8 minute read

Polished Off - Kiwi Shoe Polish Stops Selling in Britain

by John Greeves

So where have all these once familiar products and brands gone? You probably have your own childhood list of bygone favourites including penny sweets like: sweet banana, chocolate mice, pink shrimps and chewy black jacks. Even the chopper bike, Subbuteo table football and the Pogo ball, that once promised to ‘jump you out of the 50s into the 80s,’ have all sadly had their day. If this isn’t your era, then think about the rapid pace of obsolescence in the last decade or so. Gone are incandescent light bulbs, Kodak film, TV consoles, floppy discs, rotary telephones, fax machines, Internet Explorer, yellow pages directories, internal CD and DVD drives with a new computer...even the printed editions of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, have vanished, shrouded in an ephemeral mist of yesterday’s news. You just have to check out the declining high street, to see wellknown brands and products, we thought would last for ever, now declared extinct.

Advertisement

Now I learn ‘Kiwi Shoe Polish’ is the next to leave our sceptred isle. It seems, Britons are not polishing their shoes and boots frequently enough and the market leader has decided it’s not worth selling Kiwi shoe polish in the UK any more. A spokesperson for SC Johnson explained why Kiwi Shoe Polish had decided to leave Britain. “The Shoe Polish category has shown a steady and long-term decline. There are several reasons for this change in demand, including a rise in wearing of casual shoes, which do not require formal polishing, and an overall decrease in consumers polishing their shoes. SC Johnson continues to maintain an active presence for the iconic Kiwi® brand in markets where formal shoe care remains relevant.”

Sad to think that the act of polishing your shoes, once had the same cachet as learning to swim, riding a bicycle or telling the time when you were younger. Polishing your shoes became a regular ritual every Sunday night in readiness for school the next day. There was a set protocol. First the laying down of a broad sheet newspaper, then the assemblage of various hard and soft bristle brushes, a rite of passage with an undisputed order: shoes must be clean and dry before starting; polish was to be applied with a clothe or a hard bristle small brush and allowed to dry. Only then could buffing begin with a larger soft bristle brush in rapid movement until a mirror glean appeared. You weren’t finished yet, before another light coat of polish was applied and the shoes sprinkled with water, before buffing them up again to a military shine.

Kiwi shoe polish seems to have been with us, our parents and grandparents all their lives. Its origins began in 1906, when a Scottish ex-pat called William Ramsay (eldest son of John Ramsay), launched his shoe polish in Australia. William had arrived in Melbourne, with his parents and his brothers John and Hugh. The family soon expanded with three sisters and two more brothers born in Melbourne. William initially joined his father in John Ramsay & Son, a prosperous real estate business until he ventured out on his own. In New Zealand he met and married his wife Annie Elizabeth Meek in 1901, before he returned to Melbourne to establish his own enterprise where he formed a partnership with Hamilton McKellan, manufacturing a range of products including disinfectant powder, stove polish and boot cream. The first KIWI factory was at 62 Bouverie Street in Carlton, Melbourne, Australia.

‘Kiwi’ polish came later and was named after his New Zealand wife. The polish was not the first boot polish on the market, but what made it different was its formula to preserve and restore the colour of leather and make it water resistant. By the end of the first year William had sold 86 gross and within ten years KIWI had sold 30 million tins of polish. The range increased and included: Dark Tan, Light Tan, Brown, Ox Blood, Black and a patent leather polish.

After the war sales of the Kiwi shoe polish continued to grow with distribution in fifty countries. Times change, and the company survived the Big Crash of 1929, the second World War and later the process of modernisation. During the second World War, one American correspondent, Walter Graeber even described the Tobruk trenches in 1942, where “Old tins of Britishmade Kiwi polish lay side by side with empty bottles of Chianti,” an affirmation that Kiwi Shoe Polish had become a global product. Indeed, the breaching of the American market occurred a few years after the war when a new factory was opened in Philadelphia.

Modernisation, expansion, new machinery, quality control and new products became the buzz words for the company during the fifties and further new plants opened in Britain, India, France, Canada, South Africa, Spain and Pakistan. By 1967, the company had grown so big that all its diverse interest needed to be brought under an umbrella company so Kiwi International, was born. Other changes occurred, and in 1982, a merger took place between two well established Australian companies, Nicholas International Ltd and the Kiwi Polish Company Proprietary Ltd that now formed Nicolas Kiwi.

Sales rose dramatically with a growing acceptance for this product which offered quality and performance, along with a wider application for saddles and other leather goods.

