MODERN MASTERS XVIII

MODERN MASTERS XVIII

Paintings, Prints & Tapestries

January & February 2025

Introduction | Origins p1 VINTAGE | The Edinburgh School p2 Robin Philipson | The Magician of the Brush p7 Modern Masters | Paintings p22

VINTAGE | A Forgotten Pioneer of Abstraction p128 Modern Masters | Prints p138 A History of Printmaking at The Scottish Gallery p148

Origins

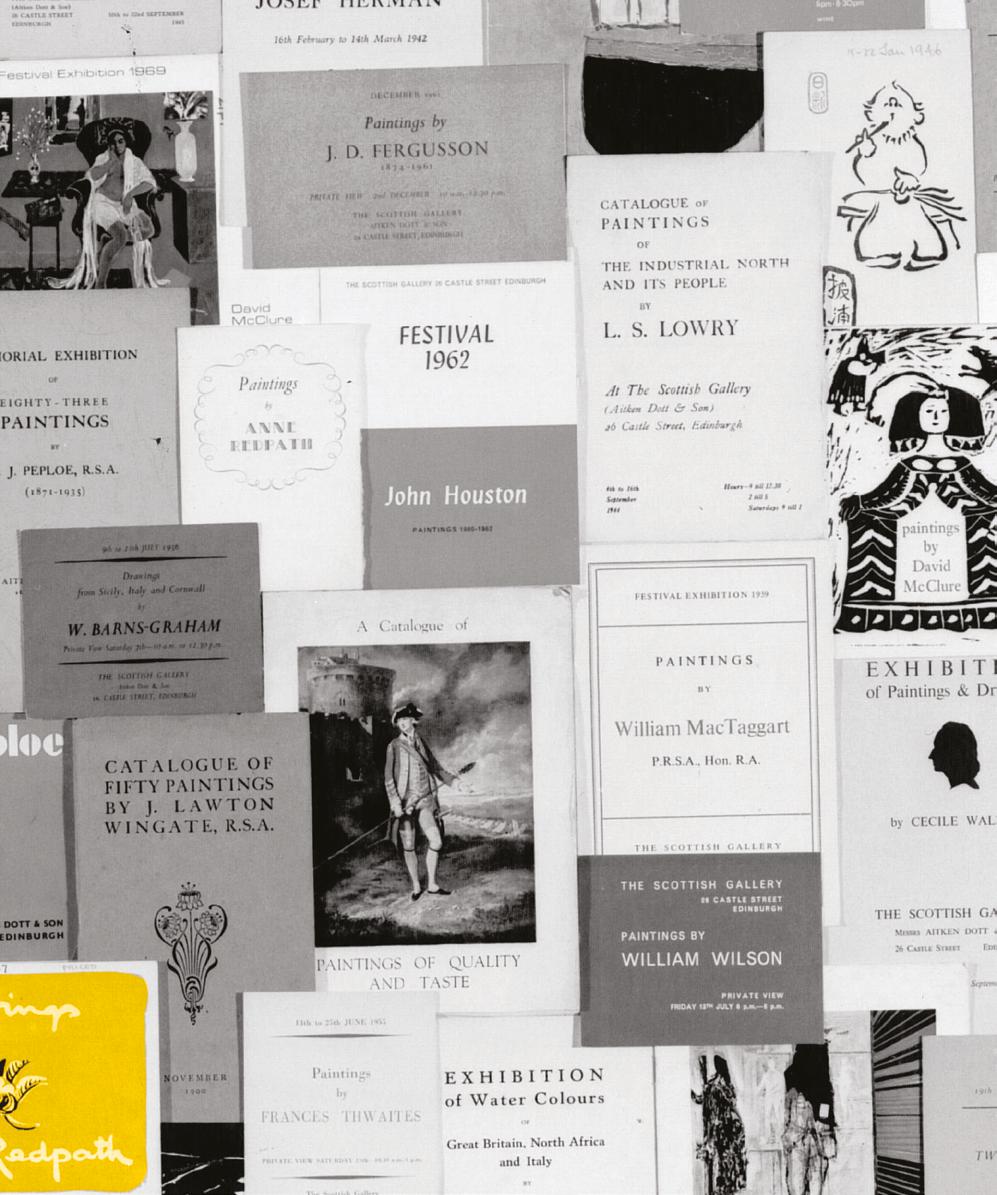

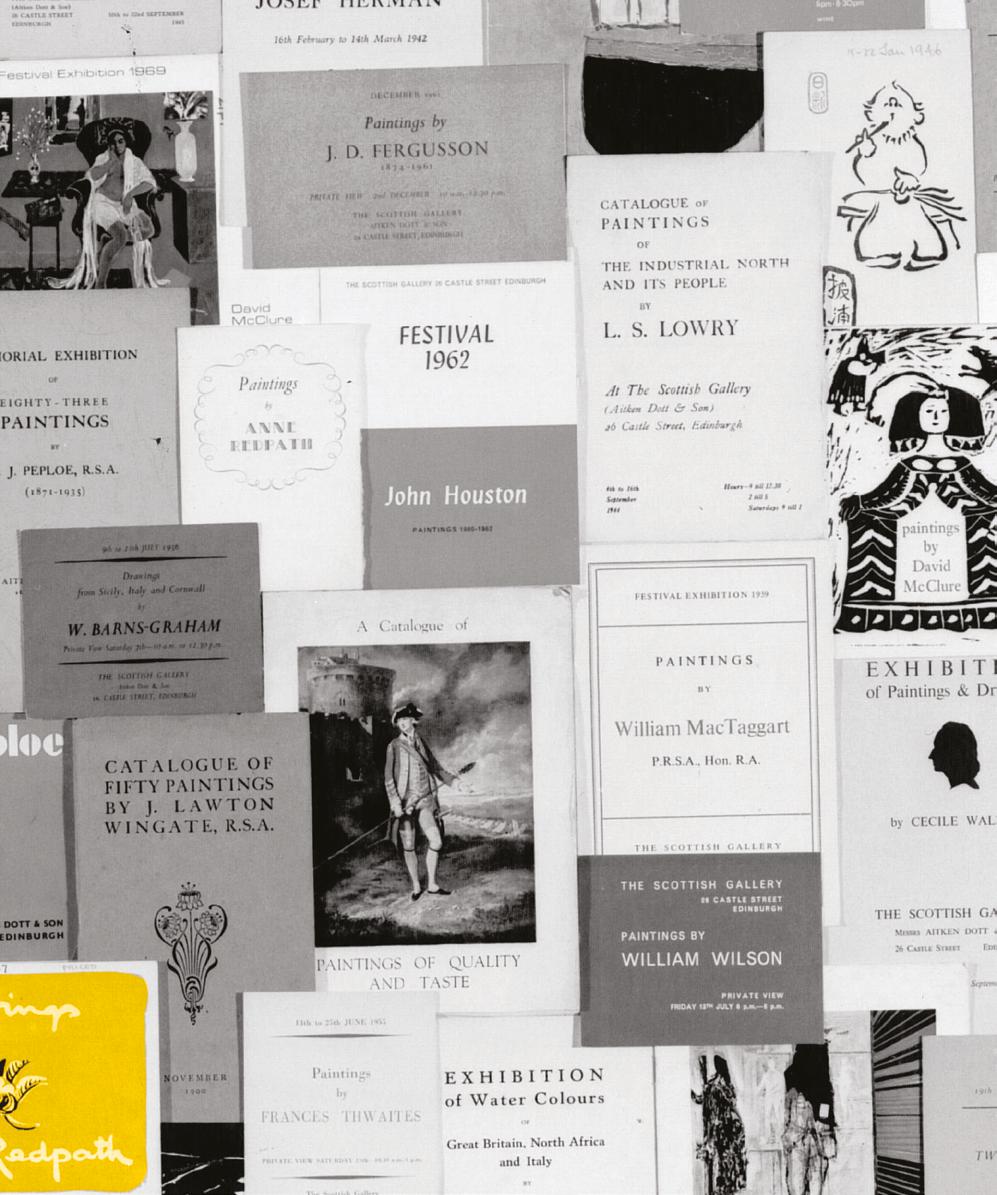

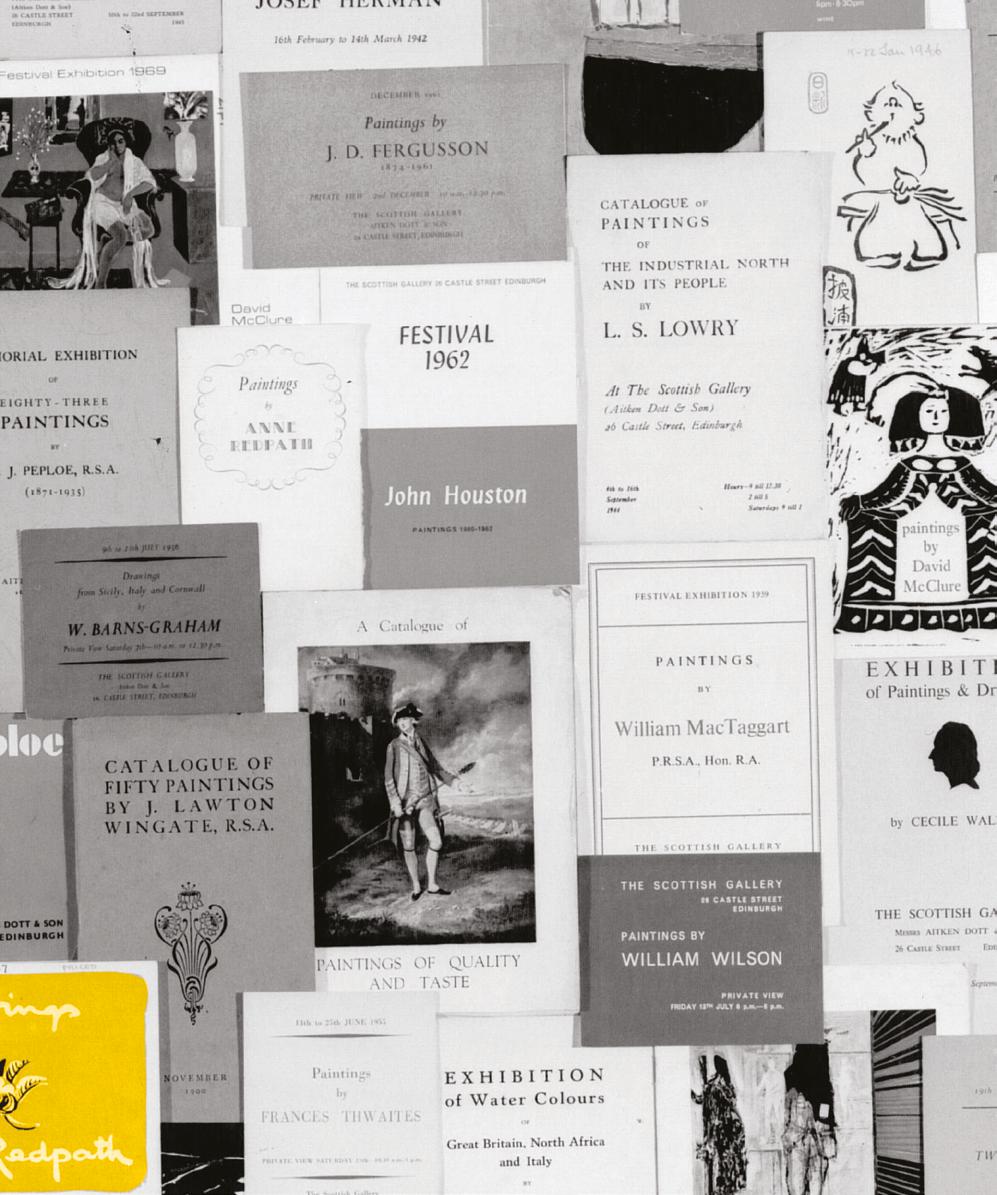

One of the great privileges of the Modern Masters series is the opportunity to delve into each artist's creative journey: who they are, where they lived, what defines their practice, why their work is relevant, who their contemporaries were and where they exhibited. The origins of these artists are presented on the following pages, offering a glimpse into the rich tapestry of Scottish art. This edition also includes a section on Printmaking, tracing its roots and its place within The Gallery, which reflects a vital, enduring tradition within Scottish art history.

We open our latest edition with a selection of works by Robin Philipson (1916-1992), a pivotal figure of the Edinburgh School, former Principal of the Edinburgh College of Art (1960-1983), and President of the Royal Scottish Academy (19731983). To highlight Philipson’s significance and influence, we've included a vintage article by his fellow artist and ECA colleague James Cumming (1922-1991), written when the Edinburgh International Festival marked its 25th anniversary with a major art exhibition in 1972. Cumming provides a thoughtful overview of the Edinburgh School, tracing its origins, artists, objectives, and future. The development of the School and its key figures are intricately and historically layered, making it a rich topic for re-evaluation. If art can be likened to a river, then Edinburgh is a confluence where many tributaries meet. In this edition, we include artists who trained or taught at Edinburgh, Glasgow, Aberdeen and Dundee,

with works which reflect the diverse landscapes of Scotland—from the northeast, Highlands, Dumfries and Galloway, Fife, the Borders and the capital.

A significant contributor to Scottish art is Hospitalfield in Arbroath, a centre dedicated to contemporary art and ideas. Many artists from across Scotland's art schools have gathered there to study, teach, undertake residencies or who were Wardens, fostering new perspectives and collaborations. This centre is relevant as two former Wardens; James Cowie and Ian Fleming had a profound influence on the next generation of artists and their peers and contemporaries Joan Eardley, Robert Colquhoun, William Burns, James Cumming and Alexander Fraser.

Just as artists mirror the world we inhabit, uniting artists from across Scotland provides a compelling vision of the nation. Modern Masters is an exploration of the origins of Scottish art, and the road often leads directly back to The Scottish Gallery. Visit any auction house or public gallery in Scotland, and you'll find countless works bearing an Aitken Dott or The Scottish Gallery label. We have demonstrated over nearly two centuries, a deep, long-standing connection with artists and our exhibitions demonstrate a steadfast commitment to the artist, presenting the latest studio developments. Our exhibition history is unparalleled in Scotland.

Christina Jansen | The Scottish Gallery

Edinburgh School | A Unique Record of Distinction by James Cumming, 1972

To mark the 25th anniversary of the Edinburgh Festival (1972), the Governors of the College have chosen to mount a major Retrospective Exhibition at Lauriston Place. The Edinburgh School does stand for something. The period to be covered is from 1947 to 1972. Twenty-five years is not a long time, seen against this century, but viewed as a synopsis of the contribution of the Edinburgh School since the end of WWII it will undoubtedly provide interest - critical or otherwise. As a training ground for artists and as an intellectual arena essential to a creative art education, the College has never been found wanting. It is both significant and salutary that Edinburgh has long enjoyed a pedagogic reputation. Between the Wars, among the staff selected to teach and lead in drawing and painting, D.M. Sutherland, David Allison, Adam B. Thomson, Henry Lintott, Penelope Beaton, William Gillies, John Maxwell, William MacTaggart, Donald Moodie and R.H. Westwater were highly esteemed for their working influence and counsel.

Post-war Development

After WWII, the staff who remained at the College were joined one by one to form the present staff under William Gillies, Head of Painting. The nucleus of the Edinburgh School as it is today thus created. 1946 began all of it, and events of distinction for the School and its subsequent achievements can properly be traced to that time. Students had all the liberty and often the protection they needed for studies leading to

