SPRING/SUMMER 2024

SPRING/SUMMER 2024

IDEALISTIC IN SPITE OF MYSELF

INTERVIEW BY CHARLES NEWELL

MICHAEL ARDEN

LAUREN YALANGO-GRANT + CHRISTOPHER CREE GRANT

OFFICERS

Evan Yionoulis PRESIDENT

Michael John Garcés EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT

Ruben Santiago-Hudson FIRST VICE PRESIDENT

Dan Knechtges TREASURER

Melia Bensussen SECRETARY

Joseph Haj

SECOND VICE PRESIDENT

Joshua Bergasse THIRD VICE PRESIDENT

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Laura Penn

HONORARY ADVISORY COMMITTEE

Karen Azenberg

Pamela Berlin

Julianne Boyd

Graciela Daniele

Pam MacKinnon

Emily Mann

Marshall W. Mason

Ted Pappas

Susan H. Schulman

Oz Scott

Dan Sullivan

Victoria Traube

MEMBERS OF BOARD

Saheem Ali

Christopher Ashley

Jo Bonney

Shelley Butler

Donald Byrd

Rachel Chavkin

Desdemona Chiang

Valerie Curtis-Newton

Liz Diamond

Byron Easley

Justin Emeka

Lydia Fort

Leah C. Gardiner

Christopher Gattelli

Kathleen Marshall

Michael Mayer

Robert O’Hara

Annie-B Parson

Lisa Portes

Lonny Price

Jon Lawrence Rivera

Bartlett Sher

Katie Spelman

Susan Stroman

Maria Torres

Tamilla Woodard

Annie Yee

SDC JOURNAL

EDITOR

Stephanie Coen

MANAGING EDITOR

Kate Chisholm

COLUMNS EDITOR

Lucy Gram

GRAPHIC DESIGNER

Adam Hitt

EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE

Melia Bensussen

Joshua Bergasse

Terry Berliner

Noah Brody

Liz Diamond

Justin Emeka

Sheldon Epps

Lydia Fort

Annie-B Parson

Ann M. Shanahan

Seema Sueko

Annie Yee

SDC JOURNAL PEER-REVIEWED

SECTION EDITORIAL BOARD

SDCJ-PRS CO-EDITORS

Emily A. Rollie

Ann M. Shanahan

SDCJ-PRS BOOK REVIEW EDITOR

Kathleen M. McGeever

SDCJ-PRS ASSOCIATE BOOK REVIEW EDITOR

Ruth Pe Palileo

SDCJ-PRS SENIOR ADVISORY COMMITTEE

Anne Bogart

Joan Herrington

James Peck

SPRING/SUMMER 2024 CONTRIBUTORS

JoAnne Akalaitis

Leraldo Anzaldua

Michael Arden

Heather Arnson

Dani Barlow

Melia Bensussen

Terry Berliner

Liz Diamond

Justin Emeka

Pascale Florestal

Arnaldo Galban

Christopher Cree Grant

Pam MacKinnon

Mayte Natalio

Charles Newell

M. Bevin O’Gara

Bridget Kathleen O’Leary

Adesola Osakalumi

Maurice Emmanuel Parent

Annie-B Parson

Lisa Rafferty

KJ Sanchez

Megan Sandberg-Zakian

Ellenore Scott

Dawn M. Simmons

Lauren Yalango-Grant

Annie Yee

SPRING/SUMMER 2024

SDCJ-PRS CONTRIBUTOR

Michael Osinski

ST. LAWRENCE UNIVERSITY

SDC JOURNAL is published by Stage Directors and Choreographers Society, located at 321 W. 44th Street, Suite 804, New York, NY 10036. ISSN 2576-6899 © 2024 Stage Directors and Choreographers Society. All rights reserved. SDC JOURNAL is a registered trademark of SDC.

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

Letters to the editor may be sent to SDCJournal@SDCweb.org

POSTMASTER

Send address changes to SDC JOURNAL, SDC, 321 W. 44th Street, Suite 804, New York, NY 10036.

ESSAYS BY TERRY BERLINER, JUSTIN EMEKA, ANNIE-B PARSON + ANNIE YEE

PEER-REVIEWED SECTION

SDCJ-PRS BOOK REVIEW

46 Inside the Performance Workshop: A Sourcebook for Rasaboxes and Other Exercises

EDITED BY RACHEL BOWDITCH, PAULA MURRAY COLE + MICHELE MINNICK

REVIEW BY MICHAEL OSINSKI

SDC FOUNDATION

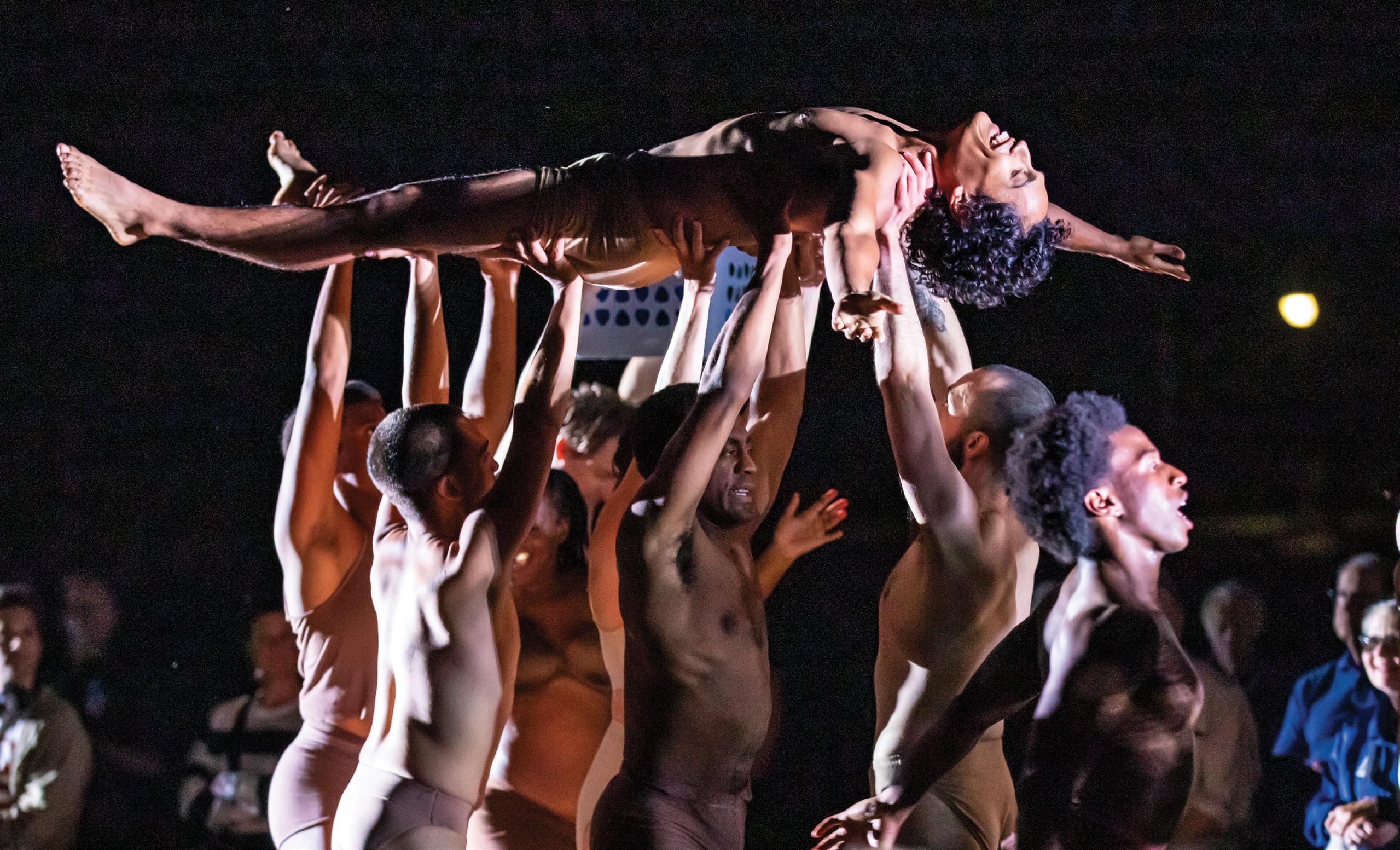

48 The Journey from Dancer to Choreographer

A PANEL DISCUSSION WITH MAYTE NATALIO, ADESOLA OSAKALUMI + ELLENORE SCOTT

MODERATED BY DANI BARLOW

SDC LEGACY

54 HINTON BATTLE

MICHAEL BLAKEMORE

MAURICE HINES

MIKE NUSSBAUM

This year, SDC is celebrating the 65th anniversary of its founding. An anniversary is an opportunity to reflect on where we’ve come from and to imagine where we want to go next, to remember our origin story and commemorate our collective struggles and hard-won triumphs.

