MAXIM’S BAROQUE INSPIRATIONS

Kindly supported by Donald and Louise MacDonald

Thursday 24 November, 7.30pm The Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh Friday 25 November, 7.30pm City Halls, Glasgow Saturday 26 November, 7.30pm Aberdeen Music Hall

Grieg Holberg Suite Escaich Baroque Song Górecki Harpsichord Concerto

Interval of 20 minutes

Vivaldi Concerto for 4 Violins and Violoncello, Op 3 No 10, RV 580

Hindemith Suite französischer Tänze

Vivaldi Concerto con molti strumenti, RV 558

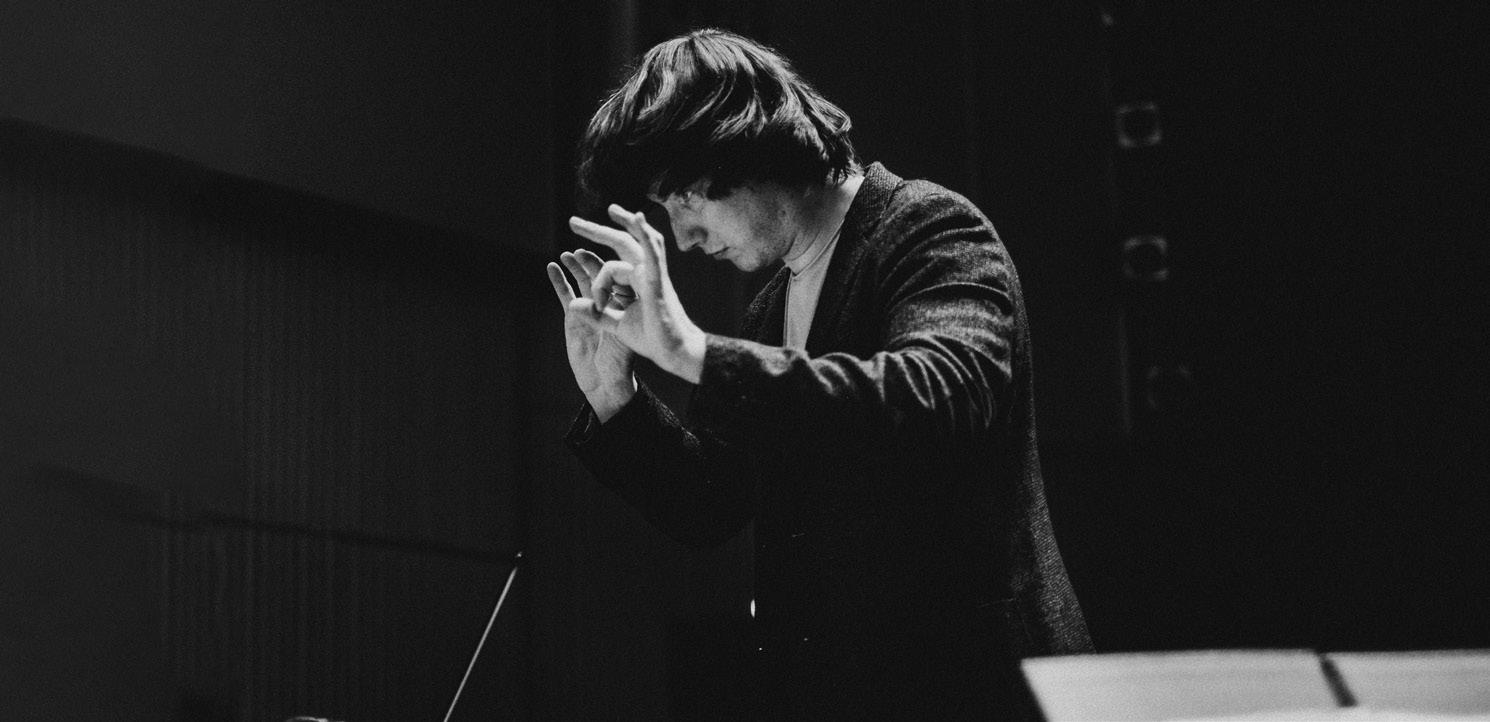

Maxim Emelyanychev Conductor / Harpsichord

Maxim Emelyanychev

4 Royal Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 5AB +44 (0)131 557 6800 | info@sco.org.uk | sco.org.uk

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra is a charity registered in Scotland No. SC015039. Company registration No. SC075079.

