ISSUE 2, 2023 TheConservationandHealth oftheCentralPacificOcean

SEA Writer

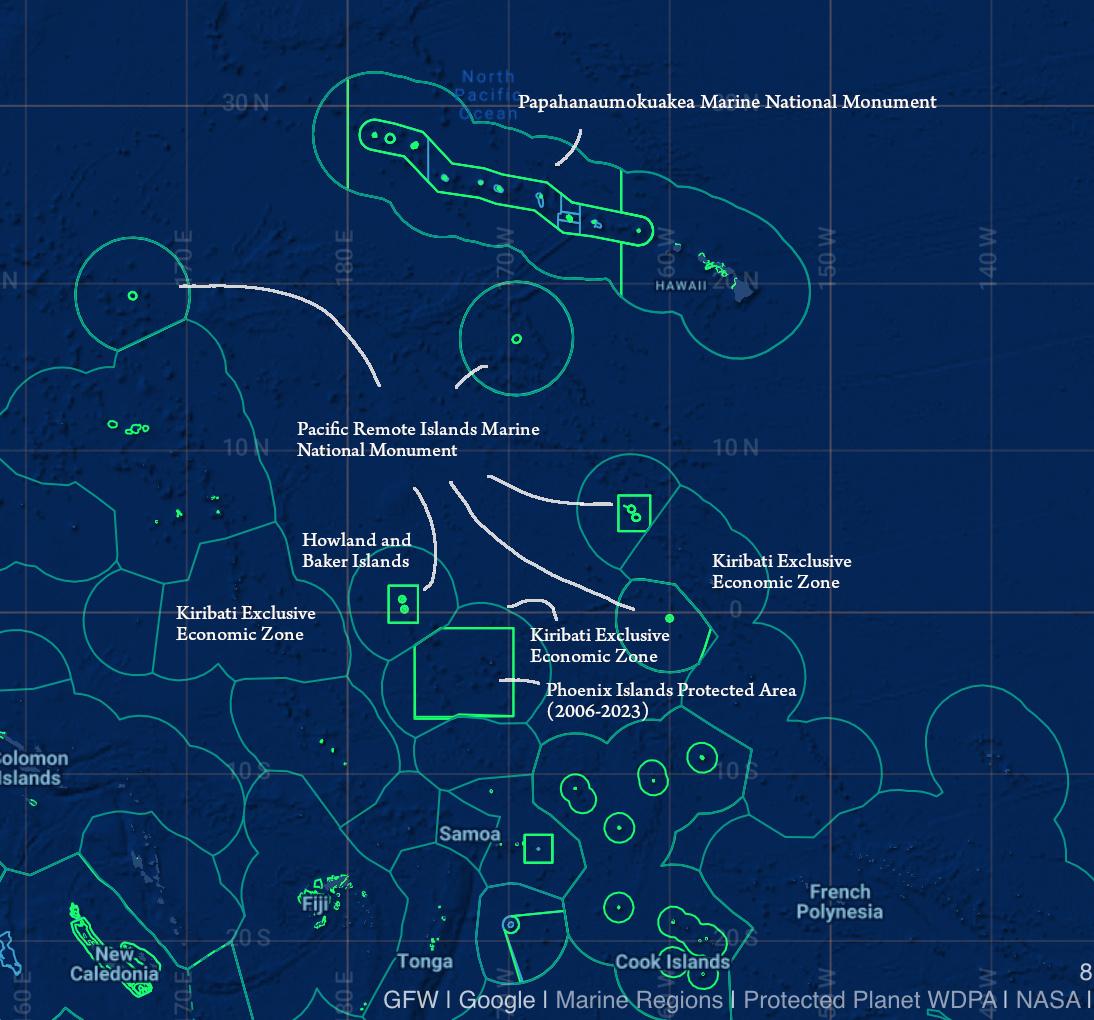

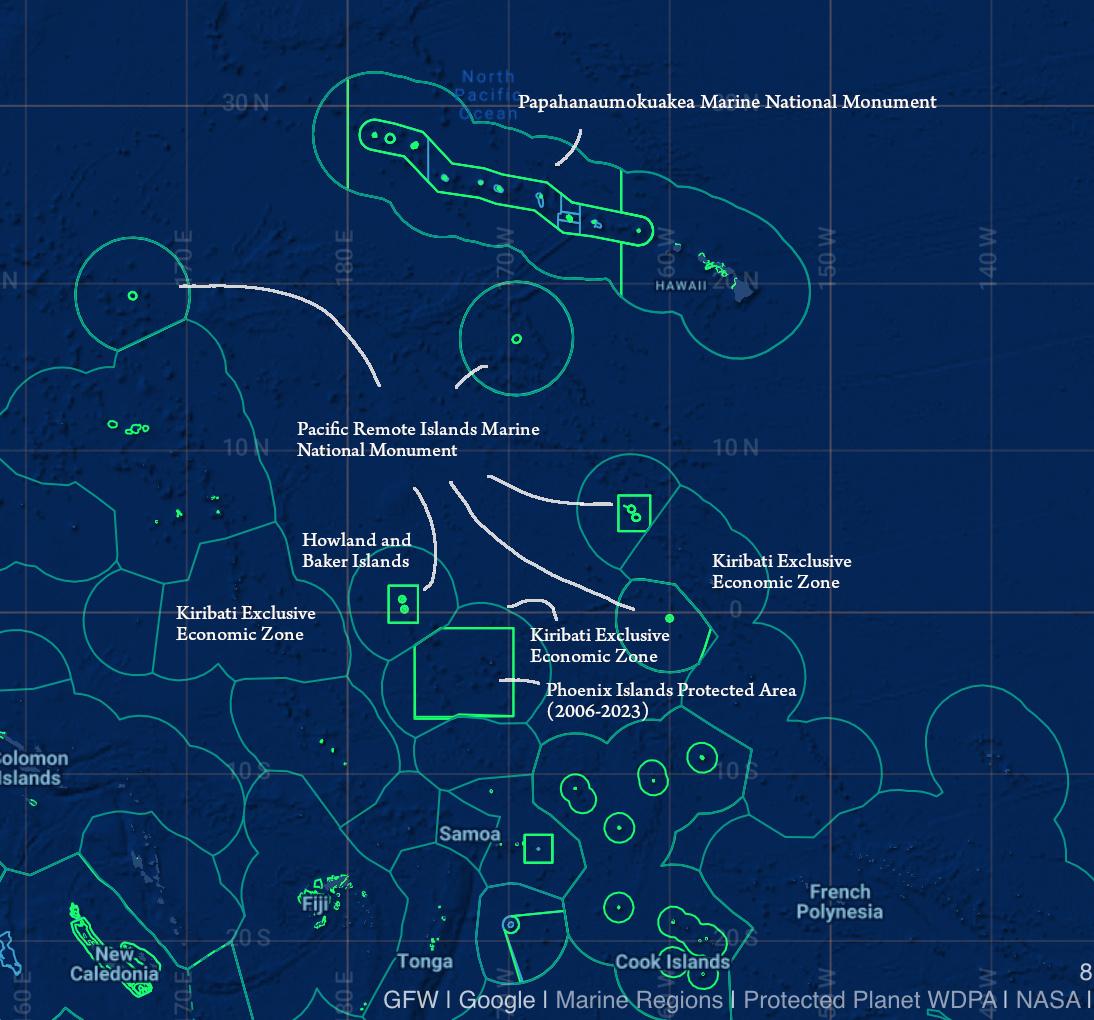

Light green=Exclusive Economic Zone (200 nautical miles from coast)

Bright green=Marine Protected Areas

Map adapted from Global Fishing Watch

- -

Introduction

S’310 Mission and Ethics Statement

“Oceanographic Overview”

"A Passage Through the Torrid Zone”

"Carbon Dioxide Fugacity and Ocean Acidification: A Silent but Deadly Threat"

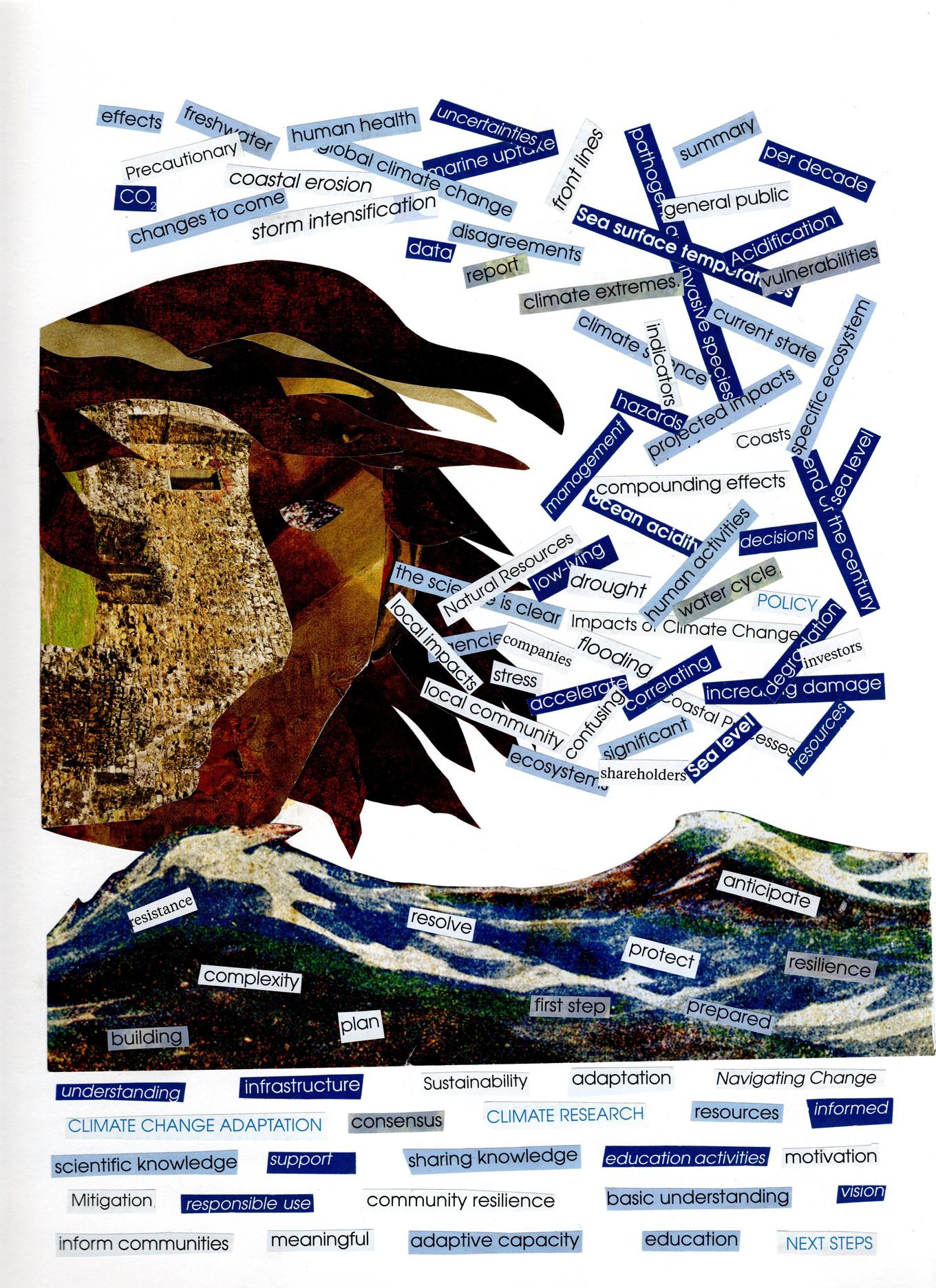

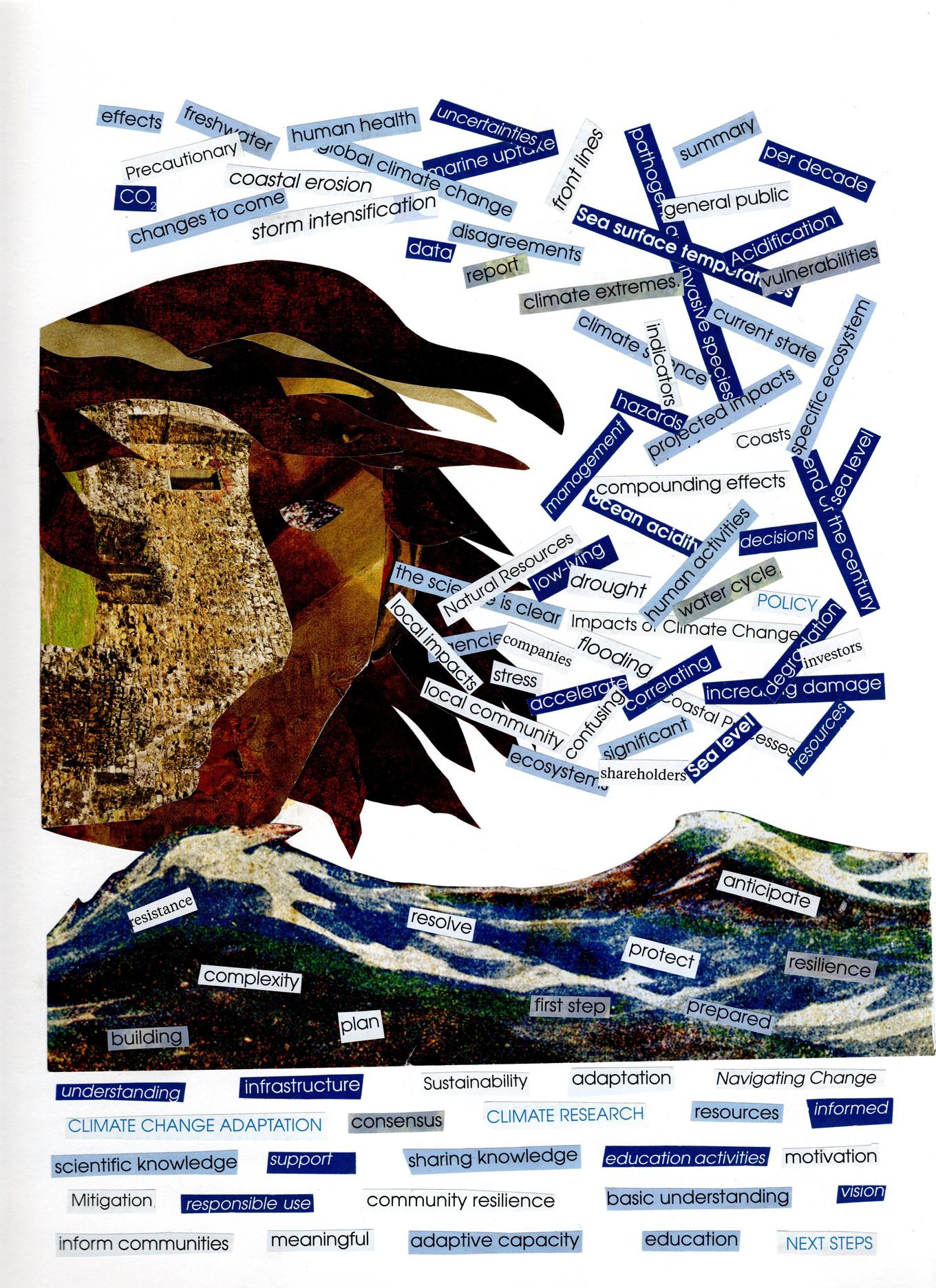

"Teaching Climate Change in the Midst of Catastrophe"

"Who Holds the Steer?"

"The Forgotten Realm’s Dilemma: Deep Sea Mining"

"Energizing the Pacific Islands"

"Shifting Blue"

"Beyond the Goop: Tuna Larvae and the Pursuit of Sustainable Fishing"

"If I Were a Fish, My Dying Wish: You’d Count Me"

"The Shark Unfinned: That State of Global Shark Populations"

"Connecting New England to the Pacific through Sperm Whales"

“Seabirds in the Central Pacific”

"Life Lessons from a Booby"

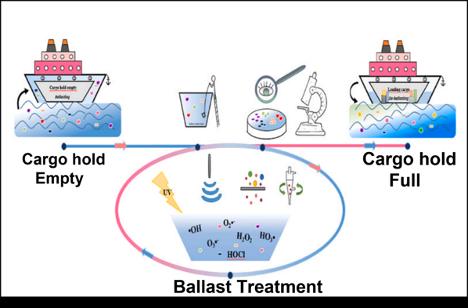

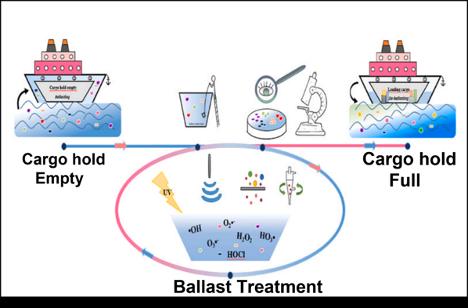

"How to treat Marine Invasive Species like a Doctor"

"Plastic in the Pacific: From the Depths of the Ocean to Shores Seen By A Few"

"What We Can Do about the Health of the Central Pacific Ocean?"

