27 minute read

Hot Topics

From Appreciation to Action

Maggie Reinbold, M.S., director of community engagement for San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, discusses ways to engage youth with wildlife conservation. “

The plain fact is that the planet does not need more successful people. But it does desperately need more peacemakers, healers, restorers, storytellers, and lovers of every kind. It needs people who live well in their places. It needs people of moral courage willing to join the fight to make the world habitable and humane.”

-DAVID ORR, PH.D., (AUTHOR, EDUCATOR, ENVIRONMENTALIST) FROM HIS BOOK EARTH IN MIND: ON EDUCATION, ENVIRONMENT, AND THE HUMAN PROSPECT

We all have a role to play in realizing Dr. Orr’s vision of a world of dedicated peacemakers. For more than a hundred years, SDZWA educators have inspired passion for nature through transformative wildlife experiences for visitors of all ages and from all over the world. These pivotal experiences unfold each and every day on grounds at the

Zoo and Safari Park, in our experiential learning labs at the Beckman Center for Conservation Research, and through our captivating publications and innovative digital content. Our work is to help visitors understand and appreciate the value of plants and animals, the inextricable link between wildlife and human well-being, and their own vital role in preserving wildlife into the future.

One critically important stakeholder group at the center of our efforts is local children, representing the next generation of regional professionals, voters, consumers, teachers, parents, and community leaders. Our founder, Dr. Harry Wegeforth, knew something of the importance of this stakeholder group when he dedicated the Zoo to the children of San Diego back in 1916. Every year since, we have engaged many thousands of local schoolchildren with experiential learning opportunities on grounds, in area schools, and in adjacent communities. These children, to whom the Zoo was dedicated, will soon be stewards of the most biologically diverse region in the contiguous United States—the California Floristic Province, our very own biodiversity hotspot—with its extraordinary array of habitats and endemic wildlife.

As we move into our second century of inspiring passion for nature, we deepen our

From Appreciation to Action

commitment to empowering local students with positive conservation actions to preserve the wildlife around them. For example, at the individual level, we are motivating students to save water on behalf of local endangered species, to conserve electricity to combat impacts of regional climate change, and to be thoughtful, responsible consumers of products and services. At the community level, we are inspiring them to petition their schools to adopt practices that support conservation, to organize cleanup events in their neighborhoods, and to lobby local governments in support of wildlife-friendly policies. And perhaps most importantly, we are encouraging them to share their knowledge and experiences with friends, family, and community members to inspire meaningful wildlife advocacy in others. Children transforming their knowledge and passion into positive conservation action offer enormous hope for the future. We see Dr. Orr’s vision come to life through student-inspired native gardens,

Youths represent the student-led wildlife awareness campaigns, student-analyzed wildlife monitoring data, next generation and through the impactof professionals, ful fulfillment of student voters, consumers, conservation pledges. Here teachers, parents, at the Alliance, we take on and leaders. this work with special honor, and we are more dedicated than ever to working alongside children to build a more habitable and humane world—a world where all life thrives. Young conservationists can explore nature at the Denny Sanford Wildlife Explorers Basecamp, opening soon.

The basics of nature play

Connecting youth with the natural world and inspiring future environmental champions

What:

Nature play is any activity that gets kids playing and learning in natural, outdoor spaces. It allows kids the freedom to move and explore, as well as to guide their own play decisions, stretch their imaginations, and develop a relationship with nature.

Where:

Any open-air space that offers opportunities to experience nature freely. Anywhere from a backyard or a neighborhood park to a trail, creek, or forest— the size and location of the space don’t matter, so long as kids have access to a diversity of tactile natural elements, such as vegetation, rocks, dirt, and water.

Why:

Kids are spending an increasing amount of time inside, engaging with screens and playing with artificial materials. It is more important than ever to encourage exercise of bodies and minds outdoors. The benefits of nature play are many: studies show that it enhances kids’ self-esteem, creativity, academic performance, social skills, and health. Further, it instills positive and long-lasting emotional connections to nature, environmental empathy, and pro-environmental behaviors— essential values for the future of conservation.

