Ironwood

MAGAZINE OF SANTA BARBARA BOTANIC GARDEN

ISSUE 32

Editor-in-Chief: Jaime Eschette

Editor: Brie Spicer

Designer: Kathleen Kennedy

Staff Contributors: Hannah Barton; Michelle Cyr; Matt Guilliams, Ph.D.; Denise Knapp, Ph.D.; Zachary Kucinski; Jenny McClure; Rikke Reese Næsborg, Ph.D.; Keith Nevison, Ph.D.; Zach Phillips, Ph.D.; Scot Pipkin; Katherine Sanders; Danielle Ward

Guest Contributors: Sam Babcock, Mary Brown, Julia McHugh, David Starkey

Ironwood is published biannually by Santa Barbara Botanic Garden.

As the first botanic garden in the nation to focus exclusively on native plants, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden has dedicated nearly a century of work to better understand the relationship between plants and people. Growing from 13 acres in 1926 to today’s 78 acres, the grounds now include more than 5 miles of walking trails, an herbarium, a seed bank, research labs, a library, and a public native plant nursery. Amid the serene beauty of the Garden, teams of scientists, educators, and horticulturists remain committed to the original spirit of the organization’s founders — to conserve native plants and habitats to ensure they continue to support life on the planet and can be enjoyed for generations to come. Visit SBBotanicGarden.org.

The Garden is a member of the American Public Gardens Association, the American Alliance of Museums, the California Association of Museums, and the American Horticultural Society.

©2022 Santa Barbara Botanic Garden. All Rights Reserved.

Santa Barbara Botanic Garden 1212 Mission Canyon Road Santa Barbara, CA 93105

Garden Hours

Daily: 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Members’ Hour: 9 to 10 a.m.

Phone: 805.682.4726

Garden Nursery: ext. 112 Development: ext. 103

Education and Engagement: ext. 161 Membership: ext. 110 Registrar: ext. 102 Volunteers: ext. 119

Board of Trustees

Jeremy Bassan

Sarah Berkus Gower

Sharon Bradford

Frank W Davis, Ph.D.

Samantha Davis, Ph.D. Mark Funk, Treasurer

John Gabbert, Vice Chair

Valerie Hoffman, Chair

Leadership Team

George

Jaime Eschette, Director of Marketing and Communications

Jill Freeland, Director of Human Resources

Denise Knapp, Ph.D., Director of Conservation and Research

Keith Nevison, Director of Horticulture and Operations

Melissa G. Patrino, Director of Development

Scot Pipkin, Director of Education

Steve Windhager, Ph.D., Executive Director

Join Our Garden Community Online

Sign up for our monthly Garden Gazette e-newsletter at SBBotanicGarden.org and follow us on social media for the latest announcements and news.

Ironwood Volume

32 | Fall/Winter | 2022-23

Leis Bibi Moezzi

Contents 1 Welcome Message 3 Adventures in Lichenology 8 80,000+ Herbarium Specimens Digitized, Now on Public Data Portal 10 The Garden’s Impact 12 Plant with Purpose: Attract and Delight Feathered Friends 19 The Long Kiss Goodnight: Following an Invasive Ant-mimicking Spider from Texas to California 23 Pruning Natives Demystified 26 Inside the Garden Nursery: Staff Tips for Fall 30 From the Archives: Designating California’s State Tree(s) 32 Member Story: Moving at the Speed of Nature 36 Field Notes: Poetry Inspired by Nature 37 The Book Nook: Our Latest Book Recommendations 40 Budding Botanist: Activities To Support Our Local Birds Santa Barbara Botanic Garden @SBBotanicGarden

Barbara Botanic Garden

the cover: St. Catherine’s lace buckwheat (Eriogonum giganteum)

William Murdoch, Ph.D. Helene Schneider Warren Schultheis Kathy Scroggs, Secretary Ann Steinmetz

Santa

On

(Photo: Denise Knapp, Ph.D.)

While our Executive Director Steve Windhager steps away for his much-deserved three-month sabbatical, it is my pleasure to open this fall/winter issue of Ironwood.

In the 10 years that I’ve worked with Steve as Santa Barbara Botanic Garden’s director of conservation and research, I’ve seen so many exciting changes. The Garden’s Living Collection looks better than ever, we have record-breaking levels of membership, and our visitation numbers continue to reach our county-issued capacity limits.

It’s a joy to host each of our guests — especially the many families exploring and enjoying our newest immersive section of the Garden, the Backcountry.

As we begin the countdown to our centennial in 2026, we are more committed than ever to pursue our mission to conserve California’s native plants and habitats. After all, native plants are the base of global biological diversity and are key to sustaining life on Earth. To that end, our Conservation and Research Department has been growing and thriving as well. With the opening of the Pritzlaff Conservation Center in 2016, we gained critical space for our labs, collections, and offices. This allowed us to expand our work and tackle the myriad of conservation challenges — from the (sub)microscopic level of genes to the landscape level of ecosystems. We now have 22 scientists on staff, passionately covering a range of disciplines from botany to lichenology, rare plant biology to genetics, and ecological restoration to insect ecology.

When describing our conservation work, I think of it like building a three-layer cake. The base layer, supporting the rest, is biodiversity knowledge. We must know the species we are working with, where and how frequently they are found, what communities they form, and how they interrelate to other species. Then, for the middle layer, we need to balance and protect those living “ingredients.” We must do what it takes to save rare species, because everything has a job to do and losing biological diversity will make the cake crumble. And for the top of our cake, with all the support of the bottom layers, we must work to restore functioning native habitats that support life — from the plants and lichens to the bugs and the birds. The icing is you, our supporters, who make all of this important work possible.

In this issue, you’ll read about some of this critical “cake making,” including our lichenologist’s work to inventory lichens, protect rare ones, and educate about them; our botanists’ work to use our herbarium specimens to better understand climate change; and how native plants have a crucial role in attracting wildlife, specifically birds, right in your backyard.

I hope these stories inspire you to join us in our important conservation efforts. Start small with one native plant or expand to a full garden (late fall and early winter is the best time!). Help to document species through apps like iNaturalist. Or join us as a volunteer in the Garden — there are numerous opportunities. Whatever path you choose, it makes an impact, and we’re so grateful for your support. Together, our green thumbs can make a difference.

See you in the Garden, Denise Knapp, Ph.D. Director of Conservation and Research

Welcome

Ironwood 1

Message

2 Ironwood

Adventures in Lichenology

By: Julia McHugh

Rikke Reese Næsborg, Ph.D., has scaled a coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) in Big Basin Redwoods State Park and is now secured by ropes in the crown of the swaying, nearly 300-foottall (91-meters-tall) tree. After peering through a magnifying hand lens to examine tiny, complex organisms encrusting the tree’s bark, she makes a few notes before securing a small sample and carefully repelling back to the forest floor.

Rikke is Santa Barbara Botanic Garden’s lichenologist, one of only two paid, full-time lichenologists in California. She travels throughout California to perform inventories, collect specimens, and conduct studies of this unique, often misunderstood life form. Many people think lichens are a type of moss, but they are not. They are neither plants nor animals, and not even a single organism. Lichens are unique organisms in which algae (or cyanobacteria) live among fungi in a mutually beneficial, or symbiotic, relationship. The fungi provide a structure and protection from the environment for the algae, while the algae use photosynthesis to produce food for themselves and the fungi. Lichens take no nutrients from the growing surface itself — instead they receive moisture and other nutrients from air. They can grow on nearly any undisturbed surface: bark, wood, rock, soil, glass, metal, plastic, and even cloth.

That means lichens can grow almost anywhere on Earth — and they do. Incredibly diverse, there are more than 5,300 species of lichens in North America alone, and new species are discovered regularly. Rikke has described six new species, which involves giving them scientific names, and she has one more to describe.

Lichens can range in color from bright yellow, red, and orange to green, black, brown, silver, and gray, and they may change color when wet. Colors are usually a result of the lichen chemistry which may contain pigments. The chemical compounds have different functions such as protecting the lichen against excess sunlight or preventing herbivory (discouraging animals from feeding on them). Side products of these pigments are the vibrant colors. “Lichens are very complex little ecosystems in themselves,” says Rikke. “They even have been taken into space and

exposed to ultraviolet radiation and were still able to reproduce and photosynthesize when they returned to Earth.”

