THE FUTURE OF FOOD AND SOCIAL JUSTICE:

A YOUTH STORYTELLING PROJECT

2023-24 STATE OF THE TUCSON FOOD SYSTEM REPORT

EDITED BY LAUREL BELLANTE Artwork by Kaleigh Brown.

Artwork by Kaleigh Brown.

2023-24 STATE OF THE TUCSON FOOD SYSTEM REPORT

EDITED BY LAUREL BELLANTE Artwork by Kaleigh Brown.

Artwork by Kaleigh Brown.

We live and work on stolen land. Today, Arizona is home to 22 federally recognized tribes, with Tucson being home to the O’odham and the Pascua Yaqui, whose relationship with this land continues to this day. Some of the oldest known agricultural practices in the United States have roots in the Tucson basin and southern Arizona. The people, culture, and history of this region allow us to live, build community, and grow food on this land today. We respectfully acknowledge our individual and collective responsibility to address the ongoing legacies of dispossession and exclusion in the region and aim to cultivate a more just present and future. We offer this acknowledgment with appreciation and gratitude to the original inhabitants, their love for the land, and the sacrifices made to protect and sustain the land and all our relations.

The Future of Food and Social Justice: A Youth Storytelling Project (FFSJ) was supported by two Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI) seed grants from the University of Arizona.

Kaleigh Brown..................................................................................................

Zabrina Duran..................................................................................................

Cesilia Garcia...................................................................................................

Rezwana Islam.................................................................................................

KALEIGH BROWN | 22 YEARS OLD was raised in a white, middle-class family in Tucson, AZ. She recently completed her undergraduate degree in Film and Television Production and Environmental Studies at the University of Arizona and is now working as a freelance filmmaker. During her time as a part of the Food Justice Storytelling cohort, she endeavored to create visual projects that share the myriad local ways anyone can participate in and promote food justice.

ZABRINA DURAN | 23 YEARS OLD was born and raised in Tucson, Arizona. She is a student at the University of Arizona majoring in Environmental Studies and Geography with a minor in Sustainable Built Environments. For as long as she can remember, she has been passionate about the environment and its well-being. Growing up in Arizona, she feels deeply connected to the Sonoran Desert, her community, and her Mexican, Chinese, and Hopi cultural backgrounds. She believes that a key part of building a sustainable and resilient future relies heavily on community-based work and that is where she would like to focus her work in the future.

CESILIA GARCIA | 22 YEARS OLD grew up in Bisbee, Arizona, a small border town. She is a History and Political Science Major with a minor in Adolescent, Community, and Education. She enjoys food history and finding out anything that people ate in the past and how it has evolved into the food that we know now. She is also passionate about learning about past struggles and social justice and hopes to help fight against injustices. The storytelling internship has been a combination of all her interests. After she graduates, Cesilia plans on teaching high school social studies and hopes to work in government one day.

is a senior at the University of Arizona double majoring in Public Health and Creative Writing with minors in Natural Resources, Nutrition and Food Systems, and Korean Language. She’s interested in multidisciplinary work looking at the connection between public health, food, and the environment with a focus on global fisheries. As a child of Bangladeshi immigrants, the preservation of cultural food practices is important to her, especially Asian food cultures and street food culture. After graduation she will pursue a M.S in Sustainability and Development at the University of Michigan.

is a Diné storyteller, activist, artist, and student. She is from Teesto, AZ, but was raised in the outskirts of the Navajo Nation in Winslow, Arizona. Currently pursuing bachelor’s degrees in Food Studies and Nutrition and Food Systems at the University of Arizona, Tommey is passionate about uplifting Native literature. As a dedicated Diné poet and creative, Tommey uses storytelling as a tool for advocacy and empowerment, striving to foster strength and unity within Indigenous communities.

graduated in Spring ‘23 with her BA in Food Studies at the University of Arizona. She is of Swedish and Texas heritage and was raised in Tucson, AZ in an upper middle-class neighborhood. As a Tucson native with childhood travels to India and abroad, and a former baker, she has grown passionate about food and how it relates to both culture and community in diverse ways. She has channeled this passion into her volunteer work for Iskashitaa Refugee Network and Flowers and Bullets and continues this passion through her current work at the Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona as the Farmers’ Market Network and Advocacy Coordinator for the weekly Santa Cruz River Farmers’ Market.

OLD grew up in the Sonoran Desert with her hometown being Tucson, Arizona. Things she loves to do include hiking, cooking, gardening, learning about medicinal plants, and practicing jiu jitsu. She graduated from the University of Arizona in 2023 with a B.A. in Food Studies and is looking forward to spending more intentional time cooking and connecting with her family and community through food. Paloma’s Food Studies major taught her a lot about history, what food means to herself and her community, and she sought to showcase these meanings in her food justice stories.

| 30 YEARS OLD is pursuing his bachelor’s degree in Agriculture, Technology and Education at the University of Arizona. He has lived most of his life on the Tohono O’odham reservation located in the Sonoran Desert of southwest Arizona. As a youth, he grew fond of agriculture and how it pertains to the cultural roots of his people.

is a queer, Xicana, Citizen Band Potawatomi, and of German descent. She is a tamale enthusiast, food on the water admirer, sweet on pan dulce, fangirl of the Three Sisters and the list goes on. Besides being a big fan of food, Jäger believes that food is medicine, central to culture, and the importance of working towards Indigenous food sovereignty. Currently, they work as a Research Coordinator at the Tishman Center for Social Justice and the Environment at the University of Michigan.

MAEGAN LOPEZ | MENTOR AND SCM is Tohono O’odham and from a community called Wejij Oidag or New Fields. She has one son, his name is Maximus. Maegan works at a unique place called Friends of Tucson Birthplace Mission Garden, an ethnobotanical, historical 4-acre museum, as a Gardener/Cultural Outreach Specialist. Gardening, being out in the desert to harvest wild foods, and learning from others is a big part of Maegan’s background and what her job encompasses. As a child she followed her grandparents around when they would harvest wild plants for basket weaving. She has had many O’odham teachers who inspired her to learn more about O’odham himdag (way of life) and how important it is to pass along their inspiration to others.

CLAUDIO RODRIGUEZ | MENTOR AND SCM is a community organizer, artist, and storyteller. Raised in south side Tucson, he approaches his work with an asset-based approach, emphasizing the power of reconnecting individuals to the land for social change. His focus includes environmental justice, food security, and empowering communities through this holistic approach.

