11 minute read

WHAT YOU ARE ABOUT TO HEAR

Handel (1685-1759)

Coronation Anthem No 1: Zadok The Priest, HWV 258 (1727)

Water Music Suite No 1 in F, HWV 348 (1715)

Ode for the Birthday of Queen Anne: Eternal Source of Light Divine, HWV 74 (1713)

Eternal source of light divine

The day that gave great Anna birth

Let all the wind race with joy

Let flocks and herds their fear forget

Let rolling streams their gladness show

Kind Health descends on downy wings

The day that gave great Anna birth

Let Envy then conceal her head

United nations shall combine

Coronation Anthem No 3:

The King Shall Rejoice, HWV 260 (1727)

Music for the Royal Fireworks, HWV 351 (1749)

Ouverture (Adagio – Allegro – Lentement – Allegro)

Bourrée

La paix (Largo alla Siciliana)

La Réjouissance (Allegro)

Menuet I and II

When tonight’s concert was first conceived and announced – and, very possibly, when you purchased your ticket for it – few can have imagined quite how timely an issue music for the Royal family would be in March 2023. But with the Coronation of King Charles III just six weeks away, we’re reminded again of the crucial role of music in British state occasions – whether to conjure and intensify ceremonial grandeur, or simply for fun, enjoyment and celebration.

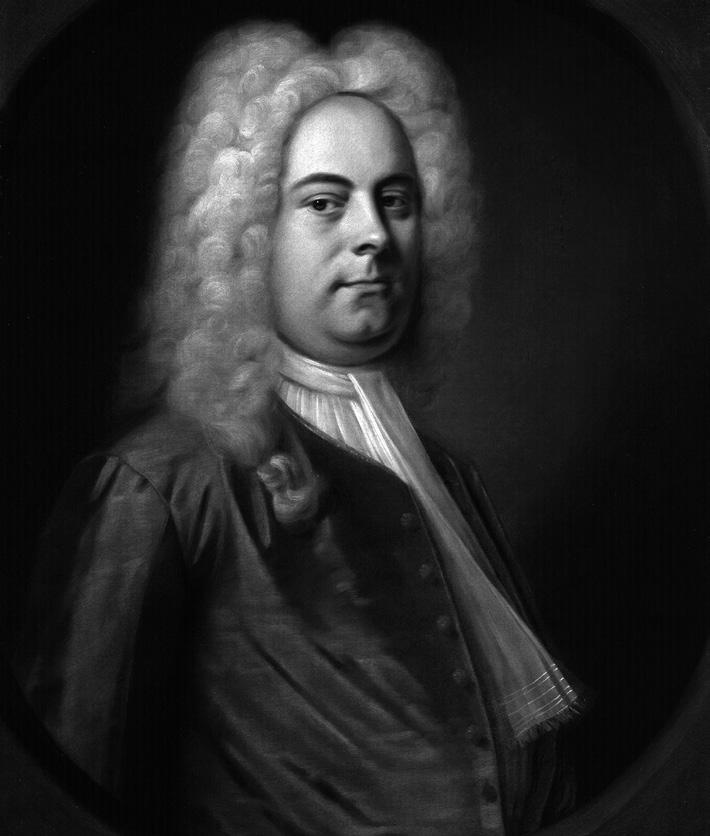

George Frideric Handel, as tonight’s concert demonstrates, proved a master at answering both of those royal requirements, despite never having an official position in the British royal court himself. He was born in Halle, near Leipzig, as Georg Friedrich Händel, and first visited England in the autumn of 1710, where his operas proved so wildly popular that he settled permanently in London just two years later. He’d remain there for the rest of his life, where he’d be appointed a British citizen by King George I in 1727, at which point he adopted the anglicised version of his name we’re more familiar with today. His years in England spanned the reigns of three British monarchs, and Handel wrote music for all of them.