Recently, Rikke spent several days on San Nicolas Island, 61 miles (98 kilometers) off the California coastline. Managed by the U.S. Navy, it is usually off-limits to civilians, but she’s there to conduct a lichen inventory, which is expected to be completed by June 2023.

Opposite: Macrolichens, more specifically gray lace lichen (Ramalina menziesii) and orange golden-eye lichen (Teloschistes chrysothalmus) are growing on an oak branch near Grass Mountain, Santa Barbara County. (Photo: Rikke Reese Næsborg, Ph.D.)

Ironwood 3

A tiny sliver of really hard rock on an otherwise highly erosive island offers a stable surface for lichens. Here, Tucker Lichenologist Rikke Reese Næsborg, Ph.D., hopes to discover species that are new additions to the San Nicolas Island’s biodiversity checklist. (Photo: Cameron Williams)

Even more travel is required for another of her projects: a guidebook to macrolichens in California.

The “macro” in macrolichen not only refers to size but also to the growth form. These lichens appear bushlike or leafy, and their physical features are visible to the naked eye. All other lichens are called microlichens which look two-dimensional and often require a microscope for identification (See: A Magnified Look at Microlichens). “The research for the guide is taking place at the speed of lichenology, which means very, very slowly,” says Rikke. “The previous guide only included 300 of California’s lichen species, but there are 600 to 700 species of macrolichens in the state.”

Rikke also helps evaluate the extinction risk of California lichens for the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List and works with the California Lichen Society and California Native

Plant Society to evaluate possible endangered lichen species.

She earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees at University of Southern Denmark and earned a doctorate in systematic botany from Uppsala University in Sweden. A California resident since 2011, she joined the Garden staff in February 2019 as the Tucker lichenologist and curator of the Garden’s Lichenarium.

The Lichenarium currently holds around 35,500 lichen specimens, but that’s about to change. The Garden is absorbing the entire lichen collection of more than 16,000 specimens from the Herbarium of the University of California, Riverside (UCR). The Garden also is the official repository for specimens from the Channel Islands National Park, which is one reason why the UCR Herbarium collection came here.

4 Ironwood

Four to five different species of microlichens are growing on a rock near Grass Mountain in Santa Barbara County. Notice the rusty-green moss to the left for scale. (Photo: Rikke Reese Næsborg, Ph.D.)

With the help of Lichenarium Technician Danielle Ward, Rikke is integrating the two collections, which will take at least a year. It means they handle every single specimen to add bar codes, update genus and species names, and confirm that specimen information is correct in the online database managed by the Consortium of North American Lichen Herbaria (LichenPortal.org).

Back in the redwoods, Rikke is involved in two studies. The first, in the southernmost part of the redwood range, explores environmental drivers behind the organization of lichen communities on the trees. We are finding that the redwoods are hosts to many more lichens than previously thought. These trees are incredibly species rich. We found over 100 species in one tree alone, and a lot of diversity even in new species.

The second study, in northern California, examines the lichens that grow on other plants that also grow on the coast redwoods. That’s three layers — for example, a lichen on a huckleberry shrub (Vaccinium ovatum) on a redwood tree. “Epiphytes are plants that grow on other plants — ‘epi’ means ‘on top of’ and ‘phyte’ is ‘plant,’” says Rikke. “Lichens are also epiphytes, and this study focuses on the lichens growing on other epiphytes, namely huckleberry (Vaccinium ovatum and V. parvifolium) and western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), growing on redwoods.”

The goal of the second study is to identify any differences in the lichen communities on branches of redwood versus branches of epiphytic shrubs and trees. “We expect not just a difference but that the epiphytic shrubs and trees will host a more diverse lichen community, which amplifies the biodiversity contained within old-growth redwood forests,"

Ironwood 5

Rikke notes. Lichens face pressure from smog and other forms of air pollution, and their habitats are threatened by real estate development and fire. Rare or endangered lichens could be completely wiped out by fires in regions where they grow. Since it can take more than 50 years for a lichen population to recover, Rikke’s work is critical given the reality of a warming planet.

“Lichens are a big part of the planet’s ecosystem,” says Rikke. “They are the first to arrive after a glacier melts and contribute to soil-making by slowly breaking down rocks. Up to 50% of nitrogen and many other nutrients in a forest come from lichens. Reindeer depend on them for up to 90% of their winter diet, and they provide food and shelter for other animals. Not to mention, I’ve always enjoyed seeing when hummingbirds use lichens to decorate their nests.”

It’s been 17 years since Rikke climbed her first tree, a giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum) in the Sierra Nevada. She recalls being terrified as she peered both above and below on her accent. However, she pushed on, all the way to the top. “In many ways, science in general and my research in particular is like

my initial climb,” she says. “It can be challenging and a bit overwhelming, but it has the potential to lead to a greater understanding of our environment and it will hopefully increase protection of the natural world.” O

This hummingbird nest is decorated with pieces of ruffle lichen (Parmotrema sp.) and common greenshield lichen (Flavoparmelia caperata). Two hatchlings are cozying up in the nest. (Photo: Rikke Reese Næsborg, Ph.D.)

This hummingbird nest is decorated with pieces of ruffle lichen (Parmotrema sp.) and common greenshield lichen (Flavoparmelia caperata). Two hatchlings are cozying up in the nest. (Photo: Rikke Reese Næsborg, Ph.D.)

6 Ironwood

Happily foraging for lichen diversity 200 feet (60 meters) above the ground, Rikke Reese Næsborg, Ph.D., collects data in a coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens). (Photo: Wendy Baxter)

A Magnified Look at Microlichens

Like mushrooms, lichens produce spores in specialized structures. In this close-up cross section of the spore-producing structure of the microlichen aromatic toniniopsis (Toniniopsis aromatica), the green near the top is the structure’s exterior, and the red-brown layer near the bottom is the foundation, which supports sacks where the fungal spores are produced.

Look carefully in the white bottom-left corner — can you spot one of the sausage-shaped spores? It is 0.0006 of an inch (.015 millimeters) long, which is four to five times smaller than a human hair is wide. This kind of tiny detail is often the only way researchers are able to identify a species of microlichen.

Ironwood 7

80,000+ Herbarium Specimens Digitized, Now on Public Data Portal

By: Matt Guilliams, Ph.D., Tucker Systematist and Curator of the Clifton Smith Herbarium

Located on the east side of Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, across from its main entrance, the Pritzlaff Conservation Center serves as the central hub for the Garden’s conservation work. The basement of this fire-safe building is home to the Clifton Smith Herbarium, the Garden’s collection of dried plant specimens. This American Alliance of Museums (AAM) accredited collection is the result of decades of collection and recording work and is used by our team of scientists to better understand our natural world — and it is soon to be even more widely available.

Combined with the co-housed Lichenarium and Fungarium, there are a total of approximately 210,000 specimens in the Garden’s collection. This makes it the largest collection of preserved plant, lichen, and fungus specimens from California’s hyper-diverse central coast and Channel Islands.

Recently, we completed a four-year project to digitize over half of the Herbarium’s collection — more than 80,000 of approximately 155,000 plant specimens.

The Garden is among 22 California partner institutions who participated in the National Science Foundation–funded project “Capturing California’s Flowers: using digital images to investigate phenological [the timing of biological events] change in a biodiversity hotspot.”

The project was conducted under a novel data standard that was specifically developed for this project but deployable to similar efforts worldwide.

The digitized specimen data and images are now housed on a new, publicly accessible data portal (CCH2.org) for use by biodiversity and conservation scientists around the globe.

For the Garden’s part of this grant, we obtained highresolution digital images of a total 81,497 specimens, which took the better part of four years to complete. The grand total from all 22 participating institutions is more than 904,200 specimens.

In addition to the benefits to science and conservation, this project involved hundreds of students and other volunteers who received training and developed expertise in natural history collections. Some have turned this experience into employment in the field, including at the Garden. This is especially gratifying as 58% of project participants were women, and more than 16% were from groups that are traditionally underrepresented in STEM.

The project partners generated a massive dataset capable of addressing critical questions about the flora of California, a biodiversity hot spot that is experiencing rapid climate shifts. These data and images are critical resources for biodiversity scientists in their study of the world we live in.