On April 24, 1959, Judge Saul Streit, Presiding Justice of the New York Supreme Court, signed the incorporation documents establishing what was then called the Society of Stage Directors and Choreographers (SSDC) as a national independent labor union.

Director Shepard Traube was elected as the first President of the Executive Board, with Agnes de Mille and Hanya Holm as First and Second Vice Presidents, respectively, and Ezra Stone as Secretary.

Those leaders—and the small group of women and men who joined them—founded the Union because they recognized that directors and choreographers were the only group of theatre workers on Broadway whose work lacked Union protections. Their first major battle was to secure recognition as the official collective bargaining unit for Broadway directors and choreographers.

After two failed attempts to negotiate an agreement with the League of New York Theatres, in 1962, the SSDC Executive Board authorized its Members to withhold their services from all first-class productions. It was only when Bob Fosse refused to break this strike pledge when offered a contract to direct and choreograph a production of Little Me that producers recognized the Union, setting the stage for the successful negotiation of the first minimum Broadway contract.

SDC has significantly expanded the size and strength of its Membership and its covered jurisdictions since 1959. Founded with 164 Members, SDC has grown to include more than 3,400 professional directors and choreographers working across the United States. Today, SDC provides vital employment protections, including health and pension benefits, through its many collectively bargained agreements, promulgated agreements, and independent producer agreements. SDC Members file more than 2,500 employment contracts per year, and SDC has expanded its employment jurisdiction to include fight choreographers and Broadway associate/resident directors and choreographers.

Through the years, our core conviction that directors and choreographers are vital to the health and future of American theatre has remained. SDC continues to fight for the recognition and compensation that its Members deserve.

To commemorate our anniversary, we are celebrating the crafts of direction and choreography with a social media campaign called 65 for the 65th. This spring, we sent out a survey to the Membership asking, “Who are the SDC Members whose work as a director or choreographer has most inspired the field or your own artistic path?” Seventy Members responded within the first 24 hours. From these nominations, a task force helped us choose 65 remarkable directors and choreographers to spotlight throughout the year. We are glad to have this opportunity to recognize these artists—our visionary leaders, colleagues, and friends—and to introduce them to those who may not yet know of their impact.

Together, we are custodians of our little piece of the timeline of the Union, entrusted with ensuring that SDC endures and moves ever forward. As the American theatre continues to experience existential challenges, the story of SDC’s founding and the achievements of our Membership over the years remind us that, with strength and solidarity, growth and advancement are possible even amidst uncertainty. We are inspired and heartened by our Membership’s dedication, artistry, and continuing commitment to protect and empower directors and choreographers throughout the field. Thank you, and Happy 65th Anniversary!

In Solidarity,

Evan Yionoulis Executive Board PresidentI’ve been thinking a lot about silence lately. Quiet. This has been brought on, perhaps, by several years now of constant, at times relentless, noise, even as our work—and your work—was paused for much of that time. Of course, there are different kinds of quiet. The calm, the unsettling, the necessary. I would posit that we need a bit of each to be healthy—much like food, activity, and friendship. The quiet that comes with sleep, even with sleeps that are filled with to-do lists and dreams.

Lately, I’ve been drawn to the quiet that opens the space where inspiration dwells, inspirations we need to do our work at the Union in service of what you do. To get to that place, we must first identify the noise, the chatter that distracts even as it appears to inform. It may be shinier, but often this first layer can simply overwhelm without much benefit to anyone. Once we filter out the chatter, we must listen again carefully for the urgent and triage accordingly, committing ourselves to coming back once we have surveyed the full measure of what is out there. Only after, after the distractions have been separated and momentary crisis abated, can we hear differently. This is where noise becomes sound that resonates very differently, and we can begin to feel the quiet. A space where we can begin to consider, to find solutions rather than temporary fixes.

I seek some quiet each day as I move from meeting to meeting, task to task. I am not always successful.

Today, I had time set aside, a quiet space to read through this issue of SDC Journal. Maybe because I have been preoccupied by my own need for quiet, for space, on each page I found a moment or two where you found inspiration, in the quiet, in slow spaces. Members’ reflections of how meaningful the transformation of ideas can be in quiet space.

Michael Arden and his collaborators Lauren Yalango-Grant and Christopher Cree Grant worked together during the pandemic. Lauren and Cree shared the practice of “slow being smooth and smooth being fast” with Michael and he is a convert. As am I. Michael goes on to reflect on what he learned while working with his company, The Forest of Arden, in the midst of the pandemic. “What was it like when we were on a field outside, 20 feet apart, having to communicate?” he wonders. “What was helpful, and what from that experience can we bring into the fast-paced environment of the rehearsal studio? We have to keep reminding ourselves to slow down.”

Pam MacKinnon mentions liminal spaces as she shares her work with set designer Tanya Orellana on the play Big Data “We wanted this liminal, open space.” Isn’t that where we spend much of our time? Certainly, and perhaps if we spent more time there—on the precipice of something new—we might find it. I think you must be quiet; you must pause to know that is where you are. I think you must do this every day in rehearsal halls across the country.

Arnaldo Galban talks about Saheem Ali’s inclusive style of directing, which includes listening to everyone, unabashedly allowing others’ ideas to influence his work, and being humble. KJ Sanchez references writing a book she has titled The Radical Act of Listening. “In it,” KJ says, “I look at some of my favorite listeners and revisit why I fell in love with making theatre based on listening in the first place.”

In the conversation between Melia Bensussen and Liz Diamond, Liz talks about deep listening and acute observation as being central to a director’s process. Combined with Melia’s call for generosity of spirit, I imagine a space where inspiration is in abundance.

And JoAnne Akalaitis, our cover subject—what an amazing reflection she shares on New York in the 1960s, and everything that was important. (“Perhaps most important,” she says, “was acknowledging the importance and presence of children and family in the community of Mabou by including a babysitter in every budget. It was called, for the purposes of accounting and the IRS, ‘rehearsal assistant.’” Imagine?)

In Charles Newell’s interview with JoAnne, she quotes the English playwright Aphra Behn: “Theatre is a place where secret signals are sent to the audience.” These signals can sit in the moments of quiet. The moments that can send that next spark of inspiration to the audience member who will create the next moment, and the next, and the next. As our art form evolves and shifts and so much of what is new has come before, in different iterations, how do we ensure more takes hold? I, and I know all of you, will continue to yearn for the moments of clarity setting themselves apart from the chaos. And if we are lucky, those moments of quiet will transcend their seeming mundanity and transform into something powerful, something beautiful, something of meaning.

In Solidarity,

Laura Penn Executive Director PHOTO HERVÉ HÔTE WITH KJ SANCHEZ

WITH KJ SANCHEZ

Who or what inspired your theatre career?

Way back in 1989, I was an undergraduate student at the University of California, San Diego. Up to that point, my theatre references were very limited. I had been a ballet folklórico dancer and had only been in a few plays—Agatha Christie plays mostly. Anne Bogart was a guest director at UCSD, making a play with the MFA

actors, and I went to see the production as an assignment for one of my classes. It was called Strindberg Sonata and was a collage of all of Strindberg’s plays. It was the very first avant-garde anything I had ever seen. I had no idea what was going on, but I found my body reacting to it; I found myself gasping at one piece of movement, laughing at another, feeling like I might cry at a third. Yet still, my brain was completely flummoxed. I had to go back a second night because my brain needed to figure out why my body liked it so much. Now, so very many years later, I get a lot of my inspiration from my students (I run the Directing MFA at UT Austin), especially when I see them making choices that are speaking to the body, not just the brain.

Where do you get your inspiration? Is it books, movies, visual art?

All over the place. Music: I listen to Bebe’s album Pafuera Telarañas on loop. I watch and re-watch the TV shows The Larry Sanders Show and Our Flag Means Death—long live queer pirates! I get tons of inspiration from the architect Santiago Calatrava—the way he can make my heart soar with scale and line. And book-wise, I’ve been learning a lot from Adrienne Maree Brown’s We Will Not

Cancel Us; Tim Harford’s Messy, which is about how as artists, the things that get in our way can end up being the key to our best work; each and every Miriam Toews book (how does she manage to be so personal, so dark, yet so expansive and so luminescent?); and the one book that I have gotten tons of inspiration from, Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. I first read it when I was in my twenties and I re-read it every few years. It’s a different book every time I read it because I’m different every time I go back. There’s a new translation by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky that blew my mind. They offer so much insight into the undercurrent critique of Stalin’s reign of terror. I can’t wait to see the recent movie adaptation that’s causing a stir in Moscow right now.

You are the Founder and CEO of the theatre company American Records, which makes theatre that chronicles our time. What inspires you about the present moment, and about directing now?

