Design Theories and Neuroscientific Insights: The Shortcoming of Design Intentions

Siyuan Yang I a1873488 I G1.7 I Design Research“The discourse shaping modern design remained full of permanent paradoxes.”

-Beatriz Colomina & Mark Wigley

“The discourse shaping modern design remained full of permanent paradoxes.”

-Beatriz Colomina & Mark Wigley

Traditional design theories have long shaped architectural practice, focusing on aesthetics and functionality. However, recent neuroscience advancements reveal how cognitive and emotional responses to design elements challenge these conventional approaches. I argue that the long-established practice of conceptualizing design by design intentions often misaligns with how the human brain experiences spaces.To create environments that genuinely support well-being and functionality, I further argue, architects must integrate neuroscientific insights into their design processes. This integration bridges the gap between theoretical principles and the cognitive realities of human experience, ensuring that architectural designs enhance, rather than hinder, human well-being. (97 words)

For a long while, traditional design theories have determined and monopolized architectural practice, drawing attention to aesthetics and functionality. However, up-to-date discoveries in neuroscience have now challenged these traditional techniques by illuminating the cognitive and emotional responses of humans to design elements. I argue with conviction that the long-standing practice of conceptualizing design based solely on design intent is often inconsistent with how the human brain experiences space. Current architectural design in many cases does not adequately take into account the cognitive and emotional imperatives of human beings, rendering the effect of the design disconnected from the tangible experience of the user.To facilitate the creation of environments that credibly advance wellness and functionality, architects will have to absorb the insights of neuroscience into the design journey.

Such integration is proficient in closing the divide between theoretical concepts and the experiential reality of human interaction, also guaranteeing that architectural design promotes rather than hinders human health.This essay will exploit the shortcomings of design intent, focusing on the misalignment between architectural practice and perceived reality, and positing ways in which design methods can be optimized via the amalgamation of neuroscientific insights to achieve the potential creation of architectural spaces that are more responsive to the needs of human beings.

‘The discourse shaping modern design remained full of these permanent paradoxes.’It reveals several core contradictions in modern design, inparticular the tension between functionality and humanization. In his 1926 review,Adolf Behn indicated that if designers focus excessively on mechanical logic and functionality, this will eventually lead to buildings becoming anthropomorphic, resembling human forms.1 Stated otherwise, designs that attempt to dehumanize become more human.2 Conversely, designs that claim to be centered on the “human will” often result in standardized architecture that is inhumane. This duality reveals an impending dilemma in modern design. Bain further clarifies that from the inaugural tools and shelters, humans have not only settled for function, but have also imbued their creations with elements of entertainment and beauty.

This, it is shown, is an artificial blurring of the veil between tools and plays. Behne, he concluded that it is entertainment that produces a genuine form, rather than nonpure function. Healso contended that pure functionalism therefore fails to generate appeal, and that attempts to segregate function and from entertainment are therefore misguided. In Behne’s view, those who purportedly proclaimed to be pursuing pure functionalism are not factually pursuing functionality itself but are attempting to reshape humanity. Functionalism becomes a vehicleto enhance, strengthen and sublimate the human experience. In functionalist design, every end that is fulfilled is a tool towards the creation of a more refined human being.3As a result, modern design oscillates between being faithful to human demands on the one hand, and negligence and reconceptualization of the human being on the other.

In this journal, I will recap a selection of traditional design theories that have prolonged guided the practice of architecture. These theories offer guidelines that influence the design and utility of architectural spaces, these theories are broadly applicable and have extensive uses. Examples include symmetry, proportion and minimalism. However, when discussed through the lens of neuroscience to analyse the subconscious responses of humans to these design concepts, the argument is that these elements are oftentimes not adequately considered interms of how they affect human cognition and emotion.

