8 minute read

LONDON WOMEN'S CLINIC

Innovation in conception London Women’s Clinic, number one IVF centre in London

It has been more than 40 years since the birth of the world’s first ‘test-tube’ baby. While there have been few moments in the fertility landscape more ground-breaking than the arrival of Louise Brown, the advancements of the last four decades have seen a huge change in the way we approach fertility.

Today, around 20,000 babies are born via IVF in the UK alone each year, with rising success rates due mainly to continuous innovation and improvement in areas such as the egg freezing process. A brief glance at the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority’s (HFEA) clinic rankings will show that the number one centre in London is London Women’s Clinic, with a clinical pregnancy rate of 45% for every embryo transferred in women under 35 years of age and 38% in those older.

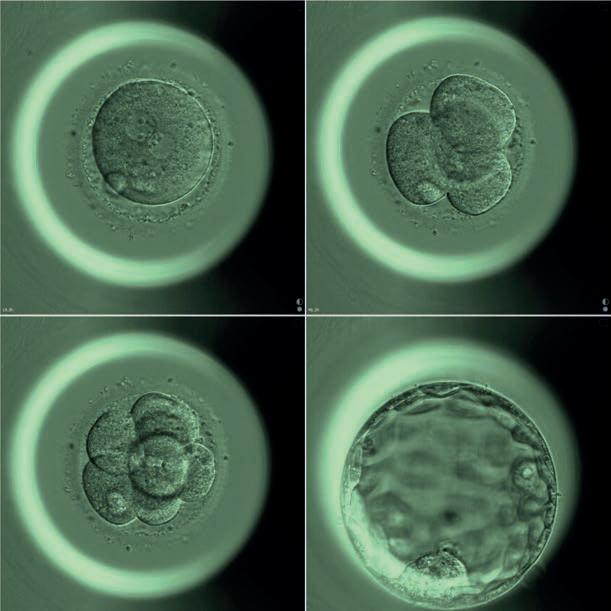

These impressive results – in routine IVF patients – were similarly found in treatments using eggs supplied by a donor. Egg donation is an increasingly common treatment for infertile women whose ovaries are unable to produce suitable eggs, perhaps because of an early menopause or ovarian problem. For these women, a donor egg is their only reasonable chance of having a baby. The increase in the uptake and success of egg donation is due largely to developments over the last decade in the technology used to freeze eggs. The fast-freezing technique of vitrification, developed in Japan in the 2000s, is now used worldwide at clinics including the London Women’s Clinic and its Harley Street partner the London Egg Bank, with remarkable results. Vitrification is the preferred method for freezing embryos prior to transfer and for freezing eggs prior to fertilisation.

For the London Egg Bank, the ability to freeze eggs without damage to their micro-architecture – which was for many years one of the greatest challenges of reproductive medicine – has been the defining principle for its recent range of treatments. Those treatments now include elective egg freezing for the preservation of fertility and the supply of frozen donor eggs, resulting in London Egg Bank being the largest bank in the country with around 5,000 eggs currently available for donation. Indeed, never before in the UK have donor eggs been more plentiful or from a more varied selection of donors.

A revolution in egg donation

‘Only a few years ago most egg donation patients from Britain had to travel overseas to Spain, Ukraine or Cyprus for their donor eggs,’ explains the London Egg Bank’s medical director Professor Nick Macklon. ‘There, donors were more numerous and the supply of eggs more abundant. But all that changed with vitrification and the technology to freeze and thaw eggs without damage.’ So the London Egg Bank, with a new generation of UK-based donors, is now the largest egg bank in the country, and able to meet the treatment demands of all its patients unable to produce their own eggs.

No longer is overseas treatment necessary, no longer is there a need for long waitinglists or transfers in a ‘fresh’ treatment cycle. The bank of frozen donor eggs can be consulted in an online catalogue and personal preferences for ethnicity or background matched.

Such a wide range of donors is reassuring to many infertile patients who need donor eggs, says the London Egg Bank’s director of nursing Mimi Arian Schad. ‘Egg donation is a big step,’ explains Mimi, ‘and can’t be undertaken lightly. Most egg donation patients have tried IVF before and are now at a stage in life when their ovaries are simply unable to produce the good quality eggs necessary for natural conception. We can remove many of the problems which egg donation patients used to worry about – long waiting lists, traveling abroad, selecting a suitable donor. And these patients are also gratified to know that all our donors are UK citizens and meet the donor requirements of the HFEA. That means a thorough screening procedure, and security for patients, who may not receive that same assurance from a foreign clinic.’

The regulatory requirements of the HFEA in Britain ensure that all treatments are carried out according to a nationally governed and evidence-based code of practice.