Contents

Coda Biographies Voyage Map 4–6 7–8 9–10 11–14 16–20 22–28 29–34 36–40 42–46 48–50 52–56 58–61 63–67 69–73 74–77 78–81 83–88 90–92 93 94–95 96–98 99

The Sea Education Association (SEA), based in Woods Hole, MA, USA, offers ocean studies programs for undergraduate, gap year, and high school students

Introduction

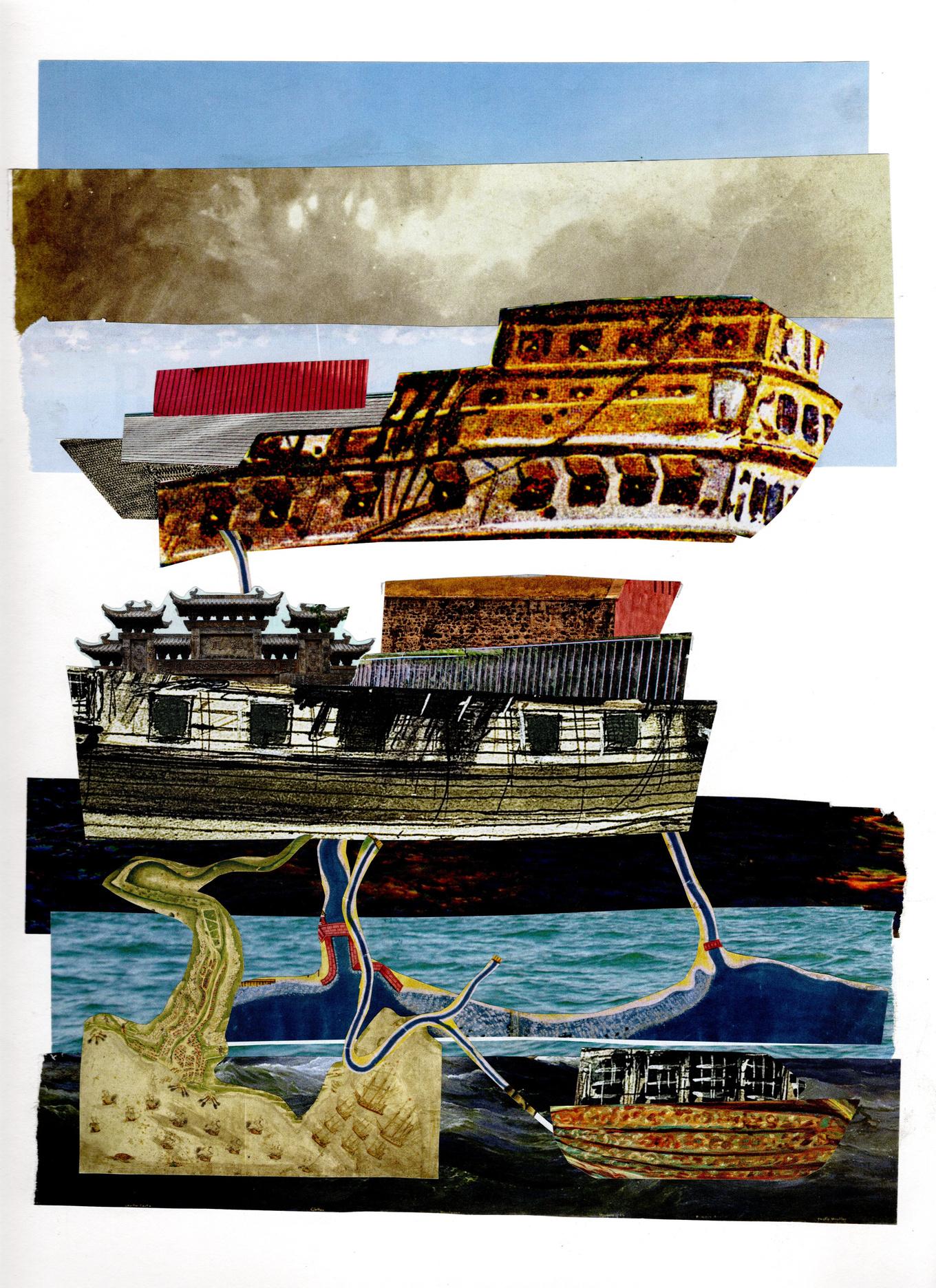

On the 7th of June 2023, only the second full day in Woods Hole for the students of class S’310, the Ambassador to the United States from the Republic of Kiribati walked into the classroom. Although Mr. Teburoro Tito, who was also the former president of Kiribati, was wearing a tie and jacket, his demeanor and tone put the students immediately at ease. The meeting felt more like “a hang-out with a distant relative,” as student Sam Barresi put it. Ambassador Tito sang traditional songs from Kiribati but also had a sing along with a John Denver tune Student Julius Gabelberger presented him with a signed homemade card from everyone, adorned with a painting of a frigatebird, the national bird of his country, and before he was whisked off for various other tours around the campus and on board one of SEA’s ships, the Ambassador managed to make us all feel that our oceanographic research was important and useful that the voyage ahead had a meaning larger than ourselves

We were spending three weeks in Woods Hole in preparation for a six-week voyage at sea. The students met the SSV Robert C. Seamans in Honolulu, where aboard was a full staff of scientists, visiting scientists, watch officers, deckhands, and other academic and professional maritime crewmembers, totalling thirty-three people.

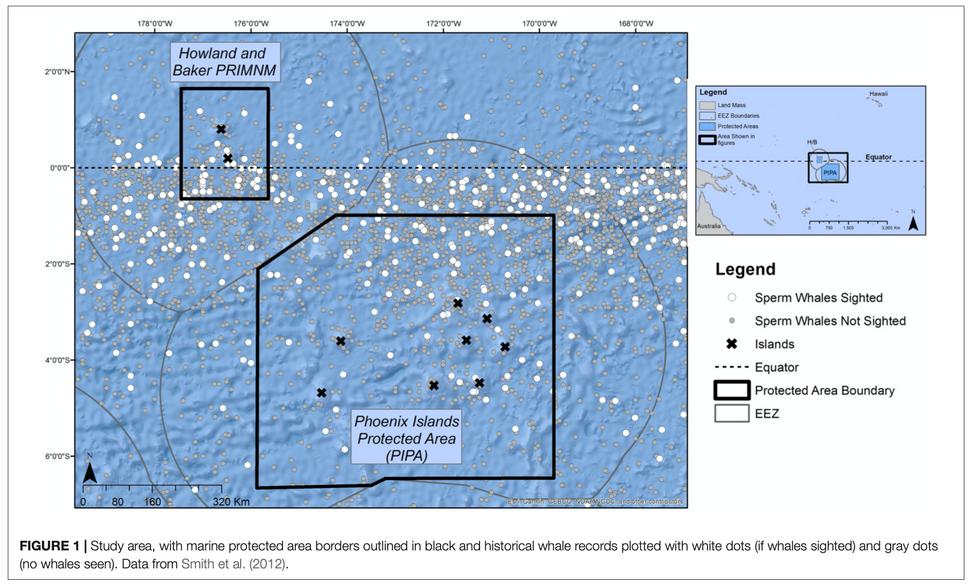

The plan had been to visit the Phoenix Islands Marine Protected

ISSUE 2, 2023 cont'd >

Area (PIPA), where we hoped to continue our baseline research oceanographic and ecological conditions, just as we had done nearly every summer since 2014, sending our data to the PIPA office in Tarawa and to other partners. But by the time Ambassador Tito came to Woods Hole, we all knew that PIPA was no longer a marine reserve Political winds and financial needs had shifted back home. Fishing vessels had been let back into the region.

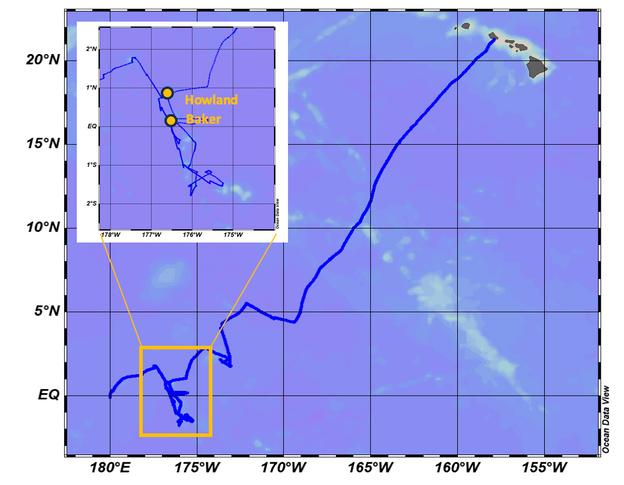

To a new department in the government of Kiribati, SEA had entered a new permit to request permission to conduct research. This permit still active even as we left the dock and began sailing south from Oahu, but in the end we could not get an observer on board in time, so we changed our cruise track to go just to the north, to the marine protected area that borders PIPA, the portion of the Remote Pacific Islands Marine National Monument (PRIMNM) that extends out from Howland and Baker Islands The PRIMNM was first established in 2009, then expanded in 2014. This portion of the PRIMNM is managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, who gave us permission to sample within the monument’s waters, up to three miles from the shore of these tiny islands, these low tips of sea mounts that tumble steeply down more than 3,000 meters beneath the surface.

Though we were disappointed to

not visit the waters of Kiribati and meet the people stationed on Kanton Island, the waters around Howland and Baker, known as the American Phoenix Islands, are no less fascinating oceanographically, historically, and in terms of current management. This region offers data on the characteristics of marine protected area waters around equatorial sea mounts. And we knew we were learning in real time about geopolitical interactions with marine conservation. We respect the sovereignty and goals of Kiribati, a relatively new government, regaining independence in 1979 a nation whose territorial waters stretch across the equator a similar distance to the width of the United States.

So we sailed and sampled in US waters, sweated below, hauled on lines, cooked, cleaned, and sweat some more under the equatorial sun. As we sailed south toward Fiji, we analyzed our data, and after five weeks and over 4, 200 miles, we dropped our anchor off Savusavu Harbor in Fiji.

Throughout the trip, we continued our efforts to learn about the oceanographic and ecological health of the central Pacific Ocean, the current management of these waters, and about the people who have lived and moved through these vast waters for well over a thousand years Kiribati, along with several other low-lying nations in the Pacific and other parts of the world, are on the very front lines of climate change.

cont'd >

Although the I-Kiribati people had nothing to do with the creation of the problem, global warming is currently killing their reefs and sea level rise is inundating their shores and spoiling their already scant freshwater resources.

This magazine, this special issue of SEA Writer, focuses on the health and management of the Central Pacific This issue is an interdisciplinary reflection of some of our studies, both on shore and at sea.

Ambassador Tito told us that “Any human-made mess must have a human made fix.” If he can stay positive and keep working, we can, too.

On Monday July 31st, a rainy afternoon hundreds of miles from any land, we gathered in the salon of the Robert C Seamans and tried to build consensus on what we could do the result of which is at the end of the magazine.

We thank you for reading.

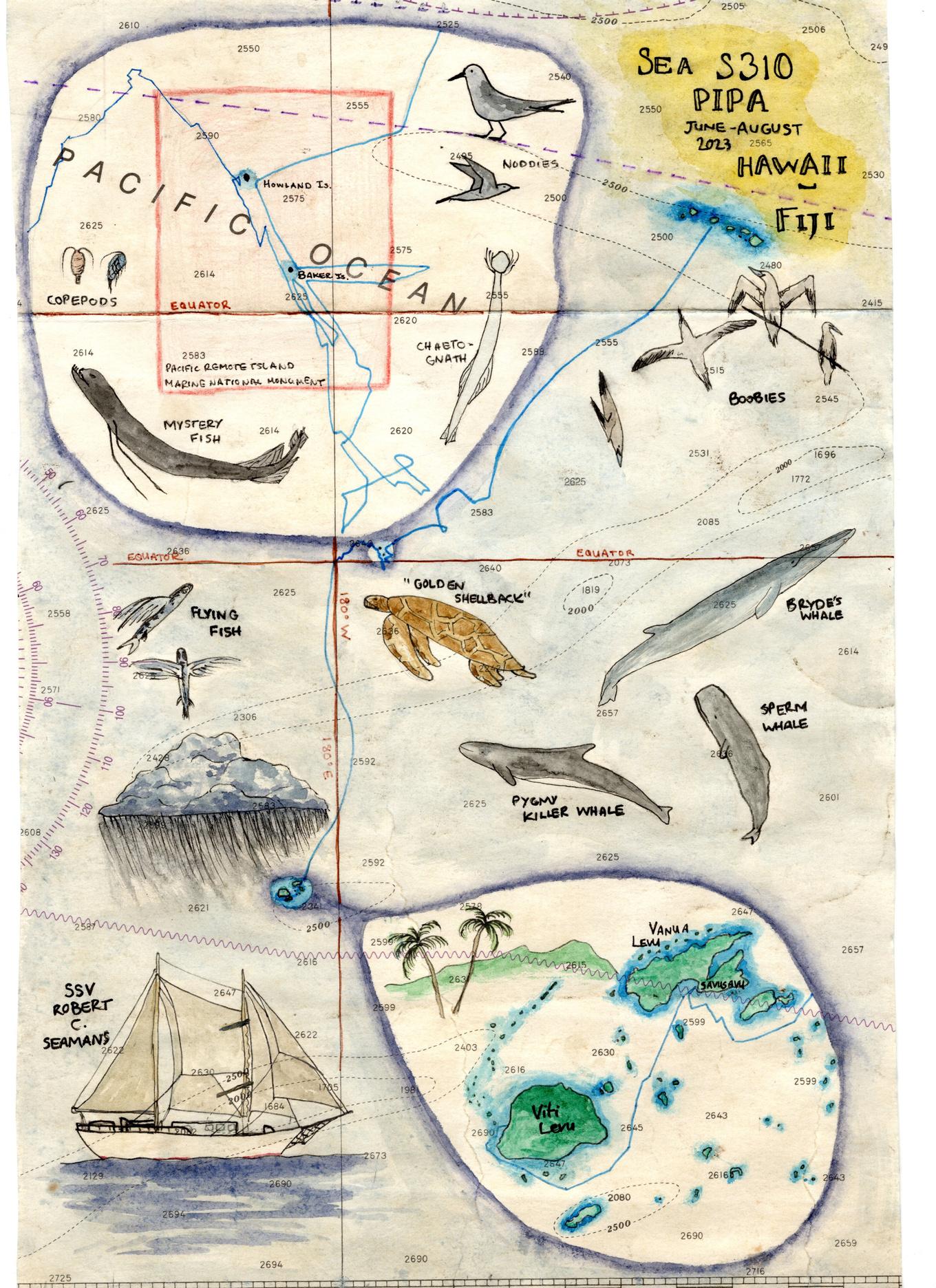

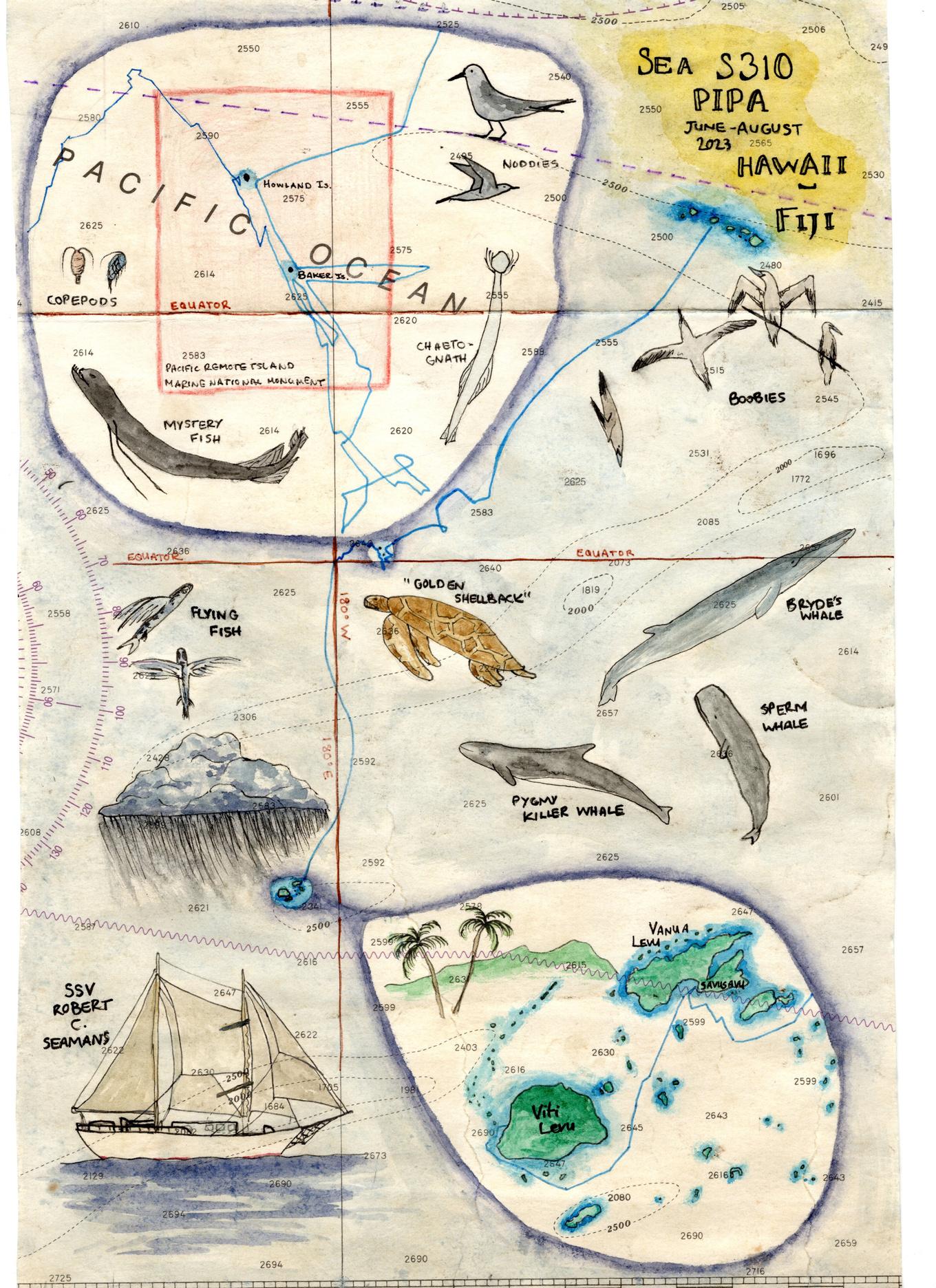

This summer's SEA Semester, class S'310, aboard the SSV Robert C. Seamans involved three weeks of preparation in Woods Hole, MA, then a six week sail from Hawai'i to Fiji via the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument. Undergraduate students took classes in 'Oceanography' and 'Conservation and Management.'

