MUSIQUE AMÉRIQUE

SCO.ORG.UK PROGRAMME

12-13 Jan 2023

4 Royal Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 5AB +44 (0)131 557 6800 | info@sco.org.uk | sco.org.uk

Chamber

is a charity registered in Scotland No.

Company registration

Kindly supported by SCO American Development Fund Season 2022/23 MUSIQUE AMÉRIQUE Joseph Swensen Maximiliano Martín Thursday 12 January, 7.30pm The Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh Friday 13 January, 7.30pm City Halls, Glasgow Milhaud La création du monde Copland Clarinet Concerto Interval of 20 minutes Bernstein (orch. Ramin) Sonata for Clarinet and Orchestra Poulenc Sinfonietta Joseph Swensen Conductor Maximiliano Martín Clarinet

The Scottish

Orchestra

SC015039.

No. SC075079.

The SCO is extremely grateful to the Scottish Government and to the City of Edinburgh Council for their continued support. We are also indebted to our Business Partners, all of the charitable trusts, foundations and lottery funders who support our projects, and to the very many individuals who are kind enough to give us financial support and who enable us to do so much. Each and every donation makes a difference and we truly appreciate it.

Core Funder

Benefactor Local Authority Creative Learning Partner

You FUNDING PARTNERS

Thank

Su-a Lee

Sub-Principal Cello

Business Partners

Key Funders

Delivered by

Delivered by

Thank You

SCO DONORS

Diamond

Lucinda and Hew Bruce-Gardyne Malcolm and Avril Gourlay

James and Felicity Ivory

Christine Lessels

Clair and Vincent Ryan Alan and Sue Warner

Platinum

Eric G Anderson

David Caldwell in memory of Ann Tom and Alison Cunningham

John and Jane Griffiths

Judith and David Halkerston

J Douglas Home Audrey Hopkins

David and Elizabeth Hudson Dr and Mrs Peter Jackson

Dr Daniel Lamont Chris and Gill Masters Duncan and Una McGhie Anne-Marie McQueen James F Muirhead

Patrick and Susan Prenter

Mr and Mrs J Reid

Martin and Mairi Ritchie

Elaine Ross

Hilary E Ross

George Rubienski

Jill and Brian Sandford

Michael and Elizabeth Sudlow

Robert and Elizabeth Turcan

Tom and Natalie Usher

Anny and Bobby White Finlay and Lynn Williamson Ruth Woodburn

Gold

Lord Matthew Clarke James and Caroline Denison-Pender Andrew and Kirsty Desson David and Sheila Ferrier Chris and Claire Fletcher James Friend

Iain Gow

Ian Hutton

Gordon Kirk

Robert Mackay and Philip Whitley Mike and Karen Mair Anne McAlister and Philip Sawyer Gavin McEwan Roy and Svend McEwan-Brown Alan Moat

John and Liz Murphy Alison and Stephen Rawles Andrew Robinson

Ian S Swanson

John-Paul and Joanna Temperley Anne Usher

Catherine Wilson Neil and Philippa Woodcock G M Wright

Bruce and Lynda Wyer

Silver

Roy Alexander

Joseph I Anderson

Pamela Andrews and Alan Norton

Dr Peter Armit

William Armstrong Fiona and Neil Ballantyne

Timothy Barnes and Janet Sidaway

The Batsleer Family

Jack Bogle

Jane Borland

Michael and Jane Boyle Mary Brady

Elizabeth Brittin

John Brownlie

Laura Buist

Robert Burns

Sheila Colvin

Lorn and Camilla Cowie

Lord and Lady Cullen of Whitekirk Adam and Lesley Cumming Jo and Christine Danbolt

Dr Wilma Dickson

James Dunbar-Nasmith Dr and Mrs Alan Falconer Sheila Ferguson

Dr James W E Forrester Dr William Fortescue

Jeanette Gilchrist

David Gilmour

Dr David Grant Margaret Green Andrew Hadden

J Martin Haldane Ronnie and Ann Hanna Ruth Hannah Robin Harding Roderick Hart Norman Hazelton Ron and Evelynne Hill Clephane Hume Tim and Anna Ingold David and Pamela Jenkins Catherine Johnstone Julie and Julian Keanie Marty Kehoe Professor Christopher and Mrs Alison Kelnar Dr and Mrs Ian Laing Janey and Barrie Lambie Graham and Elma Leisk Geoff Lewis Dorothy A Lunt Vincent Macaulay Joan MacDonald Isobel and Alan MacGillivary Jo-Anna Marshall