The SCO is extremely grateful to the Scottish Government and to the City of Edinburgh Council for their continued support. We are also indebted to our Business Partners, all of the charitable trusts, foundations and lottery funders who support our projects, and to the very many individuals who are kind enough to give us financial support and who enable us to do so much. Each and every donation makes a difference and we truly appreciate it.

Delivered by

Delivered by

Lucinda and Hew Bruce-Gardyne Malcolm and Avril Gourlay

James and Felicity Ivory

Christine Lessels

Clair and Vincent Ryan Alan and Sue Warner

Eric G Anderson

David Caldwell in memory of Ann Tom and Alison Cunningham

John and Jane Griffiths

Judith and David Halkerston

J Douglas Home Audrey Hopkins

David and Elizabeth Hudson Dr and Mrs Peter Jackson Dr Daniel Lamont Chris and Gill Masters Duncan and Una McGhie Anne-Marie McQueen James F Muirhead

Patrick and Susan Prenter

Mr and Mrs J Reid

Martin and Mairi Ritchie

Elaine Ross

Hilary E Ross

George Rubienski

Jill and Brian Sandford

Michael and Elizabeth Sudlow

Robert and Elizabeth Turcan

Tom and Natalie Usher

Anny and Bobby White Finlay and Lynn Williamson

Ruth Woodburn

Lord Matthew Clarke James and Caroline Denison-Pender Andrew and Kirsty Desson David and Sheila Ferrier Chris and Claire Fletcher James Friend

Iain Gow Ian Hutton

David Kerr

Gordon Kirk

Robert Mackay and Philip Whitley Mike and Karen Mair Anne McAlister and Philip Sawyer Gavin McEwan Roy and Svend McEwan-Brown Alan Moat

John and Liz Murphy Alison and Stephen Rawles Andrew Robinson Ian S Swanson

John-Paul and Joanna Temperley Anne Usher

Catherine Wilson Neil and Philippa Woodcock G M Wright

Bruce and Lynda Wyer

Roy Alexander

Joseph I Anderson

Pamela Andrews and Alan Norton

Dr Peter Armit

William Armstrong Fiona and Neil Ballantyne

Timothy Barnes and Janet Sidaway

The Batsleer Family

Jack Bogle

Jane Borland

Michael and Jane Boyle Mary Brady

Elizabeth Brittin

John Brownlie

Laura Buist

Robert Burns

Sheila Colvin

Lorn and Camilla Cowie

Lord and Lady Cullen of Whitekirk Adam and Lesley Cumming Jo and Christine Danbolt

Dr Wilma Dickson

James Dunbar-Nasmith Dr and Mrs Alan Falconer Sheila Ferguson

Dr James W E Forrester Dr William Fortescue

Jeanette Gilchrist

David Gilmour

Dr David Grant Margaret Green Andrew Hadden

J Martin Haldane Ronnie and Ann Hanna Ruth Hannah Robin Harding Roderick Hart Norman Hazelton Ron and Evelynne Hill Clephane Hume Tim and Anna Ingold David and Pamela Jenkins Catherine Johnstone Julie and Julian Keanie Marty Kehoe Professor Christopher and Mrs Alison Kelnar Dr and Mrs Ian Laing Janey and Barrie Lambie Graham and Elma Leisk Geoff Lewis Dorothy A Lunt Vincent Macaulay Joan MacDonald Isobel and Alan MacGillivary Jo-Anna Marshall

James McClure in memory of Robert Duncan Gavin McCrone Michael McGarvie Brian Miller James and Helen Moir Alistair Montgomerie Margaret Mortimer and Ken Jobling Andrew Murchison Hugh and Gillian Nimmo David and Tanya Parker Hilary and Bruce Patrick Maggie Peatfield John Peutherer in memory of Audrey Peutherer

James S Potter Alastair Reid Fiona Reith Alan Robertson Olivia Robinson Catherine Steel Ian Szymanski Michael and Jane Boyle Douglas and Sandra Tweddle Margaretha Walker James Wastle C S Weir Bill Welsh Roderick Wylie

We believe the thrill of live orchestral music should be accessible to everyone, so we aim to keep the price of concert tickets as fair as possible. However, even if a performance were completely sold out, we would not cover the presentation costs.