Well-grounded

Building a Future for Burrowing Owls

BY COLLEEN WISINSKI, M.S. | PHOTOS BY TAMMY SPRATT

One juvenile and two adult

burrowing owls survey their environment from just outside their burrow’s entrance.

magine Southern California with no freeways. Imagine the flat mesa tops with no houses, and open grassland for miles.

IAgainst that backdrop, western burrowing owls Athene cunicularia hypugaea were once widespread throughout the grasslands and coastal plains of San Diego County, but by the 2010s, there was only one breeding population left. Since 2011, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance has been working to halt the decline of this charismatic species through research and partnerships, and more recently, to increase their numbers through conservation breeding and translocation. We work to ensure that burrowing owls and other native species thrive, and aim to have a positive impact on wildlife right here in Southern California.

DID YOU KNOW?

When they want to, burrowing owls can cover huge distances. One was known to breed in Arizona and Canada—in the same year.

Whooo Are You?

The western burrowing owl is a grassland species that has been declining throughout its range in western North America for much of the past century due to changes in land use. This is particularly true in California, where ongoing urbanization and development of grasslands has led to loss and fragmentation of burrowing owl habitat, resulting in their current designation as a California Species of Special Concern. They also face reductions in habitat quality due to the proliferation of non-native grasses within the remaining grasslands of California. These tall, dense, non-native annual grasses (as opposed to more open native bunchgrasses) are not suitable for many native species without intense management like mowing or grazing, which require substantial financial and planning resources. In addition, the owls suffer from a loss of burrows due to removal of the fossorial (digging) animals they rely upon to create burrows. In San Diego County, California ground squirrels Otospermophilus beecheyi are the primary burrow engineers. However, California ground squirrels are also in decline, either through removal as a pest or from loss of habitat due to tall nonnative grasses. Even though burrowing owls can tolerate low to moderate levels of disturbance from human activities, they are increasingly affected by suburbanadapted predators, such as ravens, that can prey on both adult and juvenile owls, and greatly reduce nest success and productivity.

Collaboration— A Recipe for Success

Conservation work does not happen in a vacuum and often depends upon collaboration among many stakeholders. In San Diego, a countywide plan for conserving many different plant and animal species helps guide the efforts of government agencies, land managers, researchers, and conservationists. For the past 10 years,

our conservation science team has been part of a working group that includes land and wildlife managers, nonprofit organizations, and biological consultants, and helps guide our research and carry out conservation planning for burrowing owls within the county. The result of this coordinated effort is a better understanding of how we can conserve burrowing owls in the county (and beyond) and has allowed us to take bold actions to reverse the decline of this iconic species.

Conservation objectives for the burrowing owl population in the county include increasing the size of the population and spreading it out to more areas (what we call population “nodes”) as a sort of insurance policy. In order to accomplish this objective, two basic ingredients are needed: land and owls. This may sound straightforward but is certainly not simple. First, we need a sufficient amount of land with appropriate components such as food (invertebrates, small mammals, etc.) and shelter (burrows)—in short, habitat. And second, we need owls to move into that habitat.

The first ingredient is supplied by our partners. Over the past 10 years, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance and our working group collaborators have identified protected areas in the county that can provide owl habitat. Some of our partners, like the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and San Diego Habitat Conservancy, own and manage land for the purpose of providing protected habitat for native wildlife

Recovery ecology

staff perform finishing touches during the release at the second new population site.

DID YOU KNOW?

Burrowing owls don’t dig their own burrows; they depend on ground squirrels and other digging animals to create burrows. They often “timeshare” a burrow to incubate eggs and raise young during the owls’ breeding season.

for generations to come. We have worked closely with these entities to prepare their lands to receive owls. They use cattle grazing and mowing to keep the grasses short, and create cover piles made of rocks or brush to help the ground squirrels disperse into new areas, creating more burrows for the owls. Our partners have allowed us to install artificial burrows that are part of the translocation process, and conduct maintenance on these burrows annually.

