Wednesday 24 April, 7.30pm, Perth Concert Hall

Thursday 25 April, 7.30pm, The Queen's Hall, Edinburgh

Friday 26 April, 7.30pm, City Halls, Glasgow

HONEGGER Pastorale d’été

RAVEL Piano Concerto in G

Interval of 20 minutes

RAVEL Pavane pour une infante défunte

HAYDN Symphony No 87

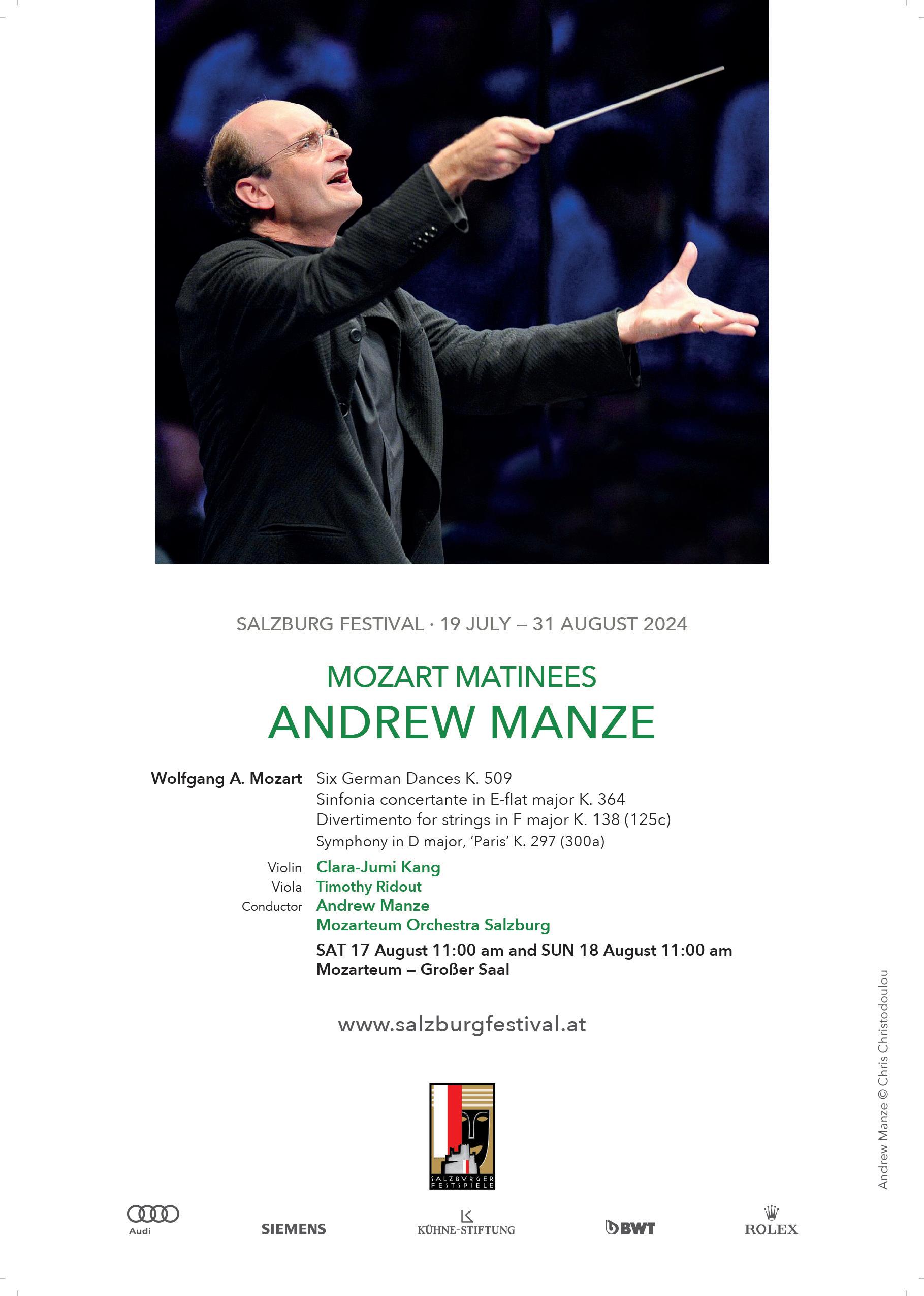

Andrew Manze Conductor

Steven Osborne Piano

4 Royal Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 5AB +44 (0)131 557 6800 | info@sco.org.uk | sco.org.uk

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra is a charity registered in Scotland No. SC015039. Company registration No. SC075079.