NELDA LILIANA RUIZ CALLES | MENTOR AND SCM is a fronteriza community organizer, cultural worker and educator born in Ambos Nogales in the Sonoran Borderlands. Nelda has been organizing in the south side of Tucson since 2010, connecting communities with the resources they may need to create safe, healthy, and regenerative communities; she develops leaders and mobilizes communities with the grassroots crew Armando Barrios as part of Regeneración. Additionally, she serves as a program manager and educator at the Southwest Folklife Alliance, overseeing the folklife PAR network—a platform for community-driven participatory action research initiatives nationwide where everyday people learn together and share cultural expressions to make long term change.

LAUREL BELLANTE | SCM is a human-environment geographer with a focus on critical food studies, food justice, and sustainable food systems in the US-Mexico Borderlands and Latin America more broadly. She is an assistant professor of practice in the School of Geography, Development, and Environment and assistant director of the Center for Regional Food Studies at the University of Arizona. She loves working with students and is passionate about leveraging university resources to support positive food systems change in our region and beyond.

MEGAN A. CARNEY | SCM is a feminist medical and sociocultural anthropologist specializing in critical migration and diaspora studies, the politics of care and solidarity, and critical food studies. She is associate professor of Anthropology and director of the Center for Regional Food Studies at the University of Arizona.

DEYANIRA IBARRA | RESEARCH ASSISTANT is a Chicana birthworker and socioculturalanthropology Ph.D. student at the University of Arizona with research interests at the intersection of reproductive autonomy, landscapes of care, and networks of solidarity in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands. Deyanira completed their B.A. in Women’s and Gender Studies at Wellesley College and M.S. in Narrative Medicine at the University of Southern California.

The Center for Regional Food Studies (CRFS) launched the Future of Food and Social Justice: A Youth Storytelling Project (FFSJ) in 2022 as a pilot internship program to mentor and support undergraduate students in sharing their food stories. Since Tucson was named an UNESCO City of Gastronomy in 2015, there has been an upwelling of interest in southern Arizona’s food and agricultural practices. With this internship, we endeavored to diversify the stories being told about food in our region, particularly by highlighting the experiences and aspirations of youth. For whether as first-generation college students, food service workers, children of farmworkers, emerging scholars and activists, or inheritors of food traditions and cultural wisdom, youth are frequently on the frontlines of our food system and yet their voices are too often absent from the stories we tell. By uplifting the stories of young people, particularly young people of color, this compilation aims to attend to this narrative absence and remind us of the abundance of critical perspectives, deep questioning, and profound insights that young minds have to offer related to our food systems, foodways, and the future of food justice.

Funded by two internal Hispanic Serving Institution grants, the project was guided by a paid 6-person steering committee that included community organizers and food scholars (2 Latinx, 2 Native, and 2 white). The steering committee coordinated the call for applications, led food justice and storytelling workshops, and mentored interns as they developed their stories. After circulating the call for applications, 14 undergraduate students from a diversity of backgrounds and disciplines were selected as the first cohort of storytelling interns for the 202223 academic year. Each intern was matched with a food justice mentor and participated in bimonthly mentorship circles and monthly workshops. While mentorship circles allowed for a mutual learning process and time to reflect together on food justice in both theory and practice, monthly workshops trained students in topics ranging from the ethics of research and storytelling to writing food memories, operationalizing a racialized right to food, defining food justice, and strategies for telling and disseminating food stories.

In this pilot year, FSSJ interns were invited to create stories in any modality and on any food-related topic of their choice. This openness was a deliberate strategy, one that honors the many ways of knowing and communicating. It allowed stories to emerge organically and encouraged students to articulate the stories they most wanted to tell in the way that felt most authentic to them. And the outcomes have been astounding. The re-

sulting stories range from podcast interviews with local activists and Indigenous leaders to poems, beadwork, children’s stories, collage, embroidery, digital stories, recipe books, prose, and more.

In this project, we look to storytelling as both a means and an end. It was reaffirmed early on that the process behind creating and sharing stories is as vital as – and perhaps even more important than – the end products, the final stories. Throughout our time together, we engaged in mentorship circles in which all of us were both mentors and mentees, involved in a mutual learning process. Through deep listening and vulnerability, we engaged in cross-cultural and inter-generational dialogues that led all of us to enrich our perspectives and deepen our understandings about complex social issues. In sum, each of us, whether mentor or mentee, were transformed by the process itself.

Beyond the works featured in this compilation, interns have also shared their stories in other spaces. In June of 2023, eight interns and four mentors presented this work at the Agriculture and Human Values Conference in Boston, MA. Six mentors and four students co-wrote a chapter for a forthcoming edited volume by MIT press, entitled Nurturing Food Justice, in which we reflect upon our experiences from the pilot year of this project and emphasize youth storytelling as a key tool for working towards food justice. Lastly, several food stories, including a video of our storytelling showcase from December of 2023, are available on our Center website at www.crfs. arizona.edu. We hope you enjoy the stories featured in this compilation and perhaps even get inspired to create and share some of your own stories.

This project came to center around seed saving because of my interest in the agricultural histories of the region that the city of Tucson inhabits. I have lived in Tucson, Arizona my entire life and thought I knew everything there was to know about the place where I grew up. I came to realize just how wrong I was in my sophomore year of college when I learned that this region is home to one of the longest known areas of continuous agricultural cultivation in the United States. Such an impressive fact came as such a surprise to me. What else did I not know about this desert and the people who have lived here? What could this information teach me about our future here?

Seed saving has become a more and more discussed practice over the years as people realize that communities are at risk of completely losing plants that once grew or were cultivated regularly. Seeds that hold significance to Indigenous communities have been particularly at risk. In the Southwest, precious food crops such as the tepary bean and 60-day corn are not grown in large-scale agricultural operations which is where most people acquire their food =. If these crops are not being consumed then they are at risk of not being grown and passed down.

It is particularly important to work with these plants and to keep them alive because they are adapted to this environment and are thus able to withstand the high temperatures and dry soil of this land. Similarly, native pollinator plants are more resilient to the local climate and can be more readily placed in regions experiencing erosion or lack of pollinators. It is important not only environmentally but also culturally to nourish these seeds as communities prepare for future problems.

Local groups and organizations such as Mission Garden, Pima County Public Library’s Seed Library and Borderlands Restoration Network are places that are actively working to save seeds and get them out into the land. For this photo essay, I visited the facilities of these three groups and documented their various processes. By compiling them into one essay, I aim to provide the viewer a sense of what seed saving entails and what it looks like for these communities.

