Wednesday

Ives

Raskatov

No 8 in G

Adagio from String

Sospiri, Op

Hall, St Andrews

Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh

Halls, Glasgow

Life of W A Mozart

'Le soir'

Dances from The Soldier's Tale Suite: Tango, Valse, Ragtime Weill Violin Concerto

Stravinsky

Marwood Violin

Royal Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 5AB

(0)131

6800

info@sco.org.uk | sco.org.uk

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra is a

registration No. SC075079.

in Scotland No. SC015039.

The SCO is extremely grateful to the Scottish Government and to the City of Edinburgh Council for their continued support. We are also indebted to our Business Partners, all of the charitable trusts, foundations and lottery funders who support our projects, and to the very many individuals who are kind enough to give us financial support and who enable us to do so much. Each and every donation makes a difference and we truly appreciate it.

Lucinda and Hew Bruce-Gardyne Malcolm and Avril Gourlay James and Felicity Ivory

Christine Lessels

Clair and Vincent Ryan Alan and Sue Warner

Eric G Anderson

David Caldwell in memory of Ann Tom and Alison Cunningham John and Jane Griffiths Judith and David Halkerston

J Douglas Home Audrey Hopkins

David and Elizabeth Hudson Dr and Mrs Peter Jackson

Dr Daniel Lamont Chris and Gill Masters Duncan and Una McGhie Anne-Marie McQueen James F Muirhead Patrick and Susan Prenter Mr and Mrs J Reid Martin and Mairi Ritchie

Elaine Ross

Hilary E Ross

George Rubienski

Jill and Brian Sandford

Michael and Elizabeth Sudlow Robert and Elizabeth Turcan

Tom and Natalie Usher Anny and Bobby White Finlay and Lynn Williamson Ruth Woodburn

Lord Matthew Clarke Caroline Denison-Pender Andrew and Kirsty Desson

David and Sheila Ferrier Chris and Claire Fletcher James Friend Iain Gow Ian Hutton David Kerr Gordon Kirk

Robert Mackay and Philip Whitley Mike and Karen Mair Anne McAlister and Philip Sawyer Gavin McEwan Roy and Svend McEwan-Brown Alan Moat

John and Liz Murphy Alison and Stephen Rawles Andrew Robinson Ian S Swanson John-Paul and Joanna Temperley Anne Usher Catherine Wilson Neil and Philippa Woodcock G M Wright Bruce and Lynda Wyer

Silver

Roy Alexander Joseph I Anderson Pamela Andrews and Alan Norton

Dr Peter Armit William Armstrong Fiona and Neil Ballantyne Timothy Barnes and Janet Sidaway

The Batsleer Family Jack Bogle Jane Borland Michael and Jane Boyle Mary Brady Elizabeth Brittin John Brownlie Laura Buist Robert Burns

Sheila Colvin Lorn and Camilla Cowie Lord and Lady Cullen of Whitekirk Adam and Lesley Cumming Jo and Christine Danbolt Dr Wilma Dickson

James Dunbar-Nasmith Dr and Mrs Alan Falconer Sheila Ferguson Dr James W E Forrester Dr William Fortescue

Jeanette Gilchrist David Gilmour Dr David Grant Margaret Green Andrew Hadden J Martin Haldane Ronnie and Ann Hanna Ruth Hannah Robin Harding Roderick Hart Norman Hazelton Ron and Evelynne Hill Clephane Hume Tim and Anna Ingold David and Pamela Jenkins Catherine Johnstone Julie and Julian Keanie Marty Kehoe Professor Christopher and Mrs Alison Kelnar Dr and Mrs Ian Laing Janey and Barrie Lambie Graham and Elma Leisk Geoff Lewis Dorothy A Lunt Vincent Macaulay Joan MacDonald Isobel and Alan MacGillivary Jo-Anna Marshall

James McClure in memory of Robert Duncan Gavin McCrone Michael McGarvie Brian Miller James and Helen Moir Alistair Montgomerie Margaret Mortimer and Ken Jobling Andrew Murchison Hugh and Gillian Nimmo David and Tanya Parker Hilary and Bruce Patrick Maggie Peatfield John Peutherer in memory of Audrey Peutherer

James S Potter Alastair Reid Fiona Reith Alan Robertson Olivia Robinson Catherine Steel Ian Szymanski Michael and Jane Boyle Douglas and Sandra Tweddle

Margaretha Walker James Wastle C S Weir Bill Welsh

Roderick Wylie

We believe the thrill of live orchestral music should be accessible to everyone, so we aim to keep the price of concert tickets as fair as possible. However, even if a performance were completely sold out, we would not cover the presentation costs.