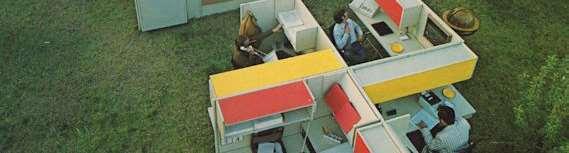

For example, in Jennifer KaufmannBuhler’s book” Open Plan:ADesign History of theAmerican Office”, it is argued that open plan office design is a staple of modern architectural theory, designed to promote collaboration and flexibility. However, large open areas with minimal partitions, which should be advantageous design elements, overstimulate the environment, leading to sensory overload and negatively impacting cognitive function and emotional well-being.4 As more and more research emerges on the sensory feedback generated by physical spatial interactions, it becomes especially paramount for architects to be aware of the underpinning logic and to utilize itin the ongoing exploration of design thinking. Owing to my research, I have a desire to contribute to the exploration of how architects can incorporate neuroscience insights into architectural design to foster environments that are more conducive to human perceptual,

cognition, and well-being. Such integration is critical to cultivate spaces that genuinely celebrate and champion human health and function, bridging the gap between theoretical design principles and the perceived reality of human experience.

As Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley discuss in *Are We Human? *, “the discourse shaping modern design remained full of permanent paradoxes.”This underscores the necessity of aligning architectural practices with cognitive realities to expand and refine environments that authentically enhance human performance and proficiency, welfare and prosperity.

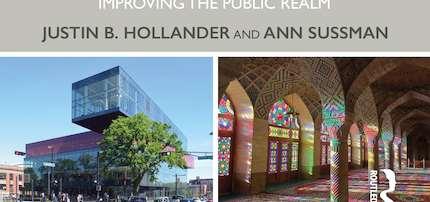

“Welcome toYour World” by Sarah Williams Goldhagen discusses the detrimental effects of poorly designed environments on cognitive functions and social interactions. Goldhagen’s analysis of Jean Nouvel’s Serpentine Pavilion illustrates how design features like sharp angles and intense colours can induce stress, demonstrating the impact of design on discomfort and anxiety.5 “Urban Experience and Design: Contemporary Perspectives on Improving the Public Realm,” edited byAnn Sussman and Justin Hollander, combines neuroscience with urban design using biometric technology and eye-tracking contraption to validate negative responses to sharp, irregular forms in the built environment. This emphasizes the significance of understanding human cognitive and emotional reactions to architectural elements. 6 “Towards an Urban Regeneration” and the “Residential Design Guide” by Glasgow City Councilcritique grid layouts are be-

coming increasingly rigid and predictable, and if this trend continues to be applied to urban planning, the experience of the inhabitants willlack a connection to nature, which can lead to disorientation and even disengagement from social development.7

This limits the possibilities for community exchange and misses many opportunities for development.8 “Open Plan:ADesign

History of theAmerican Office” by Jennifer Kaufmann-Buhler along with Bodin Danielsson’s study in “Environment and Behaviour”address the cognitive difficulties presented by open-plan office settings with historical context and empirical evidence showing increased stress levels and decreased job satisfaction associated with these designs, aligning with neuroscientific findings on sensory overload impacts.9

Throughout my research process, the selection of material sources as the first step, I expect that this dominant direction is based on the comprehensiveness of the

stability of the solution and strive to be rich in practicability also known as robustness.The first condition of all is the ability to explore in depth the multifaceted perspectives that I am concerned with, that is, the brain fluctuations caused by the architectural elements and the neurological responses of human beings to their environments in the context of urban planning strategies.These sources cover a broad spectrum of topics which collectively deepen my comprehension of how design influences human well-being and societal dynamics. In addition, I have endeavoured to strike a balance in selecting sources that afford both supportive perspectives and critical evaluations of traditional design practices in order to instigate nuanced discussions that effectively address potential biases while considering differing viewpoints.

For example, minimalist design is emphasized on open spaces and clean lines to produce a clean, neat visual effect.This design style can deliver a sense of calm and relaxation because it avoids visual clutter and overstimulation of pertinent messages. In addition, minimalist design often uses neutral tones and natural light, adding further to the serene atmosphere of the space so that people are able to perceive a sense of inner peace and harmony within it. Nonetheless, if it is used overly, such environments may be sterileand cause isolated and uncomfortablefeelings.As demonstrated by neuroscientific research, people are naturally attracted by intricate and diversified environments, stimulating neural activity and boosting welfare.10 Thus, despite visual attractiveness of minimalist design, itneeds to be balanced with factors that offer sensory engagement and comfort.