By 1908, Ramsay began to export to New Zealand and Europe. In 1912, the Ramsay family established a sales office in Southampton, England with a staff of three. Leather shoes and boots were becoming more available to the public, so the demand for a quality and dependable polish increased. Unfortunately, William died aged 47 in 1914, never realising the true global impact of the product would make in the future. The company would remain a family run business for several decades.

During the first world war, the polish became increasingly popular with soldiers in the British and US armies. Trench warfare had brought with it a dreadful condition called ‘trench foot.’ One way to avoid this was by having dry feet and ensuring your boots were Kiwi water resistant. A single order from the British Army totalled 10,000 gross. (Roughly 1.44 million tins).

Dealings didn’t stop there and in 1984, Kiwi was bought by Sara Lee Corporation, before being sold in 2011 to SC Johnson, the present owners who now want to focus their activities on other priorities. Kiwi Polish will no longer be sold in the UK, the firm will instead sell products in countries where formal shoe care “remains relevant.” It is still bought in more than 120 countries and accounts for more than half of the shoe polish sold globally.

Kiwi shoe polish has been a part of Romi Topi’s and his family life. He’s sad the shoe polish, so familiar to various generations of his family has finally gone from Britain, but like all good businesses he acknowledges change.

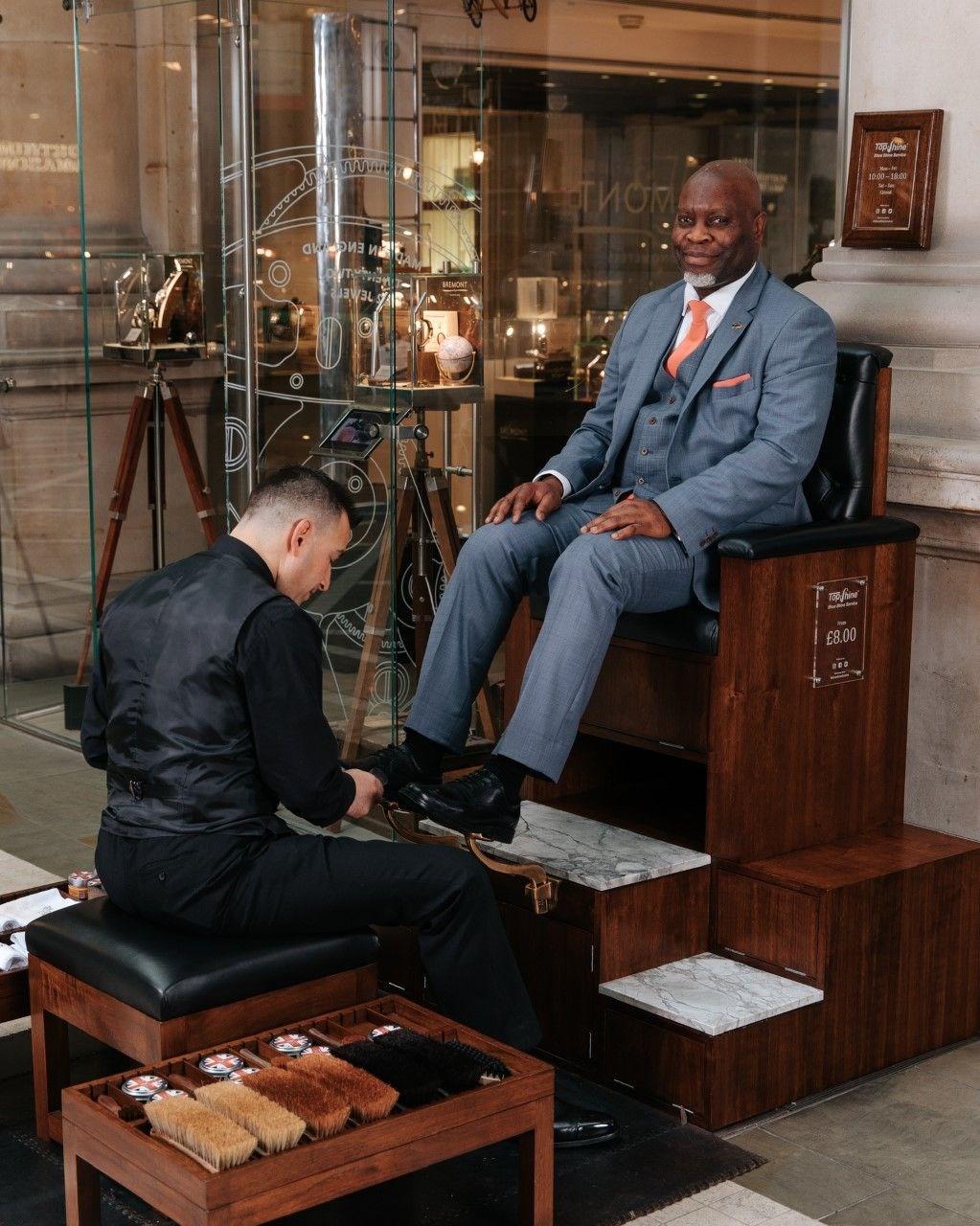

Romi Topi, runs Top Shine Shoe Shine services which has provided a services for the last 22 years. He was taught to polish shoes by his father. The services are based in two prestigious locations in London’s Burlington Arcade and The Royal Exchange. Romi tells me “When we talk about shoe polish we automatically think ‘Kiwi Shoe Polish’. It was always there on the shoe cabinet and it’s been part of our lives.” Romi puts the falling sale of Kiwi polish down to a number of factors including the increase of British shoe makers selling shoe care products, the change of life style that has occurred during Covid and compares the City more to a university campus, than a formal working environment. He and his colleges have had to adapt their services to new footwear trends in addition to polishing leather shoes to catering for the rise in casual wear. Some people are paying £3,000 for Nikes, so it makes sense to know how to clean trainers. His service not only polishes shoes (£8), cleans Suede (£12) but now offers a trainer service (£15) as well as selling a range of his own “Top Shine” shoe products.

Of course, change has to happen, but perhaps what is most disconcerting is the rate at which quality brands and products are disappearing from our shores. You have to wonder what’s next when it comes to the future culling of much loved products. Formality it seems has been cast aside, with the once famous city gent, formerly ‘suited and booted.’ He’s now replaced by a casually dressed office worker with shoulder bag and of course those ubiquitous trainers (who wouldn’t be out of place at Glastonbury) and whose only interface these days, appears to be with an office computer.