We are indebted to everyone acknowledged here who gives philanthropic gifts to the SCO of £300 or greater each year, as well as those who prefer to remain anonymous. We are also incredibly thankful to the many individuals not listed who are kind enough to support the Orchestra financially, whether that is regularly or on an ad hoc basis. Every single donation makes a difference and we are truly grateful.

Become a regular donor, from as little as £5 a month, by contacting Mary Clayton on 0131 478 8369 or mary.clayton@sco.org.uk

Our Principal Conductor’s Circle is made up of individuals who share the SCO’s vision to bring the joy of music to as many people as possible. These individuals are a special part of our musical family, and their commitment and generosity benefit us all – musicians, audiences and creative learning participants alike. We would like to extend our grateful thanks to them for playing such a key part in the future of the SCO.

Erik Lars Hansen and Vanessa C L Chang Kenneth and Martha Barker

Creative Learning Fund David and Maria Cumming

Annual Fund

James and Patricia Cook Dr Caroline N Hahn Hedley G Wright

Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen Donald and Louise MacDonald

Chorus Director Gregory Batsleer Anne McFarlane

Viola Steve King Sir Ewan and Lady Brown

Principal Cello Philip Higham The Thomas Family

Cello Donald Gillan Professor Sue Lightman Cello Eric de Wit Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund

Visiting Artists Fund Colin and Sue Buchan Claire and Anthony Tait Anne and Matthew Richards Productions Fund The Usher Family

International Touring Fund Gavin and Kate Gemmell

Principal Second Violin Marcus Barcham Stevens Jo and Alison Elliot

Principal Flute André Cebrián Claire and Mark Urquhart

Principal Oboe Robin Williams Hedley G Wright

Principal Clarinet Maximiliano Martín Stuart and Alison Paul

Principal Timpani Louise Goodwin Geoff and Mary Ball

First Violin

Anthony Marwood

Siún Milne Fiona Alexander Amira Bedrush-McDonald Sarah Bevan-Baker Catherine James Stewart Webster Lorna McLaren

Second Violin Marcus Barcham Stevens Gordon Bragg Michelle Dierx Rachel Smith

Niamh Lyons Feargus Hetherington

Viola Max Mandel Jessica Beeston

Brian Schiele Steve King Cello Philip Higham Su-a Lee Donald Gillan Eric de Wit Bass Nikita Naumov Adrian Bornet Daniel Griffin Yehor Podkolzin

Information correct at the time of going to print

André Cebrián Nicola Crowe Piccolo Nicola Crowe

Oboe Fraser Kelman Katherine Bryer

Clarinet

Maximiliano Martín William Stafford Bassoon Cerys Ambrose-Evans Alison Green

Horn Huw Evans Jamie Shield Trumpet Peter Franks

Trombone Nigel Cox

Timpani Alasdair Kelly Percussion Louise Lewis Goodwin Harp Helen Thomson Harpsichord Andrew Forbes

Nikita Naumov Principal Double Bass

Ives (1874-1954)

The Unanswered Question (1908)

Raskatov (b 1953)

Five Minutes from the Life of W A Mozart (2001)

Haydn (1732-1809)

Symphony No 8 in G ‘Le soir’ (1761)

Allegro molto Andante Menuet & Trio

La tempesta: Presto Bruckner (1824-1896)

String Quintet: Adagio (1878-1879)