With our expertise in wildlife care, conservation breeding, and reintroduction, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance is a natural fit to supply the second ingredient: owls. Sometimes, burrowing owls need to be moved out of harm’s way when land is being developed. In these situations, we often reintroduce owls from the development site to one of the protected areas identified as suitable for burrowing owls. But a small handful of owls impacted by development activities are brought into the San Diego Zoo Safari Park conservation breeding program, where they live for about two years. These owls usually raise one to two broods during their time in human care. Their offspring, and eventually they themselves, are released into protected areas to help bolster the burrowing owl population in the county.

A Bright Future on the Horizon

We are now in our fourth year of breeding and releasing owls into these protected areas. Using a soft-release method that includes an acclimation period, provision of important social cues via recordings of burrowing owl vocalizations, and supplemental food during the breeding season, we have met our early benchmarks for successful establishment of new population nodes. At our first release site, translocated owls have taken up residence and bred in multiple years following translocation, and they have even attracted some non-translocated owls to live and breed in the colony. We have observed multiple generations of owls pairing up and successfully raising their own chicks. This spring marked the first translocation to our second release site, and so far, those owls are meeting the same early benchmarks.

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance and our partners are committed to conserving the burrowing owl population in Southern California, so as you look out across those mesa tops, you don’t have to imagine a future without burrowing owls.

Colleen Wisinski, M.S., is conservation program manager in recovery ecology for SDZWA; Tammy Spratt is an SDZWA photographer.

An adult burrowing owl stands guard outside its burrow at the first new population release site.

Successful Hatchings at New Release Site

Following the reintroduction of 24 burrowing owls into our newly established release site in Ramona, California, SDZWA’s Burrowing Owl Recovery Program staff is excited to announce that the first owl chicks have hatched. Each chick gets weighed, measured, and fitted with leg bands that serve as unique identifiers. Twelve of the owls paired up and nested. Each pair reared offspring to fledging age, a major milestone for the collaborative effort to establish a new burrowing owl breeding node in the Ramona grasslands.

OH, TO BE UNDERS

DID YOU KNOW?

Desert tortoises spend about 98 percent of their lives sheltered underground in a burrow.

OH, TO BE UNDERS TOOD

The Plight of a Desert Icon and Efforts to Turn Things Around

BY RON SWAISGOOD, PH.D., MELISSA MERRICK, PH.D., AND TALI HAMMOND, PH.D.

Consider this: You are only about an inch high and very slow moving. You do have a hard outer shell, which is helpful at keeping some predators from eating you. Still, many predators think of you as a crunchy-on-the-outside, juicy-on-the-inside treat. What’s more, you live in a harsh desert environment, and are fortunate if you get a few drinks of water each year. You may have guessed by now that you are a desert tortoise. Getting “inside a tortoise’s KEN BOHN/SDZG shell” to understand its perspective on the world is a large part of what we do to try to better conserve this species.

DID YOU KNOW?

Tortoises do not have teeth; instead, they have a beak and grind their food.

Once common throughout the Mojave and Sonoran deserts

of California, Nevada, and Arizona, desert tortoise populations have declined approximately 90 percent in just the last 20 years.

Off to a Good Headstart

Several years ago, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance began a program to understand tortoise habitat needs and develop best practices for rearing and releasing tortoises back to the wild, in areas where their future can be safeguarded. We conduct this work with a number of important partners, including the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Edwards Air Force Base, and others.