With American Records, it feels like a great time because a lot of our field is catching up to what some of us have been doing for a very long time: making work that says, “We see you, we hear you. You matter.” And I think more and more theatre companies are understanding that community engagement is not about ticket sales but rather about being good citizens of our towns, cities, communities, about being good neighbors.

This is also a hard time. I based 20-plus years of making documentary plays on the notion that everyone has a story to tell. But after the 2016 election, I no longer wanted to hear from a good portion of our country. What is a professional listener supposed to do when she can no longer bear listening? I had a crisis of faith. And little by little I’m crawling out now. I just finished writing a book, The Radical Act of Listening, which will be published by Routledge, and in it I look at some of my favorite listeners and revisit why I fell in love with making theatre based on listening in the first place.

What texts or writers have inspired you from a formal perspective and how do they influence your directing work?

Shakespeare and Octavio Solís. Both writers’ works have structures I never get tired of scaling; both have worlds I never get tired of exploring. The language asks me to approach it like a scientist—I have to know what to lean into, what to throw

PHOTO KRISTI GRIFFITH

away. It’s math, it’s soaring ambition, a huge heart, and lots of fart jokes.

Karen Zacarias, Ken Cerniglia, and I are working on an adaptation of Romeo and Juliet set in Alta California in 1948, after Northern California had gone from being New Spain to Mexico to a brand-new US territory. The Montagues and Capulets are Mexican/Indigenous families and Paris and the Prince are US Calvary. It’s bilingual—Shakespeare wrote the English and Karen wrote the Spanish. Oh, and Romeo is a woman. We can do all of this because Shakespeare gave us formidable text: it holds us up. And as for Octavio Solís, I directed the first four productions of Quixote Nuevo, which I consider one of the best plays ever written. Full stop.

You recently directed José Cruz González’s American Mariachi. Where did you find inspiration for that piece?

American Mariachi is such a lovely event of a play—it invites you into a home and family and a love for mariachi music. When I was a kid, all I wanted to be was a mariachi singer; they were the coolest, sexiest, chicest people I knew. I even took mariachi lessons. So all of us on this production—designers, actors, technicians alike—we just leaned into what we love. And to see the show in front of audiences at the Alley Theatre in Houston: wow. [Artistic Director] Rob Melrose is doing such great work there. To see the house full of Tejanos watching, listening, and singing along to their music. Yum.

What’s a great play or musical you love that you feel people don’t talk about much, or may not have heard of?

Herringbone [book by Tom Cone, music by Skip Kennon, and lyrics by Ellen Fitzhugh], a one-man musical originally performed by Joel Grey. I saw BD Wong perform it at the McCarter. Total. Magic. And it has one of my favorite lines: “In hard times, culture does real well.”

KJ Sanchez is a professional playwright and director. She is the founder and CEO of American Records, a theatre company, and Associate Professor and Area Head of the MFA Playwriting and Directing programs at the University of Texas, Austin.

BY LERALDO ANZALDUA

BY LERALDO ANZALDUA

Motion capture work for video games uses all the experiences I’ve ever had in theatre—as a fight director, actor, and teacher of stage combat.

My first job as lead action director was on the video game The Chronicles of Riddick: Escape from Butcher Bay. I learned that as the action director on a video game, my first job is to put together the character profiles for each character that appears in the game. This means I choose the moves, weapons, or abilities for each

character, and then make sure that the creative team takes those abilities and skills into account during the casting process.

Once we have a team of actors, we assign different roles or different moves and then work on bringing them to life. Unlike theatre or film, video game actors don’t have to “look” like the character they’re playing, but their ability to physicalize and embody the character’s style, motion, and moves is key. We try to find actors with skill sets or vocabulary that may apply to any given character; these are “utility actors” who can play multiple different characters for any given project. We also bring in specialists: martial artists of a particular style, people with experience with different firearms or weapons, gymnasts, or dancers.

As we build the character profiles, we compare the artist renderings and description and identify each character’s qualities and how they move. This can be influenced by things like size, shape, and descriptives, such as if the characters are human, animal-like, robotic, inorganic, etc. We then shape their actions from a menu of qualities we’ve identified: if the characters are fast or slow, if they have abrupt or extended attacks and actions, or if their attacks are linear or organic, for instance. These details help bring life to the characters and help make the moves more accessible to perform and repeat for the actors.

We look through the storyboard and shot lists and create move sets—similar to pieces of blocking and choreography for any given character. “Move sets” are anything a player of a video game can make the character do using their game controller or keyboard: running, walking, sneaking, attacking, etc. We also build “in-game moves,” or lists of reactions and actions for the characters, including how they celebrate, how they fidget when the player has put their controller down, or how they talk.

At this point in the video game development process, I start to draw more on my fight choreography training as we film the scenes. As in a theatrical rehearsal, we film on a set with some practical elements and some elements taped out for the actors. We choreograph the action or block the scenes like a regular narrative scene: entrances, exits, dialogue, and character action.

Much like film, the action in a video game must be fast and precise. Much like theatre, it must be choreographed and assembled. As the action director, it’s my responsibility to make sure that the action, the character work, and the shot lists are sustainable for the performer and take into account the length of time we have to choreograph and record. As with fight direction in theatre, it’s a collaborative process. I talk to the artists, the writers, and the team leads to come up with movement vocabularies that are interesting and creative for the characters and possible for the actors to perform.

Once all this planning is ready, the actors suit up in skintight suits and the team places little reflective dots on all their major joints and muscle groups. We set up shots in varying degrees of need and difficulty. To keep the performers healthy and safe, we make sure safety concerns are addressed: if an actor is falling from a high platform, for instance, we have pads, mats, and the team there to help. We schedule scenes in blocks that take into account the number of performers, complications of each scene and choreography, and level of impact on the performers’ bodies. Ultimately, we all want to build this world in ways that are fun and safe.

We rehearse, and the cameras and computers record everything. Unlike traditional film cameras, motion-capture cameras send out a red or white light that reflects off the dots on the actors’ suits and sends information back to the computers. The computers then create a stick figure of the performers—a wireframe—that computer specialists can then layer any kind of character “skin” over to serve the needs of the project. The work is precise and grueling because the camera doesn’t forgive mistakes, but it is some of the most challengingly beautiful work I do.

Leraldo Anzaldua is Assistant Professor of Movement & Stage Combat at Indiana University Department of Theatre & Dance and a fight director, intimacy director, actor, anime voiceover performer, motion capture/ face caption performer, and action director.

Kate Atwell’s new play Big Data premiered this spring at American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco, home of the tech industry. The play focuses on the power of technology and includes a character called “M”—played in A.C.T.’s production by BD Wong—who is an algorithm. SDC Journal spoke to

director Pam MacKinnon about how she worked with her collaborators to dramatize the impact of technology on the play’s characters and get the audience thinking about their own relationship to tech.

How did your work with Big Data begin?

I directed a world-premiere play of Kate’s in 2019 called Testmatch, at A.C.T., and we commissioned her shortly after that process. She wrote about three plays while trying to get to Big Data, but it really took off when she personified the notion of the algorithm of tech. That’s when the play took a turn toward exciting theatricality.

Kate and I are both interested in playing with theatrical form. Act One is very different from Act Two in this play. In Act One, characters interact with the algorithm character, M, who dictates, elicits, and aids in their choices. M is on stage and present; it is his world, so the set is a stripped-down liminal space. Scenes are short; transitions are many. M is not present in Act Two. And Joe and Didi, the new central characters of this act, do not live with technology, so their world

is tactile, cluttered and naturalistic. Act Two is one long scene in living time. This contrast drew me to the play.

How did you and BD Wong approach the challenge of playing an algorithm, M, who has no human motivations?

This was a brand-new play, so we learned the rules as we built it. In early drafts M was present but largely silent and therefore passive. We learned in the rehearsal process that M was most exciting when truly interacting with the other characters—when he was a thought partner who was integrated into the world in a human way.

Early on, BD felt his dialogue was hard to learn because his character didn’t have human emotions. M wants the other characters to do some things in service of capitalism, in service of “bigger and more is better,” but there’s no real emotional drive to accomplish those tasks. For example, dialogue like, “I can make your life better.” “Better in what way?” “Well, easier. I can make your life easier. Frictionless.”, doesn’t come with a

clear need behind it. It becomes a challenge to activate as M is not a robot. Not a metaphor.

I knew from reading an early draft that I wanted to work with BD Wong. He could do this! He comes from a place of real honesty, invention, great humor, and smarts, and he has an A.C.T./ San Francisco following. He was a real new-play thought partner, grounding the character. He stepped into each scene with specific purpose. With both couples, he triangulates the relationship. With one he is another lover in the room. That’s inherently compelling. Then the other couple is facing challenges about career, money, and wanting to try to have a child. M is almost like a therapist that they can talk to. He’s like a Mephistopheles character who is very charming. You want to spend time with him, even though there are warning signs that you shouldn’t get too close, but you reveal yourself anyway, because he’s taken an interest.