The essay consists of thirteen photographs, four of which are hand-embroidered. Though this work is digital, I wanted to add a tactile element in the form of embroidery that encourages the viewer to imagine what these seeds will turn into. It is an invitation to create the future of the food we consume and, more broadly, the future

of the land we live on. During preparation for the embroidery, I digitally sketched out what I was planning to do on each of the four photographs. I referenced images of each plant and recreated the shapes of their leaves and flowers onto my photos. As the creator, this time-intensive process made me focus on the small details of everything. Every choice matters when you’re physically manipulating the photo. Similarly, the choices we make today regarding our environment are critical and have impacts that ripple through our lives.

I hope this series of photos offers a short introduction to seed saving and to the different resources available here in the region. The image is a powerful method of storytelling as it can convey an entire perspective to someone in a few seconds’ time. However, this is a particular experience of seed saving in the region. I invite you to discover seed saving and growing opportunities in your life by checking out some seeds from the Pima County Public Library’s extensive seed library or observing native plants being grown at Mission Garden.

I grew up amongst the unmistakable sights, smells, and tastes of a health food store, specifically the New Life Health Food Center on Speedway Boulevard in Tucson, Arizona. It was routine for my grandpa to pick me up from school in his dusty Toyota pickup truck and drive us to New Life where we would wait impatiently for 8 PM when my step-grandma, the store manager, could lock up for the night. If boredom struck, I would embark on grocery adventures. A table by the entrance piled high with books on herbal medicines and the next vegan diet ready were intriguing for a bit but the real entertainment lay ahead. The poor lighting at the back of the store provided the perfect opportunity to sneak around in the darkness like a spy deciphering names of teas stocked against the wall and deftly evading customers. Finally, 8 PM would arrive. My step-grandma would pull out her keys and lock the doors, jiggling each handle. I would watch over the counter as she worked the register. Click. Click. The numbers would eventually match up, meaning we were excitedly closer to going home.

Now, I take Speedway Boulevard on my daily commute to college. Where New Life should be, there is now nothing but empty windows. The family running the store closed its doors in 2017. National grocery chains were popping up everywhere, many with health and wellness selections, becoming fierce competitors to small, family-owned health food stores. On one hand, spaces like New Life have largely disappeared and are something most people can no longer experience. On the other hand, for many, access to such stores has always been out of reach. Such stores were not only few and far between but were often more expensive than chain stores. My heart aches to once more dance down the aisles with my step-grandma after locking up for the night. But I long even more for everyone to have more equitable access to the foods once found in stores like New Life.

In my series of embroidery pieces, I sought to pay homage to the significance of the agricultural traditions that have sustained the Akimel O’odham tribe for generations. As Arizona has been facing an ever-growing drought, many wonder how the people here will be sustained if the land is not able to keep up with how food has been grown with our current agricultural practices. When looking for sustainable options for the future of food and agriculture in places like Arizona, it is important to recognize the people who have lived on this land for thousands of years and the knowledge they hold that has helped them live from the land. Each piece in this series aimed to showcase a few of the crops that are still being grown by the Akimel O’odham tribe, as well as the Gila River itself. Water is life, and for the Akimel O’odham, it is a resource that helped keep their culture alive. During the late 1800s, Akimel O’odham and other tribes in the Gila River area lost access to their water. They saw the Gila River dry due to the water used upstream in the growing Phoenix urban area. In recent years, the Akimel O’odham people have fought and regained water rights to the Gila River! Regaining water rights is an incredible feat when considering the long history of water governance in the Southwest and how many tribes still do not even have access to clean water in Arizona. Obtaining water rights has helped preserve intangible cultural heritage practices such as traditional farming alive and well. More about the history of water and the Gila River Indian Community can be learned at gilariver.org. These embroidery pieces celebrate the Akimel O’odham culture, the Gila River, and traditional Indigenous farming.

Hello I am Cesilia Garcia. I come from a small town in Southern Arizona called Bisbee, Arizona. I am an American-born Mexican-American. Some of the foods that connect me to my culture are enchiladas, tacos, and posole. These dishes are some of many that I enjoy but are also ones that I have made to stay connected when I am away from home. Enchiladas are my favorite food; I order them a majority of the time whenever I go to a Mexican restaurant. Tacos are my second favorite. I enjoy how easy and versatile they are; I can make them from leftovers, and they are an easy way to connect with my culture. Posole is one of my favorite soups; it is usually eaten during the holidays and when it is cold, so I have special memories of eating it for Christmas or New Year.

I decided to make this poem because I was in a time when I felt a little disconnected from my family, and I wasn’t eating things that I grew up eating. It made me feel sad; as much as I enjoy other cultures’ foods or new and different foods, I felt like something was missing from me eating things I grew up eating. During this time, I was also away from my family, and I realized food helped me feel more connected to them even if I was away from them. Something as simple as cooking enchiladas made me feel happier. To me and my family, food is not just something to survive, but it helps me connect with my culture and the people around me. Food is central to my culture. We place a lot of emphasis on it for many different traditions and holidays. It is also a thing that my family uses to connect with our ancestors.

My friend tells me she made dharosh bahji yesterday because she missed eating it. She’s Bangladeshi but the type of Bangladeshi where she’s from Bangladesh unlike my Americanized self. She shares this moment with me because I know what dharosh bahji is. I nod and tell her “honestly that’s such a mood” as if I’ve ever felt that way in my life. My mom is right there at home. If I ever wanted dharosh bahji, which I have never craved in my entire life, I just have to ask her to make it. She would probably sigh and tell me she has to make something else for dinner so my older brother, who is 27, would actually eat it since he doesn’t like Bangladeshi food.

When writing this, I had to Google what the best way to describe dharosh bahji in English is. Spiced sautéed okra seems to be the closest description although dharosh means okra and bahji means fried. The technical definition for the dish would be fried okra but in America that is something else. A favorite of the south, fried okra in America refers to okra covered in buttermilk and cornmeal before being deep-fried to form a crispy, delicious, and golden surface. My friend doesn’t know that fried okra exists. She has no context for American food outside of burgers and pizza and the other foods that appear on TV and commercials. I’m the American here. I know what Southern fried okra is, even if I’ve never tried it myself.

Two weeks ago, she was surprised to hear that I didn’t know how to read or write Bangla. Then she asked me to say something in Bangla with the same kind of sick fascination white people do when they hear I’m bilingual. They wanna see just how bilingual I am. I refuse because I know I’ll stumble over my words, my American accent always feeling like a glaring neon sign that obstructs what I’m trying to say.

When I was 8 I got voluntold by my mom to read a traditional poem at a cultural gathering. I sat there, legs folded under me, holding a creased paper, and dressed in a yellow and red sari that I had already crumpled up while playing with my friends earlier. I recited a traditional poem where the narrator asks a squirrel if he eats white guava. I know the fruit being referenced is a white guava because I just Googled it. Until now, I didn’t know the English word for the green, round, crunchy but with a soft seed filled core fruit that I grew up being coaxed into eating. My mom begged me and my brothers to at least eat one or two pieces while my dad eagerly devoured it. I willingly eat white guava unlike my brothers and will admit, I feel a sick sense of superiority over them because of it.

