1 minute read

The Wrens of Watu

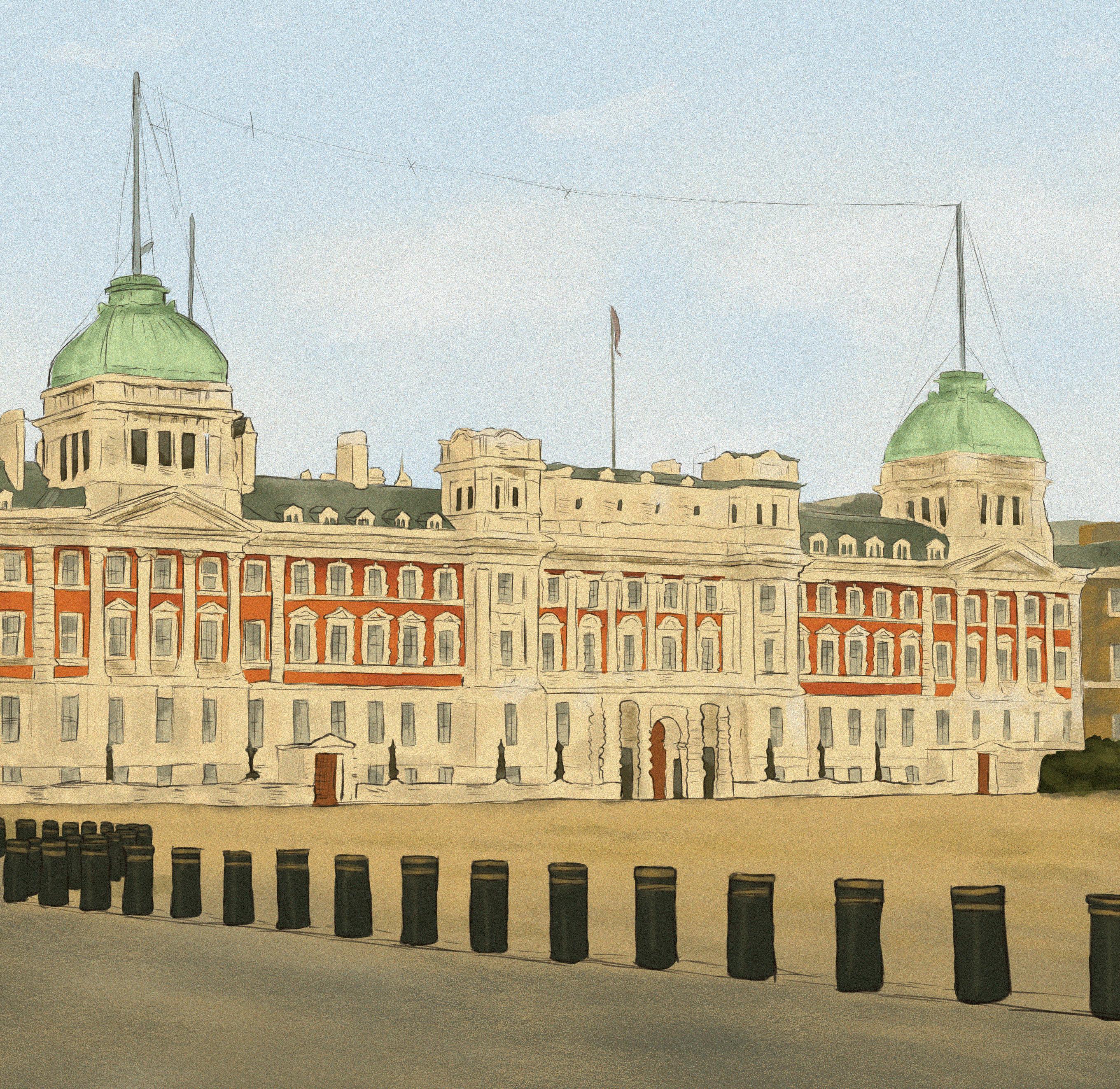

(below) The facade of one of the Admiralty buildings in London. Strategic planning of the Allies on the naval arms race was focused here at the start of the war. The Battle of the Atlantic was the longest ongoing conflict spanning the entirety of World War II. Allied powers fought for control of the sea against German U-boats; and with the British so heavily reliant on trans-Atlantic shipments of raw supplies, food, and oil, it was of the utmost importance for the Allies to maintain an advantage.

Within the Operations Room of the Allied navy’s London headquarters, the Admiralty, was a graph that tracked the number of ships sunk by German U-boats. If the rate of ships sunk significantly outpaced the number of ships built by the Allies, which was denoted by a red line threshold separating the upper fourth of the graph, then the British would have to pull out of the war entirely. No food meant starvation, and starvation leads to surrender. The Germans, however, had taken advantage of their early successes at sea and by the end of 1940 had sunk “more than 1,200 merchant ships, about five years’ worth of construction work in typical peacetime conditions, and more than the rest of the German navy and Luftwaffe combined” (Parkin 60). The Allies were losing, badly, and the chart’s plots were rising dangerously close to the red threshold of defeat.

Advertisement