It’s all about focus. There’s something about social media and online platforms, where you type in a few things about yourself and they reflect back what you’ve put in, and you feel seen. That’s an interesting character and dynamic

to have on stage, a person who can challenge and push, but who is only challenging and pushing you to the places that you’ve already stepped into.

How did you and your collaborators hone in on the design choices you made for the first act, which is so technology-focused?

We wanted this liminal, open space. The play was being done in the Toni Rembe Theater at A.C.T., which is a 1,000-seat house and a big, voidlike space. I was interested in color on the set walls, even though I knew we were going to have projections. When I think of the internet, it’s these deep blues, and everything is back-lit. There’s something buzzy about it. We wanted the world to be full of color and not black-andwhite, not some science fiction or dystopian world that would distance the audience or let them off the hook, but a seductive world of now.

The play starts with a 1950s TV that presents a prompt that says, “Press play.” When I first read the play, I thought to myself, “Oh, this smacks of doing it in a 99-seat black box. It feels like a small-room gesture. How will this be accomplished in a 1,000seat theatre?”

BD Wong in Big Data

PHOTO KEVIN BERNE

Act Two of Big Data

BD Wong in Big Data

PHOTO KEVIN BERNE

Act Two of Big Data

I was in conversation with my projection designers, Kaitlyn Pietras and Jason H. Thompson, and my wonderful set designer, Tanya Orellana, and they asked, “Okay, so where’s the button? What are they pressing?” And I said, “Oh, the button has to be on the TV screen. It has to be one of those now-intuitive triangles on its side, and someone from the audience is going to come up and press it.” And my production team asked, “What? How?” I said, “Trust me, trust me. We’re going to have to kill a couple seats. We’re going to have some stairs coming off the stage. We’re going to keep the house lights up, after the curtain speech, and then this tiny little video in the corner in a ’50s TV will come on, and then this button on the screen.”

We did have some prompts that we projected to our back wall to encourage people: “Press play” showed up in big letters, and then it said, “No, we really mean it. You’re not going to get in trouble. Please.” But we never had to wait for longer than a minute. Someone happily did it every time, and our audiences wound up being complicit with setting the whole event into motion.

The set for Act One was this open space with walls that had an infinity look, with scoops and curves. They were great projection surfaces and had some LED lighting effects on them. The projections were mainly used during transitions.

This is a play very much about surveillance capitalism, about data mining. The transitions took us into the video and got more frenetic as the character of M egged the two couples on. We also had a bit of live video in some early scenes. There’s something great about having a live closeup of someone who is on stage, so we can look at them in a different way, the way this algorithm is learning about this person, their nerves, their nervous ticks.

The characters who were being projected live noticed that their image was on the wall, because part of the story we wanted to tell is that we let these things in. We click “agree” without reading the pages and pages of “Do you want to change your privacy settings? Do you accept all the cookies?”—all that kind of stuff. We’re constantly—going back to the beginning of the show—we’re constantly pressing “play.” We want this distraction.

So even in a moment of having an intimate conversation about “Do you think about having kids?”, having an intimate conversation with a stranger, suddenly a character would notice on their home wall that their image was getting projected, and I had the actors find the camera, be okay with it, and continue.

How did you and your team help ease the audience into the different feeling and style of Act Two?

The play was first written to be intermission-less, and we were going to have an a vista set transition that would dump us into this new world that was prop-heavy and naturalistic. We couldn’t shrink the play down enough for North American sensibilities to sit still that long, so we did put in an intermission. But we didn’t want to lose the idea of Joe and Didi in living time, so we did the set transition a vista still. We had the liminal world of Act One break apart and the Act Two set come downstage. The actors playing Joe and Didi were on set in the transition, and then populated it throughout the intermission. Their life started at the end of Act One and continued in living time: sitting on the sofa, reading the paper, going in and out of that living room. So we still accomplished that notion of tactile living time as written and as performed.

Some of what Act One is about is the negation of being present, of being okay with a moment of breath. In Act One, we were constantly filling our time and being told that we should be maximizing every second, whereas Act Two does not have that feel, and so that’s very much on stage. For instance, there is a moment when both actors leave the stage empty for 50 seconds, and the audience gradually notices a ticking clock, collectively enjoying the simple passage of time together before the action of the story continues before them.

What’s been most interesting or challenging about this production?

I think it is going back to some fundamentals, as always. Really grounding the play in human and visceral scene work with this topic. You can’t play a metaphor. Audiences actually do like to participate. Simple magic is the best magic. All that stuff felt difficult at times, but in the best way.

Pam MacKinnon currently serves as A.C.T.’s Artistic Director. She is a Tony, Drama Desk, two-time Obie, Lilly, and Callaway Awardwinning director and the most recent pastPresident of SDC.

In a conversation with SDC Journal, SDC Associate Member Arnaldo Galban spoke about his experience with theatre and directorial style in Cuba, where he was born and began his career as an actor and director, and in the US, where he recently completed a Stage Directors and Choreographers Foundation Observership

with director Saheem Ali on his production of Buena Vista Social Club at Atlantic Theater Company. Buena Vista Social Club dramatizes the making of the beloved Cuban album of the same name, following the stories of a group of veteran musicians as they record the classic songs. The show was Galban’s first experience with professional theatre in the United States.

In Cuba, we have so many talented artists but all the cultural institutions, all the venues, belong to the government, which means they’re paying your salary and they’re producing your plays. They can attend performances before opening night, watch what you’re doing, and decide if you’re opening or not.

Independent theatre is illegal in Cuba, because that means you’re doing theatre with your money, so the government can’t censor it. You can’t do theatre outside the institutions, and you can’t sell tickets.

The government won’t say, “Oh, we don’t allow independent arts in Cuba,” but they will make sure that you can’t make independent theatre.

I had friends doing that work. They were put in jail, or they were threatened. It’s a very difficult environment if you want to be a free thinker and create something. Which is crazy, because the Cuban Revolution has invested so much money in cultural things in Cuba. You can go to a cinema for a few cents, or you can buy a book and it’s less than a dollar. Everything that’s cultural in Cuba is so affordable. They’re giving culture to the people, and at the same time asking you not to use your brain, which is so confusing.

As a young artist, you’re very confused, but also it gives you that kind of rebel spirit that says, “Oh, you don’t want me to do that? Now I’m going to do that, and I don’t care if I’m not making money.” It’s beautiful; you do it because you really want to do it, because you love it.

What was your directing experience like there?

I was directing, I was designing, I was building the lights. I learned that from one of my favorite teachers and theatre directors in Cuba, Nelda Castillo. She made everything in the theatre with her hands. I learned that from her. I built lights with tomato cans. I built whole electricity systems. It was an adventure.

What was your concept of a director then?

In Cuba, we don’t have a place where you can study directing. You can study as a playwright, a designer, an actor, a critic, but not a director. Almost all the directors I worked with in Cuba learned to direct by trial and error while they were actors in a very important company called Teatro

Buendía and the director there supervised their processes.

Those directors inherited skills from her, but they also inherited her style. In Cuba, the director has the last word on everything. They tell people what to do all the time. That happens everywhere in Cuba: in your house with your dad, in all different kinds of work environments. But in theatre, they use a very tyrannical style. That’s the way I grew up, seeing these directors call actors names or humiliate them in front of the rest of the company. I think we inherited that because of politics in Cuba. Our authority model is, “If you are not with me, you’re against me. You’re the enemy.”

I learned a lot from the directors I worked with there, and I will always be grateful for that. But I think in Cuba, no one realizes

we’re following a model or a style that is against creativity. Especially with theatre; it’s such a communal art. And I think that’s what I saw here with Saheem Ali on Buena Vista Social Club. In America, you are in a creative process, and you are co-creating with all these people that are part of the creative team.

How was Saheem’s style of directing different from your previous experience watching directors work?

Well, first of all, Saheem is so kind. He learned my name. He said hi to everyone. He took time to acknowledge that we were present in the room. He even took time to unite the company and have everyone introduce themselves, and ask, “How did you arrive here?” and “What is your connection with the material?” I saw people hopping up and sharing deep and emotional stuff, because he was able to create this environment that made people feel safe to share.

That’s him, that’s who he is as a person. The people he feels comfortable working with are also people with this style. They are very human, and humble.

Saheem also considered other people’s ideas. If he was talking about something, and he had an idea, and then someone suddenly realized, “Oh, there is this way of doing this,” he was able to say, “Oh, yes, let’s try that.” My previous experience with other directors was that they respond to other people’s ideas with, “Oh, I didn’t have that idea. I know it’s amazing, but I won’t say that, because that means you are more creative than me, and I can’t put my work at risk.” Saheem was able to be open and say, “Let’s try that,” and the show got richer and richer.