While reading the poem, I mispronounced the word ‘squirrel’ and an uncle from the crowd loudly corrected my pronunciation. It got a lighthearted giggle from everyone because I was a cute little 8 year old, still with baby fat on my round cheeks, still young enough to play with dolls, still stumbling over words in English as well. But being corrected in that manner was so embarrassing I never wanted to open my mouth again. I wanted to stay silent my entire life if it meant my Bangla wouldn’t be laughed at. The laughs weren’t malicious. It was because I was a little kid making an endearing mistake. But to me it was one of the numerous reminders that I’m not “really” Bangladeshi.

Like white guava, which I grew up always hearing being referred to as peara, there are a lot of words for different foods that I didn’t know the English equivalents to. Once I went grocery shopping with my mom. She sent me off to the produce section in Safeway to get her thonnaipata. It was only once I arrived in the produce section that I realized I had no idea what thonnaipata was in English. It was leafy and small and used as garnish sometimes. Probably parsley or cilantro. But which one? I paced back and forth between both herbs as they sat there in their own designated spaces, looking perfectly innocent with their fresh, green flesh covered in water droplets from the mini shower they had just received and racked my brain for a way to tell the difference. In the end I found myself staring helplessly at the vegetables before slinking back over to my mom and asking her what thonnaipata was in English. She laughed and told me it was cilantro. I felt like an idiot the whole walk back to the produce section where I finally snatched up a bundle of cilantro and hurried back. I was 19 at the time.

Dharosh, kathal, thonnaipata, taetool. Okra, jack fruit, cilantro, tamarind. A sort of shame fills me when I struggle to find the words to describe my own foods. Whether it’s having to Google the proper translation for something, having to confront that I have no idea how certain foods are made or admitting that I’ve never tried

something all Bangladeshis have ‘supposedly’ eaten. Being Desi itself complicates it. Pani puri. Once I got asked by a friend from India if I like pani puri. I twisted my shirt in my hands and admitted I didn’t know what pani puri was. I got a dramatic gasp, one playful, but unnecessary just the same. I’m brown, how can I not know what pani puri is? I consulted my friend Google again that night. Phuchka. Pani puri is the Hindi word for what I grew up knowing as phuckha.

I don’t know how to describe phuckha. It’s a small puffed crispy bread that is dipped in a mix of spiced water. I have tried phuckha. I didn’t like it. At community parties I still get offered it by the older aunties and uncles and no matter how long I’ve known them, I always feel awkward saying no.

Phuckha is a street food. You can find it being sold by the side of the road at a small stand. There is always a giant plastic bag filled with the little breads perched on top and a jug of the phuckha mix next to it. A large ladle is used to pour the mix into the breads which have been broken on top, with each portion consisting of 4-6 breads. The owner barehanded serves dish by dish on actual dishes that are only hastily rinsed off before being used for the next patron. He shouts with customers to overcome the crushing noise of metro Dhaka, taking taka and tucking it into the hem of his lungi, repeating the procedure over and over to meet the needs of children finishing school, other street sellers who need a snack, and people stopping by during errands. It’s a stall that serves everyone and anyone. I have never tried phuckha from a street seller. I have never tried any food from any street seller. My delicate, sensitive, westernized digestive system would cease to function if I ever tried street food from Bangladesh. I’d get violently sick, quite literally unable to stomach the food of the everyman. It’s not just phucka. It’s also peara cut into the shape of flowers, speared onto wooden sticks and carried by the fistful by young boys that weave through the ever-present traffic jams. They are just one of many sellers there in the street, including others selling popcorn, balloons, or garlands made of belliphol, known as Arabian jasmine in English. Someone in an adjacent car rolls down his window and buys a peara as I watch, feeling a sort of envy because I can’t do that. I can’t eat things like that. But I can eat sushi. I can eat nopalitos, I can eat kimchi. I’ve eaten bison and raw oyster and blue cheese and a whole list of things that the everyman in Bangladesh has likely never tried.

Yet this doesn’t soothe me. If anything it makes things worse. I can’t eat my traditional foods but I can eat everyone else’s. Although are they actually my foods? Even the food I crave when I’m in Bangladesh isn’t really Bangladeshi food. I crave the pizza from a local chain called Bella Italia where I relish in knowing that all the meat options are edible to me because it’s guaranteed to be halal in a Muslim majority country. I crave two pieces of toast made from the rickety old toaster in my maternal grandparents’ house, one slice covered in orange marmalade and the other slice in honey. The house is technically my uncle’s now since both my grandparents have passed but I will always think of it as my grandparents’ house.

Toast with orange marmalade and honey was a breakfast staple for my grandfather, who would eat quietly in the morning, his grey hair combed neatly, skin softened from age, and with a calm and affectionate demeanor that was apparently a far cry from his childhood self. My grandfather was always an active person and excelled in sports like boxing. He also got himself into trouble a lot, playing pranks and not studying as well as he should have been. My grandfather served in the Bangladesh army during the Bangladesh Liberation War in the 1970s, an event well known to anyone over 50 that grew up listening to the Beatles. He didn’t want to go to college, but my great-grandfather wouldn’t let him just sit around the house.

One of the things my grandfather did after he finished his army service was found the company Pran with his friend. Pran has grown into one of the top food manufacturing companies in Bangladesh. Pran makes a number of products, but I would dream of amar shokto, a thick, chewy, mango flavor fruit leather type sweet. My grandfather would bring multiple boxes back home because I could easily inhale one box all by myself in only two days. Sometimes he’d bring back a snack called layer cake, which was two small cakes with either chocolate or vanilla spread in between, or a chewy sugary milk candy that stuck to my teeth. I would collect the wax wrappers printed with little cows in my hand as I ate one after another. My grandfather left this earth 8 years ago. I haven’t had any of those foods since.

Time apart from my favorite things isn’t an experience unique to food. I haven’t seen my paternal uncle since the last time I went to Bangladesh in 2016. I miss him. I miss his tall stature, and voice when he inevitably argues

with my dad, his sloping nose, and teasing voice, asking us how are you, what you doing these days, did you finish school. I miss being younger. Back when my Bangla was better, back when a chilled candy bar instantly perked me up instead of giving me a sense of tiredness as I wonder if the weight gain and inevitable acne is worth it, back when I was small enough to use my uncle as a jungle gym. Back when I was young enough to not realize that the passage of time means aging and that the grey hairs that have started to dominate my uncle’s and my father’s hair as they get close to their 60s foreshadow an inevitable event that I want to pretend will never happen.

