THE LARK ASCENDING

WITH ANDREW MANZE AND SCO ACADEMY

2-3 May 2024

THE LARK ASCENDING WITH ANDREW MANZE AND SCO ACADEMY

Thursday 2 May, 7.30pm, The Usher Hall, Edinburgh

Friday 3 May, 7.30pm, City Halls, Glasgow*

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Concerto Grosso ‡

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS The Lark Ascending†

Interval of 20 minutes

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Symphony No 5

Andrew Manze Conductor

Stephanie Gonley Violin†

SCO Academy‡

* This performance will be recorded for the BBC ‘Radio 3 in Concert’ series, due for broadcast on 11 July 2024.

4 Royal Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 5AB +44 (0)131 557 6800 | info@sco.org.uk | sco.org.uk

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra is a charity registered in Scotland No. SC015039. Company registration No. SC075079.

THANK YOU

PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR'S CIRCLE

Our Principal Conductor’s Circle are a special part of our musical family. Their commitment and generosity benefit us all – musicians, audiences and creative learning participants alike.

Annual Fund

James and Patricia Cook

Visiting Artists Fund

Colin and Sue Buchan

Harry and Carol Nimmo

Anne and Matthew Richards

International Touring Fund

Gavin and Kate Gemmell

Creative Learning Fund

Sabine and Brian Thomson

CHAIR SPONSORS

Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen

Donald and Louise MacDonald

Chorus Director Gregory Batsleer

Anne McFarlane

Principal Second Violin

Marcus Barcham Stevens

Jo and Alison Elliot

Second Violin Rachel Smith

J Douglas Home

Principal Viola Max Mandel

Ken Barker and Martha Vail Barker

Viola Brian Schiele

Christine Lessels

Viola Steve King

Sir Ewan and Lady Brown

Principal Cello Philip Higham

The Thomas Family

American Development Fund

Erik Lars Hansen and Vanessa C L Chang

Productions Fund

Bill and Celia Carman

Anny and Bobby White

Anne, Tom and Natalie Usher

Scottish Touring Fund

Eriadne and George Mackintosh

Claire and Anthony Tait

Cello Donald Gillan

Professor Sue Lightman

Cello Eric de Wit

Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund

Principal Double Bass Nikita Naumov

Caroline Hahn and Richard Neville-Towle

Principal Flute André Cebrián

Claire and Mark Urquhart

Principal Oboe Robin Williams

In memory of Hedley G Wright

Principal Clarinet Maximiliano Martín

Stuart and Alison Paul

Principal Bassoon Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Claire and Anthony Tait