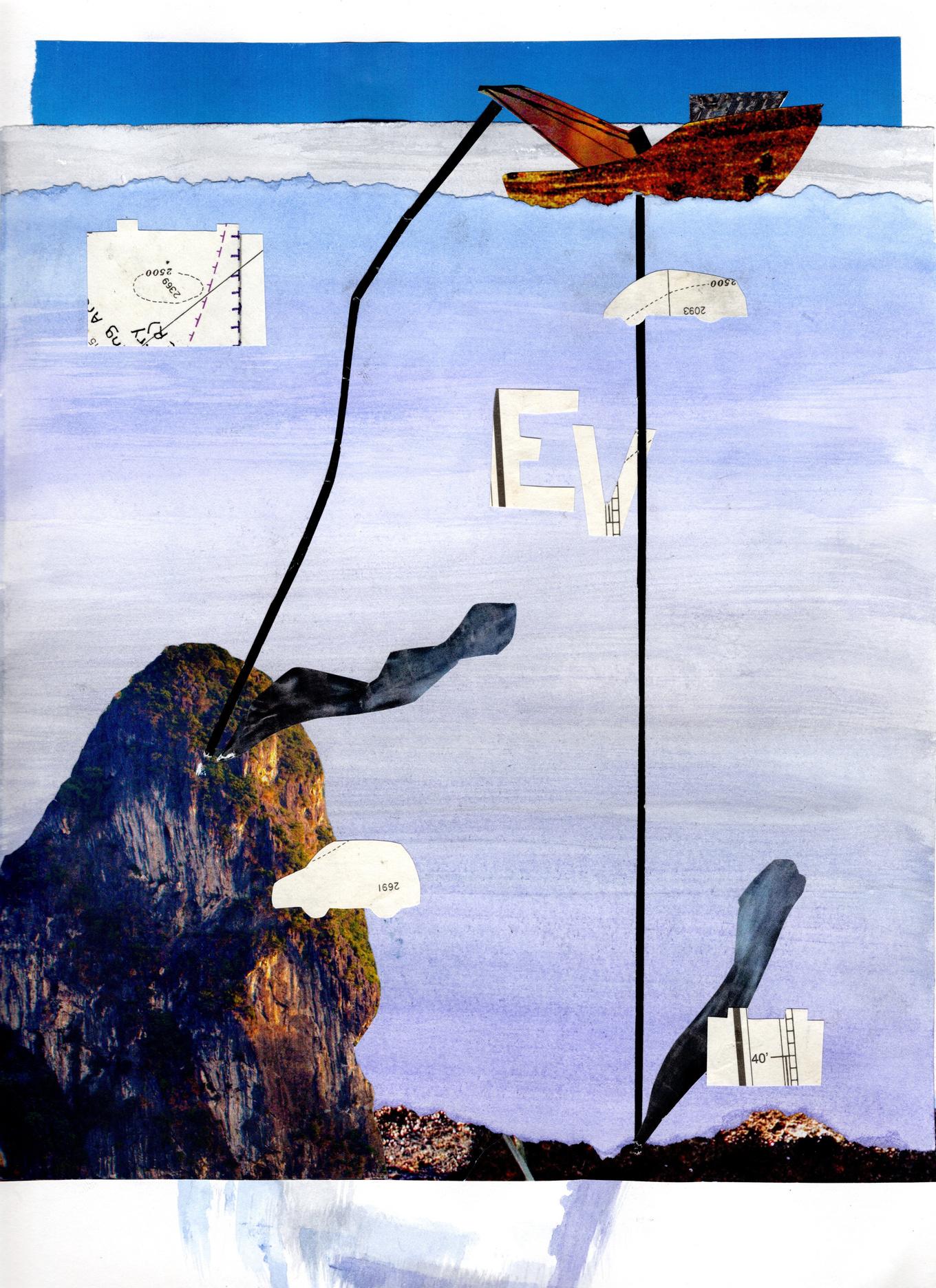

Cover art: Julius Gabelberger

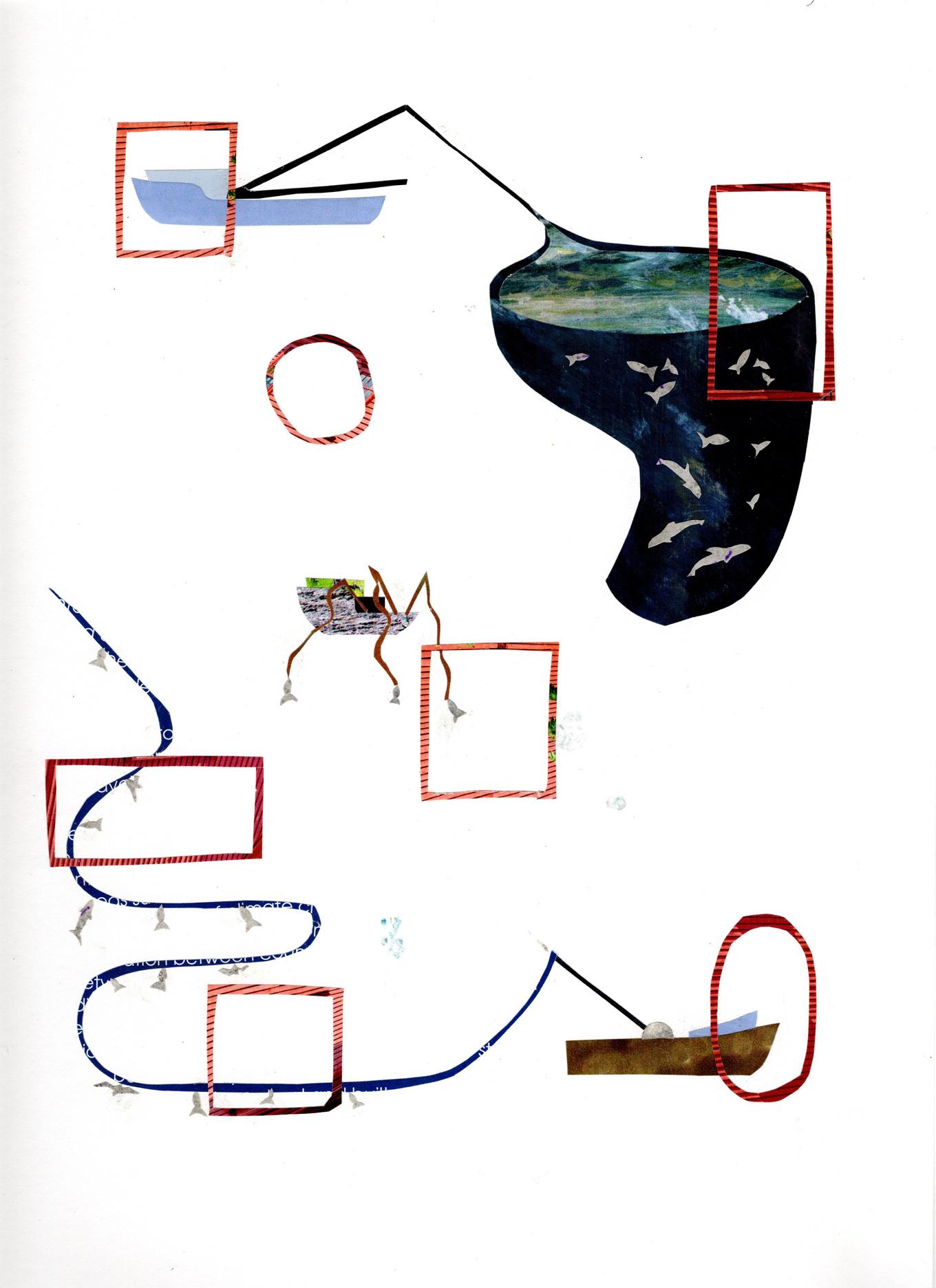

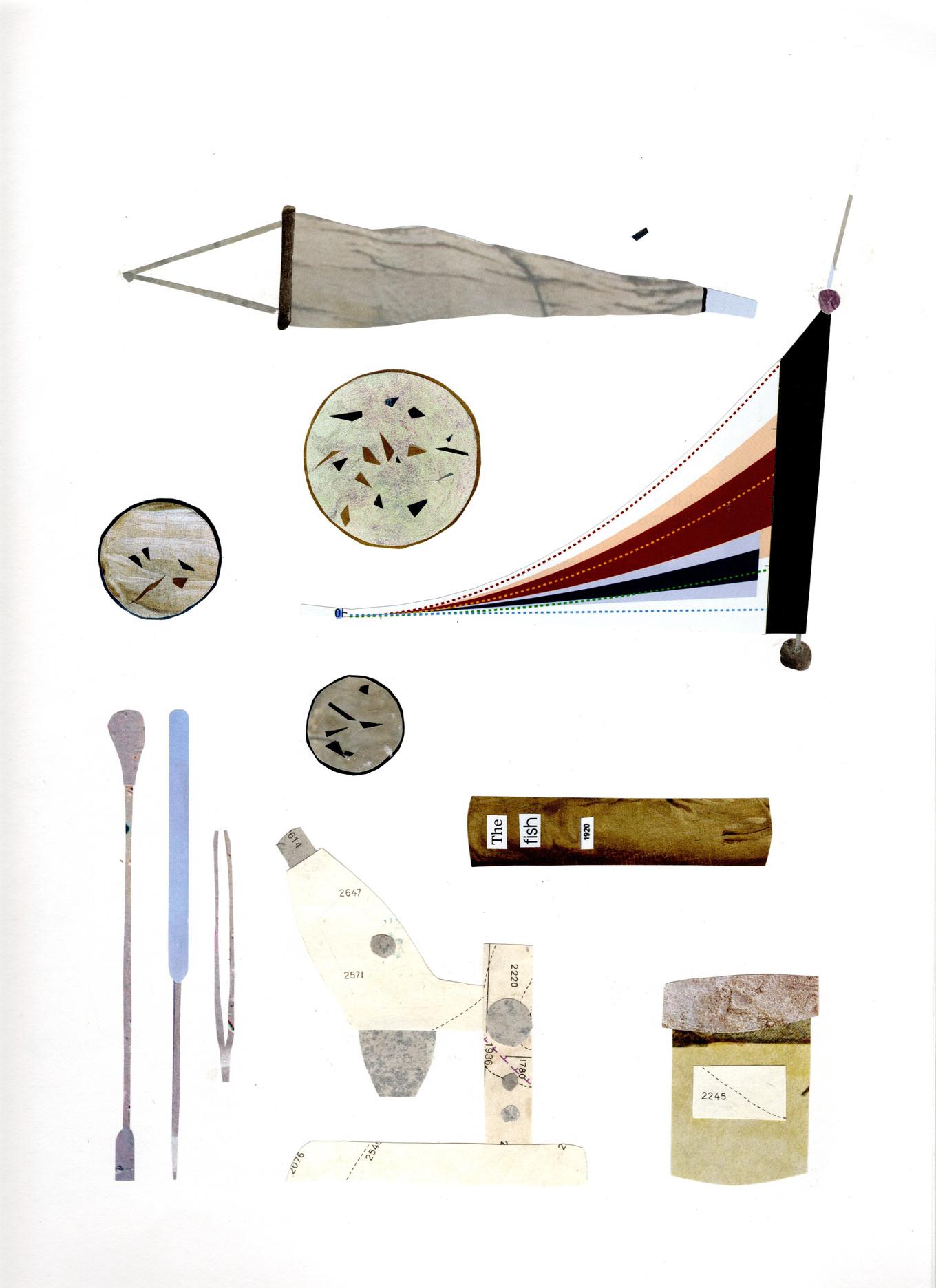

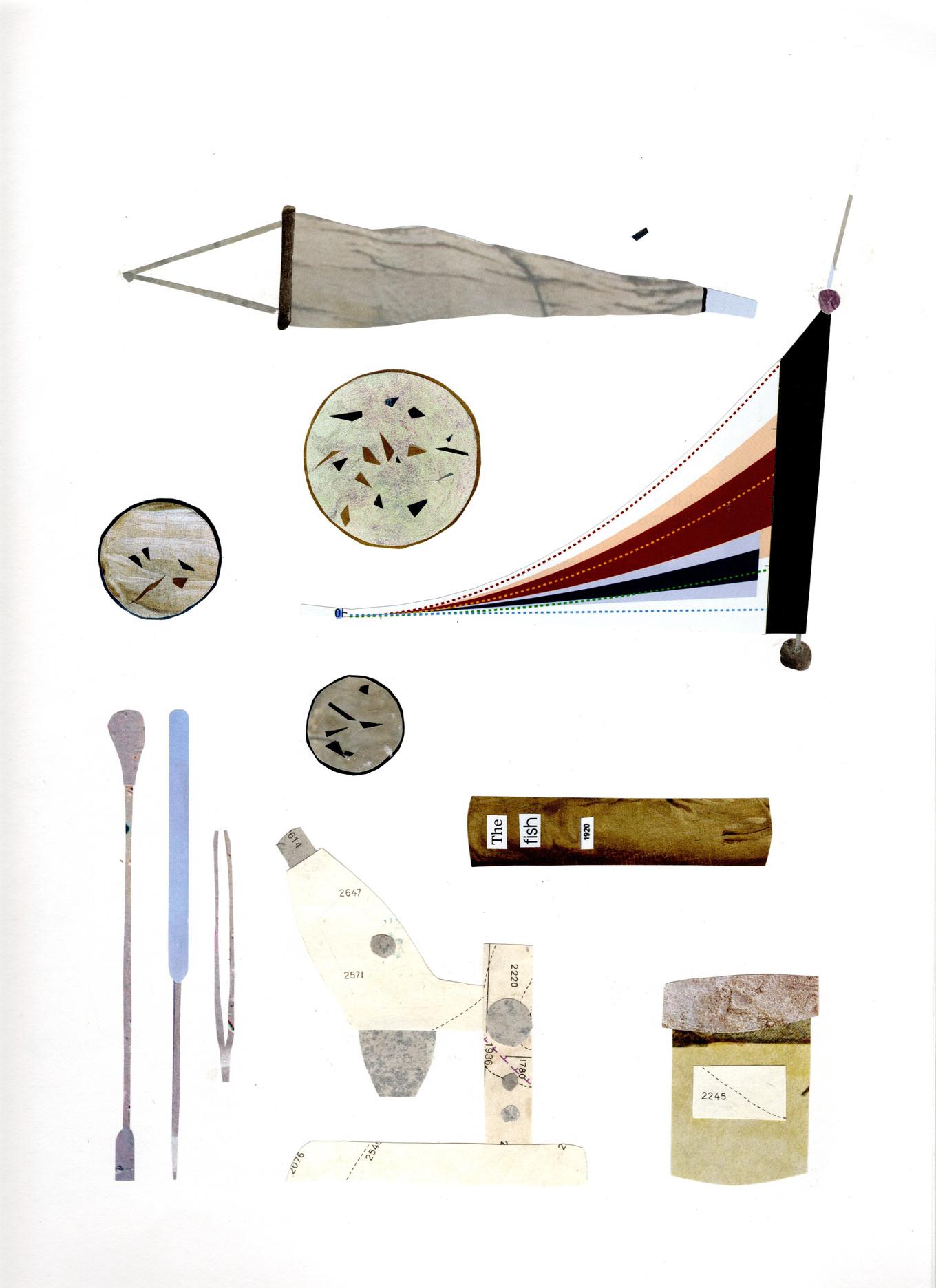

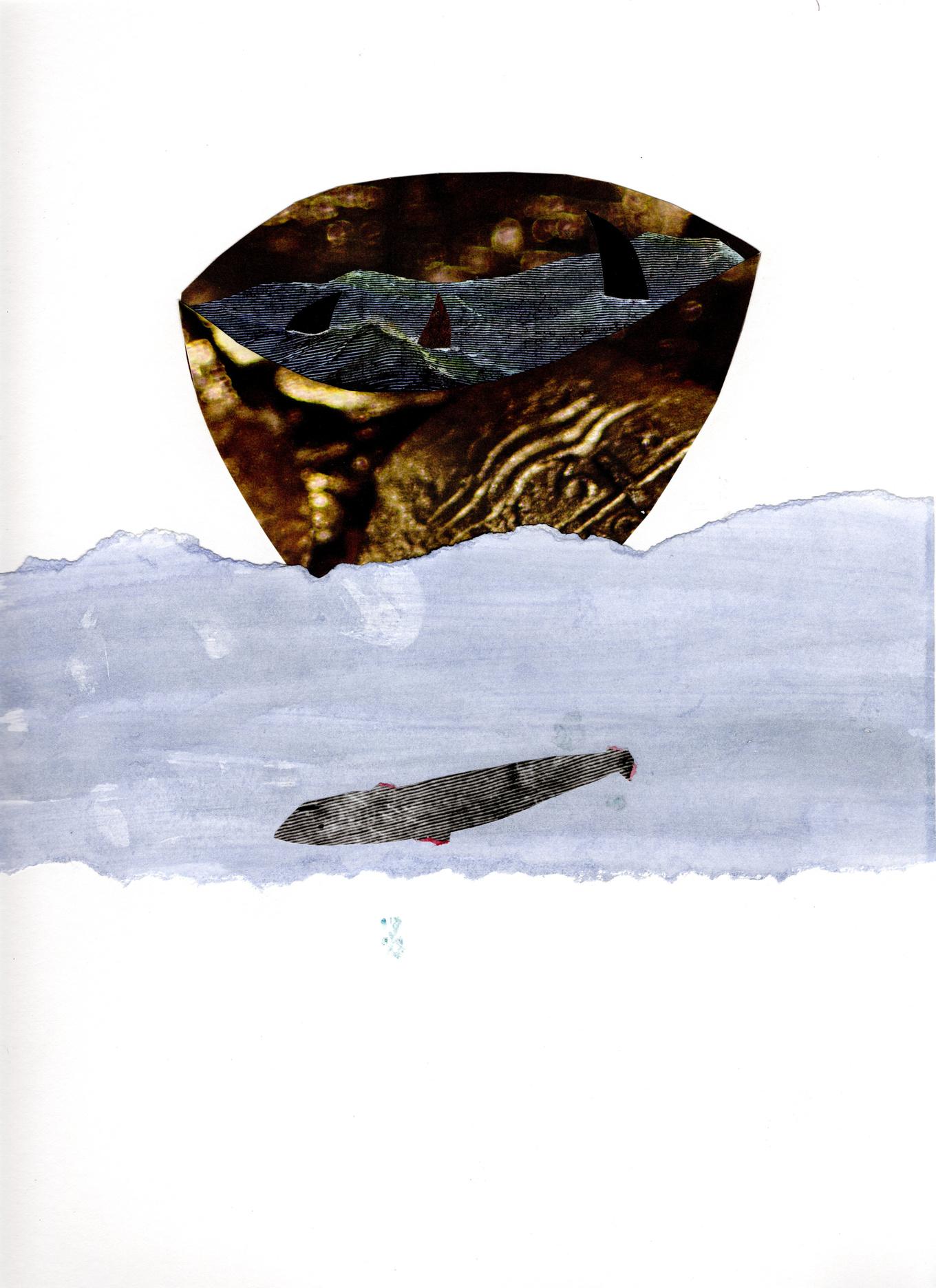

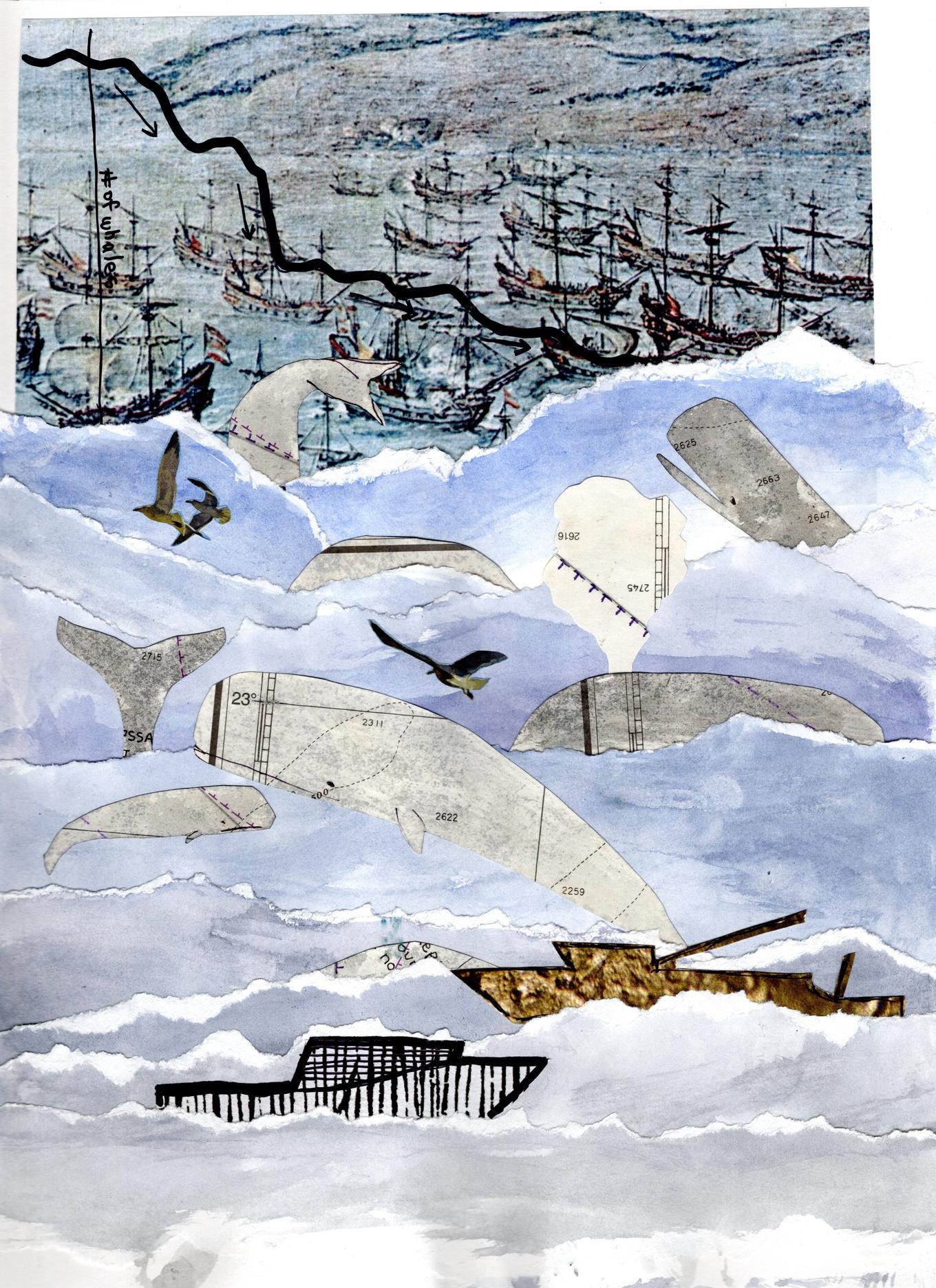

Collage Art and Voyage Map: Hannah Gerrish

Original Canva Template: Zuzanna Witek

Editors: Mallory Hoffbeck and Richard King

Captain: Rick Miller

Chief Scientist: Blaire Umhau

S’310 Mission and Ethics Statement

In Woods Hole we collectively drafted the below, which Autumn Crow consolidated, and then we revised. It’s a document we revisited while at sea, and it was posted on the bulletin board in our ship’s library

We, SEA Class S-310, aim to conduct ourselves ethically throughout our time from Hawai'i to Fiji and potentially through the Phoenix Islands Protected Area and everywhere in between through our work and travels as students, researchers, and tourists. In order to maintain the highest standards of ethical conduct, we will adhere, to the best of our abilities, to the following standards:

As students, we will try to:

Recognize the importance of ethical behavior, and actively seek to acquire the knowledge and skills necessary to embody it.

Continuously challenge our assumptions, evaluate our perspectives, and remain openi d d t di d i d ti

As researchers, we will try to:

Report our findings accurately and conduct unbiased research honestly as we try to identify our potential conscious and unconscious biases.

Recognize the broader benefits of our baseline data, as well as our individual study

ISSUE 2, 2023 cont'd >

S’310 students, SEA staff, and Professor Randi Rotjan (teal sweater) with Ambassador Teburoro Tito (tie)

Attempt to mitigate any ambiguity in our data to prevent future misuse and misinterpretation

Share our data with the local communities of the area we are studying. (For this cruise the full report will go to Kiribati partners after the trip, and then we will first check with all other research collaborators regarding the sharing of our data for this cruise We’ll put clear instructions on how to contact us in our magazine, considering F.A.I.R. use principles, as discussed in Proulx, et al, 2021, in our C&M reader, for anyone who wants access to our findings.)

Recognize the historical and present-day use of science as a tool of oppression by some and actively work to address it.

Evaluate the potential and actual harm of our research, and take steps to minimize any negative impacts

Understand and mitigate the environmental consequences associated with data collection. Learn and incorporate native names for flora and fauna we encounter, whenever possible

As tourists, at sea and on land, we will try to:

Leave every place we visit better than we found it

Show respect for the land and sea, recognizing our place within the natural environment

Acknowledge the central role of the sea in our journey, studies, and the broader purposes it serves beyond our own

Recognize the privilege we have to travel through the Pacific, and acknowledge that our presence is not an inherent right, just as it is not our inherent right to acquire local knowledge in this region or to conduct research.

Have fun and enjoy ourselves as a way to celebrate the gifts of this voyage and this place!

Oceanographic Overview

S

SV Robert C. Seamans

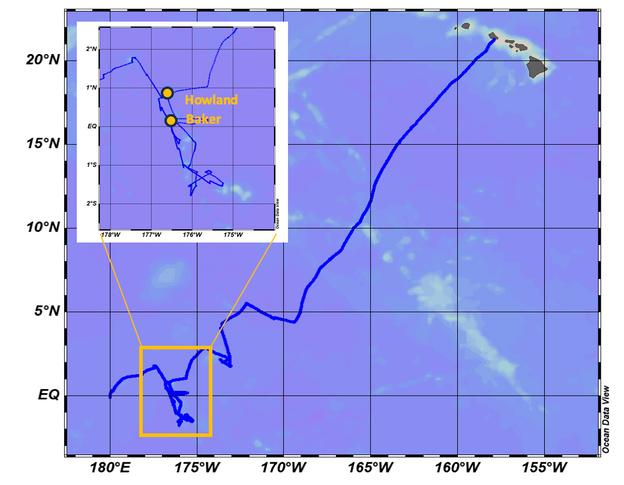

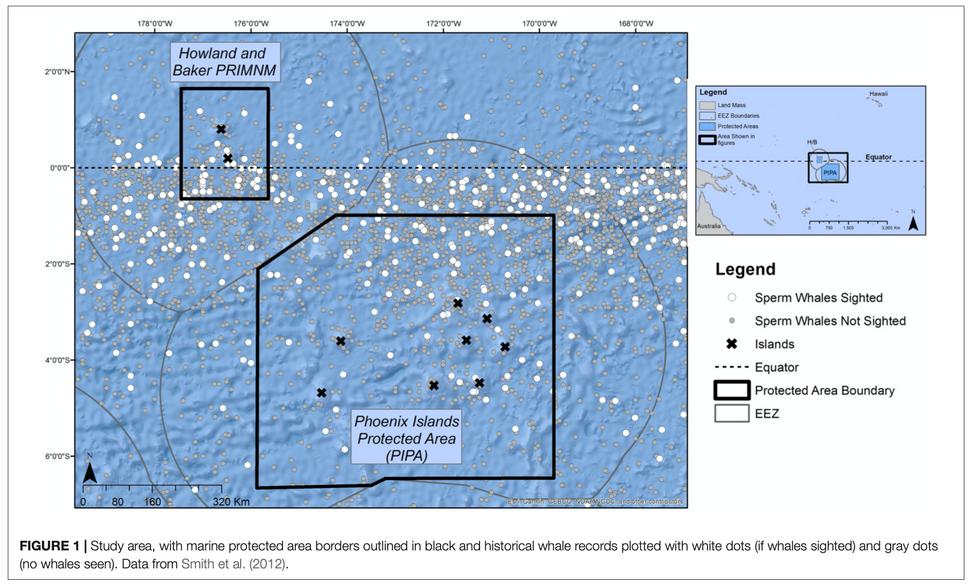

sailed from Honolulu, Hawai’i to Denerau, Fiji from June 23rd through August 8th, 2023 Along the way, data were collected across a range of biogeographic zones, beginning in the subtropical equatorial Pacific south of Hawai’i, moving into the equatorial current system and ending with high resolution sampling on the eastern and western sides of the chain of seamounts straddling the equator that includes Howland and Baker Islands. These islands are part of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument (PRIMNM) and are both designated as wildlife refuges While they are governed by the United States, Howland and Baker Islands are considered part of the Phoenix Islands group, most of which is governed by the Republic of Kiribati Scientific sampling ended once leaving the chain of seamounts, and the ship continued sailing south to the final port of Denerau, Fiji.

by Blaire Umhau

by Blaire Umhau

This six-week cruise contributed to a bank of data on upper ocean plankton populations and supporting physical and chemical parameters. Data were also collected that may provide insight to pelagic ecosystems surrounding seamounts Samples collected within the boundary waters of Howland and Baker Wildlife Refuges provide a unique record of marine ecology in areas with limited anthropogenic

cont'd >

ISSUE 2, 2023

Track of scientific sample collection for cruise S’310 Inset shows the locations of Howland and Baker Islands

Hawai’i

influence, as these islands are uninhabited and strongly protected from anthropogenic activity by the US Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Seafloor bathymetry, current velocity, sea surface salinity, sea surface temperature surface in-vivo chlorophyll fluorescence data were collected continuously along the cruise track.

Vertical water column profiles were collected using a carousel equipped with twelve two-liter Niskin bottles and sensors for dissolved oxygen, photosynthetically available radiation , in-vivo chlorophyll-a, and conductivity, temperature, and depth. Discrete water samples were collected and analyzed for pH, total alkalinity (TA) and chlorophyll-a.

Phytoplankton samples were collected daily using a small drift net Zooplankton and micronekton (tiny fish and squid) samples were collected during daytime and nighttime stations using a neuston net for samples from the surface layer and a tucker trawl for samples from the surface down to a depth of 100 m. During daylight hours, data on seabirds were collected using hourly observations.

