SCO.ORG.UK PROGRAMME MOZART’S FLUTE CONCERTO 15-17 Feb 2023

Season 2022/23

MOZART’S FLUTE CONCERTO

Wednesday 15 February, 7.30pm Younger Hall, St Andrews

Thursday 16 February, 7.30pm The Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh

Friday 17 February, 7.30pm City Halls, Glasgow

Debussy (arr. Caplet) Children’s Corner

Mozart Flute Concerto No 2 in D Major, K 314

Interval of 20 minutes

Stravinsky Danses concertantes

Mozart Idomeneo, Overture and Ballet Music Nos 1 & 2, K 366, 367

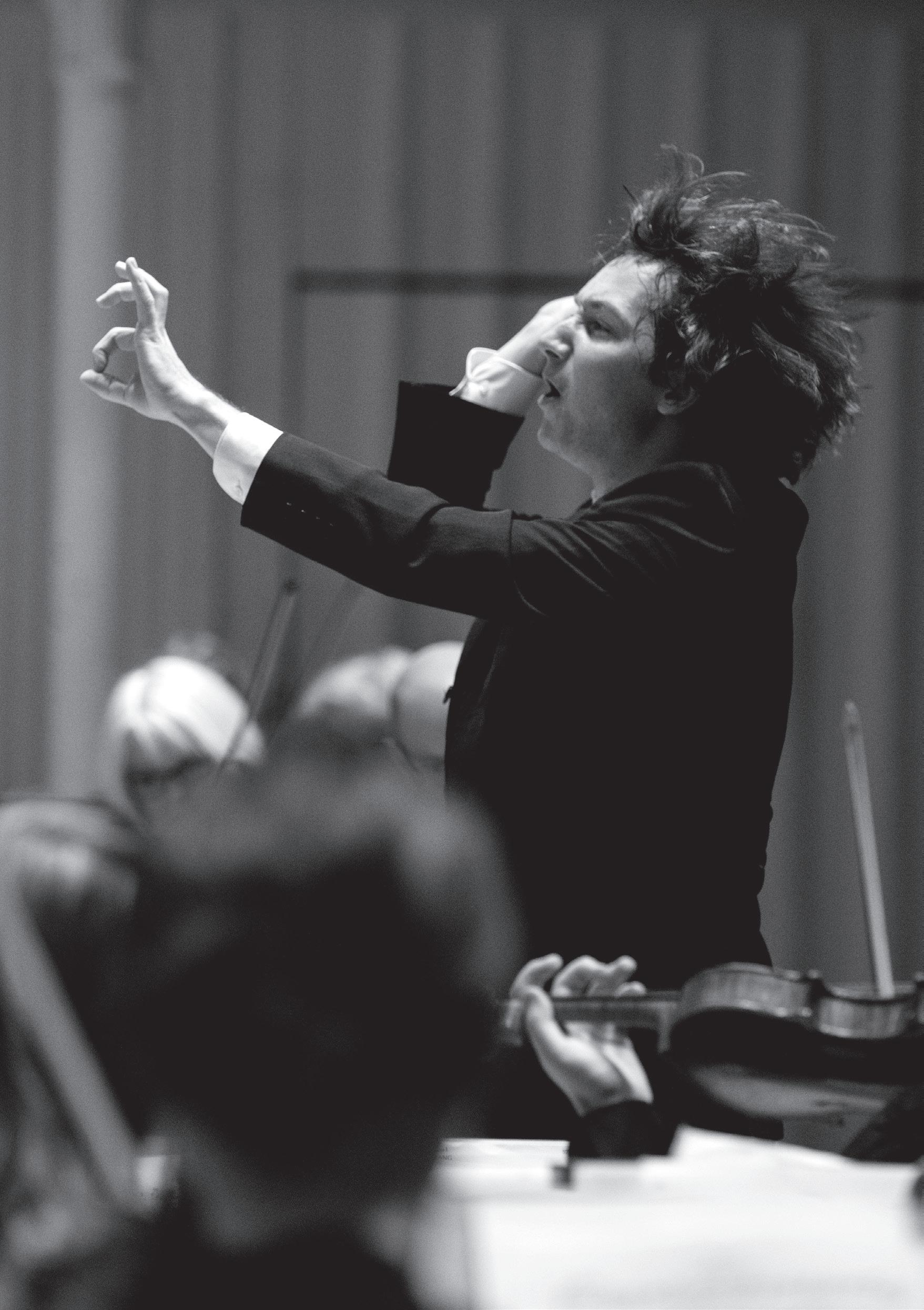

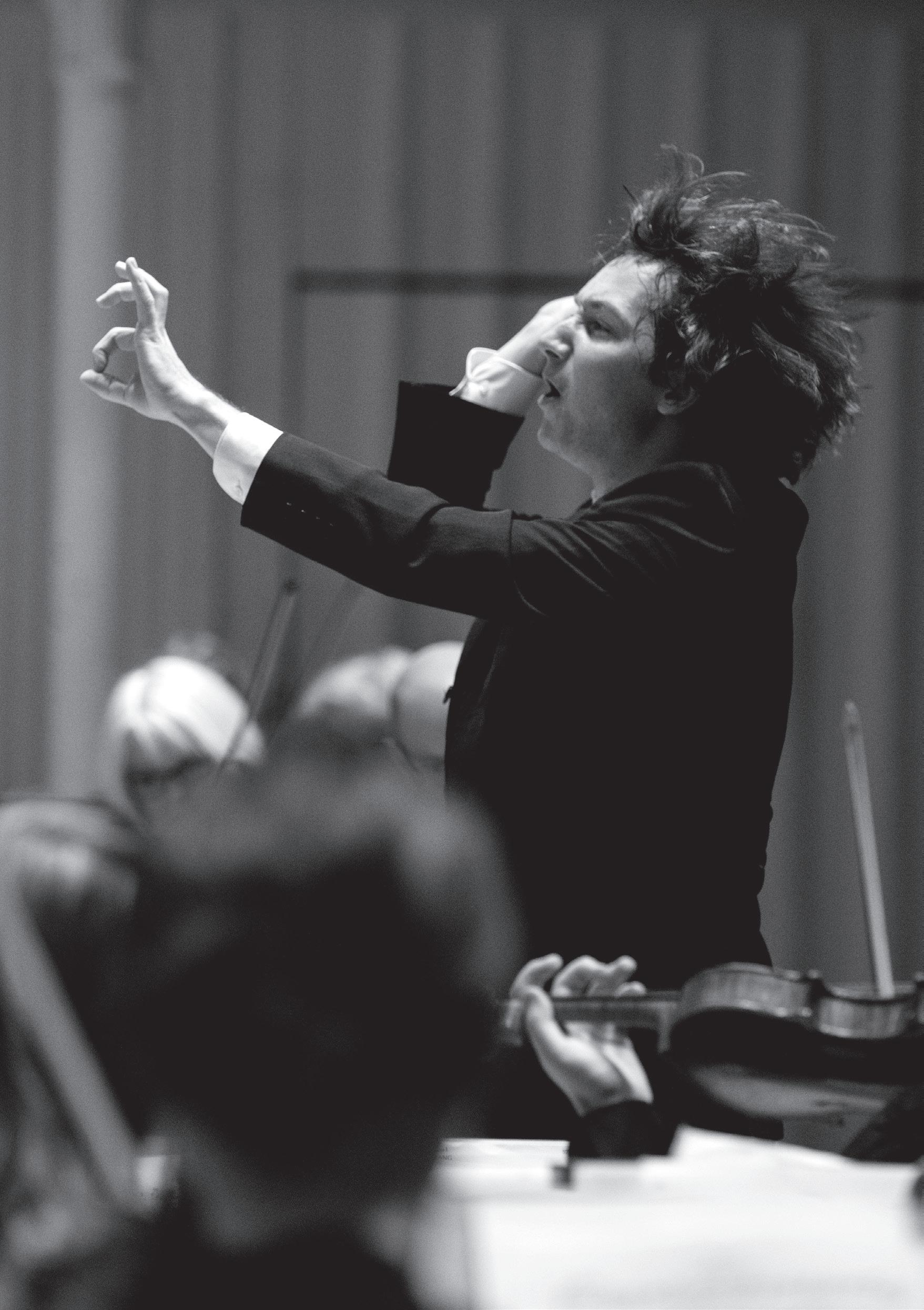

Joana Carneiro Conductor

André Cebrián Flute

Joana Carneiro

4

Royal Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 5AB +44 (0)131 557 6800 | info@sco.org.uk | sco.org.uk

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra is a charity registered in Scotland No. SC015039. Company registration No. SC075079.

Thank You FUNDING PARTNERS

The SCO is extremely grateful to the Scottish Government and to the City of Edinburgh Council for their continued support. We are also indebted to our Business Partners, all of the charitable trusts, foundations and lottery funders who support our projects, and to the very many individuals who are kind enough to give us financial support and who enable us to do so much. Each and every donation makes a difference and we truly appreciate it.