Additional information about this project, such as protocols, educational resources, and our blog, can be found at CapturingCaliforniasFlowers.org. O

Opposite: This is a high-resolution image of Sonoran maiden fern (Pelazoneuron puberulum var. sonorensis; Theypteridaceae), a beautiful but seldom-seen inhabitant of creeks and streams in the Santa Ynez Mountains. This species reaches the northwestern edge of its range in Santa Barbara County.

Garden herbarium technicians Susana Delgadillo and Eli Balderas are hard at work creating high-resolution images of specimens for the National Science Foundation digitization project.

8 Ironwood

Ironwood 9

Together, Our Green Thumbs Make a Difference

With your generous support, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden is inspiring and empowering everyone to cultivate biodiversity — both locally and beyond — so we can restore the health of the planet, one seed at a time.

Here’s what we’ve accomplished in 2022 so far.

1,246

People experienced the power of native plants and habitats through our educational programming.

4,000+

Thousands, age 2 to 12, visited in the first 100 days of our new Backcountry Section opening. Thanks for making us a runner-up for the Best Family Fun Spot.

Nature-inspired Playhouses

Casitas were installed with the help of community partners.

3,500 Hours

Children explored, learned about, and experienced native plants in our 5-week Summer Camp program.

New Species & Cultivars

The Garden’s Living Collection keeps growing.

Distinct plants were added to the Garden this year, including 40 rare and threatened plants and 15 new trees.

Irrigation Units

Carts and power tools transitioned to electric, reducing the Garden’s carbon emissions.

THE GARDEN’S IMPACT

5

Over 75% Converted

12

1,200

7

We expanded our centralized system, increasing our ability to monitor and control water usage and waste. 10 Ironwood

16,000

581

344 Volunteers

You helped drive our mission forward.

Volunteer hours clocked — and the year isn’t over yet!

Native plants and 2,230 seeds sold at the Garden Nursery so far this year. 210,000

Specimens

The Clifton Smith Herbarium continues to grow, with 81,497 specimens recently digitized. (See story on page 8.)

These have been described by the Garden’s lichenologist, who is 1 of only 2 paid, full-time lichenologists in California. (Read our lichenologist’s story on page 3.)

Guests accessed the Garden through the Museums for All program, which supports lowincome families.

110,000

Total Visitors

So many have enjoyed the Garden this year, with 1 in 5 from outside California. Your reviews made us a 2022 Tripadvisor Travelers’ Choice recipient.

548,082 Seeds Produced

Seeds from the Channel Islands were collected and germinated at the Garden, which produced many more seeds for on-island recovery projects by our Rare Plant Team.

6New Lichen Species 54,890

Invertebrates were identified and imaged following a survey on San Clemente Island, as we aim to better understand, protect, and restore biodiversity on the island.

5,278 Garden Members

our

Thank you for supporting

mission! 8,600

Ironwood 11

Plant with Purpose: Attract and Delight Feathered Friends

By: Scot Pipkin, Director of Education

Beauty. Respite. Sense of place. For many, gardens offer emotional nourishment and peace of mind. For some of us, this relationship approaches a spiritual level of significance. Partly, this is the result of a deep human urge to engage with our surroundings and cultivate the earth. There is something hopeful and celebratory associated with planning and planting a garden. What could be more fulfilling than facilitating life and watching it flourish? At the same time, gardening, particularly gardening with native plants, offers the promise to beget even more life in the form of other organisms that visit our yards for the flowers, food, and shelter we’ve cultivated.

To some degree, the delight we get from seeing a butterfly, bumblebee, or bird in our garden is due to the seemingly random distribution of these animals. One week they’re there, the next week they’re gone. They are independent beings, after all, with brains, life histories, and agendas of their own. However, with some thoughtful planning and appropriate selection of plant material and landscape features, we can greatly increase the chances of attracting a diverse array of organisms to our gardens and neighborhoods.

Beyond the personal joy and fulfillment that comes from seeing a migrating bird, butterfly, or dragonfly (yes, there are migratory dragonflies!) in one’s yard, it’s becoming increasingly critical to use our backyards and neighborhoods to support wildlife. Habitats continue to be fragmented into smaller parcels by urban development, the use of chemical pesticides disrupts ecological processes, and climate change looms — so our neighborhoods and backyards make gardening, particularly with native plants, an action that shifts from personal gratification to environmental activism. Even in the smallest yard, we can support the smallest organisms. In turn, those organisms provide food and other benefits for the rest of our ecological network.

Gardening Is for the Birds

In many ways, birds are the perfect target for wildlife gardening. Though sometimes furtive and skulk-y, birds tend to be visible, active, and gregarious in the garden. They also live on every continent, provide numerous ecological benefits, and exhibit some of the most incredible life histories. (Did you know that the rufous hummingbird, which migrates up the

Pacific coast in spring and down along the Rocky Mountains after breeding in late summer/fall, has the longest migration relative to body length of any bird?) Moreover, birds tend to be higher up in the food chain than many other animals we should reasonably expect to attract to our yards. This means if we’re doing a good job of attracting birds to our yards and neighborhoods, we’re also benefitting countless other critters.

In addition to the sheer abundance of birds, they are diverse and beautiful. A garden full of birds is a riot of color and of sound. Birdsong is nature’s poetry and has filled people’s dreams throughout the millennia. If those songs have their desired effect, they yield one of the most foreign, yet familiar processes in the animal kingdom: nesting, egg laying, hatching, and fledging. We as humans can identify with the great care that many birds take to build nests and then feed their young, protect them, and watch them fledge. At the same time, we watch with a mystical fascination, bewildered by the seemingly miraculous appearance of bird from egg.

Beyond this, birds are beneficial. Many of them eat insects throughout the year. Almost all songbirds feed their young a diet that consists exclusively of insects. Often, that diet is dominated by the scourge of many gardeners: caterpillars. Therefore, if we’re attracting birds, we get to benefit from watching the joy and drama of avian life as well as natural pest control. The key to attracting the highest diversity of native insects to one’s yard is to use native plants. Many insects, especially caterpillars, have evolved to eat very specific foods during critical stages in their lives. Without those host food plants, the insects will not be there. No insects means fewer birds, especially during spring/fall migration and the breeding season of May to August. For those of you keeping score, that’s about eight months of the year.

Tips for Successfully Attracting Birds

1.

Setting Expectations

It’s always important to build an understanding of what birds you can reasonably attract to your yard. Though it is entirely within the realm of possibility that your backyard could become a haven for rare and migrating birds, it’s more likely that a welldesigned garden is going to attract more of the common birds in an area. If you don’t know what

12 Ironwood

Ironwood 13

California Thrasher (Photo: Denise Dewire)

birds are in your area, there are a few ways to learn more. First, you can go outside and start watching birds. You can also use tools such as eBird.org to explore bird sightings people have submitted in your area. There are great visualization tools to see what birds you can expect at what times and relatively how abundant they are for a given location. Once you are armed with a greater understanding of your local bird life, you can do a better job of providing the resources that those birds need to thrive.

One must also consider the expectations of the birds. Once we begin providing great structure and forage for these organisms, they will come to expect resources that we provide. To continually support the birds once an attractive habitat has been installed, it’s important to maintain that habitat. Make sure features, such as water sources, nest boxes, and other accoutrements, are kept clean and accessible. Plants should be well cared for so they continue to provide the food and structure birds need.

2. Habitat Structure As with any organism, birds require certain habitat conditions to be successful. Each bird has a preferred setting for feeding, nesting, and hiding. In general, it is a good idea to consider the different planes of habitat you might be providing. For instance, what does your ground plane look like for birds that eat seeds? Does your garden have spaces where birds, such as the Dark-eyed Junco or Spotted Towhee, can nest on the ground under the cover of a shrub? Similarly, it’s helpful to consider what your mid-canopy and canopy layers provide in terms of places to forage, nest, and roost. Small- to medium-sized shrubs can be great choices to install for creating a variety of layers in your habitat. In addition to providing birds with the feeding/perching structures they need, well-designed layers can help your garden look more appealing.

One important principle that must be considered when creating bird habitat is where the birds will hide. If you’ve ever paid attention to bird behavior while walking in nature, you’ve probably noticed that there is a tendency to scatter when you or another animal (such as a dog or cat) approaches. I challenge you to keep watching and see exactly where the birds go once startled. Oftentimes,

you will find that they fly straight for the darkest shadow they can find. If you try to layer your habitat both vertically and with depth, birds will be grateful for the hiding spaces you provide and will show their gratitude by appearing in your yard.

