AN EVENING WITH FRANÇOIS LELEUX

In memory of Emmanuel Cocher (1969-2022) Consul général de France (2015-2019)

Thursday 19 January, 7.30pm The Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh

Friday 20 January, 7.30pm City Halls, Glasgow

Saturday 21 January, 7.30pm Aberdeen Music Hall

Farrenc Symphony No 3 in G minor

Mendelssohn (arr. Tarkmann) Lieder ohne Worte

Interval of 20 minutes

Mendelssohn Overture, ‘The Hebrides’

Schubert Symphony No 4 in C minor ‘Tragic’

François Leleux Conductor / Oboe

François Leleux

4 Royal Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 5AB +44 (0)131 557 6800 | info@sco.org.uk | sco.org.uk

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra is a charity registered in Scotland No. SC015039. Company registration No. SC075079.

Our Edinburgh concert is Sponsored by

Our Edinburgh concert is Sponsored by

The SCO is extremely grateful to the Scottish Government and to the City of Edinburgh Council for their continued support. We are also indebted to our Business Partners, all of the charitable trusts, foundations and lottery funders who support our projects, and to the very many individuals who are kind enough to give us financial support and who enable us to do so much. Each and every donation makes a difference and we truly appreciate it.

Delivered by

Delivered by

Lucinda and Hew Bruce-Gardyne Malcolm and Avril Gourlay

James and Felicity Ivory Christine Lessels

Clair and Vincent Ryan Alan and Sue Warner

David Caldwell in memory of Ann Tom and Alison Cunningham

John and Jane Griffiths

Judith and David Halkerston J Douglas Home

Audrey Hopkins David and Elizabeth Hudson Dr and Mrs Peter Jackson Dr Daniel Lamont Chris and Gill Masters Duncan and Una McGhie Anne-Marie McQueen James F Muirhead

Patrick and Susan Prenter

Mr and Mrs J Reid

Martin and Mairi Ritchie Elaine Ross

Hilary E Ross

George Rubienski

Jill and Brian Sandford

Michael and Elizabeth Sudlow

Robert and Elizabeth Turcan Tom and Natalie Usher

Anny and Bobby White Finlay and Lynn Williamson Ruth Woodburn

Lord Matthew Clarke James and Caroline Denison-Pender Andrew and Kirsty Desson David and Sheila Ferrier Chris and Claire Fletcher James Friend Iain Gow Ian Hutton Gordon Kirk

Robert Mackay and Philip Whitley Mike and Karen Mair

Anne McAlister and Philip Sawyer Gavin McEwan

Roy and Svend McEwan-Brown John and Liz Murphy Alison and Stephen Rawles Andrew Robinson

Ian S Swanson

John-Paul and Joanna Temperley Anne Usher

Catherine Wilson Neil and Philippa Woodcock G M Wright Bruce and Lynda Wyer

Roy Alexander

Joseph I Anderson

Pamela Andrews and Alan Norton

Dr Peter Armit

William Armstrong Fiona and Neil Ballantyne

Timothy Barnes and Janet Sidaway

The Batsleer Family

Jack Bogle

Jane Borland

Michael and Jane Boyle Mary Brady

Elizabeth Brittin

John Brownlie

Laura Buist

Robert Burns

Sheila Colvin

Lorn and Camilla Cowie

Lord and Lady Cullen of Whitekirk Adam and Lesley Cumming Jo and Christine Danbolt

Dr Wilma Dickson

James Dunbar-Nasmith Dr and Mrs Alan Falconer Sheila Ferguson

Dr James W E Forrester Dr William Fortescue

Jeanette Gilchrist

David Gilmour

Dr David Grant Margaret Green Andrew Hadden

J Martin Haldane Ronnie and Ann Hanna Ruth Hannah Robin Harding Roderick Hart Norman Hazelton Ron and Evelynne Hill Clephane Hume Tim and Anna Ingold David and Pamela Jenkins Catherine Johnstone Julie and Julian Keanie Marty Kehoe Professor Christopher and Mrs Alison Kelnar Dr and Mrs Ian Laing Janey and Barrie Lambie Graham and Elma Leisk Geoff Lewis Dorothy A Lunt Vincent Macaulay Joan MacDonald Isobel and Alan MacGillivary Jo-Anna Marshall