creative output. Encouragement was always about and stimulus buoyantly present. The permeating atmosphere was lively, active, and hopeful. By the 1950s standards had been set and surpassed, and if the peak decade was perhaps the 1960s this was due in no small measure to the integrity, style and reputation that were recognisably established during these fruitful years. At Aitken Dott’s The Scottish Gallery, the combined powers of Anne Redpath's innumerable one-man exhibitions, and the equally prolific, stimulating shows by William Gillies, were reinforced by the generous output of

Anne Redpath with fellow students at Edinburgh College of Art, c.1915. Courtesy of the artist’s estate

William MacTaggart and the rarer, sensitive works of John Maxwell. The Royal Scottish Academy throughout the 1950s and 1960s enjoyed its reputation of exhibiting annually the work of the

nation's best artists, and distinguished visitors to the Edinburgh Festival were not slow to point out, even in print, the high quality of the work on view. William MacTaggart and William Gillies, for their achievements as painters as much as for their services to art education, received knighthoods. Of the artists who formed the Edinburgh School at its inception, it should be mentioned that but for Adam B. Thomson and William Gillies, who were Presidents of the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolours in turn, the influence of the School on painters in this somewhat difficult medium

might not have been so marked as it is today. The RSW has changed much in character, style, and liveliness over recent years, and many believe it to be one of the best watercolour exhibitors now in Britain.

A Sustained Vitality

As artists live in three generations like everyone else, it will be evident from a study of the present College prospectus that a fairish number of established artists of the Edinburgh School remain pedagogically active and executive. To have tutored over twenty years and not less than ten, places them in the middle generation, and their collective influence moulds as well as modifies new concepts and attitudes of contemporary students. To recognise that the international mind and conscience has become increasingly more liberal is to go a long way to understanding the vast differences in attitude and make-up which distinguish students now from those of twentyfive years ago. Yet they still remain educable,

Wihelmina Barns-Graham in her Edinburgh studio, c.1937. Image courtesy of the Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust.

William Gillies in his Edinburgh College of Art studio, c.1952

Robin Philipson in his Edinburgh College of Art studio, 1969

and talents show no sign of diminishing. While standards are maintained, the vitality of the School continues everywhere. Under the present Head of Painting, Robin Philipson, students have a breadth of counsel from a wide variety of sources. Among the names of painters involved in teaching in the College today are David Michie, Denis Peploe, William Baillie, John Houston, Alex Campbell, Robert Callender, Elizabeth Blackadder, John Busby, Hamish Reid, John Johnstone and Kim Kempshall. Significantly, reputations and lively teaching ideas join to exert what influence remains of the notion that a sound art education is an academic one and has compensatory rewards. It is this distinguished staff who bear responsibility as educators to maintain some kind of equilibrium in a confusing welter of styles, idioms and avant-garde trends which constitute today's world art.

The New Generation

New trends in the arts are frequently condemned for their banality, their failure to communicate, their lack of spirituality, or simply their inadequacy to please. It is in the tradition of painting, as with sculpture, to present with varying degrees of intensity works which are clear, visual images of sensuous experience. Feelings and sensations recorded, described, or expressed have constantly been the intention and resolution of artists throughout the century. Such art is best described as humanistic. Under William Gillies and Eric Schilsky, students were orientated by and large towards studies from nature using the life

model, common to both painting and sculpture and for purposes exclusive to painting, the still-life group or landscape. The more sensitive interpretations from such subject matter were encouraged. The pursuit of these studies enabled students to discover for themselves personal disciplines they might lack, and by taking steps to remedy their defects they gained a confidence in natural skills, emerged humanistic in style and figurative in their outlook. It was a satisfying continuous process. The sights of today's students are set differently. Their involvement with the essential disciplines of drawing is the same. Studies from life remain the concern of painters and sculptors alike but concepts have changed. Ideas often supersede arrangement. More direct influence comes from different trends in international art.

James Cumming (1922-1991)

Studied at Edinburgh College of Art. His work has been widely exhibited at home and abroad and is represented in many important collections. He was a frequent contributor to television and radio and was a member of the National Broadcasting Council for Scotland.