Principal Timpani Louise Lewis Goodwin

Geoff and Mary Ball

FUNDING PARTNERS

THANK YOU SCO DONORS

Diamond

Malcolm and Avril Gourlay

John and Jane Griffiths

James and Felicity Ivory

Robin and Catherine Parbrook

Clair and Vincent Ryan

William Samuel

Tom and Natalie Usher

Platinum

David Caldwell in memory of Ann

Judith and David Halkerston

Audrey Hopkins

David and Elizabeth Hudson

Dr and Mrs Peter Jackson

Dr Daniel Lamont

Chris and Gill Masters

Duncan and Una McGhie

Anne-Marie McQueen

James F Muirhead

Patrick and Susan Prenter

Mr and Mrs J Reid

George Ritchie

Martin and Mairi Ritchie

Hilary E Ross

Elaine Ross

George Rubienski

Jill and Brian Sandford

Michael and Elizabeth Sudlow

Robert and Elizabeth Turcan

Alan and Sue Warner

Finlay and Lynn Williamson

Dr Peter Williamson and Ms Margaret Duffy

Ruth Woodburn

William Zachs

Gold

John and Maggie Bolton

Elizabeth Brittin

Kate Calder

Lord Matthew Clarke

Jo and Christine Danbolt

James and Caroline Denison-Pender

Andrew and Kirsty Desson

David and Sheila Ferrier

Chris and Claire Fletcher

Dr J W E Forrester

James Friend

Adam Gaines and Joanna Baker

Margaret Green

Iain Gow

Christopher and Kathleen Haddow

Catherine Johnstone

Gordon Kirk

Robert Mackay and Philip Whitley

Mike and Karen Mair

Anne McAlister and Philip Sawyer

Roy and Svend McEwan-Brown

John and Liz Murphy

Maggie Peatfield

Charles Platt

Alison and Stephen Rawles

Andrew Robinson

Olivia Robinson

Irene Smith

Ian S Swanson

John-Paul and Joanna Temperley

James Wastle and Glenn Craig

Bill Welsh

Catherine Wilson

Neil and Philippa Woodcock

G M Wright

Bruce and Lynda Wyer

Silver

Roy Alexander

Pamela Andrews and Alan Norton

Dr Peter Armit

William Armstrong

Fiona and Neil Ballantyne

Timothy Barnes and Janet Sidaway

The Batsleer Family

Jack Bogle

Jane Borland

Alan Borthwick

Michael and Jane Boyle

Mary Brady

John Brownlie

Laura Buist

Robert Burns

Sheila Colvin

Lorn and Camilla Cowie

Philip Croft and David Lipetz

Lord and Lady Cullen of Whitekirk

Adam and Lesley Cumming

Dr Wilma Dickson

Sylvia Dow

Dr and Mrs Alan Falconer

Sheila Ferguson

Malcolm Fleming

Dr William Irvine Fortescue

Dr David Grant

Andrew Hadden

J Martin Haldane

Ronnie and Ann Hanna

Ruth Hannah

Robin Harding

Roderick Hart

Norman Hazelton

Ron and Evelynne Hill

Philip Holman

Clephane Hume

Tim and Anna Ingold

David and Pamela Jenkins

Susannah Johnston and Jamie Weir

Julie and Julian Keanie

Marty Kehoe

Professor Christopher and Mrs Alison Kelnar

Dr and Mrs Ian Laing

Janey and Barrie Lambie

Graham and Elma Leisk

Geoff Lewis

Dorothy A Lunt

Vincent Macaulay

James McClure in memory of Robert Duncan

Gavin McCrone

Brian Miller

James and Helen Moir

Alistair Montgomerie

Margaret Mortimer and Ken Jobling

Andrew Murchison

Hugh and Gillian Nimmo

David and Tanya Parker

Hilary and Bruce Patrick

John Peutherer in memory of Audrey Peutherer

James S Potter

Alastair Reid

Fiona Reith

Catherine Steel

Ian Szymanski

Takashi and Mikako Taji

Douglas and Sandra Tweddle

C S Weir

We are indebted to everyone acknowledged here who gives philanthropic gifts to the SCO of £300 or greater each year, as well as those who prefer to remain anonymous.

We are also incredibly thankful to the many individuals not listed who are kind enough to support the Orchestra financially on a regular or ad hoc basis. Every single donation makes a difference.

Become a regular donor, from as little as £5 a month, by contacting Hannah Wilkinson on 0131 478 8364 or hannah.wilkinson@sco.org.uk.

“A crack musical team at the top of its game.”