James McClure in memory of Robert Duncan Gavin McCrone Michael McGarvie Brian Miller James and Helen Moir Alistair Montgomerie Margaret Mortimer and Ken Jobling Andrew Murchison Hugh and Gillian Nimmo David and Tanya Parker Hilary and Bruce Patrick Maggie Peatfield John Peutherer in memory of Audrey Peutherer

James S Potter Alastair Reid Fiona Reith Olivia Robinson Catherine Steel Ian Szymanski Michael and Jane Boyle Douglas and Sandra Tweddle Margaretha Walker James Wastle C S Weir Bill Welsh Roderick Wylie

We believe the thrill of live orchestral music should be accessible to everyone, so we aim to keep the price of concert tickets as fair as possible. However, even if a performance were completely sold out, we would not cover the presentation costs.

We are indebted to everyone acknowledged here who gives philanthropic gifts to the SCO of £300 or greater each year, as well as those who prefer to remain anonymous. We are also incredibly thankful to the many individuals not listed who are kind enough to support the Orchestra financially, whether that is regularly or on an ad hoc basis. Every single donation makes a difference and we are truly grateful.

Become a regular donor, from as little as £5 a month, by contacting Mary Clayton on 0131 478 8369 or mary.clayton@sco.org.uk

Our Principal Conductor’s Circle is made up of individuals who share the SCO’s vision to bring the joy of music to as many people as possible. These individuals are a special part of our musical family, and their commitment and generosity benefit us all – musicians, audiences and creative learning participants alike. We would like to extend our grateful thanks to them for playing such a key part in the future of the SCO.

American Development Fund

Erik Lars Hansen and Vanessa C L Chang Kenneth and Martha Barker

Creative Learning Fund David and Maria Cumming

Annual Fund James and Patricia Cook Dr Caroline N Hahn Hedley G Wright

Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen

Donald and Louise MacDonald

Chorus Director Gregory Batsleer Anne McFarlane

Viola Steve King Sir Ewan and Lady Brown

Principal Cello Philip Higham The Thomas Family

Cello Donald Gillan

Professor Sue Lightman Cello Eric de Wit Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund

Visiting Artists Fund

Colin and Sue Buchan Anne and Matthew Richards Productions Fund The Usher Family

International Touring Fund Gavin and Kate Gemmell

Principal Second Violin Marcus Barcham Stevens Jo and Alison Elliot

Principal Flute André Cebrián Claire and Mark Urquhart

Principal Oboe Robin Williams Hedley G Wright

Principal Clarinet Maximiliano Martín Stuart and Alison Paul

Principal Bassoon Cerys Ambrose-Evans Claire and Anthony Tait

Principal Timpani Louise Lewis Goodwin Geoff and Mary Ball

Stephanie Gonley

Kana Kawashima

Siún Milne

Aisling O’Dea

Fiona Alexander

Sarah Bevan-Baker

Catherine James Sian Holding

Marcus Barcham Stevens Gordon Bragg

Rachel Spencer

Hatty Haynes

Niamh Lyons Rachel Smith

Viola Hannah Shaw

Zoë Matthews

Liam Brolly

Rebecca Wexler

Cello

Christian Elliott

Donald Gillan

Eric de Wit

Kim Vaughan Bass

Roberto Carillo-Garcia

Will Duerden

Information correct at the time of going to print

André Cebrián

Lee Holland

Robin Williams

Katherine Bryer

Clarinet Maximiliano Martín

William Stafford Bassoon

Cerys Ambrose-Evans Alison Green

Boštjan Lipovšek

Jamie Shield

Lauren Reeve-Rawlings

Ian Smith

Peter Franks Simon Bird

Timpani Louise Lewis Goodwin

Stephanie Gonley LeaderFarrenc (1804-1875)