Core Funder

Authority

Learning Partner

Benefactor

Local

Creative

Business Partners

Key Funders

Delivered by

Su-a Lee

Sub-Principal Cello

Su-a Lee

Sub-Principal Cello

Thank You SCO DONORS

Diamond

Lucinda and Hew Bruce-Gardyne

Malcolm and Avril Gourlay

James and Felicity Ivory

Christine Lessels

Clair and Vincent Ryan

Alan and Sue Warner

Platinum

David Caldwell in memory of Ann

Tom and Alison Cunningham

John and Jane Griffiths

Judith and David Halkerston

J Douglas Home

Audrey Hopkins

David and Elizabeth Hudson

Dr and Mrs Peter Jackson

Dr Daniel Lamont

Chris and Gill Masters

Duncan and Una McGhie

Anne-Marie McQueen

James F Muirhead

Patrick and Susan Prenter

Mr and Mrs J Reid

Martin and Mairi Ritchie

Elaine Ross

Hilary E Ross

George Rubienski

Jill and Brian Sandford

Michael and Elizabeth Sudlow

Robert and Elizabeth Turcan

Tom and Natalie Usher

Anny and Bobby White

Finlay and Lynn Williamson

Ruth Woodburn

Gold

Lord Matthew Clarke

James and Caroline Denison-Pender

Andrew and Kirsty Desson

David and Sheila Ferrier

Chris and Claire Fletcher

James Friend

Iain Gow

Ian Hutton

Gordon Kirk

Robert Mackay and Philip Whitley

Mike and Karen Mair

Anne McAlister and Philip Sawyer

Gavin McEwan

Roy and Svend McEwan-Brown

John and Liz Murphy

Alison and Stephen Rawles

Andrew Robinson

Ian S Swanson

John-Paul and Joanna Temperley

Anne Usher

Catherine Wilson

Neil and Philippa Woodcock

G M Wright

Bruce and Lynda Wyer

Silver

Roy Alexander

Joseph I Anderson

Pamela Andrews and Alan Norton

Dr Peter Armit

William Armstrong

Fiona and Neil Ballantyne

Timothy Barnes and Janet Sidaway

The Batsleer Family

Jack Bogle

Jane Borland

Michael and Jane Boyle

Mary Brady

Elizabeth Brittin

John Brownlie

Laura Buist

Robert Burns

Sheila Colvin

Lorn and Camilla Cowie

Lord and Lady Cullen of Whitekirk

Adam and Lesley Cumming

Jo and Christine Danbolt

Dr Wilma Dickson

James Dunbar-Nasmith

Dr and Mrs Alan Falconer

Sheila Ferguson

Dr James W E Forrester

Dr William Fortescue

Jeanette Gilchrist

David Gilmour

Dr David Grant

Margaret Green

Andrew Hadden

J Martin Haldane

Ronnie and Ann Hanna

Ruth Hannah

Robin Harding

Roderick Hart

Norman Hazelton

Ron and Evelynne Hill

Clephane Hume

Tim and Anna Ingold

David and Pamela Jenkins

Catherine Johnstone

Julie and Julian Keanie

Marty Kehoe

Professor Christopher and Mrs Alison Kelnar

Dr and Mrs Ian Laing

Janey and Barrie Lambie

Graham and Elma Leisk

Geoff Lewis

Dorothy A Lunt

Vincent Macaulay

Joan MacDonald

Isobel and Alan MacGillivary

Jo-Anna Marshall

James McClure in memory of Robert Duncan

Gavin McCrone

Michael McGarvie

Brian Miller

James and Helen Moir

Alistair Montgomerie

Margaret Mortimer and Ken Jobling

Andrew Murchison

Hugh and Gillian Nimmo

David and Tanya Parker

Hilary and Bruce Patrick

Maggie Peatfield

John Peutherer in memory of Audrey

Peutherer

James S Potter

Alastair Reid

Fiona Reith

Olivia Robinson

Catherine Steel

Ian Szymanski

Michael and Jane Boyle

Douglas and Sandra Tweddle

Margaretha Walker

James Wastle

C S Weir

Bill Welsh

Roderick Wylie

We believe the thrill of live orchestral music should be accessible to everyone, so we aim to keep the price of concert tickets as fair as possible. However, even if a performance were completely sold out, we would not cover the presentation costs.

We are indebted to everyone acknowledged here who gives philanthropic gifts to the SCO of £300 or greater each year, as well as those who prefer to remain anonymous. We are also incredibly thankful to the many individuals not listed who are kind enough to support the Orchestra financially, whether that is regularly or on an ad hoc basis. Every single donation makes a difference and we are truly grateful.

Become a regular donor, from as little as £5 a month, by contacting Mary Clayton on 0131 478 8369 or mary.clayton@sco.org.uk

Thank You PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR'S CIRCLE

Our Principal Conductor’s Circle is made up of individuals who share the SCO’s vision to bring the joy of music to as many people as possible. These individuals are a special part of our musical family, and their commitment and generosity benefit us all – musicians, audiences and creative learning participants alike. We would like to extend our grateful thanks to them for playing such a key part in the future of the SCO.

