery, and costumes of a magnitude of art and beauty” and that “the gift to us by Mrs. Herter of an entire community concert orchestra – fully formed—was something almost unheard of in any community.” 102

In September, the Santa Barbara School of the Arts affiliated with the Community Arts Association. Though it chose to retain its corporate identity, the unification would reduce overlap of functions, reduce expenses, and enable the two organizations to cooperate in

was a founder of the Music Branch of the Community Arts Association and served on the executive board of the organization as well. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

ways to the advantage of both. The enlarged organization would be governed by a board of seven (later ten) directors.103

A few days later, the Community Arts Association announced that it was formalizing its existence and had adopted a constitution and elected officers. They had also allied with the Community Christmas Committee, which had been founded by Pearl Chase, who would become a leading and unifying force for the entire organization.104

By early 1922, the last and final branch was added, Plans and Planting.

NOTICIAS 52

Adele Herter with daughter Lydia circa 1903. Adele

Irene

This branch sought to improve the city’s architecture and landscape. The Association also became involved with selling stock and raising funds for the Lobero Theatre Foundation. Initially, it would end up owning a quarter interest in the community’s theater, which would be completed in 1924.105

In spring 1922, the Association applied for a grant from the Carnegie Corporation and explained the importance of its mission. “The genesis of the Community Arts Association can be traced to the natural hunger of the human being for some form of artistic expression,” they wrote in the application. “The enjoyment and spiritual exaltation which comes from participation in Drama, Music, and allied arts is not reserved for those with advantages of superior education, but is native to the whole population…. While an enor-

The Community Arts Association officially incorporated in 1923 and developed a seal that reflected the breadth of the arts under its purview. In those days, no one objected to using saints as symbols of sectarian organizations. (Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

mous amount of money is spent each year on cinema and sporting events — these amusements offer passive recreation. Aside from dancing, they simply provide opportunity to sit and absorb…. Our children and youth need all that goes with play if we would make them strong and alert, further natural growth, keep them out of mischief and prevent the growth of that mass of twisted, morbid, troublesome, misanthropic men and women who so grievously burden society.”106

In November 1922, the Association received word that it would be receiving $25,000 a year for five years. At this point, the School of the Arts completely merged with it and received a portion of the grant monies. Thus guaranteed a steady base of funds, the work of the Community Arts Association was able to blossom and grow.107

53 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

In July 1922, the Community Arts Association advertised a contest for the design of a seal representing the organization. These are two of the designs submitted. Notice that one of them makes use of Lutah Maria Riggs’ design for the restored Lobero Theatre, one that was not implemented. (UCSB Library Special Collections, Community Development and Conservation Collection)