HRH The Former Duke of Rothesay

Patron

Donald MacDonald CBE

Life President

Joanna Baker CBE

Chair

Gavin Reid LVO

Chief Executive

Maxim Emelyanychev

Principal Conductor

Andrew Manze

Principal Guest Conductor

Joseph Swensen

Conductor Emeritus

Gregory Batsleer

Chorus Director

Jay Capperauld

Associate Composer

Our Musicians

YOUR ORCHESTRA

Information correct at the time of going to print

First Violin

Stephanie Gonley

Afonso Fesch

Mark Derudder

Kana Kawashima

Aisling O’Dea

Siún Milne

Amira Bedrush-McDonald

Sarah Bevan Baker

Catherine James

Carole Howat

Second Violin

Marcus Barcham Stevens

Gordon Bragg

Michelle Dierx

Rachel Smith

Niamh Lyons

Stewart Webster

Kristin Deeken

Amy Cardigan

Viola

Max Mandel

Ana Dunne Sequi

Brian Schiele

Steve King

Rebecca Wexler

Kathryn Jourdan

Cello

Philip Higham

Su-a Lee

Donald Gillan

Eric de Wit

Niamh Molloy

Bass

Nikita Naumov

Jamie Kenny

Stewart Wilson

Flute

André Cebrián

Alba Vinti López

Piccolo

Alba Vinti López

Oboe

Robin Williams

Katherine Bryer

Cor Anglais

Katherine Bryer

Clarinet

Kate McDermott

William Stafford

Bassoon

Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Alison Green

Horn

Máté Börszönyi

Jamie Shield

Trumpet

Peter Frank

Shaun Harrold

Trombone

Duncan Wilson

Cillian Ó’Ceallacháin

Alan Adams

Timpani/ Percussion

Louise Lewis Goodwin

Donald Gillan Cello

Donald Gillan Cello

SCO

ACADEMY

Our current SCO Academy programme, delivered in partnership with the City of Edinburgh Council Instrumental Music Service, Glasgow CREATE and St Mary’s Music School has provided a unique opportunity for 39 aspiring young string musicians to rehearse and perform Vaughan Williams’ Concerto Grosso side-by-side with the Orchestra under the guidance of SCO musicians and conductor Andrew Manze himself.

The Concerto Grosso, is uniquely composed for all skill levels with the orchestra divided into three sections based on skill: Concertino (Advanced), Tutti (Intermediate), and Ad Lib (Novice, open strings only).

The SCO Academy ran over two consecutive rehearsal weekends in April. SCO musicians and staff from St Mary’s Music School tutored sectionals and played alongside participants in tutti rehearsals, led by both SCO violinist/conductor Gordon Bragg and Andrew Manze. This has been a unique opportunity for young string musicians of all abilities to develop their musicianship in a fun and inclusive environment, to experience playing as part of a group, and hone essential skills such as listening, teamwork and following a conductor.

Further information at sco.org.uk

This SCO Academy is delivered in partnership with St Mary’s Music School, City of Edinburgh Council Instrumental Music Service and Glasgow CREATE.

Kindly supported by the Penpont Charitable Trust, the Radcliffe Trust, and the Vaughan Williams Foundation. With special thanks to the generous individuals who supported the SCO Christmas Give 2023.

SCO ACADEMY

PLAYERS

VIOLIN 1

Austin Vincent Agarwal

Charlotte Yeaman

Daniel Snee

Dara Omoya

Eilidh Campbell

Emily Win

India Reilly

Joshua Gill

Martha Johnson

Olwen Dimbleby Weber

Theo Arkinstall

Vanessa Zupnik

William Guo

Yeva Hutsul

Zac Nedumpully

VIOLIN 2

Audrey Shea

Constance Qian Bei Cho

Elizabeth McColl

Emma Pantel

Hannah Easdale

Juliette Hood

Michael Park

Niamh Clark

Nikita Bubulchuk

Shreya Saul

ADDITIONAL TUTORS FROM ST MARY’S MUSIC SCHOOL:

Valerie Pearson

Philip Bartai

Ruth Beauchamp

VIOLA

Callum Cook

Charlotte Walker

Emma Zheng

Kathy Ross

Merryn Stephenson

Sandy Reilly

CELLO

Amelie Hartley

Amy Thacker

Dougie Easdale

Freddy Beeston

Laudika Monaghan

Paul Oggier

Trish Strain

BASS

Alexander Kwon

Ava Griffith

Erin Nixon

Sam McInnes

WHAT YOU ARE ABOUT TO HEAR

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS (1872-1958)

Concerto Grosso (1950)

I. Intrada

II. Burlesca Ostinata

III. Sarabande

IV. Scherzo

V. March and Reprise

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS (1872-1958)

The Lark Ascending (1914, rev. 1920)

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS (1872-1958)

Symphony No 5 in D major (1938-43)

I. Preludio

II. Scherzo

III. Romanza

IV. Passacaglia

Musical visionary, even mystic; champion of Britain’s age-old musical heritage, and of England’s pastoral beauties. It’s perhaps no surprise that the music of Ralph Vaughan Williams is among our country’s most popular – indeed, one of tonight’s pieces regularly tops charts for the best-loved classical piece ever written. But for all its comforting reassurance, Vaughan Williams was also a deeply progressive, questing composer, one profoundly aware of the context and purpose of his music, as well as who was listening to it and who was playing it.