Edited extract from The Edinburgh Scene, 1972

Denis Peploe's Diploma Degree Show, Edinburgh College of Art, 1936

James Cumming and Willliam Mason at Edinburgh College of Art, 1939

James Cumming, Edinburgh, c.1980

photograph: Jessie Ann Matthew

Robin Philipson in his studio, 1970

Robin Philipson (1916-1992)

The Magician of the Brush

To meet Sir Robin Philipson was to encounter a man of charm and distinction, dressed slightly self-consciously in a bowtie and either a dapper, sometimes striped, jacket or else one splattered in paint. Conversation could range widely, revealing his interest in poetry as much as the visual arts to which he was making such a vital contribution. He can be considered to have been the most successful figure in Edinburgh’s art establishment in the third quarter of the twentieth century. Early on he had been elected a member of the Society of Scottish Artists and the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolour and in later life many honours would be bestowed on him. But it was as President of the Royal Scottish Academy for a full decade from 1973 that he made a deep mark in art officialdom, opening up new avenues and introducing its student exhibitions which continue to this day. As Head of the School of Drawing and Painting at the art college he maintained the ideals of the post-war Edinburgh School so concerned with expressive colour to which in temperament he was ideally suited: as an Edinburgh student in the late 1930s, his teachers had included William MacTaggart, Anne Redpath and John Maxwell. After the war Philipson became fascinated by the uncompromising expressionism of European painters, most famously Oskar Kokoschka. Although attracted to British abstraction and the inherent value of paint, he soon began to explore raw personal experience through developing specific themes which could combine aggression and violence with lyricism. This formed the bedrock of his career. Several paintings from these series from the 1950s to the 1980s (cockfights, cathedral interiors, war imagery, women and animals) are included in this exhibition, and they demonstrate a mature commitment to the pictorial: abstraction, where present, never dislodges representation of the world about us. He explores the human condition in many of his key academic paintings, tackling brutalism head on. His paintings, informed by what war can do and constructed with

passion, are never easy but have an important niche within British art. Man’s inhumanity to man is explored in another key series, where political and resultant emotional values are played out. These major works were the result of constantly rethinking the delicate balance between the empirical and the intuitive – a balance which is Scottish in its essence. At the same time, Philipson was one of the most lyrical painters of his generation, producing canvases which can convey the purest forms of beauty via traditional subjects and at times extraordinary colour choices. With his sensitive, serious temperament Philipson was a romantic but his work is essentially academic: apart from a commitment to subject matter, the potential and values of materials were important to him as to generations before him. For a period in the late 1950s he was one of the artists whose prints came off the St James Square presses of Harley Brothers, while as Head of Drawing and Painting he made sure not only that Edinburgh’s students had the opportunity to take printmaking as a final year diploma subject. His form of expressionism certainly gave him a lifelong commitment to the intrinsic values of art materials, sometimes straying from a standard oils palette. He experimented with help from the local paint manufacturer Craig & Rose who mixed a ‘Philipson blue’ for him as well as suggesting he use vinyl toluene to attach gold leaf – with the vinyl itself then becoming a common binding agent in his paint. However we see his art, its free handling, its meaningful decorative values and its sometimes dark subjects, it remains a serious investigation of life. For him the production of art was essential but brave. He once spoke of the dread of starting a studio day, of the waiting easel –but then good art is never an easy business.

Elizabeth Cumming Robin Philipson, Sansom & Co., 2018

Robin Philipson joined the King’s Own Scottish Borderers at the outbreak of war and was posted to India, later seeing action in Burma. His watercolour Nautch Girls is likely to have been worked up back in Scotland from original drawings. Nautch, meaning dance, was a tradition going back to Mughal times but had become corrupted during the Raj and associated with prostitution. Philipson’s dancers move in a circle, reminiscent of Matisse’s La Dance, but his woman are altogether more of the flesh, performing a dance but in their diaphanous drapes, partial clothes and nudity suggesting a strip-tease. Sexualised content was frequent in Philipson painting, but at a step removed, artist like viewer observers, making no value judgement.

Robin Philipson (1916-1992)

1. Nautch Girls, 1942 watercolour on paper, 24 x 34 cm signed and dated lower right

2. Bathers, c.1969 watercolour on paper, 25 x 18.5 cm signed lower right

EXHIBITED

Christmas Exhibition, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1969, cat. 128

Robin Philipson (1916-1992)

Robin Philipson (1916-1992)

3. A Talk in the Afternoon, 1970 watercolour on paper, 33 x 34 cm

EXHIBITED

Robin Philipson 100, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 2017, cat. 15; The Edinburgh School and Wider Circle, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 2019, cat. 53

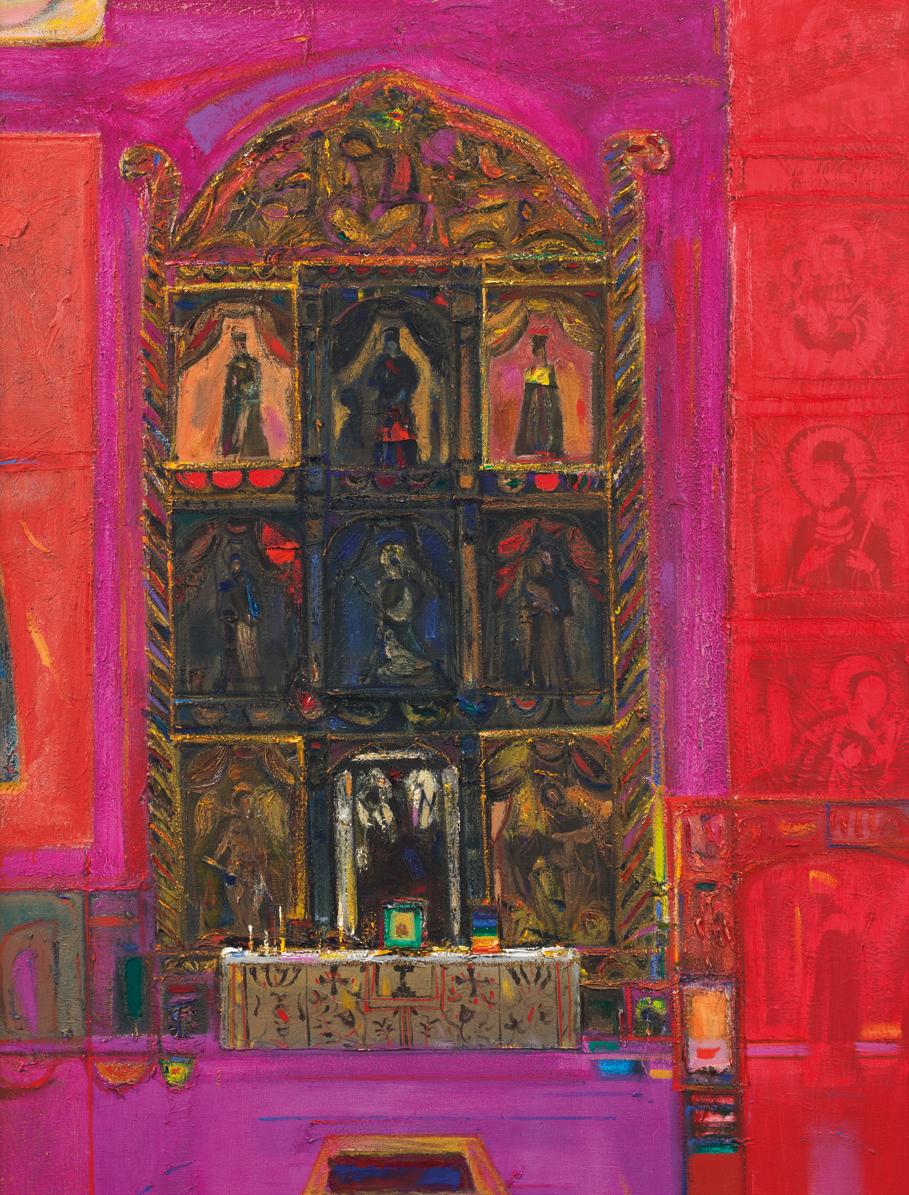

Philipson drew on religious imagery in several painting series: the gothic cathedral façade, primitive chapels in New Mexico, and the Iconostasis in Orthodox churches. Here, while the title tells us of the original inspiration, the artist plays with ideas of scale, the votive table dwarfed by the towering screen behind. As with much of his work the requirements of his composition in the abstract and ambiguities of space depth make the image defiantly ambiguous. However, the emotional punch is delivered by the colour, jewel-like in the details but framed by the sumptuous cardinal red of the panels on either side.

The Scottish Gallery exhibitions: 1954, 1958, 1961 (Festival), 1965 (Festival), 1968, 1970 (Festival), 1973, 1976 (Festival), 1983 (Festival) 1995 (Memorial), 2003, 2006, 2012, 2016 (Centenary)

4. Mexican Altar, c.1978 oil on canvas, 142 x 107 cm signed verso

EXHIBITED

Annual Exhibition, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, c.1978, cat. 50

Robin Philipson (1916-1992)

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the primitive chapels in New Mexico and the interiors of Byzantine churches provided a rich source of inspiration. The masterly arrangement of his composition, and use of both smooth and rich impasto, are deployed in Mexican Retablo. The inspiration is a recalled look at a church interior, but here he has deliberately avoided the suggestion of special depth, allowing colour, tone and surface to create visual interest in two dimensions.

Robin Philipson (1916-1992)

5. Mexican Retablo, c.1975 oil on canvas, 76 x 76 cm

Robin Philipson (1916-1992)

6. Towards Night, 1978 watercolour on paper, 79 x 70 cm

7. Dawn, 1978 watercolour on paper, 79 x 68 cm signed, titled and dated label verso

Robin Philipson (1916-1992)

8. Summertime, 1979 oil on canvas board, 30.5 x 30.5 cm signed, titled and dated on label verso

Robin Philipson (1916-1992)

Robin Philipson (1916-1992)

9. September Afternoon, 1978 oil on board, 32.5 x 39.5 cm signed, titled and dated verso

Robin Philipson (1916-1992)

10. Martyr 1, 1979 oil on canvas board, 23 x 23 cm signed, titled and dated on label verso

Robin Philipson (1916-1992)

11. Red Curtain, c.1979 oil on canvas, 61 x 61 cm signed and titled on label verso

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912-2004) p24

Mardi Barrie (1930-2004) p32

Jean Claude Bissery (b.1930) p34

Marj Bond (1936-2023) p36

Samuel Bough (1822-1878) p38

William Burns (1921-1972) p40

Peter Collins (1935-2023) p42

Robert Colquhoun (1914-1962) p46

Robert Hardie Condie (1898-1981) p50

James Cowie (1886-1956) p52

John Gardiner Crawford (b.1941) p56

Victoria Crowe (b.1945) p60

James Cumming (1922-1991) p64

Pat Douthwaite (1934-2002) p66

Joan Eardley (1921-1963) p70

Modern Masters XVIII

Ian Fleming (1906-1994) p78

Alexander Fraser (1940-2020) p84

William Gillies (1898-1973) p86

John Houston (1930-2008) p92

William MacTaggart (1903-1981) p98

David McClure (1926-1998) p102

James Morrison (1931-2020) p104

Lilian Neilson (1938-1998) p112

Denis Peploe (1914-1993) p114

S.J. Peploe (1871-1935) p122

Jean Picart le Doux (1902-1982) p124

James Spence (1929-2016) p126

Frances Thwaites (1908-1987) p128

Geoff Uglow (b.1978) p132

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912-2004)