Student projects using this set of data focused on bathymetry comparisons between observed and published data, the distribution of pH, alkalinity and dissolved CO2 concentrations, phytoplankton

by Blaire Umhau

abundance and community composition, zooplankton abundance and community composition, and seabird abundance, community composition and behavior.

Further Reading

and the Data from this S’310 Cruise

Blaire P Umhau, “Final Report for S E A Cruise S310” (2023): Sea Education Association, P O Box 6, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA.

To obtain this report for free or see the unpublished data, contact Blaire Umhau (bpumhau@gmail.com) or the SEA Data

Archivist:

Data Archivist

Sea Education Association

P O Box 6

Woods Hole, MA 02543 USA

Phone: 508-540-3954

Fax: 508-457-4673

E-mail: data archive@sea.edu

Web: www.sea.edu

A Passage through the Torrid Zone

hat’s the image you have after reading the title? Centuries ago, when Europeans were expanding their exploration of the world on sailing ships, they experienced the increasing temperatures as they sailed south, determining eventually that the heat would prevent passage. This was called the Torrid Zone. Would your image be different if the title was “Sailing through the

WTropics”? The Torrid Zone and the Tropics share a common definition today, the area between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn. This is the area where solar radiation meets perpendicular to the earth’s surface creating the most intense heating of earth. Compare this to the polar regions where the sun’s solar radiation encounters the earth’s surface at a relatively small angle, spreading its heating effect over a large area. Think of a flashlight aimed directly at a wall (a focused circle of light)

by Rick Miller

by Rick Miller

cont'd >

ISSUE 2, 2023

compared to holding the flashlight at a small angle to the wall (its light spread in a large cone shaped pattern). Due to the tilt of the earth’s axis relative to the plane of its orbit around the sun, that perpendicular encounter to the earth’s surface shifts between 23 1/2° north to 23 1/2° south each year. This is what defines the tropics (and the Torrid Zone)

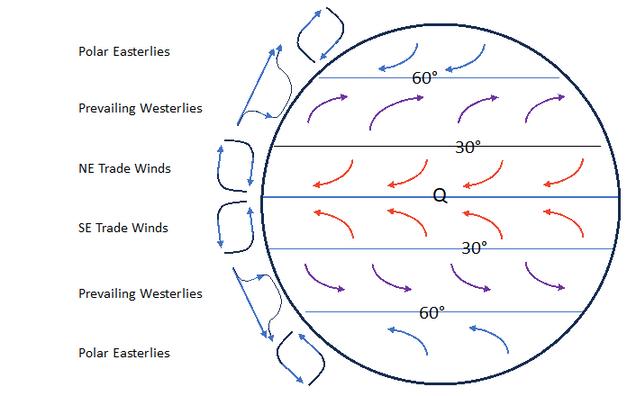

The Torrid Zone is part of a trio of zones, bordering the Temperate Zone, followed by the Frigid Zone. Respectively, the Tropics too are part of a trio, associated with the Mid-latitudes and the Polar region. The varied angle of encounter of solar radiation heats the earth and its atmosphere differently at different latitudes. The atmosphere is always seeking a balance, a common temperature. This is what creates our winds and our weather! A global model provides a visual representation of what happens as the atmosphere tries to balance the heat of the tropic with the cold of the polar regions.

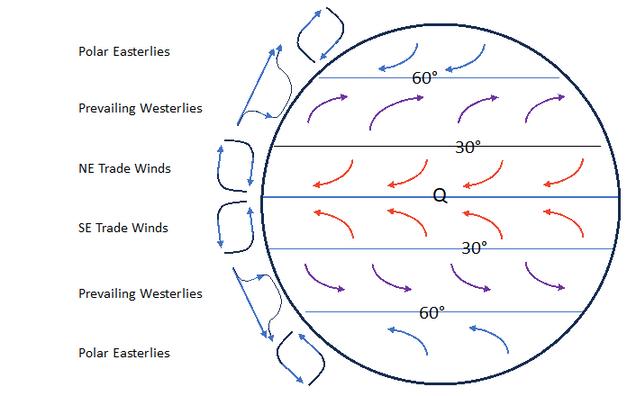

The Global Circulation Model

In the model above the curved arrows inside the circle (the globe) represent surface winds. The arrows outside the circle show the vertical motion of air movement as well as the upper air wind direction. This is a continuous cyclical pattern, so there is no specific starting point,

by Rick Miller

but the equator (Q) will be the initial reference. Air at the equator is hot and humid, it is also forced to rise due to converging winds (see the red arrows) as well as being hotter than surrounding air. Rising air creates low pressure at the surface The equatorial region is a belt of low

pressure. As any air rises, it expands (less pressure) and cools The cooler air cannot hold as much water vapor, so condensation occurs forming clouds. The equatorial area receives ample rain throughout the year. The equatorial air that has risen moves north or south toward the poles to cool off The Coriolis Effect turns those upper air winds (right in the Northern Hemisphere, left in the Southern) resulting in a ‘pile up’ of upper air around 30° N or S. As the air piles up, it gets heavy and falls (subsides) to the surface. The upper air is very dry having lost most of its water vapor to cloud development at the equator. As the air falls, it is compressed (greater pressure) and warms more. The falling air creates a

cont'd >

The atmosphere is always seeking a balance, a common temperature. This is what creates our winds and our weather.

band of high pressure in this belt known as the Sub-tropical High (or Horse Latitudes). The arid desserts on earth all are found in this region The air falling and hitting the surface must now spread out, some moving north, some south. The air moving toward the equator is turned by the Coriolis Effect resulting in the northeast or southeast trade winds (red arrows). The trade winds blow very consistently throughout the year. There is little to disrupt this pattern. The meeting of the northeast and southeast trade windscreates the convergence referenced above. This is called the inter-tropical convergence zone (ITCZ).

For reference, there is another convergence zone near 60° N or S where the prevailing westerlies meet

by Rick Miller

the polar easterlies. This convergence is known as the polar front and is very different than the ITCZ. At the polar front the winds are converging in opposite directions (westerly/easterly). The westerlies are typically warm and humid while the easterlies are cold and dry! This too is an area of ample rainfall, but also the area where low pressure cyclones are formed. These lowpressure areas, familiar in the midlatitudes, disrupt the prevailing winds regularly and create the ever changing weather in this region.