Our Principal Conductor’s Circle are a special part of our musical family. Their commitment and generosity benefit us all – musicians, audiences and creative learning participants alike.

Annual Fund

James and Patricia Cook

Visiting Artists Fund

Colin and Sue Buchan

Harry and Carol Nimmo

Anne and Matthew Richards

International Touring Fund

Gavin and Kate Gemmell

Creative Learning Fund

Sabine and Brian Thomson

CHAIR SPONSORS

Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen

Donald and Louise MacDonald

Chorus Director Gregory Batsleer

Anne McFarlane

Principal Second Violin

Marcus Barcham Stevens

Jo and Alison Elliot

Second Violin Rachel Smith

J Douglas Home

Principal Viola Max Mandel

Ken Barker and Martha Vail Barker

Viola Brian Schiele

Christine Lessels

Viola Steve King

Sir Ewan and Lady Brown

Principal Cello Philip Higham

The Thomas Family

American Development Fund

Erik Lars Hansen and Vanessa C L Chang

Productions Fund

Bill and Celia Carman

Anny and Bobby White

Anne, Tom and Natalie Usher

Scottish Touring Fund

Eriadne and George Mackintosh

Claire and Anthony Tait

Cello Donald Gillan

Professor Sue Lightman

Cello Eric de Wit

Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund

Principal Double Bass Nikita Naumov

Caroline Hahn and Richard Neville-Towle

Principal Flute André Cebrián

Claire and Mark Urquhart

Principal Oboe Robin Williams

In memory of Hedley G Wright

Principal Clarinet Maximiliano Martín

Stuart and Alison Paul

Principal Bassoon Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Claire and Anthony Tait