Does that style inform how you think about making work now?

The way I will approach the next thing will be different thanks to the experience I had with Saheem. I would love to imitate his style of inclusive directing, listening to everyone, being humble, that kind of thing.

I feel lucky to meet people who are showing me there’s a different way to be a star and a different way of being a talented director, and that doesn’t mean you feel you are above everyone.

Arnaldo Galban is a director, actor, and acting coach based in New York City.

Roberto Romero in La Estática Milagrosa in Cuba, directed by Arnaldo Galban PHOTO C/O ARNALDO GALBAN Eugenio Torroella in La Estática Milagrosa in Cuba, directed by Arnaldo Galban

Theatre director and writer JoAnne Akalaitis has been a vital, commanding, and uncompromising force in American theatre for more than 50 years. She developed her theatrical language—which, she says, was most informed by art and film—early in her artistic life in Chicago, San Francisco, Paris, and New York. Akalaitis co-founded the pioneering theatre collective Mabou Mines in 1970 with Lee Breuer, Philip Glass, Ruth Maleczech, and David Warrilow. Her body of work—for which she has been awarded a Drama Desk Award and six Obie Awards for Direction and Sustained Achievement—includes plays by Beckett, Churchill, Euripides, Genet, Kroetz, Pinter, Shakespeare, Strindberg, and Williams, among many others. She was inducted into the Theater Hall of Fame in 2023.

Akalaitis met Charles Newell in 1987, when she directed an adaptation of two works by Georg Büchner—his play Leonce und Lena and his unfinished novella Lenz—at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, where Garland Wright was in his second season as Artistic Director and Newell was the Resident Director. Two years later, in 1989,

Newell assisted Akalaitis on a production of Cymbeline for producer Joseph Papp’s Shakespeare Marathon at The Public Theater/New York Shakespeare Festival, featuring a diverse cast including Joan MacIntosh as the Queen and George Bartenieff as Cymbeline, along with Joan Cusack, Wendell Pierce, Don Cheadle, Jesse Borrego, Peter Francis James, Michael Cumpsty, and more.

Celebrated by its many admirers and reviled by much of the press, Akalaitis’s staging was notoriously excoriated in The New York Times by Frank Rich, who wrote—among other criticisms—“While one can applaud Ms. Akalaitis for casting a black actor [Wendell Pierce] as Cloten, doesn’t credibility (and coherence for a hard-pressed audience) demand that his mother also be black? Apparently not, since the Queen is reserved instead for a favored Akalaitis leading lady, Joan MacIntosh.... It’s productions like this, which practice arbitrary tokenism rather than complete and consistent integration, that mock the dignified demands of the nontraditional casting movement.” The production, and Rich’s review, inspired a special section in American Theatre, “Cymbeline and Its

Critics: A Case Study,” by Elinor Fuchs and James Leverett.

In 1990, Akalaitis was handpicked by Joseph Papp to be his successor at The Public/NYSF; she served as artistic director for 20 months before being fired by the theatre’s Board, who referred to the period of her leadership as a “time of transition.”

The following year, when Newell began what would become a 30-year tenure as Artistic Director of Court Theatre, he invited Akalaitis to work with him there. As artist-in-residence she directed seven productions at the theatre over the next 10 years. And she has remained busy, directing at regional theatres and in New York, where she conceived and produced the María Irene Fornés Marathon at The Public Theater in 2019 and most recently directed Fornés’s Mud/Drowning, the latter as a new opera by Philip Glass.

As an educator, Akalaitis has served as the Andrew Mellon Co-Chair of the first directing program at the Juilliard School, Chair of the Theater program at Bard College, and the Denzel Washington Endowed Chair of the Theater at Fordham University.

JoAnne Akalaitis photographed at homeCHARLES NEWELL | Where did your interest in theatre begin, and what were some of the important influences when you were young?

JoANNE AKALAITIS | I went to a Lithuanian Catholic school called St. Anthony’s School in Cicero, Illinois. It was a uniquely isolated environment of Lithuanians and a few Italians. I remember the rich, theatrical Catholic pageantry in our church. I loved it. I always felt sorry for other religions because they didn’t have that sexy, bloody, juicy religious iconography in their lives.

I was also lucky enough to go to a really good all-girls Catholic school, Providence High School, where I was educated by incredible women, including my art teacher, Sister Edith. At that time I wanted to be a visual artist. She did so much for me—she introduced me to Picasso and she gave me and a classmate one of the school’s walls to design and paint a mural. Like many theatre artists, I was influenced by my drama teacher—in this case, Ms. Cluny. It was thrilling for me to be in her productions. At the same time, I was going to productions at the Goodman School of Drama’s famous children’s theatre and learning about painting at the Art Institute of Chicago. The defining moment was when my Mom took me downtown to the Chicago Theatre where I saw Mary Martin in South Pacific. What I was seeing was an art form where everything was possible. Where a woman could wash

her hair on stage, at the same time singing about some dopey guy.

When I went to the University of Chicago, I saw Cocteau’s Blood of the Poet. I made a deep connection to it; there was something in it that was telling me where to go. But at the same time, I was thinking that I was too ordinary and not glamorous enough to be what I thought women became in theatre, i.e., actresses.

CHARLIE | What was your trajectory toward finding your place in being a theatre artist?

JoANNE | I ended up performing in student productions all during college. When I continued on to Stanford to pursue a doctorate in philosophy, I was cast as Beatrice in a university production of Much Ado About Nothing. I also took an acting class and I thought, “Boy, this is easy, much easier than philosophy and logic, certainly.”

And then Alan Schneider came to Stanford to direct [Brecht’s] Mann ist Mann. He was auditioning not only everyone at Stanford, but also professional actors from San Francisco, including Ruth Maleczech. I got cast as Widow Begbick, and I think I was pretty bad in it. Except Alan was such a great encouragement. All my life, all his life, he encouraged me. I would see him through the years. And of course, my Beckett productions were so different than his

Beckett productions, but there was never any reprimand. He always said, “Baby, what you do is so different than what I do, but you do it.” I think you knew Alan, didn’t you?

CHARLIE | I did. I assisted him on Pieces of 8 for The Acting Company, a series of one-act plays that he conceived and directed, my favorite being The Tridget of Greva, which was a short one-act that Ring Lardner wrote. And then that summer he stepped out in front of a motorcycle in London and died.

JoANNE | He did, mailing a letter to Beckett, I read.

CHARLIE | You moved to San Francisco in 1962. What was that like?

JoANNE | It was a series of fortuitous events. I met Ruth and Lee [Breuer] in Marines’ Memorial Club in San Francisco, in the coffee shop downstairs from Herb Blau and Jules Irving’s Actor’s Workshop. I auditioned to get into the Workshop and didn’t get in. After the audition, I got a job selling orange juice in the lobby. San Francisco at that time was a hotbed of experimental art, early Happenings, site-specific performance, and new music. Growing up in that world of performance and art created a very, very rich soil for me. Stan Brakhage, the filmmaker, was there, as was Ramón Sender and Morton Subotnick at the San Francisco Tape Music Center. I studied with R.G. Davis, founder of

the San Francisco Mime Troupe. Ruth and Lee and I started working on our own theatre experiments. Once, during an investigation of Antigone, I threw a chair out a window, but luckily didn’t hurt anyone. All of this gave me a taste for experimentation, but I still thought I wanted to be a (real) actor in a (real) play.

I went to New York, and it became clear to me that the theatre system wasn’t going to work for me, because of my personality or whatever. Then I reconnected with Philip Glass, who I had met on a trip he had taken to San Francisco on his motorcycle. He got a Fulbright in 1964, and I joined him in Paris. We lived in a small garage atelier. Phil played the piano all day—he was studying with Nadia Boulanger—and it drove me crazy. So I went to three movies a day at the Cinémathèque and it was a profound education. I learned about people like Alain Resnais, Agnès Varda, Jean Vigo, and of course, Godard and the New Wave. My work continues to be influenced by film, most notably by the work of Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Right now I’m following the work of Claire Denis, a French film director. Her film Beau Travail is an adaptation of Billy Budd, and it’s astonishingly brilliant. And I love Kelly Reichardt.

CHARLIE | How did your time in Paris lead you to Mabou Mines, which was founded at a time when there were no boundaries

between artistic disciplines? How was this reflected in the work of the collective?

JoANNE | When Philip and I came back in 1966, everything was happening in New York. There was no hierarchy, everyone was hanging out together and doing stuff together—musicians, visual artists, performers. It was such an exciting time. We were all equal and creating together. That’s what Mabou was. Everyone was equal. We all ended up living on two floors for $75 a month. Philip built a music studio on one end and a rehearsal studio on the other.