In the case of this evening’s first piece, those players were the young musicians of the Rural Schools Music Association, performing in London’s Royal Albert Hall in November 1950 under conductor Adrian Boult. Vaughan Williams had been approached by the Association earlier that year with the suggestion that he might write something for an orchestra of string players of decidedly mixed abilities – some would be accomplished young musicians about to head off to music college, but others would almost be complete beginners, only able to play on open strings.

Vaughan Williams was intrigued, and inspired – and he quickly launched into work on what became his Concerto Grosso. And he developed a novel solution to the question of those mixed abilities. He already had form in subdividing his musical ensembles into different subgroups with contrasting roles – just think of the quartet, chamber group and larger ensemble that conjure the threedimensional sonic perspectives of his luminous Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis , which he’d written back in 1910.

For his Concerto Grosso, Vaughan Williams came up with something similar. A ‘concertino’ group of advanced players would get the most challenging material; a ‘tutti’ group of intermediate musicians would play slightly more straightforward parts; and an ‘ad lib’ group for beginners would receive the simplest music of all, with the option of playing even just open strings.

The implications of this way of thinking are, when you think about it, quite profound. Vaughan Williams’ Concerto Grosso is in no way music for children –at least not in the manner of Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf or Britten’s Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra . Instead, it’s music for children themselves to play – and complex, sophisticated music aimed at knowledgeable listeners, but cunningly conceived so that those with little experience can take part in the performance. Instead of challenging

It’s music for children themselves to play – and complex, sophisticated music aimed at knowledgeable listeners, but cunningly conceived so that those with little experience can take part in the performance.

young players to rise to the difficulties of my musical language, Vaughan Williams seems to be saying, I’ll challenge myself to express my musical ideas in a way that matches their capabilities.

Like the 1950 Royal Albert Hall premiere – which reportedly involved getting on for 400 young players – tonight’s performance brings together players of many different levels of experience. Joining the SCO’s professional musicians are players from the SCO Academy, a project delivered by the Orchestra in partnership with City of Edinburgh Council Instrumental Music Service, Glasgow CREATE and students and staff from St Mary’s Music School. The SCO Academy, which has been running since 2019, provides opportunities for young musicians to rehearse and perform alongside professional musicians, free of charge. You’ll hear the results of those rehearsals in tonight’s performance.

Ralph Vaughan WilliamsVaughan Williams’ title is particularly apt, and in his music, he draws substantially on the Baroque concerto grosso form, with its contrasts between a more showy ‘concertino’ group of soloists and an accompanying ‘ripieno’ ensemble (though, in fairness, those roles were often largely merged). Swaggering, swirling harmonies launch the grand opening ‘Intrada’, richly scored across all three orchestral subgroups, and the movement ends with a sense of luminosity similar to that of the Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis . The angular main theme of Vaughan Williams’ second movement, ‘Burlesca ostinata’, is itself based around the instruments’ open strings, allowing less experienced players their time in the spotlight, though quieter, most ghostly music emerges to close the movement quietly.

After the slow, sombre waltz of the third-movement ‘Sarabande’, Vaughan Williams set off his lively ‘Scherzo’ with a spiky theme, contrasting it with a quieter section with a rocking violin melody. A gentle violin march kicks off his concluding ‘March and Reprise’, but just as it appears to be gathering steam for a grand climax, Vaughan Williams moves us back into the pomp and grandiosity of the opening ‘Intrada’, ending the piece as it began.

From the multi-level, multi-layered Concerto Grosso, we hop back in time a few decades for what’s surely the composer’s best-loved and best-known piece of all. Indeed, the nostalgic and very English rural idyll of Vaughan Williams’ The Lark Ascending regularly tops polls as the UK’s best-loved piece of classical music – but with its quiet introspection, and the complete absence of a ‘big tune’

to stir the spirits, it’s an unusual work to receive such adulation.

It’s surprising, too, that such a calm, serene piece can have been created during a time of war. Vaughan Williams completed The Lark Ascending in its original version for violin and piano in 1914, then set it aside for the duration of the First World War, during which time he served as an ambulance driver in France and Greece. Upon his return to Britain, he finished the work’s orchestration, and The Lark Ascending was premiered by its dedicatee Marie Hall in June 1921 at London’s Queen’s Hall.