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912–2004) was a leading member of the St Ives group of artists and made an outstanding contribution to the advancement of post-war British art. Last year, filmmaker and director Mark Cousins directed a new film A Sudden Glimpse to Deeper Things, which is a cinematic immersion into Wilhelmina Barns-Graham’s art and life. The film will be on general release in 2025. Wilhelmina, known as Willie, was born in St Andrews, Fife, on 8 June 1912. Determining while at school that she wanted to be an artist, she set her sights on Edinburgh College of Art, where she enrolled in 1932 and graduated with her diploma in 1937. At the suggestion of the College’s principal, Hubert Wellington, she moved to St Ives in 1940. Early on she met Borlase Smart, Alfred Wallis and Bernard Leach, as well as Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth and Naum Gabo who were living locally at Carbis Bay. Her peers in St Ives include, among others, Patrick Heron, Terry Frost, Roger Hilton, and John Wells. BarnsGraham’s history is bound up with St Ives, where she lived throughout her life. In 1951 she won the Painting Prize in the Penwith Society of

Arts in Cornwall Festival of Britain Exhibition and went on to have her first London solo exhibition at the Redfern Gallery in 1952. She was included in many of the important exhibitions on pioneering British abstract art that took place in the 1950s. In 1960, BarnsGraham inherited Balmungo House near St Andrews, which initiated a new phase in her life. From this moment she divided her time between the two coastal communities, establishing herself as a Scottish artist as much as a St Ives one. Wilhelmina Barns-Graham was represented by The Scottish Gallery throughout her career. Important exhibitions of her work at the Tate St Ives in 1999/2000 and 2005, and the publication of the first monograph on her life and work, Lynne Green’s W. Barns-Graham: A Studio Life, 2001, confirmed her as one of the key contributors of the St Ives School, and as a significant British modernist. She died in St Andrews on 26 January 2004.

The Scottish Gallery exhibitions: 1956, 1960, 1981 (Festival), 1989 (London), 2016, 2019, 2022

Whilhelmina Barns-Graham in her Barncroft studio, St Ives, c.1965

image courtesy of Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust

Barns-Graham’s simply designed line drawings, or latterly titled, Small Energy series, describes a series of elegant pen and ink drawings of fine, black, undulating lines created over a period of two decades.

I am beginning to think more about feeling & movement. The squares them [sic] worked on for years felt too rigid. Study of wave movements were a release.

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912-2004)

12. St Andrews November Afternoon, 1981 mixed media on card, 20 x 35 cm signed and dated lower right

PROVENANCE

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust

For a session of drawing, I may exclusively use linear ideas; an abstraction of what has been observed, first drawing a grid, building up a rhythm to allow the unexpected as curves or wave lines encouraging imagination and becoming creative. These rhythms suggest flowing forms, water, grass and wind movements, or lines for the pleasure of themselves. Paul Klee suggests, ‘We take a walk with a line’.

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, 1982

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912-2004)

13. Water Symphony, 1995 mixed media on card, 25.5 x 19 cm signed and dated lower right

PROVENANCE

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust

Throughout her career there was an ongoing dialogue in her work between outward observation and inward perception: direct drawing from life and distillation of colour and forms into abstract paintings. In her line drawings – a marrying of the two – Barns-Graham developed lines (as opposed to squares or circles) into space whilst also capturing movement of nature’s flows: wind, water, sand, sound and even glacier formations.

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912-2004)

14. Linear Development Blue, 1978 pen, ink and oil on card, 13 x 20 cm signed and dated lower right

PROVENANCE

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust

Mardi Barrie (1930-2004)

Mardi Barrie was an exact contemporary of Elizabeth Blackadder and John Houston and, like Houston, she came from Fife and attended Edinburgh College of Art from 1948. She went on to teach at Broughton School in Edinburgh. She exhibited widely, including latterly with the Bruton Gallery and the Thackeray in London as well as one-person and group shows with The Scottish Gallery. Like so many Edinburgh graduates she owes something to William Gillies, in particular his later oils when he employed a palette knife. Also, like Gillies, she eschewed strong colour, preferring earth tones, her work inhabiting a stygian world of dusk and shadow. But, in A Side of the Valley, Evening Light her landscape is more classically composed with foreground interest in grasses, a middle ground suggesting water or marsh and a low, snowy hillside, dark under the evening sky.

The Scottish Gallery exhibitions: 1968, 1972, 1979, 1983, 1988

Mardi Barrie (1930-2004)

15. A Side of Valley, Evening Light, c.1983 acrylic on board, 46 x 59 cm signed lower centre left

EXHIBITED

Mardi Barrie, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1983, cat. 21

Mardi Barrie, c.1981

Jean Claude Bissery (b.1930)

Jean Claude Bissery was a professor during the 1960s and 1970s at the National School of Decorative Art in Aubusson, France, alongside Jean Picart le Doux (cat. 62). This tapestry, woven on a Jacquard loom, reflects the more abstract tendencies of the late 1970s. The town of Aubusson, located in the Limousin region, is renowned worldwide for its tapestries, with a history of tapestry-making dating back to the 14th century.

Jean Claude Bissery (b. 1930)

16. Aurore, c.1970 tapestry in wool for Aubusson, 79 x 201 cm signed within the weave

Marj

Bond (1936-2023)

Marj Bond is known primarily as a figurative painter using strong poetic and symbolic elements within her practice. Born Marjorie May McKechnie in Paisley, she excelled in art during her school years, consistently winning the art prize at Paisley Grammar every year. Before embarking on her studies in 1955 at Glasgow School of Art, she assured her mother, who was by then widowed, that she would complete her teacher training to give her something to fall back on. She took drawing and painting with sculpture, when her tutors included the celebrated artists Alix Dick, Mary Armour, David Donaldson and Benno Schotz. But, true to her word, she did train as a teacher and moved to Uist in the Outer Hebrides. This was at a time before all the causeways had been opened and her commute between schools

involved travelling on the back of a tractor at low tide. She also learned to speak Gaelic, defying the residents who broke into their mother tongue as soon as she walked into the local shop. In her mid-career, she had made a home and studio in Fife.

Edited extract from her Obituary by Alison Shaw for The Scotsman, 2023

Much of Marj Bond’s work was inspired by travel and Celtic influences. In The Petroglyph, Cairnryan the artist had depicted the Petroglyph’s in the foreground which speaks of the ancient landscape. Cairnryan is a village in Dumfries and Galloway, which lies on the eastern shore of Loch Ryan, six miles north of Stranraer.

Marj Bond (1936-2023)

17. The Petroglyph Cairnryan, 1977 oil on board, 39 x 51 cm signed and dated lower right, titled on label verso

EXHIBITED

The Torrance Gallery, Edinburgh, 1977

Samuel Bough (1822-1878)

Samuel Bough was born in Carlisle in relative poverty, but was not discouraged by his artisan parents from an artistic life. He painted a charming picture of a cricket match at Carlisle held at Tullie House Museum and moved to Glasgow in his early twenties, initially earning a living as a scenery painter. He was inspired by the work of J.M.W. Turner, which he would have seen on visits to London. He was encouraged to paint landscape by Daniel Macnee and Alexander Fraser, working with the latter in Cadzow Forest in Ayrshire, staying from 1951 for two years when his painting combined genre elements with sunlit landscape. Duncan MacMillan writes (Scottish Art 1460-2000, p.230) how he was influenced by Horatio McCulloch, quarrelling with the older painter after he moved to Edinburgh, a quarrel in which the artists’ dogs also took sides.

Unloading the Catch, Newhaven

His admiration of Turner emerged with his most successful later subject, coastal scenes. He was not restricted to Scotland, painting in London and extensively in the north of England but it was drama of the Scottish coast to which he returned, the great seas, skies the activity of shipping and the bustle of human activity on the quays. In larger works like St Andrews (Noble Grossart) and The Rocket Cart

Samuel Bough (1822-1878)

18. Unloading the Catch, Newhaven, 1861 oil on board, 22 x 30 cm signed and dated lower centre

PROVENANCE

Long-term loan National Galleries of Scotland, 63182

(Kirkcaldy Museum and Art Gallery) we see an artist embracing the complexity of detail in genre, or narrative works. This is no less true in Unloading the Catch, Newhaven and this and many of his most successful and ambitious paintings seem as much in the tradition of David Wilkie as McCulloch, as well as rivaling Wilkie in the delivery of character and purpose in his painted figures. Under a benign sky the herring fleet is in, with boats tied up to the quay, where a man stands in the stern of a Fifie which still has its lug sail hoisted and three fishwives lean forward to receive the catch. The painting has the pictorial sophistication and strong colour praised in the next generation of Scottish painters, the pupils of Robert Scott Lauder at the Trustees Academy, like William McTaggart and George Paul Chalmers, and has some modern elements. The boat entering the harbour and composition on the left is similar to the truncated racehorses deployed by Degas twenty or so years later. The painting is full of observation in detail while all is enlivened by a consistent, sparkling light source from the west.

A sister picture, of identical size is also held at Tullie House in Carlisle, and another Newhaven subject was exhibited at the RSA in 1856, entitled Newhaven Harbour, During the Herring Fishing, one of 216 works he exhibited at the RSA in his lifetime.

William Burns (1921-1972)

William Burns was born in Newton Mearns, Renfrewshire and studied at Glasgow School of Art from 1944-48 under Ian Fleming and David Donaldson before attending Hospitalfield Art College when Fleming was Warden. Burns continued to work from Glasgow until 1954. Burns served in the RAF during WWII and retained his passion for flying after. Viewing the world from above had a profound effect on his practice leading to more abstract works. He relocated to Aberdeen as a Lecturer in Art Education at Aberdeen College of Education and later became Principal Lecturer and Head of Department. His life was tragically cut short on a flying excursion over the northeast in 1972.

Burns would often accompany Fleming on his painting excursions on the northeast coast. Both artists had an affinity for the fishing villages, communities, ship building, harbours, and the vast expanse of the North Sea. Fleming painted a portrait of Burns between 195054, which hangs in Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums – the artist sits in the foreground, holding his brushes with canvases and frames behind and to the left is a view of a northeast fishing village, probably Arbroath, with two figures with their backs to the viewers, looking out to the sea.

When Ian Fleming became Warden at Hospitalfield (1948-1954) his influence became evident on fellow artists who attended the school, in particular William Burns. Burns first attended Hospitalfield in 1948 from Glasgow School of Art and quickly acclimatised to painting his surroundings in Arbroath.

