14 minute read

Lost and Found

BY LAUREN REBECCA THACKER • ILLUSTRATIONS BY MARINA MUUN

Ceci n’est pas une pipe. Or, in English: this is not a pipe. René Magritte caused a stir when he painted those words below a highly realistic oil rendering of a pipe in his 1929 painting, La Trahison des Images (The Treachery of Images). The words were meant to provoke. They pointed out a rift between a representation of a thing and the thing itself.

But for speakers of multiple languages, the idea that an object and its verbal representation are distinct from one another is no provocation. To extend Magritte’s point: this is not a pipe, nor תרטקמ, nor ቧንቧ, nor نﻮﯿلﻏ. These words for pipe, in Hebrew, Amharic, and Arabic, respectively, are verbal and written representations of the same thing, but they are different sounds with different cultural connotations and traditions of use. And of course, in cultures without traditions of smoking, like Ancient Greece, there is simply no such word and no such thing. Multilingual speakers and writers hold these representations, connotations, traditions, and absences in their heads at once. Nili Gold says this ability is a double-edged sword.

“I think that for people who don’t know other languages, there is some sense of security. If a child only knows ‘table,’ they may think that the table was created as a table—that the word and the thing are the same,” Gold, Professor of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, comments. “When you have more than one language, you know that the signified is disconnected from the signifier. And that it’s all arbitrary. Meaning is arbitrary. But at the same time, knowing multiple languages gives you some sense of empathy, because you know that there are other ways of saying things and of looking at things.”

Because of the varied, culturally dependent ways of signifying meaning, people who want to translate a text from one language recognize that they cannot create an exact analog of the original. There can be a sense of loss in that recognition. Huda Fakhreddine, Associate Professor of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, puts it like this: “Translation places you face-to-face with the feeling that what you really set out to say is not going to be said. You really inhabit the loss, and you have to reconcile with that and channel it into making the translation more urgent.”

Emily Wilson, College for Women Class of 1963 Term Professor in the Humanities, expands on the power and danger of loss, joking that, “There can be a tendency for translators of ancient texts to fall into thinking like, ‘I feel so intense in the sense of loss. I feel that English is somehow inferior. So, I’m going to write a weird kind of English that will somehow make me feel better about the fact that this isn’t Greek.’”

Wilson’s 2017 translation of Homer’s Odyssey was celebrated for not being in weird English. The colloquial, modern version earned Wilson recognition as a 2019 MacArthur Fellow and a 2020 Guggenheim Fellow and has brought the ancient epic new attention.

Emily Wilson, College for Women Class of 1963 Term Professor in the Humanities

Geordie Wood

“I did a translation of Seneca’s tragedies in 2010, but nobody cared about that,” Wilson says with a laugh. She’s currently at work on a translation of Homer’s other epic, The Iliad.

“I don’t want my translations to be guided only by my sense of loss,” she says. “I want to acknowledge that I’m doing something different with the tools that I have. I want to celebrate the English language.” But the Odyssey had been translated into English many times before Wilson took it on. So why did she decide to spend five years translating 12,110 lines of Ancient Greek into English? Well, for starters, she was asked. An editor she’d worked with in the past expressed an interest in a new translation, and then Wilson had some thinking to do. “I don’t think we need endless retranslations,” she says. “So, I read over existing translations and then tried to meditate on what doesn’t get across. I asked myself, ‘Is there anything that I want to talk about when teaching the Odyssey that I have a hard time doing with the translations that are there?’ I decided that yes, there was something new to say.”