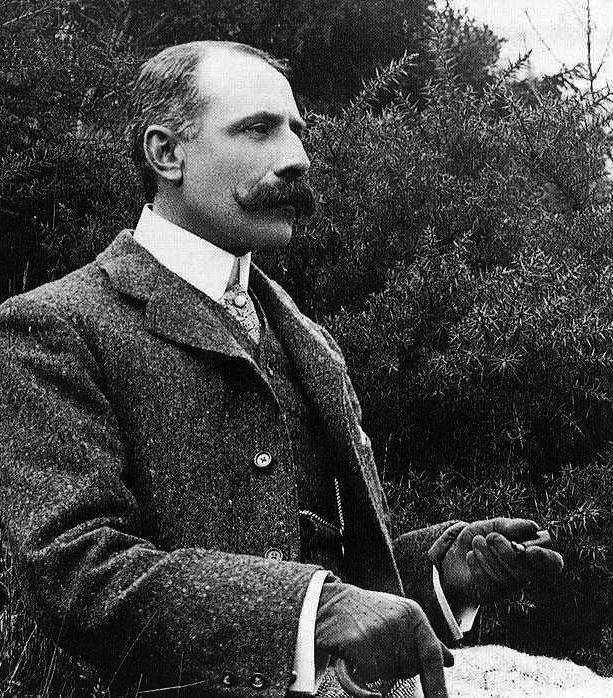

Elgar (1857-1934)

Sospiri Op 70 (1914)

Stravinsky (1882-1971)

Three Dances from The Soldier's Tale Suite (1918)

Tango Valse Ragtime Weill (1900-1950)

Violin Concerto (1924)

I. Andante con moto

IIa. Notturno: Allegro un poco tenuto

IIb. Cadenza: Moderato

IIc. Serenata: Allegretto

III. Allegro molto, un poco agitato

As well as being a compelling collection of contrasting pieces, tonight’s programme is also something of a journey. From darkness to light, as the concert’s title puts it, and also through musical time – from the vast, mysterious expanses of the ancient cosmos to the sophisticated culture of 20th century Europe.

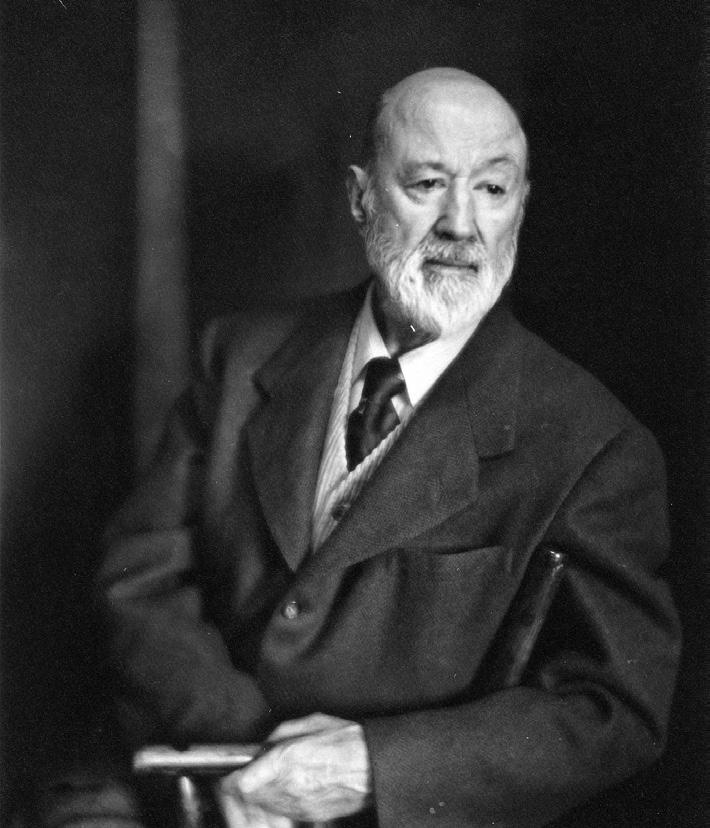

We begin in – well, maybe ancient times, maybe a metaphorical, philosophical alternative reality, but certainly in the darkness of ignorance, and with the biggest question of them all. American maverick and pioneer Charles Ives was decades ahead of his time in his musical thinking, taking inspiration from his US Army bandleader father and the free thinking of New England transcendentalists Emerson and Thoreau to create some of the 20th century’s most forward-looking music. It meant, inevitably, that he was almost entirely disregarded in his own lifetime, but has been understandably lionised in more recent years.