James McClure in memory of Robert Duncan Gavin McCrone Michael McGarvie Brian Miller James and Helen Moir Alistair Montgomerie Margaret Mortimer and Ken Jobling Andrew Murchison Hugh and Gillian Nimmo David and Tanya Parker Hilary and Bruce Patrick Maggie Peatfield John Peutherer in memory of Audrey Peutherer

James S Potter Alastair Reid Fiona Reith Olivia Robinson Catherine Steel Ian Szymanski Michael and Jane Boyle Douglas and Sandra Tweddle Margaretha Walker James Wastle C S Weir Bill Welsh Roderick Wylie

We believe the thrill of live orchestral music should be accessible to everyone, so we aim to keep the price of concert tickets as fair as possible. However, even if a performance were completely sold out, we would not cover the presentation costs.

We are indebted to everyone acknowledged here who gives philanthropic gifts to the SCO of £300 or greater each year, as well as those who prefer to remain anonymous. We are also incredibly thankful to the many individuals not listed who are kind enough to support the Orchestra financially, whether that is regularly or on an ad hoc basis. Every single donation makes a difference and we are truly grateful.

Become a regular donor, from as little as £5 a month, by contacting Mary Clayton on 0131 478 8369 or mary.clayton@sco.org.uk

Thank You PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR'S CIRCLE

Our Principal Conductor’s Circle is made up of individuals who share the SCO’s vision to bring the joy of music to as many people as possible. These individuals are a special part of our musical family, and their commitment and generosity benefit us all – musicians, audiences and creative learning participants alike. We would like to extend our grateful thanks to them for playing such a key part in the future of the SCO.

American Development Fund

Erik Lars Hansen and Vanessa C L Chang Kenneth and Martha Barker

Creative Learning Fund David and Maria Cumming

Annual Fund James and Patricia Cook Dr Caroline N Hahn Hedley G Wright

CHAIR SPONSORS

Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen

Donald and Louise MacDonald

Chorus Director Gregory Batsleer Anne McFarlane

Viola Steve King Sir Ewan and Lady Brown

Principal Cello Philip Higham The Thomas Family

Cello Donald Gillan

Professor Sue Lightman Cello Eric de Wit Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund

Visiting Artists Fund

Colin and Sue Buchan Anne and Matthew Richards Productions Fund The Usher Family

International Touring Fund Gavin and Kate Gemmell

Principal Second Violin Marcus Barcham Stevens Jo and Alison Elliot

Principal Flute André Cebrián Claire and Mark Urquhart

Principal Oboe Robin Williams Hedley G Wright

Principal Clarinet Maximiliano Martín Stuart and Alison Paul

Principal Bassoon Cerys Ambrose-Evans Claire and Anthony Tait

Principal Timpani Louise Lewis Goodwin Geoff and Mary Ball

–––––

Our Musicians YOUR ORCHESTRA

First Violin

Joel Bardolet

Siún Milne Kana Kawashima Aisling O’Dea Amira Bedrush-McDonald Sian Holding Stewart Webster Emily Ward

Second Violin

Marcus Barcham Stevens Gordon Bragg Rachel Spencer Wen Wang Niamh Lyons Rachel Smith Viola Ásdís Valdimarsdóttir Jessica Beeston

Brian Schiele Liam Brolly Cello

Philip Higham Su-a Lee Donald Gillan Eric de Wit Bass

Nikita Naumov Ben Burnley

Flute

André Cebrián Carolina Patricio Piccolo André Cebrián

Oboe Robin Williams Katherine Bryer Clarinet Cristina Mateo Sáez William Stafford

Information correct at the time of going to print

Horn

Jože Rošer

Harry Johnstone Trumpet Peter Franks Brian McGinley Trombone Duncan Wilson Timpani Louise Lewis Goodwin