In our desert tortoise conservation program, we use headstarting and translocation as tools for species recovery. The process starts out with a search for tortoise momsto-be. We search the desert for adult female tortoises, give them small transmitters for tracking purposes, and using a mobile X-ray unit, periodically check to see if they are gravid (that is, have eggs). When they are gravid, we bring them into headstarting facilities to lay eggs for headstarting. We then return females to where they were found but keep the eggs (and eventually hatchlings) safe in our protected facility, where predators cannot reach them, and food is plentiful. They thrive here, but after one to two years, these young tortoises reach sufficient size to be less vulnerable, and the time comes for them to return to the wilderness, where they can help reestablish their species.

Trouble in the West

The Mojave desert tortoise Gopherus agassizii is one of the most beloved denizens of the western deserts of the US. Yet, despite the vastness of the American desert, the situation for the tortoise is becoming increasingly desperate: each passing year there are fewer and fewer of them to be found. It seems to be a case of “death by a thousand paper cuts,” with numerous human actions eroding away at tortoise habitat: roads, solar developments, and an increase of “subsidized” predators. Subsidized predators are predator species that thrive in urbanized or human-associated habitats thanks to their ability to take advantage of resources that are associated with humans. In the deserts of the southwestern US, ravens are considered “subsidized predators” and are much more numerous today than they were historically, which is a big problem for desert tortoises.

A Tortoise-eye View

It’s a heartwarming experience to watch these tiny tortoises experience their natural desert landscape for the first time, with its whimsical Joshua trees peppering bright blue desert skies, and miles and miles of sand. But the real work comes in monitoring these animals and understanding how they use their new, wild habitat. Our work focuses on ecological factors that help make young tortoises less vulnerable to predators, such as refuge and camouflage. A two-year-old tortoise is still no match for a raven, and its main defense is to remain undetected.

This is where understanding the tortoise’s perspectives comes in: we hypothesized that camouflage, in the form of rocky ground (tortoises look rather like rocks), or burrows (constructed by small mammals) that serve as refuges from predators (and inclement weather) could be vitally important to avoid ending up as a meal for a raven or some other hun-

gry predator. We also know that all desert environments are not equal, and some contain different compositions of plant species that might afford food or shelter.

Armed with these ideas, we set out to test how careful selection of release site might affect tortoise health, growth, movement, and survival. Does camouflage, refuge availability, or plant community make a difference? In our first round of tests, conducted in Nevada and led by Melia Nafus, Ph.D., (working for SDZWA at the time, but now with USGS), the answer was an unqualified “Yes.” Careful site selection based on these factors boosted one-year survival from 20 percent to almost 80 percent! However, the Nevada and California deserts can be quite different, and the next step was to determine whether these same benefits still hold true in California. In scientific parlance, we wanted to know whether our findings were generalizable.

Today, we are in the midst of this second round of efforts. We raised nearly 150 healthy young tortoises and released them into several sites within Edwards Air Force Base and Ward Valley, managed by the Bureau of Land Management. We do not yet have answers from this more recent study, but we are actively tracking these tortoises to monitor how they are doing. We also conduct periodic health assessments and measure growth rates to determine which tortoises are thriving, data that in turn inform us about habitat quality. We predict that tortoises will grow faster in higher quality habitat.

Looking Ahead—and Up

It is our hope that, in addition to replenishing declining populations of this desert icon, our research will help us learn more about tortoise habitat needs. The knowledge gap about young tortoises is especially large, in part due to difficulties in finding them. They spend about 98 percent of their lives below ground, sheltered in a burrow, coming up following rains to eat and drink. Mystery has never informed conservation action, so our aim is to make the lives of young tortoises less mysterious. While we know what constitutes “suitable habitat,” we don’t know what makes “great” habitat, which allows tortoises to thrive, not just survive. This knowledge will help conservation managers make better decisions about where to release tortoises that need to be translocated, which habitat areas to prioritize for protection, and which features of the environment are important to restore to improve existing tortoise habitat. Armed with this knowledge, we plan to promote the recovery of this beloved species of the Mojave Desert of California.

A female desert tortoise can retain sperm and lay fertile eggs for up to 15 years after mating only one time with a male. This project was made possible by generous support from the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, the California Energy Commission, the National Fish & Wildlife Foundation, Edwards Air Force Base, the Favrot Fund, and the Zuest Family Foundation.