A review of the exhibition of Hospitalfield’s students’ work from that summer in The Arbroath Herald proclaimed: Burns’s work has a sensitivity of colour treatment that has captured the intrinsic quality of the scenes

and buildings he has sought to depict. During this period, many parallels existed between Fleming’s and Burns’s paintings. Not only did both artists seek comparable subjects at the Arbroath harbour and in Scotland’s coastal towns, but both valued similar stylistic qualities. For example, both Burns and Fleming used a tonal palette to explore the effects of light and shadow and emphasise structure and form. When Burns became a lecturer at Aberdeen College of Education in 1955, he settled 45 miles north of Arbroath in the fishing village of Portlethen. Although the coastal environment continued to inspire his work, the aesthetic through which he interpreted the landscape shifted from representation to abstraction. Like the English painter Peter Lanyon, Burns’s passion for flying informed his work, with many of his paintings capturing the essence of the landscape as viewed from above. Although his career was cut short, Burns’s legacy is preserved in his dynamic evocations of the northeastern coast, images whose origins can be traced to his time in Hospitalfield.

Edited extract from Peggy Beardmore, Students of Hospitalfield | Education and Inspiration in 20th Century Scottish Art, Sansom & Co., 2018

The Scottish Gallery exhibitions: 1964, 1966, 1968 (Festival)

Boatyard

Boatyard is likely to have been painted during a stay at Hospitalfield in the early 1950s. The deserted boatyard is eerily lit at what seems to be night-time. It is devoid of boats but full of visual interest created from texture and a satisfying balance of masses and unconventional design.

19. The Boatyard, c.1952 oil on board, 60 x 90.5 cm signed lower centre

PROVENANCE

Paintings in Hospitals

William Burns (1921-1972)

Peter Collins (1935-2023)

Peter Collins was born in Inverness in 1935 into a distinguished medical family. He studied at Edinburgh College of Art from 1952-58, enjoying post-diploma study and the prestigious Andrew Grant Scholarship. He subsequently taught at Duncan of Jordanson College of Art in Dundee and gained professional honours becoming an RSA and having work included in many public collections. His work is hard to characterise and includes several major portrait commissions, as well as work in frank acknowledgement of Picasso and Matisse. His style varied also from a superrealism deployed to depict an enigmatic, personal surrealism and broader techniques used as he saw fit for his subject. Collins had strong opinions on many things which made him a fascinating and sometimes challenging interlocutor and in the 1980s he began a period of intensive research on a number of Italian old master works he believed might have been misattributed. The Mantegna which Sir Timothy Clifford tried to acquire for the National Gallery of Scotland exercised his considerable critical appraisal in particular.

Peter Collins exhibited with The Scottish Gallery in 1968.

Lemons (cat. 20) is an early work and an unusual and successful essay into still life. The gatefold table creates a playful motif to define a shallow space for his sparse still life and its suspended leaf the compositional drama. Homage to Raeburn (cat. 21) belongs to a later period and seems a deliberately perverse piece of mundane subject matter, an eloquent defence of the artist’s right to choose what ever subject he chooses. It is painted beautifully in a narrow range of colour and tone while the title surely is a double pun of Raeburn’s technique and the brand of the fireplace which forms the subject.

Lemons | Homage to Raeburn

Peter Collins at work in his younger years, c.1960

PROVENANCE

The Artist’s Estate

Peter Collins (1935-2023)

20. Lemons, c.1969 oil on canvas, 101.5 x 76 cm signed lower right, titled verso

Peter Collins (1935-2023)

21. Homage to Raeburn, 1997 oil on canvas, 45.5 x 56 cm signed, titled and dated verso

EXHIBITED

Annual Exhibition, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, 1997

PROVENANCE The Artist’s Estate

Robert Colquhoun (1914-1962)

Robert Colquhoun was born in 1914 to working class parents from Kilmarnock, Ayrshire. His art teacher, James Lyle, helped him win a scholarship to Glasgow School of Art (1933-1937), and he then won a travelling scholarship to France and Italy along with his lifelong friend, lover and companion, Robert MacBryde with whom he is largely associated. Solo exhibitions under the guidance of Duncan MacDonald at the Lefevre Gallery on Bond Street were sell out sensations and the phrase The Golden Boys of Bond Street was coined. During this high period, Colquhoun and MacBryde showed in The Scottish Gallery, 1944, Paintings by British & French Artists. Colquhoun later became a master of the monotype technique as he slowly moved away from the canvas. Success post 1951 saw The Roberts, as they were known to their friends, fall into a sharp decline into a life of poverty. Robert Colquhoun died in 1962.

Life Drawing

The first of the two life drawing studies (cat. 22 and cat. 23) were undertaken as a student at Glasgow School of Art (1933-1937). The second life study is likely to have been completed during his time under James Cowie (1886-1956) when staying at Hospitalfield, Arbroath in 1938. Despite not enjoying the Cowie’s strict teaching, his drawings shifted in style. In Life Drawing, 1938 (cat. 23) the tonal shading on the left hand and the delicate outline on the arms and lower torso, shifts the balance and focus and lifts the whole drawing.

The Scottish Gallery exhibitions: 1944 Colquhoun & MacBryde participate in Paintings by British and French Artists, Lefevre Gallery, London and which also tours to Aitken Dott & Son (The Scottish Gallery), Edinburgh. The Roberts, 2010 Golden Years, 2014 The Roberts, Revisited, 2017

Right: Front Cover: Photographs of Robert MacBryde and Robert Colquhoun by John Deakin (1951) courtesy Vogue/© The Condé Nast Publications Ltd; Left Robert MacBryde Right Robert Colquhoun Cover of The Roberts, The Scottish Gallery, 2010

Robert Colquhoun (1914-1962)

22. Female Nude, c.1936 pencil on paper, 34 x 23 cm signed lower right

23. Life Drawing, 1938 pencil on paper, 38 x 18 cm signed lower right

Robert Colquhoun (1914-1962)

Robert Hardie Condie (1898-1981)

Robert Hardie Condie (1898-1981)

24. Autumn in Glenesk, c.1960 watercolour on paper, 33 x 41 cm signed lower left

Robert Hardie Condie (1898-1981)

25. Weekend Off, Pittenweem, c.1955 watercolour on paper, 31 x 41 cm signed lower left

James Cowie (1886-1956)

James Cowie was one of the finest draughtsmen of his generation: drawing was the very essence of what he did, but his drawing was never showy, no mere display of virtuosity like the work of Augustus John, for instance, which he loathed. Rather for him drawing was a way of raising something observed into a visual idea that has its own energy and integrity on the page and subsequently, too, on the canvas, for he always worked through drawing to painting. Nor is it fanciful to put it that way, it merely paraphrases his own words; to copy nature, he said, is to me not enough for a picture, which must be an idea, a concept built of much that in its total combination it would never be possible to see and to copy. Such a stern ambition took a great deal of thought and so he worked out his ideas on paper. He made studies for compositions to be painted and of figures and other details that occur in them, but also too of things that simply caught his eye. He did make drawings that are compositions in themselves, especially latterly when he was inspired by the enigmatic work of the surrealists, but even when an idea eventually became a finished watercolour, he made numerous preparatory drawings. Duncan MacMillan, 2015

Hosptialfield, Arbroath

For much of the last century, Hospitalfield, the Victorian house on the outskirts of Arbroath has been a unique place of education, debate and exchange for young artists in Scotland. Around 700 artists have passed through its

doors. Alumni including Joan Eardley, John Byrne, Peter Howson and Roberts Colquhoun and MacBryde, to name a few. In 1935, the Patrick Allan-Fraser Trust Scheme was launched: the house would be run by an artistwarden, and a small number of genuine and meritorious students of drawing and painting would be selected from each of Scotland’s art schools for an intensive residential summer school. Two years later, the first students arrived, and the artist and art educator James Cowie was appointed the first artist-warden. He remained in the post until 1948 and painted his masterpiece, The Evening Star, during the war years in the studio at Hospitalfield. Cowie and his successor Ian Fleming, Beardmore writes, led by example and encouraged students to pursue practices that aligned with their own affinities. Their influence on many students of the time is clear, and for those who preferred a different approach, there could be colourful disagreements. Joan Eardley, at Hospitalfield as a student in 1947, worked in a loose expressionist painting style very much opposed to Cowie’s classicism. I think I will have to be very strong, she wrote to her friend Margot Sandeman from Arbroath, to stand against Mr Cowie.

Extract from Susan Mansfield, Hosptialfield: the institution that’s shaped many a fine artist, The National, 2018

The Scottish Gallery exhibitions: 1956 (Memorial), 1986 (Retrospective), 2015

James Cowie (1886-1956)

26. Two Casts, c.1944 pencil on paper, 38 x 34.5 cm signed lower right

EXHIBITED

The Scottish Gallery Collection, Riverside Gallery, Stonehaven, 1992

27. Study of a Schoolgirl, c.1930 pencil on buff paper, 48 x 20 cm signed lower left

James Cowie (1886-1956)

James Cowie (1886-1956)

28. Study of a Schoolboy, c.1935 pencil on buff paper, 40 x 19 cm signed lower right

John Gardiner Crawford (b.1941)

There is no shortage of subjects within a few miles of Crawford’s home in Arbroath. He is attracted to the marchlands where sea meets land, where low buildings are scoured by wind and sand, where a lighthouse gives succour to a seafarer’s eye, where the chance order of a row of seagulls or reflection on a cottage window makes us pause, think and wonder. He paints the wilderness of the North Sea, lent significance by the fisherman’s blood that runs in his veins.

Guy Peploe, 1998

John Gardiner Crawford was born in Broadsea by Fraserburgh where his father and forefathers were all Broadsea fishermen. After Fraserburgh Academy, Crawford studied at Gray’s School of Art, 1959–64, including a postgraduate year, and at Patrick AllanFraser School of Art, Hospitalfield, Arbroath. He was made a member of RSW in 1974, RBA in 1983 and RI in 1984. He exhibited with The Scottish Gallery in 1982 and has held several one-man exhibitions with The Gallery. His work is held in numerous public collections.