American Development Fund

Erik Lars Hansen and Vanessa C L Chang

Creative Learning Fund

David and Maria Cumming

Annual Fund

James and Patricia Cook

Hedley G Wright

CHAIR SPONSORS

Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen

Donald and Louise MacDonald

Chorus Director Gregory Batsleer

Anne McFarlane

Principal Second Violin

Marcus Barcham Stevens

Jo and Alison Elliot

Principal Viola Max Mandel

Kenneth and Martha Barker

Viola Steve King

Sir Ewan and Lady Brown

Principal Cello Philip Higham

The Thomas Family

Cello Donald Gillan

Professor Sue Lightman

Visiting Artists Fund

Colin and Sue Buchan

Anne and Matthew Richards

Productions Fund

The Usher Family

International Touring Fund

Gavin and Kate Gemmell

Cello Eric de Wit

Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund

Principal Double Bass Nikita Naumov

Dr Caroline N Hahn

Principal Flute André Cebrián

Claire and Mark Urquhart

Principal Oboe Robin Williams

Hedley G Wright

Principal Clarinet Maximiliano Martín

Stuart and Alison Paul

Principal Bassoon Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Claire and Anthony Tait

Principal Timpani Louise Lewis Goodwin

Geoff and Mary Ball

–––––

Our Musicians YOUR ORCHESTRA

First Violin

Joel Bardolet

Mary Ellen Woodside

Kana Kawashima

Siún Milne

Fiona Alexander

Amira Bedrush-McDonald

Sarah Bevan-Baker

Andrew Roberts

Second Violin

Marcus Barcham Stevens

Gordon Bragg

Rachel Spencer

Michelle Dierx

Niamh Lyons

Rachel Smith

Viola

Oscar Holch

Zoë Matthews

Steve King

Liam Brolly

Cello

Su-a Lee

Donald Gillan

Kim Vaughan

Christoff Fourie

Bass

Nikita Naumov

Louis van Der Mespel

Flute

André Cebrián

Marta Gómez

Alba Vinti

Piccolo

Alba Vinti

Oboe

Robin Williams

Katherine Bryer

Clarinet

Cristina Mateo Saez

William Stafford

Bassoon

Information correct at the time of going to print

Horn

Steve Stirling

Jamie Shield

Helena Jacklin

Harry Johnstone

Trumpet

Peter Franks

Shaun Harrold

Trombone

Cillian Ó’Ceallacháin

Timpani

Louise Lewis Goodwin

Percussion

Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Alison Green

Louise Lewis Goodwin

Kate Openshaw

Harp

Eleanor Hudson

Kana Kawashima

First Violin

WHAT YOU ARE ABOUT TO HEAR

Debussy (1862–1918)

Children’s Corner (1908)

Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum

Jimbo's Lullaby

Serenade for the Doll

The Snow Is Dancing

The Little Shepherd

Cake-walk

Mozart (1756-1791)

Flute Concerto No 2 in D Major, K 314 (1778)

Allegro aperto

Adagio ma non troppo

Rondeau: Allegro

Stravinsky (1882-1971)

Danses concertantes (1942)

Marche-introduction

Pas d'action. Con moto

Thème varié. Lento

Pas de deux. Risoluto - Andante sostenuto

Marche-conclusion

Mozart (1756-1791)

Idomeneo, Overture and Ballet Music

Nos 1 & 2, K 366, 367 (1780–81)

Overture

No 1: Chaconne

No 2: Pas seul

From an anglophile Parisian to an Austrian job-hunting in (what’s now) Germany, and even a Russian expat living it large in LA, there’s nothing if not variety in tonight’s century-leaping, country-hopping concert. What brings all of today’s music together, however, is a sense of conciseness, focus and vivid picture painting – as well as, after the interval at least, a passion for dance.

Musical picture painting is precisely what Claude Debussy had in mind in his Children’s Corner, a set of six pieces originally for solo piano that he wrote between 1906 and 1908. Despite what his voluptuous, sensual music might suggest, Debussy was notorious for being bad-tempered and irascible in personal encounters. But for his daughter ClaudeEmma – affectionately nicknamed Chouchou – he expressed nothing but tenderness and affection. So much so, in fact, that when she was barely three years old, he embarked on a collection of pieces portraying her favourite toys and activities.

Unlike, for example, Ravel’s equally childfocused Ma mère l’oye (Mother Goose), Debussy wasn’t out to create music for Chouchou or other children to play themselves (though he toned down some of his more extravagant pianistic demands in what became Children’s Corner, making it suitable for fairly experienced younger fingers). Instead, he imagined a world seen through the eyes of a child, painting musical pictures of a certain naive innocence, though the pieces undeniably suggest a wistful nostalgia for the simplicity and wonder of childhood that could only an adult could experience.

