15 minute read

Voices

and provided a skosh of solitude but not too much. In 1998, at the cubicle’s peak, 40 million Americans worked in cubicle “farms.” You could customize your work cubby to the tune of two bobbleheads, three ironic Pez dispensers, one stapler, two cartoons, and one inspirational poster. Unfortunately the felt walls deadened not just noise but souls. Combined with the ubiquity of the buzzing, flickering fluorescent bulb overhead (which allowed plant managers to eliminate even more windows) I think the only reason more people didn’t hang themselves on the spot is the rickety dropped ceilings above would never hold.

In the ‘90s when America went digital, tech firms started to compete for the best minds so the old cubicle “veal farm for humans” needed to up its game. Tech office space was designed by child billionaires and it shows. Your baby boss wanted to make it comfortable for you to put in endless days and nights, so they provided perks like endless gummies, free bike share, and a chair that looked like a beach ball. This “NSA meets REI” fun workplace model reached its apotheosis with Google’s “Googleplex” in Silicon Valley. Which, like the dinosaur, put on its best show right before extinction.

The Googleplex in Mountain View is/was 20 million square feet of “worktivity” space (four World Trade Towers) festooned with bright colors and climbing nets so it feels less like the information gathering arm of the Fourth Reich and more like the oligarchy meets the bouncy house. Work at Google was supposed to feel fun and energizing, like burying yourself in the ball pit at IKEA, pre-coronavirus. With vegetative walls, fun office props, and lots of “hot desking” which sounds vaguely sexual, but not in a good way.

Sadly, today, with corporations like Google faced with sneeze-guarding

by Sharyn Main

Sharyn Main has 35 years of experience in philanthropy and the nonprofit sector, currently as the • Food from Staples: Twizzlers in bulk, milk cartons of Director of Climate Resilience at the Community Environmental Council. She grew up in Santa Barbara and is a fourth generation County resident. • • Whoppers w/out my wife lecturing me My petty larceny of office supplies No need to obsess over design flaws at the office – Local Lessons About Local Food: A Call to Invest in Local Food Infrastructure • who cares, not my problem Working at home: I have the worst boss in the world (me) F ood is such a basic human need, but as the COVID-19 pandemic has so sharply illustrated, despite our region’s bounty, our ever more complex food supply chain is not something we can take for granted. • Also that jerk at the office… In 2016, Santa Barbara County stakeholders (including the CEC) completed a is me comprehensive, community-driven strategic plan that provided recommendations for how we grow, distribute, consume, and dispose of food. The pandemic and its impact on our food system has put that groundwork to the test, spotlighting lessons we can learn from failing to adequately prepare for the current crisis.

One of the best ways to support and strengthen our local food supply chain is

What I WON’T miss about the workplace:

So Google, like every other The resilience, ingenuity, and grit it’s taken for these businesses to pivot is non-manufacturing corporation, impressive, but time was lost and perhaps other product lines sacrificed to make said it doesn’t expect or even want this happen. If our region had a grainery, seafood or meat processor, or other food to see its workers in corporeal form processing systems needed to keep the locally produced food local, we could any time before 2021, at the earliest. lighten our carbon footprint, keep more money in the county, have access to the Thus at least for the time being, the products, and food growers could avoid the price fixing that ensures corporate office as we knew it is toast. Which processors make a profit while local farmers and ranchers barely get by. pretty much returns work to where As cattle rancher and Oklahoma Farmers Union president Scott Blubaugh told it was 200 years ago, back in our CNN, the problem lies in how the corporate food processors treat their workers homes. and farmers, squeezing the growers to increase their profits. He suggests we,

Perhaps the biggest thing I “start enforcing antitrust laws that we used to have on the books... We need to get already miss about the dedicated away from this huge corporate control and international corporations controlling workplace is the same thing manour food system.” agers designed offices for in the We agree wholeheartedly. This is yet another example of the policy work we first place: so we could focus on need to do, and continue doing once we’re “back to normal.” work and be more productive. I This is an excellent opportunity for local impact investors to provide the capital feel like I need to wear a uniform so to build regional food processing capacity. This would have huge community my kids can clearly identify when benefits: helping to secure the local food system by investing in business, creating I’m “at work” and when I’m not. jobs, and supporting resiliency. Putting this in place will take political will and a These little rascals who are trying clear community vision for greater self sufficiency and resilience. to suck the life out of me need to We were just starting to recover economically from the Thomas Fire when understand that me staring off into COVID-19 hit. It’s clear that we can no longer send 95% of our products out and space doesn’t mean I’m in crisis/ import the same products back processed and packaged up. That adds costs – both rethinking my life, or, alternatively, financially and environmentally – and is a very weak link in our food system. available to pump up their bicycle The CEC has long been active in taking the steps needed to pursue a sustaintires. Staring off into space just hapable food system that balances the carbon equation to mitigate climate change. As pens to be 91% of the writer’s job. the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrate so clearly, working together