Symphony No 3 in G minor (1847)

Adagio – Allegro

Adagio cantabile

Scherzo: Vivace

Finale: Allegro

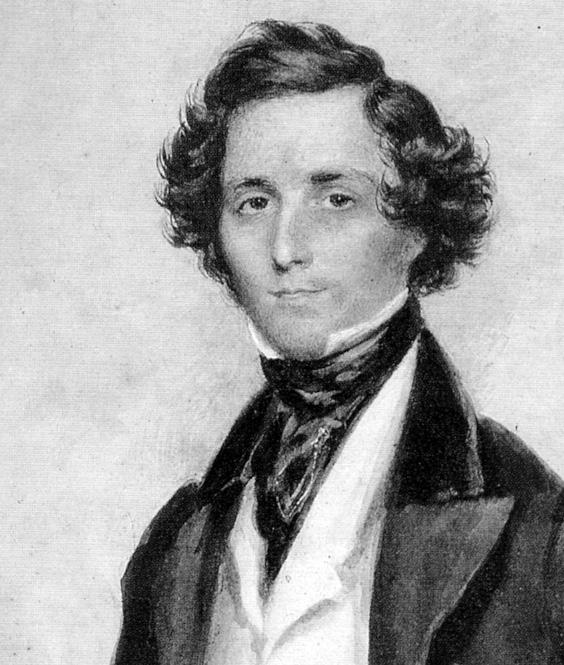

Mendelssohn (1809–1847)

Lieder ohne Worte (1829-45) arr. Tarkmann (2009)

1. Adante con moto (Op 19 No 1)

2. Agitato con fuoco (Op 30 No 4)

3. Allegretto tranquillo, 'Venetianisches Gondellied' (Op 30 No 6)

5. Moderato (Op 67 No 5)

6. Allegretto non troppo, 'Wiegenlied genannt' (Op 67 No 6)

7. Allegro di molto (Op 30 No 2)

Mendelssohn (1809–1847)

Overture, ‘The Hebrides’ (1830, revised 1832)

Schubert (1797-1828)

Symphony No 4 in C minor ‘Tragic’, D 417 (1816)

Adagio molto – Allegro vivace

Andante

Menuetto: Allegro vivace Allegro

Four diverse pieces from three contrasting composers share the stage in tonight’s concert, all written within just a few decades of each other.

We begin with music of great energy, grit and determination. Not for nothing has composer Louise Farrenc been dubbed 'the female Beethoven'. Indeed, her Third Symphony shatters any lazy notions that music by a female composer might be soft, gentle, delicate or elusive.

But we shouldn’t be surprised. So restricted were the possibilities for a woman to achieve success and respect in music in the 19th century, and so formidable were the obstacles to a successful career in the arts, that only women with the strongest selfbelief and determination made it through. Farrenc clearly possessed both of those attributes.

She was born in Paris in 1804, into the influential and artistic Dumont family (her forebears had included painters and sculptors to the royal court stretching back to the 17th century), and her family encouraged her artistic passions right from the start, arranging for her to study with luminaries of the time, including Hummel and Moscheles for piano, and Reicha for composition. It was as a performer at private Parisian soirées that she met her future husband, the composer and flautist Aristide Farrenc, and he further encouraged her in her musical pursuits, as well as introducing her to the wider musical world of Auber and Halévy, Berlioz and Schumann.

With the birth of their daughter Victorine in 1826, Louise decided to end her travelling career as a piano soloist, and to concentrate

instead on teaching and composition. She was taken on as a professor of piano at the Paris Conservatoire in 1842, and quickly became one of Europe’s most prestigious keyboard pedagogues – though she had to tolerate a salary of barely half that of her male colleagues, until she successfully demanded parity.