Principal Timpani Louise Lewis Goodwin

Geoff and Mary Ball

Diamond

Malcolm and Avril Gourlay

John and Jane Griffiths

James and Felicity Ivory

Robin and Catherine Parbrook

Clair and Vincent Ryan

William Samuel

Tom and Natalie Usher

Platinum

David Caldwell in memory of Ann

Judith and David Halkerston

Audrey Hopkins

David and Elizabeth Hudson

Dr and Mrs Peter Jackson

Dr Daniel Lamont

Chris and Gill Masters

Duncan and Una McGhie

Anne-Marie McQueen

James F Muirhead

Patrick and Susan Prenter

Mr and Mrs J Reid

George Ritchie

Martin and Mairi Ritchie

Hilary E Ross

Elaine Ross

George Rubienski

Jill and Brian Sandford

Michael and Elizabeth Sudlow

Robert and Elizabeth Turcan

Alan and Sue Warner

Finlay and Lynn Williamson

Dr Peter Williamson and Ms Margaret Duffy

Ruth Woodburn

William Zachs

Gold

John and Maggie Bolton

Kate Calder

Lord Matthew Clarke

Jo and Christine Danbolt

James and Caroline Denison-Pender

Andrew and Kirsty Desson

David and Sheila Ferrier

Chris and Claire Fletcher

Dr J W E Forrester

James Friend

Adam Gaines and Joanna Baker

Margaret Green

Iain Gow

Christopher and Kathleen Haddow

Catherine Johnstone

Gordon Kirk

Robert Mackay and Philip Whitley

Mike and Karen Mair

Anne McAlister and Philip Sawyer

Roy and Svend McEwan-Brown

John and Liz Murphy

Maggie Peatfield

Charles Platt

Alison and Stephen Rawles

Andrew Robinson

Olivia Robinson

Irene Smith

Ian S Swanson

John-Paul and Joanna Temperley

James Wastle and Glenn Craig

Bill Welsh

Catherine Wilson

Neil and Philippa Woodcock

G M Wright

Bruce and Lynda Wyer

Silver

Roy Alexander

Pamela Andrews and Alan Norton

Dr Peter Armit

William Armstrong

Fiona and Neil Ballantyne

Timothy Barnes and Janet Sidaway

The Batsleer Family

Jack Bogle

Jane Borland

Alan Borthwick

Michael and Jane Boyle

Mary Brady

Elizabeth Brittin

John Brownlie

Laura Buist

Robert Burns

Sheila Colvin

Lorn and Camilla Cowie

Philip Croft and David Lipetz

Lord and Lady Cullen of Whitekirk

Adam and Lesley Cumming

Dr Wilma Dickson

Sylvia Dow

Dr and Mrs Alan Falconer

Sheila Ferguson

Malcolm Fleming

Dr William Irvine Fortescue

Dr David Grant

Andrew Hadden

J Martin Haldane

Ronnie and Ann Hanna

Ruth Hannah

Robin Harding

Roderick Hart

Norman Hazelton

Ron and Evelynne Hill

Philip Holman

Clephane Hume

Tim and Anna Ingold

David and Pamela Jenkins

Susannah Johnston and Jamie Weir

Julie and Julian Keanie

Marty Kehoe

Professor Christopher and Mrs Alison Kelnar

Dr and Mrs Ian Laing

Janey and Barrie Lambie

Graham and Elma Leisk

Geoff Lewis

Dorothy A Lunt

Vincent Macaulay

James McClure in memory of Robert Duncan

Gavin McCrone

Brian Miller

James and Helen Moir

Alistair Montgomerie

Margaret Mortimer and Ken Jobling

Andrew Murchison

Hugh and Gillian Nimmo

David and Tanya Parker

Hilary and Bruce Patrick

John Peutherer in memory of Audrey Peutherer

James S Potter

Alastair Reid

Fiona Reith

Catherine Steel

Ian Szymanski

Takashi and Mikako Taji

Douglas and Sandra Tweddle

C S Weir

We are indebted to everyone acknowledged here who gives philanthropic gifts to the SCO of £300 or greater each year, as well as those who prefer to remain anonymous.

We are also incredibly thankful to the many individuals not listed who are kind enough to support the Orchestra financially on a regular or ad hoc basis. Every single donation makes a difference.

Become a regular donor, from as little as £5 a month, by contacting Hannah Wilkinson on 0131 478 8364 or hannah.wilkinson@sco.org.uk.

“A crack musical team at the top of its game.”

HRH The Former Duke of Rothesay

Patron

Donald MacDonald CBE Life President

Joanna Baker CBE

Chair

Gavin Reid LVO Chief Executive

Maxim Emelyanychev Principal Conductor

Andrew Manze Principal Guest Conductor

Joseph Swensen Conductor Emeritus

Gregory Batsleer Chorus Director

Jay Capperauld Associate Composer

Information correct at the time of going to print

First Violin

Johnny Gandelsman

Afonso Fesch

Stephanie Baubin

Kana Kawashima

Aisling O’Dea

Siún Milne

Fiona Alexander

Amira Bedrush-McDonald

Second Violin

Marcus Barcham Stevens

Gordon Bragg

Rachel Smith

Sarah Bevan Baker

Niamh Lyons

Catherine James

Viola

Max Mandel

Francesca Gilbert

Brian Schiele

Steve King

Cello

Philip Higham

Su-a Lee

Donald Gillan

Eric de Wit

Bass

Jamie Kenny

Toby Hughes

Flute

André Cebrián

Marta Gómez

Piccolo

Marta Gómez

Oboe

Robin Williams

Katherine Bryer

Cor Anglais

Katherine Bryer

Clarinet

Maximiliano Martín

William Stafford

E Flat Clarinet

William Stafford

Bassoon

Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Alison Green

Horn

George Strivens

Jamie Shield

Helena Jacklin

Trumpet

Peter Franks

Trombone

Duncan Wilson

Timpani

Louise Lewis Goodwin

Percussion

Tom Hunter

Alasdair Kelly

Kate Openshaw

Harp

Eleanor Hudson

Louise Lewis Goodwin

Timpani / Percussion

HONEGGER (1892-1955)

Pastorale d’été (1920)

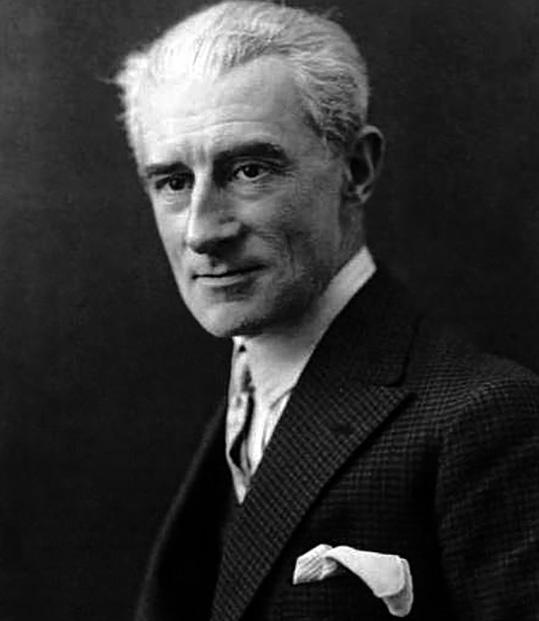

RAVEL (1875-1937)

Piano Concerto in G major (1929–31)

