7 minute read

Ann Reinking: A Beautiful Legacy Lives On

BY JESSICA REDISH

The loss of Ann Reinking hurts quietly in my heart today.

Until her loss, I didn’t realize how much she is in my brain, in my soul, my spirit, and my work, and I am so lucky to have known her briefly. Before it becomes a reality that she is gone, I want to get this all down so I remember, and so everyone knows. While she is being remembered for the exquisite dancer she was and the choreographer she became, I thought it was important to put down in writing the impact she had on so many members of the theatre community through her apprentice program for high school and college students, the Broadway Theatre Project in Florida. This program shows so much about her character and her lasting impact.

I now work as a director and choreographer in theatre and film, and I am currently focused on creating works of comedy. The night before Ann passed, I had the impulse to write her and thank her for pointing me in this direction, as I was beginning to have some distinct success. Working with her showed me where I should go at the impressionable ages of 18 and 19—at the apprenticeship’s final performance, I performed a big comedy scene and I realized her guidance made that possible. Her values and teachings are fully a part of me, and she taught me lessons I hope to carry on in my work, leading by example on set or in a rehearsal room. These include a commitment to excellence, demanding this of oneself and others; backing away when necessary to let an actor shine; and creating damn fine transitions.

When I went to the Broadway Theatre Project, I was challenged, humbled, pushed to my limit. I hadn’t been around that level of dance excellence before, and I met people from all over. I would say, “I’m from Chicago— the city!” in a never-ending and fruitless competition with the daring musical—the reason why, of course, we were all there. For our culminating performance at the cavernous and gargantuan hall that was the Tampa Bay Performing Arts Center, I got the opportunity to act in Charles Ludlam’s humorous riff on MEDEA and play the titular role. I remember cracking up a room of people during rehearsal and especially Ann, who was hilarious herself, and this was great encouragement.

Jessica Redish + Ann Reinking at Broadway Theatre Project

Annie—as she was known to those who worked with her—knew quality when she saw it. She was a regimented artist in that—well, technique is freedom, and Annie brought this poise and confidence with her wherever she went. The demands of training in ballet offered her a perspective and clear lens of what was hard work and what wasn’t. This, combined with an unadulterated sense of class and kindness, was how Annie made her impact on so many of us.

Annie called upon her colleagues to come to Florida and work with us or for a Q&A. In the period I attended, I took dance classes with Gwen Verdon and heard Stanley Donen speak about filming SINGIN' IN THE RAIN , a conversation that has stuck with me to this day as a filmmaker. We heard from Marilu Henner, James Naughton, and Jeff Calhoun—and I remember feeling the vibrations of Gregory Hines’ footfalls at his master class. It was one of those hypersurreal out-of-body experiences, and I told myself, “Don’t ever forget this.” It’s incredible that Ann not only influenced us but also brought her community of artists to teach us in aspects and ways different from her own: this was a lifelong gift and speaks to her generosity of spirit.

I hadn’t talked to Annie in some time, but I have worked with so many members of the faculty and apprentices that, in truth, I felt like I had. The last time I saw her was when I had the honor of assisting her at Broadway Under the Stars in Bryant Park. It was a truly magical experience. I watched as Annie led the room with grace and danced fluidly with Bebe Neuwirth. She communicated with dancers best, because this is what she was, but she was also a tremendous actress and knew how to let a performer do their best work.

When Ann Reinking singled me out at the audition for the Broadway Theatre Project, her blue eyes piercing me with their very being, and told me I had “a beautiful body roll,” I thought, here is the keeper of the legacy telling me my improv body rolls are flawless and I can do this, in the storied 890 Broadway studios, no less. As an 18-year-old, this was everything. That’s the power she had: she was a massive pro with a legendary history who was committed to helping young people. She could see you, and you knew you had something to offer. She gave me confidence in myself, and I saw her do that for so many other young artists as well.