My paternal uncle isn’t married and doesn’t have kids so when me and my brothers visited, he had a chance to spoil us with treats. The first thing he’d hand us when we’d walk into his apartment, which was on the 4th floor of a building with no elevator, was a refrigerated Mars bar. You can find Mars bars in America but it’s more common in the UK, the mere presence of the candy bar a reminder of the colonization that plagued Bangladesh less than a 100 years ago.

My paternal grandmother lived in the apartment on the floor below my uncle. She was a small woman to start, age making her even smaller, with thick glasses and a face nearly identical to my father. She would hug each of us and as me and my siblings grew into our early teen years the hugs became to feel more and more awkward. She’d shoo us into the dining room and ask for food to be brought out. Steaming plates of rice and lentils and vegetables and chicken would come from the kitchen as me and my siblings stood and watched, the three of us already lined up in front of a little sink like ducklings, ready to wash our hands. The tap water in Bangladesh isn’t treated water like the tap water in America. It needs to be boiled to be safe to drink. However, the three American kids, still grumpy after a nearly 24 hour long journey, needed to wash our hands and rinse our plates in boiled water too because that’s how poorly prepared for Bangladesh bacteria our bodies were.

I always ate with my hands. My older brother asked for utensils. My younger brother, still in elementary school at the time, ate with a spoon because his hand-eye coordination wasn’t quite good enough to not drop rice all over himself. My grandmother would ask how we were doing, and my older brother would answer first because despite his reluctance to participate in our food culture, he is the most fluent in Bangla. I’d follow up with some broken Banglish, looking at my mom with desperate eyes, begging her to save me until she took over the conversation. My mom automatically answered for my little brother since he definitely wasn’t going to answer the question himself.

The fridge at my grandmother’s always had a brand of ice cream that didn’t exist in the United States. It was inspired by Italian desserts with layers of chocolate, vanilla and lady finger cookies, the texture of the ice cream itself airier than the ice cream found back home in Tucson. Sometimes the fridge would have mishti, traditional Bangladeshi sweets, from the sweet shop near the apartment building. When we were called over for snack time and I stood behind my brothers, waiting for my portion of ice cream, I would stare at the magnets on the fridge. They were made of wood and shaped into different fruits and vegetables and painted with gloss paint that made the mango magnet especially look very appetizing. I loved those magnets. I loved rearranging them, messing with them, marveling at the blend of colors. Apparently, I had this habit since I was a child, a weird kid who was a big fan of grandma’s fridge magnets regardless of whether I was 3 or 13. My grandmother passed 10 years ago and I still miss how she smelled when she would hug me.

My 14-year-old self didn’t have the self-awareness to cherish the time I had with my grandmother. As I watch time pass, I desperately hope my 25-year-old self won’t make the same mistake I made with my grandmother with my uncle but the distance between me and my uncle seems to grow wider every day. I don’t know how to fix it. Whether it be through food or phone calls I find myself helpless in front of the gaping void that is connection.

My uncle isn’t married but wedding biriyani is one of my favorite foods in the world. The good stuff is nearly impossible to get outside of Bangladesh. Bangladeshi weddings are already chaotic by nature, with 4 or 5 events all in the course of a few days from each other which means all hands on deck for family members as we wrap presents, marvel over the vibrant colors of the bride’s new sari, and argue about how to arrange things. In America a large wedding might have 100 people. In Bangladesh a large wedding will have 1,000. A wedding is something everyone is invited to. Family and friends aren’t enough. Your extended family, your parents’ friends,

co-workers, the cousin of a cousin you’ve never met in your life. Everyone shows up to give the couple well wishes. Casual acquaintances will pop in to congratulate the couple and eat before leaving while friends and distant family will stay through the entire event. The people closest to the bride and groom, best friends and close family, are there the entire time, before the event even begins until the bride and groom have to all but kick guests out of their house.

What events are put on depends on what the couple wants. Some people go simple and modern with the traditional Gaye Holud and the wedding reception. Others go over the top with 6 or 7 different events. The most I’ve seen is a wedding that started with a women’s only henna party, followed by a Gaye Holud, where guests smear turmeric paste on the bride and groom to offer their blessings, then the Nikkah ceremony where the couple is married in the eyes of Islam, then the biggest event which is the wedding itself whether the couple is married in the Bangladeshi way, traditionally held by the bride’s family and finally the bou bhaat, a reception held by the groom’s family where the new bride is introduced to everyone. A lot of these ceremonies exist because of old traditions or outlooks that no one cares about anymore, but the celebration and chance to see family members or friends you haven’t seen in years makes it worth it.

Wedding biryani is usually served during the main ceremony. Things really start the moment the bride begins getting dressed hours beforehand. There’s a flurry of saris and hairpins and makeup and jewelry and heels and safety pins that get pinned into the fabric of the bride’s sari to make sure everything stays in place. The bride’s family arrives first and then blocks the door to the venue so when the groom’s family arrives they can demand a satisfactory dowry, a tradition that these days is all for fun and show since anything related to money is decided well in advance. There is the arrival of gifts like jewelry and clothes, greeting relatives you didn’t even know existed and countless pictures with family, friends, and complete strangers. Piles of steaming lamb biryani on huge metal plates are brought out and served, most people drinking a glass of borhani, a spiced yogurt drink, on the side. Dessert is mishti of all types and pistachio kulfi served in little clay pots. The happy couple departs to their marital home in a car decorated with flower garlands of rose, jasmine or marigold. When the bride and groom have arrived at their shared living space, they find more flower garlands decorating the doorways and bed, the entire house seeped in the scent of flowers. Gifts are moved in, tea is served, and another hour is spent talking about this and that at the kitchen table. It finally ends at 2 or 3 am and everyone heads back, stomachs stuffed with rich foods, collars that have been unbuttoned down to the chest, heavy jewelry and tight clothes that make bodies ache and leave marks on the hips and waist, lips devoid of makeup since whatever was on it has smudged off onto the rim of teacups long ago, and eyelids heavy with sleep.

The last time I had wedding biryani in Bangladesh was in summer of 2016 when my cousin got married. My mom and I made the 24-hour long journey there to celebrate. My maternal grandfather had gotten hip surgery a few days earlier after a sudden fall but was doing well. Things were strange and silent once we were picked up from the airport by my grandfather’s long-time driver who I had known my entire life. When my mom and I walked into my grandparents’ house and saw all the family gathered in the living room it had become obvious what had happened. There are only two things that will bring the entire family together like this. Weddings and death. That summer I inhaled four plates of biryani at my cousin’s wedding and tasted the mishti offered during repast at my grandfather’s funeral for the first time.