Alto Saxophone Lewis Banks Bassoon Cerys Ambrose-Evans Alison Green

André Cebrián Principal Flute

Percussion Tom Hunter Harp Eleanor Hudson Piano Simon Smith

WHAT YOU ARE ABOUT TO HEAR

Milhaud (1892-1974)

La création du monde (1922–23)

Ouverture: Modéré

Le chaos avant la création

La naissance de la flore et de la faune

La naissance de l’homme et de la femme

Le désir

Le printemps ou l’apaisement

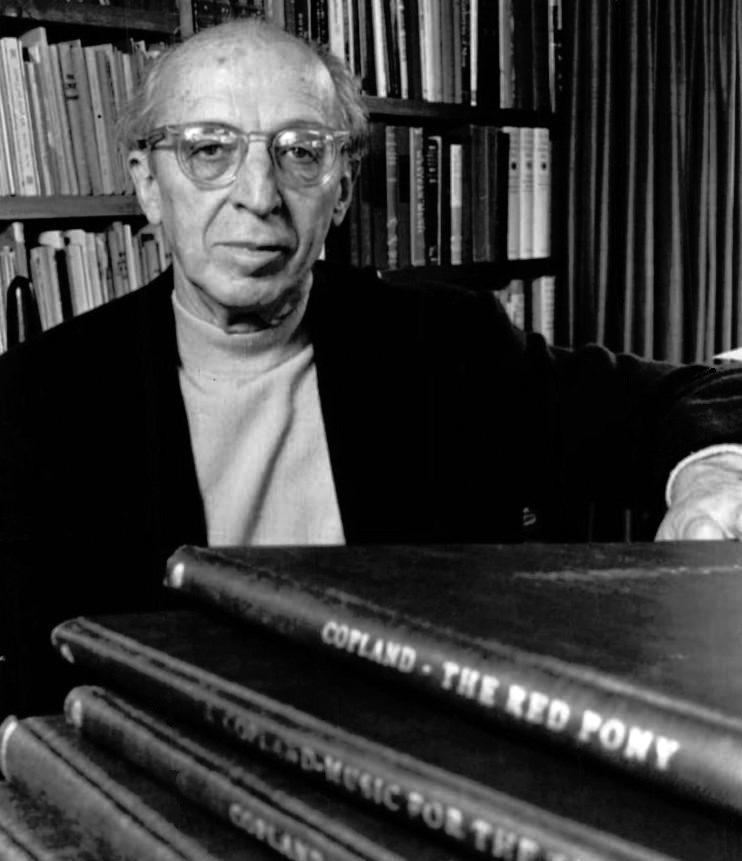

Copland (1900-1990)

Clarinet Concerto (1947–49)