Ron Swaisgood, Ph.D., is the recovery ecology director for SDZWA; Melissa Merrick, Ph.D., is a recovery ecology associate director for SDZWA; Tali Hammond, Ph.D., is a recovery ecology scientist for SDZWA.

Close Encounters

10 ways the Zoo’s all-new experience—opening soon—inspires both passion and empathy for nature in explorers of all ages.

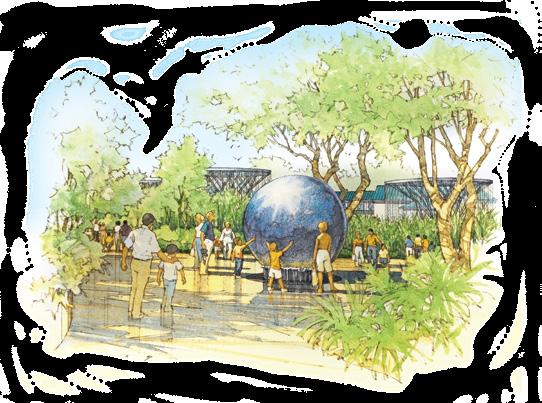

Conservation is first and foremost about people. And inspiring the next generation of wildlife allies to join us in creating a world where all life thrives is the driving force behind the new Denny Sanford Wildlife Explorers Basecamp, a re-imagining of the former Children’s Zoo, opening soon. It’s the most significant expansion in the Zoo’s history, and it’s filled with immersive experiences, curious encounters, and engaging surprises around every corner. From naked mole-rats to coconut crabs, rainforests to desert dunes, it’s a truly inspiring celebration of nature and wildlife.

You might spot one of the San Diego Zoo Rady Ambassadors—furry, feathered, and scaly friends who take part in voluntary up-close encounters with visitors—in their dynamic new habitats here. But their homes might also be empty. If that’s the case, the ambassadors (like Manny the tamandua) are likely meeting visitors out and about on Zoo grounds. Or, they might be visiting a retirement facility or children’s hospital. These wild face-to-face meetings can be a powerful catalyst for 1 conservation learning, so keep an eye out. You never know who will be right around the corner!

EXPERIENCE IT Visit sandiegozoo.org to learn more and get tickets.

AMY BLANDFORD/SDZWA 2

Empathy Workout

Empathy, or the ability to understand the feelings of another, is like a muscle; the more you use it, the stronger it gets. The Zoo’s new experience for children was designed to help visitors build empathy for wildlife, especially the so-called “creepy crawlies” that rarely get much love, in order to cultivate the next generation of wildlife protectors. This means that with each visit, people will leave with more compassion for creatures great and small. Increased empathy for wildlife has also been linked to increased empathy for people—the same parts of the brain are activated—so we hope that visitors will leave with greater care for each other, as well.

Parents and caregivers play a critical role in helping children develop empathy. By modeling positive encounters with wildlife, you set the foundation for lifelong wildlife advocates to grow. Families can continue to strengthen their empathy muscles even after leaving this new experience at the Zoo, by taking home a children’s book by award-winning San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance author Georgeanne Irvine. Each story tells a unique tale of hope and inspiration, allowing children to forge strong connections with the animals featured.

KEN BOHN/SDZWA

3Give a Hoot At just 10 inches (or two soda cans) tall, burrowing owls are one of our smallest neighbors in the Southwest—and in danger of becoming locally extinct. San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance collaborates with partners to protect burrowing owls through our Southwest conservation hub. Some chicks hatched in our care are reintroduced to their native habitat in San Diego County. Come face-to-beak with these raptors during your visit.

AMY BLANDFORD/SDZWA

4

What’s the Buzz?