I. Allegramente

II. Adagio assai

III. Presto

RAVEL (1875-1937)

Pavane pour une infante défunte (1899)

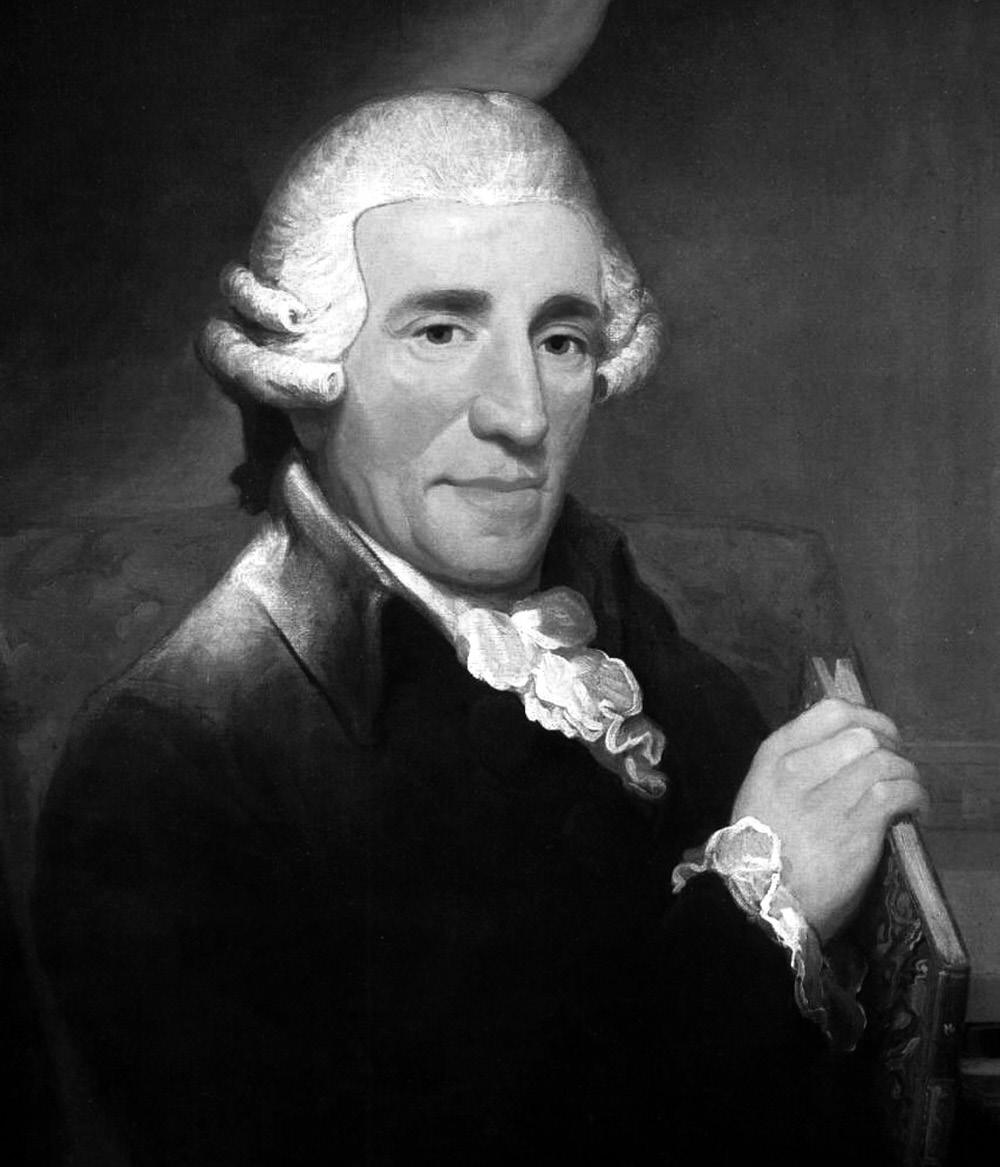

HAYDN (1732-1809)

Symphony No 87 in A major (1786)

I. Vivace

II. Adagio

III. Menuet e trio

IV. Finale vivace

Paris is the city that brings together all four of the contrasting pieces in tonight’s colourful concert – very directly in the case of two of them, more obliquely with the others.

Arthur Honegger might have been born in Le Havre on the English Channel, and he might have maintained strong lifelong links with his parents’ homeland of Switzerland, but he spent almost his entire career in the French capital. He studied at the Paris Conservatoire (with high-profile composers Charles-Marie Widor and Vincent d’Indy), and Parisian venues hosted the premieres of many of the early pieces that brought him to prominence.