Slowly and expressively

Cadenza

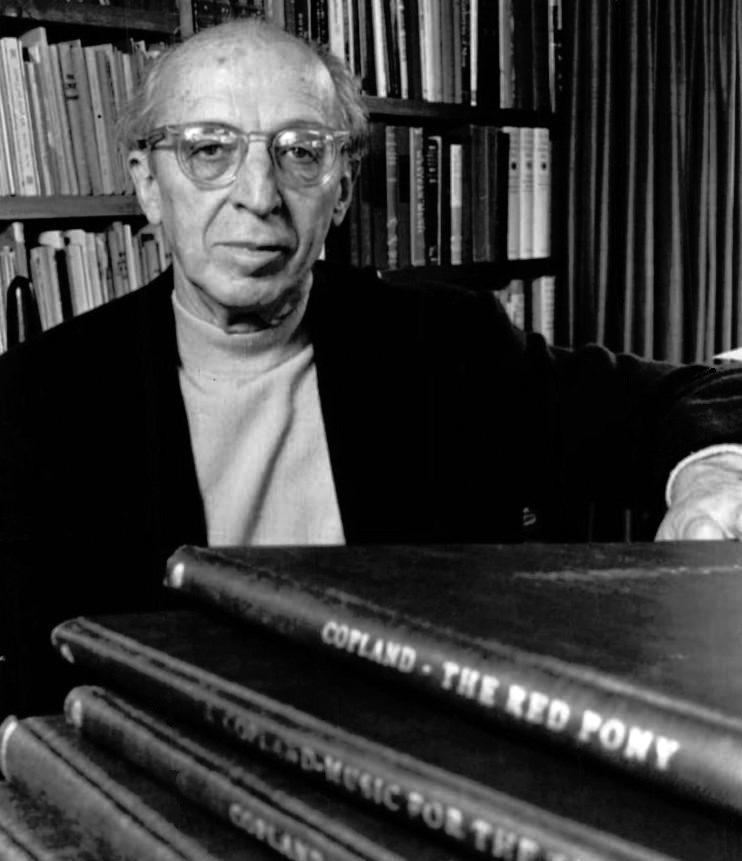

Rather fast Bernstein (1918-1990)

Sonata for Clarinet and Orchestra (1941-2) orch. Ramin (1994)

Poulenc (1899-1963)

Sinfonietta (1947)

Allegro con fuoco

Molto vivace

Andante cantabile

Finale: Prestissimo et très gai

Highbrow or lowbrow, classical or popular: in truth, there’s always been a hazy line between musical styles seen as ‘high’ or ‘low’. Bach composed and performed to entertain listeners in a Leipzig coffee house; both Bartók and Vaughan Williams immersed themselves in their respective countries’ folk music; and in recent years, several rock musicians (step forward Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood and the National’s Bryce Dessner, for starters) have been turning away from stadiums to establish themselves as classical composers.

Back in America in the 1920s, a newfangled style called jazz was starting to become seriously popular – though far from reputable. European composers quickly pricked up their ears, particularly (though not exclusively) those in Paris, whose own artful, playful sophistication – drawing on the music hall and circus as much as the opera house and concert hall – found a friendly playmate in the louche, raucous music emanating from jazz bands across the Atlantic.

Darius Milhaud heard his first live jazz in London in 1920, at a concert from Billy Arnold’s Novelty Jazz Band. He promptly voyaged to New York to check out the new musical style for himself, touring the dance halls and speakeasies of Harlem to do so. When he arrived back in Paris, he discovered to his surprise that jazz had beaten him to it, and was already immensely popular in the French capital, led by the provocative singer and dancer Josephine Baker.

But it didn’t dent the composer’s enduring love for the style. He’d already made a name for himself as a member of loose composer collective Les Six, who aimed

to sweep away the pastel-hued lyricism of impressionism and replace it with something altogether wittier, brighter and more sophisticated. In jazz, Milhaud found the ideal source material.

He wrote La création du monde for a production by the Ballets Suédois (Swedish successors to Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes) in Paris in 1923, with a story by Swiss poet Blaise Cendrars based loosely on pseudoAfrican creation myths, and a set by cubist painter Fernand Léger. It tells of three African gods conjuring trees, animals and humans into being with their magical spells, and concludes with an Adam and Eve-like duo left on stage to mark the beginnings of civilisation.

Milhaud’s colourful score opens almost like a jazzed-up Bach chorale prelude, with a pensive saxophone keening a melody

against restless strings, before the curtain goes up to a bright and sassy fugue, kicked off by double bass and trombone. Just as the counterpoint reaches near delirium, however, the pace suddenly drops for a quieter, almost Gershwin-like episode, though Milhaud’s jazz licks return in the Stravinskian scherzo that follows. All this proves a grand prelude to Milhaud’s mapcap finale, however, which quickly generates its own earworm of a riff – you might find it quite a challenge not to tap your feet. Milhaud signs off, however, with a far quieter, more thoughtful section, almost as if to stand back from the jazzy abandon he’s unleashed.

Leonard Bernstein (we’ll return to him later) was no stranger himself to mixing jazz and classical styles, and he summed up Milhaud’s ballet score succinctly: ‘The Creation of the World emerges not as a flirtation, but as a

He’dalreadymadea nameforhimselfasa memberofloosecomposer collectiveLesSix,who aimedtosweepaway thepastel-huedlyricism ofimpressionismand replaceitwithsomething altogetherwittier,brighter andmoresophisticated. Injazz,Milhaudfoundthe idealsourcematerial.