Inside the McKinney Family Spineless Marvels invertebrate house, you can peer inside a hive and marvel at thousands of honeybees hard at work—and maybe talk to a beekeeper. Honeybees were introduced here by European colonists in the 1600s, but long before they arrived, native bees were doing the pollinating. A mural near the honeybee habitat tells their story. Native bees don’t make honey, and they don’t live in hives. In fact, native bees are mostly solitary. There are at least 20,000 species of these bees, on every continent except Antarctica—and more than 4,000 of them in North America.

5

Nature Play,

All Day Who knew fun could be such serious business? At this new experience for children, kids can splash, slide, and jump side-by-side with wildlife. But these water features and climbing structures have a hidden benefit: time playing in and around nature has been shown to boost the physical, cognitive, social, and emotional aspects of children’s development. Nature play gives kids the opportunity to play freely in natural settings, with limited structure imposed by adults, building self-confidence, resilience, and creativity. We hope that swinging with monkeys and sliding by prairie dogs inspires people of all ages to continue enjoying time in nature, even after you’ve left the Zoo’s front doors.

No Glass? No Problem

6

KEN BOHN/SDZWA

You might notice something missing from the golden orb weaver habitat: a barrier separating you and the spiders! But arachnophobes, have no fear. Golden orb weavers live life vertically, staying put in their strong, stretchy webs as long as they have everything they need. San Diego Zoo wildlife care specialists make sure that the orb weavers have insects to eat, water droplets to drink, and plenty of branches to weave their three-foot-wide webs, creating a safe and comfortable spider home. This means there’s no need for the golden orb weavers to wander—and no need for you to run away.

Be a Mole-rat And see what life is like in their tunnels. Like ants and honeybees, these unusual rodents are eusocial. One queen is the mother of almost all the other molerats, and everyone in the colony has a job—like gathering food, digging 7 tunnels, defending the burrow, or caring for young. Nearby, a kid-size tunnel immerses children into the sights, sounds—and even smells—of molerat life, and brings them face-to-face with a…kid-size mole-rat!

GLOBALP/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

8

Save Fijian Iguanas

They don’t fly or breathe fire. But brightly colored Fijian iguanas do look like tiny, scaly creatures from a fanciful medieval legend. It’s no wonder one researcher described these endangered iguanas as resembling “neon-colored dragons.” But invasive species such as feral cats, rats, cane toads, and mongooses prey on them. They are losing habitat, and some are taken for an illegal, international exotic pet trade. Thankfully, your support of SDZWA helps these endangered lizards.

Kim Gray, curator of herpetology and ichthyology at the Zoo, participates in research in Fiji with partners including the U.S. Geological Survey, Australia’s Taronga Zoo, and the National Trust of Fiji. We’re also helping the people of Fiji to raise hatchlings until they are large enough to avoid predators (a process known as “headstarting”). Meet the neon dragons in the Art and Danielle Engel Cool Critters herptile house. With more than 125 young hatched here since 1981, we have the most successful breeding colony outside Fiji.

9

Tech? Check.

We’ve integrated dozens of handson ways for technology to enhance your experience at the new Denny Sanford Wildlife Explorers Basecamp. Will you be able to find the animated stick insects on our interactive screen? Give it a try! While you’re here, check out the multiuser microscope stations— embedded touch displays and software allow you to examine objects up close, take a snapshot, add notes and drawings, and share your observations. Volunteers and wildlife care specialists will be able to share multimedia as they interact with guests, thanks to custom touch tables that double as game consoles to help you learn more about conservation. Watch time-lapse images of orb-weaver spiders building webs, and visit our “underground” ant colony, illuminated by black light. You’ll also wander through an immersive migration experience, with surround sound, a meadow smellscape, and migrating butterflies and dragonflies “flying” above you, projected across a domed ceiling.