And it was in the Parisian apartment of fellow composer Darius Milhaud – in the well-heeled 17th arrondissement, a short walk from the Arc de Triomphe – that Honegger found himself lumped together with a gaggle of other musicians, in January 1920, as part of a brand a new artistic movement. Milhaud had invited Honegger and fellow composers Francis Poulenc, Germaine Tailleferre, Georges Auric and Louis Durey for an exclusive private recital evening that would feature one work by each of them. Among his other guests, he’d also invited sympathetic journalist Henri Collet, who in his write-up in the newspaper Comoedia christened those composers ‘Les Six’.

In fairness, Honegger always stood somewhat apart from the wit, irony and general jokiness of some of his colleagues in that informal grouping: his music was more serious, more sincere, even quite a bit more challenging. It’s hard to imagine Milhaud or Poulenc, for example, coming up with anything like Honegger’s most famous

Arthur Honegger

Arthur Honegger

work: Pacific 231 is a musical depiction of a giant steam locomotive, a celebration of mechanisation and raw power.

But Collet’s article nonetheless brought Honegger plenty of attention in early 1920 – so much so, in fact, that the composer felt he needed to get away from the buzz and busyness of Paris, and retreat to the Swiss Alps for a bit of him-time. It was there – in August 1920, in the resort village of Wengen, nestling beneath the Eiger and the Jungfrau – that Honegger wrote tonight’s first piece, Pastorale d’été

He prefaced his score with the opening line from Aube by the radical French poet Arthur Rimbaud: ‘J’ai embrassé l’aube de l’été’. It’s usually translated as the rather restrained ‘I embraced the summer dawn’, but there’s a more intimate, more sensual sense of having actually kissed the sunrise. Whatever Rimbaud’s line might imply, the piece isn’t really about a musical dawn at all. Instead,

Honegger always stood somewhat apart from the wit, irony and general jokiness of some of his colleagues in that informal grouping: his music was more serious, more sincere, even quite a bit more challenging.

it’s more a portrait of calm serenity high in the mountains – one in which Honegger nonetheless reflects Rimbaud’s sensuous description in music that’s rich, opulent and languid.

The orchestra’s strings set up a gently undulating accompaniment that quickly ushers in a long, slow horn melody. (You might even detect a certain bluesiness to those opening harmonies and tune: jazz and blues were all the rage in Parisian clubs at the time, as Honegger was more than aware – and we’ll hear a lot more of them in tonight’s next piece.) An oboe takes over that opening melody, accompanied by birdsong from the flute and clarinet, and there’s a sudden shift in harmony to something even more voluptuous before the bassoon heralds a brighter section with a distinctly folksy feel, sharing melodic duties with the clarinet. After a while, however, it feels like all that activity gets a bit too much, and the piece slows for a

return of the opening music, and a slow slide into a quiet, teasingly inconclusive conclusion.

Like Honegger, Maurice Ravel spent the majority of his life in Paris, though he was born in the Basque country on the Atlantic coast, in Ciboure, just a stone’s throw from the Spanish border. His beloved mother was Basque, and she’d grown up in Madrid (but we’ll return to Ravel’s Spanish connections shortly). By the time Ravel came to write his Piano Concerto in G in 1931, he was well established as a fine pianist and a fastidious composer.

It was following an enormously successful concert tour of America in 1928 that Ravel came up with the idea of writing a Piano Concerto – for himself to play, naturally, and as the centrepiece of an even grander return tour. But those projected stateside performances were not to be. For a start, the Concerto took him two years to write – he was already a notoriously slow composer, but he was also distracted by the simultaneous composition of his far darker Piano Concerto for the Left Hand, commissioned by pianist Paul Wittgenstein who’d lost his right arm in the First World War. Nearing the deadline, Ravel wrote: ‘I can’t manage to finish my Concerto, so I’m resolved not to sleep for more than a second. When my work is finished I shall rest in this world… or the next!’ Those were prophetic words: the Piano Concerto in G was Ravel’s last major work, his gradual decline in health also contributing to the slowness of its composition.

When it came to performing the piece, the increasingly ailing Ravel found his strength and skills were not up to the task. Instead, he dedicated the Concerto to the

eminent French pianist Marguerite Long, and offered her the first performance. She gladly accepted, later calling the piece ‘a work of art in which fantasy, humour and the picturesque frame one of the most touching melodies that has come from the human heart’. The hugely successful premiere was in Paris in January 1932, with Ravel conducting the Orchestre Lamoureux, and led to more than 20 repeat performances throughout Europe, where the Concerto was received equally enthusiasically.