Darius Milhaud

real love affair with jazz.’ It was a love affair, indeed, that lasted Milhaud’s whole life, and would bring interpenetrating influences full circle. Following the Nazi invasion of France in 1940, Milhaud fled to America. He later taught at Mills College in Oakland and the Music Academy of the West in Montecito, both in California. There, two of his most famous students were Dave Brubeck and Burt Bacharach.

We jump forward almost a quarter of a century – to 1947 – and back across the Atlantic from France for the origins of tonight’s next piece. The Second World War had just ended; hope and optimism were in the air; and one of the biggest stars in popular music approached Aaron Copland to write him a concerto.

As a clarinettist and bandleader, Benny Goodman had been a huge figure in

jazz during the 1930s, and was already an accomplished player of the clarinet masterpieces in the classical repertoire too. No doubt wondering whether the popularity of his particular brand of perky ensemble jazz would survive changing post-war tastes, he eyed a move sideways into classical music in the 1940s.

For his part, Copland had just completed his much-admired Third Symphony, which incorporates his already iconic Fanfare for the Common Man into its expansive finale, and had already marked out his vision of a distinctly American music in his trio of folkinspired ballets Billy the Kid, Rodeo and Appalachian Spring. Nonetheless, he felt it was perhaps time to turn his attention to other musical styles. Goodman’s request could probably not have come at a better moment.

It’sdividedrightdownthe middleintoacool,classical firstmovementandahot, jazzyfinale,withashowy solo cadenza in between slidinggracefullyfrom onestyletotheother.It’s almostasifCoplandset outtoencapsulatewhat he saw as the two facets of Goodman’s own musical personality

Aaron Copland

Copland was partway through a fourmonth lecture tour of South America, funded by the US State Department, when he started work on the Clarinet Concerto, and indeed incorporated a Brazilian tune he’d heard in Rio into the new piece. Things went smoothly until Copland showed Goodman a first draft of the Concerto in 1948, and the clarinettist admitted to not being confident enough in his technical abilities to pull off some of the composer’s more virtuosic demands. Copland made a few adjustments, but retained his original version, too, marking the ending of the piece somewhat acidly: ‘1st version – later revised – of Coda of Clarinet Concerto (too difficult for Benny Goodman)’.

If we return to our original theme of classical and popular styles, the unusual, two-movement form of Copland’s Clarinet Concerto provides the ideal setting in which to consider both sides. It’s divided right down the middle into a cool, classical first movement and a hot, jazzy finale, with a showy solo cadenza in between sliding gracefully from one style to the other. It’s almost as if Copland set out to encapsulate what he saw as the two facets of Goodman’s own musical personality, or indeed the clarinet’s, in his two contrasting movements.

The composer described his first movement as having a ‘bittersweet lyricism’ (he predicted: ‘I think this will make everyone weep’). In its evocation of wide, open spaces, it feels very much like a continuation of his trio of American ballets: his clarinettist sings their stately melody amid a vast, open landscape surveyed by the strings. Copland’s helterskelter second movement, however, couldn’t provide a starker contrast.

Freely colliding jazz and popular styles from North and South America, it grows increasingly raucous as it rushes towards its close – with what can only be an overt tribute to Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue as its final gesture.

We return to that great straddler of popular and classical styles, Leonard Bernstein, for tonight’s next piece. He was technically still a student when he wrote his Clarinet Sonata in 1941, immersing himself in the hothouse teaching at Massachusetts’s Tanglewood summer school, which Serge Koussevitzky had established a few years earlier. Bernstein learnt all he could from the eminent conductor, also mingling with his friend and mentor Copland, senior composer Paul Hindemith, and young clarinettist David Oppenheim, the Sonata’s dedicatee, who became a close friend.

The Sonata ended up as Bernstein’s very first work to be published, and coincidentally follows a similar twomovement format to that of Copland’s Clarinet Concerto. Even in its barely ten-minute span, however, the Sonata already encapsulates the central issue that would preoccupy so much of the music that Bernstein produced: the apparently unresolvable collision between cool, intellectual rigour and hot-headed, warmhearted, jazzy fun.