The Unanswered Question, for example, dates from 1908, but wasn’t performed until 1946. Ives originally intended it as one of a duo of pieces he called Two Contemplations, though it’s found a fulfilling life on its own (as has its original partner piece, Central Park in the Dark). And the query it poses is nothing less than, as Ives describes it, the ‘Perennial Question of Existence’. Indeed, the piece is nothing less than a cosmic philosophical drama in music, complete with characters and plot, crammed into a few brief minutes’ duration. Ives himself outlined the storyline and musical actors in his own preface to the score:

‘The strings… represent “The Silences of the Druids – Who Know, See and Hear Nothing”. The trumpet intones “The Perennial Question of Existence”, and states it in the same tone of voice each time. But the hunt for “The Invisible Answer” undertaken by the flutes and other human beings, becomes gradually more active, faster and louder… “The Fighting Answerers”, as the time goes on, and after a “secret conference”, seem to realise a futility, and begin to mock “The Question” – the strife is over for the moment. After they disappear, “The Question” is asked for the last time, and “The Silences” are heard beyond in “Undisturbed Solitude”.’

There’s plenty to ponder in Ives’s philosophical imaginings, but perhaps less that might raise a smile. Any lack of humour is about to be made up for, however, by Moscow-born composer and musical

Charles Edward Ives

Charles Edward Ives

trickster Alexander Raskatov. He was in his late 30s when the Soviet Union collapsed, an event that no doubt exerted a pivotal influence on the still young composer, who moved to Germany in the 1990s, and now lives in Paris. He’s written plenty of serious-minded avant-garde works, but his music is often shot through, too, with a kind of naive, child-like, even absurdist sense of humour. He admitted as much in a 2010 interview, saying: ‘The modern world’s sound environment reminds me of childhood illusions and requires some escape from the limits of serious academic music making.’

And there’s the distinct feeling that we’re not meant to take his Five Minutes from the Life of WAM (playfully subtitled ‘not a “not-turno”’) from 2001 entirely seriously. From the distant tinkling of wind chimes emerges an innocent, elegantly beautiful Mozartean melody on a solo violin – which far more contemporary sounds from skittering violins, halos of harmonics and other percussion constantly threaten to upstage. Raskatov’s sweet, delicate miniature seems to inhabit a precarious world pitched somewhere between affectionate tribute and merciless mockery: which side you come down on, as it disappears in a puff of smoke, is entirely up to you.

There’s plenty of musical wit, too, in the Symphony No 8, ‘Le soir’, by Joseph Haydn – an authentic example of the Classical elegance and refinement that Raskatov has just been reimagining. And though an ‘evening’ symphony might seem to take us not from darkness to light but in the opposite direction, there’s plenty of vivid colour and drama to experience here before the sun sets entirely.

‘Le soir’ was one of the first symphonies that Haydn wrote as an employee of the fabulously wealthy Esterházy family: in 1761, its year of composition, he’d just been taken on as vice-Kapellmeister (or assistant music director), and he’d be promoted to full Kapellmeister five years later, remaining with the family until 1790.

It was Haydn’s boss, Prince Paul Anton Esterházy, who – having a particular liking for music that told a story – suggested that the composer might like to write three symphonies connected with times of the day. The results were No 6 (‘Le matin’), No 7 (‘Le midi’), and tonight’s ‘Le soir’, which were first performed together in a single soirée at Vienna’s Esterházy Palace that same year.

And as a relatively new employee, Haydn took great pains not only to satisfy the Prince’s requests (including the storytelling

Alexander Raskatov Franz Joseph Haydn

aspect, as we’ll see), but also to gain favour with the other court musicians. He looked back in time to the Baroque concerto grosso form, which pits a small instrumental group as joint ‘soloists’ against a larger orchestral backdrop, in order to write music in which individual players could take to the spotlight and show off their talents.