Quintessentially French in its craftsmanship, lyricism, gracefulness and wit, the Piano Concerto in G is also heavily influenced by the then new-fangled jazz, which Ravel had encountered on his 1928 US tour – and arguably also by the Spanish folksongs sung to him by his Basque mother.

The first movement opens with a whipcrack and a perky tune on piccolo (perhaps Basque, although Ravel said it came to him on a train from Oxford to London), later taken over by trumpet. But despite some propulsive accompaniment figures, the piano only makes its presence properly felt with the sultry, bluesy second main theme – which sounds uncannily like Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue at times. The soloist segues into a more lyrical, romantic melody, then jumps unexpectedly into a brisk, rhythmic section. When the Basque/London-Oxford tune returns, it’s assertively on the piano, and the bluesy theme is then expanded to grotesque, fantastical proportions, sliding trombones and hammered piano contrasting with a mystical episode for gently chiming harp. After an inexorable build-up, the movement ends with some spiky brass chords.

The slow second movement is where we hear the melody that Marquerite Long so admired – and following her praise, Ravel replied: ‘That flowing phrase! How I worked over it bar by bar! It nearly killed me!’ The movement can be summed up very simply: a long, slow melody that seems to stretch to infinity for solo piano, then a darker, more dissonant central section, and lastly a return of the long opening melody on cor anglais, with discreet decoration from the piano soloist. But to be so blunt is to ignore the exceptional craftsmanship that went into the movement, and the aching poignancy of the tune that caused Ravel so much effort.

The brief, virtuosic third movement is often repeated as an encore after the Concerto – and that may be precisely what Ravel intended. It opens with a call to attention on brass and snare drum, launching into a bubbling piano part that’s interrupted by shrieks and howls from the woodwind, rushing through several characterful

‘I can’t manage to finish my Concerto, so I’m resolved not to sleep for more than a second. When my work is finished I shall rest in this world… or the next!’

interludes before its distinctive opening chords round the Concerto off with a thud.

We leap from the very end of Ravel’s career back to the beginning for tonight’s next piece. He wrote Pavane pour une infante défunte, originally as a piano piece, in 1899 while he was still studying with Gabriel Fauré at the Paris Conservatoire. Its dedicatee, though, was another important figure in the young Ravel’s life. The Princesse de Polignac – née Winnaretta Singer – was the fabulously wealthy, US-born, Paris-based heiress to the Singer sewing machine fortune, and a committed patron of the arts. Ravel used his Pavane pour une infante défunte as a calling card at his first visit to her fashionable salon in Paris’ up-market 16th arrondissement, offering her a score and explaining his dedication of the piece to her. Delighted, the Princesse became one of Ravel’s most passionate early supporters. He, in turn, was able to hobnob with Paris’ cultural elite at her luxurious lodgings, which did his early

Maurice Ravelcareer no harm at all. Though the Pavane must have been heard several times at the Princesse’s invite-only soirées, it was only its public premiere – given by Ravel’s close friend Ricardo Viñes in 1902 – that put it, and Ravel, on the musical map. The composer acknowledged its enduring popularity in reworking the piece for orchestra in 1910.

For a brief, uncomplicated piece, however, the Pavane has caused a certain degree of confusion. Just who was the Spanish infanta of its title, and why had she died? The gentle poignancy of Ravel’s music might well lead you to believe that it’s a funeral ode to a young royal who passed away tragically young, but it’s nothing of the sort. Ravel explained that his infanta was ‘défunte’ simply because she’d lived a long time previously, describing his music as ‘an evocation of a pavane that a little princess might, in former times, have danced at the Spanish court’. Nor is there, despite Ravel’s own strong Spanish connections, very much that’s particularly Iberian in the music. He later admitted that we shouldn’t set too much store by the piece’s title anyway: ‘Do not be surprised – that title has nothing to do with the composition. I simply liked the sound of those words and I put them there: that’s all.’

In a way that might remind you of Honegger’s Pastorale d’été, Ravel begins with a melody for solo horn, this time against gently tick-tocking accompaniment from the strings. It’s answered by a more plangent melody from the oboe, before the original melody returns in flutes and clarinets. A lighter, quicker section introduced by the flute brings contrast, and also the piece’s most overtly emotional music, before a return from the opening theme, now more lavishly scored with rippling harp

accompaniment. Ravel closes, however, with a bare, stark harmony, and ghostly harmonics from the strings, as if a vision is floating to us from the distant past.

