3 minute read

Tackling Climate Change - the part the ocean plays

John Baxter Seabird Centre Trustee John Baxter addresses our current global climate emergency.

Advertisement

Over the last 180 years or so the emissions of carbon dioxide (and other greenhouse gases) into the atmosphere through our burning of fossils fuels, cement manufacture and intensive agriculture have increased rapidly. What is not so well known is the role that the ocean has played in mitigating the impacts of such emissions as a major heat and carbon reservoir. For example, if the same amount of heat that has been absorbed in the top 2000m of the ocean over the last 60 years had gone into the lower 10km of the atmosphere then the Earth would have seen a warming of 36°C. In other words, much of the world would have become uninhabitable.

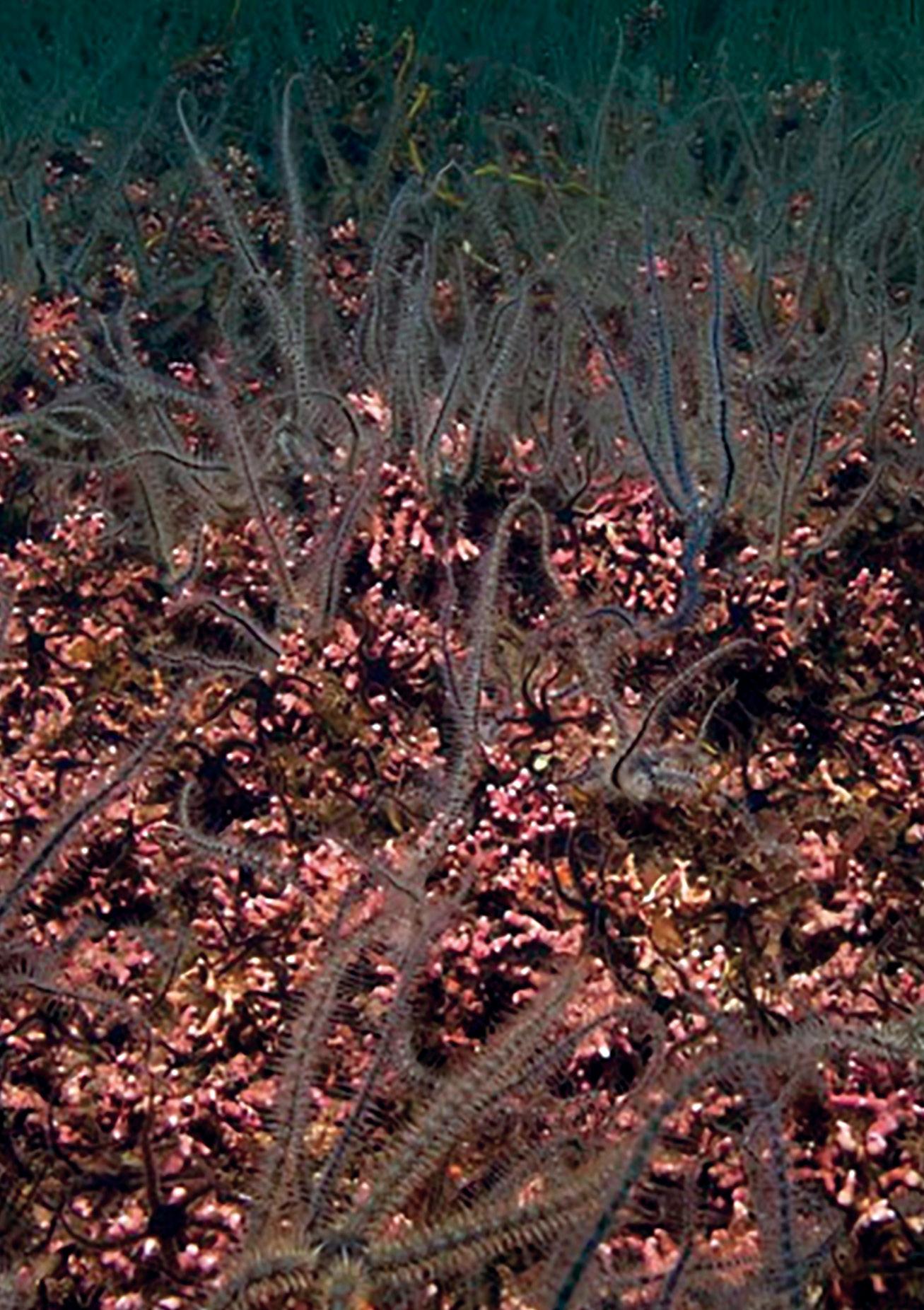

Maerl bed.

The ocean has been our greatest friend and saviour and yet we continue to abuse it, and as ever it comes at a cost. As the ocean warms it affects the distribution of species, the more cold-water species moving northwards and deeper in search of cooler water. As a result, those species that depend on them for food, such as many seabirds that rely on sand eels have to travel further to find food and face a greater struggle to successfully rear their chicks. As the ocean absorbs more carbon dioxide it becomes more acidic and this puts greater stress on many organisms, especially those with calcareous skeletons, including many of the microscopic planktonic algae (the phytoplankton) which form the base of all marine food webs. As the water warms oxygen is less soluble leading to reduced oxygen levels in the water – deoxygenation – putting greater stress on many marine species and results in some parts of the seabed and water column becoming uninhabitable.

Despite all these stresses the ocean continues to give – but for how long? In addition to absorbing vast amounts of heat and greenhouse gases it is now becoming apparent how the ocean is a vital carbon store much like the forests and peatlands on land. This marine carbon is known as ‘blue carbon’.

The ocean both captures carbon and stores it. The extensive kelp forests that fringe much of Scotland’s coast capture large amounts of carbon through photosynthesis. Some of this is recycled by grazing animals etc., but some kelp detritus is buried in the sediments and locked away. Other seaweeds also contribute to this process including ‘maerl’, this is a red seaweed with a calcareous skeleton that lives in relatively shallow areas with a bit of a tidal stream. It forms thick beds with a thin veneer of live maerl on the surface and then dead deposits beneath, akin to the peat deposits beneath the live sphagnum mosses. From carbon dating of the maerl in cores taken from one bed in Orkney we know that maerl has been trapping and storing carbon for at least 4000 years and probably longer. But these habitats and carbon stores are themselves under threat, rising temperatures may affect the distribution of kelp, ocean acidification may start to affect the calcareous skeleton of the maerl.

Other habitats whilst not directly capturing carbon dioxide act as vital sinks for carbon stores. The deep muds on the sea bed of many of Scotland’s sea lochs are a very important carbon sink. Latest estimates suggest that compared to an equivalent area of peat bog the muds store five times more carbon. Further research is underway in Scotland to gain a better understanding of the scale of our blue carbon resource. It has yet to be fully quantified but from the initial estimates it is clear that it is significant. What is most important is that we ensure that, now we are better aware of the scale of the resource, we do everything we can to protect it.