6 minute read

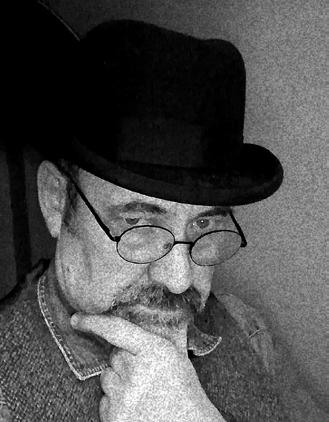

Strange tales from Scotland’s thin places with...Thomas MacCalman Morton

Samuel Pepys's Shetland war crime

South House in Heylor, Ronas Voe is one of the oldest houses in Shetland still habitable, and it is named on the 1641 Henricius Hondius map of the islands.

Advertisement

In the week before the compulsory lockdown, I self isolated there in what is now, for the most part, a holiday cottage, as I was betraying some worrying symptoms, and it was important to not infect my wife, who is a working doctor. Fortunately they came to nothing, but it was a chance to reacquaint myself with a house and a location which is very special. And very much one of those strange and thin places, with many tales intertwining with its history.

Ronas Voe

Ronas Voe is the longest and steepest-sided sea loch, or voe, in Shetland, and the nearest thing to a Fjord the islands possess. It is over shadowed by the highest peak in Shetland, Ronas Hill, the ‘Ro’ referring to its red granite.

The voe itself was of course an important anchorage, both for the herring fleets and indeed for whalers bringing their catches to the busy stations at the end of the Voe. It is a place where you can feel the history, I always think, where once it was possible to walk right across the voe to Abram’s Ward from the beach called the Blade and never get your feet wet, such was the clustering of fishing boats.

The old shop, now roofless, was a thriving centre of trade and there was even a trackway. Until recently bits of the old bogies were being used to hold down boats by the shore.

Photo by Ronnie Robertson CC BY-SA 2.0

But it’s also a place of tragedy, battle and possibly mass murder. And one of the most one-sided and ignominious victories the Royal Navy ever fought.

The Wapen Van Rotterdam, captained by Jacob Martins Cloet, was an 1100-ton Dutch East Indiaman armed with 60 or 70 cannon and with a company of soldiers aboard. In December 1673 she set sail from the Frisian Islands, bound for the Dutch East Indies.

There was a war on. The Third Anglo-Dutch war meant the Royal Navy had a stranglehold on the Wapen Van Rotterdam’s obvious route through the English Channel, so she headed nortaboot. Bad weather took its toll, she was dismasted, lost her rudder and, with southerly winds prevailing and using who knows what variety of jury rig, she was steered into the shelter of Ronas Voe for repairs.

And couldn’t get out again. A lack of usable wood and the continuing southerlies meant she was stuck through the winter, trading gin and tobacco with the Heylor folk, who were more than likely very familiar with Dutch seafarers and fishermen. They probably quite enjoyed the fresh Genever and other goods the just-out-of-port East Indiaman had aboard. It’s possible that the ordinary people of Northmavine had little notion they were technically at war with the stranded sailors, thanks to the Union of the Crowns under James VI of Scotland and I of England in 1603.

Samuel Pepys

But someone did, probably a local minister or laird. The Admiralty in London was tipped off, and in February 1674 a flotilla of four ships was sent north to capture the Dutch vessel. HMS Cambridge, captained by Arthur Herbert (later the Earl of Torrington); HMS Newcastle, captained by a man with very unlikely name, John Wetwang (later Sir John Wetwang); HMS Crown,captained by Richard Carter; and Dove, captained by Abraham Hyatt. Dove was wrecked on the way north.

We have the legendary diarist Samuel Pepys, Chief Secretary to the Admiralty for the detail of what followed, and some of the nefarious, greedy skulduggery, deliberate ignorance or confusion which led to massive bloodshed. Pepys was keen that everything be done swiftly, and for a very good reason. A peace treaty had been signed between Holland and Great Britain. Unless the Navy moved fast, they would have no excuse to take that Ronas Voe prize. Pepys stated the orders were "at the desire of the Royal Highness (Charles II)", pointing out on 21 February that the Treaty of Westminster concluding the war was expected to be published within eight days, and any subsequent hostilities were to last no longer than 12 days. The Treaty of Westminster had in fact been signed two days prior to this letter being sent, and was ratified in England the day previously.

Action during the war with Holland depicted by The Burning of the ‘Royal James’ at the Battle of Solebay 1672

The three RN ships remaining - Cambridge, Newcastle and Crown, finally engaged with the Wapen Van Rotterdam on 14 March. One day after Pepys's original 20 day deadline and 23 days after the signing of the Treaty of Westminster. The war was over. But not the shooting.

There are no details of the battle, though it must have been incredibly one sided. The three Royal Navy vessels had a rudderless, dismasted ship to deal with in a very confined area, and a Dutch crew and soldiers almost certainly unsuspecting and unready for conflict. Nevertheless, Captain Cloet decided to fight it out. And he may even have fired the first shot. It was hopeless. The tragedy is that of the 400 men aboard the Wapen Van Rotterdam, only 100, the captain among them, were transferred to the Crown as prisoners.

Bar shot relic of the Battle of Ronas Voe

Photo Roy Mullay CC BY 4.0

Some may have been taken aboard other British ships, but it is horrifyingly possible that the ‘Hollander’s Grave’ at Heylor marks the burial place of 300 Dutch soldiers and sailors. It is also possible that some had deserted and that even to this day, their bloodlines run through Shetlanders.

As for the Wapen Van Rotterdam, she was towed to Harwich and then the Thames, the crew were sent home and the ship’s contents auctioned (full details were kept and if you search online, you can find that 21 puncheons of vinegar went for £84, equivalent to £12,190 today). That she was fit to be towed makes one wonder how much damage was done to her during the battle, and if so many Dutchmen were killed, how that happened without sinking the East Indiaman. At any rate, the Royal Navy captains were well rewarded in prize money, and the Wapen Van Rotterdam herself became HMS Arms of Rotterdam, ending up as an unarmed hulk. The only mention made of the uncertain legality of the battle came from Samuel Pepys, who told Captain Herbert that the House of Lords had commented: "Long may the civility which you mention of the Dutch to his Majesty's ships continue." No more fighting, lads. Or if there is, make sure the war is still on.

The site of the “Hollanders Grave” is marked today with a small stone and plaque, a piece along the shore from the crab factory towards the Blade. It’s possibly the site of a war crime. When you walk down there in the simmer dim, the endless light of the Shetland summer, it has a very poignant atmosphere.

The Chaa-ans and Hollanders Grave

Photo John Dally CC BY-SA 2.0

But when the sea fog rolls in like a living creature, the wind drops and the air assumes an odd deadness, a lack of echo, you can imagine shapes moving there, dozens, hundreds of them. And amid the murmur of sea on shingle, sheep bleating and seabirds ticking and squawking, you may think you hear conversations.

Dutch is a difficult language, though, if you’re not a native speaker…