22 minute read

Interview with Frau Gutman

Questions

with Frau Gutman

Advertisement

For this edition of Scribble, co-editor Lily Harding interviewed Frau Gutman about her Zeitgeist project in school. This extra-curricular club has been running successfully for over a year and attracts a diverse membership; it has also been one of the highlights of the recent lockdowns.

Zeitgeist is defined as meaning ‘the spirit of the age’ and encompasses ideas which reveal spiritual, cultural and moral dimensions of a particular age or time period. The Zeitgeist society has enjoyed ranging over a significant number of time periods, tapping into the ideas and thought of the day. We have chosen to give this edition of ‘Scribble’ over to the concept of Zeitgeist, encouraging contributors to delve into a particular era or writer, exploring what their Zeitgeist reveals.

Q1 What is your favourite English-language book and why? How do you choose? I love “The History of Love,” by Nicole Krauss, “Middlesex” by Jeffrey Eugenides, “Bleak House”, “The Cazalet Chronicles”, “Captain Correlli’s Mandolin”. Help, this rather varied and random list could go on! I seem increasingly drawn to American women writers such as Ann Patchett, Nicole Krauss, Meg Wolitzer, Anne Tyler, Brit Bennett - but then also love the novels of Sarah Moss, Maggie O’Farrell and other British female writers. I think I like books that have a strong storyline, but leave you thinking, laughing or crying. A few years ago I discovered The Hay Festival - I tend to go with my family and parents and I create a timetable of events-so that we all get some of our favourites for children and adults - I tend to mainly choose female writers and have been lucky enough to hear wonderful writers, such as Margaret Atwood, Judith Kerr and Elif Shafak. Having said that, I am reading a William Boyd novel at the moment and I love his novels-they are so varied. I also loved Ian Mcewan’s “Atonement”, despite the fact that Bryony (me) betrays Cecilia (my daughter).

Q2 What is your favourite Foreign-language book and why? I think the greatest novel ever written is the “The Tin Drum” (Die Blechtrommel) by Günter Grass). It literally blows your mind. It is about a boy, Oskar, who decides to stop growing by throwing himself head first in to the cellar, as he does not want to part of the society he sees around him-he lives in Danzig (now Gdansk)and is witnessing the rise of Hitler. The drum of the title is from a shop owned by a Jewish man and he loves to visit this toy shop, until it is destroyed during Kristallnacht. This was also the time my grandfather managed to leave Berlin and saved himself from dying in Sobibor - which was the fate of the rest of his family. It is part magic realism, very funny, extremely disturbing and changes you for ever once you have read it. There are so many unforgettable scenes in the novel, such as Oskar joining a troupe of dwarves performing to Nazi soldiers or Oskar watching a Nazi rally descend in to chaos as he bangs his drum and causes everyone to start waltzing. Grass, a deeply political writer captures the despair of living in a world, in which the Holocaust was allowed to happen. There is a scene after the war, when Germany is re-building and fast becoming an incredibly powerful country economically, in which Oskar visits a Bierkeller, where you get served a beer and an onion on a chopping board-the image is so powerful - the need to chop up an onion to be able to cry in a post-holocaust Germany, in which such horrific atrocities were allowed to happen. He was one of the first writers to deal with the theme of guit in post war Germany.

Q3 Do you prefer to read German or French Literature? I I do not think I can answer that - I like to read books. I have read great French books, great German books, but also books from every corner of the world, such as the Egytian author Naguib Mahfouz , the Columbian author Gabriel Garcia Marquez or the Indian writer Arundhati Roy. That would be a fun game for Zeitgeist a literary tour of the World! I also think there can be a difference in what the purpose of the reading the book is-whether it is reading a book purely for pleasure or reading books to discuss in a university seminar or reading group. I recently read and discussed in a book group the fantastic book, “Girl, Woman, Other” and I think this book has so much to discuss and talk about - so it is a great choice for the new Sixth Form book group. I was lucky to have the most fantastic French teacher when I was at SHS - Miss Appleby - I would like to write to her now if I knew where she lived, to say thank you for both inspiring and enabling me to read a book in another language. We studied a wonderful book called “Elise ou la Vraie Vie” by Claire Etcherelli - it felt so exciting to be reading a book in another language about a young woman discovering herself whilst working in a factory in France.