3. Provide the Right Food Through Native Plants

Given their diversity, birds have a wide range of foods that sustain them. Insects have already been introduced as an important food source, but there’s more to that story. Caterpillars are one of the most important food sources for birds during breeding season and beyond. Certain groups of plants are particularly good at attracting a wide variety of caterpillars. Chief among those are oaks (Quercus spp.), wild cherry (Prunus ilicifolia and P. ilicifolia lyonii), and buckwheats (Eriogonum spp.).

Other important food sources include seeds, nectar, and fruit. Some plants that provide those are members of the sunflower family (Asteraceae), those with tubular red flowers (i.e., hummingbird sage [Salvia spathacea] and California fuschia [Epilobium canum]), and coffeeberry (Frangula californica), respectively.

Providing food throughout the course of the year is another essential consideration. Many of the birds we can hope to attract to our yards are yearround, or resident birds, so ensuring resources throughout the seasons is critical for maintaining those populations. At the same time, there is an array of birds that are highly seasonal, spending either the breeding, wintering, or migration periods in our neighborhoods. Ensuring an abundance of food and resources during those critical life stages is important as well.

A corollary to planning one’s garden to support birds and other wildlife is that the traditional maintenance regime should be reconsidered. Whereas traditional ornamental gardening practices would prescribe quickly removing the seedheads of pollinated flowers (deadheading), wildlife gardeners are recommended to leave the seedheads of their Encelia, Eriogonum, and other flowers.

Overall, it’s important to understand the birds and what they need.

14 Ironwood

Anna’s Hummingbird

Appearance: Medium-sized hummingbird around 4 inches (10 centimeters); when perched, wings extend almost to the tip of the tail; males display a vibrant magenta gorget and head feathers.

Behavior: Often hovers while hunting insects; during courtship, males will perform a “display flight” where he dive-bombs in an exaggerated J shape in front of the female.

How Native Plants Support Them: A hummingbird’s diet is composed of two primary foods: nectar and insects. Red, tubular flowers are particularly attractive to hummingbirds and a combo of hummingbird sage (Salvia spathacea), climbing penstemon (Keckiella cordifolia), and California fuschia (Epilobium canum) could potentially cover an entire year’s worth of attractive blooms. Dense shrubs offer attractive nesting habitat for Anna’s Hummingbirds.

California Towhee

Appearance: 9 inches (22 centimeters); long-tailed sparrow-like bird that spends most of its time on the ground; gray-brown overall with a rufous patch under the tail.

Behavior: Generally more secretive and unassuming than the Spotted Towhee. California Towhees spend most of their time feeding on the ground; these birds build their nests below about 6 inches (15 centimeters) in shrubs and small trees with dense foliage.

How Native Plants Support Them: California Towhees rely primarily on plants for food. Therefore, providing plants with nutritious seeds, such as California daisy (Encelia californica), or fruits, such as redberry (Rhamnus crocea), are good choices.

the Birds: Collect All Six in Your Backyard

Meet

Anna's Hummingbird (Photo: Alan Schmierer)

Hummingbird sage (Salvia spathacea) (Photo: Lynn Watson)

California Towhee (Photo: Alan Schmierer)

Ironwood 15

California Daisy (Encelia californica)

Hooded Oriole

Appearance: A medium-large songbird at about 7.5 inches (19 centimeters); males are particularly colorful, displaying bright yellow-orange head, back, and underparts contrasting with a black “bib” on its throat. Females and juveniles show a yellow wash over head, back, and breast. Both males and females have white wing bars against dark wing feathers. Male wings are darker black, and females have gray wing feathers.

Behavior: Hooded Orioles spend much of their time in the canopy of trees, calling and singing from high perches. Being omnivores, they feed on a variety of foods ranging from insects to nectar (they will come to hummingbird feeders) and fruit. One of the most remarkable aspects of orioles in general is their nest, which is an intricately woven hanging cup.

How Native Plants Support Them: Hooded Orioles eat nectar, fruit, and insects, such as caterpillars, that rely on native plants. They also utilize native plants extensively during the breeding season for nesting purposes. In particular, the California fan palm (Washingtonia filifera) provides an important source of nest weaving materials and dead fronds that hang against the trunk provide perfect nesting locations for these birds.

Lesser Goldfinch

Appearance: Small at 4.5 inches (11 centimeters), songbird; bright yellow belly contrasting with blackand-white wings; males have a dark cap on their head and a greenish-yellow back; females are greenishyellow all over head and back.

Behavior: Typically seen in small flocks, these birds are vocal and acrobatic feeders. Often, they can be seen perched on a flower stalk that is swaying with their weight.

How Native Plants Support Them: Lesser Goldfinches are quintessential seed eaters, with a smattering of fruits and young leaves mixed in. Sages (Salvia spp.) provide an excellent food source, as do coyotebrush (Baccharis pilularis) and deergrass (Muhlenbergia rigens).

Hooded Oriole (Photo: Alan Schmierer)

Lesser Goldfinch (Photo: Alan Schmierer)

California fan palm (Washingtonia filifera)

Allen Chickering Sage (Salvia spp.)

Purple sage (Salvia leucophylla) (Photo: Ron_Williams)

Hooded Oriole (Photo: Alan Schmierer)

Lesser Goldfinch (Photo: Alan Schmierer)

California fan palm (Washingtonia filifera)

Allen Chickering Sage (Salvia spp.)

Purple sage (Salvia leucophylla) (Photo: Ron_Williams)

16 Ironwood

Deergrass (Muhlenbergia rigens) (Photo: Elizabeth Collins)

Spotted Towhee

Appearance: 8.5 inches (21 centimeters); long-tailed, deep-bellied bird; mostly black upper with spotted wings; dark “hood” with a contrasting red eye; rufous flanks and light underside.

Behavior: Distinctive “double hop” as it moves leaf litter in search of insects, seeds, and fruit. Creates a nest on the ground, under the cover of shrubs.

How Native Plants Support Them: Native plants provide a layer of leaf litter that attracts the insects Spotted Towhees need to eat, particularly in the breeding season. Specific plants, such as toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia), elderberry (Sambucus nigra caerulea), Catalina cherry (Prunus ilicifolia lyonii), and coffeeberry (Frangula californica) provide fruit/seeds that towhees love.

White-crowned Sparrow

Appearance: Large sparrow with bold white-andblack stripes on its crown; gray breast fades to brown wings with white wing bars; long-tailed; juveniles have rufous on the crown and a red eye stripe.

Behavior: Spends most of its time on the ground, where it feeds primarily on seeds. White-crowned Sparrows tend to exhibit flocking behavior, so if you attract one, you’ll probably have many in your yard. As spring approaches, they increase their intake of insects for food.

How Native Plants Support Them: Being primarily an herbivore, plants are critical for providing Whitecrowned Sparrows with food. In the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, these sparrows are commonly seen in the Ground Cover display in winter, where they are feeding on the seeds of sages, buckwheats, and coyote brush (Baccharis pilularis). O

Buckwheat (Eriogonum arborescens) (Photo: Sangeet Khalsa)

Spotted Towhee (Photo: Alan Schmierer)

White Crowned Sparrow (Photo: Alan Schmierer)

Buckwheat (Eriogonum arborescens) (Photo: Sangeet Khalsa)

Spotted Towhee (Photo: Alan Schmierer)

White Crowned Sparrow (Photo: Alan Schmierer)

Ironwood 17

Toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia) (Photo: Randy Wright)

18 Ironwood

The Long Kiss Goodnight: Following an Invasive Ant-mimicking Spider from Texas to California

By: Zach Phillips, Ph.D., Terrestrial Invertebrate Conservation Ecologist

By: Zach Phillips, Ph.D., Terrestrial Invertebrate Conservation Ecologist

In the past few decades, the spider Falconina gracilis has become established in California (Valle et al. 2013). Although Falconina is a widespread invasive predator, we don’t know much about its biology or ecological impact. What little we do know includes the following: it comes from South America, mimics and eats ants, and seems to have adapted well to human environments (Fowler 1981; Valle et al. 2013). In other words, the spider is a bit of a hanger-on in two different kinds of societies: those of ants and people (Photo 1).