We are indebted to everyone acknowledged here who gives philanthropic gifts to the SCO of £300 or greater each year, as well as those who prefer to remain anonymous. We are also incredibly thankful to the many individuals not listed who are kind enough to support the Orchestra financially, whether that is regularly or on an ad hoc basis. Every single donation makes a difference and we are truly grateful.

Become a regular donor, from as little as £5 a month, by contacting Mary Clayton on 0131 478 8369 or mary.clayton@sco.org.uk

Our Principal Conductor’s Circle is made up of individuals who share the SCO’s vision to bring the joy of music to as many people as possible. These individuals are a special part of our musical family, and their commitment and generosity benefit us all – musicians, audiences and creative learning participants alike. We would like to extend our grateful thanks to them for playing such a key part in the future of the SCO.

American Development Fund

Erik Lars Hansen and Vanessa C L Chang Kenneth and Martha Barker

Creative Learning Fund David and Maria Cumming

Annual Fund James and Patricia Cook Dr Caroline N Hahn Hedley G Wright

Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen

Donald and Louise MacDonald

Chorus Director Gregory Batsleer Anne McFarlane

Viola Steve King Sir Ewan and Lady Brown

Principal Cello Philip Higham The Thomas Family

Cello Donald Gillan

Professor Sue Lightman Cello Eric de Wit Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund

Visiting Artists Fund

Colin and Sue Buchan Anne and Matthew Richards Productions Fund The Usher Family

International Touring Fund Gavin and Kate Gemmell

Principal Second Violin Marcus Barcham Stevens Jo and Alison Elliot

Principal Flute André Cebrián Claire and Mark Urquhart

Principal Oboe Robin Williams Hedley G Wright

Principal Clarinet Maximiliano Martín Stuart and Alison Paul

Principal Bassoon Cerys Ambrose-Evans Claire and Anthony Tait

Principal Timpani Louise Lewis Goodwin Geoff and Mary Ball

Michael Gurevich

Kana Kawashima Bas Treub

Aisling O’Dea Siún Milne

Amira Bedrush-McDonald Sarah Bevan-Baker

Marcus Barcham Stevens

Gordon Bragg Rachel Spencer

Siobhan Doyle Niamh Lyons Rachel Smith Kristin Deeken Viola Max Mandel Jessica Beeston

Brian Schiele Steve King Cello

Philip Higham Su-a Lee Donald Gillan Eric de Wit Bass

Nikita Naumov Louis van der Mespel

André Cebrián

Adam Richardson

László Rózsa

Francisco Izquierdo Oboe Robin Williams Katherine Bryer

Cor Anglais Katherine Bryer

Clarinet/ Chalumeau Katherine Spencer William Stafford

Information correct at the time of going to print

Horn

Antonio Lagares

Jamie Shield

Trumpet Peter Franks Shaun Harrold

Timpani Louise Lewis Goodwin

Theorbo/ Lute Kristiina Watts Jens Franke

Mandolin Jamie Akers Andrew Maginley

Bassoon Cerys Ambrose-Evans Alison Green

Contrabassoon Alison Green

Philip Higham

Principal Cello

Grieg (1843-1907)

Holberg Suite (1884)

Praeludium: Allegro vivace Sarabande: Andante

Gavotte: Allegretto

Air: Andante religioso Rigaudon: Allegro con brio

Escaich (b. 1965)

Baroque Song (2007)

Vivacissimo Andante

Allegro molto energico

Górecki (1933 - 2010)

Harpsichord Concerto (1980)