The 2010 Serpentine Pavilion of Jean Nouvel exemplifies the failure to coordinate conventional design theories with neuroscience insights. In order to evoke the warmth and joys, Nouvel made use of sharp angles and intense red colours to design the pavilion. Nevertheless, such design may make visitors feel stressful and uncomfortable.As indicated by neuroscience, irregular forms and intense red contexts are likely to elevate anxiety and lower cognitive function.11 Contrary to the design intentions of Nouvel, the factors constituting the pavilion may induce physiological stress responses (e.g. improved heart rate), due to the stimulating effects of the colour red and the unsettling nature of sharp angles.This example illustrates the value of gaining an insight into how certain design elements affect human psychology.

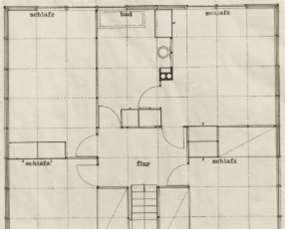

Construction - Weissenhofsiedlung**

The rectangular or square grid is a typical example of pragmatism in design. Prior to digital computation, straight lines and right angles simplified construction and facilitated engineering.Through this method, the process of positioning structural supports and locating rooms and corridors could be simplified. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the grid became more useful with the mass production of standard construction materials. Commercial buildings and contemporary skyscrapers often employ a five-foot gridded module to calculate floor plates and design interior spaces. In large-scale residential projects, the gridalso remains a widely applied template.As early as 1900, the grid had been the favourite modus operandi of architects. Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand developed a

modular square grid system and claimed that a building of any size and complexity could ideally follow this model. Early modernist architects, such as Walter Gropius, embraced this approach for affordable housing projects, such as the Weissenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart, Germany. Gropius used the grid for the floor plans, interiors, and exteriors of Houses 16 and 17, saved construction costs, and minimized manufacturing and transportexpenses by creating smaller individual components that could be transported more efficiently.At the time, Gropius and others like Ludwig Hilberseimer even proposed the grid not just in housing but also in urban planning. According to Hilberseimer, the homogenization of building design through the grid would help modern urban dwellers feel comfortablewherever they went.12

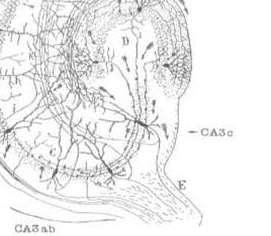

In spite of the undoubted utility of grids, research by cognitive neuroscientist John O’Keefe et al reveals that the cognitive maps used by human brain in navigating space are organic, irregular patterns rather than rigid grids.13 Meanwhile, research on the brain’s internal navigation system by Edward Moser and May-Britt Moser suggests that people’s brains prefer natural and varied environments.14 The brain’s preference for a hexagonal grid system over a right-angled grid indicates that a right-angled grid can bring unnatural and disorienting feelings.15 While creating feelings of isolation and discomfort, such environments could not effectively meet the emotional and social needs of the occupants.

Open-plan offices, which are designed to encourage collaboration and flexibility, are unfavourable for people to do their work best physiologically and emotionally. Despite their intention to enableeffective communication and use of resources, they can also cause sensory overload.As documented in neuroscience studies, open-plan offices can be harmful for cognitive functions and emotional welfare.

Through analysis in Open Plan:ADesign History of theAmerican Office, Jennifer Kaufmann-Buhler highlighted efforts to address noise and privacy issues in openplan office designs. Herman Miller cooperated with the QuickbornerTeam and pioneered solutions such as incorporating partitions and strategic layouts to create partially enclosed workspaces.The aim of these schemes is to establish a balance between solitude and social interaction, ensuring that the office environment is both individually productive and collectively

Sales office for Deering, Millikenand Co. in NewYork City, designedby theKnoll Planning Unit, featuring FlorenceKnoll desks andEero Saarinendeskchairs, 1958.The image illustrates the meticulousoffice planningthat came to define themodern corporate interior. Source: ImageCourtesyKnoll Archive

synergistic.TheAction Office system by Herman Miller included flexible furniture pieces that could provide privacy and support communication between colleagues, as they integrated acoustic panels, while white noise machines were used for volume control. Office design has long been integrated with managerial ideas.The first open-plan offices, represented by Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1939 Johnson Wax building, were built as production halls to bring workers sunlight exposure and stimulate teamwork. However, the enclosed office cubicle became synonymous with dissatisfaction due to visual monotony, noise, interruptions, and insufficient privacy.16 Upon recognizing the need for balance, designers incorporated partitions and strategic layouts to create semi-enclosed workspaces and addressed issues of noise and privacy. In spite of these innovations, it is still challenging to create an open-plan office that supports both collaboration and individual focus. Neuroscience research reveals the source of many open-office