And, since tonight’s concert follows musical rather than chronological logic (this is, after all, a cultural rather than an academic experience), we begin with the last of those monarchs. King George II took the British throne in June 1727, following the death of his father George I, and he personally commissioned Handel to compose music for his Coronation service, which took place on 11 October 1727 in Westminster Abbey. And – as some of the musicians commissioned for our own upcoming Coronation have also observed – that imminent and immovable deadline required some fast work. Handel put his four Coronation Anthems together in the space of only about two weeks, though in the end he could have taken an additional week since the Coronation was postponed after fears that the River Thames might flood.

Despite his tight deadline, however, Handel’s music proved immediately popular, and ideally suited to the occasion. It was a popularity helped, no doubt, by the extravagant performing forces that the composer was able to draw on, which set the crack Choir of the Chapel Royal against an orchestra thought to have numbered between 150 and 200 players. (It’s not clear, in fact, how the singers would even have made themselves heard above such an enormous band of instrumentalists – one possible reason for the description from Archbishop of Canterbury William Wake of

‘the anthem all in confusion: all irregular in the music’.)

Handel composed four Coronation Anthems in all, and tonight we’ll hear two, beginning with by far the most famous. ‘Zadok the Priest’, which takes its text from the Biblical Book of Kings, has been heard at every single British coronation since Handel composed it, and it’s not hard to understand why. With its slow, steady build-up from an orchestral wall of sound before the choir’s blazing initial entry, the Anthem draws clearly on Handel’s extensive expertise in the theatre, ratcheting up tension before releasing it in the far jauntier and more joyful ‘And all the people rejoic’d’ and the vocal and instrumental fireworks of the closing ‘God Save the King’.

We leap back in time to the summer of 1717 – and to George II’s father, George I – for tonight’s next piece. In fact, Handel and the elder George knew each other well. It was George, as Elector of Hanover, who gave Handel one of his first jobs, as music director at his Saxon court, and even put up with the musician’s incessant travels across the Channel for engagements in London. Handel left George’s employment after just a few months – it’s unclear whether he jumped or was pushed – but when the Elector assumed the British throne in 1714, any animosity was quickly put aside, and Handel became a valued musical collaborator.

Musical water excursions were all the rage among Europe’s royalty and super-rich at the time: there was something of a craze for river trips with accompaniments from live musicians, and even for mock naval battles enacted for entertainment purposes. Most vividly remembered of all of them, however, is the trip aboard the Royal Barge that King George I and his retinue undertook on the evening of 17 July 1717, departing from the Palace of Whitehall, arriving for dinner in Chelsea, and then returning again. It wasn’t just the King and his company that were out on the river that evening: many Londoners were intent on joining the festivities, to the extent that the Daily Courant reported that ‘many other Barges with Persons of Quality attended, and so great a Number of Boats, that the whole River in a manner was cover’d’. And for this grand occasion, the King had asked Handel to supply the music.

Let’s return to the Daily Courant for a description of the evening: ‘A City Company’s Barge was employ'd for the Musick, wherein were 50 instruments of all sorts, who play’d all the Way from Lambeth the finest Symphonies, compos’d express for this Occasion, by Mr Hendel; which his Majesty liked so well, that he caus’d it to be plaid over three times in going and returning. At Eleven his Majesty went a-shore at Chelsea where a Supper was prepar’d, and then there was another very fine Consort of Musick, which lasted till 2; after which, his Majesty came again into his Barge, and return’d the same Way, the Musick continuing to play till he landed.’

Handel composed three Water Music suites for the occasion. It was long assumed that they’d been separated between outgoing journey, meal and return, though it’s now thought that all three were probably played at all three stages. However the music’s scheduling worked, tonight’s Suite No 1 would have kicked off the celebrations, and Handel ensured a rich and diverse collection of dances and other pieces to entertain and captivate his royal listeners. The opening Overture contrasts a stately, ceremonial opening with a far jollier, faster section, and it’s followed by a thoughtful oboe aria, and then a sonorous and celebratory Allegro with prominent horns. A gently flowing Andante opens a short set of dances, leading to a livelier, three-time Allegro, a gently moving Air, a brisk and bracing Minuet, a quietly bustling Bourrée and a striding Hornpipe. Handel brings the Suite to a calm, considered conclusion with a graceful Allegro moderato.