Children’s Corner, by the way, is the work’s correct original title, though Debussy’s publisher Durand helpfully added its French translation Coin des enfants in brackets on the score’s contents page. Debussy was an ardent admirer of all things English, and he and his wife Emma Bardac had engaged an English nanny to help with looking after Chouchou. As a result, all of the little girl’s toys (and therefore also the titles of Debussy’s individual movements) had English names. English-born pianist Harold Bauer gave Children’s Corner its first performance, in Paris on 18 December 1908. It was just three years later that the orchestral version you hear tonight – whose orchestration Debussy had entrusted to his close friend and fellow composer André Caplet – received its first performance.

Debussy begins with one of the grandest, most mysterious and most entrancing

toys a young child can encounter: a piano. In the opening ‘Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum’, he imagines a youngster running through finger-strengthening exercises (the piece’s title is a sly nod to classic volumes of piano pedagogy called Gradus ad Parnassum, or ‘Steps to Parnassus’, home to the Muses of Greek mythology), whose ceaseless patterning Caplet entrusts to bubbling woodwind. The infant’s mind wanders to increasingly expressive, fantastical improvisations, only to be brought back, perhaps by a passing parent, to what they were supposed to be practising.

‘Jimbo’s Lullaby’ is a portrait of Chouchou’s cuddly elephant, named after the illustrious pachyderm Jumbo who spent a brief time housed in Paris’s Jardin des Plantes before ending up in PT Barnum’s travelling circus. The piece

Instead,heimagineda worldseenthroughthe eyesofachild,painting musicalpicturesofa certainnaiveinnocence, thoughthepieces undeniablysuggesta wistfulnostalgiaforthe simplicityandwonderof childhoodthatcouldonly anadultcouldexperience.

Claude Debussy

begins, appropriately enough, with a low-pitched, plodding melody in the double basses, and there’s surely a sense of gentle sadness in the music at the magnificent beast’s captivity. Debussy’s mis-spelling of his subject, it’s been suggested, had less to do with ignorance and more to do with poking fun at the nasal Parisian accent that might make ‘Jumbo’ sound more like ‘Jimbo’.

‘Serenade for the Doll’ is an elegant, refined evocation of Chouchou’s porcelain doll, in music whose spinning figurations make great use of oriental-sounding modes. The young girl gazes from the warmth of her room at wintry precipitation in ‘The Snow is Dancing’, which mixes magic and a certain chilly menace in its icy repetitions on strings and oboe. The dream-like ‘The Little Shepherd’ begins with unaccompanied piping from the solitary boy, lost in the landscape, and unfolds across three carefree, al fresco episodes.

More than a century after Children’s Corner’s composition, we might find the original title of the suite’s closing movement, ‘Cake-walk’, somewhat problematic, as we also might its depiction of a blackface doll doing a strutting, music hall-style dance all the rage in Paris in the first years of the 20th century. More interesting, however, is Debussy’s appropriation of dance-hall ragtime rhythms – especially when butted up against the luscious quotations from Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde that he sarcastically inserts about halfway through. At the piece’s 1908 premiere, Debussy reportedly paced the corridors, frightened that Wagner lovers might be up in arms at his cheek. Thankfully, they saw the funny side.

From Paris just before the Great War, we jump to Mannheim in what’s now southern Germany in 1777 for tonight’s next piece. The 21-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart had quit his job in his birth city of Salzburg with its over-demanding, underappreciative ruler, Prince-Archbishop Hieronymus Colloredo, and had set off to tour the musical centres of Europe with his mother in search of work. Mannheim was the Mozarts’ second stop (after Augsburg), and it was home at the time to one of Europe’s most accomplished, most professional and most pioneering court orchestras. Under the guidance of music director Johann Stamitz, the Mannheim musicians were out to wring musical performance for every last drop of intense expression they could manage, with surging crescendos, dramatic pauses, even stormy basslines and chirruping birdsong to thrill and delight their listeners.

No wonder, then, that Mozart spent a joyful and fulfilling five months in the city (even if he was unsuccessful in his search for a permanent job). His happiness was helped, no doubt, by a lengthy flirtation with young Aloysia Weber, who he’d met there (she later spurned his affections, and he ended up marrying her younger sister, Constanze). Mozart also got to know the Mannheim musicians well, and struck up a particularly close friendship with the court orchestra’s flautist, Johann Baptist Wendling, who was determined to get a flute concerto out of the young composer. Wendling enlisted the help of wealthy amateur flautist Ferdinand de Jean, who commissioned no fewer than three flute concertos and three flute quartets from Mozart.