The Scottish Gallery exhibitions: 1982, 1985, 1987, 2003, 2006

John Gardiner Crawford, Arbroath, 1981 photograph: Jessie Ann Matthew

John Gardiner Crawford (b.1941)

29. Cliff Sheltered, 1997 watercolour on paper, 35.5 x 48 cm signed lower left

30. Lunan Beach, 1988 watercolour on paper, 31 x 43.5 cm signed lower left

John Gardiner Crawford (b.1941)

Victoria Crowe (b.1945)

Venice has become a second home for Victoria Crowe. Nowhere better is found the living balance between history and the present, where civilisation is least airbrushed and culture rich and layered. It is a place of the possible, at once fragile and robust, immutable and shifting.

The Scottish Gallery exhibitions: 1970, 1973, 1977, 1982, 1995, 1998, 2001 (Festival), 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010 (Festival), 2012, 2014 (Festival), 2016, 2018 (Festival), 2019, 2021, 2023, 2025 (Festival, 80th)

Victoria Crowe (b.1945)

31. Assembled Fragments - Gold, 1998 mixed media, 72 x 33 cm signed lower right

EXHIBITED

Victoria Crowe - New Paintings, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1998, cat. 31

The practice of an artist using his or her own family as models is commonplace and often a mere expedient. For Victoria Crowe, however, the painting of her daughter Gemma made in 2000 is a significant painting for the artist and her family. It was not long after the tragic death of Gemma’s big brother Ben and the sitter has a cool defiance that looks forward as well as back. The setting of Italy is also significant being the place where Crowe found the milieu to reengage with new material in the psychological locus of her genesis as a painter. The carmine palette and quattrocento sensibility are both new and familiar, her painting a palimpsest: accreted layers of time and emotion. Gemma seems to stand in a chamber, veiled on her right while behind, a figure of the Virgin Mary holds a rose without thorn - a symbol of purity. On her left a strong shaft of yellow light lends a glow to her skin, while a renaissance beauty in profile stares in with indifference.

Victoria Crowe (b.1945)

32. Portrait of a Young Woman, Milan, 2000 oil on canvas, 51 x 66 cm signed lower left, titled verso

EXHIBITED

Victoria Crowe - New Work, Edinburgh Festival Exhibition, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 2001, cat. 36; Victoria Crowe: Beyond Likeness, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh, 2018

James Cumming (1922-1991)

As a painter, James Cumming was possessed of a singular and highly personal vision. Several phases of interest took place in his work, Still Life, Portraits, Space Age, Puppets, Circus and the Electron Microscope brought forth another series of works concerning the visual nature of living cells. The hand of the draughtsman is always very much in evidence, an assured line in absolute control of the formal arrangement.

James Cumming was born in Dunfermline and studied at Edinburgh College of Art. In the early 1950s a travelling scholarship took him for a year to Callanish on the Isle of Lewis leading to his acclaimed series of Hebridean paintings. His considered and meticulously wrought style became concerned with geometry, structure, and abstraction. He also began to lecture on a regular basis at Edinburgh College of Art from 1950. Whilst artist in residency at Hospitalfield in Arbroath in 1960-61, his work and language in abstraction had a significant impact on John Byrne and Alexander Fraser. His most distinctive work of the 1960s is rich in colour, where it is employed, but essentially tonal. His later career was more concerned with natural and cellular forms, vibrant colour and a more prominent geometry.

The Scottish Gallery exhibitions: 1962, 1971, 1972 (Festival), 1985 (Festival), 1995 (Memorial)

L’Entracte

While most of his contemporaries finishing their Diplomas at a Scottish Art College sought a post-diploma placement in Italy or France, James Cumming spent a year on the Isle of Lewis after completing his studies, interrupted by War service, at Edinburgh. In this time, he developed a highly personal style to depict island life, in winter confined to ill-lit cottages and pubs. L’Entracte, the interval, sees the band perhaps about to resume their set, a stout figure on the right in Glengarry and with an accordion slung over his neck. To his left a second figure is more difficult to read, perhaps seated, Braque violin over his shoulder, cigarette in his mouth as he speaks to someone outside the frame of the setting. The painting functions as entirely abstract, but Cumming has included enough real observation to take us to the smoky venue, half the village in attendance, the long nights and howling winds outside forgotten.

James Cumming (1922-1991)

33. L’Entracte, 1957 oil on board, 68.5 x 57 cm signed and dated lower left

Pat Douthwaite (1934-2002)

Pat Douthwaite was born in Glasgow in 1934. From the age of four, possibly earlier, she showed no interest in her sibling brothers. Her mother had been a hat designer prior to her marriage and Pat liked to fantasise with her mother’s hats, veils, feathers, jewellery and high pointed shredded pink silk dancing shoes and face make-up. She played this particular game of child theatre wandering about the long garden dressed in old gauze curtains wheeling a doll’s pram – no interest in dolls or toys as such, only wheeling the old kinder machine with kittens in it, tucked in with old blankets. As an adult, Douthwaite is a painter with an exceptional gift of externalising her own fantasy world, filling and quickening a two-dimensional space with nervously vital lines and emotionally expressive colour. Whether her subjects are legendary women – and these, like Theda Bara, Belle Starr, Amy Johnson, have been recurrent obsessions – or a shivering, cowering dog, or a palm tree sorely out of its element in an alien, northern winter, Douthwaite seems to find it necessary, like a method actress, to inhabit the idea, to get inside the skin of the role, as it were. Her paintings, often grotesque for all their elegance, can range in mood from tragicomic frenzy to angst-ridden melancholy, but they usually have a certain exciting theatricality in common.

Cordelia Oliver, 1981

The Scottish Gallery exhibitions: 1977, 1993, 1995, 1998, 2000 (Retrospective 1960-2000), 2005 (Memorial), 2011 (Retrospective), 2014, 2016, 2020 (London), 2021

Woman in a Fur Coat

The female figure is a self-portrait accompanied by a dark, spiritual figure, who seems more like a companion than a grim reaper. Both figures are relaxed, as if observed in a waiting room suffused with a dirty yellow light with

a comically bent palm tree lending an exotic presence. Death references occur throughout the artist’s oeuvre but are seldom sinister, more often in the form of animated skeletal players in a pageant of life and death, in which both must be present but the living unafraid.

Prints | The Kabuki Series (cat. 79)

Pat Douthwaite had been a controversial figure on the Scottish Art Scene for more than thirty years before she came to Peacock in the late 1980s to produce a suite of lithographs. Originally studying movement, mime, and dance with Margaret Morris, she was encouraged to paint by Morris's husband, J.D. Ferguson. She came to work on the Apples Kabuki suite of lithographs during 1988. These very graphic prints influenced by traditional Japanese theatre hark back to Douthwaite's own dance training and the works capture the state of exaggerated costume and extreme theatre. The suite travels from very calm, beautiful portraits of kimonoclad women playing tennis to powerful, quite gruesome images of skulls and scarred victims, all resplendent in patterned finery and accompanied by birds and small cat-like animals. Recognised as the most complex of processes, the lithographs were made by the artist drawing directly onto a stone with a greasy crayon and wash.

Pat Douthwaite at Third Eye Centre, Glasgow, 1988

Pat Douthwaite and Henry Dooley, c.1985

Pat Douthwaite (1934-2002)

34. Woman in a Fur Coat, 1981 oil on canvas, 141 x 143 cm signed and dated lower left

EXHIBITED

Pat Douthwaite Retrospective, The Scottish Gallery at Art London, 2001; Pat Douthwaite – Memorial Exhibition, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 2005, cat. 16

ILLUSTRATED

Guy Peploe, Pat Douthwaite, Sansom & Co., 2016, pl. 65

Joan Eardley (1921-1963)

In the early 1960s Eardley recorded a taped interview, and spoke of her enthusiasm for the back streets of Glasgow and the children who played there: ‘The community feeling is rapidly disappearing in Glasgow... I do feel that there is still a little bit left. I try still to paint Glasgow so long as there is this family group quality. I’ve known about half a dozen families well I suppose during the period of time I’ve worked in Glasgow... about ten years or more and at the present moment a family by the name of Samson. I have been painting them for seven years... there are a large number of them, twelve, so I’ve always had a certain number of children from this family of any age I choose... some children I don’t like... most of them I get on with... some interest me much more as characters... these ones I encourage – they don’t need much encouragement – they don’t pose –they come up and say will you paint me? There are always knocks at the door – the ones I want – I try it get them to stand still – it’s not possible to get a child to stay still... I watch them moving about and do the best I can... the Samsons –they amuse me – they are full of what’s gone today – who’s broken into what shop and who’s flung a pie in whose face – it goes on and on. They just let out all their life and energy... and I just watch them and I do try and think about them in painterly terms... all the bits of red and bits of colour and they wear each other’s clothes – never the same thing twice running... even that doesn’t matter... they are Glasgow – this richness that Glasgow has – I hope it will always

have – a living thing, intense quality – you can’t ever know what you are going to do but as long as Glasgow has this I’ll always want to paint. Whenever I come back I get a new feeling –chiefly the back streets – I always feel the same – I want to paint them differently – but the same thing – you can’t stop observing, things are happening all the time – you are recognising them in your mind.

Fiona Pearson, Joan Eardley, National Galleries of Scotland, 2007

The Scottish Gallery exhibitions: 1955 (Festival), 1958 (Festival), 1961, 1964 (Festival and Memorial), 1981, 1983, 1984, 1988, 1990, 1992, 1996, 2007, 2013, 2015, 2017, 2021 (Centenary)

Left: The front door to Eardley’s Studio, at 204 St James Road, Townhead, Glasgow, April 1963. Photograph: Audrey Walker, Right: Joan in her Townhead Studio, c.1959. Photograph: Audrey Walker

Joan Eardley's Townhead studio, top floor, on the corner of McAlin Street and St James Road

Joan Eardley (1921-1963)

EXHIBITED

Joan Eardley Memorial Exhibition, Scottish Arts Council, 1964, cat. 49

35. Child in a Red Jersey, c.1952 pastel on glass paper, 22 x 14 cm signed lower left

Joan Eardley (1921-1963)

36. Glasgow Street, Rottenrow, c.1956 mixed media on paper, 6 x 14 cm

Port Dundas is an area of Glasgow north of the Clyde, on the Forth Clyde Canal, not far from Eardley’s studio in Townhead. The Eighteenth Century canal was a vital part of the city’s industrialisation, with the chimney stacks for distilling and power generation forming a distinctive part of the city skyline at the Port Dundas terminus. When Joan made her painting the area was in general decline and she has captured the tumult of industrial architecture, dereliction and a dirty sky with her distinctive brush strokes and palette.