The composer had been inspired by the 1881 poem by George Meredith of the same name, and included these lines from it in his score:

He rises and begins to round, He drops the silver chain of sound, Of many links without a break, In chirrup, whistle, slur and shake. For singing till his heaven fills, ’Tis love of earth that he instils, And ever winging up and up, Our valley is his golden cup And he the wine which overflows to lift us with him as he goes. Till lost on his aerial rings In light, and then the fancy sings.

Meredith’s imagery, and the natural wonders of England that he evokes, are a world away from the brutal reality of conflict into which Vaughan Williams found himself thrown. We can only wonder at the ways in which the bloody destruction of the battlefield that the composer witnessed might have set his nostalgic idyll into stark relief – or, indeed,

served to re-emphasise its vision and values in the composer’s mind.

As his violin soloist takes on the role of the eponymous lark, easing us gently into the piece’s subtly perfumed harmonies, and soaring ever higher at the work’s conclusion to sing its bewitching song, what Vaughan Williams offers us is a space for reflection. There’s a gentle sense of spirituality, too, even a feeling of mysticism, and an underlying sense of sadness – perhaps for the rural world that Vaughan Williams loved so much, and which even in 1914 he could see disappearing.

From one catastrophic 20th-century conflict to another. Like our opening Concerto Grosso, Vaughan Williams’ Fifth Symphony received its premiere in London’s Royal Albert Hall. But the Symphony’s first performance took place

Still today, it’s a piece with deep personal associations for many listeners, one that brings a sense of comfort and solace, even hope, during difficult times.

seven years earlier, on 24 June 1943, at the height of the Second World War.

Eight years previously, certain listeners had been shocked by the same composer’s violent, thorny Fourth Symphony, completed in 1935 as Europe seemed to be heading inexorably ever closer to cataclysmic conflict. ‘I’m not at all sure that I like it myself now,’ the composer later famously admitted. ‘All I know is that it's what I wanted to do at the time.’

For the Symphony that he wrote and unveiled during that conflict itself, however, Vaughan Williams shocked some listeners again. This time it wasn’t because of violence, but because of his wartime Fifth Symphony’s sense of calm, reflection and deep spirituality. Even today, it’s a piece with deep personal associations for many listeners, one that brings a sense

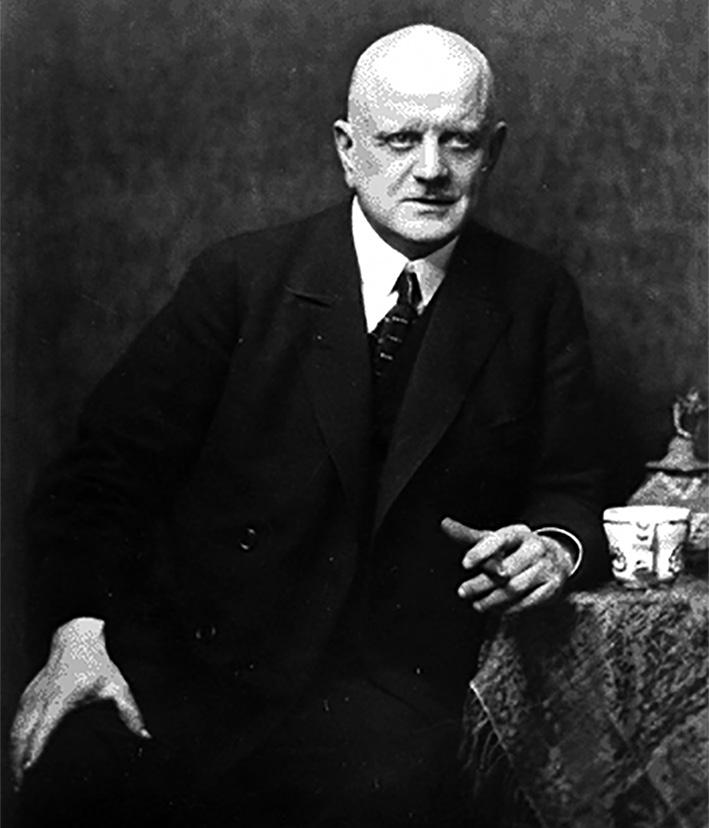

Vaughan Williams at about the time of the composition of The Lark Ascendingof comfort and solace, even hope, during difficult times.

