6 minute read

Golf - A Stroke of Luck

Golf

A stroke of luck

For Tiger Woods, the final round of a tournament has to be played in a red shirt, described by his mother Kultida as his power colour.

Dermot Gilleece relates the notorious superstitions of many of our top golfers

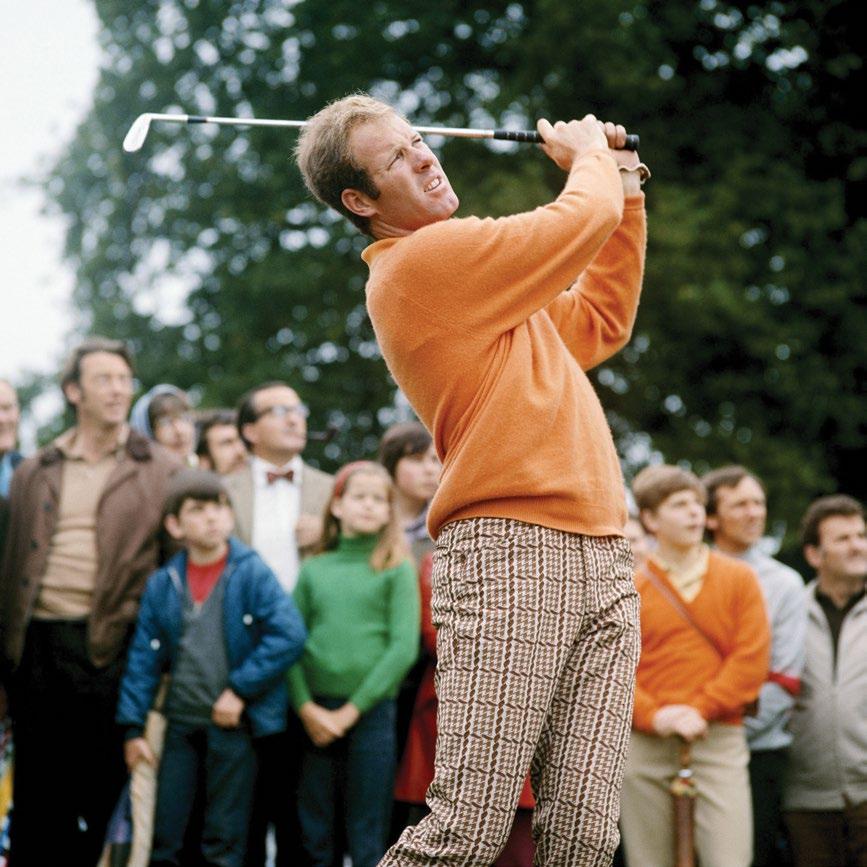

For Tiger Woods, the final round of a tournament had to be played in a red shirt, described by his mother Kultida as his power colour. For Seve Ballesteros, it was a navy-blue sweater and slacks, along with a number four golf-ball as a protection against three-putting. Tom Weiskopf and Jack Nicklaus liked to play with three pennies [cents] in their pocket, while Weiskopf always used a broken tee on a par three.

The fact is that tournament golfers as a group are notoriously superstitious, even though Len Zaichkowsky, an American professor of sports psychology, believes it can have a damaging effect on performance. As he puts it: ‘You are relinquishing belief in your own abilities to some ‘unknown power’ or luck.’

According to Chambers dictionary, superstition is ‘any belief or attitude based on ignorance, that is inconsistent with the known laws of science or with what is generally considered in particular society as true and rational.’ In that context, how does one categorise the beliefs of Gary Player who claimed that God had ordained he would win the modern Grand Slam of the US Open, British Open, US Masters and PGA Championship? The great deed was actually achieved at the US Open at Bellerive, St Louis, in 1965, after a play-off with Kel Nagle. Before the championship got under way, however, Player claimed that his name appeared, clear as daylight, in gold letters at the top of the leaderboard. And to what should we attribute this - superstition or to devout religious belief ?

Professor Zaichkowsky claims that such beliefs serve no useful purpose, even though they might have been adopted with the intention of reducing anxiety. ‘Superstitions have always been prominent among sports people,’ he says, ‘but the idea that a particular object or behaviour brings luck and causes you to play well, is a non-scientific attribution to success or failure.’

All of which is very plausible. But perhaps the good professor will riddle me this: for 71 holes of the 1970 British Open Championship, Doug Sanders stuck with his long-established practice of not using a white tee. On the fateful 72nd hole, however, he made the curious decision to place a white tee in the ground. And the rest, as they say, is history: Sanders missed a two-and-a-foot putt for the title and went on to lose an 18-hole play-off to Nicklaus.

Britain’s Laura Davies has a distinct preference for white tees. Indeed, she has been known, en route to a tournament venue, to drive back to her hotel so as to replenish her supply.

to his status as a golf pundit, put war-paint on his face before going into golf events during his college days at Stanford University. Later on tour, Begay thought it prudent to discard the paint though he continued to say the prayer associated with the ancient practice.