I can’t separate Bangladeshi food from the various threads of my past. It’s not something like Japanese food or Italian food where I eat it because I think it tastes good. Everything I’ve eaten has been gifted to me through the things I’ve gone through and the people in my life. A sweet vermicelli pudding called shemai that I eat half asleep with porota, a type of bread, at 6am before Eid prayer. Bhaba pitha, a steamed coconut dessert stuffed with jaggery, that my father learned to make in batches since his mother wasn’t there to make them herself anymore. Khichuri, a mix of rice and lentils that ends up bright yellow because of spices, that my mom makes when it’s raining because that’s just what Bangladeshi people do. Haleem, cooked lamb in a heavy broth with lentils that is served during Ramadan. Ilish fish, the official fish of Bangladesh, that my mother always cooks during the monsoon season, even though it takes forever to pick the bones out. Food always brings memories with it, whether I want it to or not. It feels overwhelming at times and I feel like I’m drowning in a wave of culture and tradition I don’t have the right to drown in.

These days I introduce myself as Bangladeshi-American because regardless of how close I want to be to Bangladesh, at the end of the day, I’m not just Bangladeshi. I’m also the kid who grew up eating tacos and fry bread and Eegee’s and girl scout cookies. There’s too much American in me to just be satisfied with Bangladesh, whether it be the food or the culture or the people. As I grow older, I’ve started to try and come to terms with my identity. I don’t think I resent it anymore. It’s still embarrassing, and I still find myself cringing at times when I jumble words up in my mouth and I still worry that I won’t ever really be Bangladeshi. But as I move on with life, as I move away from my parents to start a new journey somewhere else, I think one day I will end up missing dharosh bahji and that’s Bangladeshi enough for me.

Tucson, Arizona is on the native lands of the Tohono O’odham and Yaqui people. Saguaro fruit has been of cultural and religious significance to the Tohono O’odham for centuries. Saguaro fruit harvest season is in late June or early July and marks the start of the Tohono O’odham new year. When I was younger, I was given the privilege to participate in a saguaro fruit harvest which gave the inspiration for this piece.

The sight of tall green kings is sublime

Dusting mountains and peaks that show the ticking of time

From woven baskets to plastic tubs perched on the hip

That will be covered in color that dyes the fingertips

Hold a rib of the ancestors that reaches to the sky and splits

Lashed together with cat-claw and creosote bits

The dust underfoot billows up in small puffs

While the rocks of the earth are still rough

Tip your head up-up-up and gaze at the crown

Appreciate the view as it will soon be coming down

Some wear a promise of sticky sweet juice that looms

While others wait patiently for their velvet white blooms

At first the job will be slow

As newcomers must understand the flow

Of picking and plucking and passing around

Before they tumble into the white plastic bucket on the ground

Children shriek and are getting excited

As they wait patiently to be guided

Through gentle hands and warm words

Stories that only through lip are told

The split open fruit shines magenta in the sun

As buckets and baskets are filled one by one

Full of seeds, small and black

To cut one open, one needs the knack

Avoiding spines while letting fire lick

Burning away that which can prick

The surface is smooth like polished gems

The flesh inside soothes the people who picked them

All surrounded by chattering mouths

Down in the warm, dusty, south

Where Arizona and Mexico join hands

Rock layers, and mountains, and a ground covered in sand

This piece is an exploration of indigenous (food) futurisms. It was modeled on where I am from, which is Teesto, Arizona and the scenery from around that area. You can see Saddle Butte in the background, a traditional hogan, horse trailers, a sheep corral, and my brother and I tending to the crops in the field. This piece can tell us that Native people can rematriate, plant, cultivate, and harvest our own foods again. The interaction with the land and wildlife in the piece shows that engaging with the landscape/desert as a whole evokes an entire ecosystem that is the ultimate teacher for my people.

The reconstruction of traditional food systems is seen as imperative to the cultural restoration and health of all Native people. This piece demonstrates that in the effort to do that, we may not get completely back to how we lived long ago, but we can get to a place where our next generation can. Because food sovereignty is not a final state we can achieve, but rather a process, a method, and a movement. This piece is intended for everyone to dissect and talk about, because the disruption of Native food systems completely shifted all aspects of our well-being and not many know about that issue.

as the earth gently releases her roots I make my way towards you; you’re kneeling in the sand I admire your hair that mimics the flow of water and trace the curvatures of your moccasins with my eyes until you said –close your eyes sister –feel the gentle pull of the wind you swayed along with the feather weed grass cornmeal falling out of your hand, onto the dirt where our másání planted her crops so long ago and not long ago, these homelands felt so foreign to me so, I knelt down next to you and solemnly prayed for forgiveness. you looked at me with an aching heart and said: sister – this is your home you’re no stranger here mornings like these adorned with blue hues of light I’m reminded that medicine is plenty here with sage, yucca, juniper, milkweed… one plant pulled and another takes its place only aboriginals can enact this practice. after five hundred years, reformation is what it is. indigenous futurisms is. what. it. is. do you even know what that is?

it is strengthening our plans to revitalize foodways reexamining and reshaping our methodology so, we can return to our original instructions to protect the soft earth from which we were formed this gentle earth that has sustained our livelihoods nurtured us in times of brutal deprivation with her, I have absolutely no questions I trust her answers. since she has created my entire being indoctrinated intrinsic relationships and entire communities in prayer so – in what ways can I give back to something that has sustained me even before birth? since my ancestors? since time immemorial? today, my sister and I are planting for nahasdzáán for the future. for generations that will exceed our mortal life because that’s what it is to be indigenous

a mirror of a belief system that took me years to possess so, let me put on some KTNN while we plant we’ll morn with the land to some Alan Jackson about his down-and-out-love affairs and find a way to compare our situations to his songs while we plant this memory garden then we’ll rest and I’ll lean onto you like corn stalks when they’re too tall because sister – I love you I write this with every voice you have given me we are tótsohnii women, co-depending kin we travel the path of water to this garden we’ll plant more and more seeds until the crops make its way towards great másání’s house on the plateau where all her grandchildren raced down the hill to get to the garden that was planted where we are planting today. so, they could grab the biggest and juiciest watermelon where they are now our mothers, our fathers, our aunties, our uncles. because that’s how it works. before you know it, we will be them and our children will be us before we began planting you grabbed my hands and said –to ensure strength for our people, tether your love to these tiny seeds and sprinkle them gently in the pit of dirt this will continually and beautifully allow the land to be: youthful, an elder, morphine, ever giving, and glittering forever.

