12 minute read

The Models

Jeannie Blyth

The figure was his most significant early subject, and from 1896, for over a decade, Jeannie Blyth was Peploe’s favourite model. She was born around 1883, so was perhaps fifteen when they met. She was a direct descendant of Charles Faa Blythe, the last King of the Gypsies who died at Kirk Yetholm in the Scottish Borders in 1902. Her family had a flower stall at the west end of Princes Street, close to the Albert Building on Shandwick Place where Peploe had his first studio. She was a natural sitter, responding to suggested poses with the inhibition of youth. Smiling Girl (p.39) is supposed to be the first painting he sold, to another painter, Gypsy, c.1896 Alexander Fraser and she is posed with both hands on oil on canvas her left hip, smiling with open mouth over the shoulder Private collection where her loose hair tumbles over the puffed sleeves of her coral blouse. Gypsy of the same time is another character study, another difficult subject as the painter captures the insouciance of youthful confidence. She poses with her hair tied back, but unruly, her colour is high and her blouse off the shoulder, as if she had been dancing. Kirkcaldy Museum holds a pastel drawing of her in a dance pose and we can imagine that Peploe has allowed her to dance as he drew, expressing her exuberance.

Jeannie continued to pose and a few years later she is captured in a unique painting currently titled Gypsy in a Landscape (cat.3); it may well be the picture titled Gypsy Queen, purchased by The Scottish Gallery in 1898. Portrait of Jeannie Blyth, c.1900 The portrait was gifted to Jeannie by S. J. Peploe as a wedding present in 1901. Its whereabouts today are unknown.

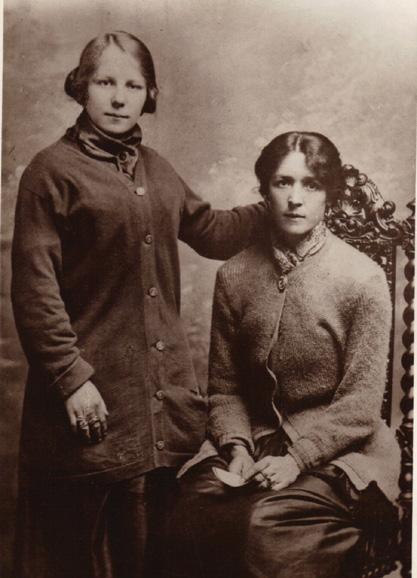

Portrait of Jeannie (p.43) comes from c.1903 when Peploe was in the Devon Place studio and again makes character the subject of the portrait. The look once more is full of attitude, the head at an angle, the glance downwards; Jeannie may be holding a dance pose with her hands on her hips. The ivory flesh tones of her face and long neck are freely painted, the likeness effortless as Peploe works alla prima, the whole portrait likely taking no more than a morning. The family did not approve of her continuing to pose for Peploe after her marriage but at least one significant work was made nearer 1905: The Green Blouse, held by the National Galleries of Scotland. Jeannie had married in the early years of the 20th century and we know from the memoire and research of Linda Lennan, her great-granddaughter, that life was hard. As we can see from the photograph opposite (lower left) she had numerous family and a hard working life; she died in 1938.

Above: Jeannie Blyth with her niece, Maggie Left: Jeannie with her husband and family, c.1930

The Smiling Girl, c.1896 oil on board, 59 x 41 cm signed upper left

Exhibited: S. J. Peploe Memorial Exhibition, Aitken Dott & Son, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1936, cat. 39; S. J. Peploe Memorial Exhibition, McLellan Galleries, Glasgow, 1937, cat.28

Provenance: Private collection, Edinburgh

When A. J. McNeill Reid wrote to Mrs Fraser, thanking her for the loan of Smiling Girl to the Memorial Show which took place at the McLellan Galleries in Glasgow in 1937, he reminded her that this work was the first sold by the artist, from the RSA Annual Exhibition in 1896, thus heralding a long, successful exhibiting career. The painting remained in the collection of Alexander Fraser and by descent was lent to the ACGB, Scottish Committee show curated by Denis Peploe in 1953. After this it disappeared, known only by black and white illustration. Guy Peploe was therefore delighted when the family contacted him in response to the build up to the Peploe 150th exhibition and made it available for loan. A pastel drawing of Jeannie Blyth (below) in the same pose is known, but she pouts, the smile gone. This variety is a clear demonstration that artist and model worked together; it is perhaps surprising that the smile is in oils, a much ‘slower’ medium with which to capture the spontaneity of a smile – an expression quite impossible to maintain. A sunny disposition and the bloom of youth is brilliantly captured by an artist already setting himself the sort of painterly challenges which will characterise his lifelong approach.

