7 minute read

Bill Orzell

The Saratoga Baths on Phila Street

WRITTEN BY BILL ORZELL

A semi-detached portion of the bathhouse was the covered walkway along the building’s west side which was labeled ARCADE TO BROADWAY.

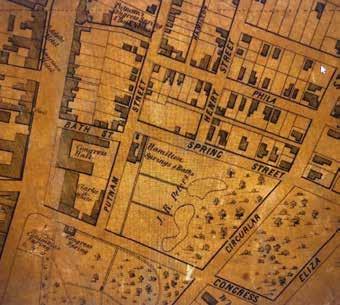

Phila Street originally did not intersect Broadway and terminated on Putnam Street, which was the reason the Arcade and Arcade-walkway was necessary to connect the Putnam Spring to Broadway. Map; Library of Congress. The architecture of Saratoga Springs is remarkable, and the tangible link to our past. However some gems have been lost through the ages, due to fire and folly. One such wonder was the Saratoga Bath House, at 25 Phila Street. The Putnam Spring was originally tubed in 1835 by Lewis Putnam, the son of Gideon Putnam. Lewis Putnam passed away in 1873, and in 1879 his heirs sold the property to Harry M. Levengston, locally described as “a well-known capitalist.” This entrepreneur, along with his son Harry Marcus Levengston, Jr. (whose first name frequently appears as Harrie), in 1889, began construction of a colossal Romanesque Revival edifice of masonry and tile to offer mineral baths, which were in high demand at the end of the nineteenth century. The ‘Saratoga Baths,’ using the tonic Putnam Spring, provided immersion therapy in naturally carbonated mineral water, a delight for mind and body. It was considered a treatment for heart disease, high blood pressure, arthritis, rheumatism, gout, neuritis and even obesity. Harry M. Levengston, Jr. was one of Saratoga’s leading Gilded Age sportsmen, an impressive marksman and winner of many shooting tournaments. Mr. Levengston and his son moved their families to the Spa after their important purchase on Phila Street, and they originally domiciled on Circular Street. The first step in the bathhouse creation was to retube the Putnam Spring, which resulted in the water rising to three feet of the surface, providing a well rather than a flowing spring. Without artesian flow, the mineral water was pumped through the bathhouse. Period accounts described the building as being the most complete structure of its kind in the country. It was two stories with a basement. The front elevation combined Oxford bluestone and Perth Amboy brick. The interior was finished in marble and fine woods in harmony, and provided separate facilities for men and women. The main entrance to the building was through an impressive round arch, flanked by Ionic columns, and supported an attractive architrave, incised with the words SARATOGA BATHS. A semicircular awning could be deployed from the archway on bright days. Just inside the front door was a reception room where the staff would greet a visitor as the effervescing mineral water of the Putnam Spring bubbled up in a large display bowl. Another distinctive feature of the first story was the oriel window supported by a hemispherical corbel below, with four Ionic colonnettes supporting the falcate hood. The other windows on the first story used the ledge that separated the bluestone from the brick as their sill, and a lintel formed by a stringcourse of vertical brick and projecting keystones.

Saratoga Baths fenestration of second story windows where surrounds were highly decorated pilasters, separated by rosettes, and surmounted by a façade of elaborate ornamental detail of repeating divisions of garland and angelic female faces.

Saratoga Baths oriel window supported by a hemispherical corbel below and incorporating four iconic colonettes to support the falcate hood.