Hindemith clearly exerted quite a heavy influence on Bernstein’s writing in the Sonata (even Copland declared the work to be ‘full of Hindemith’), most obviously in its cool, not-quite-atonal opening melody, whose disarming combination of lyricism and detachment could come straight from an undiscovered sonata by

the great German émigré. But Bernstein contrasts that aloofness with driving, almost minimalist rhythms accompanying his second theme, and lets rip further with the irregular dance beats of his sprightly, Latin-infused second movement. The tranquil, ruminative opening to his second movement functions almost as a miniature slow movement in itself. Listen carefully to it, and you’ll even hear a distinctive twochord piano figure that Bernstein would later use to great effect in ‘Somewhere’ from West Side Story.

We leap back across the Atlantic to France for tonight’s final piece, which embodies another precarious balance between serious art and popular fun. Francis Poulenc was no stranger to wit, sparkle and jazzy inspirations in his music (he was a signed-up member of Les Six alongside his partner in crime and confidant Darius

Milhaud). But by 1947, the year he wrote his Sinfonietta, he was aiming for a slightly cooler, more serious approach. Like Copland’s Clarinet Concerto, Poulenc’s Sinfonietta rode the wave of optimism following the end of the Second World War. It was commissioned by the BBC to celebrate the first anniversary of the Third Programme, predecessor to BBC Radio 3, as one of several works marking the new-found freedom of continental Europe following the conflict.

Poulenc never wrote a symphony, but his Sinfonietta (literally ‘little symphony’) is probably the closest he came. Indeed, it’s almost as if he stepped back from using that high-flown term for this energetic, light-hearted music, though he generally toned down his high spirits in it. Once he’d finished the work, the then 48-year-old composer admitted

to being

The Sonata already encapsulates the central issue that would preoccupy so much of the music that Bernstein produced: the apparently unresolvable collision between cool, intellectual rigour and hot-headed, warm-hearted, jazzy fun.

Leonard Bernstein

rather surprised himself at the gleeful wit and high spirits that remained in his Sinfonietta, and to being worried that he might have ‘dressed too young for my years’.

Though it might not be called a symphony, the Sinfonietta falls into the conventional four movements we might expect to find in that musical form. A burst of frantic energy kicks off its first movement, though its zingy vivacity gradually dissipates as the movement progresses. And rather than following the tight structure of contrasting themes in a traditional symphonic first movement, Poulenc is instead content to offer a succession of contrasting episodes. He seems to pay tribute to favourite fellow composers in his bustling second movement scherzo – Tchaikovsky’s 'Pathétique' Symphony, or Mendelssohn’s fairy music, or even Mozart – and his

slow third movement achieves an almost Mahlerian intensity at times.

There’s no mistaking the influence of Stravinsky in his witty, dashing finale. (Poulenc himself admitted as much, saying: ‘I know very well that I am not the sort of musician who makes harmonic innovations, like Stravinsky, Ravel or Debussy, but I do think there is a place for new music that is satisfied with using other people’s chords.’) But we make a notable return, too, to popular music, in this case sounds that seem to come directly from the music hall, in themes that Poulenc reworked from an early string quartet he’d abandoned. He was forced, however, to reconstruct that music from memory: he felt the original work had failed so badly that he’d flung its score into a Parisian sewer.

© David Kettle

© David Kettle

Poulenc’sSinfonietta rodethewaveofoptimism followingtheendofthe SecondWorldWar... asoneofseveralworks markingthenew-found freedomofcontinental Europefollowingthe conflict.

Francis Poulenc

Conductor JOSEPH SWENSEN

Joseph Swensen is Artistic Director of the NFM Leopoldinum Orchestra (Wroclaw), Principal Guest Conductor of the Orquesta Ciudad de Granada and Conductor Emeritus of the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. He has previously served as Principal Guest Conductor & Artistic Adviser of the Orchestre de Chambre de Paris (2009-2012), Principal Conductor of the Scottish Chamber Orchestra (1996-2005) and Principal Conductor of Malmö Opera (2005-2011). Recognized for forging solid bonds with orchestras, 2019-20 also includes returns to Swensen’s closest guestconducting partners, the Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse and Orquestra Sinfónica do Porto Casa da Música, as well as re-invitations from BBC National Orchestra of Wales and Orquesta Sinfónica de Navarra.