Kiss of Death

During the first pandemic lockdown, I brought my research home with me (i.e., I covered the apartment with spiders). I had time — too much time — to study Falconina’s predation in detail, and I discovered that Falconina eats ants in an exceptional way. Typically, the spider follows an ant from behind, bites the ant’s posterior, and then retreats until its venom takes effect. So far, nothing special. What happens next is the strange part. Falconina maneuvers the incapacitated ant into a mouth-to-mouth position and feeds on the contents of the ant’s head.

Falconina and I share this in common – I’m also a bit of a parasite on ants (and on people, if you want to be mean about it). During graduate school in Austin, Texas, I studied Texas leaf-cutter ants (Atta texana), collecting them for research, shamelessly observing their private lives, and being a general pest. This led to my first encounter with Falconina on a leafcutter nest mound (Photo 2), where the spider was pretending to be just one of the ants.

In stillness, Falconina doesn’t look much like an ant. In motion, however, it is a consummate artiste. The spider moves its front legs like antennae (ants have antennae, spiders don’t) and lifts and “bobbles” its abdomen like many ants do, and it can adopt the general saunter of an ant. I was bewitched, and over the next few years I discovered a few things about Falconina’s basic biology (Phillips 2021), including details of how it eats (Kiss of Death) and what it eats (Queen Killer), findings that can inform predictions of Falconina’s impact here in California (Falconina in California).

3, 4, 5: The spider’s kiss of death: Falconina gracilis maneuvers a Texas leaf-cutter ant (Atta texana) forager into a mouth-to-mouth position and proceeds to eat the contents of its head. (Photos: Alex Wild)

Opposite, 2: The author annoys a Texas leaf-cutter ant (Atta texana) colony at Brackenridge Field Laboratory in Austin, Texas. (Photo: Larry Gilbert, Ph.D.)

1: A Falconina gracilis spider literally hangs on to an ant between its jaws. (Photo: Alex Wild)

1: A Falconina gracilis spider literally hangs on to an ant between its jaws. (Photo: Alex Wild)

Ironwood 19

Ant heads are full of high-value nutrients but well protected by a thick cuticle. As a consequence, they can be difficult for predators to breach. The mouth, however, is a weak spot. Falconina may have evolved its “kiss of death” as a way to gain easy entry to ant heads and the riches within.

Queen Killer

When a predator eats a few ant foragers, it doesn't do much harm to the colony that they belong to; the effect on the colony is like the effect a mosquito bite has on you or me. On the other hand, if a predator kills the colony’s queen, it destroys the colony.

My fieldwork in Texas suggests Falconina is a queen killer. Not a killer of just any queens, but of new queens starting new colonies with no nestmates to protect them. At my research sites, I found Falconina occupying the new nests of carpenter ant (Camponotus sansabeanus) queens. Occasionally, I would find a queen’s carcass, still intact but dried out,

just outside her nest entrance. Other times I found the decapitated heads of queens, along with other insect body parts, attached to nearby Falconina egg sacs (this gory egg sac ornamentation may be a form of Falconina maternal care, deterring potential egg sac predators and parasitoids) (Photo 6). Furthermore, in feeding trials conducted in the lab (i.e., my apartment), Falconina quickly incapacitated and ate carpenter ant queens (Photo 7). Collectively, these findings indicate Falconina can acquire big meals and valuable shelters from new queens; however, it’s unclear if the spiders specifically target new queens or attack them opportunistically.

Falconina in California

Falconina remains relatively unknown and understudied in California. For instance, we don’t really know what Falconina eats here, essential information for predicting an invasive predator’s ecological impact.

6: Insect body parts, including the head of a carpenter ant (top left), covering a Falconina egg sac. (Photo: Zach Phillips, Ph.D.)

20 Ironwood

If Falconina kills ant queens in California, it may indirectly give invasive Argentine ants (Linepithema humile), arguably our most damaging invasive insect, an even greater competitive advantage over native ants. Unlike new queens of many native ant species, new queens of Argentine ants are always protected by nestmates — workers accompany them when they leave their parental nest in a process called “colony budding” (analogous to vegetative reproduction in plants). Thus, new Argentine ant queens are likely far less vulnerable to Falconina predation than new queens that must fend for themselves. If this is the case, Falconina might disproportionately kill California’s native ant queens, such as those of Harvester ants (Pogonomyrmex spp.), further enabling the spread and dominance of Argentine ants. Another important bit of information we don’t know is the extent of Falconina’s invasive range. Observations on iNaturalist.org suggest Santa Barbara County or Ventura County marks Falconina’s northern range limit on the west coast (https://www.inaturalist. org/observations?taxon_id=70360). The spider is nocturnal and cryptic, so these few observations could represent just the tip of the Falconina iceberg (apologies for the image, arachnophobes and icebergophobes). If community naturalists like yourselves continue to post Falconina observations on iNaturalist.org, it can help resolve where the spider lives and breeds and how common it is in our area. Eventually, this data could be used to track Falconina’s possible northward range expansion. O

‘‘Falconina gracilis, there’s no need to kill us’’

Ants are brimming with poetry. They can’t stop reciting the stuff. It’s unnatural.

Late one night in Austin, I overheard a colony – one especially prone to lyrical outbursts –begging Falconina to leave it alone. Begging in rhyme, of course. I doubt the spiders heeded the message: In morbid jest

call you “Success”

you go straight to our heads In all seriousness

really a pest

humanity’s

Works Cited:

Fowler, H. G. 1981. Behavior of two myrmecophiles of paraguayan leaf-cutting ants. Rev. Chilena Ent. 11:69–72.

Phillips, Z.P. 2021. Dispersal of Attaphila fungicola, a symbiotic cockroach of leaf-cutter ants. University of Texas at Austin.

Valle, S. J., C. B. Keiser, L. S. Vincent, and R. S. Vetter. 2013. A South American spider, Falconina gracilis (Keyserling 1891) (Araneae: Corinnidae), newly established in Southern California. The Pan-Pacific Entomologist 89:259–263.

Contact

If you think you’ve seen Falconina in the area, please contact the author.

If you are an ant brimming with poetry, please do not contact the author.

Acknowledgements Thank you Alex Wild for permission to include your photographs.

7: Falconina gracilis captures and eats a carpenter ant (Camponotus sansabeanus) queen during feeding trials. (Photo: Zach Phillips, Ph.D.)

We

You’re

Have

Ironwood 21

Because

you tried eating crickets instead? People say they’re good, A sustainable food! A growing part of

diet And if you could We know that you would Ape the bipeds – don’t you deny it But you’re stuck Mimicking us, An homage we could never disdain We make a fuss Only because You won’t stop eating our brains Sincerely, Ants

22 Ironwood

Pruning Natives Demystified

By: Keith Nevison, Director of Horticulture and Operations

No single task in the garden seems to provoke as much apprehension, drive so many questions, and result in such feelings of satisfaction (if done correctly!) as plant pruning. Artful pruning of plants is something that can take years to master, but the good news is that by following certain guidelines and paying close attention to the plants in your garden, you can get more comfortable with this necessary practice and enjoy it each gardening season.

Why Prune?

Generally speaking, pruning is done to remove the three Ds: deadwood, diseased, and dangerous material. Pruning can also be done to customize shape or tame an overgrown specimen. Here are some examples:

• Tree branches that are crossing or rubbing can put a lot of stress on a plant, so it’s best to remove an offending branch, keeping the strongest, most vigorous shoots or those branches aligned with the desired overall shape.

• When approaching an overgrown or leggy plant, pruning all the way back to basal growing shoots is sometimes the appropriate route and will result in a new lease on life.

• If you’re faced with a tree or woody shrub that is severely overgrown, make a three-year (or more) plan. Remove a fraction of the overgrown material each year. This more patient path can prevent shock and stress to the plant that results from removing so much of its photosynthetic capacity all at once.

When To Prune

A lack of hard frost in many areas of California means that we can get by with pruning later into the season, and tender new growth is at less risk of cold-winter damage. Even still, it is important to consider the seasonality of the blossom cycle when pruning any plant, especially shrubs. As a rule, avoid making any cuts once active growth has started, so as not to cut off flowering potential and prevent awkward “shooting” as the plant tries to recover from injury. Therefore, the best time to prune most California native plants is toward the end of the dormant season, September through December, or before early spring rains cause plants to wake up and grow

profusely. Exceptions would be in colder parts of the state (USDA Plant Hardiness Zones 4–9), for specific species, or for pruning out the three Ds. Attend to the three Ds anytime to mitigate risk to plants and damage to humans and structures.