The cruise track for the SSV Robert C Seamans and the crew of S’310 “Protecting the Phoenix Islands” departed from Honolulu, HI, sailed to the US Phoenix Islands (Howland and Baker Islands) where cont'd >

focused data collection took place before continuing on to Port Denarau, Fiji. Honolulu is located near 20°N latitude while Port Denarau is near 18°S latitude. Our passage was in the Torrid Zone! Overall, this made for good sailing, with consistent easterly winds driving our ship south The trade winds, both northeast and southeast, provided the winds that allowed us to sail the 4,600 nautical miles through the tropics.

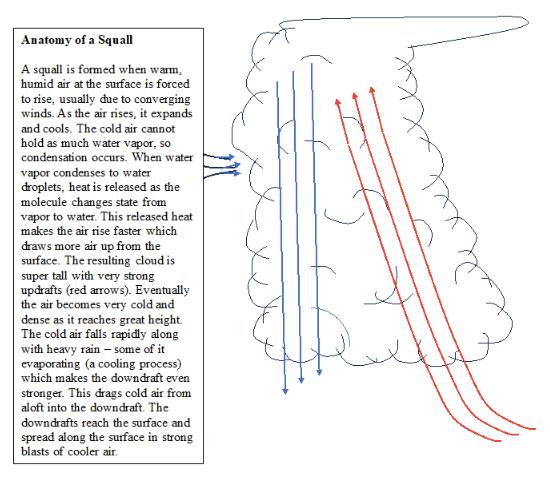

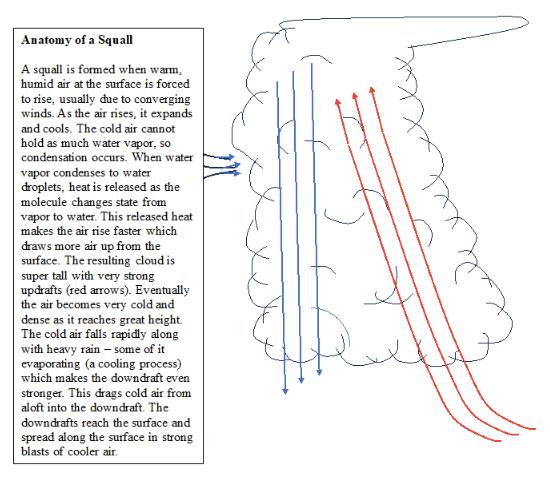

Our research took place in the US Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), a two-hundred-mile radius of territorial waters surrounding Howland and Baker Islands. A special permit allowed us to enter the Marine Monument, a defined protected area around Howland and Baker Islands. Our research plan had the Robert C Seamans zig-zagging north and south, deploying science equipment twice each day – morning and night. Data collection was intentionally positioned on the “upstream and downstream” sides of a chain of sea mounts (underwater mountain range!) which also included Howland and Baker Islands. It was here doing research where the ship first crossed the equator! Howland and Baker Islands are located near 2°N to 4°N latitude Sailing here in July for over two weeks the ship and crew were located at the ITCZ. The Intertropical Convergence Zone produces

by Rick Miller

by Rick Miller

frequent ‘squalls,’ small to large cumulonimbus clouds that can bring strong wind, heavy rain, and occasionally lightning. This region was also HOT! and was the inspiration for the article title. The crew did a great job maintaining a vigilant eye for weather and were ready to reduce our sail area whenever a larger squall threatened high winds. The rain was often a relief from the hot sun and there were a couple of fortunate days with little wind that allowed the ship to “heave to’ for a swim call in midPacific!

That’s a quick overview of our passage weather! The reliable trade winds and the ITCZ. As the cruise approached Fiji the ship encountered its first front, where warm air met cooler air from the south. The equatorial temperatures dropped noticably as we comfortably sailed to Savusavu where the ship and crew cleared customs and immigration and enjoyed a short visit before reaching the final port near Nadi, Fiji

"Carbon Dioxide Fugacity and Ocean Acidification: A Silent but Deadly Threat"

y absolute favorite aspect of this journey, traveling across the Pacific Ocean from Honolulu, Hawai’i to Nadi, Fiji on the Robert C. Seamans, was my time spent in the laboratory. Students and deckhands were allotted time during the watch rotations to gather, process, and analyze data for several unique research projects My project was shared with my partner Hallie Rockcress. We collected water samples at multiple water depths twice per day and processed for pH, total alkalinity (the water sample’s ability to resist pH changes), and chlorophyll-a With the pH and total alkalinity values, we could calculate the carbon dioxide partial pressure (the concentration of carbon dioxide in the water). We also compared the fugacity of CO2 to the deep chlorophyll maximum. That’s the point at which there is an abundance of chlorophyll in the water column, which normally indicates activity

by Olivia Patrinicola

Mfrom phytoplankton. This project is incredibly important to my partner and I, and we hope to add to the general knowledge of the chemistry of the equatorial Pacific Ocean.

As we stumbled from one side of the lab to the other as the boat rocked back and forth, we continued to learn more about the pH of the waters that we sailed through. I had become more and more invested into the issue with every sample processed. While pH levels may seem better here due to our close proximity to the equator, it took an

cont'd

cont'd

>

ISSUE 2, 2023

Hallie and Olivia hard at work gathering water samples from the carousel (Hannah Gerrish)

immense amount of effort, time, and people to gather all of the data used for our research project. It put climate change scientific research into perspective, especially with how much it will truly take to create change, and how the acidification of the seas requires the help of everyone to turn things around

For the past thirty years, there has been increased activism and policy making to work against climate change. But we must ask ourselves if we are truly doing enough. The root of the issue within our seas is decreasing pH levels caused by temperature fluctuations

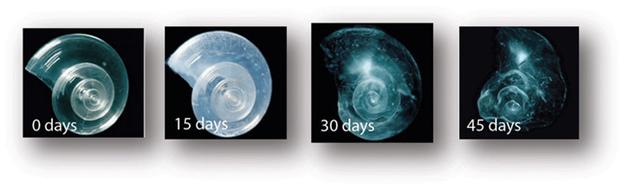

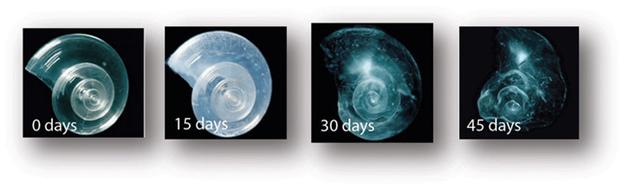

atmosphere. Currently, average pH levels around the world are between 8.0 to 8.3, which, depending where on the globe you are, is considered healthy enough to support marine life. If we continue to create carbon emissions at our current rate, and even faster, according to the 2022 IPCC report, the pH will likely slip below 8.0 and the degradation of life under the sea will occur exponentially. The US Ocean Climate Action Plan predicts that at this rate the planet will reach two degrees Celsius of warming by 2100. A large effect of ocean acidification is the dissolution of calcium carbonate

globally. This is something that affects the core chemistry of the seas and cannot just be relieved with light policy. According to a 2019 study by Harrould-Kolieb and Hoegh-Guldberg, the seas are now twenty-six percent more acidic than they were since before the Industrial Revolution. The oceans also act as a carbon dioxide sink, which means that it absorbs CO2 from the

by Olivia Patrinicola

by Olivia Patrinicola

shells. When the calcium carbonate bonds break from the added carbon dioxide, organisms such as bivalves and coral experience structural weakness, which normally leads to death of the organism. Due to anthropogenic ocean acidification, coral reefs have experienced extensive damage and death, which has resulted in mass habitat loss for organisms who rely on reef

cont'd >

Calcium carbonate shell dissolution as an effect of ocean acidification (Image adapted from David Littschwager/ National Geographic Stock)

ecosystems

The United States released their Climate Ocean Action Plan this past March 2023, which includes several sections that review ocean acidification. I believe this is a success and will lead towards more success, as it is one of the first occasions that ocean acidification is included in the conversation when discussing climate change in general US governmental reports. The plan is useful because there is a scientific version, and a much simpler version online. The simpler version is aimed

need to get on the problem is something the plan focuses on, which is a newer development in the United States. Some of the other aspects of the document include the promise of a physical plan in the next coming months, increased data collection and scientific efforts, forming resilience for coastal and stakeholder communities, mitigation efforts, and including ocean acidification in the conversation for geoengineering projects The plan goes as far as mentioning that ocean acidification is a high priority in the list of climate change related issues and that an additional Ocean Acidification Plan will be released in this year.

to educate those who do not know anything about ocean acidification, which is currently very common, even in the climate action world. The official version of the Action Plan covers detailed aspects, while the other contains more accessible information The authors state, “Many of the species that are at risk have high commercial, cultural, and biodiversity value, lending urgency to the need to reduce ocean acidification.” Emphasizing the dire

by Olivia Patrinicola

A global effort similar to the US action plan is the International Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC. This is a gathering of scientists of a multitude of educational backgrounds around the world that form a regular report on the climate situation. It covers every corner of climate change that can be studied and explored. The most recent report was released in 2022 and is now the 6th report the IPCC has released. The report is hundreds of pages long and mentions the effects of climate change on a scientific level. The panel is not allowed to form policy, only create suggestions. The IPCC reports have not always mentioned ocean acidification and how directly it relates to climate change, but the

cont'd >

The first step to helping the seas maintain a viable pH level is by remaining educated and up to date on what is going on around the globe.

more recent reports, especially the 2022 report, extensively describe ocean acidification and its damaging effects to the planet. Unfortunately, with the IPCC’s inability to physically do anything besides release their report, some argue that it isn’t that useful in tackling climate change.

In addition to the US Climate Ocean Action Plan and the IPCC reports, the United Nations has formed several efforts over the past thirty years in the form of agreements, to boost climate change action The most recent, the Paris Agreement (2015), only slightly covers ocean acidification. The issue with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is that these agreements do not hold any country accountable. The promises representatives make can only be monitored for improvement and implementation, but those who choose to be in the agreement are not bound by any law. The US, for example, pulled out of the Paris Agreement during the Trump Administration and later re-entered the Paris Agreement during the Biden Administration. Yet these protocols and agreements made under the UN are still useful to increase awareness and stimulate action without force.

As we saw a bit of Fiji during the last few days of our tremendous

journey, I reflected on what the future could potentially hold for these ecosystems. The truth is that these diverse fish cities will die out from coral bleaching as the ocean continues to acidify. It is an issue that needs to be tackled immediately and should be of the highest priority. Because of the late addition of ocean acidification in the conversation, it is an aspect not thought about before and needs quick initiation. For example, the anthology compiled by Bill McKibben called The Global Warming Reader- A Century of Writing About Climate Change, gathers articles from 1896 to 1995 that cover global warming over the years. In the earlier scientific documents, ocean acidification is never mentioned, proving that ocean acidification is a newer point of conversation Many plans and policies have been made that focus on carbon emissions around the globe, several are covered in the agreements, plans, and reports addressed above

I encourage readers to further explore the readings below on ocean acidification, policy, and climate change. The first step to helping the seas maintain a viable pH level is by remaining educated and up to date on what is going on around the globe. Reading the IPCC reports, keeping up with Climate Action Plan developments released by the cont'd >

by Olivia Patrinicola

United States government, and supporting smaller climate action organizations, are all proactive methods to staying informed.

by Olivia Patrinicola

Further Reading

Harrould-Kolieb and Hoegh-Guldberg, “A Governing Framework for International Ocean Acidification Policy” Marine Policy 102 (April, 2019): pp. 10-20.

US Ocean Policy Committee, Ocean Climate Action Plan (United States: The White House, March 2023): https://www.whitehouse.gov/wpcontent/uploads/2023/03/Ocean-ClimateAction-Plan Final pdf

IPCC, International Panel on Climate Change (2022): https://www ipcc ch/report/ar6/syr/

United Nations, Paris Agreement, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2015): https://unfccc int/process-andmeetings/the-paris-agreement

Bill McKibben, ed. The Global Warming Reader- A Century of Writing about Climate Change (London: Penguin Books, 2012)

Teaching Climate Change in the Midst of Catastrophe

hen surrounded by water, the whole ocean changes with the sight of land. As Howland Island appears on the horizon as a tiny white strip, the ocean suddenly turns from an endless, infinite, blue space to a finite space with perceptible edges. In the infinity that is the ocean, when there is only blue on all sides, it’s difficult to picture the ocean rising It’s hard to imagine sea level rising as the ocean itself constantly shifts, rolls, and waves. Despite the obliviousness to change as I move constantly on the Robert C. Seamans, the ocean is rising. Thousands of islands are in danger, particularly within the Pacific Ocean as sea level rise could near one meter, coinciding with a potential global increase of 3 C°, by the end of the century.

As Howland peeks above the horizon, the gravity of sea level rise becomes evident Howland sits six meters above sea level. A few

meters of sea level rise will drastically alter the geography of Howland. As an uninhabited island, one could argue (though I will not) that there is a lesser reason for concern. But what about Fiji, Nauru, the Cook Islands, and more in the Pacific Ocean and others across the world that host whole populations? It’s projected 150 million people could live below sea level by 2050 Sea level for islands in the Pacific as well as the many other places that will be impacted, has the potential to be completely catastrophic to their way of life.

In the face of this catastrophe and dire consequences, education will be central to mitigate climate change and associated sea level rise. So how can K-12 teachers, specifically in the United States, effectively educate the youth about sea level rise and climate change as a whole, regardless of their students’ proximity to the ocean? How can students meaningfully learn about sea level rise in oceans thousands of miles away? As we consider broader implications of climate change, how

cont'd >

W

by Autumn Crow ISSUE 2, 2023

can teachers inspire stewards of the earth and promote proenvironmental behavior in students?

How do we teach about climate change and sea level rise in the midst of catastrophe?

Talking and teaching about climate change is a precarious activity. Though various research shows benefits to both optimistic and pessimistic climate change narratives, climate anxiety and hopelessness are very real and everincreasing feelings that can be pervasive in the face of learning about imminent climate change. For teachers of any age level, from K-12 to university students, climate change can be a heavy and sensitive subject. Though we like to shield our

by Autumn Crow

younger students from harm and harmful ideas, it is imperative that our youngest students learn about climate change and start doing so from an early age. Though it is easy to get carried away with doom and gloom, it is important to expose our students to both climate change optimism and pessimism. Since both narratives have a role in creating pro-environmental behavior, how can we provide healthy doses of both to our students, while tailoring our education to the ages, cultures, locations, and more of those we are teaching? How can we create spaces for our youngest children to learn about climate change safely but effectively at an age-appropriate level? It’s impossible to provide

cont'd >

W

The great endless blue of the Pacific Ocean July 28th, 2023 at 5°56 0’ S x 179°17 1’

satisfactory answers to all the above questions, but below we’ll attempt to answer what we can in how to prepare our students in the fight against climate change and sea level rise.

Ages 0-6

Even before traditionally schoolaged, children should be learning about climate change. Though not in traditional schools yet, many children spend time in daycares and attend in preschool programs prior to enrolling in public kindergartens. Early childhood educators have a pivotal role in introducing youth to the environment and fostering unwavering love for the Earth and the environment as a whole. This comes from experience and exposure. For our youngest learners who have accessibility to nature, kids should be in nature as much as possible. It is important to note there are broader socioeconomic and cultural implications as to who has access (both temporally and spatially) to green spaces and those who do not, but the US should continue to strive to enable all kids and families free and easy access to natural spaces. For rural and suburban communities, students may have ready access to natural spaces, large or small. Bigger field trips and outings can introduce students to national parks, preserves, green spaces, coastal areas, and more. But natural

by Autumn Crow

exposure should not be reserved for special occasions, larger trips, and those in urban/suburban environments Educators of our youngest learners should endeavor to incorporate the natural world as much as possible, with visits to parks, playgrounds, and outdoor school yards. Exposure to nature needn’t be exhaustive or exhausting for teachers and care providers of young children. Creating space for students to be outside and notice things in the world is a significant start in climate change education for our youngest learners by exposing them to the outdoors that surround them.

Ages 6-12

Once students are traditionally school-aged, schools become a larger socializing force for youth. Students first encounter the formal opportunity to learn about climate change At this age, it is important that students begin to learn the science of climate change to establish a correct and comprehensive understanding. Of course, it

cont'd >

Creating space for students to be outside and notice things in the world is a significant start in climate change education.

is pertinent to design curriculum that is conceptually appropriate for students through these ages. In addition to introducing the scientific basis of climate change, this age of students is also suited to emphasize climate change solutions. Emphasizing solutions, whether potential or current, can balance the negative messages often infused in discussion of climate change catastrophe. Despite popular messaging, there are solutions to climate change and positive steps being introduced throughout the world Similarly, through personal action, students can feel empowered to devise their own solutions and contribute to positive actions on climate change. Whether as a class or as individuals, students can devise their own projects to make a positive impact on the environment even if not directly related to climate change, such as picking up litter, using less water, and talking with their family about their impact.

Ages 12-14

As students grow older, climate change education can shift to discussion involving students’ thoughts and opinions as well as opportunity for further selfexpression Discussion can allow students to ask questions, demonstrate interest, and explore areas of their own interest. Furthermore, with advancing studies and schools that begin to departmentalize, it’s

by Autumn Crow

important to know that climate change education cannot and should not be constrained to physical science courses like earth science and environmental science. Self-expression is a way to incorporate climate change material into other disciplines, such as through art. Whether through visual, performance, or written art, students can be provided the opportunity to express their own opinions, thoughts, and ideas in ways that help them to process big emotions and ideas. Beyond expression, non-physical science disciplines can incorporate learning about climate change through activities such as reading literature, watching movies, and completing self-designed research projects.