Allegro molto Vivace

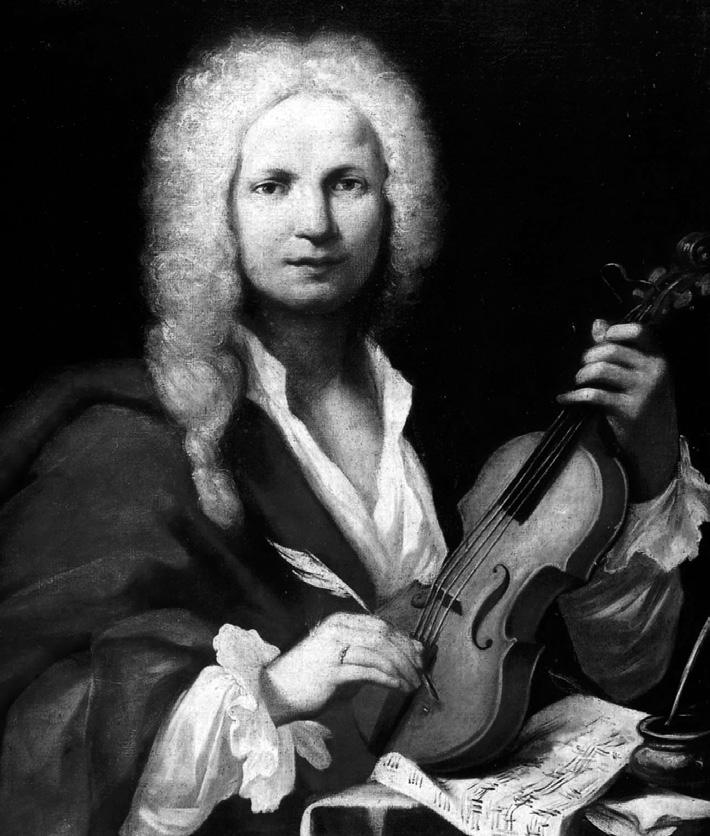

Vivaldi (1678-1741)

Concerto for 4 Violins and Violoncello, Op 3 No 10, RV 580 (1711) Allegro Largo – Larghetto Allegro

Hindemith (1895–1963)

Suite französischer Tänze (1948)

Pavane und Gaillarde (Estienne du Tertre) Tourdion "C'est grand plaisir" Bransle simple Bransle de Bourgogne (Claude Gervaise) Bransle simple (Claude Gervaise) Bransle d'Escosse (Estienne du Tertre) Pavane, wie am Anfang

Vivaldi (1678-1741)

Concerto con molti strumenti, RV 558 (1740)

Allegro molto Andante molto Allegro

There’s a long and rich history of composers gazing backwards in time to their musical forebears for inspiration. JS Bach drew on ancient plainchant melodies, or reimagined earlier concertos by his Italian contemporary Antonio Vivaldi for German listeners (as we’ll discover). The following century, Felix Mendelssohn paid homage to his beloved Bach in works such as the ‘Reformation’ Symphony. And, to bring things right up to date (and full circle), British experimentalist Max Richter has even ‘recomposed’ Vivaldi’s Four Seasons for a 21st-century audience.

It’s inevitable that composers will learn from and build on the great music that has gone before them, usually with respect, sometimes with a healthy dose of scepticism, even subversiveness. But it’s also an approach that became particularly prominent in the 20th century, as composers sometimes looked back longingly to the simplicity and clarity of earlier music in the aftermath of the gargantuan opulence of Mahler, Schoenberg, Richard Strauss and others, or maybe even searched for musical certainty as musical styles and opinions fractured into countless competing threads around them.

For the first piece in tonight’s concert, however, we begin a little earlier – in 1884, when Edvard Grieg completed From Holberg’s Time, now more commonly known simply as the Holberg Suite. Ludvig Holberg was a remarkable figure – a Danish-Norwegian historian, scientist, philosopher and violinist, dubbed the ‘Molière of the north’ because of the popular success of his stage comedies.

Like Grieg, Holberg was born in Bergen, and when the Norwegian city launched its plans to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the great man’s birth in 1884, Grieg was one of several Scandinavian composers commissioned to write music for the event.