Everybody was everything. So everyone could be a designer, an actor, a director, and we were always directing each other. Lee was the first actual director, a writerdirector. But we were saying freely to one another, “Maybe that doesn’t work. Maybe you should try this or this, or that kind of costume or that lighting.” The unspoken contract was that one could articulate any criticism or suggestion. And everyone got to do what they wanted to do. So if someone wanted to do a show that was not my “aesthetic” or my politics, well, the deal was that person got to do that show.

CHARLIE | Did that come about just by who you all were? Or was there some core guiding principle of aesthetic or process?

JoANNE | I think it happened to be in the stars that this group of people got together. It was a group of people who wanted to run their own business. So everyone got paid the same amount of money, whether one was working or not. Perhaps most important was acknowledging the importance and presence of children and family in the community of Mabou by including a babysitter in every budget. It was called, for the purposes of accounting and the IRS, “rehearsal assistant.” And indeed, that babysitter was a true rehearsal assistant. There couldn’t be a rehearsal, and certainly not a tour, without childcare. Our first tour, the first stop on the tour, Minneapolis, we had a babysitter with us. I had a two-and-a-half-year-old and a ten-month-old with me.

CHARLIE | Can you talk more about the first tour, just how that evolved and how that happened?

JoANNE | Sue [Suzanne] Weil, who was running the performance series for the Walker Arts Center, invited us. We stayed in her enormous house in Minnetonka. She was such a discoverer of the arts. Not only was she the first one to book Merce Cunningham, Philip Glass, John Cage, David Gordon, Mabou, Trisha Brown, Meredith Monk—at the same time she was booking stars like Miles Davis, The Who, and Led Zeppelin. The tour went on to San Fransisco, LA, Portland, and Washington state. Phil drove the truck

and we all loaded-in, installed, and loaded out the scenery.

At that time, Ellen Stewart [founder of La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club] was also crucial because Ellen gave us our first salary. It was $50 a week. We could pay a babysitter and we could manage the food and rent. We were paid for being artists and it was a big deal.

CHARLIE | I know that you’ve called Ellen Stewart and Joe Papp your mentors. How did they challenge you or the collective of Mabou?

JoANNE | If encouragement can be seen to be rising to the challenge, that’s how they challenged us. They were so much alike and yet so different. What they shared was acting instinctively, which meant that some of their instincts were absolutely nutty and some of them were brilliant. But I learned an important way of thinking about the work.

“Let’s just keep trying... let’s try it. Oh… oh… it’s good. This is going to be over budget. Let’s just try it.” Joe always said, “Make the art and the money will follow.”

I remember when Mabou Mines was rehearsing at New York Theatre Workshop, where Jim Nicola was another incredibly generous leader. We were rehearsing Dressed Like an Egg, which I made from the writings of Colette. And I invited Joe to rehearsal. He came with Gail [Merrifield Papp, head of The Public’s literary department and Joe Papp’s wife] and said, “Oh, you’re artists. Come over to The Public tomorrow.” That day, Joe gave me a storefront theatre on Great Jones Street. Later that very same day, the executive director or the managing director of The Public Theater took it back because Joe couldn’t afford to give it to me.

CHARLIE | But he did it anyway.

JoANNE | Yes. He said, “This is yours. Do whatever you want.” Joe and Ellen had a kind of autocratic, artistic leadership style, along with an instinctive, encouraging belief in art, in making theatre, and in artists. When Ellen got her MacArthur, she bought a place in Umbria to be a residence for training actors and directors and playwrights.

CHARLIE | Tell me more about the evolution of your work through Mabou.

JoANNE | Well, I wouldn’t be a director without Mabou. I was an actor for a very long time, and I was unhappy. I hated it when the show opened, and we had to repeat. For me it was just repetition; for a really gifted actor, it’s continual discovery. I don’t have that gift. I’m most interested in rehearsal, the process. Really, there was no room in

Joseph Papp + JoAnne Akalaitis PHOTO MARTHA SWOPE/NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY

my creative being for that kind of constant rediscovery and invention. It’s one of the things that I admire so much about actors.

Once I directed my first show at Mabou, Beckett’s Cascando, I knew I’d never stop directing. My leaving Mabou was very natural. I was interested being out in another world, in working with people that I didn’t know, and tired of the collective and endless meetings.

CHARLIE | I can imagine many names, but who have been the most influential collaborators of the theatre design folks that you’ve worked with?

JoANNE | I think every designer ever. Certainly Jennifer Tipton, Kaye Voyce, Gabriel Berry, John Conklin, Susan Hilferty, Eiko Ishioka, Doug Stein, George Tsypin, Paul Steinberg, Thomas Dunn, all of them. They each work differently. Isn’t that the case for you?

CHARLIE | Absolutely.

JoANNE | You get together with a designer and maybe there’s not much conceptual conversation because you kind of get one another, but at the same time, the ideas flow. For example, for The Trojan Women, Paul Steinberg and I went from an empty ballroom

to an abandoned office building. Working with these designers, every door is open.

The actors and the audience meet in this common collective subconscious ground, which is magical.

I have a deep conceptual, intellectual, dramaturgical alliance with my designers. Designers like Kaye Voyce and Jennifer Tipton are real dramaturgs. Plus, they love actors. They don’t just show up for tech. They come to rehearsal. I welcome their directing notes, and notes on the shape of the piece.

CHARLIE | What is your rehearsal process— how do you begin?

JoANNE | With movement. Especially in the beginning of the process, when we often do several hours of movement. It continues after. There is always a physical warmup and often an actor-led vocal warmup. Personally, I can’t just walk in the room and begin rehearsal. I need to be with the actors in a nonconceptual, spatial way before we begin with text.

I don’t do table work. I can’t. I’m too impatient—except for Greek or Shakespeare plays or text-heavy things. Which is not to say that kind of investigation doesn’t happen, it just happens later. First is the physical work, getting the bodies in space. The movement exercises have evolved over the years, like the exercise “Stopping and Starting,” which I do with every show. It’s simply moving through space to an Ethiopian Afro-beat tune, arbitrarily stopping and then starting, which then evolves to the group forming organic compositions. This is a physicalization of an important quote from Genet’s notes to the actors for The Screens, where he asks them to take each scene and each section within a scene as if it were an entire play without any smudges, without the slightest notion that there is another scene to follow it. That idea is essential to my work.

The kind of theatre I’m interested in is a theatre without transitions, where you keep falling off a cliff. And that’s dangerous. It’s dangerous for the actor. But there are some actors who will take a chance in rehearsal and it proves to be tremendously exciting. I always thought that Ruth Maleczech was certainly one of those where you never knew what she was going to do next. At the same time, her entire script was covered with writing, with notes, and she was the last person to go off book. In fact, I had to beg her to.

CHARLIE | Seeing Ruth in your production of Through the Leaves with Fred Neumann, I had no idea what was going to happen next. Can you speak about what you refer to as the Mudras in relation to the physicality of the actor?

JoANNE | It’s my own kind of borrowing of the Kathakali theatre from Kerala, India, which is my favorite theatre. It’s cross-cultural, cross-everything, and tells enormous stories from [the Hindu epics] The Mahabharata or The Ramayana. It’s not that we don’t have those big stories—we do in Shakespeare and the Greeks—but the fact that there are these signals, these signs. I see them as iconographic, nonverbal, nonintellectual gestures, on the stage, perhaps abstractions of what we have in the West, which is psychology, as opposed to in the Kathakali, where there are codified, universal facial masks of jealousy, anger, and fear.

The masks that I do are sort of abstractions of Western psychology. They’re not set, they’re very fluid, and often they’re inspired by something visual. I’m interested in using visual art in the work always. For example, in Mud we used Philip Pearlstein’s luscious nude paintings and the poses in the 17thcentury Spanish painter Zurbarán’s work. In the end, it’s all really messy and a lot of it is, “Hey, let’s do a Mudra here.” I also owe a lot to ASL, which I find myself incorporating more and more in my work. I’ve also used slow-motion for years. I like things very fast or very slow.

CHARLIE | At the first rehearsal for Leon & Lena (and lenz), my memory—and correct me if I’m wrong because I’m sure there were

lots of other things going on that I was not aware of—is that there was a way of creating the space, the room for the actors. We put on music and people started moving about the space, and you used the phrase “Walk through your life.”

JoANNE | Lee Breuer came up with that exercise based on what Ruth and I learned from our workshop with Grotowski in Aix-en-Provence. The exercise is basically walking around the room, one minute for each year of your life, starting with year one. You have to be open to any image from your own life that comes to you, no matter how trivial, with the possibility that it can be vocalized or physicalized. It’s amazing.