I also loved studying French realist novels of the 19th century and French Feminist writers at university. However, it was whilst living in Marburg that I really fell in love with reading foreign literature. We were just given the freedom to go to any lectures and seminars taking place that semester at the university. I just went to lectures and seminars all day, every day and it is just opened my mind to so much amazing literature. Since that time I am generally drawn to literature and art from the late 19th century onwards and particularly works from the 20th Century. In my last year at Bristol I acted as the “Good Person of Sezuan” in Brecht’s incredible play, in which the central figure, which I played, has to be a woman, who disguises herself as a man in every other scene and only leaves the stage for about 30 seconds at a time to change costumes - the director and my wonderful tutor at Bristol, who helped me to fall in love with Brecht, decided we had to bring out every word for the audience-so a lot of very patient Sixth Formers from around Bristol had to endure about 4 hours of Brecht, as well as my mother who speaks no German. On the first night I remember the curtain shutting and literally collapsing to the ground with exhaustion ( it does sound very indulgently dramatic - but it is not easy to remember that much German!) The following year, when I asked if I could direct the German Society Play Dr Ken Mills, who had directed the productions for the last 20 years very kindly - and rather amazingly - said yes. My first requirement, when directing Kafka’s “The Trial” (Der Prozess) was to get the whole thing wrapped up in 2 hours. That was an unforgettable experience with a cast of about 40 students, made up of both English students studying German and German students spending a year in England and we took the play on tour to Lancaster Uni for the German, winning the award for best production at the German Drama Awards.

Q4 What role does literature play in the A Level language courses?

When you take a language at A Level you get to study a film and a book or play. For the last couple of years I have taught “The Reader” (Der Vorleser) by Bernard Schlink. However, I have changed this year to the drama “The Visit,” (Der Besuch der Alten Dame) by Friedrich Dürrenmatt and I am absolutely loving and have been blown away by the Year 13’s discussions about this fantastic play.

SO, yes there is some literature, but there is also film, art, sociology, politics, psychology, as well as mastering the language. So there is something for everyone! The best part about the A level is that you get to choose any topic you like for the Individual Research Project, which is the for the spoken part of the exam. So, if you are into literature, you can explore this here, but you can choose anything as long as it relates to the German speaking world. Chosen topics since I have been at SHS have ranged from Punk Culture in West and East Germany, female artists and their representations of womanhood, the rise of Extreme Right politics because of the immigration issues in 2015 in Germany and also post war literature called “Trüümmerliteratur,” which translates as rubble literature, literally capturing the time at the end of the Second World War when Germany lay in rubble and ruin, only a few years before the Economic Miracle of the 50’s.

Q6 If you could go back in time to any literary movement to meet the writers, which would it be?

With all the celebrations of a 100 years of Bauhaus, I think I would go back to live in this design school. Students came here to live and breathe art in the broadest sense-whether it be painting, design textiles, furniture or dance. I would like to have a part in the avant-garde Bauhaus Ballet, go to the wonderful parties get to be creative all day everyday, regardless of whether you were male or female.

Q7 Would you rather be turned into a huge beetle and cope with the ensuing existential crisis, or

take part in the doomed June Rebellion of 1832 with the knowledge that one day your death will be turned into a multi-award-winning musical?

Why do I feel like it would be the beetle? - there is a wonderful moment in Kafka’s exquisite novella, where the beetle just walks upside down across the ceiling-just because he can to get the thrill of falling down on the ground and starting again. I can not see myself as a political leader, so I guess it will have to be the beetle! I think you would be taking part in the Rebellion?

Q8 What is the one book you think everyone should read?

Oh goodness-for children, “When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit, “ by Judith Kerr or “Carrie’s War” by Nina Bawden. Poetry wise it would be either “Serious Concerns” by Wendy Cope - the first book I gave to my husband or The Collected Works of W. B. Yeats as it is so achingly beautiful. I think the book that everyone should read is that first book when you think, I chose this, I want to keep reading it and I want to now read more. It does not matter what that is.

In year 7 at SHS I had the most extraordinary teacher called “Mrs Garnons-Wiliiams.” She gave us each a card to record everything we read that year. I was so sad that she only taught us for one year-but with her I went from reading children’s books to classics such as “Jane Eyre”. She was just so passionate about reading.

Q9 What is on your reading list for this year?