In the end, however, the composer only managed two of each, and only received a

portion of the commissioning fee as a result. For many years, only one of those two flute concertos was thought to have survived, until a set of parts turned up in Salzburg in 1920 that proved to be the ‘missing’ piece, tonight’s Concerto in D major, K 314. Those parts bore an uncanny resemblance, too, to an earlier Oboe Concerto that Mozart had written for Salzburg player Giuseppe Ferlendis, and which Mannheim oboist Friedrich Ramm loved so much that he played it no fewer than five times during Mozart’s stay. How the concertos’ commissioner, Ferdinand de Jean, remained unaware that one of the pieces written for him wasn’t even original is a mystery – though Mozart ensured sufficient changes to the music for it to feel and sound idiomatic on the new instrument.

It was in justifying his inability to complete de Jean’s commission that Mozart made a

puzzling reference in a letter home to his father Leopold, writing: ‘You know that I become quite powerless whenever I am obliged to write for an instrument which I cannot bear.’ It’s left flautists and Mozart scholars scratching their heads ever since. Did he really mean he hated the flute? It seems unlikely, given the elaborate, eloquent flute writing across his music, and the efforts he made to showcase the instrument in this buoyant, sensitively crafted Concerto. More probable was that Mozart’s apparent hostility was simply an excuse for not doing the work he’d promised.

Indeed, the flute makes quite a flourish at its first entry in the Concerto’s light and airy opening movement, and there’s no lack of athletic virtuosity in its opening theme. Mozart cunningly contrasts the instrument’s brilliant higher register

‘You know that I become quitepowerlesswhenever Iamobligedtowriteforan instrument which I cannot bear.’ It’s left flautists and Mozart scholars scratchingtheirheadsever since.Didhereallymean he hated the flute?

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

with more plangent, richer passages lower in its range in his elegant, gently flowing slow movement. His finale is quick and bouncy, with a playful, somewhat mischievous theme that returns several times across the movement, rather furtively on the solo flute, then far more confidently from the full orchestra.

It was dance that secured the worldwide reputation of Russian-born Igor Stravinsky, specifically the trio of succulent scores he produced for Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in Paris – The Firebird , Petrushka and The Rite of Spring – around the same time that Debussy was writing his Children’s Corner . Around three decades later, Danses concertantes was the first major work that Stravinsky composed in his new home of West Hollywood, where he settled in 1941 after fleeing war-ravaged

Europe. The official commission came from Los Angeles movie composer and conductor Werner Janssen, for his own Symphony Orchestra. But legendary choreographer George Balanchine –who unveiled a dance interpretation in New York in 1944 – later claimed that Stravinsky had actually written the piece for him, and that he’d visited the composer on the West Coast several times to discuss the project.

Stravinsky himself always maintained that he’d written it as a concert work, not specifically for the stage. And, perhaps unconcerned about biting the hand the fed him, the composer also confided to a San Francisco Chronicle critic that he’d kept Danses concertantes brief because ‘the attention span of today’s audience is limited, and the problem of the presentday composer is one of condensation’.

Aroundthreedecades later,Dansesconcertantes wasthefirstmajorwork thatStravinskycomposed inhisnewhomeofWest Hollywood,wherehe settledin1941after fleeingwar-ravaged Europe.

Igor Stravinsky

Judge for yourself whether he was successful with that.

With its crisp rhythms, acerbic harmonies and switchback mood shifts, Danses concertantes is indeed a brisk and brusque creation, and it and his 'Dumbarton Oaks' Concerto of 1938 have even been termed ‘Stravinsky’s Brandenburgs’ in reference to JS Bach’s iconic concertos from two centuries earlier. Following a bracing opening march, the suite of five pieces moves from a gentle ‘Pas d’action’ to an elegant theme and variations (listen out for a swaggering, cowboy-style dance), then a tender ‘Pas de deux’, before the march returns to bring things to a rousing conclusion.

We stay with dance in tonight’s closing piece, the Overture and ballet music that Mozart wrote for his opera Idomeneo. But hang on: aren’t ballet and opera meant to be two entirely separate things? Not for French audiences, who loved a ballet segment as part of an opera to offer a bit of light relief from following convoluted plots. And they’d be furious if they didn’t get it. Richard Wagner specifically wrote a ballet section for the Parisian premiere of his opera Tannhäuser in 1861, but he inserted it far too early in the opera’s storyline. As a result, latecomers missed the very bit of the evening they’d come to see. Tannhäuser in Paris survived just three performances.

Idomeneo was commissioned from Mozart by Karl Theodor, Elector of Bavaria, who nonetheless hoped to emulate the spectacle and variety of French opera in the work, which was first performed at his Residenz in Munich on 29 January 1781. By that time, Mozart

had returned, unsuccessful in his jobhunting, from his Europe-hopping trip, during which he’d lost his mother to an unknown illness in Paris. Back in Salzburg, he’d reluctantly returned to work for Prince-Archbishop Hieronymus Colloredo. One get-out clause in his new contract, however, allowed Mozart a leave of absence if he was composing an opera elsewhere – which was precisely the case with his Idomeneo commission in Munich.