Ironically, part of Farrenc’s fame and success as a composer came from the fact that she was a woman, and thus attracted large audiences curious to hear her music, listeners who could scarcely believe that these powerful, passionate works had been written by a female musician.

Her Third Symphony is a case in point. It received its premiere in 1849 at the Paris Conservatoire, by the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire under conductor Narcisse Girard, who had been reluctant to

programme her music – and probably tried to rob Farrenc’s new work of the admiration it deserved by programming it alongside Beethoven’s Fifth, then (as now) a muchloved and much-admired musical warhorse.

But no matter: Farrenc’s Third doesn’t need to compete with Beethoven for respect –though it shares with the German composer’s later works a remarkable clarity of thought and directness of utterance, as well as an astonishing concentration of expressive power. Following a sinuous slow introduction, the first movement builds into a swaggering, turbulent faster main section with a dense, compelling argument. It’s followed by a lyrical slow movement that offsets its delicacy with passages of surprising power, and then a scurrying, quicksilver scherzo of a third movement, which wears its indebtedness to Mendelssohn as a badge of honour. Mendelssohn returns, alongside

Sorestrictedwerethe possibilitiesforawoman toachievesuccessand respectinmusicinthe19th century,andsoformidable weretheobstaclestoa successfulcareerinthe arts,thatonlywomenwith thestrongestself-belief anddeterminationmadeit through.Louise Farrenc

WeturntoMendelssohnhimselffortonight’snext collectionofpieces.Andanyonewho’severtakenpiano lessonsmightwellbefamiliarwithMendelssohn’s SongswithoutWords.They’resomethingofastaple forstudentplayers,notdifficultenoughtodemanda virtuosoprofessional,butsufficientlytaxingtodisplay considerable skill and talent.

Schumann, as godfather hovering above Farrenc’s restless, dramatic finale, though its textural inventiveness is all her own.

We turn to Mendelssohn himself for tonight’s next collection of pieces. And anyone who’s ever taken piano lessons might well be familiar with Mendelssohn’s Songs without Words. They’re something of a staple for student players, not difficult enough to demand a virtuoso professional, but sufficiently taxing to display considerable skill and talent. Indeed, Mendelssohn wrote them specifically for domestic consumption, so that talented amateurs would take pleasure from playing to family and friends at home.

And because of that, they’re sometimes rather looked down on as mere educational or amateur pieces, when in fact they’re cunningly crafted miniatures, displaying

Mendelssohn’s compositional prowess at its most disarmingly direct and uncomplicated. And they’re clearly pieces that had a significant personal resonance for the composer: he wrote no fewer than 48 in total, across eight books of six pieces each, between 1829 and 1845. It’s said that Mendelssohn himself invented the form (though it may in fact have been his sister Fanny), taking inspiration from song composers such as Schubert, but assigning what might have been a lyrical vocal melody to the piano’s right hand.

Some speculated that the Songs had originally had words, but Mendelssohn denied it, even expressing outrage when a few brave souls attempted to add the ‘missing’ texts. ‘For my part I do not believe that words suffice for such a task and if they did I would no longer make any music,’ Mendelssohn wrote to a student

in 1842. ‘People usually complain that music is too many-sided in its meanings; what they should think when they hear it is so ambiguous, whereas everyone understands words. For me it is precisely the opposite, not only with entire speeches, but also with individual words. They too seem so ambiguous, so vague, so subject to misunderstanding when compared with true music, which fills the soul with a thousand better things than words.’

It was in 2009 that the German oboist and composer Andreas N Tarkmann arranged a selection of seven of Mendelssohn’s Songs without Words for oboe and string orchestra. The first, with a slow-moving, gently flowing melody against a rippling accompaniment, is the very first Song in the very first book, published in London in 1832. The second shows Mendelssohn at his most volatile, in a whirling dance from the second volume. The third (also from book two), dubbed a ‘Venetian Gondola Song’ by Mendelssohn’s publishers, sets a plaintive melody against an appropriately rocking accompaniment, while the fourth (omitted tonight) is a gentle dance piece from book seven. The fifth is a wistful Song from book six, with a sinuous melody and a folk-like undulating introduction that returns at the end. After the elegant waltz of the sixth Song, also from book six, the seventh – which takes us back to book two –is stormy and driven, bringing the set to an energetic conclusion.