Ages 15-18

In the final grade levels of K-12 education, students reach a space where they are capable of complex, multi-faceted thought and problem solving as well as continual development and refining of their own opinions. This age group provides opportunities for educators and other adults to learn from students in unique and productive ways. However, with advancing understanding and a greater world view that older students possess, it becomes more pertinent to teach and demonstrate coping skills to students as they struggle with potentially traumatic and scary cont'd >

ideas. Modeling coping and self-care skills is central to helping students develop those skills at the high school level As prominent adults in the lives of students, demonstrating coping skills as an adult grappling with climate change is a key step for enabling students to do the same, especially at the notoriously emotionally turbulent age of high school

observations, drawing a part of nature, or any other task in the outside world could provide structured opportunity for students to get acquainted with nature.

Finally, on variable levels of difficulty and involvement for the ages of our students, inquiry-based, problem-based learning can be central to sparking interest, motivating learning, and creating a productive and educational classroom. Though we can’t ask our students to solve climate change in our classrooms, we can present them with smaller scale problems to address, and ask them to explore and develop their own interests, all the while empowering them as learners and climate activists.

As curriculum that transcends all age levels, we should be encouraging students to explore the outdoors and coexist with nature. We can be creating space either within the school day or permitting (to the best of our abilities) free time away from homework, where students can pursue outdoor endeavors like sports or otherwise to spend time in nature. Furthermore, occasional “outdoor” assignments such as spending time outside, making

by Autumn Crow

So, where is the sea in all of this? Engaging with nature can bring place-based education front and center. When students are learning about the world directly around them, they can connect in a meaningful way and grasp concepts on a level of significance to them. Sea level rise is a symptom of climate change and one that can help us grapple with the stark reality of imminent catastrophe. However, for those who are hundreds of miles away from the ocean and areas widely affected, place-based education cannot illuminate climate change

As a land-locked American from Colorado, sea level rise personally is

cont'd >

In this afternoon class aboard the Seamans, Chief scientist Blaire Umhau (red T-shirt) looks on as student Julius presents on measuring current, while Noah looks at a recently collected biological sample

not a significant concern. I find myself at sea from a passion for sailing and nature, and though I will not face immediate consequences of sea level rise due to climate change, I will certainly feel other symptoms of climate change. Even on the ocean, as mentioned, it, too, is difficult to picture sea level rise with the ocean constantly shifting around me However, on the Pacific, no moment is more real to sea level rise than spending 2,000 miles sailing with only the vast blue and then seeing the sliver of an island such as Howland on the horizon When you realize there is land in this watery world, the whole ocean shifts With that shift, however, it’s blatantly obvious how seemingly vulnerable a tiny strip of land is in the vast expanse of ocean. Not everyone can experience this In fact, few will sail the remote areas of the Pacific and feel the change when land appears on the horizon.

In June, when this SEA class met with the former president of Kiribati and current UN Ambassador Tito, it humanized the consequences of climate change. Getting to shake the hand of a man whose home is thousands of miles away and increasingly threatened by the sea was illuminating. In 2012, current President Anote Tong of Kiribati purchased 6,000 acres of land in Fiji for potential migration of his people

by Autumn Crow

by Autumn Crow

in the future. A Kiribati emigrant, Ioane Teitiota was denied asylum in New Zealand under the claim of unlivable conditions in Kiribati due to climate change These are very real examples of the imminent effects of sea level rise due to climate change on a unique group of people. Though we all cannot fathom sea level rise on the level it will impact these island nations such as Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, Tuvalu and more, possibly within the decade, climate change is impacting all of us every day in all our

cont'd >

While at sea, how do we conceptualize sea level rise and think about its impact on people ashore?

surroundings. States are alighting in flame; species are disappearing; storms and drastic temperature changes afflict our nation. But, at the same time, communities are coming together to defend and create wild spaces, students are learning and exploring climate change inside and outside of the classroom, and research continues to create the best future for our world. If, in exploring the world around us, we can find these other symptoms of climate change, near or far from the ocean, and illuminate them for our students, we can provide them the image and knowledge they need to recognize and fight against climate change. Climate change will be overcome with a sense of place, a sense of love, and a sense of belonging. It begins with our youth. It begins in the hands of our teachers.

by Autumn Crow

Further Reading

Education

Anya Kamenetz, “8 Ways To Teach Climate Change In Almost Any Classroom” (NPR, 2019): https://www npr org/2019

Anya Kamenetz, “Most Teachers Don’t Teach Climate Change; 4 In 5 Parents Wish They Did” (NPR, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019.

Lora Shin, “Your Guide to Talking With Kids of All Ages About Climate Change” (NRDC, 2019): https://www.nrdc.org/stories/your-guidetalking-kids-all-ages-about-climate-change

Sea Level Rise

Christina Gerhardt, Sea Change: An Atlas of Islands in a Rising Ocean (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2023)

Optimism and Pessimism

Rob Law, “I Have Felt Hopelessness over Climate Change Here Is How We Move Past the Immense Grief,” The Guardian (2019): https://www.theguardian.com...

Catherine Clifford, “The Case for 'Hope Punk' When Talking about Climate Change: 'To Be Hopeless Is To Be Uninformed’” (CNBC, 2021): https://www.cnbc.com...

David Skorton, “The Argument for Environmental Optimism: Opinion by Smithsonian Secretary David J. Skorton” (Smithsonian Insider, 2017): https://insider si edu

Zachary King, “Unconventional Optimism: Lessons from Climate Change Scholars and Activists” (Resilience org, 2020): https://www resilience org/stories

Who Holds the Steer?

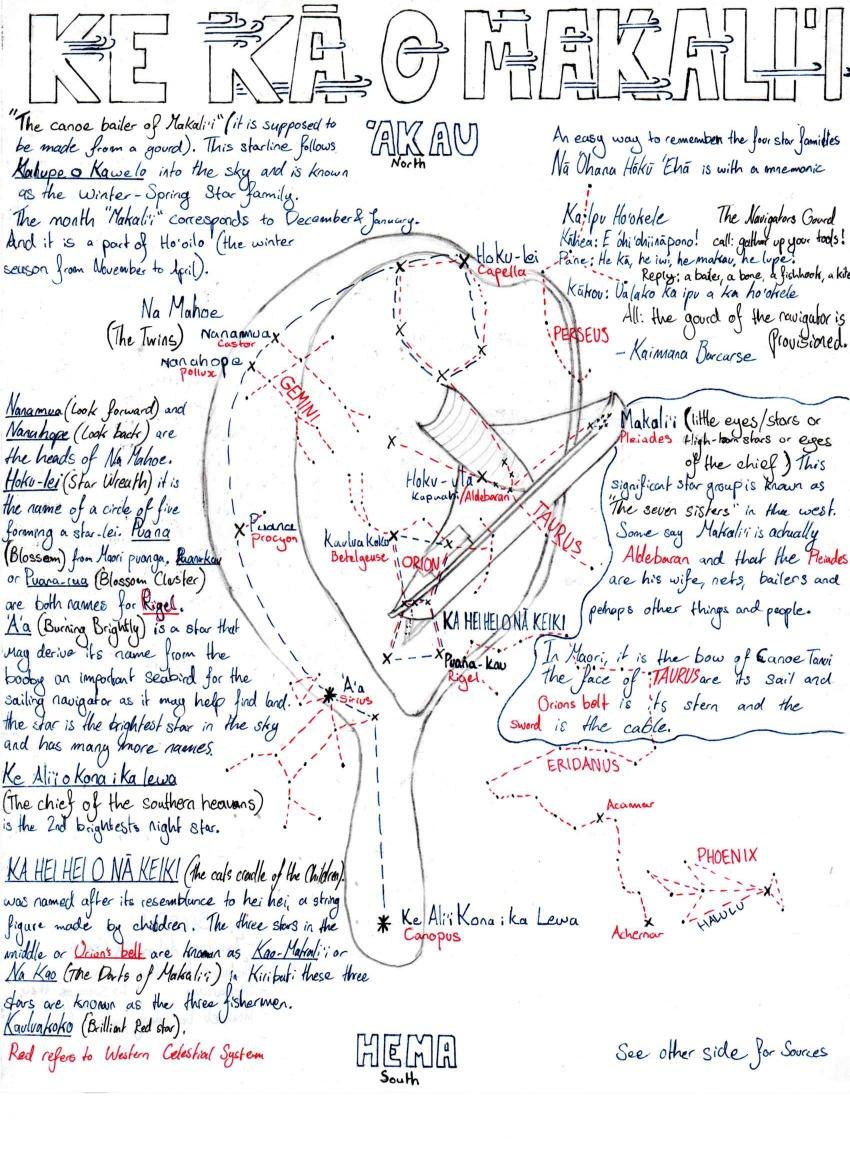

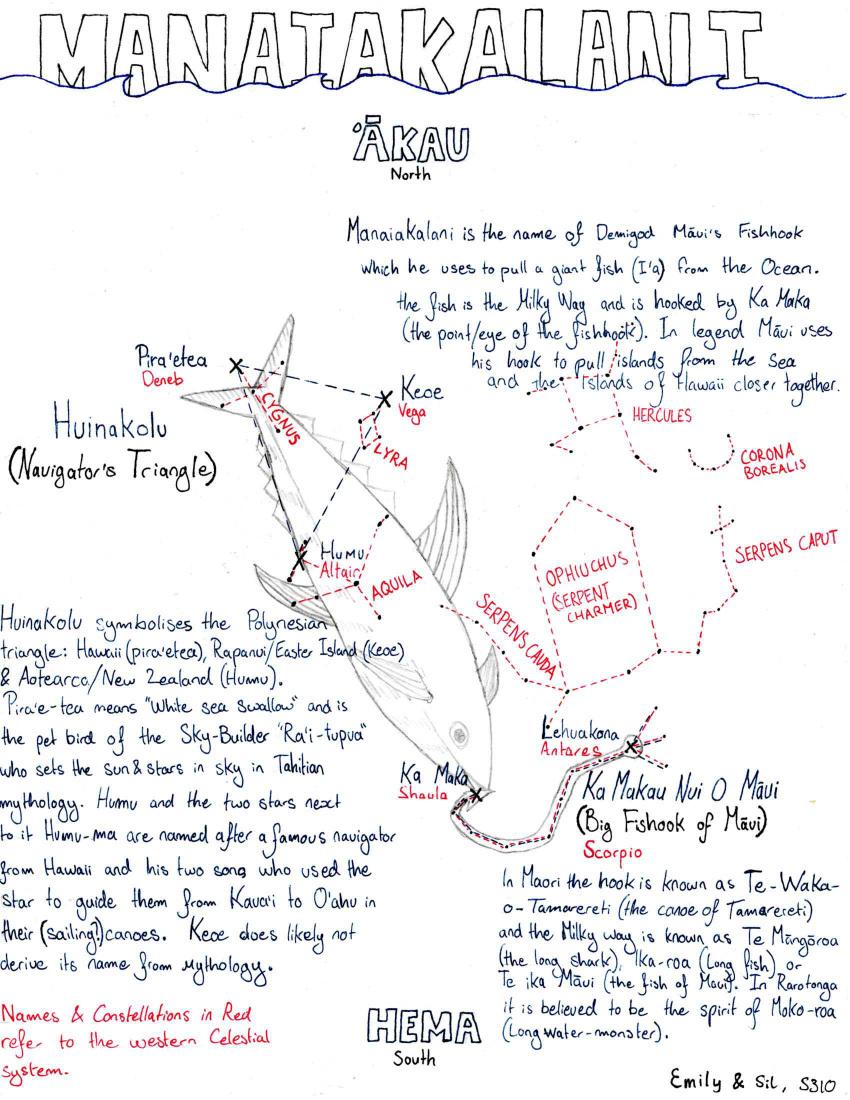

Iam Sil, a young human making passage with all my fellow coassociates aboard the Robert C Seamans. I sailed as a student on C’302 where I often found myself peering into the bright night sky on lookout and frequently steering more than 20° off course trying to identify the constellations, their place relative to one and other and to me.

I studied the Western celestial system (which has many stories and myths from Ancient Greece that were preserved by Arab scholars) intensely on my student trip. I was deeply invested in the stories of Orion and Scorpio, Andromeda and her savior Perseus and many more. Yet the Pacific Ocean is a long way away in spacetime from Ancient Greece and the Arab scholars; and it was also a long way for those “first” explorers like Cook, Tasman, Magellan and many other men looking for a legacy, power, and domination

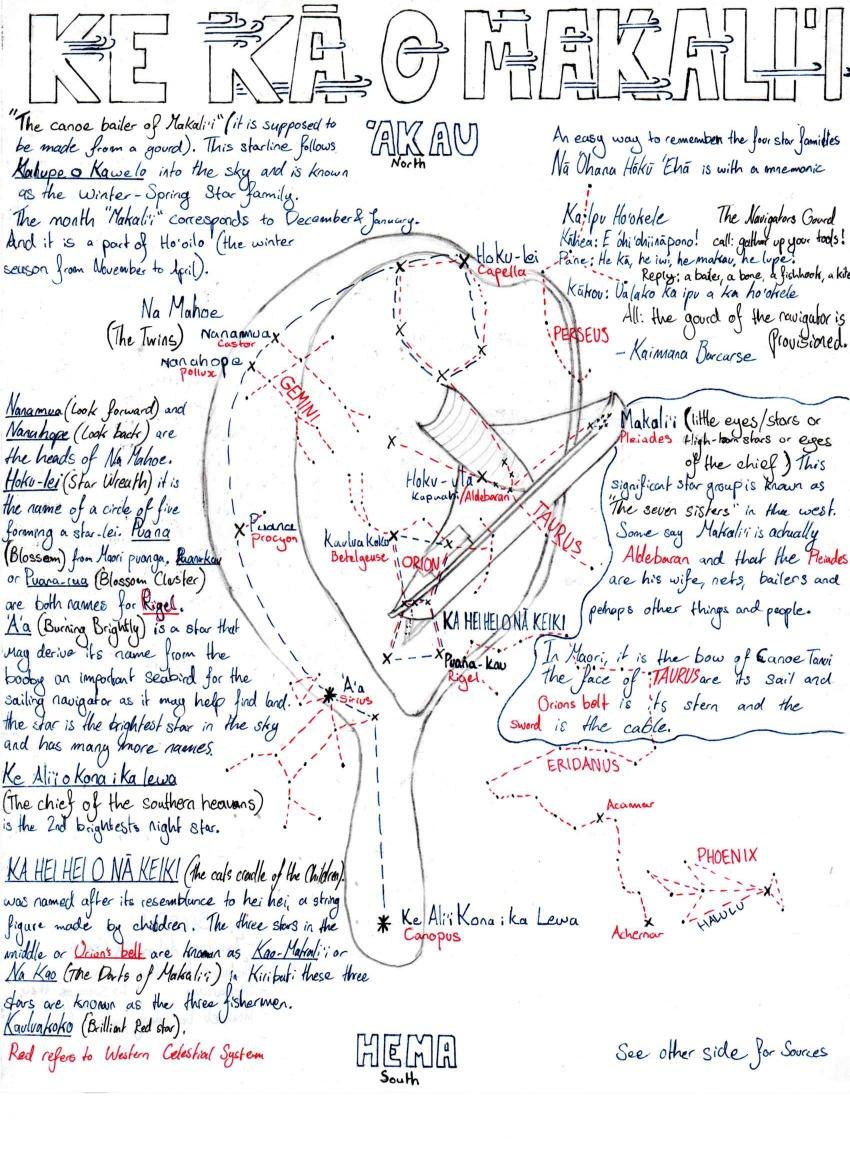

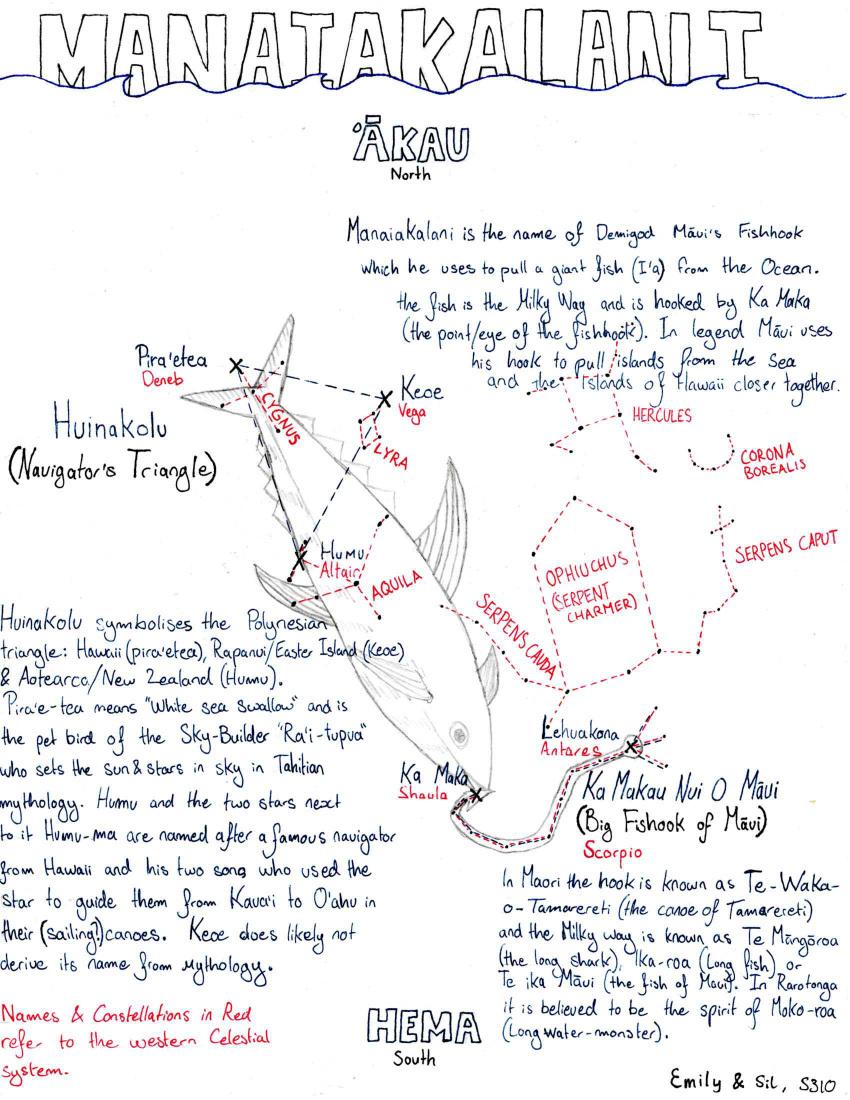

The waters we sail on are sacred, guided by the wind, the current, the

by Sil Kiewiet de Jonge

clouds, the birds, and the stars. Pacific Islanders navigated this ocean long before the conquest of the Europeans. The names of Na’Ohana Hoku ‘Eha, the four star families/starlines from Hawai’i are the Ke Ka o Makali’i (“The Canoe Bailer of Makali’i”), Iwikuamo’o (“The Backbone”), Manaiakalani (“The Chief’s Fishline”), and Ka Lupe o Kawelo (“The Kite of Kawelo/the Chief”)