Set on the island of Crete immediately after the Trojan War, Idomeneo tells a Romeo and Juliet-like story of Ilia, daugher of King Priam of Troy, and her love for Idamante, son of the Cretan King Idomeneo. When Idomeneo is rescued from drowning by the sea god Neptune, the King promises to make a sacrifice of the first living thing he sees – which happens, tragically, to be his own son, Idamante.

Mozart establishes the opera’s grand, classical tone right from the majestic opening of his Overture, which soon breaks into music that’s far more overtly festive. The threat of tragedy is never far away, however, as the sadder melody of the Overture’s second main theme suggests. The piece ends in an unusually quiet, tentative manner: on the stage, it would lead directly into the first scene, but tonight, its hushed ending provides a transition into the opera’s ballet music. A strutting, confident ‘Chaconne’, full of pomp and ceremony, leads straight into a quieter ‘Annonce’, a contrasting, far stormier ‘Chaconne’, and then a ‘Pas seul’ that has an almost Handelian grandeur to its slower opening section.

© David Kettle

Conductor JOANA CARNEIRO

Acclaimed Portuguese conductor Joana Carneiro is Principal Guest Conductor of the Real Filharmonia de Galicia. She is also Artistic Director of the Estágio Gulbenkian para Orquestra, a post she has held since 2013.

Joana Carneiro was Principal Conductor of the Orquestra Sinfonica Portuguesa at Teatro Sao Carlos in Lisbon from 2014 until January 2022. From 2009 to 2018 she was Music Director of Berkeley Symphony, succeeding Kent Nagano as only the third music director in the 40-year history of the orchestra. She was also official guest conductor of the Gulbenkian Orchestra from 2006 to 2018.

Recent and future guest conducting highlights include engagements with the BBC Symphony, Philharmonia Orchestra, Royal Northern Sinfonia, Orquesta Sinfónica de Castilla y León, Gothenburg Symphony, Norrkoping Symphony, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic (whom she conducted at the Nobel Prize Ceremony in December 2017), Swedish Radio Symphony, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, National Arts Centre Orchestra in Ottawa and the BBC Scottish Symphony.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

Flute ANDRÉ CEBRIÁN

Spanish Flautist André Cebrián studied in his home town Santiago de Compostela with Luis Soto, Laurent Blaiteau and Pablo Sagredo. He then went on to study with János Bálint in HfM Detmold (Germany) and with Jacques Zoon in HEM Gèneve (Switzerland).

André’s first orchestral experiences at the National Youth Orchestra of Spain, the Britten-Pears Orchestra and the Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester led him to perform with such orchestras as the Orquestra de Cadaqués, Staatkskapelle Dresden and Orchestra Mozart. He performs regularly as a Guest Principal Flute with the Sinfónica de Castilla-León, Filarmónica de Gran Canaria, Sinfónica de Barcelona, Gran Teatro del Liceu, Malaysian Philharmonic and Spira Mirabilis.

When he is not playing in the Orchestra you can find him performing with his wind quintets Azahar Ensemble and Natalia Ensemble - where he is also the artistic director and arranger - or in one of his duo projects with harpist Bleuenn Le Friec, or guitarist Pedro Mateo González. In 2019 he founded the Festival de Música de Cámara de Anguiano in La Rioja (Spain).

He loves sharing his passion for music with his students at the Conservatorio Superior de Aragón, Barenboim-Said Foundation and the youth orchestras he coaches each season. André joined the SCO as Principal Flute in early 2020.

André's Chair is kindly supported by Claire and Mark Urquhart

Biography

SCOTTISH CHAMBER ORCHESTRA

The internationally celebrated Scottish Chamber Orchestra is one of Scotland’s National Performing Companies.

Formed in 1974 and core funded by the Scottish Government, the SCO aims to provide as many opportunities as possible for people to hear great music by touring the length and breadth of Scotland, appearing regularly at major national and international festivals and by touring internationally as proud ambassadors for Scottish cultural excellence.

Making a significant contribution to Scottish life beyond the concert platform, the Orchestra works in schools, universities, colleges, hospitals, care homes, places of work and community centres through its extensive Creative Learning programme. The SCO is also proud to engage with online audiences across the globe via its innovative Digital Season.

An exciting new chapter for the SCO began in September 2019 with the arrival of dynamic young conductor Maxim Emelyanychev as the Orchestra’s Principal Conductor.