I have so many books that I want to read - I have a large pile of books by my bed -I would like to read “Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche, as I loved “Half of A Yellow Sun”. I also look forward to reading Fleishman is in Trouble and American Dirt. I would also like to re-read “Tender is the Night,” which came up in a Zeitgeist session, when Maddy Chilcott took us time travelling to the roaring 20’s. I have to record all the books that I read on Good Reads otherwise I forget what I have read these days and I like doing the Reading Challenge.

I like reading the longlists of books for the Women’s Prize for Fiction, and sometimes the Booker Prize. I also love Instagram, as you can get so many good recommendations, particularly from America, Germany and France. I try to buy books from Independent’s such as Booka and love the recommendations from Daunt books. However, in my Amazon basket at the moment is “A Town Called Solace” by Mary Lawson, “Rainbow Milk” by Paul Mendez and “Acts of Desperation” by Megan Nolan. Those all came from recommendations from book sellers or writers on Instagram.

Zeitgeist Iggy takes us to Regency England

Maddy took us in costume on our first time travel adventure to the roaring 20’s and led a really fascinating discussion on the culture, politics and social issues of the 1920’s - we also thought about the parallels with living in the 20’s a 100 years on.

zeitgeist;

the spirit of time; the defining mood of a particular period of history as shown by the ideas and beliefs of the time

Q10 Why should people come to Zeitgeist?

Because it is great fun! There are always little gems of new knowledge. Folk are amazing - hearing students and teachers talking about their passions - it plants the seed to find out more - I want t-shirts saying something naff like “blow your mind with culture, creativity and curiosity, because Miss Pardoe found this amazing wooden head sculpture from the 1920’s for our new logo. When I was at school in the Sixth form, I was just desperate to discuss ideas and books. I hate the idea that culture should be seen as something elitist or boring - I never want people to say, “I should read more -” there is no should about it, reading a book is a pleasure and whatever you read is OK. However it is also fun to try and go out of your comfort zone - that is what is so good about a group like Zeitgeist - you get ideas from others.

William Blake The Man and his Zeitgeist

By Mr Robin Aldridge

For a guest Zeitgeist session in the Autumn term, Head of English, Mr Aldridge, delivered a talk on the poet William Blake and his awkward relationship with the world in which he lived and the values it held that Blake so objected to.

William Blake was an English poet and illustrator who lived between 1757 and 1827; he was voted as the 38th greatest Briton of all time in the 2002 ‘Greatest ever Britons poll’ and has developed a cult following since his death. Blake’s works are full of mysticism and visions, maybe because he was such a dreamer and Romantic, but I think also because he was so at odds with the world he found himself living in. Blake was considered mad by contemporaries for hisunique and personalviews, but held in high regard by later critics for his expressiveness and creativity, and for the philosophical and mystical undercurrents within his work – a man out of his time! It is this sense of not belonging to the late c.18th and early c.19th world that makes him a true example of a literary figure who lived his Zeitgeist in a public way – he found huge fault with his contemporary world and his work was often born out of the philosophical and philanthropic pain he felt so sharply as he looked upon many facets of society, including relatively modern topics as sexual identity and liberation and racial inequality.

William Blake was a man of deep faith and religious belief, but who lived in a world which couldn’t match what he believed. He lived through a significant amount of social and cultural upheaval, primarily the Industrial revolution in England (1750-1850), The Enlightenment movement of. C17th and c.18th Europe which sought to de-mystify the human condition by applying fashionable disciplines of Science, logic and rationality, Revolution and violence in Europe – principally the French revolution of 1789-1799, but also the rise and pursuit of the British Empire under King George III (1760-1820) as far afield as the Americas, the Caribbean and Africa. Blake’s works crave a return to a more innocent and wholesome life, where children could be children, where love was the dominant motivating force behind life, and where mankind could live with humility and honesty – a return to the concept of ‘Albion’ which punctuates so many of his poems and illustrations. Blake was living in an England he despised, and his Zeitgeist encouraged him to look back into the past for the blueprints to re-generate and re-align modern life to something he could support; of course, in his lifetime, this was a wholly futile pursuit.