A multifaceted musician, Joseph Swensen is an active composer and orchestrator. His orchestration of Prokofiev’s Five Songs Without Words (1920) is published by Boosey and Hawkes and Signum recorded Sinfonia in B (2007), an orchestration of the rarely performed 1854 version of Brahms’ Trio Op 8. His work also includes orchestrations of Nielsen Quartet in G minor, Four Movements for Orchestra (1888) as well as arrangements for string orchestras of Beethoven String Quartet op 131 and Debussy String Quartet, which he recorded with the NFM Leopoldinum. His most notable compositions include Shizue (2001) for solo shakuhachi and orchestra, and the Sinfonia-Concertante for Horn and Orchestra (The Fire and the Rose) (2008) as well as Sinfonietta (2017) for strings and synthesizer.

A sought-after pedagogue, Joseph Swensen teaches conducting, violin and chamber music at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland in Glasgow.

An American of Norwegian and Japanese descent, Joseph Swensen was born in Hoboken, New Jersey and grew up in Harlem, New York City.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

Joseph's Chair is kindly supported by Donald and Louise MacDonald

MAXIMILIANO MARTÍN

Spanish Clarinettist and international soloist Maximiliano Martín is one of the most exciting and charismatic musicians of his generation. He combines his position of Principal Clarinet of the SCO with solo, chamber music engagements and masterclasses all around the world.

Maximiliano has appeared as a soloist and chamber musician in many of the world's most prestigious venues including the BBC Proms at Cadogan Hall, Wigmore Hall, Library of Congress in Washington, Mozart Hall in Seoul, Laeiszhalle Hamburg, Durban City Hall in South Africa, and Teatro Monumental in Madrid. Highlights of the past years have included concertos with the SCO, European Union Chamber Orchestra, and Orquesta Filarmónica de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, amongst others. He performs regularly with ensembles and artists such as London Conchord Ensemble, Doric and Casals String Quartets, François Leleux, Pekka Kuusisto and Llŷr Williams.

He is one of the Artistic Directors of the Chamber Music Festival of La Villa de La Orotava, held every year in his hometown. Maximiliano Martín is a Buffet Crampon Artist and plays with Buffet Tosca Clarinets.

Born in La Orotava (Tenerife), he studied at the Conservatorio Superior de Musica in Tenerife, Barcelona School of Music and at the RCM, where he held the prestigious Wilkins-Mackerras Scholarship, graduated with distinction and received the Frederick Thurston prize. His teachers have included Joan Enric Lluna, Richard Hosford and Robert Hill. Martín was a prize-winner in the Howarth Clarinet Competition of London and at the Bristol Chamber Music International Competition.

Maximiliano's Chair is kindly supported by Stuart and Alison Paul

Clarinet

Biography SCOTTISH CHAMBER ORCHESTRA

The internationally celebrated Scottish Chamber Orchestra is one of Scotland’s National Performing Companies.

Formed in 1974 and core funded by the Scottish Government, the SCO aims to provide as many opportunities as possible for people to hear great music by touring the length and breadth of Scotland, appearing regularly at major national and international festivals and by touring internationally as proud ambassadors for Scottish cultural excellence.

Making a significant contribution to Scottish life beyond the concert platform, the Orchestra works in schools, universities, colleges, hospitals, care homes, places of work and community centres through its extensive Creative Learning programme. The SCO is also proud to engage with online audiences across the globe via its innovative Digital Season.

An exciting new chapter for the SCO began in September 2019 with the arrival of dynamic young conductor Maxim Emelyanychev as the Orchestra’s Principal Conductor.

The SCO and Emelyanychev released their first album together (Linn Records) in November 2019 to widespread critical acclaim. The repertoire - Schubert’s Symphony No. 9 in C major ‘The Great’ –is the first symphony Emelyanychev performed with the Orchestra in March 2018.

The SCO also has long-standing associations with many eminent guest conductors including Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen, François Leleux, Pekka Kuusisto, Richard Egarr, Andrew Manze and John Storgårds.