Joan Eardley

(1921-1963)

37. Port Dundas, Glasgow, c.1950 oil on board, 28 x 34 cm

Three large canvases all worked throughout the day from my front door or thereabouts. It has been a perfect painting day – Not as regards climate! (I wore a fur coat for the first time). But for beauty quite perfect – A big sea – with lovely light – greyness and blowing swirling mists – and latterly a strong wind blowing from the south, blowing up great froths of whiteness off the sea, like soap suds onto the field behind our wee house – And towards evening the sun appeared shrouded in heavy mist – and turned yellow and orange and red, with great swirls of mist obscuring her every now and again – I wanted so much to paint the sun but it meant turning round and leaving my sea – or else running round paints and all to the other side of the bay. And I just hadn’t time or energy to do this – Tomorrow perhaps there will be the possibility of this sun again and I can take up my position, the other side, by the minister’s house. I think it could be good there.

Extract from a letter, Christopher Andreae, Joan Eardley, Lund Humphries, 2013

Grey Beach and Sky

Grey Beach and Sky was painted at the water’s edge of Catterline Bay. Eardley frames the left side of the composition with the high cliff bank above the boat shed, while to the right, we see the distinctive kale tap, a large rock formation anchoring many of her Catterline paintings. In front of the boat shed, two boats are depicted: the blue Linfall and the green Mascot, owned by local fishermen who, like Eardley, lived in cottages overlooking the bay. This tonal painting captures the drama of a winter storm, with the sky and sea mirroring each other in foreboding grey. The surf crashes against the beach with the pier engulfed by the energy of the North Sea swell.

Joan Eardley (1921-1963)

38. Grey Beach and Sky, 1962 oil on board, 56 x 107.5 cm signed and dated verso

EXHIBITED

Joan Eardley Centenary, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 2021, cat. 37

Ian Fleming (1906-1994)

Ian Fleming was born in Glasgow in 1906 and studied at Glasgow School of Art during the 1920s. He began printmaking at art school, where his skill was quickly noticed, with Glasgow Art Gallery purchasing two of his prints while he was still a student. He joined the staff at Glasgow School of Art in 1931 and soon met the Edinburgh-based printmaker William Wilson through their mutual acquaintance Adam Bruce Thomson. Wilson and Fleming struck up an important friendship, sharing views on printmaking technique and subjects, their influence on each other was of mutual benefit to both their practices. During his time at Glasgow School of Art Fleming painted a portrait of the two Roberts – Colquhoun and Macbryde – who were his students at the time (alongside a young Joan Eardley). During the War, Fleming served first as a reserve policeman before joining the Pioneer Corps seeing action in France, the Low Countries and Germany. He left the Army in 1946 as an Acting Major and returned briefly to Glasgow before taking up the position of Warden at Hospitalfield, Arbroath, succeeding the artist, James Cowie. The fishing towns of Angus and Kincardineshire were to be his inspiration for many paintings of this period in which he celebrated the

colour, forms and architecture of the working harbour communities. In 1954, he relocated to Aberdeen as Principal of Gray’s School of Art but continued to pursue his painting practice alongside his academic commitments. He was elected a full Academician of the Royal Scottish Academy in 1956, and by the time of his death was the longest-established member. After retiring in 1971, he became one of the founding members of Peacock Printmakers in Aberdeen, alongside Frances Walker.

The Scottish Gallery exhibitions: 1947, 1987

Ian Fleming with Gray's School of Art staff and students, Aberdeen, 1971. Photograph: Demarco Archive

Prior to becoming Warden of Hospitalfield (1948-1954), Fleming and his friend and contemporary William Wilson periodically travelled throughout Scotland to paint the landscape, but it was not until Fleming’s time in Arbroath that he began to paint the coastline in earnest, developing a particular fascination with the harbour. The more time Fleming spent observing the visual environment of Arbroath and engaging with its community, the more he found to explore through his artwork.

Details of the buildings are then reduced to increase the emphasis upon their underlying geometric structures. The sense of depth is also challenged, as the extreme tilting of the pier

in the foreground contradicts the perspective established in the mid-ground. In addition, the lifebelt and stand, which span the height of the images further emphasise the surface and twodimensionality of the image. This sense of twodimensionality reduces the harbour buildings, the harbour wall, and the life-preservers to geometric patches of paint. These paintings are representative of Fleming’s process of continuously reinterpreting the landscape through form and composition, a practice which would continue to develop during and following his time at Hospitalfield

Edited extract from Peggy Beardmore, Students of Hospitalfield | Education and Inspiration in 20thCentury Scottish Art, Sansom & Co., 2018

39. The Brown Sail, Arbroath, 1952 oil on canvas, 76 x 101 cm signed lower centre

EXHIBITED

Annual Exhibition, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, 1953, cat. 280

Ian Fleming (1906-1994)

Seawall No.1 is a monumental post-war painting that details the shielding strength, endurance, and protective power of Arbroath’s harbour wall. The small boat with the brown sail appears fragile as it sets out into the North Sea. A hallmark of a great Fleming painting is the minute human detail, just visible in the boat, which captures the vulnerability of man against the vastness of the sea.

Ian Fleming (1906-1994)

40. Seawall No.1, 1953 oil on board, 63.5 x 76 cm signed lower left, titled verso

EXHIBITED

Royal Glasgow Institute, 1963

Alexander Fraser (1940-2020)

Alexander Fraser was born in Aberdeen, where he trained at Gray’s School of Art under Robert Henderson Blyth. He began to find his own direction at Hospitalfield where James Cumming proved an inspirational tutor, setting impossible exercises in composition which were to have a lasting effect on the development. Alexander Fraser taught at Gray’s School of Art from 1966, becoming head of Drawing and Painting from 1987-1997. He was a hugely influential teacher and art educator. On retirement, he returned to full time painting and held several solo exhibitions with The Scottish Gallery. His late intricate paintings are both atmospheric and beguiling, offering the audience intriguing compositions of people, animals, architecture and landscapes. He drew inspiration from memories of travel and the history and folklore of his native Aberdeenshire, saying I paint my family and my environment transformed by myth.

The Scottish Gallery exhibitions: 1998, 2001, 2004, 2007, 2011

The relationships between Fraser’s figures are not intended to be ‘real’, but metaphorical and compositional, blending ideas of abstract depiction of volume with a disquieting sense of the surreal. Figures within boxes, such as Self Portrait in a Box opposite, suggest psychological disturbance. Like his fellow Aberdeenshire artist, James Cowie – Fraser clothes the everyday in the guise of the extraordinary.

Alexander Fraser (1940-2020)

41. Self Portrait in a Box, c.2011 oil on board, 15 x 19.5 cm signed and titled on label verso

Self Portrait in a Box

Alexander Fraser in the studio. Photograph: Gavin Fraser

William Gillies (1898-1973)

Sir William Gillies was the dominant figure of the Edinburgh School over which both his personality and his work had a quiet authority. He led by example at the College of Art, encouraging his students to experiment but from a firm grounding in looking, and of course practice, drawing in particular. He also selected his staff to reflect this ethos: men and women who had a similar independence but respected hard work, what William MacTaggart called the good habit. The duties of teaching for Gillies and many of his colleagues in the School of Drawing and Painting were combined with their own practice without conflict; being a professional painter: working and exhibiting, was understood as integral to the reputation and health of the School. Robin Philipson, Elizabeth Blackadder, John Houston, David Michie and James Cumming were the beneficiaries of this attitude, along with their students, quietly instilled by Gillies over his fifty years of influence.

I have been trying to pin down my thoughts on the great man. I do not find it easy. In a way he remains an enigma. I was a student for five years while Gillies was Head of Paintings and yet I had only three or four lessons from him in all that time. The first was when MacTaggart called for Bill Gillies to come and see a painting I had done. He admired it generously and commended it for its

William Gillies on the Lammermuirs, 1920s image courtesy of RSA

tonal values. I had on the easel a much more freely painted thing with apples and a jug. He looked at it and said Apples are not tennis balls. They have planes. He then proceeded to push the wet paint around with his horny thumb, making the apples truly three dimensional, and expressed in planes. On another occasion I was propounding a theory I had come across about Organic Colour Values… I asked him if he did not agree with this. His response was typically anti-intellectual. No. Nature always gets the colour wrong, so you have to try to improve it.

David McClure, quoted in W.G. Gillies by W. Gordon Smith, Atelier Books, 1991

The Scottish Gallery exhibitions: 1945, 1949, 1952, 1958 (Festival), 1963 (Festival), 1968, 1971, 1986, 1989, 1991 (Festival), 2011, 2012, 2013, 2016, 2017, 2020, 2023 (Anniversary)

William Gillies (1898-1973)

42. Valley with Stream, 1957 watercolour and pencil on paper, 25.5 x 35.5 cm signed and dated lower right, titled verso

PROVENANCE

The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, c.1958

Gillies divided his energy between oil and watercolour; painting in oils was his studio routine, whilst he was happiest working in front of the landscape on his watercolour block, where our two works will have been painted. When filmed in 1970, he spoke eloquently about his watercolour practice:

My landscape painting began with watercolour and a great part of my work has continued in this medium and I feel the peculiar qualities of the medium have had a strong influence on my conception of landscape... I have perhaps opened many people’s eyes to some unexpected, some subtle beauties in our daily surroundings. This has been, I hope, a by-product of my own enjoyment of what I perceive and my great delight in the very act of handling the paint. William Gillies

Both Tweed and Valley with Stream feature watercourses, which Gillies uses as compositional devices, ribboning through the upland hill farms. The bare trees and fields suggest the paintings were created in early autumn, following the season's first storms. These works, which were both painted in 1957, showcase Gillies's key attributes as a painter: spontaneity, originality of line, and his remarkable ability to capture and share his deep love for the landscape before him.