For me, Blake’s pain, suffering and philosophical disquiet can be summarised by five poems, four of which appear in his collection ‘The Songs of Innocence and Experience’, published in 1794. I wholeheartedly recommend this collection for any Blake newbie, as it is an entirely accessible collection of poetry which ranges across a wide range of topics and ideas. What is central to the collection is the structure of juxtaposition, allowing Blake to present and question his ideas alongside the life he viewed in eighteenth century London. Half of the collection is ‘The Songs of Innocence’ which has an unfaltering tone of positivity, celebration and joy – life as it should be; the second half is ‘The Songs of Experience’ which, by contrast, voices Blake’s pain and wonder at the priorities he sees in his modern world, where ‘experience’ - knowledge, learning, self-conscious thought – has replaced the innocence, and, in his view, destroyed the fundamentals of the human condition and of human identity.

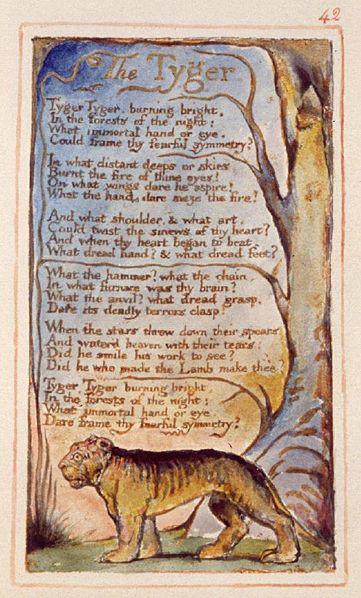

A great example of this comes in the pair of poems ‘The Lamb’ and ‘The Tyger’. In the former, Blake celebrates the existence of a lamb, extolling its simple life and virtues. The poem is very child-like and lacks the artful complexity of its partner poem in experience, but has a very clear message: we are all God’s creations and should not have the arrogance to perceive that we are in any way powerful or self-governing. The image of the lamb with ‘clothing of delight / softest clothing, woolly, bright’ is underpinned with the lamb’s ‘tender voice / making all the vales rejoice’, but is arguably an image used as a means of asking questions about the whole of creation. Blake repeats ‘little lamb who made thee? Dost thou know who made thee?’, musing on how life is created on earth; he concludes, ‘he is called by the name / For He calls himself a Lamb’ asserting that God is the only creator of life and that mankind, created in Imago Dei, are all representations of God’s benevolence and all-encompassing love. For Blake, however, this rural idyll was quickly and significantly being shattered by the Industrial Revolution, factories springing up overnight, creating slums, poverty, a working class and extreme wealth and privilege in double-quick time. Blake explores this in the poem ‘The Tyger’, a masterclass in extended metaphor, but also the voice to the deeply unsettling thoughts he had whilst the world around him changed irrevocably. Centrally, it asks a question about creation: how can we understand a God who is capable of creating the innocence of the lamb and the fury of the tiger? However, it is far more complex than that, because at the same time Blake is suggesting an equivalence between divine creation and mankind’s pursuit of manufacture and power of the creative process. The poem is redolent with industrial imagery – ‘burning bright’, ‘what the hammer? What the chain? / In what furnace was thy brain? / What the anvil?’, pointing towards Blake’s disquietude with the industrial processes he witnessed driving the country, at

the expense of the idyllic, pastoral Albion he prized so much. The poem concludes with a deeply philosophical, but ultimately unsettling, question – ‘Did he smile his work to see? / Did he who made the Lamb make thee?’. Blake’s Zeitgeist is summarised in this pair of lines for me – if God is the creator of everything, then how can this omnibenevolent being create such beauty and joy, and at the same time create pain, suffering, destruction and a being designed exclusively to prey and maim?