Tools for Pruning

It is important to start with sharp, well-maintained bypass hand pruners aka secateurs. Use any brand you’d like, so long as you keep them clean and sharpened, and they fit your hand ergonomically for comfort and safety. At Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, we are fans of Swiss-made Felco, and these are standard issue for every member of our Grounds Team (and we also sell them in our Garden Shop). Japanese brands like Okatsune or ARS are also solid bypass pruner investments that should last for many, many years through your gardening career. (Please be careful. Carbon-steel blades are super sharp!)

For cutting plant material larger than .375 inches (9.5 millimeters) in diameter, a set of long-handled loppers is a wise purchase that should get plenty of use when tackling trees and shrubs. Bypass loppers typically cut branch material up to 1 inch (25 millimeters) thick with ease, and the longer the handles, the more leverage you’ll have for easier cuts.

For any material larger than 1 inch (25 millimeters), a fine-toothed folding saw is a device that will get plenty of use in the garden, especially when working tree branches that are smaller than necessary for a chainsaw. The saw brand that I prefer is Japanesemade Silky, but there are many quality products on the market. (We also carry Silky saws in the Garden Shop.)

Ironwood 23

When it comes to chainsaws, our Grounds Team has started moving increasingly toward electric models. These are great when only a few larger cuts are required, or you need to make several small cuts that don’t necessitate the extra horsepower of a conventional saw. The ease of starting an electric saw with a trigger, rather than mixing oil/gas and then pulling the cord to start a “normal” saw, is wonderful and makes one appreciate the advances of modern technological garden tools.

How to Prune (Native) Plants

Most cuts can be boiled down to either tipping or thinning: removing small parts of existing branches or entire branches altogether.

Smaller tipping cuts done during the growing season are typically stimulative, spurring a plant into vegetative growing action. These are the cuts used when shearing a hedge to reduce its overall growing height and to fill a plant out. Here at the Garden, you can see an example of this in our lemonade berry hedge (Rhus integrifolia) that rings the historic courtyard by the Shop and Garden Nursery.

Thinning cuts, by comparison, are made to achieve a desired overall form, getting rid of awkward branches or removing water sprouts that emerge from latent buds after a heavy pruning. When making thinning cuts, it’s important to preserve the branch collar (the band of tissue formed at the juncture of a trunk and its branches) that will eventually grow over the wound, disinviting disease.

Also, one overall tip. When reducing top growth in a tree or shrub, select a lower branch that is at least one-third or greater the diameter of the material above the cut. This helps to prevent premature death or other problems to the specimen receiving the pruning.

Good Techniques Equate To Good Results

Here at the Garden we are hygienic in our approach to pruning, making sure to sanitize all cutting surfaces with a disinfectant to avoid spreading diseases from unhealthy plants to healthy ones. Alcohol (70% or higher concentration) is a good standard disinfectant for disarming most plant diseases and typically doesn’t pose a safety risk to operators, nor tools. Disinfection is important for preventing undesired spread of pathogens like bacterial blights (rose family plants are especially susceptible), rusts, mildews, etc. An easy method for applying alcohol is to carry a small spray bottle with you while pruning, applying whenever you move between plants or more often if working on a particularly diseased specimen.

Pruning Popular California Species

Clearly, California has A LOT of native plant species. The California Native Plant Society lists approximately 6,300 species in our state, with 2,153 endemics (occurring only within our boundaries). To address all possibilities is beyond the scope of this article, but let’s address a few shrubs, perennials, and trees that are common and beloved in our Garden and local environment.

Buckwheats (Eriogonum sp.) are LOVED at the Garden and by native pollinators! These plants are the ultimate summer garden shrub, with a long-lasting floral display that attracts bees and other insects in droves for several months. They also happen to be very easy to care for, with no pruning recommended other than deadheading, but again, this practice takes away seedheads that would otherwise attract songbirds and other creatures. Most buckwheats will not recover after a hard pruning, so go lightly if desired at all. Buckwheats will also self-seed in a garden, especially where a light mulch layer or open soil is present. We think the spent seed heads are attractive in the late-fall garden, so we leave them for wildlife and beauty.

California lilac (Ceanothus sp.) is one of our prettiest native shrubs in spring and a host plant for several types of butterflies and moths. Ceanothus can be trained to become bushier through pinching or lightly pruning in spring, post-flowering. It’s generally recommended not to prune any growth larger than a pencil as it can make plants susceptible to fungal infections.

Manzanita (Arctostaphylos sp.) is another iconic shrub, found extensively in chaparral ecosystems throughout California and the West. Manzanitas are recommended to be pruned from just past flowering season to early summer. Be aware, that pruning spent flowers will impact the “berry” display and, hence, wildlife attraction to fruits. Don’t prune manzanitas in wet months to avoid spread of fungal pathogens.

The Garden’s Grounds Manager Stephanie Ranes offers a bunch of tips on pruning manzanitas: “To promote a denser form or to shape the overall plant, pinch or tip prune in March/April while growth is still tender. Flower buds for the following spring are set in May through June, so if these buds are pruned, the plant will not flower the following spring. Look for new growth without flowering buds or tip only some branches with buds to allow flowering in the following spring. Older plants can be pruned or thinned in summer to reduce their overall size, remove excessive branches, and expose the branching patterns that bring manzanitas fame. Manzanitas heal slowly,

24 Ironwood

so prune carefully into live branches to avoid any unnecessary opening or injury in live material. Make cuts close to the branch without nicking or peeling any bark from surrounding branches. Manzanitas won’t generally recover from a hard pruning, so it’s best to prune or thin lightly every year, if needed at all. Dead branches/wood can be removed any time of year, but make pruning cuts carefully to avoid cutting into any live bark when removing old material.”

Sage (Salvia sp.) is an iconic, aromatic shrub of the West. California sages can be pruned to create a denser habit in late summer/fall by cutting back to one-third or one-fourth of the overall plant. Note that many birds will forage sage seeds, so leaving spent flower stalks (instead of deadheading spent flowers) into summer can be beneficial to wildlife. Stephanie says, “Experimentation in the Garden has shown that even very old Salvia (five to eight years) with very woody stems have succeeded in regenerating after being pruned very hard (most to all of the plant cut back). Regeneration after a hard pruning like this was aided by a deep soaking of the plant and only recommended if the plant has become too large, woody, and leggy to prune lightly. To achieve a denser, more ‘manicured’ form with Salvia, the best approach is to tip prune or pinch new growth at the ends of branches while the plant is actively growing in winter/spring. This technique will affect flowering as Salvia bloom from the end of branches, but it can also help encourage denser growth on the plant overall for future years.”

Sumac (Rhus sp.) is popular here, occurring in the Garden and in our surrounding environment, including lemonade berry (R. integrifolia), aromatic sumac (R. aromatica), sugar bush (R. ovata), and laurel sumac (Malosma laurina). Many of our sumacs handle pruning well and can tolerate shearing or shaping at any time of year. These plants are highly adaptable, excellent for erosion control as bank stabilizers, and serve as host plants for various lepidopterans (butterflies, moths, and skippers). Lemonade berry is the plant that we have sheared as a hedge in our historic courtyard. Plant one (or several) and have fun!

Toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia) is one of the most common naturally occurring shrubs at the Garden and our wildlife love this plant. With it putting on an excellent display of “Christmas” berries, it’s best to prune toyon sporadically, if at all, over the course of the year. If a heavy pruning is desired to tame a large, unsightly shrub, it’s best to attempt in late summer, roughly August or September. After any heavy pruning, it’s recommended to give a plant extra

water to avoid overly stressing it. Toyon has evolved to crown sprout after fires, but this feature should not be overly tested with aggressive yearly pruning in too short of a time frame, for fear of stressing and exposing to various pathogens. O

Ironwood 25

Inside the Garden Nursery: Staff Tips for Fall

By: Zachary Kucinski, Plant Sales Coordinator and Living Collection Assistant

Over the years I’ve worked at the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden Nursery, I’ve heard all kinds of questions about planting native plants. Can toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia) grow in shade? My soil doesn’t drain well; can I still plant matilija poppy (Romneya coulteri)? Will my coast sunflower (Encelia californica) pair well with my sage (Salvia)? It doesn’t need watering if it’s drought tolerant, right?