We remain with Mendelssohn for tonight’s next piece, but he’s now a 20-year-old famously embarking on a tour of Scotland. His three-week trip in the summer of 1829 would later produce two of his most renowned pieces of music: tonight’s 'Hebrides' Overture, and also the ‘Scottish’ Symphony.

It was Mendelssohn’s parents who suggested he should travel, and it was young Felix who decided he would begin in England and Scotland (though he toured France and Italy at later occasions in his three-year, stop-start European excursion). And even by today’s standards, it was quite some journey, a tour that was remarkably well captured in Mendelssohn’s letters home and also in his charming sketches of the places he visited.

He arrived in London in April 1829, then travelled north by stagecoach, arriving in Edinburgh on 26 July. There, he lodged in Albany Street, climbed Salisbury Crags and Arthur’s Seat, and contemplated the atmospheric ruins of Holyrood Chapel (which would later inspire the opening of his ‘Scottish’ Symphony). After a side trip to Melrose and Abbotsford, home of Sir Walter Scott, he continued north to Stirling, Perth and Dunkeld, then on further to Killiecrankie, Aberfeldy, Kenmore, Crianlarich, Glencoe, Ballachulish and Fort William. From there he took a steamer down Loch Linnhe to Oban, and continued by water to Tobermory on Mull.

And it was from Tobermory that Mendelssohn sent his famous letter home with 21 bars of what would become the opening of his 'Hebrides' Overture, writing before the musical passage: ‘In order to make you understand how extraordinarily the Hebrides affected me, the following came into my mind there.’ The music that has become indelibly associated with Fingal’s Cave on the isle of Staffa, therefore, was actually begun before Mendelssohn had even set eyes on the place. Perhaps he had another location in mind all along: Mull, after all, is a Hebridean island. But that confusion is mostly down to Mendelssohn’s German publishers, Breitkopf & Härtel, who decided

to publish the finished Overture – four years later, in 1833 – with the title Fingal’s Cave, despite retaining 'The Hebrides' for the orchestral parts. (That surreptitious renaming was probably a selling ploy, since Fingal’s Cave was already a wellknown location through its mythological associations and its mentions in literature.)

Mendelssohn himself struggled over his 'Hebrides' Overture upon his return to Berlin, and indeed originally named it Die einsame Insel (‘The Lonely Island’), arguably referring to any number of islands he would have spotted during his journey. But there can be no question that his visit to Staffa lodged firmly in Mendelssohn’s memory, for all the wrong reasons. Rather than taking the road to Fionnphort, a ferry to Iona, then a smaller boat the short hop north to Staffa, as today’s travellers do, he departed for Staffa from Tobermory, heading north then west straight

into the worst the Atlantic could throw at him. As a result, Mendelssohn was horribly seasick, a state not helped by the stench of oil generated by the steamer on which he travelled. No wonder that, struggling with the Overture, he later wrote to his sister Fanny: ‘I still do not consider it finished. The middle part, forte in D major, is very stupid, and savours more of counterpoint than of oil and seagulls and dead fish, and it ought to be the very reverse.’

Indeed, the rocking rhythms of the sea – for better or worse – can be felt from start to finish of the 'Hebrides' Overture, beginning with the opening’s repeating figures in the low strings, with rising harmonies above hinting at some coming revelation. The broader, more expansive and more obviously lyrical second theme begins similarly in the cellos and bassoons, but, following a development section that builds to what surely represents

Mendelssohn himself struggledoverhis HebridesOvertureupon hisreturntoBerlin,and indeedoriginallynamed itDieeinsameInsel(‘The LonelyIsland’),arguably referringtoanynumber of islands he would have spottedduringhisjourney.Felix Mendelssohn Franz Schubert

Mendelssohn’s memories of the stormy seas, returns in a beautiful moment of true calm on a solo clarinet, before the storm whips up again to finish the Overture.