So far we’ve experienced two composers and three pieces, all with strong Parisian connections. But – Joseph Haydn? Well, yes, him too. For his Symphony No 87, however, we need to jump back in time more than a century from Ravel’s poignant Pavane, to 1787.

Haydn had been working as a court musician exclusively for the fabulously wealthy Esterházy family at far-flung Eszterháza Palace in what’s now Hungary since 1761. But in 1779, Prince Nikolaus allowed the composer to write music for others, and even to publish his pieces. Haydn had been quietly making his own genredefining musical innovations during those years – establishing the symphony and string quartet as musical forms virtually singlehandedly, for example – but this change of relationship suddenly provided him with entirely new freedoms. And as a result, Haydn’s first major international commission came from Paris.

The Count d’Ogny was a French nobleman and arts patron, and he had co-founded the Concert de la Loge Olympique in 1780 as an orchestra to rival any in the French capital –and with players decked out in sky blue dress coats and flamboyant ruffles, with swords swinging by their sides, it quickly made its mark. A key part of the Concert’s impact, though, came from its sheer size: it’s reported to have run to no fewer than 65 musicians, creating a sonic richness almost unheard of at the time (by way of comparison, Haydn had had to be content with a ensemble of fewer than 25 at Eszterháza).

Haydn had been quietly making his own genre-defining musical innovations during those years – establishing the symphony and string quartet as musical forms virtually single-handedly, for example – but this change of relationship suddenly provided him with entirely new freedoms.

When Haydn received a commission for six new symphonies from d’Ogny – via the Concert’s celebrated conductor Joseph Bologne, the Chevalier de Saint-Georges – no wonder he jumped at the chance. His decision was no doubt helped by the sizeable fee of 25 Louis d’or he was offered for each of the six symphonies he’d compose. (Mozart, by contrast, had received a measly five Louis d’or for his own ‘Paris’ Symphony a few years earlier.)

His Symphony No 87 – the last of Haydn’s own ‘Paris’ Symphonies – was actually the first of them that he composed, probably in 1785. But its air of sunny celebration and festivity makes it an ideal work to close the set. Haydn dispenses with his customary slow introduction, launching straight into his first movement’s dashing, surging main theme. Just listen to how many repeated notes he employs, in both melodies and accompaniments: no wonder the music conveys a sense of relentless power and

movement, an energy that continues into his second main melody. Daring harmonic explorations abound in the central development section, which also includes a moment when the music literally stops in its tracks, before launching off again as if nothing has happened.

His second movement combines hushed, prayerful music from the strings and horns with a sumptuously decorated melodic line from the flute, and, despite a few stormy moments, retains a sense of elegance and quiet beauty throughout. The third movement is quite a heavy-footed minuet, with a perky oboe tune leading into its calmer central trio section. Those repeated notes from the first movement return in the propulsive bassline of the finale, supporting an eager, bouncing opening tune that pushes the movement to a resplendent conclusion.

© David Kettle Franz Joseph Haydn

Andrew Manze is widely celebrated as one of the most stimulating and inspirational conductors of his generation. His extensive and scholarly knowledge of the repertoire, together with his boundless energy and warmth, mark him out. He held the position of Chief Conductor of the NDR Radiophilharmonie in Hannover from 2014 until 2023. Since 2018, he has been Principal Guest Conductor of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra.

In great demand as a guest conductor across the globe, Manze has long-standing relationships with many leading orchestras, and in the 23/24 season will return to the Royal Concertgebouworkest, the Munich Philharmonic, Rotterdam Philharmonic, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Bamberg Symphoniker, Oslo Philharmonic, Finnish Radio, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Mozarteum Orchester Salzburg, RSB Berlin, and the Dresden Philharmonic among others, and will lead the Chamber Orchestra of Europe in their tour of Frankfurt, Hamburg, Berlin and Eisenstadt.

From 2006 to 2014, Manze was Principal Conductor and Artistic Director of the Helsingborg Symphony Orchestra. He was also Principal Guest Conductor of the Norwegian Radio Symphony Orchestra from 2008 to 2011, and held the title of Associate Guest Conductor of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra for four seasons.

After reading Classics at Cambridge University, Manze studied the violin and rapidly became a leading specialist in the world of historical performance practice. He became Associate Director of the Academy of Ancient Music in 1996, and then Artistic Director of the English Concert from 2003 to 2007. As a violinist, Manze released an astonishing variety of recordings, many of them award-winning.