Ironically, the main piece he was asked to compose – a male-voice Holberg Cantata

It’s inevitable that composers will learn from and build on the great music that has gone before them, usually with respect, sometimes with a healthy dose of scepticism, even subversiveness.Edvard Grieg

The movements of the Holberg Suite look back to the music of his own times that Holberg would have undoubtedly known – by Bach, Handel and Scarlatti, for example – and combine the energy and elegance of Baroque dance forms with the unmistakable folkinspired twang of Grieg’s own musical language.

for outdoor performance (which duly took place even in the anniversary celebrations’ dark and stormy weather) – has fallen into almost total obscurity. But a set of short, Holberg-inspired piano pieces that Grieg wrote as a distraction from the hard work of the cantata took off immediately, proving such a success that the composer later rescored them for string orchestra.

The movements of the Holberg Suite look back to the music of his own times that Holberg would have undoubtedly known – by Bach, Handel and Scarlatti, for example – and combine the energy and elegance of Baroque dance forms with the unmistakable folk-inspired twang of Grieg’s own musical language. After the brisk, toccata-like Praeludium, the more stately Sarabande has folksy melodies for violins and a solo cello. The stomping dance of the perky Gavotte has a distinctive central

musette over a bagpipe-like drone, and following the solemn song of the Air, the boisterous Rigaudon has a duet for violin and viola that sounds as if Bach were trying out some traditional Norwegian fiddling.

We leap forward in time to 2007 for tonight’s next piece, though it’s to a composer whose particular blend of activities has its own noble heritage. Thierry Escaich stands in a long line of eminent French organist/composers that takes in Widor, Vierne, Dupré, Fauré and Messiaen, among many others, and as organist at Paris’s St-Étienne-du-Mont church, Escaich is himself the direct successor to Maurice Duruflé. It’s probably little surprise, then, that Escaich should be so familiar with the organ music of Bach, and it’s specifically from Bach’s organ chorale preludes that he drew inspiration for his Baroque Song for orchestra.

Rather than direct quotation, however, Escaich’s references to Bach in the piece are more like half-remembered melodies heard in the distant past, older music floating elusively out of reach, largely obscured by Escaich’s own 21st-century creativity. Baroque Song’s first movement begins with a propulsive, Baroque-style figure that’s passed back and forth between instruments (based specifically on Bach’s chorale prelude ‘Nun freut euch, lieben Christen g’mein’, BWV 734). But the familiar-sounding figurations are quickly invaded and transformed by more unusual sonic elements, until you can hardly tell the two apart. Escaich’s longer, slower, dreamier second movement is Baroque Song’s dark heart, colliding together a distant memory of the Bach chorale ‘Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland’, BWV 659, with snaking melodies that might seem more at home in one of Bach’s passions.

A solo cello recitative emerges from the musical destruction that the two elements wreak, leading directly into the fantastical, somewhat grotesque dance of the brief closing movement.

We remain in recent times for tonight’s next piece, which spins something decidedly modern from centuries-old techniques. Polish composer Henryk Górecki established his international reputation in the early 1990s, when a recording of his slow, mournful Third Symphony (named the ‘Symphony of Sorrowful Songs’) of 1976 became a worldwide sensation. His snappy, sparkling Harpsichord Concerto, written four years later and cast in two fast, vigorous movements, is a world away from the sombre Symphony, but like it, manages to wring maximum emotional effect from the most minimal means.

Thierry Escaich

Henryk Mikołaj Górecki

Thierry Escaich

Henryk Mikołaj Górecki

In the case of the Concerto, those means are constant movement, unashamed repetition, relentless melodic figures and unstoppable motor rhythms. The piece’s idiosyncratic tone confounded critics at its 1980 premiere, but the composer signalled that we perhaps shouldn’t take the work too seriously, even referring to it as a ‘prank’.

In the first movement, Górecki seems to be looking back to the showy virtuosity of Baroque toccata forms, with a slowmoving unison string melody accompanied by ceaseless, fast-moving harpsichord ornamentation, each new phrase heralded by a sweeping flourish from the soloist. In the raucous, dance-like second movement, which follows without a pause, a jaunty melody is passed back and forth between harpsichord and strings in incessant quavers and a bright D major tonality, contrasting with far more dissonant harmonies later on.