When the sun set on our first day after leaving Hawai’i the entirety of the Iwikuamo’o connected Hokupa’a (Polaris/North Star) through Na Hiku (Ursa Major/Big Dipper) to Hokule’a (Arcturus in Boötes). Hokule’a is Hawai’i’s zenith star, which means it rises directly above Hawai’i. Although light years away, the warm red glow can be felt on Earth and at sea, thus it is known as “the star of gladness.” If we follow Na Hiku through Hokule’a in an arc we get to Hikianalia (Spica in Virgo) and then we get to Me’e (Corvus) from there we can go straight down to Hanaiakamalama (Crux/Southern Cross), so the backbone is complete covering north to south above us in the night sky. Hokupa’a (Polaris) is

cont'd >

ISSUE 2, 2023

almost exactly the zenith star of 90° North (directly above the North Pole) making it seem “fixed” (the meaning of Hokupa’a in Olelo Hawai’i). When the star disappears below the horizon, one knows that they have passed the equator and are in the Southern Hemisphere

The other stars are definitely not fixed in the night sky though! A couple hours into evening watch and the star line Manaiakalani displaces Iwikuamo’o above us, which is now setting in the west. This star line consists of Huinakolu (“The Navigator’s Triangle”), which consists of the stars Pira’etea (Deneb in Cygnus), Keoe (Vega in Lira) and Humu (Altair in Aquila) and Ka Makau Nui O Maui (“Maui’s Big Fishhook”) known as the constellation of Scorpio. It is nothing short of magical to see Maui’s hook; pulling the “big fish” (the Milky Way) all the way through Pira’etea across the night sky (in other Pacific Island cultures this is same; they speak of a long shark in Aotearoa New Zealand and of a long sea-monster in Rarotonga; some other sources say that Maui isn’t hooking the Milky Way but Pimoe a magical Giant

by Sil Kiewiet de Jonge

Trevally which would be Sagittarius in the West) In mythology Maui uses his powerful hook to lift lands from the sea and bring the islands of Hawai’i closer together. When the watch switches from evening to dawn at 0100 we see the third star line appear, Ka Lupe o Kawelo (Kawelo’s Great Kite), which consists of connecting the western constellation of Pegasus to the sea monster (Cetus) and the southern fish (Pisces Austrinus), south all the way to Iwa Keli’i (The Frigate Bird, Cassiopea in the West) which will point north Ke Ka o Makali’i (“the Canoe Bailer of Makali’i”) cannot be seen this time of the year as it is hiding behind our big lovely day-star (the Sun).

I understand me explaining this to you, feebly attempting to communicate what these star lines look like and mean, from one side of the world to another, may not be of much use to your spacetime.

However, they have provided me with a profound sense of place both physically in the universe and the world, but also to our mutual mother earth and my life in this spacetime. These star lines are a miracle in one more way: they come from peoples who have been subject to colonization and imperialism My ability to learn them is a direct result of their fight to keep their culture and heritage alive in the face of colonization and all the horror that

cont'd >

Hokule’a is Hawai’i’s zenith star, which means it rises directly above Hawai’i.

has come with it and the wake of terror it has left behind It goes without saying that learning these star lines is a privilege and that there is something about them that I (a kid from the other side of the world) may perhaps never truly understand or be able to connect to, but to me, that is what makes them so much more special.

by Sil Kiewiet de Jonge

Further Reading

Bishop Museum. “Sky Maps.”

https://www.bishopmuseum.org/skymaps.

‘Imiloa “September 2023 Sky Watch ”

https://imiloahawaii.org/sky-charts.

Polynesian Voyaging Society “Hawaiian Star Lines and Names for Stars ”

https://archive hokulea com

The Forgotten Realm’s Dilemma

t the bottom of the sea lives a potato. Well… a ferromanganese nodule, composed of some of the earth’s most valuable metals, which has taken millions of years to form into the appearance of a potato. Suddenly in the black depths of the sea, a blinding and deafening machine comes along and scrapes the potato from its residence for the past millennia. The potato is plucked out of the dirt and muck and brought up to the dry side to be melted down and twisted into a battery to live in your car or your phone. The glorious natural processes of the last era are erased and thrown into a landfill within a year or two

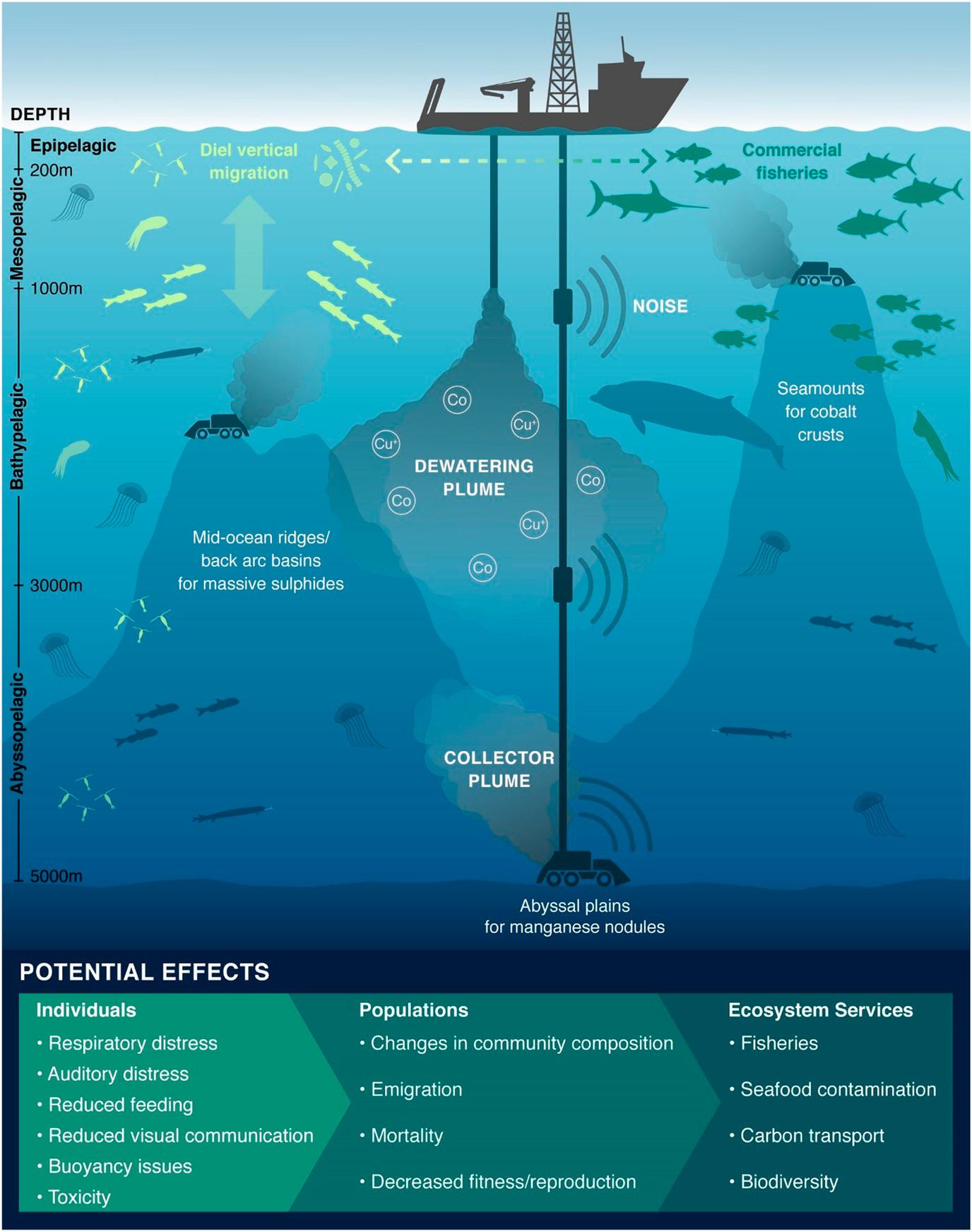

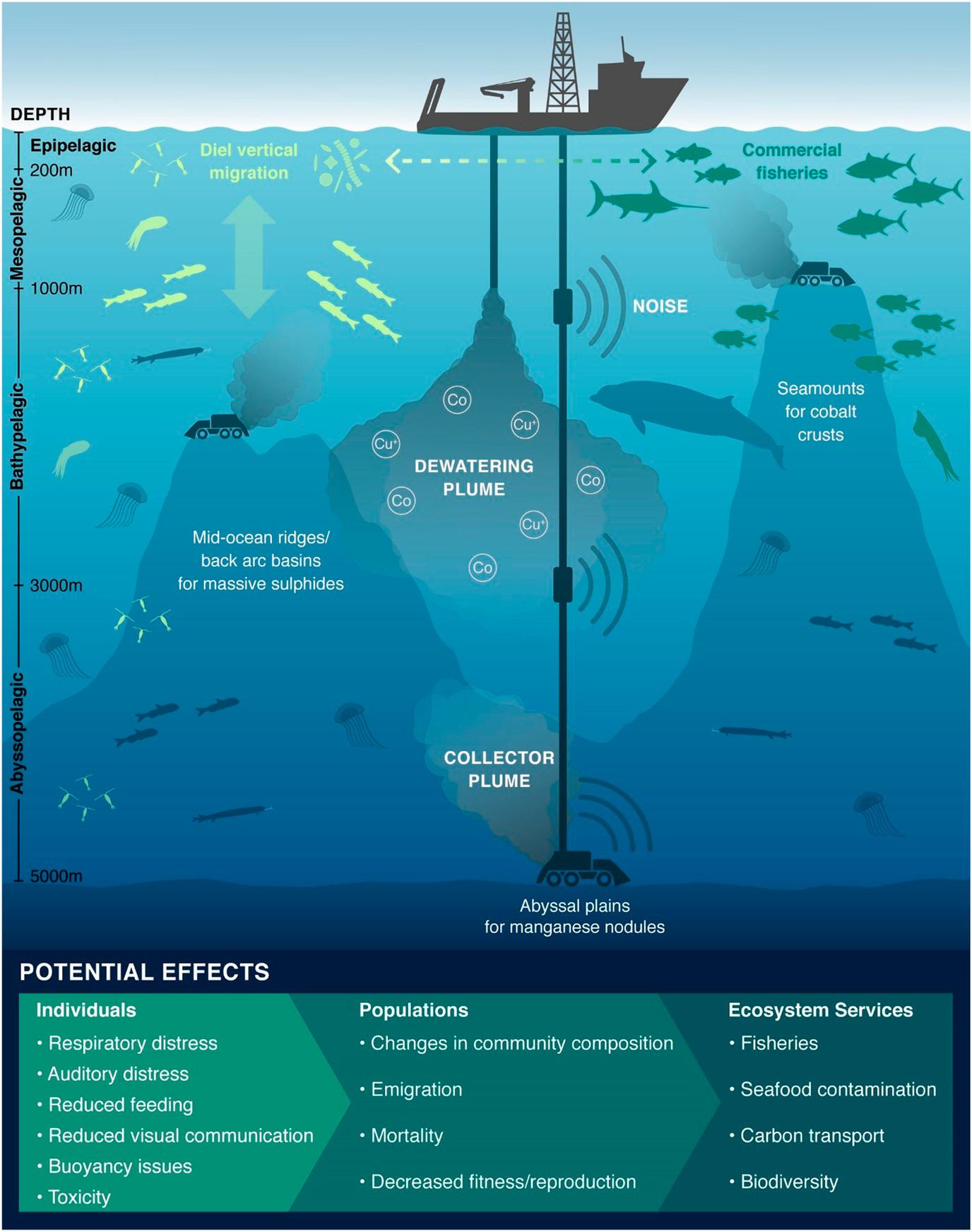

Deep sea mining (DSM) is the extraction of valuable metals from the seabed in the form of nodules, cobalt rich crusts, or massive sulfides. Each of these forms of metal deposit requires intense and expensive extraction methods due to the difficult access of the sea floor.

by Hallie Rockcress

by Hallie Rockcress

The mining operations send remote operated vehicles to search and gather deep sea deposits between 200 to 6,000 meters below the surface. However, due to the unreachability of these locations it is a widely unexplored resource, despite its discovery over 150 years ago by the HMS Challenger There was a movement in the early 197080s to explore this resource, but in 1982 the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) established the International Seabed Authority (ISA) to regulate and monitor these processes After that, interest dwindled, and research plateaued due to the complexity of

cont'd

>

A

ISSUE 2, 2023

A deep-sea mining vessel, the Maersk Launcher, from The Metals Company in the Pacific Ocean The craft can begin commercial operations for exploiting deep-sea deposits as soon as 2024

the operation. And due to the lack of interest in commercializing the resource, there is limited research completed about the ecosystems that exist and what harm might occur from DSM.

From the limited research completed, however, there is one thing to be true: the ocean floor moves slowly The animals move leisurely, if at all, to find food or a mate. The nodules take more than millions of years to form. So when dramatic change occurs, it is essentially impossible for the system to return to a stable state. A study in 2018 analyzed the remnants of a mining site from 1978. The researchers found perfectly preserved tire tracks left from the machinery that had a millimeter of dust and the only change is the absence of all life. Even then scientists aren’t sure about where or what the life of the seafloor is. Many theorize that jellyfish, sponges, and other creatures use the deposits as habitation and have found decreased levels in reproduction where the deposits have been removed.

The region below 200 meters water holds 95% of the world’s ocean and is the biggest habitat on the planet. There are more places to be concerned than just the bottom, such as the midwater ecosystems A study completed in 2020, looked at the potential effects of the mining machines along midwater

by Hallie Rockcress

ecosystems. Concerns arose from the ROVs that sort the deposits from the surrounding dirt sending plumes of ultrafine sediment into the entire water column. The dust particles have caused respiratory problems for many organisms and caused temporary blindness from the cloudiness combined with the extremely bright lights of the machinery. Many marine mammals have been documented to struggle with hunting or finding mates. Many of the studies done to date evaluated the potential effects of mining operations, since there are no exploitation permits allowed until later this year.

This past spring the Biden-Harris Administration announced its goal to transition fifty percent of new vehicle sales to be electric by 2030 This comes as part of the Investing in America Agenda, which funds private and public sectors to invest in EV development. Despite its good intent, this goal puts pressure on the depleted terrestrial metals industry, so companies are looking to DSM for a quick fix solution rather than

cont'd >

From the limited research completed, there is one thing to be true: the ocean floor moves slowly.

“Mining-generated sediment plumes and noise have a variety of possible effects on pelagic taxa Organisms and plume impacts are not to scale ” (Amanda Dillon, graphic artist; from Drazen,

et al )

evaluating the state of the circular economy The ISA include 167 member states and the United States currently has not ratified the UNCLOS, despite the current administration's goal to strengthen "secure access to critical mineral supply chains."

These announcements come at a delicate time due to the ISA’s time limit on Mining Codes running out. The Mining Code refers to the regulations under which companies and their sponsor country can apply for exploitation permits and provides guidance on well-managed mining activities. In the summer of 2023, the ISA legally must start accepting applications for extraction permits if there were mining regulations or not. Currently, there are none. Prior to July the ISA was only able to allow exploration permits and no environmental regulations set for evaluation. Furthermore, there are many efforts to protect our oceans, like the Ocean Climate Action Plan, but these rulings neglect the rising implications and dangers of extraction projects.

However, a circular economy would be a reboot of the current economic model under capitalism. It is common economic thought to regard the Earth’s resources as infinite and replaceable by human capital, which is without reasonable planetary boundaries. This

by Hallie Rockcress

misinformed advice leaves policy makers ignorant of current climate calamities Rather than looking into the unknown and therefore destroying an ecosystem that is far removed from anthropogenic change, we need to reevaluate what we already have. A European Commission initiative from 2015 adopts the practice for a circular economy of rare metal materials. The initiative focuses on recycling and changing consumer mindset on modern technology. There are current projects that look into landfill mining to extract disposed lithium batteries and grant them a second or third life.

If projects in DSM continue, there needs to be an equal investment from companies and countries into research. There is a need for

cont'd >

Asst. Scientist Carly Cooper (yellow helmet) and student Sam Barresi (orange helmet) help deploy the CTD carousel aboard Seamans

renewable energy, and if DSM is our only way of large-scale obtainment, then there are necessary measures in order to protect our forgotten realms. Research vessels like the Robert C. Seamans can continue to do independent research to create foundations for further analysis on the effects of mining on the water column and organisms in the midwaters.

Although we only sailed a few hundreds miles to the west this past summer, other SEA voyages have sailed over the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) The CCZ is the most surveyed region for DSM and currently has seventeen permits for exploration. Many policy experts engage with integrated ocean management, which calls for harnessing knowledge, increase stakeholders’ engagement, and establishing better, more secure private public partnerships. A healthy and resilient ocean is the goal for all, but where should we stand in the destruction of something we don't understand?