workplaces failing to satisfy workers’cognitive and emotional needs. The human brain receives sensory information all the time and processes input continuously in real-time, which contributes to quick fatigue and overload of stress.17 According to research published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology, open-plan office workers experience more stress and feel less satisfied with their jobs than those who work in settings with closed doors.This is in line with findings that prolonged sensory overload can impair cognitive functions such as memory and attention. Integration of neuroscientific principles into office design (e.g. incorporation of quiet zones and personal workspaces) can be helpful to reduce sensory overload. By providing elements with sensory engagement and comfort, such as natural light, plants, and sound-absorbing materials, architects can create environments that better support cognitive function and emotional health.18

In conclusion, the explanation of the interfaces between architectural design and neuroscience accentuated the urgent desideratum for a holistic perspective on the inception of designed environments. Case studies and examples have surfaced to reinforce the fact that traditional design intent often dismisses the cognitive and emotional priorities of users, culminating in aesthetically pleasing but potentially stressful and uncomfortable environments. Heading into the future, architects must adopt a holistic perspective that contemplates both aesthetic and cognitive dimensions to ascertain that architectural design contributes to well-being, productivity, and overall human flourishing.The successful integration of these arenas has the potential to determine our future residing and labouring environments inherently favourable to our mental resilience and emotional equilibrium in the long run. (2584 WORDS)

Colomina, Beatriz, and Mark Wigley. 2016.Are We Human?. Switzerland: Lars Müller Publishers.

Kaufmann-Buhler, Jennifer. 2021. Open Plan:ADesign History of theAmerican Office. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Goldhagen, Sarah Williams. 2017. Welcome to Your World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives. New York: Harper.

Sussman,Ann, and Justin Hollander. 2021. Urban Experience and Design: Contemporary Perspectives on Improving the Public Realm. New York: Routledge.

Walker, F.A. 1982. “The Glasgow Grid.” InT.A. Markus (ed.), Order in Space and Society (50-60). Edinburgh: Mainstream.

Walker, F.A. 1996. “The Emerge of the Grid: Later 18th Century Urban Form in Glasgow.” In W.A. Brogden (ed.),The Neo-Classical Scottish Contributions to Urban Design Since 1750 (57-64). Edinburgh: The Rutland Press.

Danielsson, Bodin C., Bodin, L., Wulff, C., and Theorell,T. 2015. “The Relation Between OfficeType and Workplace Conflict:AGender and Noise Perspective.”Journal of Environmental Psychology 42: 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.04.004.

Harricharan, Sherain, Margaret C. McKinnon, and RuthA. Lanius. 2021. “How Processing of Sensory Information From the Internal and External Worlds Shape the Perception and Engagement With the World in theAftermath of Trauma: Implications for PTSD.” Frontiers in Neuroscience 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.625490.

Sander, Elizabeth J., Cecelia Marques, James Birt, Matthew Stead, and Oliver Baumann. 2021. “Open-Plan Office Noise Is Stressful: Multimodal Stress Detection in a Simulated Work Environment.” Journalof Management & Organization 27: 1021–1037. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2021.17.

1. Colomina, Beatriz and Wigley Mark, 2016,Are we Human, (Switzerland: Lars Muller Publishers), 82.

Colomina, Wigley, 2016, 83. 3. Colomina, Wigley, 2016, 83.

4. Jennifer Kaufmann-Buhler, 2021, Open Plan:ADesign History of theAmerican Office (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing), 50-55.

5. Sarah Williams Goldhagen, 2017, Welcome toYour World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives (New York: Harper), 135-140.

6. Ann Sussman and Justin Hollander, 2021, Urban Experience and Design: Contemporary Perspectives on Improving the Public Realm (NewYork: Routledge), 90-95.