The first movement’s energetic gigue dance takes its bouncy main theme from the aria ‘Je n’aimais pas le tabac beaucoup’ from Gluck’s opera Le diable à quatre, though the orchestra’s solo flute leads the music into darker territory in a brief central development section. The concerto grosso set-up comes into its own in Haydn’s delicate second movement, in which two violins, a cello and a bassoon break free from the rest of the ensemble to do their own thing, passing elegantly decorated melodies back and forth between them,

though the composer also includes a daringly dramatic, angst-ridden central section.

Following the bouncing, energetic minuet and trio of his third movement, it’s in his finale that Haydn plays his storytelling card. Here, he treated his patrons to a musical thunderstorm, complete with surging, stormy figurations, rapid string scrubbing, unexpected contrasts and sudden swerves of direction, with a prominent role for the solo flute. The musical tempest was quite a well-worn idea in instrumental music – just think of the summer storm in Vivaldi’s earlier Four Seasons (and, later, the furious deluge of Beethoven’s ‘Pastoral’ Symphony). Haydn’s, however, is a surprisingly jolly, brief storm, almost as if we’re observing its meteorological firework display from a safe distance.

And as a relatively new employee, Haydn took great pains not only to satisfy the Prince’s requests (including the storytelling aspect, as we’ll see), but also to gain favour with the other court musicians.

We jump forward more than a century from Haydn’s clarity and concision to the lavish opulence of Bruckner for tonight’s next piece. Bruckner is famed (or notorious, depending on your point of view) for his enormous symphonies (and his extensive, seemingly endless revisions of them) that have been famously described as ‘cathedrals in sound’, as much because of Bruckner’s unshakeable faith in his maker as for the music’s own grandeur and majesty.

You’d be forgiven for wondering how such expansive, visionary music might translate into the far more intimate context of chamber music. The answer is that Bruckner’s sole String Quintet, completed in 1879, is an equally mammoth, visionary work, running to around 45 minutes in performance.

And it had a surprisingly protracted genesis. When he was applying to be

certified as a teacher of harmony and counterpoint by the Vienna Conservatoire, Bruckner so impressed the institution’s director, Josef Hellmesberger Sr, with his improvisation skills that the elder man commissioned a string quartet from him on the spot. Bruckner fended off Hellmesberger Sr’s request for 17 years, but eventually wrote what became his String Quintet (with added viola) in 1878-9. And though it was only premiered in 1885, the Quintet quickly became one of the composer’s most popular works, especially its exquisitely beautiful slow movement, which is now most often played as a stand-alone piece. The Adagio revolves around two main themes – a long, slowly descending violin melody, and an upward-moving theme played against pulsing harmonies – that reach a substantial climax after a huge central development section, winding down again

Bruckner so impressed the institution’s director, Josef Hellmesberger Sr, with his improvisation skills that the elder man commissioned a string quartet from him on the spot.Anton Bruckner Edward Elgar

gradually to a calm return from the two opening themes.

We move firmly into the 20th century for tonight’s next piece. Elgar’s final title –meaning ‘sighs’ in Italian – feels entirely appropriate for the short, achingly sad Sospiri that he wrote for strings in 1914. He’d originally considered calling it ‘Soupir d’amour’ (‘sigh of love’) as a follow-up to his enormously popular salon piece Salut d’amour, but in the end decided its music was too serious and intense to be paired with the somewhat lightweight charm of that earlier work. And while it’s never easy to link a piece’s genesis to events happening at the same time, there’s perhaps a sense in which the gathering storm clouds in Europe before the outbreak of World War I may have influenced the sometimes bleak, tragic atmosphere of Sospiri, which received its premiere on 15 August 1914,

just six weeks after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo.