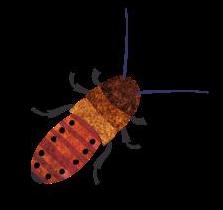

Who’s Doing the Dirty Work? What happens to dead plant and animal matter before it decomposes? Meet the heroes of recycling. Cockroaches, millipedes, and beetle larvae—called grubs— munch stuff that might seem disgusting to us. But their food preferences are an important part of the nutrient cycle. By breaking this gunky material into small pieces (and pooping it out), they make it available to protozoans and bacteria that decompose it into molecules we need for life. From giant African millipedes to question mark roaches and enormous goliath beetles, they do their part, and you can see them in the McKinney Family Spineless Marvels invertebrate house.10

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance & APMEX

Penguins and Rhinos Commemorated in Silver

Visit APMEX.com/SDZWA to collect them all.

Don’t let all that walking get the best of you!

Stay fueled up by visiting one of our branded concessions. The San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park thank our partners for their continued support!

California Floristic Province Madrean pine–oak woodlands

North American Coastal Plain

36 Global Biodiversity Hotspots

Mediterranean Basin

PolynesiaMicronesia Mesoamerica

Tumbes–Chocó–Magdalena Caribbean Islands

Tropical Andes

Cerrado

Chilean Winter RainfallValdivian Forests

25%of all known ocean species are supported

by coral reefs. Though they are some of the most biodiverse marine ecosystems, coral reefs represent less than 1% of the Earth’s oceans.

Atlantic Forest Guinean Forests of West Africa Eastern Afromontane

20%

of all vascular plant, 13% of all amphibian, and 17% of all bird species on the planet can be found in Brazil—making it one of the world’s most biodiverse countries.

Coastal Forests of Eastern Africa

Succulent Karoo

Cape Floristic Region MaputalandPondolandAlbany

Biodiversity Hotspots

The most biologically rich—and endangered—regions on Earth

Biodiversity hotspots host an exceptional variety of endemic life: these unique regions are teeming with species that can’t be found anywhere else on Earth. However, hotspots are also exceptionally threatened. To be classified as a hotspot, a region must have at least 1,500 species of endemic vascular plants and must have lost at least 70% of its native vegetation.

By Elyan Shor, Ph.D.

Mountains of Central Asia

Mountains of Southwest China

IranoAnatolian

Eastern Himalaya

Western Ghats and Sri Lanka Horn of Africa IndoBurma Philippines Japan

PolynesiaMicronesia

>50%

of the hotspots are in the tropics. Southeast Asia alone accounts for up to 25% of all plant and animal species on Earth.

Madagascar and the Indian Ocean Islands Sundaland Wallacea

Eastern Australian temperate forests East Melanesian Islands

New Caledonia

Southwest Australia

New Zealand

Biodiversity hotspots affect the well-being of the whole planet.

They provide up to 35% of the world’s ecosystem services—including fresh air, clean water, food sources, and climate regulation. The health of wildlife, people, and ecosystems are deeply interconnected: we need biodiversity so that all life can thrive.

world

land surface

world

mammal, reptile, bird, fish, amphibian, and plant species

world

ecosystem services

biodiversity hotspots biodiversity hotspots biodiversity hotspots

Biodiversity in our own backyard! San Diego is:

1. In the California Floristic Province

This hotspot extends from northern Baja California to southwestern Oregon. Over 2,500 of the vascular plant types here cannot be found anywhere else on Earth.

2. Highly biodiverse

San Diego is the most biodiverse county in the continental United States. It is home to 26 endemic, 139 rare, and 14 endangered vascular plant types.

3. A unique collection of habitats

From beaches to forests, to mountains, scrublands, marshes, and deserts, this broad array of ecosystems makes San Diego remarkably rich in wildlife.

3. Home to rare wildlife

The burrowing owl, Peninsular bighorn sheep, Quino checkerspot butterfly, and desert tortoise are some of the many native animals found locally.

5. Threatened with habitat loss

As the main habitat in Southern California, coastal sage scrub once covered much of San Diego. Today, only 10% of the habitat remains, with wildfires and urban expansion among the major drivers of habitat loss.