Translations (Navajo to English): másání – maternal grandmother nahasdzáán – the Earth / our mother tótsohnii – Big Water Clan (Tommey’s first clan)

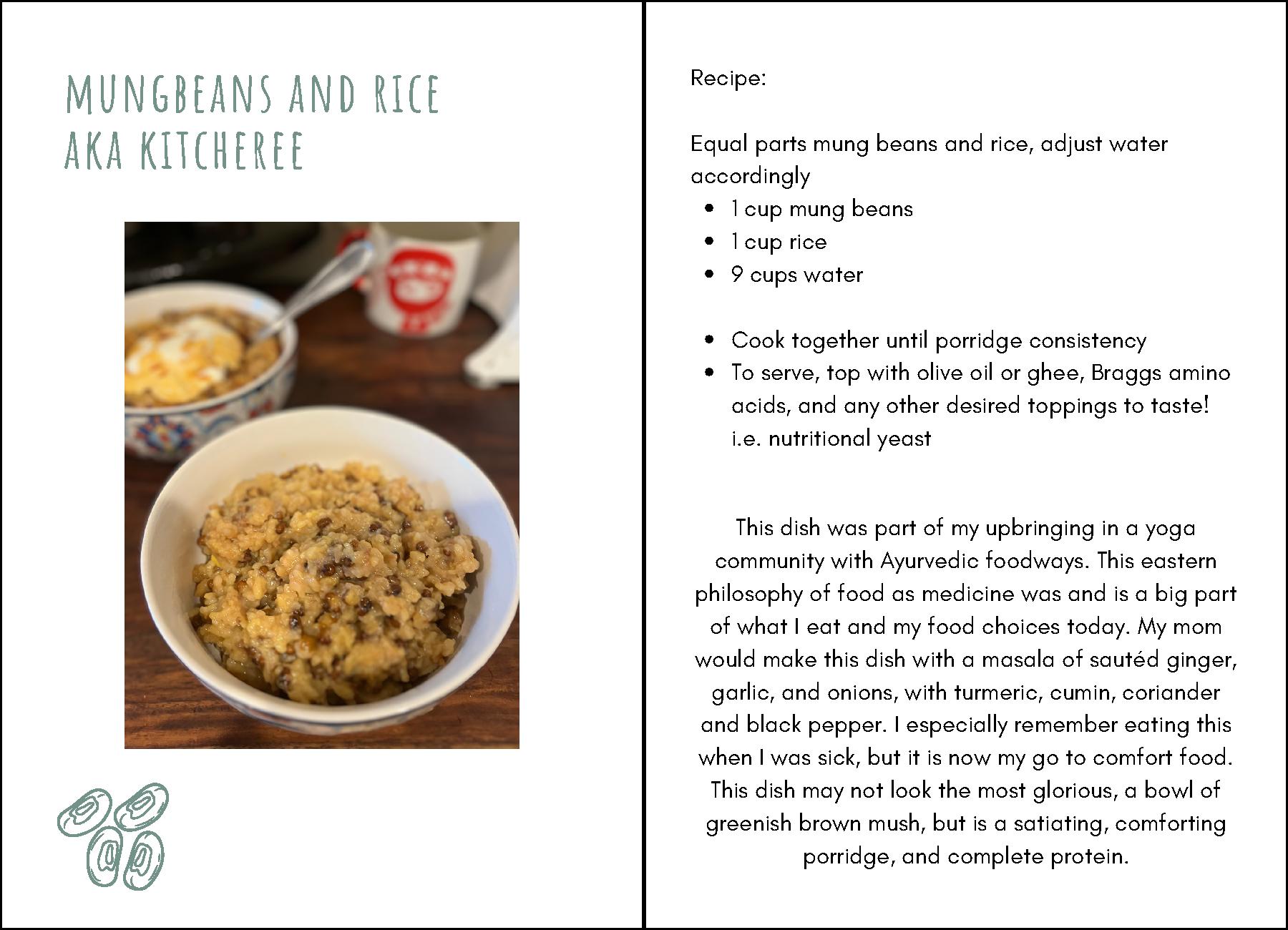

This is a story of my life through foods that hold dear memories and significant impacts from my multi-cultural upbringing: Swedish mother, Texan father, adopted Punjabi culture, and vegetarian household. I have chosen certain dishes and recipes that reflect and have influenced who I am today through the many experiences and backgrounds I come from. All from a vegetarian perspective.

Many people connect to their roots, culture or heritage through the foods they eat and hold dear. For me, these foods come from a myriad of backgrounds. My mother’s grandparents immigrated to the U.S. from Sweden between 1905 and 1910, adopting and assimilating into the U.S. culture. My father’s ancestors immigrated to the U.S. starting in the 1700s from northern Europe, and ended up as rachers and cowboys in Texas. As culture started to shift in the U.S. in the 1960s both my parents were drawn to Kundalini yoga, vegetarianism and the Sikh religion brought to the states from northern India. They got married in the 1970s and raised my three siblings and me with these diverse cultural influences. Growing up I was exposed to many different foodways that I have come to appreciate in their distinct histories and herigate, while adapting to our family’s dietary preferences and tastes.

Here are just some of the recipes frmo each of my backgrounds that have significant impact on the food identities I hold dear today. View the full recipe book at https://bit.ly/44Bh05x.

For my first Storytelling project I wrote and illustrated a short kid’s book explaining what food means to me. As someone whose dream as a young person was to own a farm, and as someone soon to graduate in the Food Studies degree, it felt like time I shared some of my food journey and to thank many of the people who have helped guide me along the way. I had recently been exploring writing comics and short stories and a children’s book felt like the easiest way to share my reflections and emotions both with visuals and with words. One of my goals was for this book to be read by young students like the ones I worked with in the Manzo Elementary Food Literacy Program. I also wanted it to be interesting to all ages, because anyone can think more about food and what it means to them. And thinking about food, and the heart of what it means to people was exactly what I want to provoke!

For my story project 2, I created a collage of food memories that connect me to my grandmother. At the start of this project, my Nonna (Grandmother in Italian) had recently gone through her months’ long chemotherapy treatments. Her journey called on me to reflect deeply on our memories together, many of which I realized were bound up with food. Whether it was bonding over our favorite snacks like pretzel rods, cannoli’s or learning of my family’s secret recipes through a can of San Marzano tomatoes, I wanted to honor these memories and her legacy in a way that was close to my heart. At the same time, I wanted to honor the stories and ancestors who came to me through many of these foods. Most of whom I have never met, but those whose personalities and beings could seem to be conjured up by a special Sunday Gravy (pasta sauce) or a pot of tea served in her grandfather’s pot. My grandmother’s great grandparents were Jewish, born in Russia. During their time together they had to flee to Poland. Her grandparents were the first to arrive in Harlem, NY, and gave birth to her father in 1910. Her mother was Italian, who’s family immigrated from Napoli to Brooklyn, NY. I carry food traditions from both my Jewish and Italian ancestors and continue to learn more every meal.