The Orchestra enjoys close relationships with many leading composers and has commissioned almost 200 new works, including pieces by the late Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, Sir James MacMillan, Sally Beamish, Martin Suckling, Einojuhani Rautavaara, Karin Rehnqvist, Mark-Anthony Turnage, Nico Muhly, Anna Clyne and Associate Composer Jay Capperauld.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

CONCERTS SEASON 22/23

MUSIQUE AMÉRIQUE

Kindly supported by SCO American Development Fund

12-13 Jan, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

AN EVENING WITH FRANÇOIS LELEUX

Our Edinburgh concert is sponsored by Institut Français Écosse 19-21 Jan, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow | Aberdeen

MÖDER DY / MOTHER WAVE

Part of Celtic Connections 2023 26-27 Jan, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow MOZART’S FLUTE CONCERTO 15-17 Feb, 7.30pm St Andrews | Edinburgh | Glasgow

MAXIM CONDUCTS BRAHMS 23-24 Feb, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

THE DREAM

Sponsored by Pulsant 2-4 Mar, 7.30pm Perth | Edinburgh | Glasgow

FOLK INSPIRATIONS

WITH PEKKA

9-10 Mar, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

LES ILLUMINATIONS

15-17 Mar, 7.30pm St Andrews | Edinburgh | Glasgow

HANDEL: MUSIC FOR THE ROYALS

Our Edinburgh concert is kindly supported by The Usher Family 23-24 Mar, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

SCHUBERT’S UNFINISHED SYMPHONY

Kindly supported by Claire and Mark Urquhart 30 Mar-1 Apr, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow | Aberdeen

SUMMER NIGHTS

WITH KAREN CARGILL

19-21 Apr, 7.30pm St Andrews | Edinburgh | Glasgow

BEETHOVEN’S FIFTH

27-29 Apr, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow | Aberdeen

TCHAIKOVSKY’S FIFTH

4-5 May, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

BRAHMS REQUIEM

11-12 May, 7.30pm Edinburgh | Glasgow

4 Royal Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 5AB +44 (0)131 557 6800 sco.org.uk

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra is a charity registered in Scotland No. SC015039. Company registration No. SC075079.

SCO.ORG.UK Find us on

AN EVENING WITH FRANÇOIS LELEUX 19-21 Jan, 7.30pm, Edinburgh | Glasgow | Aberdeen François Leleux Conductor/Oboe INCLUDING MUSIC BY FARRENC, MENDELSSOHN and SCHUBERT 18 and Under FREE BOOK NOW SCO.ORG.UK Company Registration Number: SC075079. A charity registered in Scotland No. SC015039. Our Edinburgh concert is Sponsored by

WE BUILD RELATIONSHIPS THAT LAST GENERATIONS.

Generations of our clients have trusted us to help build and preserve their wealth.

For over 250 years, they have relied on our expert experience to help make sense of a changing world. During that time we’ve earned an enviable reputation for a truly personal approach to managing wealth.

For those with over £250,000 to invest we o er a dedicated investment manager, with a cost structure and level of service, that generates exceptional client loyalty.

Find out more about investing with us today: Murray Clark at our Edinburgh o ce on 0131 221 8500, Gordon Ferguson at our Glasgow o ce on 0141 222 4000 or visit www.quiltercheviot.com

INVESTING FOR GENERATIONS

Investors should remember that the value of investments, and the income from them, can go down as well as up and that past performance is no guarantee of future returns. You may not recover what you invest. Quilter Cheviot and Quilter Cheviot Investment Management are trading names of Quilter Cheviot Limited. Quilter Cheviot Limited is registered in England with number 01923571, registered o ce at Senator House, 85 Queen Victoria Street, London, EC4V 4AB. Quilter Cheviot Limited is a member of the London Stock Exchange and authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority.

BE PART OF OUR FUTURE

A warm welcome to everyone who has recently joined our family of donors, and a big thank you to everyone who is helping to secure our future.

Monthly or annual contributions from our donors make a real difference to the SCO’s ability to budget and plan ahead with more confidence. In these extraordinarily challenging times, your support is more valuable than ever.

For more information on how you can become a regular donor, please get in touch with Mary Clayton on 0131 478 8369 or email mary.clayton@sco.org.uk.

The SCO is a charity registered in Scotland No SC015039.

SCO.ORG.UK/SUPPORT-US

Delivered by

Delivered by

© David Kettle

© David Kettle