Figures show that egg donation is now the most popular fertility treatment in Europe, with the latest figures showing higher live birth rates than those recorded for routine IVF and ICSI, where a woman has used her own eggs. The explanation is simply that donor eggs usually come from healthy young donors without fertility problems and before any age-related decline in their own natural fertility. This is reflected at London Egg Bank, where donors have an average age of 24.

The latest European figures show that almost two-thirds of egg donation patient recipients are 40 years or older. In these women, ovarian function is often no longer what it was several years ago. But there is some good news for them, for what studies have shown beyond doubt – as in all forms of IVF treatment – is that success for the recipient patient depends more on the age of her donor’s eggs than on her own chronological age. For example, the rate of successful pregnancy for a 43-yearold woman is around 50-70% with donor eggs, but only around 5% with her own eggs. Coupled with various studies which acknowledge that frozen eggs perform just as well as fresh eggs in terms of producing a clinical pregnancy, a woman’s chances at starting a family using assisted reproduction are more hopeful than ever before.

The rise in social egg freezing

Another aspect of egg freezing which has gained traction in recent years is that of ‘social’ egg freezing, where women freeze their eggs in order to have a fertility backup plan if they find themselves struggling to get pregnant in future. ‘There is a huge increase in women choosing to freeze their eggs in order to try for a child at a later date – whether it be due to career commitments, financial reasons or finding a suitable partner. By freezing their eggs, our patients feel that they have a wider range of options when it comes to family planning.’ says Professor Macklon.

Marta Wolska, LEB Operations Manager adds, ‘Social egg freezing is becoming increasingly common, with some companies such as Google, Apple and Facebook even offering it to employees so they can have greater control of their fertility options. This is due in part to the encouraging success rates seen regarding clinical pregnancy from frozen eggs, and underlines how far we have come from those initial pioneering fertility treatments of years gone by when routine egg freezing was still just an idea.’

What the future holds

Reproductive medicine in the UK has come a long way since its early years. We are at a point in time where patients no longer need to travel abroad to find a suitable egg donor and where egg freezing and vitrification processes are more successful than ever before in helping to produce a clinical pregnancy.

London Women’s Clinic predicts that more women will embrace social egg freezing as a back-up fertility option, while advances in the vitrification process can ensure continuous rising success rates for IVF patients. As the largest egg bank in the country and the most successful IVF clinic in relation to pregnancy rates per embryo transfer, the London Women’s Clinic and London Egg Bank are at the vanguard of assisted reproduction. The sheer volume of egg donations and vitrification seen by the team ensures an ever-increasing expertise that cannot be matched by smaller clinics, which may only occasionally perform more technical procedures.

Its ‘freeze and share’ programme – where donors can donate half of their eggs from a cycle in exchange for discounted IVF, allows women across the financial spectrum to access fertility treatment at a time in their life which suits them, and which can offer the best possible chances of starting a family.

Much has been achieved, even in the past decade just with the introduction of vitrification alone. The next decade looks set to be just as innovative, if not more.

Professor Nick Macklon Medical Director of London Women’s Clinic Professor Macklon is a world-renowned expert in reproductive medicine. He has held professorships at the University Utrecht in the Netherlands, the University of Southampton and the University of Copenhagen, where he continues to hold an Honorary Chair. He has published over 200 scientific articles, edited several books and is an Editor of Reproductive Biomedicine Online.

A history of 113-115 Harley Street

London Women’s Clinic’s Harley Street Headquarters have long been associated with medicine – in fact there has been a doctor in residence at 113 Harley Street since 1835, when the area was first becoming associated with medicine. Both buildings were built in the 1770s by the same architecture firm behind London’s iconic Somerset House.

The address has been the residence of various doctors and surgeons including Edward Green (a naval surgeon during the Napoleonic wars) and Reginald Vick who ran a field hospital in Flanders during World War One. A dental surgeon named George Northcroft lived and worked at 115 for more than 40 years from 1896, while number 113 was simultaneously occupied by James Calvert, the Warden of Bart’s Medical College.

Political residents of number 115 include Scottish MP David Scott in the late 1700s, who was also a director of the East India Company. Buckinghamshire MP Christopher Tower made 115 his home between 1845 and 1847.

A somewhat more scandalous association was that of barrister Sir William Grove (resident at 115 between 1864 and 1896). Grove famously defended William Palmer, ‘the Rugeley Poisoner’, who was described by Charles Dickens as ‘the greatest villain that ever stood in the Old Bailey dock’.

Since 1984, numbers 113 and 115 have been associated with reproductive medicine – first with Bourn-Hallam Medical Centre and then as the London Women’s Clinic. The site has been the home to many groundbreaking developments within assisted conception, including the world’s first baby carried as an embryo in two different wombs – a concept called shared motherhood.

Above: LWC Founders in 1995 (from left to right) Professor Sir Robert Edwards, Professor Howard Jacobs, Professor Sian Ling Tan and Professor Stuart Campbell