Just the other side of the Great War, Stravinsky found himself in Switzerland, unable to return to his native Russia following the Revolution, and cut off, too, from the substantial income that his grand, glittering earlier music (including the Ballets Russes scores The Firebird and The Rite of Spring) had brought him. His solution was to start all over again, joining two friends he’d made in Switzerland –writer Charles Ferdinand Ramuz and conductor Ernest Ansermet – to concoct a theatre work for miniature forces based on two Faustian Russian tales of a soldier who inadvertently sells his soul to the devil. The music he wrote for The Soldier’s Tale’s seven-piece ensemble is a world away from the opulence of his Ballets Russes scores, focusing on economy, precision, rhythmic

He’doriginallyconsidered

(‘sighoflove’)asafollowuptohisenormously popularsalonpieceSalut d’amour, but in the end decided its music was too serious and intense to be pairedwiththesomewhat lightweightcharmofthat earlier work.

inventiveness and sardonic humour in its piquant harmonies and melodies – all concerns that would dominate Stravinsky’s music across the following decades. Out of necessity, Stravinsky almost singlehandedly created an entirely new form, setting a trend for small-scale ensembles and a new kind of music theatre that would develop and flourish across the 20th and 21st centuries.

Tonight’s three dances – stylised, abstracted, almost cubist reimaginings of popular dances emerging at the time –come from towards the end of the piece, when the Soldier thinks he has the upper hand after getting the Devil blind drunk over a game of cards. He plays the dances on his violin to wake and entertain his beloved Princess. Needless to say, the happiness doesn’t last: the Devil inevitably has the last word.

We close the concert just a few years later, with the young Kurt Weill in 1924, a world away from both Ives’s cosmic speculations and Haydn’s elegant Classicism. We might know Weill best from the dark, sophisticated cabaret of his collaborations with Bertolt Brecht in The Threepenny Opera, The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny and The Seven Deadly Sins (or even from his later American musicals). His Violin Concerto, however, comes from a few years before the fame and notoriety of his stage works.

Weill had formed a close relationship with his teacher in Berlin, Federico Busoni, who had helped him secure early commissions and performances, and had also encouraged Viennese publisher Universal Edition to take him on. Weill was making quite a name for himself, and, in a break from an opera collaboration with German

Igor Stravinskyexpressionist dramatist Georg Kaiser, decided to write a violin concerto – though it would be unlike any heard before. ‘I am working on a concerto for violin and wind orchestra that I hope to finish within two or three weeks,’ he wrote to his publisher. ‘The work is inspired by the idea – one never carried out before – of juxtaposing a single violin with a chorus of winds.’ In the end, Weill added double basses and percussion to his unusual line-up, but the sound world he created remains just as distinctive as his original intentions. And though it might be a struggle to discern the more popular tunefulness of ‘Mack the Knife’ or ‘September Song’ among the Concerto’s more angular, ascerbic language, its sonic character is unmistakably Weillian in its brassy, windy, acidic harmonies.

Busoni became ill while Weill was writing the piece, and died in July 1924, an event

that Weill reflected in the Concerto’s serious-minded, sometimes lamenting first movement, which even quotes the well-known ‘Dies irae’ plainchant melody from the Latin mass for the dead. The Concerto’s second movement is effectively a miniature suite of character pieces, in which the solo violinist is joined by a xylophone (in the ‘Notturno’), then a trumpet (in the ‘Cadenza’), and finally an oboe and flute (in the ‘Serenata’). Weill’s finale is a whirling, exuberant tarantella that sets its soloist considerable technical challenges. There’s a surprisingly still, thoughtful passage with hypnotic timpani strokes towards the middle, before the energy picks up again, propelling the music – and tonight’s darkness-to-light journey – to its blazing conclusion.

© David KettleWeill was making quite a name for himself, and, in a break from an opera collaboration with German expressionist dramatist Georg Kaiser, decided to write a violin concertoKurt Weill

Anthony Marwood enjoys a wide-ranging international career as soloist, director and chamber musician. Recent solo engagements include performances with the Boston Symphony, St Louis Symphony, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, New World Symphony, London Philharmonic, National Orchestra of Spain, Adelaide Symphony and Sydney Symphony. He has worked with conductors such as Valery Gergiev, Sir Andrew Davis, Thomas Søndergård, David Robertson, Gerard Korsten, Ilan Volkov, Jaime Martín and Douglas Boyd.