If King George I’s 1717 river excursion was a resounding success, his son George II’s pyrotechnic extravaganza on 27 April 1749 was a bit of a fiasco. There’s no questioning its good intentions, however: to celebrate the end of the eight-year War of the Austrian Succession, the King planned a huge firework show in Green Park, for which Handel would supply the music. And for the event, the King had also commissioned Franco-Italian architect Giovanni Niccolò Servandoni to create a vast temporary pavilion, which Servandoni dubbed a ‘Machine’, that would be decorated with sculptures, artifical flowers, statues and allegorical pictures, and serve both as a stage for Handel’s musicians and a launchpad for some of the evening’s pyrotechnics. (You might already see where this is going.)

Things started badly even at the planning stage, when Handel was informed that the King wanted ‘no fiddles’, despite his own intention to use stringed instruments. The composer reluctantly agreed, but rescored his original wind, brass and percussion music to incorporate strings for a later performance. A full rehearsal was announced for 21 April, but not, as expected, in Green Park. Instead, the runthrough happened south of the Thames in

Vauxhall Gardens, and the 12,000 people who attended caused a three-hour carriage jam on London Bridge, the only way for vehicles to cross the River.

When the evening itself arrived, it rained. Many of the show’s estimated 10,000 fireworks failed to ignite, others went astray, and Servandoni’s ‘Machine’ itself caught fire. The architect was so outraged that he pulled his sword on one of the King’s representatives, was promptly arrested, and only released the following day after making a grovelling apology for his behaviour. The writer Horace Walpole neatly summed up the rather anticlimactic nature of the evening: the ‘pitiful and ill-conducted’ event had ‘by no means answered the expense, the length of preparation, and the expectation that had been raised,’ he noted. But it wasn’t all gloom: he also observed that ‘very little mischief was done, and but two persons killed’. Thank goodness for silver linings.

There was no doubt, however, about the grandeur and magnificence of the sixmovement suite that Handel had written for the occasion, combining popular dances with more thoughtful movements marking the event’s purpose. A ceremonial slow introduction launches the opening Ouverture, before its rushing, faster section with quickfire exchanges between brass and strings, and it’s followed by an agile Bourrée that again hops between orchestral groups. The slower, gently rocking ‘La paix’ (or ‘Peace’) reflects the fireworks’ celebration of the end of war, while ‘La réjouissance’ (or ‘Rejoicing’) lives up to its title with loud, confident music that barely seems able to contain its excitement. Handel rounds things off with two lively minuets, the first stomping with rather heavy feet, the second far more buoyant.

This brings us to the earliest music in tonight’s programme. When Handel first settled in London in 1712, Queen Anne was on the British throne, and would remain there for two more years. Her musical interests, however, were far from clear. The Duke of Manchester famously described the Queen as being ‘too careless or too busy to listen to her own band, and had no thought of hearing and paying new players however great their genius or vast their skill’.

There’s some doubt, therefore, whether Queen Anne ever actually heard the Ode that Handel wrote for her birthday in 1713 – or, indeed, whether the piece was even performed on that occasion, which fell on 6 February. It’s not clear, either, how Handel ended up writing the piece in the first place: John Eccles was the Master of the Queen’s Music at the time, but had clearly been overlooked in favour of this German newcomer who was so wildly captivating London audiences with his operas.

What’s beyond doubt is the sheer quality and inventiveness of this nine-movement cantata from Handel’s first years in England. It sets a text by Ambrose Philips that not only marks the monarch’s birthday, but also praises her as a pivotal peacemaker in the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht, and the resolution of the War of the Spanish Succession. Its opening ‘Eternal source of light divine’ is a sublime, contemplative, somewhat otherworldly movement in which the orchestral trumpet mirrors the countertenor’s vocal line, while ‘The day that gave great Anna birth’ shifts us into bustling, good-natured joy, with trumpet and oboe copying the countertenor’s virtuosic figurations. Gusts of gentle breeze from the oboes and violins accompany angels joining the birthday celebrations in ‘Let the winged race with joy’, while ‘Let flocks and herds their fear forget’ is a jolly, bucolic dance.