The Saratoga Baths roof line featuring two pyramidal tile corner hip roofs, joined by a center gable. The center roof portion contained two imposing dormers. All roof ridge portions were capped in terra cotta tile, with the end points decorated with a cresting pointed ornament or finial. Two enormous chimneys soared up through each corner roof, where the masonry was laid-up with pleasing tuck-pointed arched reliefs and decorated with the same garland festoons as the cornice. The organization and design of the windows, or fenestration, on the second story was much more complex. These window surrounds were highly decorated pilasters, separated by rosettes, and surmounted by a cornice of elaborate ornamentation, repeating swags of garland and ovals containing angelic female faces. The roof line of the bathhouse was reminiscent of a chateau in style, featuring two pyramidal corner hip roofs, joined by a center gable. The center roof portion contained two imposing dormers projecting from the sloping gable roof and covered by its own separate roof, each housing a leaded stained glass window. All roof ridges were capped in terra cotta tile, with the end points decorated with a cresting ornament or finial. Two enormous chimneys soared up through each corner roof, where the masonry was laid-up with pleasing tuck-pointed arched reliefs, and decorated with the same garland festoons as the cornice. The front elevation quoins were set back and neatly dressed into the secondary façade of the sidewalls. A semidetached covered walkway along the building’s west side, labeled ARCADE TO BROADWAY, protected visitors from the weather and preserved the original connection from Broadway, through the Arcade Building to the Putnam Spring. The senior Mr. Levengston passed away in 1906 at his son’s home on North Broadway at the age of 85. He was fondly remembered for his generosity to charity. An important development in Saratoga Springs during the early years of the twentieth century was the conservation of the springs and mineral waters, which were being depleted by commercial exploitation. The Saratoga Springs Reservation was begun by Spencer Trask, and continued by George Foster Peabody, after the former’s untimely death. The Reservation concept had New York State acquire the land that held the natural fountains. A source of great contention for the Reservation was the preservation of the underground connectivity of the various wells and springs of the mineral water basin. The Commissioners of the State Reservation outlawed pumping of the mineral waters, which impacted the operation of the Saratoga Baths. In 1911 Mr. Levengston and ten other operations sought compensation from the Reservation through the legal process. The State offered to supply the Saratoga Baths with the overflow water of the nearby artesian Hathorn Spring, instead of the old Putnam Spring, with its widely accepted curative powers, which required mechanical lift.

New York State Archives image of the Saratoga Baths 25 Phila Street Saratoga Springs, New York. Main entrance from Phila Street of Saratoga Baths.

Saratogian 02/22/1928

Coley’s Restaurant and Oyster House at 19 Phila Street with the entrance (under the deployed awning) to the Putnam Spring, before the Levengstons’ constructed the Saratoga Baths. Photo circa 1881, courtesy SSPL. The wrangling between Mr. Levengston, and his beliefs about the old Putnam Spring which he had learned in his many years of operating the Saratoga Baths, and George Foster Peabody, armed with the new science of the State Reservation, played out on the pages of the local newspaper. In 1915, the Commission acquired the Saratoga Baths, renaming them the Kayaderosseras Baths. They found it important to provide year-round availability of the mineral waters from a central location in the community. New York State made a shift in the administration of the Saratoga Reservation in 1916, placing the organization under the Conservation Commission. With the First World War behind the nation, the Spa City prepared itself for increased visitor traffic, and the Conservation Commission added a laundry in the bathhouse basement. The dynamic stress created by the rotational heavy duty laundry equipment in the bathhouse, as well as the enormous water weight of the second story pools and attic storage tank, combined with the corrosive effect of the mineral water, all had a negative impact on the structure. The 1920 Annual Report of the Conservation Commission detailed the replacement of the storage tanks and the entire plumbing system at the bathhouse. The Report also contained an official disturbing revelation: the foundation was failing. Extensive stabilization repairs carried out made clear the importance of the downtown bathhouse. The always welcome annual advent of spring had arrived in 1925 when the disquieting news broke of further stability issues detailed by the State Architect. The decision on what to do with the building was not easily made, as so much had been spent, yet so much could be lost. New York State’s construction of the Lincoln and Washington Baths, just outside of town on South Broadway, and the success of those facilities aided the Commission’s decision to close the Phila Street bathhouse. After the bathhouse was razed in 1928, the property saw other uses. A grocery and liquor store operated on the site, and New York Telephone, which long had a presence on Putnam Street, expanded their space. In 1961 they erected the structure at 25 Phila Street, which is the Verizon building we see today. SS