The Symphony is indeed one of Vaughan Williams’ most deeply loved pieces, right up there in many ways with The Lark Ascending. Fellow composer Aaron Copland rather acidly commented on certain similarities with Vaughan Williams’ earlier pastoral works, pronouncing: ‘Listening to the Fifth Symphony of Ralph Vaughan Williams is like staring at a cow for 45 minutes.’ But surely that’s missing the point. If anything, the Fifth Symphony has more in common with the hushed spirituality of the Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis. And in many ways, it’s just as intricate, sophisticated and complex a work as its uncompromising symphonic predecessor, even if its language is one of tenderness and contemplation.

Vaughan Williams began sketches for the Fifth Symphony in 1936, but worked in earnest on it between 1938 and 1943. And in it, he explained, he also reworked material from his (at that time unfinished) opera The Pilgrim’s Progress , which wouldn’t be seen on stage until its Covent Garden premiere in 1951.

But as well as being a transcendental response to war, Vaughan Williams’ Fifth is also possibly a response to love. The composer had married Adeline Fisher in 1897, and devoted more and more time to her care as she grew increasingly debilitated by arthritis, until her death in 1951. In 1938, however, he met the poet Ursula Wood, an encounter that both remembered as love at first sight – despite the composer being almost 40 years her senior, and despite both of them being married. They went on

to maintain a secret affair for almost a decade, finally marrying in 1953. While she lived, however, Vaughan Williams’ commitment to his first wife Adeline remained undiminished. It’s certainly at least possible that Vaughan Williams’ feeling of new love – however difficult the three individuals’ circumstances – may have injected a fresh sense of hope and optimism into his music.

To war, love and opera, we can add yet another element into the Symphony’s genesis: this time, a fellow composer. On the opening page of the score, Vaughan Williams wrote: ‘Dedicated without permission to Jean Sibelius’. Or at least that was his final version. Earlier, his dedication had read: ‘Dedicated without permission, with the sincerest flattery, to Jean Sibelius, whose great example is worthy of imitation.’ The lack of permission is perhaps simply explained by tricky wartime communications, and the difficulty of relaying messages between Britain and Finland. More importantly, Vaughan Williams held the music of Sibelius in high esteem, and it’s even been suggested that he consciously used the Finnish composer’s thorny Fourth Symphony as a template for his own Fifth – exactly the same notes open both pieces, for example. It might feel, however, like Sibelius’ Sixth Symphony – written in 1923, two decades before the premiere of Vaughan Williams’ Fifth – is closer in spirit to the later work. It’s the Symphony that Sibelius famously referred to in a memorable observation: ‘whereas most other modern composers are engaged in manufacturing cocktails of every hue and description, I offer the public pure cold water.’ That sounds like an apt description of certain sections of Vaughan Williams’ Fifth, too.

A lot of the Symphony’s feeling of purity, consolation and contemplation is conveyed through its musical construction. And it’s with a musical conundrum that Vaughan Williams launches his opening ‘Preludio’. A gently rocking melodic idea from the horns offers a clear sense of key (D major), but the drone in the lower strings is on an alien note (C). Which key are we actually in? It’s the question – left unresolved at the end of the opening movement – that drives the Symphony forward, and which is only answered in the concluding moments of the final movement.

After that initial two-key conflict, violins add an elegant rising and falling melodic idea that seems to form a bridge between both, later moving on to a more demonstrative melody, as though demanding to be heard. A faster-moving central section pits ominous, lamenting figures in the woodwind against sinister running ideas in

Earlier, his dedication had read: ‘Dedicated without permission, with the sincerest flattery, to Jean Sibelius, whose great example is worthy of imitation.’

the strings, but we eventually return to the opening music – ending with the same clash of two unrelated ideas that we heard at the beginning.