Further Reading

Jan-Gunnar Winther, et al., “Integrated Ocean Management for a Sustainable Ocean Economy,” Nature Ecology and Evolution 4 (2020): 1451-58

K.A. Miller, K. F. Thompson, P. Johnston, and D. Santillo “An Overview of Seabed Mining Including the Current State of Development, Environmental Impacts, and Knowledge Gaps,” Frontiers in Marine Science 4, no. 418 (2018): doi 10.3389/fmars.2017.00418

“FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Announces New Private and Public Sector Investments for Affordable Electric Vehicles,” The White House (April 17, 2023): https://www whitehouse gov

by Hallie Rockcress

Energizing the Pacific Islands

ormer President of the United States, Barack Obama, said during the 2014 U N Climate Summit, “The nations that contribute the least to climate change often stand to lose the most.” This is the case of the island nations of the Pacific Ocean, whose low-lying islands with little to no elevation are already seeing the effects of global warming in the form of rising sea levels claiming their lands and spoiling their already precious supply of fresh water. The consumption of fossil fuels and their carbon emissions are the largest contributor to rising oceanic and atmospheric temperatures. However, the Pacific Island Nations have contributed next to nothing to this increase. In terms of energy use and infrastructure, the Pacific Islands remain one of the least developed regions in the world While there are high amounts of

by Caleb Fineske

Fvariation as to the amounts of people with access to power, dependent on the island nation, overall, according to the World Data Bank, only twenty percent of homes have electrical power and around only half of the population have access to electricity at all. If the majority of the governments and citizens of the Pacific Island Nations want industrialization, or at least, better access to electricity, why is it taking so long to do so?

Why has electrification not begun?

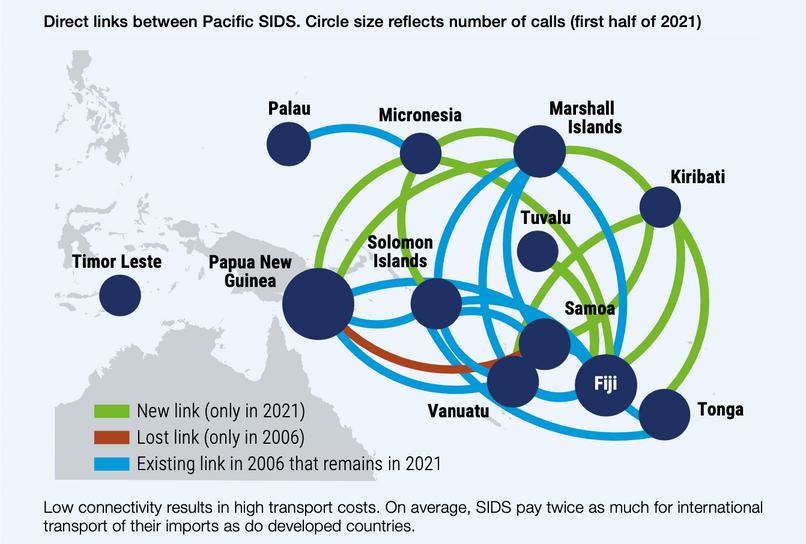

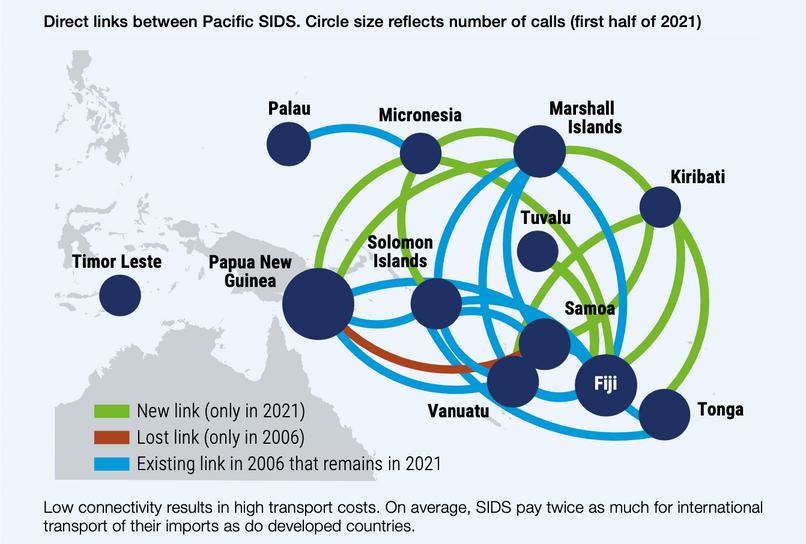

From my personal research, information has been incredibly hard to come by, which may act as a symptom of the broader issue of the lack of implementation of power systems in the Pacific Islands. PostCovid, the amount of research regarding electrification diminishes significantly. Furthermore, it was remarked by the 2022 U N Review of Maritime Trade that trade routes and distribution of goods to the Pacific Islands has decreased continually since 2006.

cont'd >

ISSUE 2, 2023

Beyond the lack of easy-to-find online reporting on current energy information, the Pacific Island Nations have a unique set of barriers towards development of a broader energy grid and implementation of electricity to the majority of their inhabitants, predominately due to their population and land geography. The Pacific Islands are some of the most remote locations on the planet, with expanses of ocean up to thousands of miles between both each other and the nearest continental landmasses They are further marked by being some of the lowest across the globe in both total population and landmass. Because of their remote nature, lack of industrial infrastructure, and low populations, the inhabitants lack the

by Caleb Fineske

capital to produce technical goods and other items This leads to very high percentages of importation for the goods they lack the infrastructure to produce, as well as one of their largest imports, which is petroleum-based fuels. Despite this high need of imported goods, the majority of the Pacific Island Nations are among the least connected countries in terms of shipping routes, according to the 2022 U.N. Conference on Trade and Development The main points of the economies of the Pacific Islands are much the same amongst them, being dominated by fishing, agriculture, and tourism, all of which take fuel to power them. Many inhabitants of these nations also engage in subsistence-based

cont'd >

“Liner Shipping Connectivity in Small Island Developing States (SIDS) in the Pacific” UN Review of Maritime Transport (2022)

economies, resulting in the average income per capita of the fourteen Pacific Island nations, such as The Solomon Islands and Kiribati, to be nearly $3,600 USD according to the World Data Bank’s report in 2021. With these low incomes in mind, as well as the lack of a preexisting industrial infrastructure, the governments of these many island countries have had trouble garnering the funds to create nationwide energy grids. The startup costs of importation and setup of these numerous delicate technical components would be quite the financial undertaking in any global location, let alone across the thousands of islands that make up this region.

While some energy infrastructure exists across the many islands and nations, they are usually focused on single islands with the highest populations. Prime examples of this are Nauru and Tuvalu, single island nations with populations of roughly ten thousand each; another is Kiritimati Island in Kiribati. Since they each have a high population density compared to other island nations or other islands within their own nation, efforts to provide energy across them have been quite successful, with all inhabitants having access to electricity. However, as the scope is widened to the many rural areas and less densely inhabited islands in these

by Caleb Fineske

nations, the power grids and access to electricity drastically worsen

Benefits of Renewables

The lack of infrastructure pertaining to energy systems in the Pacific Islands definitely has its silver lining. In a world where developed and developing nations are increasingly reliant on fossil fuel consumption to power their every aspect, the ability to start fresh, unafflicted by reliance on one type of energy source has numerous merits.

grid.

Many nations have the base of their electrical grids firmly rooted in power generated via fossil fuels, resulting in their continued use The process of shifting a grid to include or become based in renewable sources is a long, arduous undertaking. However, under the circumstance that is met by many of the Pacific Island Nations, they have the opportunity to start anew and bypass the adjustment costs of transferring an energy grid. With an initial start with renewable energies, they might reap the most benefits

cont'd

>

Pacific Island Nations...have the opportunity to start anew and bypass the adjustment costs of transferring an energy

available too; the earlier renewables are implemented, the sooner one does not have to pay for fuels, the sooner the renewable energy source begins to pay for itself and cover its costs. This concept is increasingly important in the context of the Pacific Islands, where according to Cole & Banks in 2017, one of the largest national expenditures is fuel imports Through the implementation of renewable energies, importation costs would be reduced significantly, allowing the development of numerous other industrial and social infrastructures such as improvements in hospitals, creation of plants to produce exportable goods, and the ability to create their own technological goods. Implementation of renewable based grids will also give the island nations a sense of energy independence, leaving them less afflicted by the increasing prices of petroleum fuels. Furthermore, due to the widespread nature of the population of the Pacific Island Nations in rural settlements across the many islands of which they are comprised, independent grids of renewables will be much easier to maintain as the only time necessary to interact with them is for general maintenance instead of relying on infrequent resupplies of fuel.

What does the future hold?

The implementation and utilization of renewable energies is a widespread desire across the Pacific Island Nations. For example, by 2020, Niue, Tuvalu, and The Cook Islands aimed to have all their current energy be replaced by that of renewable sources, and numerous others set lofty goals of renewable energy implementation by 2020 as well. Further research must be conducted to determine the extent that these targets were met, however, the intention exists. National governments also have created subsidization plans for rural electrification In Fiji, there exists a plan where the government can pay up to ninety-five percent of the costs of grid expansion. However, this expansion of a renewable power

by Caleb Fineske

cont'd >

A rural view just outside Savusavu, taken from the back of our tourist truck

grid is marked by incredibly high start-up costs To offset these costs, many other nations, predominately the United States, offer money in the form of foreign aid and grants that are dedicated solely to the creation of renewable energy systems amongst the islands, according to Alexander Keeley in 2015

Final Thoughts

The Pacific Island Nations have a unique opportunity to become the first developing region to be powered by renewable energies. Through the implementation and basis of grids in renewable energies, it seemingly provides the answers to give these nations access into global market and make major strides in their own technological development. As said during the United Nations Climate Summit in 2014, renewable energies will “Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all."

by Caleb Fineske

Further Reading

M. Dornan, “Access to Electricity in Small Island Developing States of the Pacific: Issues and Challenges,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 31 (2014): 726-735.

A R Keeley, “Renewable Energy in Pacific Small Island Developing States: The role of International Aid and the Enabling Environment from Donor’s Perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production, 146 (2017): 29–36

Shifting Blue

ime for many of us feels fluid while out at sea, sometimes speeding up and sometimes feeling extremely slow. We end up in our own bubble of watch rotations and meals and our days flow into one another almost seamlessly, each of us following our own schedules within the greater group one, trying to sleep, trying to be present, trying to find time for projects, some relaxing, and spending time with each of the interesting and wonderful people we continue to get closer and closer to. As we change time zones and cross datelines, it’s an extra reminder of time passing, our physical place on the globe, and how things shift and are transient.

A lot of our days follow the same pattern, the things and people we look at are constant enough that slight changes are more noticeable than at a lot of other times in our lives. One of the things I am hyperattuned to while at sea is the constantly changing colors in the

by Hannah Gerrish

sea and the sky – always the same and yet always shifting. Here in the middle of the Pacific on a sunny day the ocean is probably the purest blue I’ve ever encountered. As someone who is accustomed to the green-tinged and often silty glacial waters of the higher latitudes, this bright dark blue caught me off-guard when I first experienced it.

When it’s not too choppy, look down. The sun sends visible beams into the blue, which seems almost iridescent The water is so clear that you can’t really gauge how far down you’re seeing you don’t know what to look at because it’s all just there, deep, and bright, and beautiful. When we do deployments you realize that that indescribable depth to the color is in fact due to the depth of the water; anything that we put below the surface becomes a brilliant shade of turquoise. This turquoise isn’t at all teal-y, nor is it aquamarine. It is genuinely the most pristine blue turquoise I can think of, an unreal color that might look fake if you depicted it in a painting as how it actually appears. Now look up

T

cont'd >

ISSUE 2, 2023

and out. It’s still sunny but your perspective has changed Now you see the surface waves, ripples of movement and color that are never still. We see our first hints of shadowed blue and within it just barely perceptible a ghost of purple. Farther out we reach the dark line of the horizon, also never quite perfect because if you stare hard enough, you’ll see the minute undulations of the persistent ocean swells breaking up even that apparently rigid constant.

Here you meet the sky. At the horizon it’s usually hidden in a low band of clouds, their bases out of reach below your line of sight, their tops billowing into evolving shapes over the light, almost hazy, low sky blue, like a light blue garden flower. Up the gradient you go into darker blue A sky blue, not so different from a clear day at home, just brighter. The sun burns high here, and the light seems to come from all around, reflecting off the sea, off the deckhouses, off each other The sky glows, we glow, and we squint, sometimes even through our sunglasses.

A few hours later the light dampens as the clouds come over to us. They’ve built up and surrounded us with fantastical shapes and then cover the sky. We have a reprieve from the sun’s attack and instantly everything changes. That imperceptible purple in the water

by Hannah Gerrish

now feels more tangible as the deep bright blue begins to feel as though inside it might hold some lavender. The waves become a bit more steely and the chop has an element of grey.

It’s nothing compared to the dark grey curtain that is bearing down on us, however. Down out of the moody navy-grey bottom of a fastapproaching cloud streaks the rain that forms a seemingly solid mass As it comes near, we can see that the line where the curtain meets the water has gone hazy, it has lightened, and then we can hear it coming, whooshing over us and enveloping us in white noise and water The air has cooled and though the rain is warm it’s a wonderful refreshing shock that will last beyond the squall as our clothes stay wet for a moment and give us a reprieve from the hot sun that will soon return. Looking around again as the rain beats down it’s as though we’ve been dropped into a painting. That surface haze softens the edges of everything, the stark saturated colors of tropical sun are reduced to gradients of blues and greys, of

cont'd >

The sky glows, we glow, and we squint, sometimes even through our sunglasses.

slates and steels.

And then it's over Contrast is back and now we can see all those blues at once. The squall is receding with its moody and menacing presence; the myriad kinds and shapes of clouds adorn the sky once more. They are gradients upon gradients, reflecting the warm colors of the sun while retaining their cool blue-grey depths all upon that bright background sky. And the water, again, goes back to being tantalizing. It hints at its depths and invites you in. It sparkles and shimmers and dances with shades and hues and impossible things.

You can notice all these things but describing them is a whole other matter. And what about representing them in art? Trying to paint them? To photograph them? How do you capture something that is never still, something so complex, so transient.

The ocean is often referred to as the ‘big blue’ - both an apt description and drastically undermining the complexity of what we can perceive if we just pay a little bit of attention. Furthermore, at each day’s beginning and end we get a brief new magical palette. We come up from below and out of the lab and our projects We call up our shipmates from the galley and the engine spaces and tumble out of our bunks for sunrise and sunset appreciation time - brief daylight

by Hannah Gerrish

moments when the sun is a joy rather than a struggle. For a while the light turns pure gold Next the sky can be cotton candy or on fire. We revel, both in silence and with giggles and laughter, with smiles on our glowing faces and the wind in our hair, some with arms around each other and some taking advantage of reflective time for self Together, we share these moments, this little bit of the blue world, that keeps moving around us, and with us.

Beyond the Goop: Tuna Larvae and the Pursuit of Sustainable Fishing

It’s a little after midnight on deck of the Robert C Seamans. The assistant scientists are in the wet lab They stand over a small mesh sieve sifting through a pile of pink and blue planktonic goop, the result of a half hour long zooplankton tow using the neuston net Working meticulously with tweezers they hold up what appears to be a wet gray string no longer than a few millimeters They have found something they have been searching for This wet gray string is a larval fish, one of the first life stages of the albacore tuna

With its ecological, economic, and cultural significance for people, tuna represents an important species in marine ecosystems. Yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacores), skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis), and bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) species, among others, occupy predominant positions in the pelagic food chains, exerting top-down control on prey species. As a multi-billion-dollar

by Elijah Busch

industry, tuna fisheries contribute significantly to global food security, international trade, and the livelihoods of millions of people worldwide. However, the sustainability of tuna populations has become a pressing concern due to the combined pressures of overfishing, habitat degradation, and inadequate management practices of some species of tuna. The vast majority of these larval fish will never make it past the larval stage.

cont'd >

ISSUE 2, 2023

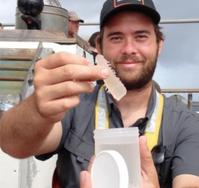

A petri dish with larval fish from a neuston net deployment in the American Phoenix Islands near one of the seamounts. The sample is about to be bio-volumed and placed in a small jar of ethanol for later lab research

Amidst the multifaceted discussions about tuna conservation and sustainable fishing practices, my personal connection to the subject takes on a practical dimension. As a committed pescatarian throughout my life, and with both my fathers sharing the same dietary preference, our household places a strong emphasis on minimizing our carbon footprint. We prioritize locallysourced seafood and consciously avoid farmed fish, aligning our choices with the broader mission of responsible consumption. Yet, a notable exception exists in our culinary repertoire – the indulgence in an ahi tuna poké bowl. (Ahi is usually yellowfin or bigeye tuna.) However, this delight prompts a crucial inquiry: How does this prized tuna journey from its aquatic habitat to becoming a delectable centerpiece in a vibrant poké bowl?

Tuna fishing is conducted by various vessels around the world, ranging from small-scale artisanal boats to large industrial fleets The fishing methods employed vary depending on the target species, fishing location, and technological capabilities of the vessels. Understanding these fishing boats and methods is crucial for effective fisheries management and conservation.

Purse seining vessels are commonly used in large scale tuna fishing operations. These vessels deploy a large net called a purse

by Elijah Busch

by Elijah Busch

seine around a school of tuna, encircling them. The net is then closed at the bottom to capture the tuna Purse seine fishing is particularly efficient in catching species like skipjack and yellowfin tuna which often swim close to the surface in large schools.

Longline fishing involves setting out a main line that stretches for several kilometers with multiple baited hooks attached at regular intervals. This method targets various tuna species including high value species like bluefin tuna. This method of fishing can be harmful to seabirds who can get tangled up trying to eat the bait from the hooks. It also can be extremely detrimental to other marine life if the long line breaks and entangles other species.

Fish Aggregating Devices (FADs) are floating structures deployed in the ocean to attract tuna and other pelagic species. FAD fishing involves

cont'd >

The longline fishing boat Shan Shun which the Robert C Seamans saw and tried to contact via radio (See image below.)

setting nets or fishing lines around these devices to capture the aggregated fish. While FADs can enhance fishing, they also increase the bycatch of non-target species and contribute to ecosystem impacts.

Pole and line fishing is a more sustainable and more selective method for catching tuna. This involves using baited hooks attached to poles, each is individually deployed into the water. This style of fishing is more expensive and takes longer to catch the same number of fish as other techniques, however it

does result in reducing bycatch and minimizing environmental impact