Countertenor and bass singers playfully depict the very brooks they’re describing in ‘Let rolling streams their gladness show’, while ‘Kind health descends’ is a gentle, pastoral duet for soprano and countertenor. There’s an undeniable grandeur to the choral ‘The day that gave great Anna birth’, and a larger-than-life exuberance to the bass solo ‘Let envy then conceal her head’. Handel brings his Ode to a resplendent conclusion with the bustling vigour of ‘United nations shall combine’, complete with an echo chorus copying the main band of singers.

We finish back where we started, with the Coronation of George II. ‘The King shall Rejoice’, using a text from Psalm 21, was performed at the actual moment of George II’s crowning, using appropriately celebratory, majestic music. Handel sets each of the text’s four lines in a separate, distinctive musical section. The opening ‘The King shall Rejoice’ is brisk and confident, full of ceremonial fanfares, while ‘Exceeding glad shall he be’ is quieter and more playful, with dancelike figures in the strings and lilting vocal lines. ‘Glory and great worship’ stands as a brief, dramatic interlude before the closing ‘Thou has prevented him’, a grand fugue that slowly expands across instruments and voices as Handel displays his compositional prowess. It only needs the intricate ‘Alleluia’ to round the Anthem off majestically.

© David Kettle

Handel (1685-1759)

Coronation Anthem No 1: Zadok The Priest (1727)

Zadok, the priest, and Nathan, the Prophet, anointed Solomon King; and all the people rejoiced, and said:

God save the King, long live the King, may the King live for ever! Amen! Alleluia!

Handel (1685-1759)

Ode for the Birthday of Queen Anne: Eternal Source of Light Divine (1713)

Ode for the birthday of Queen Anne

1. Arioso (Countertenor)

Eternal source of light divine with double warmth thy beams display, and with distinguish'd glory shine, to add a lustre to this day.

2. Aria (Countertenor) & Chorus

The day that gave great Anna birth who fix'd a lasting peace on earth.

3. Aria (Soprano) & Chorus

Let all the winged race with joy their wonted homage sweetly pay, whilst tow'ring in the azure sky they celebrate this happy day: The day that gave great Anna birth who fix'd a lasting peace on earth.

4. Duet (Soprano & Countertenor) & Chorus

Let flocks and herds their fear forget, lions and wolves refuse their prey, and all in friendly consort meet, made glad by this propitious day. The day that gave great Anna birth who fix'd a lasting peace on earth.

5. Duet (Countertenor & Bass) & Chorus

Let rolling streams their gladness show with gentle murmurs whilst they play, and in their wild meanders flow, rejoicing in this blessed day.

The day that gave great Anna birth who fix'd a lasting peace on earth.

6. Duet (Soprano & Countertenor) & Chorus

Kind Health descends on downy wings; angels conduct her on the way. To our glorious Queen new life she brings, and swells our joys upon this day.

7. Duet (Soprano & Countertenor) & Chorus

The day that gave great Anna birth who fix'd a lasting peace on earth.

8. Aria (Bass) & Chorus

Let Envy then conceal her head, and blasted faction glide away. No more her hissing tongues we'll dread, secure in this auspicious day. The day that gave great Anna birth who fix'd a lasting peace on earth.

9. Aria (Countertenor) & Chorus

United nations shall combine, to distant climes the sound convey that Anna's actions are divine, and this the most important day! The day that gave great Anna birth who fix'd a lasting peace on earth.

Handel (1685-1759)

Coronation Anthem No. 3: The King Shall Rejoice (1727)

The King shall rejoice in thy strength, O Lord.

Exceeding glad shall he be of thy salvation.

Glory and great worship hast thou laid upon him.

Thou hast prevented him with the blessings of goodness and hast set a crown of pure gold upon his head.

Alleluia.