7. Walker, F.A., 1982,The Glasgow Grid, in T.A. Markus (ed.), Order in Space and Society (Edinburgh: Mainstream), 50-60.

8. Walker, F.A., 1996,The Emerge of the Grid: Later 18th Century Urban Form in Glasgow, in W.A. Brogden (ed.),The Neo-Classical Scottish Contributions to Urban Design Since 1750 (Edinburgh: The Rutland Press), 57-64.

9. Bodin Danielsson, C., Bodin, L., Wulff, C., and Theorell,T. 2015.The relation between office type and workplace conflict:Agender and noise perspective, Journal of Environmental Psychology (42): 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.04.004.

10. Sussman and Hollander, 2021, 60.

11. Sussman and Hollander, 2021, 90-95

12. Goldhagen, 2017, 85-87.

13. Goldhagen, 2017, 87-92.

14. Goldhagen, 2017, 68-69.

15. Sussman and Hollander, 2021, 19.

16. Kaufmann-Buhler, 2021, 55.

17. Sherain Harricharan, Margaret C. McKinnon, and RuthA. Lanius, 2021, “How Processing of Sensory Information From the Internal and External Worlds Shape the Perception and Engagement With the World in theAftermath of Trauma: Implications for PTSD,” Frontiers in Neuroscience 15, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.625490.

18. Elizabeth J. Sander, Cecelia Marques, James Birt, Matthew Stead, and Oliver Baumann, 2021, “Open-Plan Office Noise Is Stressful: MultimodalStress Detection in a Simulated Work Environment,” Journal of Management & Organization 27, 1021–1037, https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2021.17.

Figure 1:

The “seahorse” cross section of hippocampus showing a schematization of core neuralcircuitry, as drawn by the Spanish neuroanatomist Santiago Ramon y Cajal (1899).

<https://blog.oup.com/2022/08/from-navigation-to-architecture-how-the-brain-interprets-spaces-and-designs-places/>

Figure 2 :

Gridded Cities: Ludwig Hilberseimer, from The New City.TheArt Institute of Chicago, IL, USA/Gift of George E. Danforth/Bridgeman Images.

< https://www.artic.edu/artworks/101044/highrise-city-hochhausstadt-perspective-view-north-south-street >

Figure 3 :

Grids facilitate construction: Weissenhofsiedlung, House 17 (Walter Gropius), Stuttgart. BauhausArchiv, Berlin,/© 2016Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

< https://mitp-arch.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/otp0mh38/release/1 >

Figure 4 :

Sales office for Deering, Milliken and Co. in New York City, designed by the Knoll Planning Unit, featuring Florence Knoll desks and Eero Saarinen desk chairs, 1958.The image illustrates the meticulous office planning that came to define the modern corporate interior. Source: Image Courtesy KnollArchive

< https://dokumen.pub/open-plan-a-design-history-of-the-american-office-9781350044722-9781350044739-9781350044753-9781350044715.html >

Figure 5 :

Image illustrating the movement of sound in an open plan office from 1975.The drawing is based on the photograph ofAction Office shown in Figure 6 and uses arrows to show sound produced by individual workers bouncing off of acoustic surfaces which absorb and reduce the overall sound. Source: Robert Propst and Michael Wodka,TheAction Office Acoustic Handbook, 31. Courtesy of Herman MillerArchives.

< https://dokumen.pub/open-plan-a-design-history-of-the-american-office-9781350044722-9781350044739-9781350044753-9781350044715.html >

Figure 6 :

Photograph of the interior of Freehafer Hall from 1971. Image illustrates the careful use of partitions to block views and provide modest privacy. See Figure 1 for another view of the original Freehafer interior. Source: Purdue University Special Collections: UA153 Box 1

<https://dokumen.pub/open-plan-a-design-history-of-the-american-office-9781350044722-9781350044739-9781350044753-9781350044715.html >

Adhered to the word limit in the summary and the article.

Inserted the main quote by C+W on the inside of the front cover.

Followed the 5-sentence template in writing of the summary.

Inserted word count of the summary.

Inserted word count of the article.

Adhered to the prescribed number of spreads.

Adhered to the prescribed number of images.

Researched and cited the required number of sources.

Uploaded PDF file on issuu.com and provided active link on the from cover.

Inserted the checklist on the back cover.

Uploaded final PDF file on MyUni and Box.

Uploaded final Black+Blue word file on MyUni and Box.

Student Name: SiyuanYang