After a remarkable section where the strings repeat virtually the same chord for more than 100 bars, a fleeting reference to the opening movement signals the Concerto’s abrupt final cadence.

Antonio Vivaldi, of course, lived three centuries ago, and therefore offers the kind of clarity, directness and rhythmic drive that some of the later composers in today’s concert were attempting to emulate, or at least reimagine. In tonight’s two Vivaldi concertos, however, we find the composer on particularly exuberant form, creating music that showcases the skills of a gathering of soloists together.

L’estro armonico (usually translated as ‘Harmonic Fancy’) was Vivaldi’s first published set of concertos, but with its daring orchestrations, striking textures and propulsive rhythms, it made the composer’s

Antonio Vivaldi, of course, lived three centuries ago, and therefore offers the kind of clarity, directness and rhythmic drive that some of the later composers in today’s concert were attempting to emulate, or at least reimagine.Antonio Vivaldi

name thoughout Europe. Demand was so high that following its 1711 publication in Amsterdam, it was reprinted in London and Paris, and even the great JS Bach reworked the B minor work heard tonight as a concerto for four harpsichords and strings, so that he and his sons could play it in their Leipzig coffee-house concerts.

The 12-concerto set was probably written for performance at the Ospedale della Pietà, the Venetian school for orphaned and illegitimate girls where Vivaldi taught from 1703 to 1725. This tenth concerto is written for the unusual combination of four solo violins, solo cello, strings and continuo, and is in three short movements. The opening Allegro unusually begins with a striking dialogue between the soloists rather than with the full orchestra. An extraordinary Larghetto passage in the middle of the slow movement calls upon the four violin soloists

Hindemith

to use four contrasting arpeggio techniques, creating a glistening texture that calls to mind the icy imaginings of ‘Winter’ from The Four Seasons, before Vivaldi’s dancing final Allegro.

For tonight’s final ‘modern’ piece, we join Paul Hindemith – bad boy of German music, who shocked Berlin audiences with his subversive, satirical wit in the 1920s – in Connecticut in 1948, where he’d earlier fled the Nazis to teach at Yale University. It was for Yale music students that he wrote his Suite of French Dances, reconfiguring dance tunes by Claude Gervaise and Estienne du Tertre from the 16th-century Livres des danceries printed in Paris by pioneering early music publisher Pierre d’Attaignant. Hindemith himself had long been a devotee of what we now call ‘early music’, taking up the Baroque viola d’amore alongside his more modern viola in the 1920s, at

himself had long been a devotee of what we now call ‘early music’, taking up the Baroque viola d’amore alongside his more modern viola in the 1920s, at a time when few musicians bothered with old-fashioned instruments.Paul Hindemith

a time when few musicians bothered with old-fashioned instruments. And he’s unwaveringly faithful to Gervaise and du Tertre’s original melodies in his bracing new work, simply recasting them with affection and exquisite craftsmanship across a modern-day ensemble.

A lively, bouncing Galliarde follows a more stately Pavane in the opening movement, leading into a gentle, oboe-led Tourdion. The bransle was a versatile French dance, sometimes danced in either lines or circles, which spread to Italy, Spain and (as we’ll see) Scotland, and often heard in a short sequence. Accordingly, Hindemith follows his parping Bransle simple with a similarly lively Bransle de Bourgogne and a second Bransle simple, this time characterised by chattering woodwind, before a lilting Bransle d’Escosse – with perhaps a distant memory of Scottish folk music behind its rather melancholy melody. The elegant opening Pavane, now shorn of its livelier Galliarde, brings the Suite to a dignified conclusion.