Tonight’s concert closes with another youthful work: Schubert wrote his Fourth Symphony in 1816, when he was just 19. And while it’s the most serious-minded of the six symphonies he wrote while in his teens and early 20s, its ‘Tragic’ title feels rather like youthful self-dramatising, perhaps to pique the interest of publishers or impresarios.

Schubert composed the Symphony while working as an all-purpose teacher at his father’s school in Vienna, where he was feeling increasingly over-qualified, and nurturing ambitions to write for larger, more professional ensembles than the small amateur orchestra that had grown out of his family’s string quartet. And though

it undoubtedly displays ambition, the Symphony also looks back with fondness to the music of Haydn and Mozart, rather more than to the revolutionary works of Beethoven.

The slow introduction to its first movement seems modelled on the ‘Representation of Chaos’ from Haydn’s Creation, even if the lighter, faster main section that follows is pure Schubert. The bittersweet second movement unexpectedly erupts twice into furious music, but it’s quickly absorbed back into the lyrical mood. Following the third movement Scherzo, the finale plays games with running accompaniment figures, and closes with a return of the Symphony’s opening octaves, now signalling a triumphantly happy ending. Perhaps whatever tragedy there was has dissipated after all.

© David KettleAndthoughitundoubtedly displaysambition,the Symphonyalsolooksback withfondnesstothemusic ofHaydnandMozart, rathermorethantothe revolutionaryworksof Beethoven.

François Leleux – conductor and oboist – is renowned for his irrepressible energy and exuberance. He is currently Artistic Partner of Camerata Salzburg. Leleux was previously Artist-in-Association with Orchestre de Chambre de Paris and has featured as Artist-in-Residence with orchestras such as hr-Sinfonieorchester, Orchestre Philharmonique de Strasbourg, Berner Symphonieorchester, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, and Orquesta Sinfónica de Tenerife.

In the 2022/23 season, Leleux will conduct the Swedish Chamber Orchestra, WDR Sinfonieorchester, Japan Philharmonic Orchestra, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra and Tiroler Symphonieorchester. He has previously conducted orchestras such as Oslo Philharmonic, Orchestre National de Lille and the Sydney, Gulbenkian and Tonkünstler orchestras.

As an oboist Leleux has performed as soloist with orchestras such as New York Philharmonic, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, Budapest Festival Orchestra, and the Swedish Radio and the NHK symphony orchestras. A dedicated chamber musician, he regularly performs worldwide with sextet Les Vents Français and with recital partners Lisa Batiashvili, Eric Le Sage and Emmanuel Strosser.

Committed to expanding the oboe’s repertoire, Leleux has commissioned many new works from composers such as Nicolas Bacri, Michael Jarrell, Giya Kancheli, Thierry Pécou, Gilles Silvestrini and Eric Tanguy. As a conductor, Leleux and the Scottish Chamber Orchestra released an album of works by Bizet and Gounod for Linn Records in 2019.

François Leleux is a Professor at the Hochschule für Musik und Theater München.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

The internationally celebrated Scottish Chamber Orchestra is one of Scotland’s National Performing Companies.

Formed in 1974 and core funded by the Scottish Government, the SCO aims to provide as many opportunities as possible for people to hear great music by touring the length and breadth of Scotland, appearing regularly at major national and international festivals and by touring internationally as proud ambassadors for Scottish cultural excellence.

Making a significant contribution to Scottish life beyond the concert platform, the Orchestra works in schools, universities, colleges, hospitals, care homes, places of work and community centres through its extensive Creative Learning programme. The SCO is also proud to engage with online audiences across the globe via its innovative Digital Season.

An exciting new chapter for the SCO began in September 2019 with the arrival of dynamic young conductor Maxim Emelyanychev as the Orchestra’s Principal Conductor.