Jeannie Blyth, c.1896 pastel on paper Private collection

3. Gypsy in a Landscape, c.1898 oil on canvas, 56 x 51 cm signed lower right

Provenance: Ian MacNicol, Glasgow; Private collection, London Illustrated: S. J. Peploe by Guy Peploe, Lund Humphries, 2012, pl.30

Jeannie engages the viewer directly in a classical, three-quarters pose, draped in a heavy cloak, clasped protectively together below her breast, her red blouse underneath. Behind is an extensive landscape with fields and a hillside. The setting adds narrative possibility to the interpretation, the gypsy as eternal traveller, unconstrained by roots. It is tempting also to speculate that Peploe’s avowed admiration for Thomas Hardy has found expression in a poignant evoking of rural poverty and the risks and sacrifice of pregnancy.

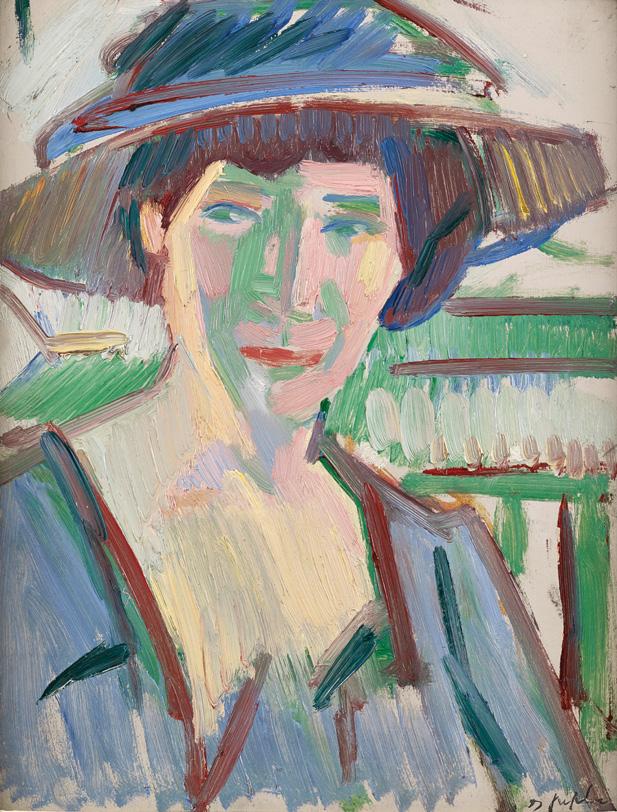

Portrait of Jeannie, c.1903 oil on canvas, 51 x 51 cm signed lower right

Provenance: Private collection

This bust portrait of Jeannie is dated around 1903–4. She has gained a maturity and hauteur in the years since Smiling Girl and Gypsy. The pose is, as often, active: she turns her head and tilts it back so that her look is ‘down her nose’. If her hands were above her head, we would be looking at a flamenco pose, the hair tossed as the head moves from side to side to the rhythm of the castanets. The creamy skin of her neck and shoulders is the tonal highlight and her face is pink at the cheekbones and lips a natural coral red.

Peggy Macrae

The paintings of Peggy Macrae made in the Raeburn Studio from 1907–1909 are remarkable for their technical achievements as well as the evocation of character and suggested narrative. They are consummately elegant works, anchored in La Belle Epoque, inspired in large part by the model herself who worked with the painter on the pose and setting. There are many drawings and some head studies in oil, and a few large scale compositions. The White Dress (cat. 4) is painted with quite extraordinary freedom: long, fluid brushstrokes and shorter impressionist touches are combined; light illuminates and dissolves form. It is the differences that dominate in paintings of the same subject painted within a year or two of each other. This comes without doubt in part from the model whose ability to suggest character is within a suggested narrative: one at a bar, another after the ball the third an elusive presence of beauty in an undefined interior. Peploe, a brilliant draughtsman with conté crayon or brush, deliberately subverts conventional description, instead painting instinctively with broad marks, modelling in light and revealing character rather than building layers of reality. The subject and the elegance of the poses group these works with the portraiture of Whistler, Sargent or even the French society painter Giovanni Boldini, but technically they are closer to the distortions employed by Derain, Matisse and Picasso. These works would be criticised by some as moving towards the crude or even ugly.

The White Dress is perhaps the earliest of several large, ambitious paintings. Peggy is seated in an undefined interior space described in a delicious, elusive palette of grey, mauve, green and white enlivened by swift, broad marks in light tones. Her face is upturned, the cheekbones accentuated, her look serene. She wears a fascinator with a pink rose, and the pink is intensified in her lips and cooler in the flesh tones of her exposed shoulder. The dress flows, is it a wedding dress? Its shape delineated with passages of lilac, blue, purple and a green – a signature colour which will be seen in the modernist work to follow. The artist uses a rounded, hog-hair brush and sweeps the paint onto the canvas in long gestures, some more than two feet in length. His athletic, active painting, moving back and forward to the easel from a vantage some yards back to consider and then dancing forward on the balls of his feet to make his mark. He works alla prima – the delicacy of the painted surface will bear no revision or scraping out, and the whole will have been finished in perhaps two sittings.