John Greeves originally hails from Lincolnshire. He believes in the power of poetry and writing to change people’s lives and the need for language to move and connect people to the modern world. Since retiring from Cardiff University, Greeves works as a freelance journalist who's interested in an eclectic range of topics .

by Maressa Mortimer

April seems such a sweet, Spring-like month, although it’s quite capable of giving snow as well. To me, the April just before we adopted our children, was a stormy one, that passed in a blur. We had been running a language school from our house for a few years, so whilst getting ready to bring three young children home, our house was filled with teenagers most weeks.

Having had to go through a stack of paperwork in the previous year, it seemed surreal that we had suddenly come to the end of the journey, and were actually going to be parents. Nearer the end of the month, we started using host families for the teenagers, allowing us to finalise the rooms, adding the little beds and soft toys that featured in the DVD we made for them.

Walking around Ikea, we wondered how many things we could get into our car. It was tempting to buy every toy we could afford, but we stuck to cute kids' plates and cutlery. Maybe the odd extra. Or maybe a few odd extras. Those kids' curtains were very cute and we simply needed spare bedding, right?

We prepared the house and garden, installed stair gates, set up a cot, and filmed ourselves going around the house, showing our childrento-be where they would live. It might have felt awkward and cheesy, but it did serve its purpose. For the two younger ones, we made talking picture books, all the while teaching teenagers to speak English and playing language games around the area.

In April of that year, we met the foster carers looking after our children, which felt odd. We talked to them, and after the meeting, they went home, to what would become our children. After each meeting, we travelled home again, to cook ginormous meals for hungry sixteen-year-olds. After the meal, when the teens had gone to bed, we would look at pictures of our three little ones.

The months passed so quickly, although it didn’t feel like it at the time. Soon, we were on our way to the sweet cottage social services had rented for us, and we would meet our children for the very first time. I had been teaching most of the day, and my adrenalin made me feel shaky for most of the long journey. How surreal, to meet your children, who you have only seen in pictures, but we had such strong feelings for them already.

So, each April, I feel the chaos won’t be as wild as that one April, ten years ago.

Maressa Mortimer is Dutch but lives in the beautiful Cotswolds, England with her husband and four (adopted) children. Maressa is a homeschool mum as well as a pastor’s wife, so her writing has to be done in the evening when peace and quiet descend on the house once more. All of Maressa’s books are available from her website, www.vicarioushome.com, Amazon or local bookshops.