I took my little six-month-old daughter with me to that workshop, and lied to Grotowski, who did not believe that women who were mothers were capable of doing his work. And Ruth was pregnant. It was so hard. My Grotowski story about my crawling through the transom to nurse the baby in the hotel is pretty well known by now.

I got several things from Grotowski; one is to be fearless. Part of his teaching is that you don’t become the character. You only have these moments in your life. That seemed to me to be an absolutely revolutionary idea about acting and about creating a score for a production.

I’ve been involved lately in having very short rehearsal periods, which I like a lot. It creates a kind of edgy rehearsal and performance. At the same time, I could not have done certain shows—like The Iphigenia Cycle in Chicago or Bad News! at Bard College and the Guthrie—without the luxury of workshops beforehand.

CHARLIE | Indeed, indeed.

JoANNE | I am not that attracted to the European model, especially the Eastern European model where they rehearse for six months and then they do a production, often a male director’s vision. I leave a lot to the actor. The actors are working in their bodies, which leads to their souls and their minds and their craft, their natural ability to create composition. I don’t block anymore because the actors do it better than I do. Which doesn’t mean I don’t constantly adjust the composition on stage.

One example of actors creating and owning their own community was The Trojan Women at the Shakespeare Theatre in DC

Fred Neumann + Ruth Malaczech in Mabou Mines’s Through the Leaves, directed by JoAnne Akalaitis

PHOTO C/O MABOU MINES

Fred Neumann + Ruth Malaczech in Mabou Mines’s Through the Leaves, directed by JoAnne Akalaitis

PHOTO C/O MABOU MINES

with Nick Rudall—a great leader from Court Theatre and the University of Chicago, who also was such a valued, wonderful colleague, such a man of theatre. I asked the Chorus to shave their heads. These actors came in to audition with gorgeous hair, and I said, “Oh, there’s just one thing, you have to shave your head.” We decided on a date, a time. They wanted a woman barber. They went out the night before by themselves and got drunk and ate a lot of food. I was not invited to the shaving. But Jesse Berger, my assistant, went and he got his head shaved. Then they came over to my house for margaritas and dinner. They looked fabulous, but more importantly, they had created an exclusive tribe.

CHARLIE | What role does the audience play for you?

JoANNE | The English playwright Aphra Behn, who was the first woman to earn her living as a writer in English, said, “Theatre is a place where secret signals are sent to the audience.”

Now, she happened to be a spy, and that’s what she meant. But I’ve turned those words to my own use. Yes, we are sending signals to the audience, and the audience is maybe sending their signals back, and the actors and the audience meet in this common collective subconscious ground, which is magical.

CHARLIE | My experience as an audience member when I see your work is that I get to have my own response because there’s so much opportunity being offered through the signals. In other words, I can find myself in it. I don’t feel like I have to get it the way that you as the director wants or intends me to. Can you speak about that at all?

JoANNE | I don’t ever think that way, that there’s something to get. But the making of theatre, of course, involves our intelligence. The audience has to work hard. In the beginning of Stereophonic, which Daniel Aukin directed, in the beginning I thought, “Oh my God, they have such thick English accents and they’re talking so fast.” I could hardly understand them. “I love this. I love this.” I thought it was so much fun that I had to work so hard.

CHARLIE | JoAnne, my sense is you ask an audience to work really hard, and then people need to assign some name or quality to you—such as an avant-garde director who is doing radical interpretations of text—as a way to understand their feeling. What’s your response to being given such definition?

JoANNE | I don’t get it. I mean, I am just a worker in the field. The avant-garde flowered with Gertrude Stein and Man Ray. That was ages ago. The whole thing of auteur or director’s theatre, that really has no meaning because the theatre belongs to all of us—the

audience as much as it does the director, the writer, the actors, the designers. It belongs to all of us. We all make it together.

CHARLIE | I’ve done many things with you that I’m proud of, and Cymbeline was one of them.

JoANNE | Oh my God, wasn’t that the most tiring, crazy...? We would have three rehearsals going on in different rooms at the same time.

CHARLIE | I remember it well. You would send me off to a room with Joan Cusack.

JoANNE | Praise Joan because she wanted to know what every single word meant.

CHARLIE | It was extraordinary. I mean, just so many performances. But I also remember the critical response from the New York Times

JoANNE | I was going to Minneapolis the day after opening to audition actors for Genet’s The Screens, which is set during the Algerian Revolution of the 1950s and ‘60s. We had a cast of more than 50. I was determined to interview every non-Equity, non-white actor in Minneapolis, including people who had never been on the stage, a woman who felt so panicked the only way she could audition was with her back to me facing a corner. I auditioned 80 actors in one day after reading that Frank Rich review.

The Trojan Women at Shakespeare Theatre Company, directed by JoAnne Akalaitis

The Trojan Women at Shakespeare Theatre Company, directed by JoAnne Akalaitis

CHARLIE | What a great way to respond to that.

JoANNE | The production had, not redemption, but people remember it was great.

CHARLIE | They do.

JoANNE | Ellie Fuchs did that eightpage feature in American Theatre . I meet people who saw the production. I ran into Wendell [Pierce] at the Charlie Parker Jazz Festival in Tompkins Square Park, and he said, “Ah, thanks, that was so much fun.”

And working with Phil [Glass] and the band, working with you, the fight scene [choreographed by David Leong]—it was revolutionary among fight scenes. Once again, it just opened so many doors. But the racism, for Frank Rich to say, how could a white woman have a Mexican son and a Black son? Huh? Huh? What?

CHARLIE | When I got the news that you were no longer the Artistic Director at The Public Theater, I called you up and I said, “Whatever’s happening there, JoAnne, you’ve got to come to Chicago. What do you want to do?”

JoANNE | Charlie, that was so welcome. Thanks. Didn’t you ask me to direct something, and I said I couldn’t possibly do it because it was too hard, and I didn’t understand it?

CHARLIE | Yes.

JoANNE | Well, I never direct anything I understand, but it was like—was it Thyestes, was it Phèdre?

CHARLIE | I’m not sure, or Quartet [by Heiner Müller]. I’m not sure which one.

JoANNE | Well anyway, The Public: I always say the best thing that happened to me and the worst thing that happened to me was being the Artistic Director of The Public Theater for a whopping 20 months. I actually think I was right for the position, but not in those particular circumstances with perhaps that particular Board. We did some terrific work in that brief time. [John Ford’s] ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore, Woyzeck, Fires in the Mirror, Pericles, Henry V Parts 1 and 2. It’s horrible to be fired from a big job on the front page of the New York Times. I have kept all the letters I got in a shopping bag. They’re in my house. I’m grateful to all the people I worked with and what we did. But it’s also something I don’t think that, for my mental health, I should have been doing for very long.

All the planning that is hooked into the nature of institutions is a business model. It is not an artistic model. When I was at Bard, I never wrote a syllabus. I told them what to expect. When I was at Yale, they said, “You have to have a syllabus.” I said, “Okay.” The second class, I told the students, “You know that syllabus you have? Throw it in the garbage. It’s useless. I don’t want to do those things I said that I was going to do.” It’s not that you’re not preparing. It’s the whole fiveyear plan situation. It seems like shooting yourself in the foot.

CHARLIE | If you could create a new model for what graduate schools are doing rather than what they’re doing now, that’s not about business structure, what would it be?

JoANNE | Graduate school really is a lot about craft, skill, technique. Certain language should be out, language like “the industry” or “the business,” because it is sending the wrong message. And also, they have to read something beside their sides. They have to look at art, see opera. I always took my students to museums and opera dress rehearsals.

CHARLIE | Can you imagine a theatre that is creating the art, not to serve the institution, but just because of the work itself and how it might partner with the university around

Jesse Borrego, Frederick Neumann, Joan Cusack + Don Cheadle in Cymbeline at New York Shakespeare Festival, directed by JoAnne Akalaitis PHOTO MARTHA SWOPE/NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY

the scholarship and the dramaturgy and the artists? It’s sort of putting all of us together without some of the restrictions of it being part of an institution.

JoANNE | One way is a salon model. I had a salon at Bard that went on for a couple of years. So many visiting artists came—Robert Woodruff, Anne Bogart, Bill Camp, Lynn Nottage—and such interesting work got done. It was a lot of work for me because I cooked dinner for 20 people every week. We pretty much never read theatre work; we read philosophy or theory or politics, for example Canetti, Foucault, Naomi Klein. After Bard, I had a women’s theatre salon once a month in which we read work about women. We read Strindberg, The Declaration of Sentiments from the first American Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, Hallie Flanagan, Greek plays like Antigone, and obvious playwrights like Irene Fornés and Ellen McLaughlin. The group had a great range of women from age 24 to mid-eighties and eventually included climate change activists, journalists, academics, and visual artists. It’s really important to get together and read and then see how work is connected to reading. That seems like where theatre, for us anyway, begins. It begins with some words, which sometimes become stories.