Peploe himself recognised the brilliance of these works, which were shown in his 1909 exhibition at The Scottish Gallery, as having no parallel in British painting; but he saw them as at the limit of impressionism. His way forward would be another change of studio, in a new city: Paris.

4. The White Dress, c.1908 oil on canvas, 102 x 76 cm signed lower right

4. The White Dress, c.1908 oil on canvas, 102 x 76 cm signed lower right

Exhibited: S. J. Peploe Memorial Exhibition, Aitken Dott & Son, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1936, cat. 60 (possibly as The Girl in White); S. J. Peploe, Reid & Lefevre, London, 1948, cat. 1; S. J. Peploe, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, 1985, cat. 44 (as The White Lady); The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 2005

Provenance: Private collection, Edinburgh

Margaret Mackay – Mrs Peploe

Peploe first visited Barra with his brother on the yacht Nell, commissioned by the painter Robert Cowan Robertson (1863–1910) from yacht designer George Watson, and launched at Greenock in 1887. The painters stayed on the Atlantic side of the island at Borve but Peploe met Margaret Mackay in Castlebay where she was working in the Post Office. The story goes that with the island predominantly Catholic, the Post Office had to recruit Margaret from Loch Boisdale in South Uist – the predominantly Protestant island to the north. She came from a large family with siblings and halfsiblings. One cousin found notoriety as the determined Excise Officer pursuing the islanders who took whisky from the wreck of SS Politician after its wreck on Eriskay in 1941. Margaret was a beautiful, serene young woman of nineteen with long black hair, a fine carriage and a serenity in presence which was reflected in her character. After correspondence she sought a transfer to the Post Office in Frederick Street in Edinburgh, and took lodgings in Marchmont. They did not marry until 1910 when she fell pregnant. But for these years she was his muse and inspiration and the paintings he made of her speak of love and a deep connection. He found her as a calm, serene, untroubled being: the perfect foil to his own personality, wracked with doubts. He wrote later of his marriage as a kind of liberation derived by accepting the ‘chains of marriage’ and their union was deeply happy and fulfilled. After his death she was the guardian of his reputation, cooperating with The Scottish Gallery and Reid & Lefevre over several exhibitions, as well as with Stanley Cursiter as her husband’s first biographer and Director of the National Galleries of Scotland. She died in Edinburgh in 1959, shortly after the birth of her grandchild Lucy, born to Denis and Elizabeth Peploe.

Peploe drew her often and made paintings throughout their lives together. The earliest known work (shown opposite) is on panel and seems to seek to capture her independence and character: she is after all living an independent life, with a career in one of the few organisations which allowed women this opportunity in late Victorian and Edwardian Britain, even boasting its own Association of Post Office Woman Clerks founded in 1901. She is, as often, in a hat and wears a sensible brown coat, a yellow flower in her button-hole. Ten or so years later he painted her in a large format seated, completely at ease in a dark interior, her arm stretched across the back of the sofa on which she sits. Guy Peploe commented in his biography on the portraits of this period. ‘The very best combine the bravura performance of painting with an emotional commitment which brings out the character of the sitter. This is most apparent, not surprisingly, in a portrait of Margaret of c.1905 which speaks of mutual love in the steady, direct engagement of the eyes and complete relaxation of the pose.’

The right-hand portrait Mrs Peploe hangs in the recently refurbished Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museum.

Margaret, c.1905 oil on panel Private collection Mrs Peploe, c.1907 oil on canvas, 61 x 50.9 cm signed lower right Image courtesy Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums Collection

Mrs Peploe, c.1911 oil on board, 35.5 x 27.3 cm signed lower right

Exhibited: S. J. Peploe, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2012

Illustrated: S. J. Peploe by Guy Peploe, Lund Humphries, 2012, pl.88; S. J. Peploe, National Galleries of Scotland, 2012, pl.54

In 1985 the SNGMA reopened in its new home at Watson’s College, having removed from Inverleith House in the Botanic Gardens: an event worthy of a Royal guest to officiate. The opening exhibition was an S. J. Peploe retrospective, curated by Guy Peploe. His first job was to conduct HRH The Queen around the show. They paused in front of Mrs Peploe and Guy explained that it was a Modernist love portrait made in Royan around the time of the birth of their first child, Willy. He explained the green flesh tones, recalling a Matisse of his wife called The Green Line. HRH paused before asking rhetorically “I wonder what your grandmother thought of having a green face…”