Introduction:

Participating in the food justice storytelling internship has allowed me to discover new ideas, build relationships, and look inward, which for me can be hard. The stories I share here forced me to look at myself. For too long I have had a destructive image of myself. Looking back and allowing myself to find the reason why I do what I do has allowed me to recharge my beliefs and continue my path wherever it may lead. I was able to create images of how I feel the plants I grow empower me to grow into the being that I am now. Overall, I would just like to say thank you to those who made this internship possible. It has been a great experience and motivator to speak on a topic that I feel is not talked about enough.

I would like to start my story by saying food saved my life. Like many unfortunate youths, my upbringing was not the greatest growing up in a rural area. The stories I tell embody the beliefs I have about my life. I connect these stories to traditional foods that I have grown. These stories are not to be correlated to my culture; they are simply my experiences. Thank you for reading; I hope you enjoy.

Food, what a universal concept. All living things on earth need food in one form or another. Human beings, I feel, have an extensive emotional connection to the food they consume. Whether it is religious, cultural, or just induces a feeling, food is not only nutritious for the body but for the soul as well. Food to me was a secondary concept in the beginning of my life as I always had enough, which wasn’t easy for my mother having had three boys. But let’s take a quick look at that. For the first portion of our lives, our mother, grandmother, aunts, and parents are the only nourishment we know. There was no ‘this is good or bad’, ‘wrong or right,’ there was just the food that your caregivers gave you. With that in mind, how much of that has shaped your life in how you eat food? I know it has shaped me greatly.

Anyway, going back to the beginning of my life. Memories of food come easy to me from my childhood. Whether it was waking up the vivid orchestra of fragrances such as bacon that filled the room with the intoxicating smell of maple syrup, sizzling butter that created that non-stick layer for beautiful fluffy eggs, or charred white flour dough that came from my grandmothers handmade cemet (chew-ma-th) also known as tortillas. These memories are the fondest I have with my grandmother. My grandmother and I have had a rocky relationship. If I’m being honest the memories of food are my favorite from her because there are so few good memories in between when I was a child. It is a hard issue to realize that abuse can be inherited. My grandmother just had a way of dealing with things and, well, sometimes it hurt. Whether it was emotional or sometimes physical, I understand now that it was how my grandmother was raised and she just didn’t know any other way. Don’t get me wrong, what happened to her does not give her the right nor exempt her of her actions, but I get it. It took me a long time to come to terms with the pain that I was feeling, and to be honest, some of these feelings probably led me down rough paths due to how my mindset was. I do not blame her for any of my choices; they were mine and mine alone, and I feel those choices led me to where I am now. So now why am I ranting on about this, and what does it have to do with food? Well in all that pain, anger, and frustration, I feel food was the way my grandmother showed her love. Though it wasn’t always said, my grandmother put her love into her food. At that time, I never missed a meal, never knew what hunger was, and always knew that there would be a warm plate of food for me when I got home, even if I didn’t always want to go home. My grandmother has a saying: ‘you are to be seen not heard,’ and if you have had the privilege of meeting me you can see how this idea rubs right against my personality. My apologies, just wanted to add a little humor in to my story, but when I compare the past to now, I remember watching my grandmother cooking every morning before I went to school. Preparing dinner when I got done with my homework. Even as a hardened woman, she still made sure that I was fed, and because of her and how much I absorbed I even learned how to cook. Even now as an adult visiting her, the first thing she says is ‘are you hungry?’ I do not know if I will ever fully come to terms with some of my childhood issues, but I do know this: because of food I know that my grandmother did care for me; it was just in her own way.

Independence, as a youth we all crave independence. Well, I can honestly say I was in a hurry to be independent. As a youth I hit my rebel phase hard. I would get in trouble quite frequently whether it was getting busted smoking weed, ditching, vandalizing school property, or other things that I should not have been doing I seemed to keep myself knee deep in… well, you know. These actions would lead me through a hard road of incarceration, expulsion, and eviction. At that time in my life, it was so easy to believe that the world was against me. What a cliché, hmm? I won’t bore you with the many reckless, dangerous, and downright stupid things I did, but long story short, I got kicked out of school. After that happened, my mother thought physical labor would be the best punishment for me. I was sent off to work on a farm for a week at a time where I would stay and work 10 – 12 hours a day. At the time my mother didn’t know just how much this experience would affect my life. Like I said, this was supposed to be a punishment, but in reality, this was one of the best experiences of my life. Learning how to work in a field became a point of freedom in my life. The time I spent preparing, planting, maintaining, and harvesting the fields was truly humbling. To be one with an element and the caretaker of a being that grows solely because of you at that age was a moment of clarity. I grow Tohono O’odham traditional crops. These crops are known as the Ha:l (squash), Hu:n (corn), and Bawi (tepary beans). Growing these plants made me strong, resilient, and hard working. They also gave me a purpose. For a long time, I always felt that I was missing something inside of me, a piece that just seemed to be lost. Learning farming allowed me to finally find the piece that was missing. This piece took the form of culture. As a Tohono O’odham Native American boy, I knew that I was this person, but I never knew what that meant. As I take the time to just sit here and think, I believe now that this means I come from a strong heritage, but there is a lot of wounds that need mended. Knowing that I am this person and being this person are two different things. And I truly believe I am this person now. I am a teacher, student, caretaker, dependent. I am just another seed growing in this field we call earth. I am an Oidagem (farmer)! My people have been here long before I existed, and they will be here long after I’m gone. I just hope that my presence will be known, and when I do go to whatever comes next, I will be able to say I lived, loved, spoke, taught, and shared as much as I possibly could so the O’odham (people) will continue to thrive on this gift of a world we have. So, going back to the seed that changed it all for me. I will leave you with these words. Plant a seed, grow, and I hope you’ll see that any hand can make a difference. One plant can become many, many plants can feed a people, and many people can preserve a world. We just have to be strong enough to make a choice. For me I made the choice to make a difference, however I can.

To integrate social, behavioral, and life sciences into interdisciplinary studies and community dialogue regarding change in regional food systems. We involve students and faculty in the design, implementation, and evaluation of pilot interventions and participatory community-based research in the Arizona-Sonora borderlands foodshed surrounding Tucson, a UNESCO-designated City of Gastronomy, in a manner that can be replicated, scaled up, and applied to other regions globally.