And now, if you’ll excuse me, I to secure our local food supply (while making sure that our workers are treated need to go pump up some bicycle fairly) is one of the most important ways we can help to ensure a more resilient tires. •MJ community. •MJ • The Voice of the Village • MONTECITO JOURNAL 41

to purchase regionally-produced food. Look for independently sold, responsibly sourced, fresh and seasonal food. As a result of COVID-19, the market is in flux, but our local farmers markets and some individual farmers, ranchers, and fishers are still operating with social distance guidelines in place.

While buying regionally is critical to maintaining a local food supply, that is only part of the puzzle. Like other short-term disaster response efforts, it’s only a Band-Aid to a longer-term problem. To have a truly sustainable and robust local • • • Cannot show up at meetings in underwear The office fridge – possible actual birthplace of coronavirus “Food” from Staples food system that is less vulnerable to outside forces, we need to promote investment in and a regulatory structure that encourages smaller scale, local and/or regional food processing. Local food needs to stay local. Under the “old normal” circumstances, growing food here and then transporting food for processing is highly fossil fuel intensive and wasteful. When cracks in that system start to surface, as they have recently, it becomes even less efficient and even more illogical.

It will take effort and time to begin to regionalize our food processing, but it • Petty larceny can be done. • Wood grain on any material For example, the Thomas Fire and the subsequent debris flow delayed White other than wood Buffalo Land Trust in harvesting their persimmons and getting them to market. Rather than let the fruit go bad, they created a persimmon vinegar product with a local distillery and solidified a new business venture. We’re seeing similar 20 million square feet, the price tag examples today: distillers and other small manufacturers are transitioning their of creating a city-sized salad bar but equipment to create emergency products like hand sanitizer and personal protecwithout salad is a non-starter. tion equipment.

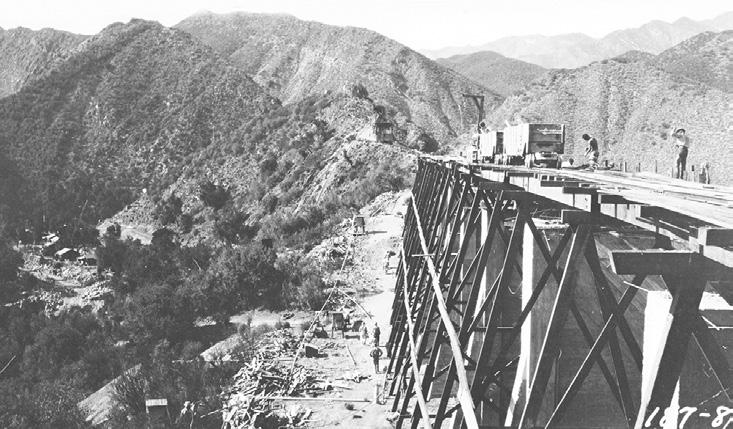

Construction begins on the Juncal Dam, circa 1920s (photo courtesy Montecito Water District)

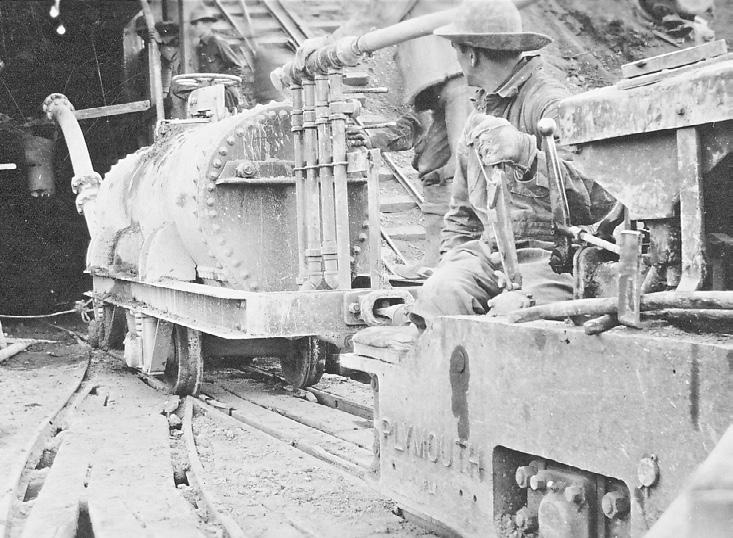

Drilling the Juncal Dam’s Doulton tunnel (photo courtesy Montecito Water District)

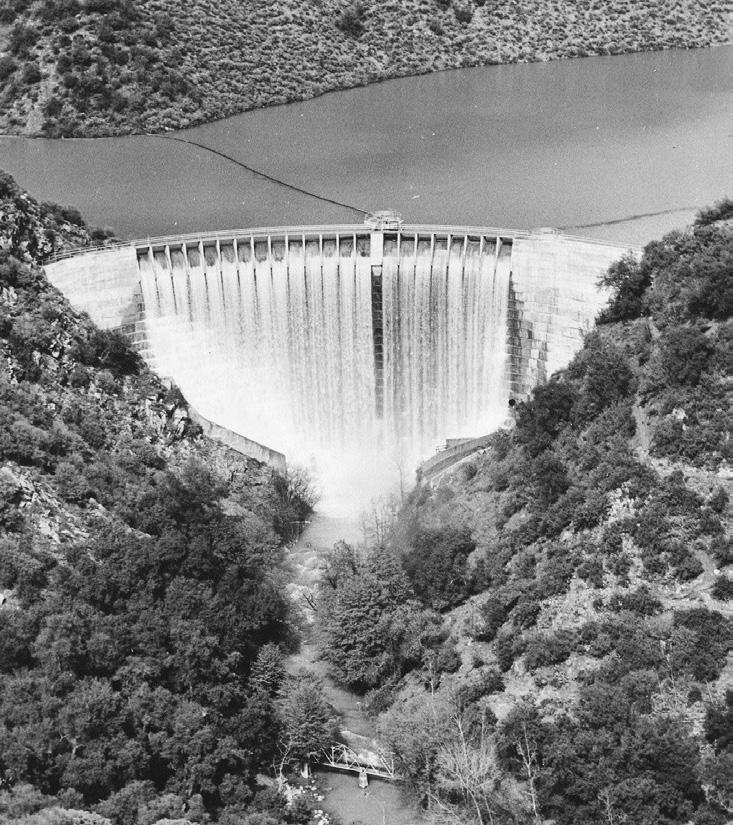

first major series of water projects, a series of reservoirs and tunnels carved into the terrain, including the Juncal Dam project which featured a 60-million-gallon reservoir, an 11,376- foot long tunnel, 35.64 miles of castiron pipe and no less than 340 fire hydrants. The reservoir and dam took nine years to build and cost taxpayers a grand total of $2.6 million ($39 million in today’s dollars), according to an October 1930 article that ran in Western Construction News. The story referred to Montecito as a “high-class residential section” lying immediately east of Santa Barbara where in recent years “the struggle for water” had become “acute.”

Just on schedule, Montecito began to run out of water again about 30 years later (is that why mortgages are 30 years?), and in 1958, MWD responded with the opening of the Bradbury Dam, which created a second reservoir, Lake Cachuma, which remains MWD’s largest local reservoir. Everything worked great until California experienced a different epic drought that lasted for two decades. In 1973, Montecito declared a water emergency, and the next year refused to issue any new water permits for the next 20 years, a period of water scarcity that led to a rush on the drilling of private wells and the gradual depletion of its aquifer.

A March 1980 report on Montecito’s underground water basin found that the volume of water pumped from private wells each year had plummeted from 1929 to 1979, from a high of around 1,700 acre feet to less than 750 acre feet per year, with over-pumping of wells too close to the beach having resulted in the intrusion of salt water. To fix that problem, the report recommended a limit on local well pumping as well as “an aggressive program of monitoring existing coastal wells.” Historically speaking, the first half of the1980s were relatively kind to Montecito’s water supply, with the groundwater basin reaching its historic height in 1983. But by the 42 MONTECITO JOURNAL

mid-1980s, the ground was drying up again. An August 5, 1987 report warned MWD against constructing a line of municipal wells along the coastline, arguing that the only way to find water would be to drill much deeper wells. A subsequent hydrological assessment commissioned by MWD in the early 1990s recommended that the district look to other, more remote sources of water. “It is recommended that MWD not increase pumping duration,” the report stated. “The current five days on and two days off schedule,” the report concluded, “does not allow full recovery in two days.”

Voters Weigh In

By 1991, both Montecito and Santa Barbara were locked in yet another epic, drought-related water shortage. For the second time since county voters were first asked about state water in 1979, Montecito residents were given the opportunity to approve either a desalination plant in Santa Barbara or an agreement to purchase state water from California’s State Water Project (SWP), a series of pipelines constructed in 1968 which brings water hundreds of miles from north to south through the Sacramento River Delta.

Originally, a so-called “poison pill” in the language of the voter’s desal initiative existed that would have allowed whichever plan that received the most votes to proceed while blocking the runner-up. However, the crucial verbiage was missing from the final draft of the desal initiative’s signature petition. More than 80 percent of voters approved the desalination plan, which was backed by the Environmental Defense Center (EDC), while about 60 percent of voters approved the proposed deal to purchase state water. “A grand compromise was reached,” said Carolee Krieger, who campaigned on behalf of desal for EDC and now represents California’s Water Impact Network (CWIN), which still supports desalina

A Mack truck in action (photo courtesy Montecito Water District)

The nearly completed dam (photo courtesy Montecito Water District)

tion. “The mix-up,” she said, “enabled both plans to go forward.”

According to Krieger, the main proponent of the SWP within the Central Coast Water Authority (CCWA) was the Santa Maria Water District, which needed as much water as possible for agriculture yet lacked the financial leverage to negotiate with the SWP by itself. Santa Maria controls more than 50 percent of the vote on the CCWA board. From 1991 to 1995,

Jameson Lake begins to form (photo courtesy Montecito Water District)

The completed project (photo courtesy Montecito Water District)

Lining the Doulton tunnel (photo courtesy Montecito Water District)

by which time CCWA’s headquarters had moved from Santa Barbara to Buellton, Krieger attended the agency’s board meetings. What she learned during those years soured her on both the SWP and regional water politics. “The CCWA has been trying to get the contract for state water away from the county of Santa Barbara,” Krieger said. “This would mean not only that South County would lose control to Santa Maria, but that we would have to pay any debt through our property taxes if there was a default on the agreement by any water agency. Nobody has any idea this has been happening.”

Tom Mosby served as MWD’s general manager from 1990 until 2016. He remembers sitting in an early 1990s board meeting where Santa Barbara water officials asked counterparts in Montecito and Goleta to commit to a long-term desal deal. “You guys told us to build the desal plant,” the officials said. “Here’s the contract: Sign it.” According to Mosby, an uncomfortable silence followed. “The board,” he recalled, “was like, ‘Are you kidding?’” Ultimately, Mosby said, Montecito and Goleta agreed to pay about $1 million per year for a period of five years simply to have a backup supply of desalinated water. Because of substantial rains during those years, however, none of that water was ever needed. Instead, Montecito and other local water districts that make up the Central Coast Water Authority (CCWA) agreed to purchase $6 million worth of state water per year, a deal that continues to this day.

To Desal or Not to Desal

Because the much-vaunted State Water Project was a relatively late arrival to the list of projects with claims on California’s water, Montecito’s claim to state water is far down the list of preferred customers. In any case, Montecito didn’t begin to receive its annual allocation of state water until 1998. “At first, we didn’t really need the water, because we had an El Niño season and one of the highest rainfall years on record,” Mosby recalled. As usual, everything went well until California hit another epic drought in 2014. “What happened that year surpassed anything we had ever seen on record,” he said. “The previous biggest drought was from 1947 to 1952, but this was far worse, and we had 1,000 more service connections since then because the community had grown.”

All of a sudden, Montecito found itself in a position where there was no rain, the century-old local reservoirs were bone dry, and state water wasn’t capable of making up the difference in demand because California could only allocate five percent of the contract amount to each of the 29 contractors, including Santa Barbara and Los Angeles. “We set records of demand in the middle of the drought, and then we had no winter weather,” Mosby said. “All of a sudden we had a significant number of more people being served and no conservation measures in place, and that’s why the tiered water system was finally put in.” For several months, MWD held up to three board meetings per week to discuss different plans to both put in place conservation measures and obtain more water. “That’s why the tiered water system was finally put in place to encourage conservation,” he said. In March 2014, MWD warned customers, especially heavy consumers of water, that they would have to cut back. That month, no fines were issued, but in April, although 80 percent of water users were told they could continue to use the same amount of water, MWD began to institute penalties for anyone within the remaining 20 percent of customers who went over their allocated monthly allowance of water.

“It worked,” Mosby said. “The change in water usage over the next two months was a decrease of 50 percent. It was incredible. It wasn’t the Water District that did this, but the community itself, which listened to where we were and got the message to use water in accordance with the new rules. I was very impressed: They stood up and stopped using water and allowed us to get through the drought. Montecito is in a much better stance today than in 1990,” Mosby concluded. “This has nothing to do with desalination or a dwindling water supply, but with the ability of the public to realize over time just how important it is to conserve water.”

But not everybody agrees that the water rationing which MWD instituted under Mosby’s tenure was the correct solution. And as previously reported in this series, the subsequent controversy over water rationing led directly to Montecito’s contentious 2016 elections over the future of the water board. It also led to the end of Mosby’s career.

Next week in MJ’s ongoing series on Montecito’s Complex Water World: A deep dive into desalination. •MJ MONTECITO JOURNAL 43