We return to Antonio Vivaldi for tonight’s closing piece. It was Vivaldi himself who came up with the description ‘concerto con molti strumenti’ (literally ‘concerto with several instruments’) for about 30 of his 500 or so total concertos. And those works are among his most lavish and elaborate, combining winds, strings and other instruments in often large groups of soloists against his string ensemble accompaniment. He usually created them for special events: RV 558, for example, was probably written to celebrate the visit of Prince Frederick Christian of Poland to the Ospedale della Pietà in 1740. And its elaborate instrumentation needs some explaining. It’s written for two recorders, two mandolins, two chalumeaux (a forerunner of the clarinet), two theorbos

(or bass lutes), a solo cello, and two violins ‘in tromba marina’. These last instruments, and in particular their nautical-sounding qualifier, remain something of a mystery even today. It may be that Vivaldi was suggesting his violinists should emulate an archaic tromba marina, a single-stringed instrument whose distinctive buzz gave it a horn-like sound. But there’s no consensus as to how that should actually be achieved.

Vivaldi showcases his soloists in pairs in a bustling, stomping, richly scored opening movement, before a more yearning slow movement with a poignant melody in triplets for violin and mandolin soloists. Its closing movement returns to episodes for pairs of soloists, though Vivaldi mixes things up quite a bit more here, before a decisive unison ending.

© David KettleIt may be that Vivaldi was suggesting his violinists should emulate an archaic tromba marina, a single-stringed instrument whose distinctive buzz gave it a horn-like sound. But there’s no consensus as to how that should actually be achieved.

MAXIM’S BAROQUE INSPIRATIONS

Kindly supported by Donald and Louise MacDonald 24-26 Nov, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow | Aberdeen

ISRAEL IN EGYPT

1-2 Dec, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

FELIX YANIEWICZ AND THE SCOTTISH ENLIGHTENMENT

Co-financed by the Minister of Culture and National Heritage of the Republic of Poland 7-9 Dec, 7.30pm Dumfries | Edinburgh | Glasgow YEOL EUM SON PLAYS MOZART 15-16 Dec, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow SCO CHORUS CHRISTMAS CONCERT: THE HEART OF NIGHT 20-21 Dec, 7.30pm Edinburgh VIENNESE NEW YEAR 1,3,4 Jan, Various times Edinburgh | St Andrews | Ayr

MUSIQUE AMÉRIQUE

Kindly supported by SCO American Development Fund 12-13 Jan, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

AN EVENING WITH FRANÇOIS LELEUX

Our Edinburgh concert is sponsored by Institut Français Écosse 19-21 Jan, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow | Aberdeen

MÖDER DY / MOTHER WAVE

Part of Celtic Connections 2023 26-27 Jan, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

MOZART’S FLUTE CONCERTO 15-17 Feb, 7.30pm St Andrews | Edinburgh | Glasgow

MAXIM CONDUCTS BRAHMS

23-24 Feb, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

THE DREAM

Sponsored by Pulsant 2-4 Mar, 7.30pm Perth | Edinburgh | Glasgow

FOLK INSPIRATIONS WITH PEKKA 9-10 Mar, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

LES ILLUMINATIONS 15-17 Mar, 7.30pm St Andrews | Edinburgh | Glasgow

HANDEL: MUSIC FOR THE ROYALS

Our Edinburgh concert is kindly supported by The Usher Family 23-24 Mar, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

SCHUBERT’S

UNFINISHED SYMPHONY

Kindly supported by Claire and Mark Urquhart 30 Mar-1 Apr, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow | Aberdeen

SUMMER NIGHTS

WITH KAREN CARGILL 19-21 Apr, 7.30pm St Andrews | Edinburgh | Glasgow

BEETHOVEN’S FIFTH 27-29 Apr, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow | Aberdeen TCHAIKOVSKY’S FIFTH 4-5 May, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow BRAHMS REQUIEM 11-12 May, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

4 Royal Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 5AB +44 (0)131 557 6800 sco.org.uk

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra is a charity registered in Scotland No. SC015039. Company registration No. SC075079.

At the Scottish Chamber Orchestra Maxim Emelyanychev follows in the footsteps of just five previous Principal Conductors in the Orchestra’s 48-year history; Roderick Brydon (1974-1983), Jukka-Pekka Saraste (1987-1991), Ivor Bolton (1994-1996), Joseph Swensen (1996-2005) and Robin Ticciati (2009-2018).