NOTICIAS 54

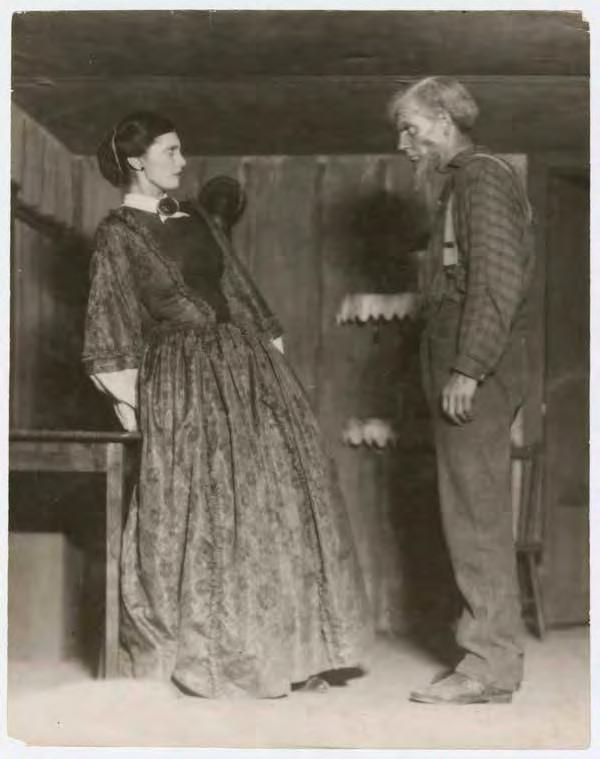

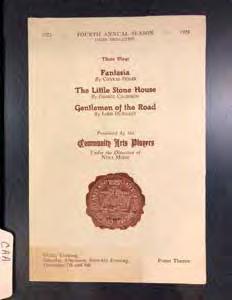

u Nina Moise: A Director Found Us

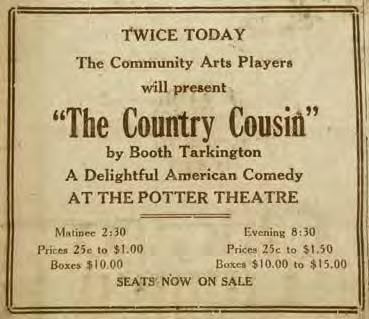

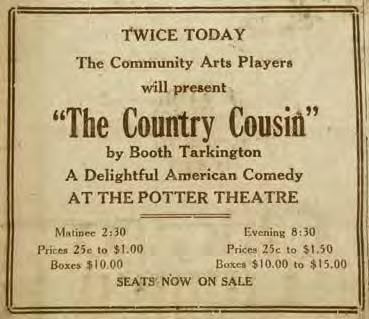

After the success of The Lame Duck in January 1921, the Players were encouraged to attempt another full-length play. They chose Booth Tarkington’s A Country Cousin for their February presentation. On January 30, however, they were shocked to learn of the untimely death of their director, Edna Schmitt, due to a burst appendix.108

Knowing that the Players could not continue rudderless, the Herters arranged to bring the experienced and up-and-coming director, Nina Moise, to Santa Barbara to take charge of A Country Cousin. Moise had previous experience as a director for the Provincetown Players and the Washington Square Players in New York. At the time, she was involved in various projects in Los Angeles and was working at Ince Studios in Culver City as an assistant film director. Nevertheless, she agreed to come to Santa Barbara to rescue the upcoming play, with which she was intimately familiar having previously played a role in it on the professional stage. 109

Nina Moise was an exceptional choice, and through her efforts, the

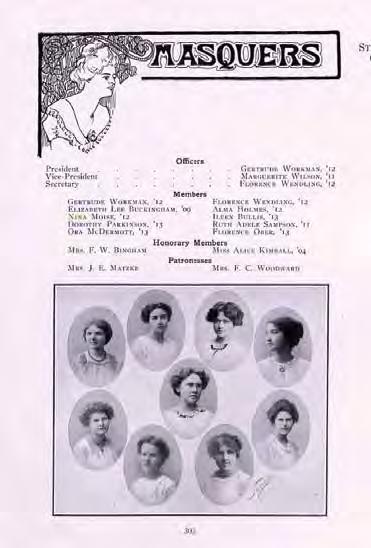

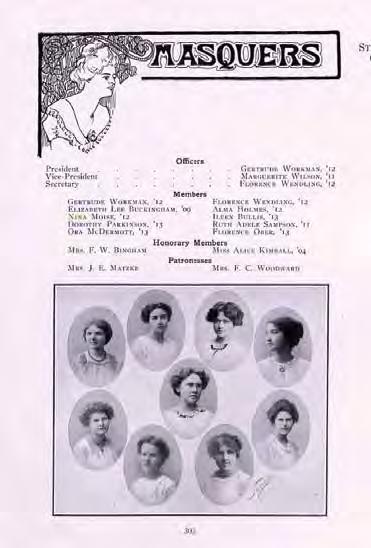

Community Arts Players thrived. Born in San Francisco in 1890, her interest in theatre was already well established at Girl’s High School where she played the role of Sahara in Princess Kiku, a musical comedy.110 Her dramatic interests were honed at Stanford University when she joined the Masquers and performed in several plays for which she received glowing comments.111

In 1916, Nina headed for the Big Apple, where she hoped to find work as an actress with one of the exciting experimental new playhouses popping up throughout the city. Instead, she landed directing positions with both the Provincetown Players and the Washington Square Players, and the direction of her life was set.

In a 1933 interview, she reminisced, “For my part, I have never sought the

55 SANTA BARBARA’S CULTURAL RENAISSANCE

Nina Moise circa 1922. (Ancestry.com)

job [of director]. I was an actress. Direction has always been thrust upon me. In those joyous old days of the Provincetown Players, when no one had any money and we were bursting with enthusiasm and honesty, they didn’t happen to need an actress but they did need a director. I worked for nothing the first year and staged several Eugene O’Neill, Floyd Dell, and Susan Glaspell plays.

“We were out to boost American playwrights. It wasn’t terrifically experimental and the author’s script was sacred. The second year I got $15 a week working for them at night and $25 a week with the Washington Square Players in the daytime, and never went to bed.”112

For their part, the Provincetown Players were happy to have her; in fact, she rescued them. In Edna Kenton’s memoir of the days of the Provincetown Players she says that the group