I like to tell visitors that gardening with California’s native plants is a dance: not every move will be perfect and your timing might be off, but it’s all about learning and enjoying yourself. You’ll have successes, but you’ll also find opportunities to improve as you develop your garden. One of the many joys of home gardening is truly learning your site — what plants work where and how they change over the seasons.

With this article, I hope to clear the canopy of confusion and let some sunlight in on the topic of native plant gardening. I want home gardeners to know they have a green light to experiment with native plants. To start, here are some of the most pressing questions I routinely receive, as well as a few guidelines to consider as you continue your gardening journey.

I’m overwhelmed. I know the benefits of native plants, but I don’t know where to begin.

You don’t have to transition your entire garden space. Start small! Even a single native plant is a step in the right direction and can reveal a lot about your garden’s conditions.

Pro tip: Pick a corner of your property that you walk past daily. Someplace you are familiar with where you can keep an eye on your new plantings.

What do I need to know about my site before choosing plants?

One of the first things to consider is the amount of sun your specific site receives. Does it get morning shade and afternoon sun? Is it blasting hot or is there an overhead canopy of shade? Is your site irrigated, or do you hope to rely mainly on rainfall? Is the soil heavy and muddy when wet, or does it drain water relatively quickly? Answering these questions will help get you on the right path.

Pro tip: Plant for the most extreme conditions of the site. For example, if your spot has morning shade and

hot afternoon sun, try a plant that does best in that hot sun and trust that it will tolerate the mild morning shade.

How do I choose the perfect plant?

The truth is, the perfect plant is the one you love and are able to get established. In some cases, it may take a year or two of that plant being in the ground before you realize if it was or was not the right plant for the spot. We even deal with this at the Garden! What most people see when they visit the Garden is a curated

26 Ironwood

Zachary Kucinski outside the Garden Nursery.

Ironwood 27

symphony of native plants, but behind the scenes, our dedicated gardeners are always removing plants that didn’t make it and experimenting with new ones.

Pro tip: There are great resources to help guide you. If you can make it to the Garden, our staff is ready to help or check out some of the books available at our Garden Shop. There are also great online resources on our website (SBBotanicGarden.org/grow), as well as at Pacifichorticulture.org or Calscape.org, just to name a few.

I am at the Garden Nursery, standing among all the happy plants. Where do I go from here?

Welcome! There are a lot of awesome plants to explore at our Nursery, especially during the fall planting season, which kicks off in November. Start by reading the care cards to get a sense of how each plant will act in your garden. See if the average growth sizes will work for your area and if the conditions preferred are a match for your site. While these cards are based on years of horticultural insight, they are guidelines. Every garden is different and the more you know about your specific space, the more you can tailor these guidelines to your needs. For instance, I recently planted California fuchsia (Epilobium canum) in heavy shade, despite the fact it generally likes sunny habitats, but it has bloomed all summer long. I think that’s a success!

There was this plant … it had leaves and flowers. Do you have it for sale? Did you see something in the Garden that you liked? Did you get something last year that took off, but you can’t remember what it’s called? It’s a lot easier to identify a plant from a photo than it is to verbally describe it. Many plants may look similar, but they can vary drastically when it comes to how to care for them, so being able to identify a plant sometimes requires zooming in on the details.

Pro tip: Bring several photos of the plant you’re interested in. Make sure you get a couple of close-up shots and blooms if you can. Nursery staff should be able to help you identify it or find something close.

I’m looking for something specific, and I can’t find it.

Ask us! Our inventory is always changing and plants are constantly being shuffled around. There are more than 6,000 plants native to California, and, unfortunately, the Garden can’t carry them all. We do our best to keep a large variety available year-round.

Some plants are easy to find and are growing in our Living Collection Nursery that could be ready in just a few weeks. Other plants are difficult to propagate and slow growing, which means they can take months before they are retail ready (if they’re available at all). If you’re curious about a specific plant, please ask our staff. Although never guaranteed, we can put your desired plant on our wish list, and we will keep an eye out if it does become available.

Pro tip: When a plant is in bloom at the Garden or around town, there is a higher demand for that plant and subsequently can be harder for us to keep in stock. For example, if you want a bush anemone (Carpenteria californica), don’t wait until it blooms in April. The time to get it is when you see it available!

Does my drought-tolerant plant really need additional water?

So many of California’s native plants are drought tolerant, emphasis on the word “tolerant.” As in they put up with drought, causing many of them to go dormant or lose leaves in drought conditions. While this strategy is advantageous in a wild setting, it may not be preferable for home gardeners. Supplying additional water to your native plants helps keep your plants greener and may help them bloom longer.

Pro tip: Native plants are less thirsty than a traditional garden, so adjust your irrigation accordingly.

Wait, I have more questions!

The Garden wants you to be successful when it comes to native-plant gardening — that is at the heart of our mission. We’d love to help you along the way.

Pro tip: With our website update, we now have an option for you to submit questions directly to our Horticulture Team. Visit SBBotanicGarden.org/grow/ gardening-resources and scroll to the bottom of the page to submit your question.

With some of the basics now under your belt, we hope you’ll join us in cultivating biodiversity right in your backyard by growing native plants. Even just one to get you started can be a catalyst for change. So, start small and build a relationship with your plants and property. You’ll soon find what works to make your garden thrive. And remember, your garden is a living and changing place. Some plants will take off, and others might not, but you won’t know until you give it a try.

We look forward to seeing you in the Nursery soon. O

28 Ironwood

Become a Member Nurture Nature Become a member today by contacting us at membership@SBBotanicGarden.org Join us as we build a community of native plant advocates and lead a movement toward a healthier planet — one native seed at a time. Ironwood 29

From the Archives: Designating California’s State Tree(s)

By: Hannah Barton, Archivist

By: Hannah Barton, Archivist

While coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens and giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum), collectively known as redwood trees, are not necessarily synonymous with our local Santa Barbara region and its Mediterranean climate, it’s nearly impossible to see these trees and not think of California. They are inextricably linked, especially given the fact that 95% of the distribution of these trees in the wild is within the confines of our state borders. It’s no wonder then that these redwoods should hold the honor as our official state trees, a designation since 1953.

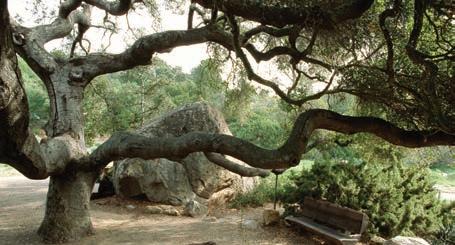

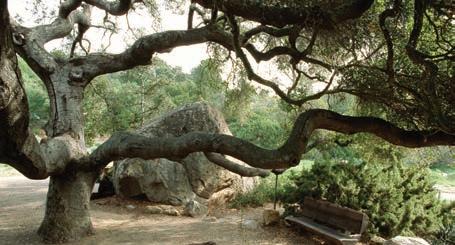

Here at Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, we are fortunate to have our own dedicated redwood ecosystem, perfectly situated along Mission Creek, a small representation of the northern coastal forests where these giants thrive. And, did you know that our dedication to the redwoods goes one step further? In fact, our very own Maunsell Van Rensselaer (known as Van), director of the Garden from 1936 to 1950, was responsible in 1936 for proposing the designation of the redwood as California’s state tree! With the support of state Senator John J. Hollister Jr., Van’s

30 Ironwood

Santa Barbara Botanic Garden redwoods, today (Photo: Trainor) Maunsell Van Rensselaer, 1942

proposal made its way to the California Legislature in early 1937. The “California redwood” was adopted by the California State Assembly as the official state tree in 1937 and officially added to the state statutes in 1943.

This little bit of Garden history is yet another reminder that our mission reaches beyond the confines of our Garden grounds. By supporting and cultivating native plants and ecosystems not typically found here on the south coast, we can educate and inspire our visitors and transport them throughout our beautiful and diverse state. While we want to encourage and empower everyone to cultivate native plants that are most appropriate to their specific locales, we recognize that we are part of the greater California ecosystem and we remain dedicated as ever (and as proven since 1936!) to the majestic redwoods that symbolize our great state.