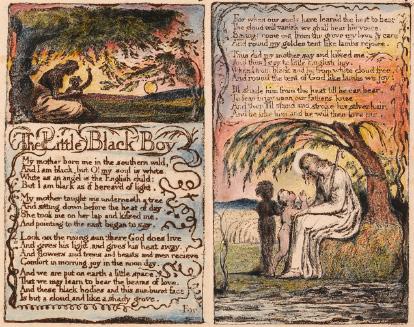

Two further poems in the collection stand out to me as Blake questioning and reconsidering the world in which he lived – the presentation of Empire in ‘London’ and an extension of this when he tackles the slave trade in ‘Little Black Boy’. In the late c.18th, the British pursuit of Empire was all-consuming under King George III who used the might of his army and navy to travel across the world and claim lands for his Empire, in a bid to make his Empire larger and more powerful than other Empire nations, including France, Spain and Holland. In ‘London’, Blake walks round the capital city at night, and is largely disgusted by what he sees and hears, representative not of a nation of great power and wealth, but a nation that is diseased and corrupt. In this poem, the moral ruin of the country is firmly placed with two powerful institutions – the monarchy and the church. Blake points to ‘how the chimney sweeper’s cry / every blackening church appals’, suggestive of the church’s lack of moral care towards the poor of London, in particular the orphans who so often were sold as chimney sweeps, whilst building churches based on huge ostentation and bling; this idea is also explored in the two poems entitled Holy Thursday, where Blake vehemently criticises the immorality of celebrating the giving of alms by the Church once a year, by association suggesting the church’s absence for the remaining 364 days in the calendar. Back to ‘London’, however, and the monarchy is presented as equally immoral, in the image ‘the hapless soldier’s sigh runs in blood down palace walls’; the price of Empire then, according to Blake, is the blood he perceives as being on the hands of the King – the deaths of all those soldiers and sailors who died in pursuit and defence of the British Empire. The element of Zeitgeist that pervades this poem is rich for me – Blake, a proud and patriotic Englishman just simply cannot accept the dereliction of responsibility he sees in the nation’s foundation institutions; his is an Empire he cannot morally celebrate along with the rest of the nation.

Maybe the poem which places Blake at greatest odds with his time is ‘The Little Black Boy’, a poem which is so forward-thinking and c.21st relevant that it becomes striking in its simplicity of message. The poem revolves around two children in conversation – one white and one black – but children who symbolise White Empire and the enslaved natives of Empire nations. The critic David Punter points out that ‘while all the early parts of the poem might seem to suggest that the black boy acts upon his presumed subservience to white ideals, the conclusion magnificently undercuts that, suggesting that the black boy has his place in the grand scheme of things’ and actually is morally superior to his white peer. The poem opens in the voice of the black child, asserting that ‘My mother bore me in the southern wild…I am

black as if bereaved of light’ and although this is a poem Blake located in the Book of Innocence, the black boy is given significant wisdom by the poet. The child goes on to state ‘we are put on earth a little space / that we may learn to bear the beams of love’, arguing essentially that mankind’s sole duty it to learn to love and be loved by God, and that they will be rewarded: ‘when our souls have learned the heat to bear, / the cloud will vanish; we shall hear His voice’. The black child is used a cipher for all of those enslaved by the white man, but his voice is one of hope for racial equality and social justice, at a time when these concepts were not even a consideration in Blake’s world – anti-slavery debates were very new in c.18th England and once again Blake finds his thinking disconnected from popular thought. The black boy reaches the conclusion that ‘when I from black and he from white cloud free…I’ll shade him from the heat, til he can bear / to lean in joy…’, positioning himself in the role of teacher and support for the white child to become aware of the errors of his colonial privilege, in a time when white and black ‘clouds’ have become irrelevant. Fast-forward to 2021 and the world in which we live, and I think Blake would be appalled that the black boy is still waiting for his white counterpart to truly appreciate just how unjust racism is and to act upon this knowledge for the good of humanity.

The final poem worth mentioning is ‘Jerusalem’, which has become England’s unofficial national anthem and is often sung at national events. The is Blake’s ‘therapy’ poem in which he tries to offer himself solutions to what he finds so offensive and problematic about his own lifetime. In the middle of the poem he muses, ‘was Jerusalem builded here / among these dark Satanic mills?’, echoing his inability to balance what he sees with what he believes (in The Lamb and The Tyger), but then progresses to a rallying call to his followers, both in his lifetime and in the future. The imagery of conflict in the third stanza is obvious – ‘bring me my bow…/bring me my arrows…/bring me my spear…bring me my chariot of fire’ and here Blake is appealing to all writers, thinkers, academics, visionaries and prophets that will follow him across the centuries – use your weapons (words) to work towards a better world and allow people to see what needs to be seen. The final stanza is a powerful one, and effectively Blake’s own mantra; ‘I will not cease from mental fight, / Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand, / Till we have built Jerusalem / In England’s green and pleasant land’. Far from giving up on his country, Blake wants to rebuild it with all of the priorities re-aligned and encourages everyone that follows him to continue in this fight.

Zeitgeist’s concept of embodying the spirit of the age is alive and well in all of Blake’s works; I firmly believe that very little of what he wrote would have not been possible should he have been at peace with his times.