Swirling strands of sound dart back and forth across the orchestra in the second movement ‘Scherzo’, as though we’re glimpsing half-seen characters in the murk, though a more folk-like, dancing main melody quickly emerges from flutes and clarinets. Vaughan Williams’ first contrasting section plays rhythmic games with unsettling syncopations, and his second develops into an outspoken march. The swirling opening music barely has a chance to make a return before the movement vanishes in a puff of smoke.

If the Symphony’s first and last movements mark the work’s journey from conflict to resolution, the third movement ‘Romanza’ stands as the piece’s emotional heart.

Jean SibeliusThe music simply moves into a radiant D major, as if that sense of home had been waiting for us there all along. Vaughan Williams’s quiet, slow-moving conclusion – as string lines soar ever higher against a long-held note in the double basses – can only be described as transcendent.

Quietly radiant string harmonies introduce a long, reflective melody from the cor anglais, ultimately leading to a rising, yearning melody in the strings that forms the movement’s most overtly emotional material. Louder, more urgent materal in the centre of the movement develops into the Symphony’s only moments of anguish, before the yearning string melody returns, and a solo violin, Lark Ascending-style, leads the movement to a contemplative close.

For his final movement, Vaughan Williams offers not a victorious finale, but a thoughtful ‘Passacaglia’ built on top of a repeating bassline, heard in the cellos right at the start of the movement. And though the composer treats that bassline with considerable freedom as it returns again and again, there’s an undeniable sense of comfort and security provided by its presence. There’s a feeling, too, of light, air and gentle movement after the emotional

intensity of the preceding movement, and of quiet celebration as the music moves through many moods and textures.

But there are bigger questions to answer. A surging timpani roll throws us back into the conflicted, two-key music that opened the Symphony, now forcefully delivered by the full orchestra (and artfully combined with the passacaglia bassline). Ultimately, it’s the calm, beatific harmonies of the horns that win the day. The first movement’s conflict is ultimately resolved, but without any grand battles, struggles, triumphs of victories. The music simply moves into a radiant D major, as if that sense of home had been waiting for us there all along. Vaughan Williams’ quiet, slow-moving conclusion – as string lines soar ever higher against a long-held note in the double basses – can only be described as transcendent.

© David Kettle

Conductor ANDREW

MANZE

Andrew Manze is widely celebrated as one of the most stimulating and inspirational conductors of his generation. His extensive and scholarly knowledge of the repertoire, together with his boundless energy and warmth, mark him out. He held the position of Chief Conductor of the NDR Radiophilharmonie in Hannover from 2014 until 2023. Since 2018, he has been Principal Guest Conductor of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra; he has just been announced as Principal Guest Conductor of the SCO from the 24/5 Season.

In great demand as a guest conductor across the globe, Manze has long-standing relationships with many leading orchestras, and in the 23/24 season will return to the Royal Concertgebouworkest, the Munich Philharmonic, Rotterdam Philharmonic, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Bamberg Symphoniker, Oslo Philharmonic, Finnish Radio, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Mozarteum Orchester Salzburg, RSB Berlin, and the Dresden Philharmonic among others, and will lead the Chamber Orchestra of Europe in their tour of Frankfurt, Hamburg, Berlin and Eisenstadt.

From 2006 to 2014, Manze was Principal Conductor and Artistic Director of the Helsingborg Symphony Orchestra. He was also Principal Guest Conductor of the Norwegian Radio Symphony Orchestra from 2008 to 2011, and held the title of Associate Guest Conductor of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra for four seasons.

After reading Classics at Cambridge University, Manze studied the violin and rapidly became a leading specialist in the world of historical performance practice. He became Associate Director of the Academy of Ancient Music in 1996, and then Artistic Director of the English Concert from 2003 to 2007. As a violinist, Manze released an astonishing variety of recordings, many of them awardwinning.

Manze is a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Music, Visiting Professor at the Oslo Academy, and has contributed to new editions of sonatas and concerti by Bach and Mozart, published by Bärenreiter, Breitkopf and Härtel. He also teaches, writes about, and edits music, as well as broadcasting regularly on radio and television. In November 2011 Andrew Manze received the prestigious ‘Rolf Schock Prize’ in Stockholm. For full biography please

STEPHANIE GONLEY

Stephanie has a wide-ranging career as concerto soloist, soloist/director of chamber orchestras, recitalist and a chamber musician. She has appeared as soloist with many of UK’s foremost orchestras, including the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Philharmonia and BBC Symphony Orchestra.