Want to learn more about Van, his role in designating California’s state tree, and his other conservation work? Check out Hannah’s article on our website at SBBotanicGarden.org/insights. O

Santa Barbara Botanic Garden redwoods, 1959 (Photo: Tomlinson)

Santa Barbara Botanic Garden redwoods, 1959 (Photo: Tomlinson)

Ironwood 31

Maunsell Van Rensselaer, 1940 (Photo: Wilkes)

Member Story: Moving at the Speed of Nature

By: Katherine Sanders, Digital Marketing Coordinator

Isat with Lori Robinson on the Caretaker’s Cottage deck, situated just below the Garden Nursery at Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, the morning sun peeking between the leaves of the Roger’s red grape (Vitis ‘Roger’s Red’) that climbs the trellis over our heads. It was the perfect setting to get to know Lori, an author, a safari specialist, a self-proclaimed “wild keeper,” and, more recently, a volunteer docent at the Garden.

A Heart for California

Growing up a total animal lover — idolizing Jane Goodall in a goats-and-raccoons-and-alligators-aspets kind of family — inspired Lori’s broader love of the natural world. “I’ve always wanted to help wild places and wild animals,” she recounts. Even though Lori was raised in Florida, her story is deeply intertwined with California and its landscape. “I was supposed to be born in California,” Lori beams. “My parents met at Stanford. They were married, and then they got pregnant with me, flew to Florida, and

never came back. So I was born there, but California is in my genes. I always knew I was going to come back here.” A hawk calls in the distance, punctuating Lori’s sentiment.

Lori first moved to California to study at the University of California, Santa Cruz, majoring in environmental studies and biology. After graduating, she left the state to work for the Animal Welfare Institute in Washington, D.C. She began writing about whaling issues, factory farming, and animal experimentation and testing. The work wore on her though, and she found herself hopeless and distraught by the weight of these issues. “At the time, I believed I was too sensitive to endure the work,” Lori admits, “but in time I saw that I was just young, impatient, and naïve about how long it takes to create change.”

Falling in Love with Native Plants

Lori eventually found her way back to California and this time to Santa Barbara. After buying a home,

Lori Robinson in the Garden, 2022 (Photo: Greg Trainor)

32 Ironwood

she connected with the Garden and started taking gardening classes. It wasn’t long before she realized her home garden could be more than beautiful. It could make a real difference. “I learned about the benefits of planting with native plants and it became such a passion of mine. We can all grow native plants to help ‘save wild.’”

Let Nature Set the Pace

This notion steered Lori in a different direction than her time in D.C. had. “We can all have a patch of the Garden at home, even if it’s just a native plant on our patio.” She acknowledged the sometimesparalyzing feeling people face when trying to decide what, where, or how to start planting native plants, but, she continued, “Gardening at home gives me a sense of control. It makes me feel like I can actually do something instead of [single handedly] stopping climate change and a potential sixth mass extinction, which feel so big I don’t know where to start.” She explained Douglas Tallamy’s newest book, “Nature’s Best Hope,” which is about this exact concept. Lori expressed a sense of hope about Tallamy’s message. “Can you imagine if we all filled our gardens with even a few native plants? It would create a little ecosystem route for native pollinators to follow!”

Taking even small steps like these offers a tangible solution to the complex and abstract challenges we face with the climate and biodiversity crises. For many though, this action may seem too small and the fact that natural processes don’t have immediate results only heightens their indecision. “The barrier to entry is low though,” Lori stressed. “You just need to start with one plant.” And though it takes a few seasons for plants to establish themselves, she explained, “You

have to be brave enough and patient enough to let the system start to work in its natural way.” It’s sage advice that’s evident all around the Garden.

Finding Nature Everywhere

Some years ago, Lori started leading safari tours in Africa as part of the Jane Goodall Institute. “Everything in Africa is so big. The spaces, the trees, the animals. It’s incredible,” she waved her arms to emphasize. “People go to Africa and they say, ‘Oh my gosh, the animals!’ and honestly, we’ve got them [here in Santa Barbara] too, but they just look different.” We often consider our wild animals — skunks, raccoons, opossums — pests more than majestic creatures. “You can’t say, ‘I don’t like skunks,’ but like birds. They all kind of work together and rely on each other,” Lori illustrated. This thinking aligns with the Garden’s

Ironwood 33

Lori Robinson on safari in Africa with the Jane Goodall Institute (all photos).

mission to conserve native plants because they, in turn, sustain all life on Earth.

In leading safaris, Lori noticed people have a way of thinking they need to “go to nature,” but she emphasized that nature is everywhere. “Try going outside your door and allow for the same kind of openness you’d have when you go on a hike. That same feeling can be found right on your patio with a little care.” Lori had been learning recently about the idea of a sit spot, which inspired her to start her own practice. “I sit outside with a cup of tea every morning. The key is to have a spot you can go to every single day for the same amount of time. It helps create the familiarity and the patience to notice things, big and small.”

The Feeling of Home

The appreciation for California as a biodiversity hot spot was always in Lori’s sight line, and now not only does she live here, but she gets to spread her joy and respect for nature as well. “I love this place,” exclaimed Lori about the Garden, “and now, being a docent, I’m able to encourage people to plant with native plants.” She noted that people make mistakes “like spraying, cutting down, planting the wrong things.” But we can course correct. The Garden is a great teacher in that regard. As Lori encouraged, we need to plant natives and then “slow down to let nature do its thing.”

The Legend of Zia, the First Dog Member

There is a story amongst Santa Barbara Botanic Garden staff that Lori Robinson and her shelter rescue pup, Zia, are the unintentional pioneers of dog membership at the Garden. Whether fact or fable, it can be said that the Garden embraces furry friends and the curiosity that sometimes comes along with them.

Once upon a time, Lori and Zia often went on early morning walks in the Garden. Lori admitted, “Early enough that I could get away with letting her off leash.” Zia, ever the explorer, loved to sniff around and tuck into culverts. On one such morning walk through the Arroyo Section, Zia followed her nose into a culvert, but moments later, Lori realized Zia couldn’t back herself out. “I couldn’t see her, but I could hear her whining.” Lori flagged down Garden staff for help and eventually site plans were tracked down to trace the culvert’s path. Perhaps they could dig to free Zia? After several unsuccessful attempts, the fire department was enlisted in the rescue effort. The clever firefighters made their way to the other end of the culvert and finally coaxed Zia out. Five hours after nosing her way in, Zia exited to a cheering crowd, seemingly unphased by the hullabaloo that had taken place to free her. Lori recalled, “The next day, I picked up the phone and made a donation to the Garden and asked if Zia could be an honorary member.” The curiosity of Zia the dog lives on in legend — and, some say, through a $30 dog-membership program and novelty pet bandana! SBBotanicGarden.org/support/ membership

Create Your Own Sit Spot

One of Lori Robinson’s favorite ways to connect with nature is through the practice of a sit spot. Authors Jon Young, Evan McGown, and Ellen Haas describe this practice in their book “Coyote’s Guide to Connecting with Nature.” Lori explained, “I’ve been doing this simple but profoundly rewarding activity for the past few years.” Here are the basics to get started:

1. Find a place in nature. Your chosen place can be in your garden, a park, the woods, or even on a balcony facing a tree.

2. Once you find your spot, visit that place every day for a set amount of time (30 to 45 minutes is ideal but modify if necessary).

3. Sit still and quiet and simply notice. Engage all your senses to observe what is happening in the natural world around you.

The authors’ practice focused on birds. Lori focuses on anything to do with the natural world. At first you may not notice much, but in time and through the seasons you will start to notice the routines and transitions of flora and fauna, including a more micro view of the world of bugs and gradual landscape textures. “Watch, listen, and learn — that’s how we best build and deepen our connection to all the wonders of nature.”

O

34 Ironwood

Lori Robinson and her dog, Zia, in Santa Barbara

Become a Volunteer Make Friends and Help Us Grow. Get Started Today. SBBotanicGarden.org Become a volunteer today by contacting us at volunteer@SBBotanicGarden.org We will match your interests, abilities, and availability with the Garden’s current volunteer needs. By becoming a volunteer, you will be making a substantial contribution to the preservation of California’s native plants and habitats. Ironwood 35

Field Notes: Poetry Inspired by Nature

M. L. Brown is the author of “Call It Mist,” for which she won the 3 Mile Harbor Press Book Award, and “Drought,” for which she won the Claudia Emerson Poetry Chapbook Award.

A poet and book artist, she grew up in New Hampshire and earned a bachelor’s degree from Connecticut College and a master’s from Antioch University, Los Angeles.

When not writing, Brown, a resident of Mission Canyon, devotes her time to raising funds for Planned Parenthood and curates the poetry section for their annual book sale.