Wilson’s new approach resonated. When her translation was published in 2017, it was met with fanfare and acclaim from scholarly and popular publications alike, with The New York Times Magazine declaring in a feature, “The classicist Emily Wilson has given Homer’s epic a radically contemporary voice.” The Guardian called it a “cultural revelation” sure to “change how the poem is read in English.” Much ado was made about the fact that Wilson was the first woman to publish a complete English translation, but beyond that, critics celebrated her meter and structure: 12,110 lines of iambic pentameter for Homer’s 12,110 lines of dactylic hexameter. And then there are her spare, economical word choices, calling Odysseus “a complicated man” in the poem’s opener, while previous translations opted for descriptions like “the cunning hero” or “a man of twists and turns.” Later, she writes that “Athena, with her gray eyes glinting, gave / thoughtful Penelope a new idea,” while other translations are more fanciful, writing, “And now the Grey-eyed-One put into the heart / Of Penelope, Icarius’ wise daughter, / A notion.”

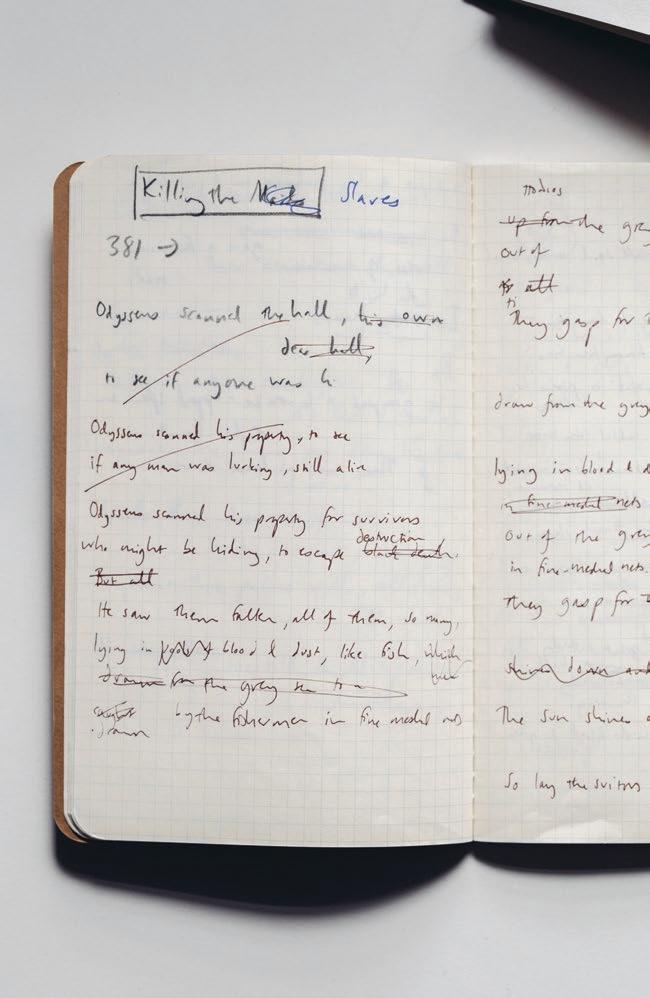

Wilson's notes on Homer’s Odyssey

Geordie Wood

Wilson’s translation moves quickly and embraces the shifts in tone and narrative point of view that make the poem complex and enjoyable. “It’s not just Odysseus’s story, but the stories of this whole rich tapestry of characters who live in a hierarchal social world,” she says. “I can show that, but at the same time, I think my translation is probably funnier than other best-selling ones.”

Dagmawi Woubshet, Ahuja Family Presidential Associate Professor of English, has a different set of considerations when he translates from Amharic to English, and vice versa. Woubshet, who emigrated from Ethiopia to the U.S. as a 13-year-old, isn’t comparing his work to previous translations, because there aren’t any.

Dagmawi Woubshet, Ahuja Family Presidential Associate Professor of English

Eric Sucar, University Communications

“For me, the act of translation is personal of course, but it’s also political and ethical given that it’s rare that we get African languages translated into a European lingua franca,” he says. “Our writers, talented as they are, have not assumed the world stage because they have not been translated into European languages.”