The SCO and Emelyanychev released their first album together (Linn Records) in November 2019 to widespread critical acclaim. The repertoire - Schubert’s Symphony No. 9 in C major ‘The Great’ –is the first symphony Emelyanychev performed with the Orchestra in March 2018.

The SCO also has long-standing associations with many eminent guest conductors including Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen, François Leleux, Pekka Kuusisto, Richard Egarr, Andrew Manze and John Storgårds.

The Orchestra enjoys close relationships with many leading composers and has commissioned almost 200 new works, including pieces by the late Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, Sir James MacMillan, Sally Beamish, Martin Suckling, Einojuhani Rautavaara, Karin Rehnqvist, Mark-Anthony Turnage, Nico Muhly, Anna Clyne and Associate Composer Jay Capperauld.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

22/23

MAXIM CONDUCTS BRAHMS

23-24 Feb, 7.30pm

Edinburgh | Glasgow

BRAHMS’S CHAMBER PASSIONS

26 Feb, 3pm Edinburgh

THE DREAM

Sponsored by Pulsant

2-4 Mar, 7.30pm

Perth | Edinburgh | Glasgow

FOLK INSPIRATIONS WITH PEKKA

9-10 Mar, 7.30pm

Edinburgh | Glasgow

TRANSCENDENTAL VISIONS WITH PEKKA AND SAM

12 Mar, 3pm Edinburgh

LES ILLUMINATIONS

15-17 Mar, 7.30pm

St Andrews | Edinburgh | Glasgow

4 Royal Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 5AB +44 (0)131 557 6800 sco.org.uk

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra is a charity registered in Scotland No. SC015039. Company registration No. SC075079.

HANDEL:

MUSIC FOR THE ROYALS

Our Edinburgh concert is kindly supported by The Usher Family

23-24 Mar, 7.30pm

Edinburgh | Glasgow

SCHUBERT’S UNFINISHED SYMPHONY

Kindly supported by Claire and Mark Urquhart

30 Mar-1 Apr, 7.30pm

Edinburgh | Glasgow | Aberdeen

SUMMER NIGHTS WITH KAREN CARGILL

19-21 Apr, 7.30pm

St Andrews | Edinburgh | Glasgow

BEETHOVEN’S FIFTH

27-29 Apr, 7.30pm

Edinburgh | Glasgow | Aberdeen

TCHAIKOVSKY’S FIFTH

4-5 May, 7.30pm

Edinburgh | Glasgow

BRAHMS REQUIEM

11-12 May, 7.30pm

Edinburgh | Glasgow

CONCERTS

us on

SEASON

SCO.ORG.UK Find

23-24 Feb, 7.30pm, Usher Hall, Edinburgh | City Halls, Glasgow MAXIM CONDUCTS BRAHMS Maxim Emelyanychev Conductor Aylen Pritchin Violin INCLUDING 18 and Under FREE BOOK NOW SCO.ORG.UK Company Registration Number: SC075079. A charity registered in Scotland No. SC015039.

WE BUILD RELATIONSHIPS THAT LAST GENERATIONS.

Generations of our clients have trusted us to help build and preserve their wealth.

For over 250 years, they have relied on our expert experience to help make sense of a changing world. During that time we’ve earned an enviable reputation for a truly personal approach to managing wealth.

For those with over £250,000 to invest we o er a dedicated investment manager, with a cost structure and level of service, that generates exceptional client loyalty.

Find out more about investing with us today: Murray Clark at our Edinburgh o ce on 0131 221 8500, Gordon Ferguson at our Glasgow o ce on 0141 222 4000 or visit www.quiltercheviot.com

Investors should remember that the value of investments, and the income from them, can go down as well as up and that past performance is no guarantee of future returns. You may not recover what you invest. Quilter Cheviot and Quilter Cheviot Investment Management are trading names of Quilter Cheviot Limited. Quilter Cheviot Limited is registered in England with number 01923571, registered o ce at Senator House, 85 Queen Victoria Street, London, EC4V 4AB. Quilter Cheviot Limited is a member of the London Stock Exchange and authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority. INVESTING FOR GENERATIONS

BE PART OF OUR FUTURE

times, your support is more valuable than

For more information on how you can become a regular donor, please get in touch with Mary Clayton on 0131 478 8369 or email mary.clayton@sco.org.uk.

SCO.ORG.UK/SUPPORT-US

The SCO is a charity registered in Scotland No SC015039. A warm welcome to everyone who has

our

of

and a big thank you to everyone who

to secure

future. Monthly or annual contributions from our

a real

to the SCO’s

to

these

recently joined

family

donors,

is helping

our

donors make

difference

ability

budget and plan ahead with more confidence. In

extraordinarily challenging

ever.

Su-a Lee

Sub-Principal Cello

Su-a Lee

Sub-Principal Cello