That Women’s Salon led to a group of us doing a homage to Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece at Carnegie Hall. We did it in Madison Square Park on the day of the Electoral College election in 2016—it was called Cut Piece for Pants Suit. We also did a piece called 100

Years! Stay Tuned…, celebrating a woman’s right to vote in New York State.

When I was at The Public Theater I got a considerable sum of money from the Mellon Foundation, and I did not invest it in a project. Instead, I gave different amounts to artists, inviting them to be artistic associates. All they had to do, if they were free, was once a month come to my office and we would read a Greek play guided by a Greek scholar from the Classics Department at Yale. That was a lot of fun. Eric Bogosian reading Agamemnon was really fun.

But you don’t need a lot of money from the Mellon Foundation. What if you have a little bit of money? You could do something. For example, Leon Botstein, president of Bard, was going to tear down the old gym on campus. I said, “No, give it to the theatre students. Give it to them and they can produce their own work.” And it became a wonderful student-driven venue.

CHARLIE | What’s your sense of how young people are feeling about the theatre today?

JoANNE | I think young people coming out of graduate school are so worried. They have to face the post-pandemic world, real estate, and debt. They’re worried about money, how they’re going to make it, or should they bring children into the world because of climate change? And that’s why I keep looking around the corner for the next thing to do that is where the arts will matter. I’ve always believed in the great joy of making art and making theatre art. And in how much you give to people.

The most exciting theatre artists I know are my former students. They’re worried, they’re very worried, but they’re working. I am so proud of them, and I am also proud of myself, of what I gave them—which is fundamentally idealism and in these difficult times, hope. I think in spite of myself, I am idealistic. The theatre, as we know it, is pretty injured, pretty damaged, and so expensive. My hope is that it will go on to exist in some completely new and inspiring form.

Charles Newell is Marilyn F. Vitale Artistic Director of Court Theatre, winner of the 2022 Regional Theatre Tony Award. Later this year, Charlie will transition to the role of Senior Artistic Consultant and, in 2025, he will return to Court’s stage to direct the world premiere of Berlin. Recent directorial credits include Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead; The Gospel at Colonus, co-directed with Mark J.P. Hood; and The Tragedy of Othello, The Moor of Venice, co-directed with Gabrielle Randle-Bent. Charlie has directed at Goodman, Guthrie, Arena Stage, Long Wharf, and many others and has received the SDCF Zelda Fichandler Award, four Jeff Awards, and seventeen Jeff nominations. Charlie is a cofounder of the Civic Actor Studio, a leadership program of the University of Chicago’s Office of Civic Engagement.

The Women’s Salon production of Cut Piece for Pants Suit in Madison Square Park, conceived + directed by JoAnne Akalaitis + Ashley Tata PHOTO C/O JOANNE AKALAITISThe Boston-area theatre is unique in some ways. We are a small, big city—majority-minority since 2000. That particular truth has not always been represented on our stages and in our audiences. When I joined the Boston theatre world years ago, I could not hope for the progress we now see—with talent on stage and off representing our community in authentic ways.

There is still much that needs to be done to support equity issues. It’s up to us to keep going. The artists who gathered at our roundtable are doing the hard and joyous work to make it so, along with many others representing New England stages and productions, from fringe to first-class.

We are lucky to work in a supportive and congenial atmosphere, shared across professions and productions. Like many theatre hyphenates, we teach at high schools, colleges, universities, and other academic institutions. There is a generous spirit in sharing information, collaborative partners, and casting resources. We continue the good work every week, every season—even as we face familiar artistic and audience challenges.

Our gratitude to SDC for bringing us together at Boston Playwrights’ Theatre to offer insights and reflections on our shared experiences.

ABOVE Dawn M. Simmons, Bridget Kathleen O’Leary, Megan SandbergZakian, M. Bevin O’Gara, Pascale Florestal, Maurice Emmanuel Parent + Lisa Rafferty at Boston Playwrights’ Theatre

Pascale Florestal is an Elliot Nortonnominated director, educator, dramaturg, and writer. Pascale serves as associate director for the national tour of Jagged Little Pill, Director of Education for Front Porch Arts Collective, Assistant Professor of Theater at Boston Conservatory at Berklee College of Music, and Visiting Guest Artist Professor at Suffolk University.

M. Bevin O’Gara is a Boston-based theatre director and educator. She spent three years as Producing Artistic Director at the Kitchen Theater Company in Ithaca, NY. She holds a BFA in Theatre Studies from Boston University and teaches at Emerson College and the Boston Conservatory at Berklee.

Bridget Kathleen O’Leary is a freelance director, educator, and new-play developer in the Boston area.

Lisa Rafferty is a playwright, director, and producer whose work includes documentary plays and The MOMologues series (Concord Theatricals). She is producing director of the Elliot Norton Awards and a proud member of the Dramatists Guild and SDC. She loves teaching at Bridgewater State University. Recent: MOMologues The Musical at 54 Below, Queer Voices play festival at Boston Theater Company.

Megan SandbergZakian is the Artistic Director of Boston Playwrights’ Theatre and the author of the essay collection There Must Be Happy Endings: On a Theatre of Optimism and Honesty

Dawn M. Simmons is an Elliot Norton Award-winning director, producer, playwright, administrator, cultural consultant, educator, and Co-Producing Artistic Director of Front Porch Arts Collective.

LISA RAFFERTY | What’s one word, phrase, or sentence that describes your work in theatre right now?

MEGAN SANDBERG-ZAKIAN | New plays.

MAURICE EMMANUEL PARENT | Reactionary.

DAWN M. SIMMONS | Ever-evolving.

M. BEVIN O’GARA | Empowering. Blowing it all up to empower others.

BRIDGET KATHLEEN O’LEARY | I was going to say making space, but now that sounds like yours and we already have similar names.

PASCALE FLORESTAL | Radical. I only believe in work that’s going to make change or at least create conversation and a dialogue.

LISA | What fuels you? What charges you?

MEGAN | I am fueled by faith—by a sense of optimism and hope that it is possible to create a space where we can be in a room together and have an experience of our essential interdependence that reminds us of the truth of how connected we really are to each other, so that we can perhaps treat each other a little better in the world outside the theatre.

What I love about the New England theatre ecosystem, especially Boston, is that I find so much inspiration in what my friends and my peers are doing.

DAWN M. SIMMONS

Maurice Emmanuel Parent is an award-winning actor, director, and educator. His selected directing credits include SpeakEasy Stage, Lyric Stage, Central Square Theater, Greater Boston stage, Actors’ Shakespeare Project (Elliot Norton Award, Outstanding Director). He is CoProducing Artistic Director of Front Porch Arts Collective and Professor of the Practice, Tufts Department of Theatre, Dance and Performance Studies.

MAURICE | I’m finding that, as a very much still-early director, I have to let the purpose of the playwright completely define my process—the questions I ask, what I bring to the table as preparation work for the actors, the container I create for them to play in, the sandbox I’m setting. It all has to come out of what I am connecting to about what the playwright is wanting me to say, at least the way I interpret it.

DAWN | Anything and everything. My own ambition, the success of my friends, a good script, something I saw at a museum, a song, something I wrote, an idea. Inspiration comes from anywhere and I think it’s important to keep filling up the well. That’s the kind of thing that fuels me.

Ken Baltin + Shawn K. Jain in Heartland at New Repertory Theatre, directed by Bridget Kathleen O’Leary

PHOTO CHRISTOPHER MCKENZIE

Much Ado About Nothing at Commonwealth Shakespeare Company, directed by Megan Sandberg-Zakian

Ken Baltin + Shawn K. Jain in Heartland at New Repertory Theatre, directed by Bridget Kathleen O’Leary

PHOTO CHRISTOPHER MCKENZIE

Much Ado About Nothing at Commonwealth Shakespeare Company, directed by Megan Sandberg-Zakian

What I love about the New England theatre ecosystem, especially Boston, is that I find so much inspiration in what my friends and my peers are doing. I want to keep playing in this sandbox for as long as I can.

BEVIN | Not knowing. That sense of, “I don’t know what it is, but it fascinates me.”

Particularly right now as an educator, what I’m really enjoying is going back to the basics of things I thought I knew and being like, “Oh, I just did that on instinct, but what is it that I’m actually doing?” Also the sense of the discoveries I make, because my students tell me new things every day. And I’ll say, being 40 now, it is great to be like, “I don’t have any goddamn clue what the hell I’m doing.”

Seeing the future in young people really fuels me for the possibility and the optimism and the faith I have that there is a different way and we’re going to find it, and we’re going to be able to recreate it in a place that everyone can access it.

MAURICE | Yes! Tell the children. They think they know everything. The older I get, the less I know.