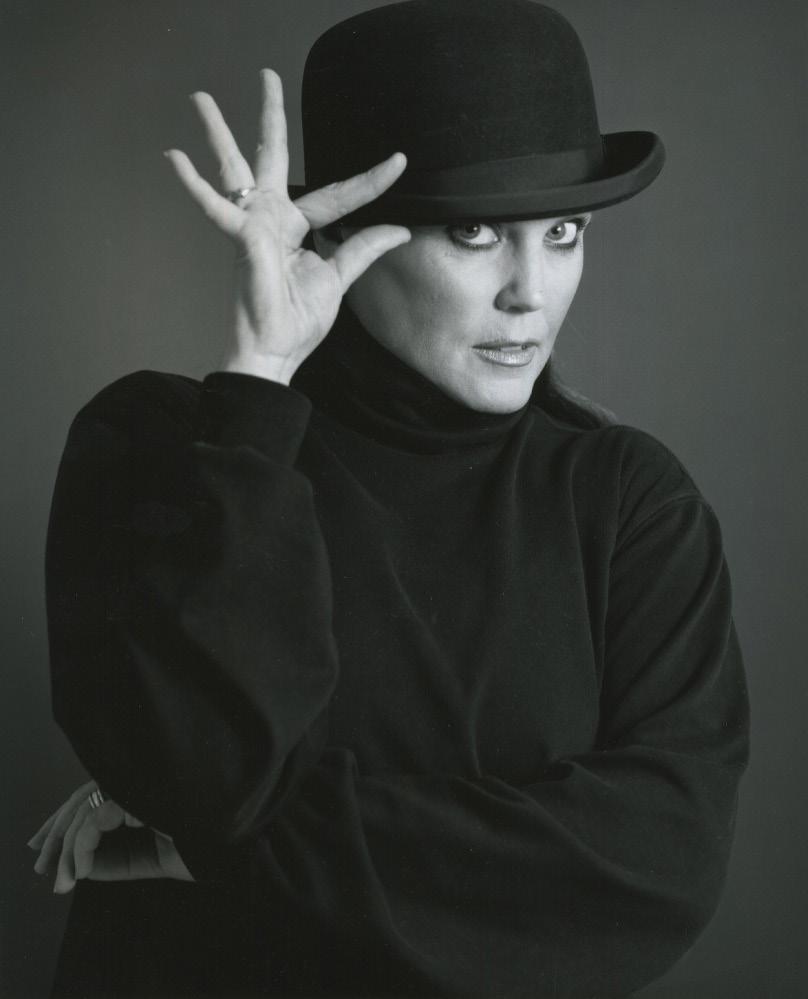

Jessica Redish + Ann Reinking

She also taught me how to lead a room. She would be firm and gently demand we show up, fully; every time we walked on stage was an opportunity to tell a story and use our technique to uplift or change an audience. She did not take it for granted and instructed us very clearly not to as well. Sometimes, she would be very definitive about this. If she felt we weren’t delivering on a song or performance, she would come to a rehearsal and look at us with her blue eyes and remind us this material has already done its work; it had already “won its Tonys,” it had already been celebrated, and we needed to step up in order to meet the material—that it wasn’t the material’s problem, it was us. And she was right. When I meet a piece of text now, I treat it with the respect it deserves.

Ann was also very maternal—she would cry while we sang an emotional ballad, take a tissue out from her purse, and dab her eyes with it. I appreciated that she was so unabashedly emotion-forward in this way. She was one of us, experiencing what we were experiencing emotionally; though she was a director, she was always somewhat of an ensemble member—always a dancer. She made it clear that dance was not a selfish endeavor. It’s not about you; it’s about the beauty you can bring to the story already being told, and the way in which you fit into it. I mourn not only for Annie but for the values she instilled in all of us, because I think, in the moment of selfies and 60-second flashiness on social media, the opportunity to be selfless might be, to paraphrase the Roxie monologue, “passing us by.”

Ann had high standards and if she thought you had it, she brought you in the room with her; if you didn’t, she didn’t, because it wouldn’t be fair to anyone. She taught me to be equally demanding of my peers, maybe sometimes too demanding (but really, what else are we doing here?). She did not play around. She only seemed to be rattled when she felt like people would mess up—not just that they made an error but that she thought they weren’t trying or, more so, that they had more to give. So we would give. Otherwise, her graceful demeanor would ingratiate herself to those who knew her. I now try to merge her standards with her kindness and communicate my demands through humor. I learned that from her too.

The last time I saw Annie was after the Broadway in Bryant Park experience, at a restaurant across from the park. All I remember is eating cheese, drinking wine, sitting with Ann and the artistic team, and watching her heartily laugh and crack herself up over what, I don’t remember, as cast members shuffled in and out. She would gently take their hand and thank them, and go back to enjoying herself with the behind-the-table personnel who sat in plush chairs over dim candlelight in this night of post-theatre, low-key intellectual, and craftinspired reverie that only can happen in New York. May we all be remembered for such a beautiful legacy. I know her physical being is gone, but her spirit lives on in so many of us and the dancers she touched. Thank you, Annie, for all of it.

Jessica Redish is a director, writer, and choreographer.

PHOTO Jeff Vespa

TOP PHOTO by Rose Eichenbaum