I remember our own Padraig Harrington regretting a score of 67 in a pre-tournament pro-am, on the grounds that it was difficult enough to shoot four good tournament rounds without ‘wasting’ one beforehand. When I suggested, however, that play in the pro-am was of a totally relaxed nature involving relatively easy pin-placements, he began to have second thoughts on the matter.

Still, players continue to pursue that elusive edge, often against natural logic. Like Rory McIlroy sacking his long-time caddie, JP Fitzgerald, after the British Open last July, simply because he felt it might bring about a change in his competitive fortunes. Strategically, there was no reason why it should, but he decided to try it just the same.

Sports psychologists are often confronted with such illogical convictions when attempting to help champion players. And one who handled these challenges better than most, was a diminutive Belgian named Jos Vanstiphout who, sadly, is no longer with us.

I remember a fascinating meeting with him in Chicago in June 2003 on a train to the US Open at Olympia Fields. After exchanging a few pleasantries, Jos was happy to talk about his colourful career which included a spell in a pop band. Now, he proudly described himself as a mental coach who included among his clients, Ernie Els and Retief Goosen, the leading South Africans of that time.

‘I’ve no diploma,’ admitted the amiable Belgian with a ready smile. Which made me all the more curious as to how he could have guided Goosen to victory in a play-off for the US Open at Southern Hills in 2001 and assisted Els to a remarkable British Open triumph, again in a play-off, at Muirfield a year later.

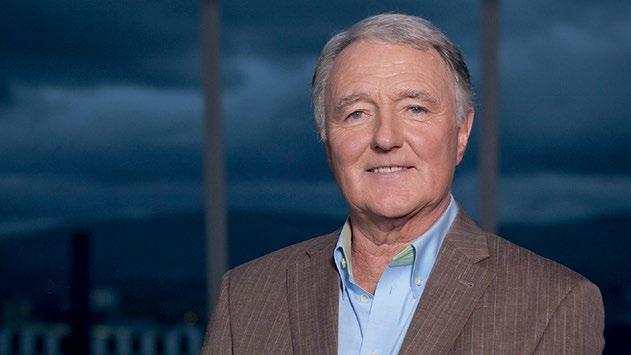

For Seve Ballesteros, it was a navy-blue sweater and slacks, along with a number four golf-ball as a protection against three-putting.

company in November 2002, shortly after the South African had retained the European Order of Merit title. Els remained a client, however, along with Thomas Bjorn and Justin Rose. Indeed, there never seemed to be a shortage of high-profile players ready to hang on his every word.

Els, who had his own superstitions, was probably afraid to do otherwise after the experience of Muirfield. In a tradition reminiscent of San Francisco Giants baseball legend, Orlando Cepeda, he had a habit of discarding golf balls that had delivered birdies, in the belief the “good score” had been used up. Apparently, Cepeda used to throw away a bat once he got a hit with it.

However, Muirfield 2002 was especially interesting. The South African’s ultimate success there was based on an extraordinarily simple device by Vantisphout.

Recalling the event with a wry smile, the self-styled mental coach talked of his client’s down at heel demeanor after squandering the chance of victory in the scheduled 72 holes.

Tom Weiskopf always used a broken tee on a par three.

Vantisphout said nothing. He simply went off and got the South African a sandwich which he handed to him. While thoughtlessly munching the food, Els’s mood suddenly changed. Then, re-focused on his grand objective, he proceeded to beat Thomas Levet, Stuart Appleby and Steve Elkington for the title.

Of course, Woods, the defending champion, was the main focus of attention at Olympia Fields, though the title would go eventually to the little fancied Jim Furyk. In the event, Vantisphout was all ears when El Tigre came in for interview and claimed: ‘Every player I’ve played with [in the US Open] has made a mistake because it is such a pressure-packed environment.’

And the thought occurred as to the extent the great champion was reliant on superstition. From the time he burst onto America’s PGA Tour in August 1996, Woods became a familiar sight on Sundays for the wearing of red. It soon became known as his ‘victory red’ as titles piled up remorselessly on his CV, most notably the Majors, where he was attempting to surpass the record of 18 set by Nicklaus.

‘I’ve worn red on the last day of big events, basically since my college days, or junior golf days,’ he said in a 2013 press conference. ‘I just stuck with it out of superstition, and it worked. I just happened to choose a school that actually was red, and we wore red on our final day of events. So it worked out.’

Ten years earlier, Vantisphout told me: ‘I’ve talked with Tiger; I’ve seen him angry and I’ve seen him frustrated. But the only other sportsman I’ve seen with comparable strength to handle these emotions is the great racing driver, Michael Schumacher. In this regard, Tiger has been greatly influenced by the eastern mysticism of his [Thai] mother.’