William Gillies (1898-1973)

43. Tweed, 1957

watercolour and pencil on paper, 25 x 35 cm signed and dated lower right

PROVENANCE

The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1958

Tweed

William Gillies (1898-1973)

44. Near Stobo, Peebleshire, c.1950 pencil and ink wash on paper, 25 x 57 cm signed lower right

EXHIBITED

William Gillies Retrospective, Scottish Arts Council, 1970, cat. 108

William Gillies (1898-1973)

45. Boats and Nets, 1955 pencil on paper, 25 x 35 cm signed and dated lower right

EXHIBITED

The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh

John Houston (1930-2008)

John Houston was brought up in Buckhaven in Fife, where the ever-changing light over the Forth estuary and fields falling away to the shoreline were the backdrop to an idyllic childhood of horse fairs, golf and football. The landscape eventually inspired him to become a painter. Houston was drawn into the fold of Edinburgh College of Art and became as prodigious and natural a painter as his mentor William Gillies. He travelled widely, making exhibitions after trips to Europe, Japan and America, always with his fellow artist, wife and soul-mate Elizabeth Blackadder. He was an expressionist who could evoke the subtle, particular character of place, but his vision and ambition always looked outward. John Houston was represented by The Scottish Gallery from the late 1950s. He was ten times a solo exhibitor at The Edinburgh International Festival, between 1961 and his last show in 2008. Houston was honoured with a major retrospective at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in 2005. His work is held in numerous public collections.

The Scottish Gallery exhibitions: 1960, 1962 (Festival), 1965, 1967 (Festival), 1971 (Festival), 1975, 1980, 1990, 1993, 1997, 2003 (Festival), 2007 (Festival), 2009 (Memorial), 2012, 2013

The Forth

Like any great landscape painter there was a particular, deep engagement with one subject and Houston studied the Forth in all conditions with oil, watercolour, pastel and monotype. He

could not recall when he started to paint the views north, from the south of the river, from the beaches of East Lothian to the Paps of Fife or in wild or obscure weather when the view is often anchored by the hard profile of the Bass Rock.

Houston chooses to portray the extremities of the day at the extremities of the land. His theme is the bizarre chemistry of elemental conflict: a snowstorm at sea; the setting sun sinking apparently into the ocean with an almost audible hiss.

Iain Gale for Scotland on Sunday, 10.8.1997.

John Houston, c.1981 Photograph: Robert Mabon

John Houston (1930-2008)

46. Path to the Sea, Evening, 1978 oil on canvas, 20.5 x 25.5 cm signed lower right; signed, titled and dated verso

John Houston (1930-2008)

47. Evening Sea, Gullane Bay, 1985 oil on board, 30.5 x 35.5 cm signed lower left; signed, titled and dated verso

A strong case can be made for John Houston being the greatest expressionist painter Scotland has ever produced. His tireless work ethic, control of technique, on the edge, and sense of the emotional power of colour, exercised over sixty years is an unparalleled contribution. His native Fife was a constant wellspring. It is there on the horizon in much of his work created in East Lothian, and he returned to the landscapes he had walked as a boy throughout his life. The summer fields, hedgerows, birds often rising; the fall of land towards the estuary; the skies lava hot at sunset, but ever changing. This is in his mind’s eye, his passionate place. His colour is never crude and is based in experience but is pushed, like in the work of the Germans he admired: Nolde and Kirchner. Houston worked in all scales, which was a significant professional attribute, each scale of picture giving different challenges. Sometimes there is a struggle towards resolution, his impasto worked over. Other times a painting might be finished in one creative frenzy, and may be left. Sunset Kilconquhar seems one such, so that the moment near sunset is made permanent, each mark telling, each choice of a colour a note in the crescendo delivering a strong emotional punch.

John Houston (1930-2008)

48. Sunset Kilconquhar, 1970-71 oil on canvas, 49.5 x 49.5 cm signed lower left

William MacTaggart (1903-1981)

Born in Loanhead, near Edinburgh, Sir William MacTaggart was the grandson of the landscape painter William McTaggart (1835–1910). He studied at Edinburgh College of Art from 1918 to 1921, at the same time as William Gillies, and travelled to Paris after graduating. He was a founder member of the 1922 Group and in 1927, he joined the exclusive Society of Eight whose members included Colourists F.C.B. Cadell and S.J. Peploe and began, ahead of his contemporaries a successful exhibition career at The Scottish Gallery from 1929. A sumptuous painter in oils, he was instinctively an expressionist and romantic painter. His outlook shifted dramatically after visiting the Edvard Munch exhibition at the Scottish Society of Artists in 1931 (he eventually married the Norwegian curator, Fanny Aavatsmark) and again after studying Rouault in Paris in the 1950s.

From his home and studio in Edinburgh’s Drummond Place in the New Town, some of his best-known works offer a still life, framed by a window, looking east towards Bellevue Church. MacTaggart was president of the RSA from 1959–1969 and was knighted for his

services to art in 1962. From 1951, MacTaggart and his wife travelled the short distance to the Johnstounburn Hotel at Humbie for the Christmas Holidays. East Lothian and the Borders became a favourite landscape and the inspiration for some of his most engaging work, including Glimpse of the Lammermuirs, Dirleton and Humbie, East Lothian.

The Scottish Gallery exhibitions: 1929, 1953, 1959 (Festival), 1966 (Festival)

William MacTaggart (1903-1981)

49. Glimpse of the Lammermuirs, c.1965 oil on board, 24 x 34 cm signed lower right

EXHIBITED

Festival Exhibition, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1966, cat. 37

Sir William MacTaggart in his Edinburgh studio, c.1963

50. Humbie, East Lothian, c.1960 watercolour, ink and chalk on paper, 47 x 62 cm signed lower right

EXHIBITED

Stone Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1960

William MacTaggart (1903-1981)

William MacTaggart (1903-1981)

51. Dirleton, c.1958 watercolour and ink on paper, 28 x 41 cm signed lower left

EXHIBITED Stone Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, c.1960, cat. 35

David McClure (1926-1998)

McClure was one of a group of highly regarded young painters that included James Cumming, William Baillie, John Houston, Elizabeth Blackadder and David Michie all of whom graduated from Edinburgh College of Art in the early 1950s. Their formative years benefited from the examples of a remarkable concentration of talent in the capital, both on the Art College staff and in the annual exhibitions of the RSA, RSW, SSA or SSWA. In addition, The Scottish Gallery was regularly showing established artists such as Anne Redpath, William Gillies, William MacTaggart, as well as younger artists like Joan Eardley and Robin Philipson. McClure and many of his Edinburgh College peers soon joined them. McClure had his first one-man show with The Scottish Gallery in 1957 and the following decade saw regular exhibitions of his work. He was included in the important surveys of contemporary Scottish art which began to define the Edinburgh School throughout the 1960s and culminated in his Edinburgh Festival show at The Gallery in 1969. But he was, even by 1957 (after a year’s painting in Florence and Sicily) at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art in Dundee, alongside his great friend Alberto Morrocco, applying the rigour and inspiration that made the college such a bastion of painting.

Robin McClure (1955-2022) Former Director of The Scottish Gallery

The Scottish Gallery exhibitions: 1957, 1962, 1966, 1969 (Festival), 1989, 1992, 1994, 1996 (70th Birthday Exhibition), 2000 (Memorial), 2003, 2010, 2014, 2015, 2019, 2022

In many of his later still life compositions, McClure plays visual games with the 'painting within a painting' genre, a technique also employed by his Edinburgh School contemporary Robin Philipson and others. In Green Marble and White Jug, there is a classic tipped tabletop still life, another genre typified by Redpath and Gillies, where the still life objects are arranged and shown as if viewed from an elevated angle. It’s a visual illusion of a still life painting, sitting on an easel and where the perspective is skewed, and the deep outlined shadows of the painting offer a three dimensional view. Is it a picture of a painting on an easel or of objects on a tabletop? McClure creates further confusion by mischievously allowing details to escape out over the edge of the suggested canvas on the easel and into the painting’s 'real space'.

Green Marble and White Jug

David McClure, 1981. Photograph: Robert Mabon

David McClure (1926-1998)

52. Green Marble and White Jug, 1966 oil on canvas, 51 x 76 cm signed and dated lower left; signed and titled verso

James Morrison (1931-2020)

Under a Northern Sky

James Morrison was a great painter and a huge part of The Scottish Gallery for more than sixty years. Born in Glasgow in 1932, Morrison studied at Glasgow School of Art from 1950 to 1954. After a brief spell in Catterline in the early 1960s, Morrison settled in Montrose in 1965, joining the staff of Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art in Dundee the same year. From 1987 he was painting full-time. Whole-heartedly a landscape painter, his main working areas were the lush, highly managed farmland around his home in Angus and the rugged wildness of west coast Assynt.

James Morrison held over twenty-five solo exhibitions with The Gallery, which also organised several one man shows elsewhere in the UK and internationally.

The Salmon Bothy

The Salmon Bothy, St Cyrus was painted the year after Morrison had moved from Catterline to Montrose in 1965. Since arriving in the northeast from Glasgow, Morrison had been drawn to paint aspects of the local fishing community provided ample subject matter for the artist, the salmon season operating between February and August of each year. In this painting, the Bothy is painted as a portrait, an anchor building for the fishermen, sitting centrally as the subject, painted under an opaque sky and foreground and the building and surrounding drying nets harnessing the landscape. There is a pale blue horizon line to the right, indicating the sea beyond.

James Morrison (1931-2020)

53. The Salmon Bothy, St Cyrus, 1966 oil on canvas, 90 x 150 cm signed and dated lower right

James Morrison painting in Angus, 1981 photograph: Robert Mabon

Snowstorms over the Grampians, Montrose Basin would have been painted out of doors, not too far from home. This has been painted using the fast medium of gouache and watercolour. Morrison developed a particular technique which required immense skill and sureness of vision – this allowed him to record with speed, his medium allowing a wide range of brushmarks to express and record what was happening directly in front of him - the smooth calm of still water, the gathering clouds, the wide stretch of the Grampian landscape beyond which is about to be immersed under a blanket of snow.

James Morrison (1931-2020)

54. Snowstorm over the Grampians, Montrose Basin, 1974 gouache and watercolour on paper, 53 x 103 cm signed and dated lower centre

EXHIBITED

Under a Northern Sky, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 2024, cat. 15; Festival Exhibition, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1999

There is a moment when you pause on your walk in the country so that even the noise of your own progress cannot impinge on what you see. It is that moment that James Morrison consistently captures in his landscapes. There may be big weather rolling in, snow in the air, or brilliant blue sky, festooned high up with vapour trails. There may be a furrowed field drawing the eye to a hedgerow before a stand of trees, a windbreak for a comfortable arrangement of farm buildings. The artist understands that still, quiet moment of contemplation; it may engender awe; or a sense that all is right and has ever been so, in the rich farming landscape of Angus. His paintings are of real places and if pressed he might supply a map reference for where he set up his easel. But he will find his subjects where others might pass on.