Many leading composers have written concertos for him, including Thomas Adès, Steven Mackey, Sally Beamish and Samuel Carl Adams. Anthony is a prolific recording artist, and has recorded 50 CDs for the Hyperion label, alongside many recordings for other labels. His next project is to record Elgar’s violin concerto.

He was the violinist of the Florestan Trio for sixteen years and won the Royal Philharmonic Society Instrumentalist Award in 2006.

In April 2022 he returned to the International Musicians’ Seminar at Prussia Cove, Cornwall to teach a week of masterclasses.

As a chamber musician he has a wide circle of regular collaborators including Steven Isserlis, Aleksandar Madžar, Inon Barnatan, Alexander Melnikov, Dénes Várjon and James Crabb.

He was appointed an MBE in the 2018 Queen’s New Year’s Honours List and was made a Fellow of the Guildhall School of Music in 2013.

He uses a bow by Joseph René LaFleur and plays a 1736 Carlo Bergonzi violin, kindly bought by a syndicate of purchasers, and a 2018 violin made by Christian Bayon.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

The internationally celebrated Scottish Chamber Orchestra is one of Scotland’s National Performing Companies.

Formed in 1974 and core funded by the Scottish Government, the SCO aims to provide as many opportunities as possible for people to hear great music by touring the length and breadth of Scotland, appearing regularly at major national and international festivals and by touring internationally as proud ambassadors for Scottish cultural excellence.

Making a significant contribution to Scottish life beyond the concert platform, the Orchestra works in schools, universities, colleges, hospitals, care homes, places of work and community centres through its extensive Creative Learning programme. The SCO is also proud to engage with online audiences across the globe via its innovative Digital Season.

An exciting new chapter for the SCO began in September 2019 with the arrival of dynamic young conductor Maxim Emelyanychev as the Orchestra’s Principal Conductor.

The SCO and Emelyanychev released their first album together (Linn Records) in November 2019 to widespread critical acclaim. The repertoire - Schubert’s Symphony No. 9 in C major ‘The Great’ –is the first symphony Emelyanychev performed with the Orchestra in March 2018.

The SCO also has long-standing associations with many eminent guest conductors including Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen, François Leleux, Pekka Kuusisto, Richard Egarr, Andrew Manze and John Storgårds.

The Orchestra enjoys close relationships with many leading composers and has commissioned almost 200 new works, including pieces by the late Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, Sir James MacMillan, Sally Beamish, Martin Suckling, Einojuhani Rautavaara, Karin Rehnqvist, Mark-Anthony Turnage, Nico Muhly, Anna Clyne and Associate Composer Jay Capperauld..

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

Generations of our clients have trusted us to help build and preserve their wealth.

For over 250 years, they have relied on our expert experience to help make sense of a changing world. During that time we’ve earned an enviable reputation for a truly personal approach to managing wealth.

For those with over £250,000 to invest we o er a dedicated investment manager, with a cost structure and level of service, that generates exceptional client loyalty.

Find out more about investing with us today: Murray Clark at our Edinburgh o ce on 0131 221 8500, Gordon Ferguson at our Glasgow o ce on 0141 222 4000 or visit www.quiltercheviot.com

Investors should remember that the value of investments, and the income from them, can go down as well as up and that past performance is no guarantee of future returns. You may not recover what you invest. Quilter Cheviot and Quilter Cheviot Investment Management are trading names of Quilter Cheviot Limited. Quilter Cheviot Limited is registered in England with number 01923571, registered o ce at Senator House, 85 Queen Victoria Street, London, EC4V 4AB. Quilter Cheviot Limited is a member of the London Stock Exchange and authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority.

A warm welcome to everyone who has recently joined our family of donors, and a big thank you to everyone who is helping to secure our future.

Monthly or annual contributions from our donors make a real difference to the SCO’s ability to budget and plan ahead with more confidence. In these extraordinarily challenging times, your support is more valuable than ever.

For more information on how you can become a regular donor, please get in touch with Mary Clayton on 0131 478 8369 or email mary.clayton@sco.org.uk.

The SCO is a charity registered in Scotland No SC015039.