Woubshet’s current project, a translation of Sebhat Gebre Egziabher’s 1966 Amharic novel The Seventh Angel (ሰባተኛው መላክ), will introduce English readers to the work for the first time. The novel breaks away from its Ethiopian literary predecessors, Woubshet says, by using everyday Amharic and exploring queer sexuality, decolonization, and modernity. An English translation will bring attention to the book (once censored in Ethiopia), place the author in the context of international literary movements, and counter the false narratives about homosexuality as a Western import that Woubshet says are peddled by politicians and religious leaders. It also celebrates an author who made an impact on Woubshet’s own life.

Woubshet's notes on The Seventh Angel

“I first read the novel in 2009. It was a gift from a friend. Reading it, it totally arrested my attention,” Woubshet remembers. “As a queer Ethiopian, I felt corroborated by finding an Amharic text, an African writer who was broaching this issue as early as 1966. I knew then that my first book-length translation would be this novel.”

Fakhreddine felt a similar sense of inevitability when it came to her area of study, but translation added a new wrinkle. She grew up in Lebanon, where, she says, a history of colonization means that children are often educated in English or French, with little attention paid to Arabic traditions. It was different for her, because both her father, Jawdat Fakhreddine, and grandfather, Fakhreddine Fakhreddine, were poets writing in Arabic.

Fahkreddine has introduced her father’s poetry to the English-speaking world. With Jayson Iwen, she translated his collections Lighthouse for the Drowning (قيرغلل ةرانم) and, with Roger Allen, The Sky That Denied Me (ينتركنأ يتلا ءامسلا).

Huda Fakhreddine, Associate Professor of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations

Courtesy of Huda Fakhreddine

“Arabic poetry was never something I chose,” Fakhreddine says. “It was always my passion. But coming to this country for graduate school complicated things a little bit, because suddenly translation became a necessary medium. I took courses in translation studies and it pushed me to think about the politics of representation.”

“There’s this anxiety around representation when it comes to translations from Arabic,” she explains. “Compared to Greek, languages like Arabic and Amharic don’t have a long history of translation. So, there is a worry about a culture being contorted or distorted in its representation. This is something translators think about and contend with in our work.”

Readers of Arabic translations may be encountering the culture for the first time. In those cases, the translator is not only translating, Fakhreddine says, but inventing a literary tradition and creating a world for the audience.

Fakhreddine's notes on poetry

Courtesy of Huda Fakhreddine

That’s why she says, the more translations, the better. And if the English can retain an echo of the Arabic? Better still.

“When the English is disrupted, when it’s not as comfortable as it would be outside of the translation, that’s the ideal,” Fakhreddine says. “That’s very difficult to achieve. And we almost always fail at doing it. But the attempt is what makes the translation better.”

For Gold, disruption has been a career-long study. Born in Israel, she grew up speaking Hebrew to her parents, to neighbors, and at school. But Hebrew was not her parents’ first language, and they maintained a connection to the German of their youth through books and newspapers.

Nili Gold, Professor of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, at a reading for her book, Haifa: City of Steps.

Courtesy of the Jewish Studies Program

The related Modern Hebrew and Israeli traditions were shaped by writers for whom Hebrew was not a first language. In their hands, Hebrew, once the language of scripture and prayers, became the language of novels and poetry. In the 20th century, many prominent Israeli writers grew up speaking other languages and were separated, often violently, from the language and the life they lived in it. But their mother tongue—the language of their parents and childhood—never really left them.

In studying Hebrew and Israeli literature, Gold found power in analyzing the relationship between a writer’s mother tongue and his or her output in an acquired language. Aided by psychoanalytic theory, Gold shows the impact of the first language a writer spoke and heard—even, she says, in utero—on their eventual writing in another language, in this case, Hebrew.

The novelist Aharon Appelfeld is one such writer. In 2011, Gold organized a conference in his honor at Penn. Reflecting on his career and conversations with him, Gold says, “Applefeld was a Holocaust survivor. He only learned German until the age of eight, but he described parting from this mother tongue as having a limb cut off. He said he was always afraid that he would wake up in the morning having forgotten all the Hebrew that he learned with so much effort, because the language was not his.”