The SCO and Emelyanychev released their first album together (Linn Records) in November 2019 to widespread critical acclaim. The repertoire - Schubert’s Symphony No. 9 in C major ‘The Great’ –is the first symphony Emelyanychev performed with the Orchestra in March 2018.

The SCO also has long-standing associations with many eminent guest conductors including Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen, François Leleux, Pekka Kuusisto, Richard Egarr, Andrew Manze and John Storgårds.

The Orchestra enjoys close relationships with many leading composers and has commissioned almost 200 new works, including pieces by the late Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, Sir James MacMillan, Sally Beamish, Martin Suckling, Einojuhani Rautavaara, Karin Rehnqvist, Mark-Anthony Turnage, Nico Muhly, Anna Clyne and Associate Composer Jay Capperauld.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

MÖDER DY / MOTHER WAVE

Part of Celtic Connections 2023

26-27 Jan, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

MOZART’S FLUTE CONCERTO 15-17 Feb, 7.30pm St Andrews | Edinburgh | Glasgow

MAXIM CONDUCTS BRAHMS

23-24 Feb, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

BRAHMS’S CHAMBER

PASSIONS

26 Feb, 3pm Edinburgh THE DREAM Sponsored by Pulsant 2-4 Mar, 7.30pm Perth | Edinburgh | Glasgow

FOLK INSPIRATIONS

WITH PEKKA 9-10 Mar, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

TRANSCENDENTAL VISIONS WITH PEKKA AND SAM 12 Mar, 3pm Edinburgh

LES ILLUMINATIONS

15-17 Mar, 7.30pm St Andrews | Edinburgh | Glasgow

HANDEL: MUSIC FOR THE ROYALS

Our Edinburgh concert is kindly supported by The Usher Family 23-24 Mar, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

SCHUBERT’S

UNFINISHED SYMPHONY

Kindly supported by Claire and Mark Urquhart 30 Mar-1 Apr, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow | Aberdeen

SUMMER NIGHTS

WITH KAREN CARGILL 19-21 Apr, 7.30pm St Andrews | Edinburgh | Glasgow

BEETHOVEN’S FIFTH 27-29 Apr, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow | Aberdeen

TCHAIKOVSKY’S FIFTH 4-5 May, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

BRAHMS REQUIEM 11-12 May, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

4 Royal Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 5AB +44 (0)131 557 6800 sco.org.uk

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra is a charity registered in Scotland No. SC015039. Company registration No. SC075079.

Find us on

Generations of our clients have trusted us to help build and preserve their wealth.

For over 250 years, they have relied on our expert experience to help make sense of a changing world. During that time we’ve earned an enviable reputation for a truly personal approach to managing wealth.

For those with over £250,000 to invest we o er a dedicated investment manager, with a cost structure and level of service, that generates exceptional client loyalty.

Find out more about investing with us today: Murray Clark at our Edinburgh o ce on 0131 221 8500, Gordon Ferguson at our Glasgow o ce on 0141 222 4000 or visit www.quiltercheviot.com

Investors should remember that the value of investments, and the income from them, can go down as well as up and that past performance is no guarantee of future returns. You may not recover what you invest. Quilter Cheviot and Quilter Cheviot Investment Management are trading names of Quilter Cheviot Limited. Quilter Cheviot Limited is registered in England with number 01923571, registered o ce at Senator House, 85 Queen Victoria Street, London, EC4V 4AB. Quilter Cheviot Limited is a member of the London Stock Exchange and authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority.

A warm welcome to everyone who has recently joined our family of donors, and a big thank you to everyone who is helping to secure our future.

Monthly or annual contributions from our donors make a real difference to the SCO’s ability to budget and plan ahead with more confidence. In these extraordinarily challenging times, your support is more valuable than ever.

For more information on how you can become a regular donor, please get in touch with Mary Clayton on 0131 478 8369 or email mary.clayton@sco.org.uk.

The SCO is a charity registered in Scotland No SC015039.