Manze is a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Music, Visiting Professor at the Oslo Academy, and has contributed to new editions of sonatas and concerti by Bach and Mozart, published by Bärenreiter, Breitkopf and Härtel. He also teaches, writes about, and edits music, as well as broadcasting regularly on radio and television. In November 2011 Andrew Manze received the prestigious ‘Rolf Schock Prize’ in Stockholm.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

Steven Osborne’s musical insight and integrity underpin idiomatic interpretations of diverse repertoire that have won him fans around the world. The extent of his range is demonstrated by his 33 recordings for Hyperion, which have earned numerous awards, and he was made OBE for his services to music in the Queen’s New Year Honours in 2022.

A thoughtful and curious musician, he is often invited to curate festivals, including at Antwerp’s DeSingel, Bath International Music Festival and Antwerp Symphony Orchestra, and has served as Artist-in-Residence at Wigmore Hall. The Observer described him as ‘a player in absolute service to the composer’ and his close reading of composers’ scores has led him to create his own edition of Rachmaninov. He has a lifelong interest in jazz and often improvises in concerts, bringing this spontaneity and freedom to all his interpretations.

Osborne was born in Scotland and studied at St Mary’s Music School in Edinburgh and the Royal Northern College of Music. He is Visiting Professor at the Royal Academy of Music and the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, Patron of the Lammermuir Festival and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 2014.

ASCENDING

WITH ANDREW MANZE AND THE SCO ACADEMY

2-3 May, 7.30pm

Edinburgh | Glasgow

MENDELSSOHN'S ELIJAH

WITH MAXIM EMELYANYCHEV AND THE SCO CHORUS

9-10 May, 7.30pm

Edinburgh | Glasgow

Book Tickets sco.org.uk

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra (SCO) is one of Scotland’s five National Performing Companies and has been a galvanizing force in Scotland’s music scene since its inception in 1974. The SCO believes that access to world-class music is not a luxury but something that everyone should have the opportunity to participate in, helping individuals and communities everywhere to thrive. Funded by the Scottish Government, City of Edinburgh Council and a community of philanthropic supporters, the SCO has an international reputation for exceptional, idiomatic performances: from mainstream classical music to newly commissioned works, each year its wide-ranging programme of work is presented across the length and breadth of Scotland, overseas and increasingly online.

Equally at home on and off the concert stage, each one of the SCO’s highly talented and creative musicians and staff is passionate about transforming and enhancing lives through the power of music. The SCO’s Creative Learning programme engages people of all ages and backgrounds with a diverse range of projects, concerts, participatory workshops and resources. The SCO’s current five-year Residency in Edinburgh’s Craigmillar builds on the area’s extraordinary history of Community Arts, connecting the local community with a national cultural resource.

An exciting new chapter for the SCO began in September 2019 with the arrival of dynamic young conductor Maxim Emelyanychev as the Orchestra’s Principal Conductor. His tenure has recently been extended until 2028. The SCO and Emelyanychev released their first album together (Linn Records) in November 2019 to widespread critical acclaim. Their second recording together, of Mendelssohn symphonies, was released in November 2023.

The SCO also has long-standing associations with many eminent guest conductors and directors including Andrew Manze, Pekka Kuusisto, François Leleux, Nicola Benedetti, Isabelle van Keulen, Anthony Marwood, Richard Egarr, Mark Wigglesworth, Lorenza Borrani and Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen.

The Orchestra’s current Associate Composer is Jay Capperauld. The SCO enjoys close relationships with numerous leading composers and has commissioned around 200 new works, including pieces by the late Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, Sir James MacMillan, Anna Clyne, Sally Beamish, Martin Suckling, Einojuhani Rautavaara, Karin Rehnqvist, Mark-Anthony Turnage and Nico Muhly.

Quilter Cheviot is a proud supporter of the Benedetti Series 2023, in partnership with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. The extension of our partnership continues to show our commitment in supporting culture and the arts in the communities we operate.

For over 250 years, we have been performing for our clients, building and preserving their wealth. Our Discretionary Portfolio Service comes with a dedicated investment manager and local team who aspire to deliver the highest level of personal service, working with you to achieve your goals.

To find out more about investing with us, please visit www.quiltercheviot.com

For 50 years, the SCO has inspired audiences across Scotland and beyond.

From world-class music-making to pioneering creative learning and community work, we are passionate about transforming lives through the power of music and we could not do it without regular donations from our valued supporters.

If you are passionate about music, and want to contribute to the SCO’s continued success, please consider making a monthly or annual donation today. Each and every contribution is crucial, and your support is truly appreciated.

For more information on how you can become a regular donor, please get in touch with Hannah Wilkinson on 0131 478 8364 or hannah.wilkinson@sco.org.uk

sco.org.uk/support-us