Highlights of his 2021/22 season included debuts with some of the most prestigious international orchestras: Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Rotterdam Philharmonic, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester, Toronto Symphony and Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, and returns to the Antwerp Symphony, the Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse, the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic and a European tour with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, followed by appearances to the Radio-France Montpellier Festival and the Edinburgh International Festival.

In October 2022, Maxim toured the USA with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra and made his debut with the Berlin Philharmonic. Other touring in 2022/23 includes the New Japan Philharmonic, the Osaka Kansai Philharmonic, the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, the Helsinki Radio Symphony Orchestra, the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra. He will also return to the Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse and to the Royal Opera House in Mozart's Die Zauberflöte.

He regularly collaborates with renowned artists such as Max Emanuel Cenčić, Patrizia Ciofi, Joyce DiDonato, Franco Fagioli, Richard Goode, Sophie Karthäuser, Stephen Hough, Katia and Marielle Labèque, Marie-Nicole Lemieux, Julia Lezhneva, Alexei Lubimov, Riccardo Minasi, Xavier Sabata and Dmitry Sinkovsky.

Maxim is also a highly respected chamber musician. His most recent recording, of Brahms Violin Sonatas with long-time collaborator and friend Aylen Pritchin, was released on Aparté in December 2021 and has attracted outstanding reviews internationally. With the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Maxim has recorded the Schubert Symphony No 9 – the symphony with which he made his debut with the orchestra – which was released on Linn Records in November 2019.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

The internationally celebrated Scottish Chamber Orchestra is one of Scotland’s National Performing Companies.

Formed in 1974 and core funded by the Scottish Government, the SCO aims to provide as many opportunities as possible for people to hear great music by touring the length and breadth of Scotland, appearing regularly at major national and international festivals and by touring internationally as proud ambassadors for Scottish cultural excellence.

Making a significant contribution to Scottish life beyond the concert platform, the Orchestra works in schools, universities, colleges, hospitals, care homes, places of work and community centres through its extensive Creative Learning programme. The SCO is also proud to engage with online audiences across the globe via its innovative Digital Season.

An exciting new chapter for the SCO began in September 2019 with the arrival of dynamic young conductor Maxim Emelyanychev as the Orchestra’s Principal Conductor.

The SCO and Emelyanychev released their first album together (Linn Records) in November 2019 to widespread critical acclaim. The repertoire - Schubert’s Symphony No. 9 in C major ‘The Great’ –is the first symphony Emelyanychev performed with the Orchestra in March 2018.

The SCO also has long-standing associations with many eminent guest conductors including Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen, François Leleux, Pekka Kuusisto, Richard Egarr, Andrew Manze and John Storgårds.

The Orchestra enjoys close relationships with many leading composers and has commissioned almost 200 new works, including pieces by the late Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, Sir James MacMillan, Sally Beamish, Martin Suckling, Einojuhani Rautavaara, Karin Rehnqvist, Mark-Anthony Turnage, Nico Muhly, Anna Clyne and Associate Composer Jay Capperauld.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

Generations of our clients have trusted us to help build and preserve their wealth.

For over 250 years, they have relied on our expert experience to help make sense of a changing world. During that time we’ve earned an enviable reputation for a truly personal approach to managing wealth.

For those with over £250,000 to invest we o er a dedicated investment manager, with a cost structure and level of service, that generates exceptional client loyalty.

Find out more about investing with us today: Murray Clark at our Edinburgh o ce on 0131 221 8500, Gordon Ferguson at our Glasgow o ce on 0141 222 4000 or visit www.quiltercheviot.com

Investors should remember that the value of investments, and the income from them, can go down as well as up and that past performance is no guarantee of future returns. You may not recover what you invest. Quilter Cheviot and Quilter Cheviot Investment Management are trading names of Quilter Cheviot Limited. Quilter Cheviot Limited is registered in England with number 01923571, registered o ce at Senator House, 85 Queen Victoria Street, London, EC4V 4AB. Quilter Cheviot Limited is a member of the London Stock Exchange and authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority.