7 minute read

Form Drawing

DEVELOPING THE MIND AND BODY THROUGH THE ESSENTIALS OF FORM By Kathleen Taylor

Crown above, earth below, desk before, I am ready to go. Paper held, pencil in hand, I am ready to draw Straight lines and curves with my steadiest hand.

Advertisement

Waldorf Form Drawing Verse

Johannes Kepler (1571-1680) said: “...God in His ineffable resolve chose straightness and roundness in order to endow the world with the signature of the Divine. Thus, the All-wise originated the world of form, the total essence of which is encompassed in the contrasts of the straight and rounded line.”

When I began my journey as a teacher, I was working as an assistant in a second-grade class. The class was struggling in many ways. One of my tasks was to take a boy out of the classroom for a portion of the morning as he was not able to be in the room without causing huge disruptions. So, what was I to do with him? I had no idea. Luckily, a more experienced colleague suggested that I work with him in form drawing. Every morning, he and I would go into an empty room together and work on creating symmetrical forms. This boy, who could single-handedly throw off an entire lesson, would sit and focus easily for 20 minutes on form drawing. He would get into the work and then begin to tell me all the things that were going on for him at home, including a contentious divorce between his parents.

Waldorf education was new to me. I was still learning its subtle powers, but I knew something was changing for this boy as he worked on these simple forms. The work settled him and centered him. Afterward, he was able to rejoin the class. He was not suddenly an easy student but was able to be in the room with his peers and learn. I will never know if what helped was time to share his feelings and thoughts in a quiet space, or the practice of the drawing. Most likely, a combination. However, I have also found that if I need centering, practicing these balanced and harmonious forms works.

The founder of Waldorf education, Rudolf Steiner, introduced form drawing in 1919 as a new subject for curriculum. It is drawing that is non-representational; it is not a picture of a “something.” Form drawing was intended to address the need for movement, exercise manual skills, and help develop a sense of form. Steiner also saw it as preparation for writing for those just beginning their journey through the grades.

Every teacher prepares for many hours for that wonderful first day of first grade. The first lesson is a form-drawing lesson. It is the only lesson for which we are given a clear description of what should be taught. We teach the holding of the crayon, and the drawing of the straight line and the curve. From this very first lesson, all our drawing, writing, and later, geometry, flow. This is the beginning of creating something on a page with a crayon or a pencil, and later a pen.

In many places, Rudolf Steiner expresses the need to develop the intellect through the artistic. He writes, “It is meant, that especially in the very young child, that the intellect, the intelligence which works isolated in the soul, ought not yet to be developed. How

ever, all thinking ought to be developed by means of the visual, the pictorial.” As teachers, we work with this idea throughout the education. We are always asking ourselves, “How can I bring this lesson alive through the imagination?” Form drawing is one avenue that develops through the grades.

In Grade 1, the teacher leads the students in creating shapes and running forms that may be acted out in class and then put onto paper. For example, the form may develop out of the swirling brook followed by a fairy tale character in a story. Working with these forms helps increase an awareness of different directions in space.

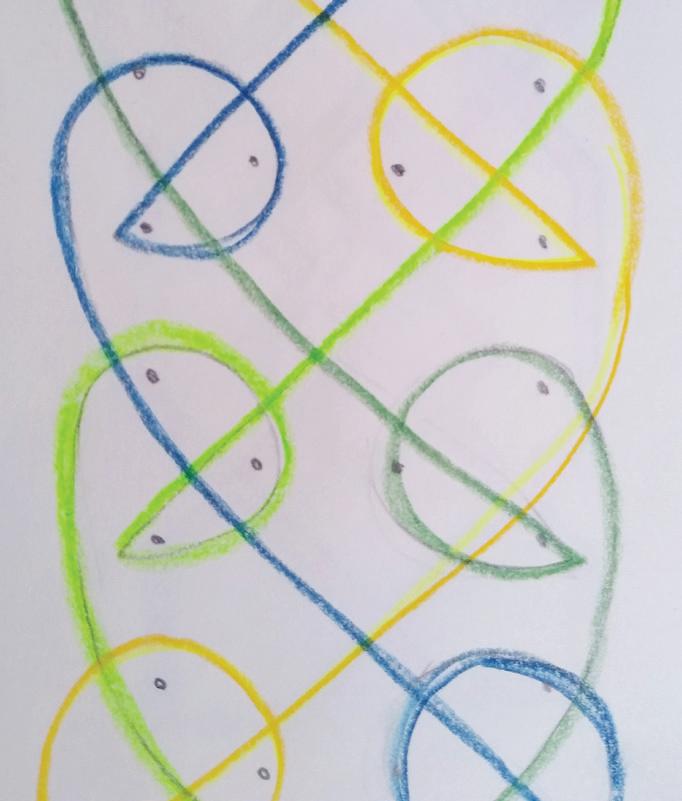

In Grade 2, the forms take on a new dimension: symmetry. Now the forms are created on one side of a midline and a mirror image is created on the other side. Soon reflections in all four quadrants of a page are drawn. This requires flexibility in thinking. One must be able to move the picture in one’s mind first, then draw it on the page. Steiner described form drawing as the means by which inner seeing can be cultivated in such a way that thinking can emerge without having to be drawn down into the intellect.

Once students have mastered symmetrical drawings, they are ready to work with asymmetrical forms. Now the students must complete a form to create balance and harmony. This requires more independence and imaginative mobility. Giving one side of a drawing and allowing the student to complete the drawing “arouses in them a feeling for form that will help the children to experience symmetry and harmony… Through the balancing out of forms, the child will develop observation that is permeated with thought, and thinking that is permeated with imaginative observation. All of the child’s thinking will become imagery,” writes Steiner in the Kingdom of Childhood. In this way, form drawing helps students become skillful in imaginative and pictorial thinking.

What, specifically, is pictorial thinking and what is the use for it? I once talked with a Waldorf alumni who was in college. He was taking history courses at the time and was marveling over how many of his classmates were struggling to remember the events and consequences that they needed to recall for the class. They asked this alum how he was able to remember it all. He replied simply that he formed pictures and could see it all as images and stories and did not find the need to try to memorize the material. Later he applied the same to his medical school courses. Rudolf Steiner shared this about memory in A Modern Art of Education: “Here are the golden rules for the development of memory; the perceptibly artistic builds it up; activities of will strengthen it and make it firm.”

Form drawing continues to develop imaginative thinking through Grades 4 and 5. Fractions and ratios can be worked creatively to help students develop a feeling for them. In science, we look at the many forms of crystal growth. This supports their later intellectual understanding of math and sciences.

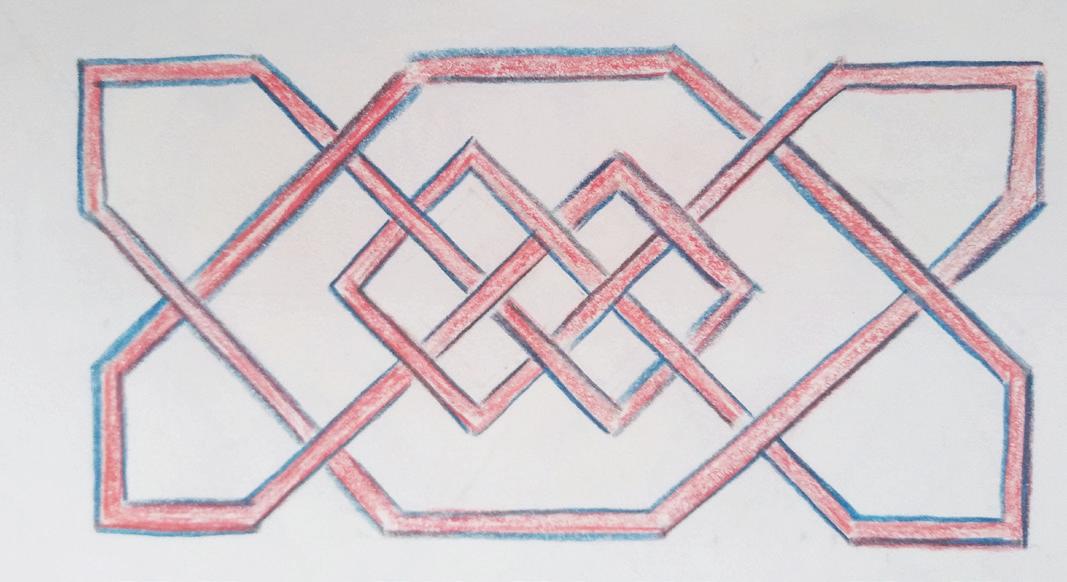

Cultural groups throughout the world also have forms to which they are deeply connected. When we see Celtic knot work, we recognize it as connected to the Celtic people. When we see Inca designs, we feel something different than we do when we see knot work. Working with the artistic forms of a culture can help us develop a feeling for the soul of a people or culture. As Waldorf students study the Ancient cultures of India, Persia, Mesopotamia, and Greece in fifth grade, they compare them through a feeling found in working with the forms that each of these cultures developed.

By Grade 6 and onward, form drawing becomes the study of geometry, using tools and precision the students already have, to learn about the relationships between forms as well as their beauty and harmony. Geometry comes alive when we work with the geometrical forms of nature. The student who has been honing an eye for form and balance can readily pick out these natural phenomena, and the golden ratio means more than simply numbers. Van James, a longtime Waldorf teacher shares in The Secret Language of Form: Visual Meaning in Art and Nature, “Even if they do not become artists, architects, engineers, or designers, such a grasp of the language of linear form will translate into a rich and beneficial experience of the relationships and patterns that exist among all things in the world.”

Taylor is the Grade 7 teacher at the Santa Fe Waldorf School