In her classes, Gold demonstrates the persistence of the mother tongue when she teaches Yehuda Amichai, a celebrated Israeli poet who left Germany at the age of twelve. “Amichai makes mistakes in Hebrew that come from his mother tongue,” she explains. “Or he uses syntactical structures that originate in German. And, when Amichai writes about the hard, wet, and cold earth of the spring, this is clearly European earth. It does not fit the Israeli climate. So, the echoes of German are not only linguistic features, but also represent a perception of the world.”

Translators must grapple with the fact the language is more than simply meaning. Woubshet, who is also working on a translation of his friend and former colleague Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon’s English poems into Amharic, says that, “With poetry, sound is just as essential as semantic meaning.”

Attention to sound and layers of meaning results in a process that can be more physical than other types of scholarly writing. “Both the hand and the mouth are very important for me,” Wilson says. “I read the original out loud to myself and then I try to create a draft. I usually write by hand first because then I can cross things out and rewrite it more easily.”

Woubshet completed his draft of The Seventh Angel in a series of notebooks before typing it up. “There’s a lot of erasing, there’s some blank spots for words that I have to look up in a dictionary,” he says. “Academic writing is a different kind of labor. I don’t want to minimize the hard work it took to translate this book. It was demanding, but it was also a leisurely activity for me.”

Translating Van Clief-Stefanon’s poems is proving to be more of a challenge, but a challenge that leads to moments of revelation. “This translation is an act of friendship and love for her poetry,” Woubshet says. “But translating from Amharic into English is easier for me because of my training as a literary scholar. In my head, I have a library of literary texts in the English language.”

He continues, “It was in translating her work with fidelity to sound that I found out new things about Amharic. She has this line that uses the word, ‘whisper.’ If you translate it in the gossipy way, in Amharic it is ሹክሹክታ, shukshukta. It’s an everyday word I have used countless times, but in that translation what I discovered was it was onomatopoeia. It had never dawned on me. In that moment, how you revel in that discovery!”

Later this year, Fakhreddine will publish a translation of the work of Salim Barakat, a Kurdish-Syrian poet whose work has never been translated into English. Like Woubshet, Fakhreddine has a library of English-language poets in her head, and she considers how they relate to Barakat and share in a larger poetic tradition. “I ask myself, who do I invite into my process, and can I create a community for him in English? It all goes back to the intimate process of reading both traditions and being sensitive about the power dynamic between them,” she explains.

Fakhreddine is currently part of a project that aims to retranslate 10 pre-Islamic poems called the Muʻallaqāt, or Hung Poems (تاﻘلﻌملا), so-named because they were supposedly hung on the walls of the Kaaba in Mecca. “I’ve been thinking about how best to create a space for them in English that’s different from the spaces created for them before,” she says. “When I read, I pencil in comments on the page. I like using a pencil. The book is usually marked-up as I read and translate. Then, there’s a very rough draft that’s all over the place on the page.”

On its journey from handwritten text to published book, a translation has many readers. Wilson values reading aloud to herself and to colleagues and students to get a feel for the poem’s meter. Fakhreddine often shares drafts back and forth with co-translators, and Woubshet asks colleagues and family to weigh in on rough drafts and word choice.

“Translation,” Fakhreddine says, “becomes a tradition of its own. It’s always important to approach a translation as one attempt among many.”

Gold agrees, saying, “Whenever more than one translation of a poem exists, I use it as a teaching moment. I point out the places where the translators had difficulties or where their translations differ the most from each other. And I tell my students, very often this is where the meaning of the poem lies—in those untranslatable spots.”

Because some things simply cannot be translated. Woubshet recalls Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s comment that translation is the language of languages. “Which is to say,” Woubshet explains, “this is how we commune across differences. Translation opens up an exchange and reveals and revels in the gaps. What is ineffable? Not everything has a one-to-one equivalent, right? What is ineffable is, I think, just as rich and profound.”