Stephanie is leader of the English Chamber Orchestra and the Scottish Chamber Orchestra and has performed as Director/Soloist with both. Stephanie has also appeared as Director/ Soloist with the Australian Chamber Orchestra, the Vancouver Symphony, and the Oriol Ensemble Berlin to name but a few.

She has enjoyed overseas concerto performances with everyone from the Chamber Orchestra of Europe and Hannover Radio Symphony, to Hong Kong Philharmonic and the Norwegian Radio Symphony Orchestra, while her recordings include Dvorák Romance with the ECO and Sir Charles Mackerras for EMI, and the Sibelius Violin Concerto for BMG/ Conifer.

Stephanie is currently Professor of Violin at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. She was a winner of the prestigious Shell-LSO National Scholarship.

SCOTTISH CHAMBER ORCHESTRA

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra (SCO) is one of Scotland’s five National Performing Companies and has been a galvanizing force in Scotland’s music scene since its inception in 1974. The SCO believes that access to world-class music is not a luxury but something that everyone should have the opportunity to participate in, helping individuals and communities everywhere to thrive. Funded by the Scottish Government, City of Edinburgh Council and a community of philanthropic supporters, the SCO has an international reputation for exceptional, idiomatic performances: from mainstream classical music to newly commissioned works, each year its wide-ranging programme of work is presented across the length and breadth of Scotland, overseas and increasingly online.

Equally at home on and off the concert stage, each one of the SCO’s highly talented and creative musicians and staff is passionate about transforming and enhancing lives through the power of music. The SCO’s Creative Learning programme engages people of all ages and backgrounds with a diverse range of projects, concerts, participatory workshops and resources. The SCO’s current five-year Residency in Edinburgh’s Craigmillar builds on the area’s extraordinary history of Community Arts, connecting the local community with a national cultural resource.

An exciting new chapter for the SCO began in September 2019 with the arrival of dynamic young conductor Maxim Emelyanychev as the Orchestra’s Principal Conductor. His tenure has recently been extended until 2028. The SCO and Emelyanychev released their first album together (Linn Records) in November 2019 to widespread critical acclaim. Their second recording together, of Mendelssohn symphonies, was released in November 2023.

The SCO also has long-standing associations with many eminent guest conductors and directors including Andrew Manze, Pekka Kuusisto, François Leleux, Nicola Benedetti, Isabelle van Keulen, Anthony Marwood, Richard Egarr, Mark Wigglesworth, Lorenza Borrani and Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen.

The Orchestra’s current Associate Composer is Jay Capperauld. The SCO enjoys close relationships with numerous leading composers and has commissioned around 200 new works, including pieces by the late Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, Sir James MacMillan, Anna Clyne, Sally Beamish, Martin Suckling, Einojuhani Rautavaara, Karin Rehnqvist, Mark-Anthony Turnage and Nico Muhly.

Host Jay Capperauld

DJ Dolphin Boy

Creators Daniel Abrahams, naafi and Emily Scott-Moncrieff

UN:TITLED

Music by Capperauld, Connesson, Soundbox Live and Adams

Saturday 15 June 7.30pm Assembly Roxy, Edinburgh Sunday 16 June 7.30pm St Luke’s, Glasgow

WORKING IN HARMONY

Quilter Cheviot is a proud supporter of the Benedetti Series 2023, in partnership with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. The extension of our partnership continues to show our commitment in supporting culture and the arts in the communities we operate.

BE PART OF OUR FUTURE

For 50 years, the SCO has inspired audiences across Scotland and beyond.

From world-class music-making to pioneering creative learning and community work, we are passionate about transforming lives through the power of music and we could not do it without regular donations from our valued supporters.

If you are passionate about music, and want to contribute to the SCO’s continued success, please consider making a monthly or annual donation today. Each and every contribution is crucial, and your support is truly appreciated.

For more information on how you can become a regular donor, please get in touch with Hannah Wilkinson on 0131 478 8364 or hannah.wilkinson@sco.org.uk